Boardman J., Hammond N.G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ECONOMIC TENSIONS 43

5

lest the Phocaeans should establish a market there, and exclude their

merchants from the commerce of those seas'. All states tapped

commercial gains through market and harbour dues, which were a

major source of actual cash revenues for public treasuries. The polis

provided at least partial compensation for this exploitation, if not always

intentionally, by standardization of weights and measures, issue of

coinage, better water supplies and harbour works; Corinth even built

a causeway across its isthmus to facilitate the passage of ships.

The development of the Hellenic states down to 500, however,

provides no place for a powerful urban bourgeoisie. Assemblies and

upper classes alike were rurally based, and could even look askance at

the rise of commercial and industrial sectors in cities and ports; an

enduring ideal of the,

polis was

self-sufficiency

(autarkeia).

These elements,

moreover, were a small part of the population of any state, with almost

no formal organization; and in any case the political machinery of the

polis was too limited to go far beyond guaranteeing local order and

justice in its markets. The effort of the Pisistratids to gain control of

the Hellespont was an unusual foreign step which may not have had

the commercial motive often assigned to it.

If we look at the economic growth of Greece as a whole over the period

800—500, it is impossible to define that expansion in statistical terms;

the numbers of stone temples built in the era and the volume of

surviving statues, vases and other objects may subjectively support the

suggestion that economic quickening began to be visible in the eighth

century, grew in the seventh century, but attained major proportions

only in the sixth century. What is certain is that by ever more skilful

exploitation of native resources and a geographical position between

the developed Near East and the barbarian farther shores of the

Mediterranean the population of Greece covered its needs, expanded

its numbers to some degree and even produced a modest surplus. On

that surplus, local and international, rested the development of such

great shrines as Olympia and Delphi and also the architectural and

sculptural embellishment of the

poleis;

so too philosophers, poets and

others could be given the leisure necessary for their magnificent

achievements.

This economic activity, it should be recalled, was essentially carried

on by free

men.

In

a

few areas farmers sank into bondage, slavery became

more prevalent in the workshops of Greece, but even peasants remained

citizens of the

polis.

Econbmic progress led to very different results in

the ancient Near East and in early modern Europe; the roots of the

difference lie in the tiny scale of Greek political organization and its

inheritance of a sense of general communal unity. By 500 the more

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

436 45

a

- ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS

advanced Hellenic centres

had

developed

an

interwoven structure,

differentiated

in

economic elements but focused

on 'a

set place

in

the

middle of their city, where men come together to cheat each other and

forswear themselves'.

The

last clause

in

Cyrus' observation also

deserves stress;

by

500

B.C.

important parts

of

the Greek world had

developed

a

conscious economic drive. Even though

a

work-ethic

of

modern type never became master and ' profit' was

a

simply felt concept,

the spirit of Greek market places was summed up on a black-figure vase

showing the sale

of

oil (Vatican 413) and inscribed, 'Oh father Zeus

may

I

get rich'.

16

VI.

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

From the Dark Ages the Greeks inherited an intricate social pattern and

code

of

behaviour in sexual and other relationships. Above the family

(oikos),

which included the physical possessions necessary for survival,

there were territorial units ranging from village

to

ethnos,

religious

groupings about local shrines, brotherhoods, ties between aristocrats

and their followers, and many others.

Any single Greek, male or female, adult or child, was thus linked

to

his fellows by many bonds of different sorts, which he usually accepted

both

in

their limitations and in their support of his existence. We lack

reliable ancient evidence

to

explore

in

depth these social patterns,

important though they were;

it is

equally impossible

to

speak firmly

about alterations unless we import recent anthropological and socio-

logical theory. Much attention, for instance, has been given in modern

studies

to

the

genos

or

clan

as a

focus

for

aristocratic activity, yet the

genos

does not appear in Homer and its presence even in Attica shrinks

primarily

to

priestly families

if

the evidence

is

closely inspected.

17

In

general

one may

surmise that

the

rise

of

the polis slowly gave

an

overarching unity

to its

population

and

that territorial units gained

strength

at

the expense of other groupings; but even

a

statement such

as this applies primarily to Athens.

