Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

15. How Corporations Issue

Securities

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

RELATED WEBSITES

Useful sources of aggregate data on corporate

financing for U.S. corporations include:

www

.census.gov/csd/qfr

(balance sheets and

income statements)

www

.federalreserve.gov/releases

(sources

and uses of funds data)

Material on the changing capital structure of

corporations is provided on:

http:

//fisher.osu.edu/fin

/resources_

educatio

n/credit

Sites on corporate governance and shareholder

rights include:

www

.corpgov.net

www

.corpmon.com

www

.thecorporatelibrary.com

For information on venture capital see:

www

.ipo.com

www

.nvca.org

www.redherring.com

www.tfibcm.com

www.thedeal.com

www.ventureeconomics.com

www.v1.com

www

.vnpartners.com/primer

(a useful

primer on venture capital)

The following sites give information on recent

IPOs:

www

.hoovers.com/ipo

www

.ipo.com

www

.ipodata.com

www

.redherring.com/ipo

www

.thedeal.com

www.edgar-online.com

/ipoexpress

Nasdaq provides a useful explanation of how to

go public together with some data on new

listings:

www

.nasdaq.com/about/going public.stm

Jay Ritter’s home page is a mine of information

on the behavior of IPOs:

http:

//bear.cba.ufl.edu/ritter

Underwriter league tables are published on:

www

.tfibcm.com

This huge SEC database contains prospectuses

and registration statements:

www

.FreeEDGAR.com

PART FOUR

RELATED

WEBSITES

_

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

432

THE DIVIDEND

CONTROVERSY

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

IN THIS CHAPTER we explain how companies set their dividend payments and we discuss the contro-

versial question of how dividend policy affects the market value of the firm.

The first step toward understanding dividend policy is to recognize that the phrase means differ-

ent things to different people. Therefore we must start by defining what we mean by it.

A firm’s decisions about dividends are often mixed up with other financing and investment deci-

sions. Some firms pay low dividends because management is optimistic about the firm’s future and

wishes to retain earnings for expansion. In this case the dividend is a by-product of the firm’s capital

budgeting decision. Suppose, however, that the future opportunities evaporate, that a dividend in-

crease is announced, and that the stock price falls. How do we separate the impact of the dividend

increase from the impact of investors’ disappointment at the lost growth opportunities?

Another firm might finance capital expenditures largely by borrowing. This releases cash for divi-

dends. In this case the firm’s dividend is a by-product of the borrowing decision.

We must isolate dividend policy from other problems of financial management. The precise ques-

tion we should ask is, What is the effect of a change in cash dividends paid, given the firm’s capital

budgeting and borrowing decisions? Of course the cash used to finance a dividend increase has to

come from somewhere. If we fix the firm’s investment outlays and borrowing, there is only one pos-

sible source—an issue of stock. Thus we define dividend policy as the trade-off between retaining

earnings on the one hand and paying out cash and issuing new shares on the other.

This trade-off may seem artificial at first, for we do not observe firms scheduling a stock issue to

offset every dividend payment. But there are many firms that pay dividends and also issue stock from

time to time. They could avoid the stock issues by paying lower dividends. Many other firms restrict

dividends so that they do not have to issue shares. They could issue stock occasionally and increase

the dividend. Both groups of firms are facing the dividend policy trade-off.

Companies can hand back cash to their shareholders either by paying a dividend or by buying back

their stock. So we start the chapter with some basic institutional material on dividends and stock re-

purchases. We then look at how companies decide on dividend payments and we show how both div-

idends and stock repurchases provide information to investors about company prospects. We then

come to the central question, How does dividend policy affect firm value? You will see why we call

this chapter “The Dividend Controversy.”

433

16.1 HOW DIVIDENDS ARE PAID

The dividend is set by the firm’s board of directors. The announcement of the div-

idend states that the payment will be made to all those stockholders who are reg-

istered on a particular record date. Then about two weeks later dividend checks are

mailed to stockholders.

Shares are normally bought and sold with dividend or cum dividend until a few

days before the record date, at which point they trade ex dividend. Investors who

buy with dividend need not worry if their shares are not registered in time. The

dividend must be paid over to them by the seller.

