Boardman J., Hammond N.G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PURSUIT OF POWER BY INDIVIDUALS 345

descent, identified himself with enmity

to

the Dorians and rose

as

champion of the non-Dorian subject peoples of Corinthia. Nothing is

further from the literary tradition. There the Cypselids' claim was that

they were desended through Eetion from a famous clan of Lapiths who

did battle with the Centaurs

in

Thessaly and through Labda from

Heracles who killed some of the Centaurs; and that Eetion's forebear,

Melas of Gonousa, was

a

founding father of Dorian Corinth, having

joined the expedition of Aletes and his Dorians, and so was an original

'Korinthios'. A scene of the troops of Melas and Aletes fraternizing,

in the opinion of Pausanias (v. 18.7-8), was represented on the cedar

'Chest of Cypselus', dedicated at Olympia by Cypselus' successors in

the tyranny. Thus they identified themselves with the ruling aristocracy

of Dorian Corinth from its start, and their choice of themes for the chest,

including Heracles' killing

of

the Centaurs, was

as

aristocratic

as

Pindar's choice of themes for his epinician odes.

37

Tyranny at Megara arose from faction among the oligarchic leaders

{hegemones),

as we have seen in Theognis' verses to Cyrnus. On his way

to power Theagenes won the confidence of the common people ' by

slaughtering the cattle

of

the rich'. Since Aristotle cited this

as an

example of the would-be tyrant misleading the people

{Pol.

1305322-6),

he was indicating not that Theagenes was a lover of the people but that

the people failed to realize his true nature. No doubt Theagenes was

a Dorian aristocrat. The origin of the tyranny at Sicyon is shrouded in

the mists of folk-tale and in fourth-century historical fiction, but two

details have been used to suggest a humble origin for the first tyrant

Orthagoras: that his father Andreas was a cook and that his popularity

with the common people led to his being elected polemarch, magistrate

for war.

If

the facts are true, which is improbable, they do not serve

this purpose; for Andreas was in charge of sacrifices on a mission

to

Delphi and thus was acting as a priest, and

it

is unlikely that anyone

was elected as polemarch from the people by the people in seventh-

century Dorian Sicyon. Rather priesthoods were hereditary

to

noble

houses, and senior magistracies were the preserves of oligarchic clans.

38

As

far

then

as

the evidence goes (and

it is

very sketchy), we may

conclude that tyranny gew out

of

oligarchy when the ranks

of

the

oligarchs split and one faction-leader among the oligarchs used force

to seize power; and that sometimes he enlisted the help of

a

part of the

common people, whom he had duped into trusting him.

37

Hdt. v.

92/3.1;

D.L.

i.

94.1; Paus. 11.

4.4; v.

18.7-8.

For the

cedar chest

see

Stuart Jones

in

JHS

14

(1894)

jo, 80.

38

D.S. vrn. 24;

FGrH IOJ

F 2.

Cleisthenes belonged

to the

tribe which

was not

Dorian,

but

the incorporation

of

that tribe

was

certainly earlier than

the

setting

up of the

tyranny. Priestly

families were

no

doubt included

in it.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

346 4

2

- THE PELOPONNESE

In the passages which we have cited violence and bloodshed were

attributed rather to the period of strife

{stasis)

which preceded tyranny

than to tyranny

itself;

and in the collection of poems which goes under

the name of Theognis the miseries of men were not tortures and killings

at the hand of tyrants but the cycle of betrayal by comrades, banishment

by rivals in power and penury in exile which attended

stasis.

No doubt

bloodshed, banishment and expropriation were weapons in the tyrant's

armoury when he first seized power. Indeed they were an integral part

of the revolution he was bringing about. But they seem

to

have been

used

not

indiscriminately

but

against rival oligarchs, such

as the

Bacchiadae to whom Cypselus was to be'

a

rolling stone'. What the early

poems did stress was not loss of life under a tyranny but loss of liberty,

'slavery'. This was probably correct; for once a tyrant had established

his power, albeit by violence, his aim was not

to

kill but

to

come

to

terms with other aristocratic houses, pacify the state and strengthen

himself against the emigres. Within the Peloponnese the allegations of

brutality

and

massacre which were made

by

later writers, such

as

Herodotus (v. 927;), were directed rather against the last ruler in a series

of tyrants, and no doubt some

of

them were true.