More

can be

said about the evolution

of

classes during the great

changes of Greek life, which acted as

a

centrifuge to spin apart and

to

differentiate elements in the population. On the top of the spectrum was

the small group

of

leading families which became

an

aristocracy,

i.e.

a class stamped by shared values and way of life differing markedly from

other elements

in

society and accepted

by

those others

as

'the best'

[aristot).

Archaeologically

a

distinction

in

grave goods begins

to be

perceptible

by the

ninth century;

in

Archaic poetry

an

aristocratic

outlook

is

clearly manifest from Archilochus onwards. The eighth

16

H 18, fig. 212. " C J.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENTS 437

century, thus, appears

to

have been the critical stage in the conscious

evolution

of

Greek aristocracy.

In any one

polis

truly aristocratic families were numbered only in the

range of the one hundred noble 'houses' of Locri Epizephyrii (Polyb.

XII.

516). Below

the

major landowners proud

of

their lineage stood

masses

of

middling farmers, who reinforced the ranks

of

the infantry

phalanx as

it

became the dominant tactical formation on the battlefields

in the seventh century. This level could be praised by the poets, as

in

Phocylides' assertion (fr. 12), 'Midmost

in

a.polis

would

I

be';

it

did

not, however, form

a

distinct class,

and

even

the

concept

of an

independent political force termed ' the hoplite class' can be misleading.

Aristotle, true, refers

to

constitutions based

on

membership

in the

infantry phalanx as against aristocracies on horseback (esp. Pol. 1288a,

1297b, 1321a);

but his

views

of

early Greek history

are

seriously

distorted by the political conditions of the fourth century. Aristocrats

stood beside the middling farmers in the phalanx, and politically as well

as economically there is no evidence that kakoi worked as a group rather

than for individual advantage. Socially, in particular, successful men of

this stamp sought to acquire the aristocratic pattern of

life,

an effort well

attested

in

the poetry

of

Theognis. The poorest landowners and

the

landless

thetes

were, on the other hand, quite distinct as the lowest rung

of the agricultural world.

When cities came into existence, they supported industrial

and

merchant groups. Historians especially

in the

earlier years

of the

twentieth century tended to magnify the role of these elements as if they

had formed

a

bourgeoisie; yet they cannot be completely dismissed

in

their invigorating influence

on

Greek life. The disdain

for

physical

labour and economic gain which stamps the work of Plato and Aristotle

(e.g. Pol. 1277b) was

a

philosophical construct never fully applicable

to Greek economic life. Even

if

Herodotus (11. 167) makes

the

observation that in his day traders and artisans had little repute except

in Corinth, there

is

adequate information that they had pride

in

their

callings and could attain wealth; two potters

at

Athens dedicated

a

bronze statue

to

Athena.

18

Slavery was a different matter. Greece had known household slavery

in the Dark Ages, and the figure

of

Eumaeus

in

the

Odyssey

as well

as

Hesiod's references attests scattered rural slavery; but in the expansion

of Greek economic life the workshops came

to

need more manpower

of dependent character than could be drawn from the countryside, even

though women were also active to some degree in industry and trade.

The consequence was a growth in industrial slavery. Chios is reported

as the first state thus

to

use slaves acquired from non-Greek sources

178.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

438

45

fl

-

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS

(Theopompus, FGrH 115 F 122); Solon's poetry shows that Athenians

themselves could be sold into slavery in other Greek states, from which

he somehow ransomed them.

Marxist and Christian thinkers agree

in

the vehemence

of

their

denunciations

of

slavery. Without denying the evil effects

of

the

institution it must be observed that down to 500 industrial slavery in

Greece was of very restricted scope.

19

Its appearance suggests first that

the workshops of the more advanced Greek states had a steady enough

demand to warrant the purchase of slaves and also that their owners

had sufficient capital to acquire such forced labour. True rural slavery,

as already noted, remained limited as against the spread of helotry.

Indeed, Greek states had as many variations in bondage, whether for

debt or by purchase, as they did in citizen classifications.