The company is not free to declare whatever dividend it chooses. Some re-

strictions may be imposed by lenders, who are concerned that excessive divi-

dend payments would not leave enough in the kitty to pay the company’s

debts. State law also helps to protect the company’s creditors against excessive

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

dividend payments. For example, companies are not allowed to pay a dividend

out of legal capital, which is generally defined as the par value of outstanding

shares.

1

Dividends Come in Different Forms

Most companies pay a regular cash dividend each quarter,

2

but occasionally this reg-

ular dividend is supplemented by a one-off extra or special dividend.

3

Dividends are not always in the form of cash. Frequently companies also declare

stock dividends. For example, Archer Daniels Midland has paid a yearly stock divi-

dend of 5 percent for over 20 years. That means it sends each shareholder 5 extra

shares for every 100 shares currently owned. You can see that a stock dividend is

very much like a stock split. (For example, Archer Daniels Midland could have

skipped one year’s stock dividend and split each 100 shares into 105.) Both stock

dividends and splits increase the number of shares, but the company’s assets, prof-

its, and total value are unaffected. So both reduce value per share. The distinction

between the two is technical. A stock dividend is shown in the accounts as a trans-

fer from retained earnings to equity capital, whereas a split is shown as a reduction

in the par value of each share.

Many companies have automatic dividend reinvestment plans (DRIPs). Often

the new shares are issued at a 5 percent discount from the market price; the firm

offers this sweetener because it saves the underwriting costs of a regular share is-

sue.

4

Sometimes 10 percent or more of total dividends will be reinvested under

such plans.

Dividend Payers and Nonpayers

Fama and French, who have studied dividend payments in the United States, found

that only about a fifth of public companies pay a dividend.

5

Some of the remainder

paid dividends in the past but then fell on hard times and were forced to conserve

cash. The other non-dividend-payers are mostly growth companies. They include

such household names as Microsoft, Cisco, and Sun Microsystems, as well as many

small, rapidly growing firms that have not yet reached full profitability. Of course,

investors hope that these firms will eventually become profitable and that, when

their rate of new investment slows down, they will be able to pay a dividend.

434 PART V

Dividend Policy and Capital Structure

1

Where there is no par value, legal capital is defined as part or all of the receipts from the issue of shares.

Companies with wasting assets, such as mining companies, are sometimes permitted to pay out legal

capital.

2

In 1999 Disney changed to paying dividends once a year rather than quarterly. Disney has an unusu-

ally large number of investors with only a handful of shares. By making an annual payment, Disney re-

duced the substantial cost of mailing dividend checks to these investors.

3

Special dividends are much less common than they used to be. The reasons are analyzed in H. DeAn-

gelo, L. DeAngelo, and D. Skinner, “Special Dividends and the Evolution of Dividend Signaling,” Jour-

nal of Financial Economies 57 (2000), pp. 309–354.

4

Sometimes companies not only allow shareholders to reinvest dividends but also allow them to buy

additional shares at a discount. In some cases substantial amounts of money have been invested. For

example, AT&T has raised over $400 million a year through DRIPs. For an amusing and true rags-to-

riches story, see M. S. Scholes and M. A. Wolfson, “Decentralized Investment Banking: The Case of

Dividend-Reinvestment and Stock-Purchase Plans,” Journal of Financial Economics 24 (September 1989),

pp. 7–36.

5

E. F. Fama and K. R. French, “Disappearing Dividends: Changing Firm Characteristics or Lower

Propensity to Pay?” Journal of Financial Economics 60 (2001), pp. 3–43.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Fama and French also found that the proportion of dividend payers has de-

clined sharply from a peak of 67 percent in 1978. One reason for this is that a large

number of small growth companies have gone public in the last 20 years. Many of

these newly listed companies were in high-tech industries, had no earnings, and

did not pay dividends. But the influx of newly listed growth companies does not

fully explain the declining popularity of dividends. It seems that even large and

profitable firms are somewhat less likely to pay a dividend than was once the case.

Share Repurchase

When a firm wants to pay out cash to its shareholders, it usually declares a cash

dividend. The alternative is to repurchase its own stock. The reacquired shares

may be kept in the company’s treasury and resold if the company needs money.