Tyranny came

to

stay for three generations

at

Corinth

{c.

657-583

B.C.) and for

a

century

at

Sicyon

{c.

655-556/5). Later tyrannies, like

modern ones, did not last so long. Aristotle put forward some reasons

for their long life: the tyrants respected the laws, treated their subjects

with moderation, forwarded the people's interests, and

in

the case

of

one man in each dynasty, Periander and Cleisthenes, were successful in

war

{Pol.

1315b!

3—30).

We may add others. The founder of a tyranny

was among the ablest of the oligarchs, and he eliminated any rivals by

execution

or

banishment. Some

of

his opponents preferred compro-

mise;

then they held positions in his service. The common people were

not immediately dangerous, nor

in

danger; they lacked weapons and

experience, lived out on the land (Arist.

Pol.

1305318), and were satisfied

if their betters gave them justice, peace

and

prosperity. Fortune

favoured

the

tyrants

in

that the period was one

of

rapidly growing

prosperity. They could keep their subjects prosperous and at the same

time use their own wealth to cultivate friends abroad and at home, and

to obtain the favour of'the media', Delphi and Olympia. Tyrant rarely

ate tyrant; for it was in their common interest to combine and keep the

emigres at arm's distance, especially since Megara, Corinth and Sicyon

formed

a

continuous area

of

tyrant-land, uniquely

at

peace with one

another for perhaps

a

century. There were other tyrannies of less fame

and shorter duration; among them Procles at Epidaurus, Leon at Phlius,

Pantaleon

at

Pisa, and one Hippias, perhaps

at

Megara but separated

from Theagenes by an interval

of

time.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PURSUIT OF POWER BY INDIVIDUALS 347

The tyrants

at

Corinth inherited

and

expanded

a

strong colonial

system. Corcyra, held at first by the exiled Bacchiadae, was brought into

the fold, and Corcyra and Corinth founded a joint colony at Epidamnus

c. 625. Colonies were planted by Corinth alone

or

in conjunction with

the local people

at

Leucas, Heraclea, Ambracia and Apollonia Illyrica

within

the

period c. 625-600. Three sons

of

Cypselus went

out as

founders and probably

as

rulers; thus

at

Ambracia Gorgus was suc-

ceeded

by at

least two 'tyrants'

of

the Cypselid house. The founder

of Epidamnus was a Corinthian, of

a

house 'descended from Heracles',

specially summoned from Corinth and therefore a collaborator with the

Cypselids; and the settlers were Corcyraeans in the main, but there were

also some Corinthians and others

of

Dorian race (Thuc.

1.

24.2).

As

the tyrants controlled the planting of colonies, we see that their policy

was pro-Dorian. Later in the rule of Periander the Corcyraeans rebelled

and killed Periander's son Lycophron; and when Periander regained

control

of

Corcyra,

he

sent three hundred boys, sons

of

leading

Corcyraeans, to Alyattes, king of Lydia, to be castrated (it was said) and

serve as eunuchs.

The control of the north-western area was of vital importance to the

Cypselids

and to

Corinth;