VII.

ARISTOCRATIC LIFE

The most important force in social evolution during our period was

the crystallization of aristocratic standards and a way of life generally

accepted by

a

community

or

even officially enforced by rules and

officials in the Cretan states and in Sparta. As the term aristocracy is

used in the present chapter, its pattern existed only

in

embryo

in

Homeric

arete;

20

and in view of the extensive modern hostility to elites

it should also be noted that Greek aristocratic patterns were essentially

a refinement and clarification of general Hellenic views of life. Hesiod,

who cannot be termed an aristocrat, illustrates aspects of ethical and

social attitudes which were later part and parcel of aristocratic thought.

By the time of Sappho and Alcaeus, in the late seventh century, the

pattern had become conscious and articulated. All poets of the Archaic

period expressed its values and thus helped to spread it as a common

Hellenic heritage; even more important for its transmission were the

frequent intermarriages of aristocrats from different

poleis

and also their

rivalries and meetings at the international athletic festivals of Olympia,

Delphi and elsewhere, the rise of which was in many ways a mark of

aristocratic consolidation. The same verse is attributed both to Solon

(fr. 23) and to Theognis (1253-4): 'Happy he who has dear children,

whole-hooved steeds, hunting hounds and a friend in foreign parts.'

Since there were no hereditary titles in ancient Greece, aristocrats

could identify themselves only on the basis of lineage; but landed wealth

was also an important requirement. Seventh-century archons at Athens

were chosen 'on birth and wealth' (Ath. Pol. 3); when Simonides was

19

The

standard view

may be

found

in G 13, ch. in,

with abundant references;

a

very different

one

in G 30,

which received

a

Marxist critique

in G 23.

20

G 32; G 7; A 63,

302-11.

A

very different view

in G

r,

34.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ARISTOCRATIC LIFE 439

asked who were well-born, his reply ran, 'Those rich from

of

old'

(Stobaeus,

Anthologium

iv. 29). The possession

of

wealth became,

if

anything, more important as Greece developed, for Theognis attacks

those parvenus who might win away his beloved Cyrnus in bitter tones

which suggest some social mobility by the close of the sixth century.

An evident characteristic of

the

developed aristocratic way of life was

its male orientation. Men associated together in the agora, gymnasium

and symposia, to a degree unusual in the aristocratic societies of modern

Europe. Homosexuality was accepted,

on

this level,

by the

sixth

century, when nudity was normal

in

athletic sports. Women perhaps

sank correspondingly in position. Hesiod engages in terse depreciations

of the female sex; Semonides

of

Amorgos went much farther

in

his

vitriolic differentiation of women as such evil types as sows, vixens or

bitches. Yet it is at least interesting that in the fragments of Sappho there

is not one surviving word to reveal deep bitterness on the relation of

the sexes.

If

the most richly appointed graves

of

our period were

normally of women, does that fact attest only the ostentation of their

husbands?

Another ingredient

in

the aristocratic ethos was

its

emphasis

on

military valour and athletics; both eventually attained prominence

at

Sparta, thanks to local conditions, but were significant at Athens and

elsewhere. Aristocrats vied

in

athletic contests, local and panhellenic;

they hunted in peacetime; and above all they showed their magnificence

in owning horses and even chariots, a prime example of what Thorstein

Veblen called 'conspicuous consumption' inasmuch

as

horses were

difficult to maintain in the Greek landscape and of no economic utility.

Still, horses and chariots appear abundantly in archaeological contexts,

both as figurines and

as

subjects

of

vase-paintings; and names com-

pounded with Hippo- were common on the aristocratic level. Unlike

Homeric heroes, however, who tended sheep and drove ploughs

in

peacetime, historic Greek aristocrats

did not

demonstrate physical

prowess by actually labouring on the land; they were

plousioi.