There is an important difference in the taxation of dividends and stock repur-

chases. Dividends are taxed as ordinary income, but stockholders who sell shares

back to the firm pay tax only on capital gains realized in the sale. However, the In-

ternal Revenue Service is on the lookout for companies that disguise dividends as

repurchases, and it may decide that regular or proportional repurchases should be

taxed as dividend payments.

There are three main ways to repurchase stock. The most common method is

for the firm to announce that it plans to buy its stock in the open market, just like

any other investor.

6

However, sometimes companies offer to buy back a stated

number of shares at a fixed price, which is typically set at about 20 percent above

the current market level. Shareholders can then choose whether to accept this of-

fer. Finally, repurchase may take place by direct negotiation with a major share-

holder. The most notorious instances are greenmail transactions, in which the tar-

get of a takeover attempt buys off the hostile bidder by repurchasing any shares

that it has acquired. “Greenmail” means that these shares are repurchased by the

target at a price which makes the bidder happy to leave the target alone. This

price does not always make the target’s shareholders happy, as we point out in

Chapter 33.

Stock repurchase plans were big news in October 1987. On Monday, October 19,

stock prices in the United States nose-dived more than 20 percent. The next day the

board of Citicorp approved a plan to repurchase $250 million of the company’s

stock. Citicorp was soon joined by a number of other corporations whose man-

agers were equally concerned about the market crash. Altogether, over a two-day

period these firms announced plans to buy back $6.2 billion of stock. News of these

huge buyback programs helped to stem the slide in stock prices.