for

they drew from

it

silver, copper,

ship-building timber, hides, wool, milk-products and meat, quite apart

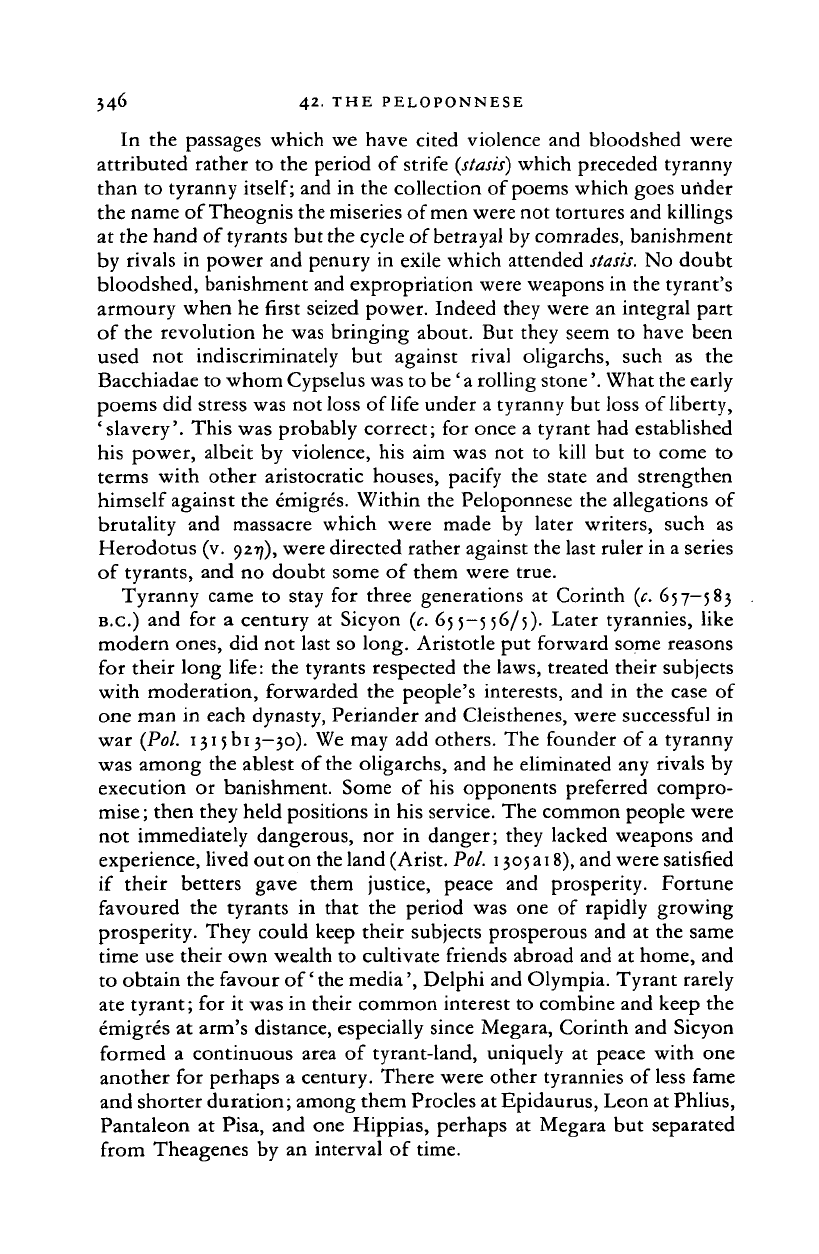

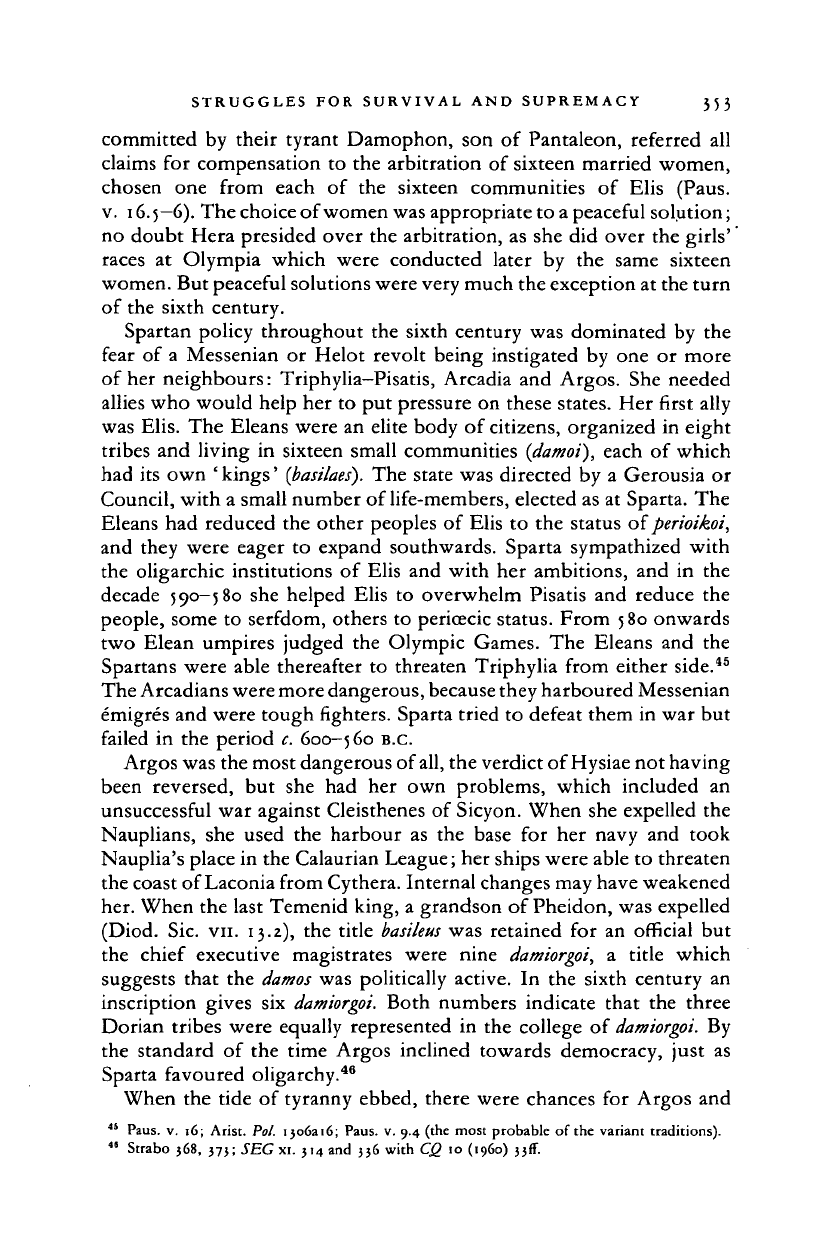

from the profits of trade with the west. A beautiful gold bowl, dedicated