In athletics as

in

the political and social life

of

the polis the bitter

contentiousness or agonistic spirit of the developed aristocratic pattern

is present. After the kings disappeared there was no one power which

could check this factionalism for honour, and also for profit; the history

of Athens

in

the earlier sixth century illustrates how

far

aristocratic

rivalry could divide

a

state. Aristocratic ethics did not emphasize the

telling

of

truth (as

in

contemporary Persia)

or

charity and brotherly

love;

its tone was

far

franker, as

in

the advice

of

Theognis (363—4),

' Speak your enemy fair, but when you have him

in

your power

be

avenged without pretext'. Vicious verbal attacks

on

the ancestry

or

personal life of opponents were standard from Archilochus and Alcaeus

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

44° 45

a

- ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS

on

to

Athenian politicians

of

the fourth century; assassinations

to

avenge outraged honour

or the

exile

of

defeated opponents were

common. Aristocrats did have a moral code, which was in most respects

summed up in Aristotle's ethical treatises; but it was not of a high order.

The statement ' Nothing too much' was its most famous precept from

Hesiod onward.

Outward display of wealth was a requisite for that 'proper greatness

of spirit' which Aristotle (EM. Nic. 1123b) considered an aristocratic

virtue. The upper classes of the tiny

poleis

could not afford the pomp

of Assyrian and Persian monarchs; instead

of

gold and silver vessels

Greek aristocrats had to make do with elaborately painted vases, but

they came

to

the agora distinguished by purple robes

at

Colophon or

by golden cicadas in their hair at Athens. The recently discovered statue

of Phrasikleia shows

an

aristocratic female with earrings, necklace,

bracelet, elaborate hair crowned by

a stephane

and

a

robe elegantly woven

and decorated. In boasting that he ate 'not what is nicely prepared but

demands common things like

the

rabble', Alcman

(fr. 33)

attests

distinction even in diet; elegance in furniture and aristocratic leisure are

shown in the symposia scenes on vases.

In modern eyes this uneconomic ostentation

is

reprehensible,

but

before entirely condemning the Greek aristocratic way of life we must

put into the scales a truly great fruit of the Archaic era. The aristocrats,

that is to say, supported with remarkable openness of mind the cultural

expansion

of

their age, which underlay Classical achievements. Very

generally

the

aristocrats lived

in the

urban centres

of

artistic

and

intellectual fervour; Sappho dismisses some unfortunate girl

as 'a

farm-girl in farm-girl finery. .. even ignorant of

the

way to lift her gown

over

her

ankles'

(fr.

57).

By

their commissions

and

purchases

the

aristocrats supported the swift developments of the

arts;

into intellectual

progress they entered more directly. Thales, the first philosopher and

counsellor of the Ionian Greeks, was of aristocratic lineage as were most

later philosophers. Except for Aesop the writers

in

poetry and prose

were of aristocratic origin. Greek thought in the Archaic era is marked

by its freedom of speculation and invention, by a sense of personal worth

and even individual independence (though the poets lamented human

amechania

or

helplessness before divine power), by

a

lack

of

trammels

imposed either

by

superstition

or

social convention. These qualities

were given more scope both

by

the expansiveness

of

contemporary

social and economic structures and also by the character of the leading

classes.

As the Greek world developed toward 500, its aristocracies very often

lost their political pre-eminence and had to share power in the various

poleis

with other elements, either the whole citizen body as

at

Athens

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ARISTOCRATIC LIFE 441

or the broad group of rural freeholders of phalanx standing as at Sparta.

Their economic strength was thereby attenuated; their leading social

position

and

their influence

on

Greek culture were

not

weakened.

Aristocrats

had

placed their stamp

on

that civilization during

the

centuries in which its fundamental characteristics, already evident in the

Homeric epics and

in

Dipylon pottery, were made conscious, were

elaborated, and were refined. In later centuries Greek culture never lost

this imprint

but

passed

it on via the

Romans

to

modern western

civilization.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER 45b

THE MATERIAL CULTURE

OF

ARCHAIC

GREECE

JOHN BOARDMAN

It would

be

heartening

to

believe that our knowledge

of

the material

conditions

of

life

in

ancient Greece improves

as

attention shifts from

the earlier periods

to

the later.