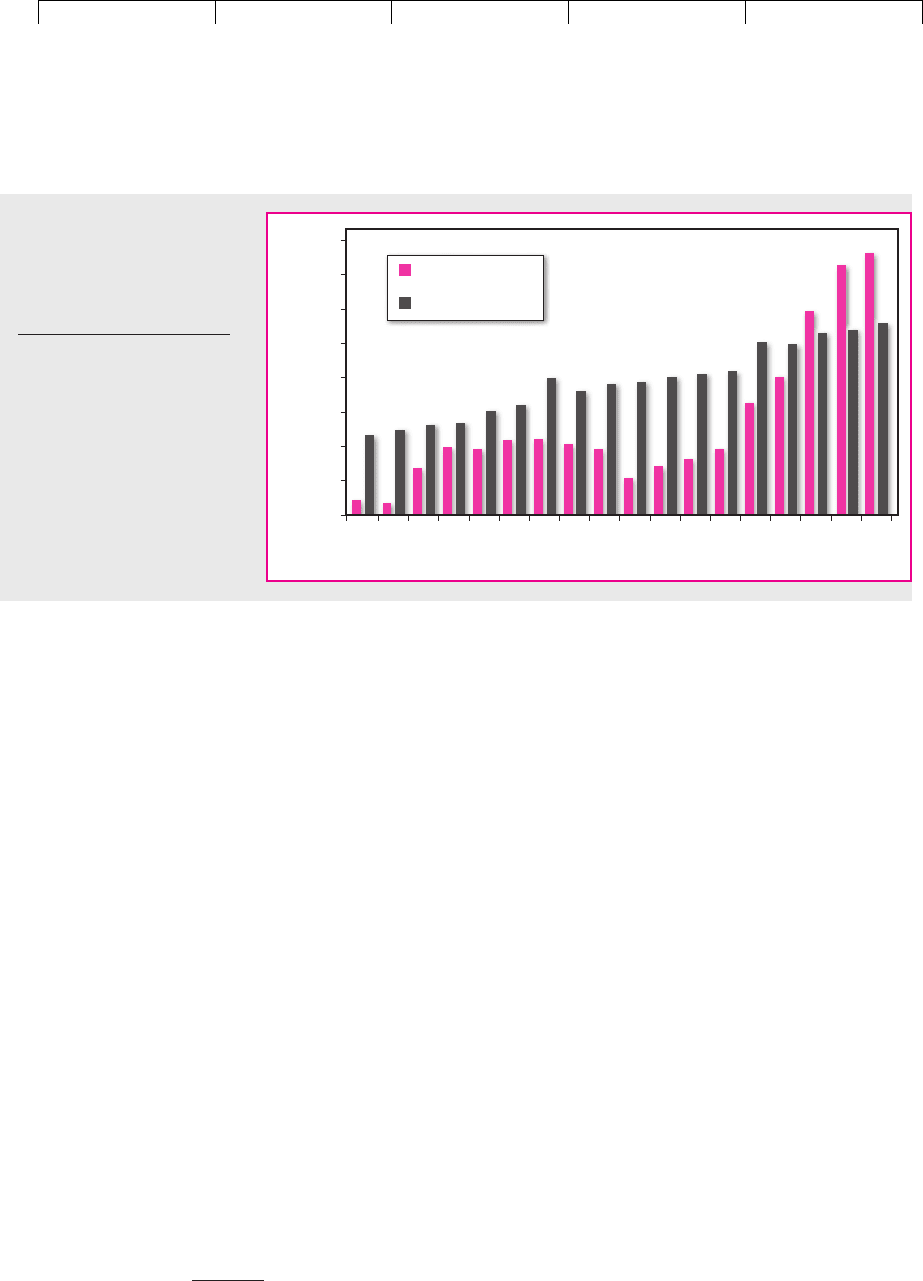

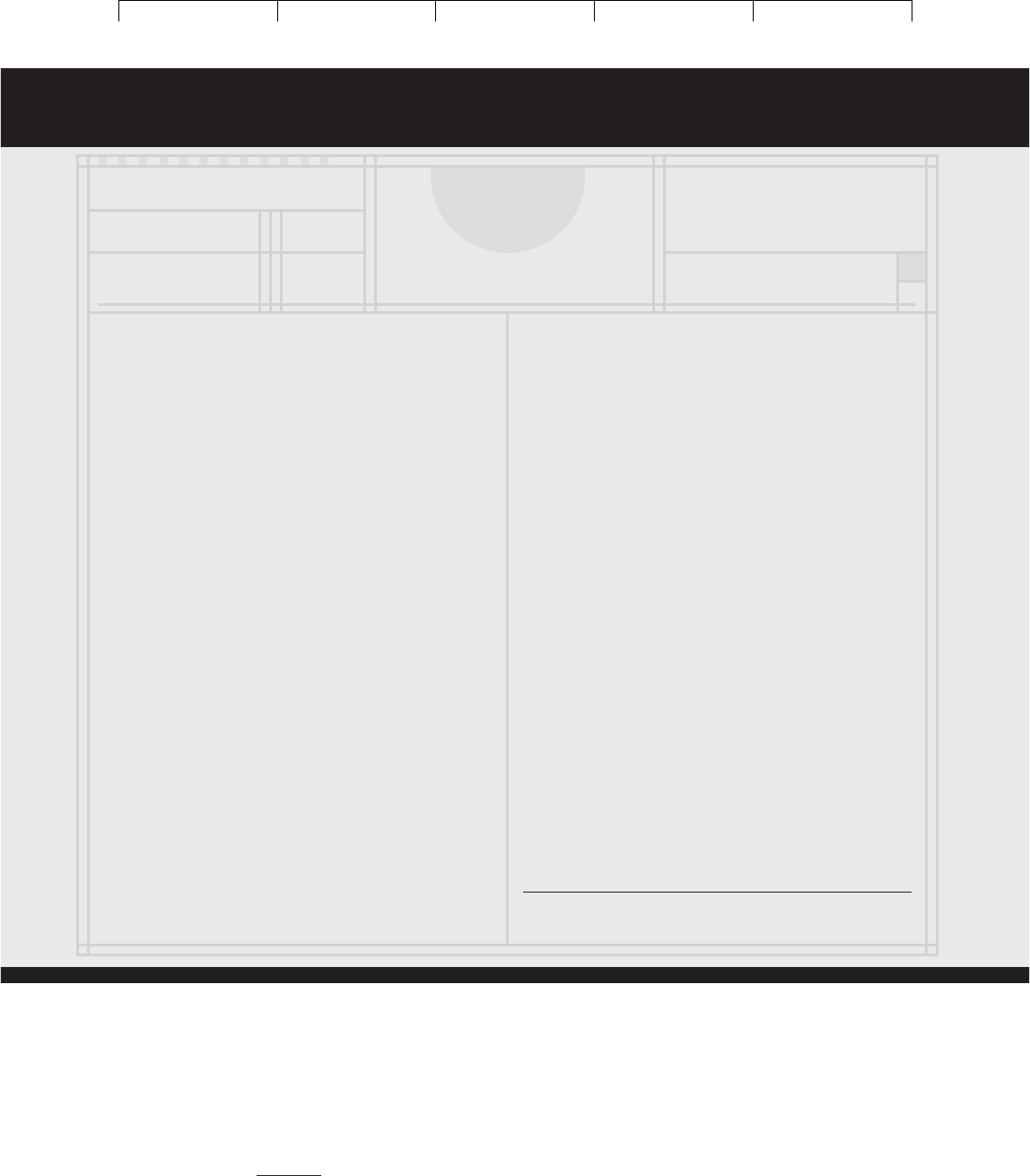

Figure 16.1 shows that since the 1980s stock repurchases have mushroomed and

are now larger in value than dividend payments. As we write this chapter at the

end of October 2001, large new repurchase programs have just been announced in

the last two weeks by IBM ($3.5 billion), McDonald’s ($5 billion), and Citigroup ($5

billion). The biggest and most dramatic repurchases have been in the oil industry,

where cash resources for a long time outran good capital investment opportunities.

Exxon Mobil is in first place, having spent about $27 billion on repurchasing shares

through year-end 2000.

CHAPTER 16

The Dividend Controversy 435

6

An alternative procedure is to employ a Dutch auction. In this case the firm states a series of prices at

which it is prepared to repurchase stock. Shareholders submit offers declaring how many shares they

wish to sell at each price and the company then calculates the lowest price at which it can buy the de-

sired number of shares. This is another example of the uniform-price auction described in Section 15.3.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Repurchases are like bumper dividends; they cause large amounts of cash to

be paid to investors. But they don’t substitute for dividends. Most companies that

repurchase stock are mature, profitable companies that also pay dividends. So

the growth in stock repurchases cannot explain the declining proportion of divi-

dend payers.

Suppose that a company has accumulated large amounts of unwanted cash or

wishes to change its capital structure by replacing equity with debt. It will usually

do so by repurchasing stock rather than by paying out large dividends. For exam-

ple, consider the case of U.S. banks. In 1997 large bank holding companies paid out

just under 40 percent of their earnings as dividends. There were few profitable in-

vestment opportunities for the remaining income, but the banks did not want to

commit themselves in the long run to any larger dividend payments. They there-

fore returned the cash to shareholders not by upping the dividend rate, but by re-