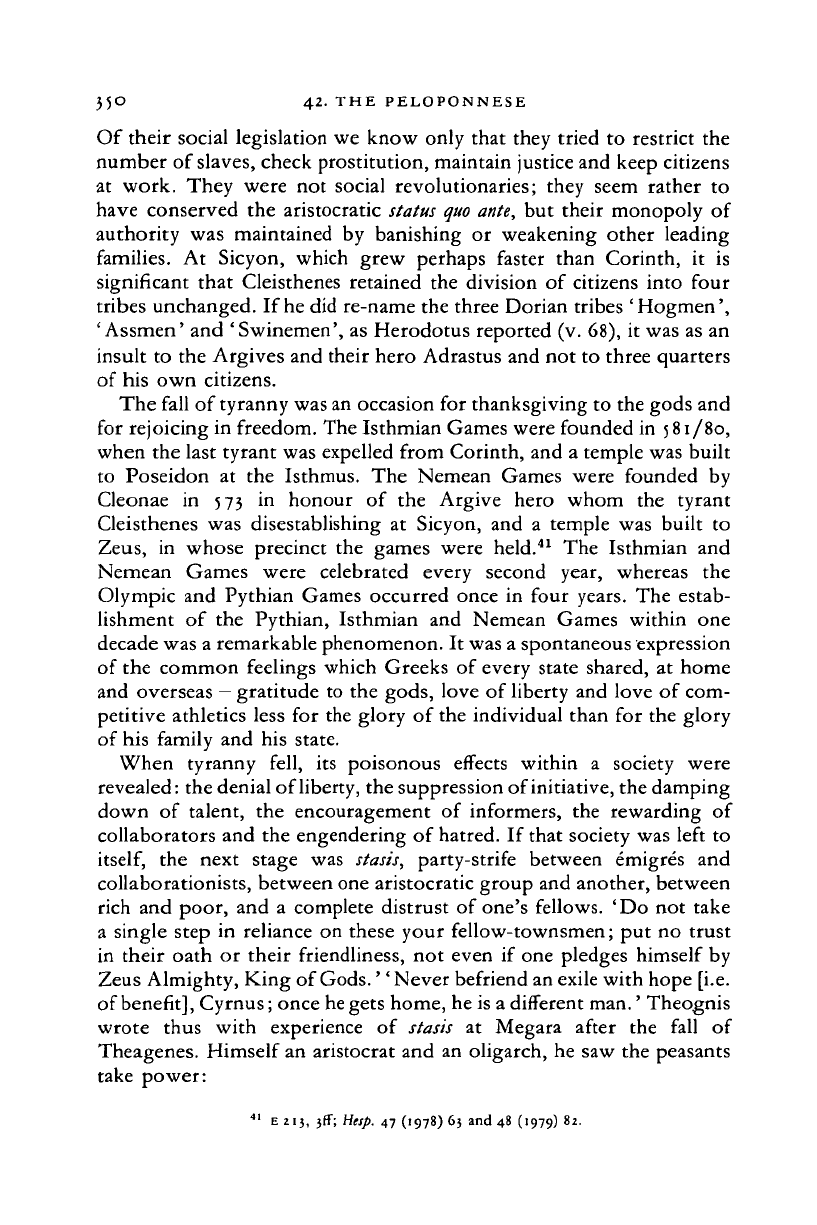

at Olympia by the Cypselids as spoils from Heraclea (fig. 51), reminds

us that the control even

of

their colonies was maintained

by

force

of

arms,

for

which sea power was

a

sine qua

non.