In

many respects

it

becomes the poorer

and

it is for

the

earliest settlements

and

their comparatively simple

trappings that we have the fullest evidence. Continuous occupation

of

the major sites

has

rendered

it

difficult

to

do

more than sample

the

evidence

for

any given period

and

it is

possible,

for

instance, still

to

be unsure whether even Athens had a city wall in the sixth century B.C.:

evidence

for

it is

allusive only,

in

texts,

and on the

ground there

is

nothing. Criteria other than acreage have

to

be

applied

to

determine

population numbers and in the Archaic period none inspire confidence.

Even relative growth and decline, which might be gauged from the sizes

of cemeteries, must depend upon more complete survival and excavation

that

it

has generally proved possible

to

achieve. While

the

increasing

sophistication of life greatly diversifies the archaeological record

it

has

also meant that the range of possibly relevant evidence has widened

to

include important classes

of

objects which have survived irregularly

(metalwork)

or

not

at

all (parchment, papyri, textiles). True, the figure

arts

of

Greece tell more through detailed depiction

of

life. This

has

meant, for instance, that we learn about eighth-century weapons mainly

from excavated objects, sixth-century ones from pictures

of

them

or

allusions

in

poetry, and

it

is not easy

to

say which period

is

the more

reliably and completely served. The greater diversity

of

artefacts does

at least mean that greater precision is possible

in

definition

of

date and

origin,

and

this proves,

as

other chapters have shown,

a

vital source

of conventional historical information, especially about trade and about

the origins

of

Greeks

far

from home.

Our knowledge

of

the mainland cities

is

poorer than that

of

new

colonial foundations

or

of

the

comparatively recent foundations on the

eastern shores

of

the Aegean.

In

the

older cities

of

Greece where

an

acropolis had been

a

central fortified feature, as

in

Athens, occupation

had long before outgrown it and, as in Athens, we may be left uncertain

whether

the

lower town

was

fortified.

It is

likely that Pisistratus

442

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MATERIAL CULTURE OF ARCHAIC GREECE