purchasing $16 billion of stock.

7

Given these differences in the way that dividends and repurchases are used, it

is not surprising to find that repurchases are much more volatile than dividends.

Repurchases mushroom during boom times as firms accumulate excess cash and

wither in recessions.

8

In recent years a number of countries, such as Japan and Sweden, have al-

lowed repurchases for the first time. Some countries, however, continue to ban

them entirely, while in many other countries repurchases are taxed as dividends,

often at very high rates. In these countries firms that have amassed large moun-

tains of cash may prefer to invest it on very low rates of return rather than to

hand it back to shareholders, who could reinvest it in other firms that are short

of cash.

436 PART V

Dividend Policy and Capital Structure

1982 1984

1986

1988

1990

Year

1992

1994

1996

1998

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

$ Billions

Repurchases

Dividends

FIGURE 16.1

Stock repurchases and

dividends in the United

States, 1982–1999. (Figures

in $ billions.)

Source: J. B. Carlson, “Why Is

the Dividend Yield So Low?”

Federal Reserve Bank of

Cleveland Economic

Commentary, April 1, 2001.

7

B. Hirtle, “Bank Holding Company Capital Ratios and Shareholder Payouts,” Federal Reserve Bank of

New York: Current Issues in Economics and Finance 4 (September 1998).

8

These differences between dividends and repurchases are described in M. Jagannathan, C. Stephens,

and M. S. Weisbach, “Financial Flexibility and the Choice between Dividends and Stock Repurchases,”

Journal of Financial Economics 57 (2000), pp. 355–384.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Lintner’s Model

In the mid-1950s John Lintner conducted a classic series of interviews with corpo-

rate managers about their dividend policies.

9

His description of how dividends are

determined can be summarized in four “stylized facts”:

10

1. Firms have long-run target dividend payout ratios. Mature companies with

stable earnings generally pay out a high proportion of earnings; growth

companies have low payouts (if they pay any dividends at all).