A

son

of

Periander led

a colony

to

Potidaea, which faced the Thermaic Gulf and served

the

Macedonian

end of the

trans-Balkan route

via

Lake Lychnitis

to

Epidamnus (see above, p. 133). The colonial policy

of

the tyrants was

of the greatest benefit not only to Corinth but also to other states which

profited from the resulting increase

in

the flow

of

trade.

One such beneficiary was Sicyon, famous

for

its bronzework.

The

wealth

of

its tyrants was displayed

to the

world

by

victories

in the

chariot race

at

Olympia by Myron

in

648 and later by Cleisthenes, and

at Delphi by Cleisthenes

in

582, and by the treasuries which they built

at these sanctuaries; that

at

Olympia was of bronze sheet, divided into

two rooms, one

in

Doric style and the other in Ionic, and the bronze

was said

to

have come from Tartessus

in

western Spain. Cleisthenes,

tyrant c. 600-570, was appointed

by the

Amphictions

of

Delphi

to

command their forces against Crisa

in

the Sacred War and was given

a third

of

the spoils (see above,

p.

313). Suitors

for the

hand

of

his

daughter were said

to

have come from

as far

afield

as

Sybaris

and

Epidamnus, and he held his own in

a

war against Argos. Never again

did Sicyon stand

so

high.

It

was only rarely that the tyrants led their

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

348

42.

THE PELOPONNESE

51.

Gold bowl - a deep phiale - found in the bed of the River Alpheus at Olympia.

Inscribed ?w/if AiSai aviBtv cf EpaxXeia; ' The sons of Cypselus dedicated this (as spoils)

from Heraclea.' Late seventh or early sixth century B.C. Width 168 cm. Weight 85647 g.

223 carat gold. (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 21.1843

'>

after

E l

i4< 9°> fy>- 56; 'bid. 257,

n. 348; CAH Plates i

1

274; A 36, 127-8.)

hoplite armies into war. They preferred a network of alliances, of

friendly relations with foreign rulers such as Alyattes of Lydia or

Psammetichus I of Egypt, and of ties by marriage, for instance linking

Theagenes and Cylon, and Cleisthenes and Megacles. Like the kings of

Macedon, the tyrants practised polygamy to secure a dynastic succession

and promote alliances, and there may have been some substance behind

the stories of fratricide, necrophily and incest which were told by

sensation-loving writers. At one time Periander was rated one of the

Seven Wise Men of the Greek world, and he was chosen to arbitrate

between Athens and Mytilene over Sigeum (Hdt. v. 95); but every sort

of crime was of course attributed to him by later writers.

We can infer from the wording of dedications how the tyrants wished

to represent their rule. The chest within which the founder, Cypselus,

was hidden as a baby was dedicated by 'the Cypselidae' in gratitude

for his salvation by Zeus of Olympia (Paus. v. 17.5). And in the colonial

field it was ' the Cypselidae' who dedicated the golden bowl from spoils

won at Heraclea (fig. 51). Thus the change from the Bacchiadae to the

Cypselidae was a change not of principle but of family, and it seems

from the story in Herodotus in.

5

2.4 that the men of the tyrannical

house at Corinth and in some colonies were styled 'kings'

[basileis).

The

Sicyonian treasury at Olympia was dedicated by ' Myron and the people

{demos)

of the Sicyonians', which implied a

basileus

in office and a

meeting of the citizen body of Sicyon.

39

In the eyes of the rulers and

most of the citizens tyranny was not so much an intermission of

constitutional government as a system of very long duration, blessed

39

SEC 1. 94 and E 228, 517 n. 1; Paus. vi. 19.4, whereas Paus. vi. 19.1 is a paraphrase.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PURSUIT

OF

POWER

BY

INDIVIDUALS

349

i^^^^^^^^Sr*.