443

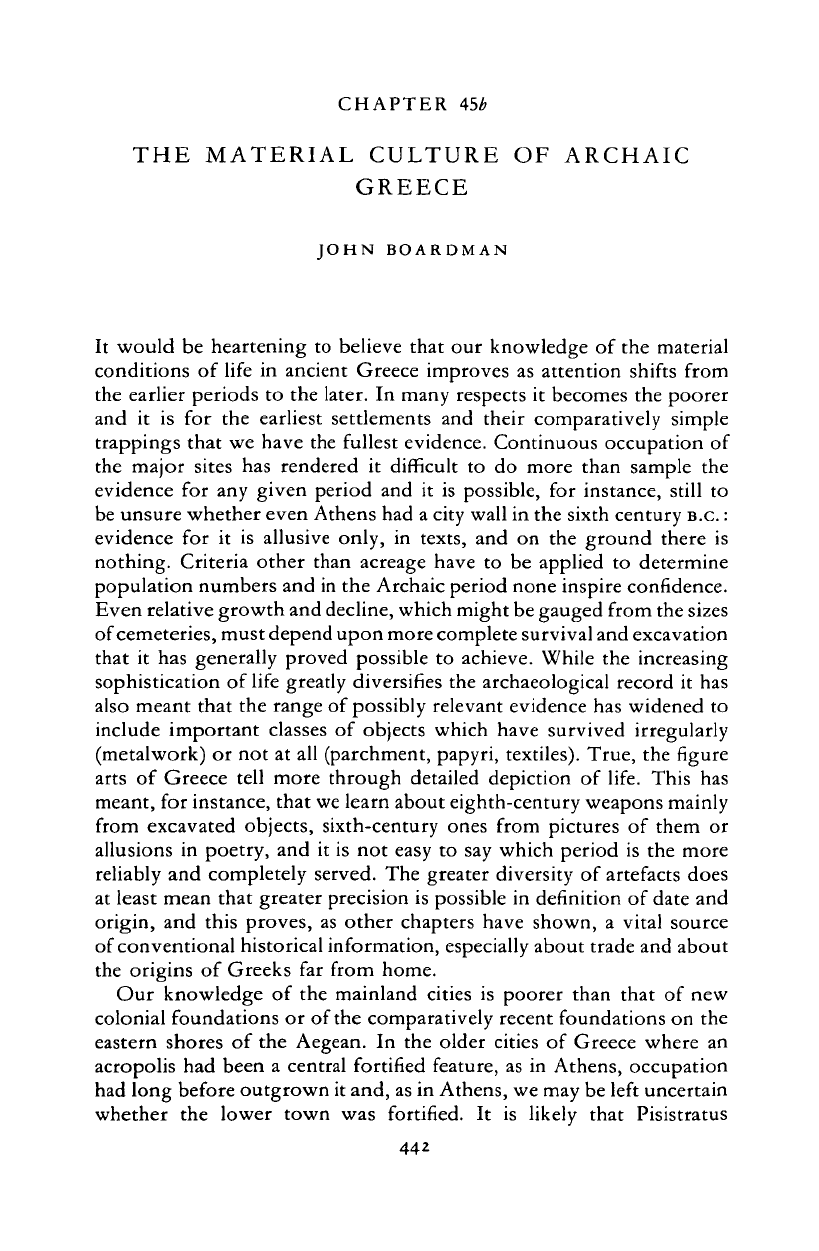

54.

The late seventh-century wall

at

Smyrna, reconstructed

by

R. V.

Nicholls. See also p. 202,

fig.

31. (After D 24,

112,

fig.

34;

D

25, 73,

fig.

20.)

provided some sort of perimeter, though the ease of access by his own

men (returning) and later by Spartans and Persians, suggests that our

difficulties in locating it on the ground reflect its light and impermanent

character.

1

Athens was quick

to

devote

its

acropolis

to

the gods and

to lay out its administrative area round the agora (see below, and Plates

Vol.)

but of

the rest

of

the town

all we

can judge

is

that although

occupation may have been dense in the agora area before

it

was cleared

(by Solon

?)

it could still accommodate minor cemeteries and industry

—

a

potter's yard. Athens seems

to

have remained

a

shapeless, ill-defined

settlement, muddled by its past until lawgivers and a tyrant family take

it

in

hand.

In other cities, like Corinth, Argos, Eretria, the acropolis was more

of

a

fortified refuge

for the

settlement

on the

lower slopes.

The

possibilities

of

defence

for

the lower town were naturally taken more

1

H 79,

6l

4; F 90; F 84.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

444 45^-

THE

MATERIAL CULTURE OF ARCHAIC GREECE

Metres

o

IOO

)).

Sketch plan of the city

of

Samos. (After

D

97, figs. 21, 24.)

seriously.

At

Eretria

it

seems that long walls might have

run

from

acropolis

to

harbour already

in the

seventh century. This has been

thought less likely

at

Corinth but there

is

evidence

for at

least local

fortification

in

the area of the potters' quarter on the lower slopes

of

Acrocorinth.

2

For architectural show and elaboration

of

town plans and fortifica-

tions we have to look elsewhere. Excavation and the accidents of history

have ensured

for

us

a

clear record

of

the great walls

of

Smyrna (fig.

54)

down to its fall in the early sixth century.

3

It cannot have been unique

but

a

site which relied, as Smyrna did, on the isolation of a peninsula

presents different problems from one dependent on an inland acropolis,

like the homeland cities mentioned in the last paragraph or, for instance,

Samos, where the walls embracing the heights, harbour and

a

stretch

of coastline were most probably built under Polycrates (fig. 55). Here

too we find an early example of the sophistication of towers and ditch,

and Herodotus' brief account

of

the Spartan siege suggests that they

were

a

stout obstacle.

In a

town like this

the

whole walled area

(a

triangle with roughly

1 • 5

km sides) was not built up and the wall line

2

Corinth

-

H

79, 64; E 224. Eretria

-

H

79, 61;

D

6,

i3off;

D 14, 89-94.

3

See

CAH

11.z

2

, 798-800, and above, pp. 197,

202-3;

D 73.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008