2. Managers focus more on dividend changes than on absolute levels. Thus,

paying a $2.00 dividend is an important financial decision if last year’s

dividend was $1.00, but no big deal if last year’s dividend was $2.00.

3. Dividend changes follow shifts in long-run, sustainable earnings. Managers

“smooth” dividends. Transitory earnings changes are unlikely to affect

dividend payouts.

4. Managers are reluctant to make dividend changes that might have to be

reversed. They are particularly worried about having to rescind a dividend

increase.

Lintner developed a simple model which is consistent with these facts and ex-

plains dividend payments well. Here it is: Suppose that a firm always stuck to its

target payout ratio. Then the dividend payment in the coming year (DIV

1

) would

equal a constant proportion of earnings per share (EPS

1

):

DIV

1

⫽ target dividend

⫽ target ratio ⫻ EPS

1

The dividend change would equal

DIV

1

⫺ DIV

0

⫽ target change

⫽ target ratio ⫻ EPS

1

⫺ DIV

0

A firm that always stuck to its target payout ratio would have to change its div-

idend whenever earnings changed. But the managers in Lintner’s survey were re-

luctant to do this. They believed that shareholders prefer a steady progression in

dividends. Therefore, even if circumstances appeared to warrant a large increase

in their company’s dividend, they would move only partway toward their target

payment. Their dividend changes therefore seemed to conform to the following

model:

DIV

1

⫺ DIV

0

⫽ adjustment rate ⫻ target change

⫽ adjustment rate ⫻ (target ratio ⫻ EPS

1

⫺ DIV

0

)

The more conservative the company, the more slowly it would move toward its tar-

get and, therefore, the lower would be its adjustment rate.

CHAPTER 16

The Dividend Controversy 437

16.2 HOW DO COMPANIES DECIDE ON DIVIDEND

PAYMENTS?

9

J. Lintner, “Distribution of Incomes of Corporations among Dividends, Retained Earnings, and Taxes,”

American Economic Review 46 (May 1956), pp. 97–113.

10

The stylized facts are given by Terry A. Marsh and Robert C. Merton, “Dividend Behavior for the Ag-

gregate Stock Market,” Journal of Business 60 (January 1987), pp. 1–40. See pp. 5–6. We have paraphrased

and embellished.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Lintner’s simple model suggests that the dividend depends in part on the firm’s

current earnings and in part on the dividend for the previous year, which in turn de-

pends on that year’s earnings and the dividend in the year before. Therefore, if Lint-

ner is correct, we should be able to describe dividends in terms of a weighted aver-

age of current and past earnings.

11

The probability of an increase in the dividend rate

should be greatest when current earnings have increased; it should be somewhat less

when only the earnings from the previous year have increased; and so on. An exten-

sive study by Fama and Babiak confirmed this hypothesis.

12

Their tests of Lintner’s

model suggest that it provides a fairly good explanation of how companies decide

on the dividend rate, but it is not the whole story. We would expect managers to take

future prospects as well as past achievements into account when setting the pay-

ment. As we shall see in the next section, that is indeed the case.

438 PART V

Dividend Policy and Capital Structure

11

This can be demonstrated as follows: Dividends per share in time t are

(1) DIV

t

⫽ aT(EPS

t

) ⫹ (1 ⫺ a)DIV

t⫺1

where a is the adjustment rate and T is the target payout ratio. But the same relationship holds in t ⫺ 1:

(2) DIV

t⫺1

⫽ aT(EPS

t⫺1

) ⫹ (1 ⫺ a)DIV

t⫺2

Substitute for DIV

t⫺1

in (1):

DIV

t

⫽ aT(EPS

t

) ⫹ aT(1 ⫺ a)(EPS

t⫺1

) ⫹ (1 ⫺ a)

2

DIV

t⫺2

We can make similar substitutions for DIV

t⫺2

, DIV

t⫺3

, etc., thereby obtaining

DIV

t

⫽ aT(EPS

t

) ⫹ aT(1 ⫺ a)(EPS

t⫺1

) ⫹ aT(1 ⫺ a)

2

(EPS

t⫺2

) ⫹

...

⫹ aT(1 ⫺ a)

n

(EPS

t⫺n

)

12

E. F. Fama and H. Babiak, “Dividend Policy: An Empirical Analysis,” Journal of the American Statistical

Association 63 (December 1968), pp. 1132–1161.

16.3 THE INFORMATION IN DIVIDENDS AND STOCK

REPURCHASES

In some countries you cannot rely on the information that companies provide. Pas-

sion for secrecy and a tendency to construct multilayered corporate organizations

produce asset and earnings figures that are next to meaningless. Some people say

that, thanks to creative accounting, the situation is little better for some companies

in the United States.

How does an investor in such a world separate marginally profitable firms from

the real money makers? One clue is dividends. Investors can’t read managers’

minds, but they can learn from managers’ actions. They know that a firm which re-

ports good earnings and pays a generous dividend is putting its money where its

mouth is. We can understand, therefore, why investors would value the informa-

tion content of dividends and would refuse to believe a firm’s reported earnings

unless they were backed up by an appropriate dividend policy.

Of course, firms can cheat in the short run by overstating earnings and scraping

up cash to pay a generous dividend. But it is hard to cheat in the long run, for a

firm that is not making enough money will not have enough cash to pay out. If a

firm chooses a high dividend payout without the cash flow to back it up, that firm

will ultimately have to reduce its investment plans or turn to investors for addi-

tional debt or equity financing. All of these consequences are costly. Therefore,

most managers don’t increase dividends until they are confident that sufficient

cash will flow in to pay them.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

There is some evidence that managers do look to the future when they set the div-

idend payment. For example, Benartzi, Michaely, and Thaler found that dividend in-

creases generally followed a couple of years of unusual earnings growth.

13

Although

this rapid growth did not persist beyond the year in which the dividend was

changed, for the most part the higher level of earnings was maintained and declines

in earnings were relatively uncommon. More striking evidence that dividends are set

with an eye to the future is provided by Healy and Palepu, who focus on companies

that pay a dividend for the first time.

14

On average earnings jumped 43 percent in

the year that the dividend was paid. If managers thought that this was a temporary

windfall, they might have been cautious about committing themselves to paying out

cash. But it looks as if they had good reason to be confident about prospects, for over

the next four years earnings grew on average by a further 164 percent.

If dividends provide some reassurance that the new level of earnings is likely to

be sustained, it is no surprise to find that announcements of dividend cuts are usu-

ally taken by investors as bad news (stock price falls) and that dividend increases

are good news (stock price rises). For example, in the case of the dividend initia-

tions studied by Healy and Palepu, the announcement of the dividend resulted in

an abnormal rise of 4 percent in the stock price.

15

Notice that investors do not get excited about the level of a company’s dividend;

they worry about the change, which they view as an important indicator of the sus-

tainability of earnings. In Finance in the News we illustrate how an unexpected

change in dividends can cause the stock price to bounce back and forth as investors

struggle to interpret the significance of the change.

It seems that in some other countries investors are less preoccupied with divi-

dend changes. For example, in Japan there is a much closer relationship between

corporations and major stockholders, and therefore information may be more eas-

ily shared with investors. Consequently, Japanese corporations are more prone to

cut their dividends when there is a drop in earnings, but investors do not mark the

stocks down as sharply as in the United States.

16

The Information Content of Share Repurchase

Share repurchases, like dividends, are a way to hand cash back to shareholders. But

unlike dividends, share repurchases are frequently a one-off event. So a company that

announces a repurchase program is not making a long-term commitment to earn and

distribute more cash. The information in the announcement of a share repurchase pro-

gram is therefore likely to be different from the information in a dividend payment.

Companies repurchase shares when they have accumulated more cash than

they can invest profitably or when they wish to increase their debt levels. Neither

CHAPTER 16

The Dividend Controversy 439

13

See L. Benartzi, R. Michaely, and R. H. Thaler, “Do Changes in Dividends Signal the Future or the

Past,” Journal of Finance 52 (July 1997), pp. 1007–1034. Similar results are reported in H. DeAngelo, L.

DeAngelo, and D. Skinner, “Reversal of Fortune: Dividend Signaling and the Disappearance of Sus-

tained Earnings Growth,” Journal of Financial Economics 40 (1996), pp. 341–372.

14

See P. Healy and K. Palepu, “Earnings Information Conveyed by Dividend Initiations and Omis-

sions,” Journal of Financial Economics 21 (1988), pp. 149–175.

15

Healy and Palepu also looked at companies that stopped paying a dividend. In this case the stock price

on average declined by an abnormal 9.5 percent on the announcement and earnings fell over the next

four quarters.

16

The dividend policies of Japanese keiretsus are analyzed in K. L. Dewenter and V. A. Warther, “Divi-

dends, Asymmetric Information, and Agency Conflicts: Evidence from a Comparison of the Dividend

Policies of Japanese and U.S. Firms,” Journal of Finance 53 (June 1998), pp. 879–904.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

V. Dividend Policy and

Capital Structure

16. The Dividend

Controversy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

On May 9, 1994, FPL Group, the parent company

of Florida Power & Light Company, announced a 32

percent reduction in its quarterly dividend payout,

from 62 cents per share to 42 cents. In its an-

nouncement, FPL did its best to spell out to in-

vestors why it had taken such an unusual step. It

stressed that it had studied the situation carefully

and that, given the prospect of increased competi-

tion in the electric utility industry, the company’s

high dividend payout ratio (which had averaged 90

percent in the past 4 years) was no longer in the

shareholders’ best interests. The new policy re-

sulted in a payout of about 60 percent of the pre-

vious year’s earnings. Management also an-

nounced that, starting in 1995, the dividend payout

would be reviewed in February instead of May to

reinforce the linkage between dividends and an-

nual earnings. In doing so, the company wanted to

minimize unintended “signaling effects” from any

future changes in dividends.

At the same time that it announced this change

in dividend policy, FPL Group’s board authorized

the repurchase of up to 10 million shares of com-

mon stock over the next 3 years. In adopting this

strategy, the company noted that changes in the

U.S. tax code since 1990 had made capital gains

more attractive than dividends to shareholders.

Besides providing a more tax-efficient means

of distributing excess cash to its stockholders,

FPL’s substitution of stock repurchases for divi-

dends was also designed to increase the com-

pany’s financial flexibility in preparation for a new

era of heightened competition among utilities. Al-

though much of the cash savings from the divi-

dend cut would be returned to shareholders in the

form of stock repurchases, the rest would be used

to retire debt and so reduce the company’s lever-

age ratio. This deleveraging was intended to pre-

pare the company for the likely increase in busi-

ness risk and to provide some slack that would

allow the company to take advantage of future

business opportunities.

All this sounded logical, but investors’ first reac-

tion was dismay. On the day of the announcement,

the stock price fell nearly 14 percent. But, as analy-

sis digested the news and considered the reasons

for the reduction, they concluded that the action

was not a signal of financial distress but a well-

considered strategic decision. This view spread

throughout the financial community, and FPL’s

stock price began to recover. By the middle of the

following month at least 15 major brokerage

houses had placed FPL’s common stock on their

“buy” lists and the price had largely recovered

from its earlier fall.

Source: Modified from D. Soter, E. Brigham, and P. Evanson, “The

Dividend Cut ‘Heard ‘Round the World’: The Case of FPL,” Journal

of Applied Corporate Finance 9 (Spring 1996), pp. 4–15.

circumstance is good news in itself, but shareholders are frequently relieved to see

companies paying out the excess cash rather than frittering it away on unprofitable

investments. Shareholders also know that firms with large quantities of debt to

service are less likely to squander cash. A study by Comment and Jarrell, who

looked at the announcements of open-market repurchase programs, found that on

average they resulted in an abnormal price rise of 2 percent.

17

440

FINANCE IN THE NEWS

THE DIVIDEND CUT HEARD ’ROUND THE WORLD

17

See R. Comment and G. Jarrell, “The Relative Signalling Power of Dutch-Auction and Fixed Price Self-

Tender Offers and Open-Market Share Repurchases,” Journal of Finance 46 (September 1991),

pp. 1243–1271. There is also evidence of continuing superior performance during the years following a

repurchase announcement. See D. Ikenberry, J. Lakonishok, and T. Vermaelen, “Market Underreaction

to Open Market Share Repurchases,” Journal of Financial Economics 39 (1995), pp. 181–208.