52.

The

diolkos

at the

Corinthian Isthmus.

>

Sixth, century B.C.(After

N.

Verdelis,

Atbenische Mitttilungen

73

(1958) Beil.

106.)

by Delphi

and

Olympia, internationally recognized,

and

crowned with

a material success which seemed

to be a

sign

of

divine favour.

The

origins

of

Cypselus were sanctified

by

oracular utterances

and by

a

Moses-like myth (Hdt.

v.

92), which hints

of

some

ruler-cult

at

Corinth,

and nobles

may

have regarded

the

ruling tyrant rather

as

Pindar

regarded Hieron

of

Syracuse. Poets such

as

Arion, Chersias

and

Epigenes sang

the

tyrants' praises

at

Corinth,

and

Cleisthenes promoted

the performance

of

'tragic choruses'

at

Sicyon.

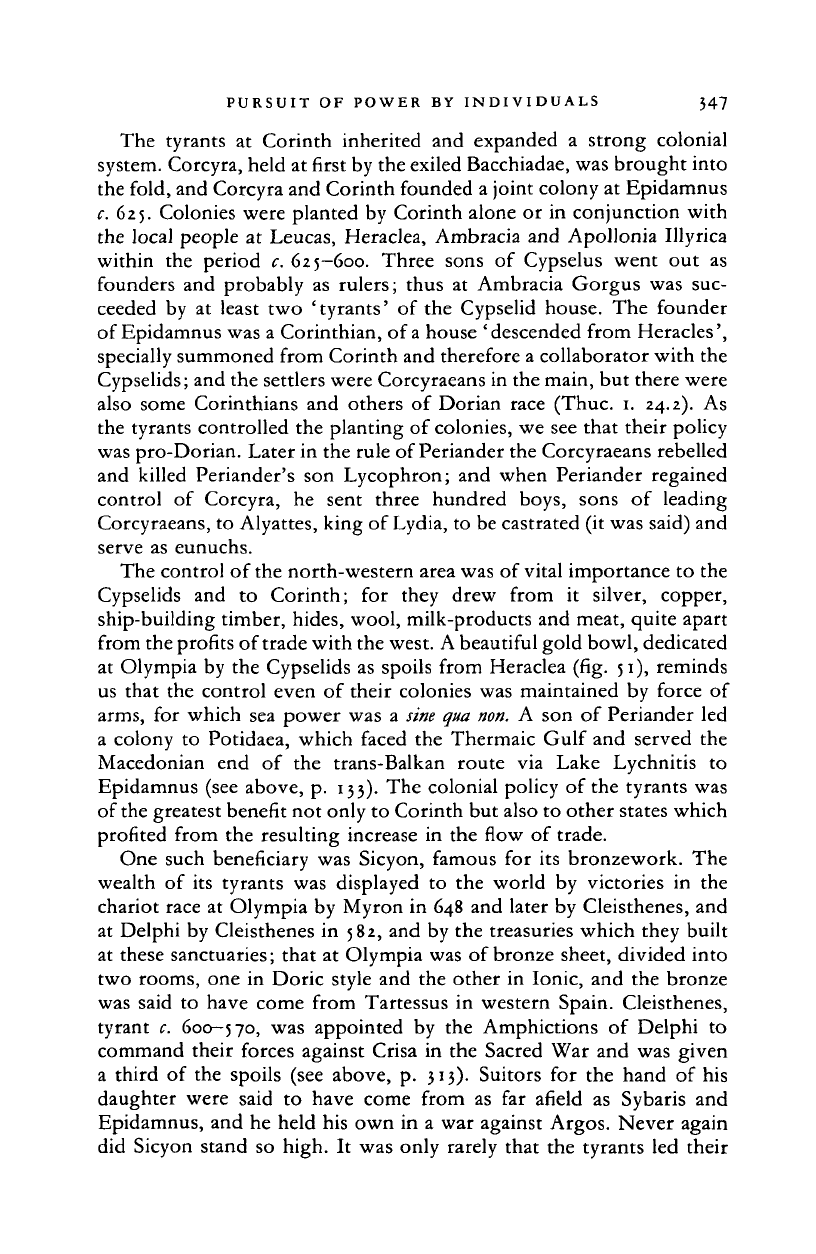

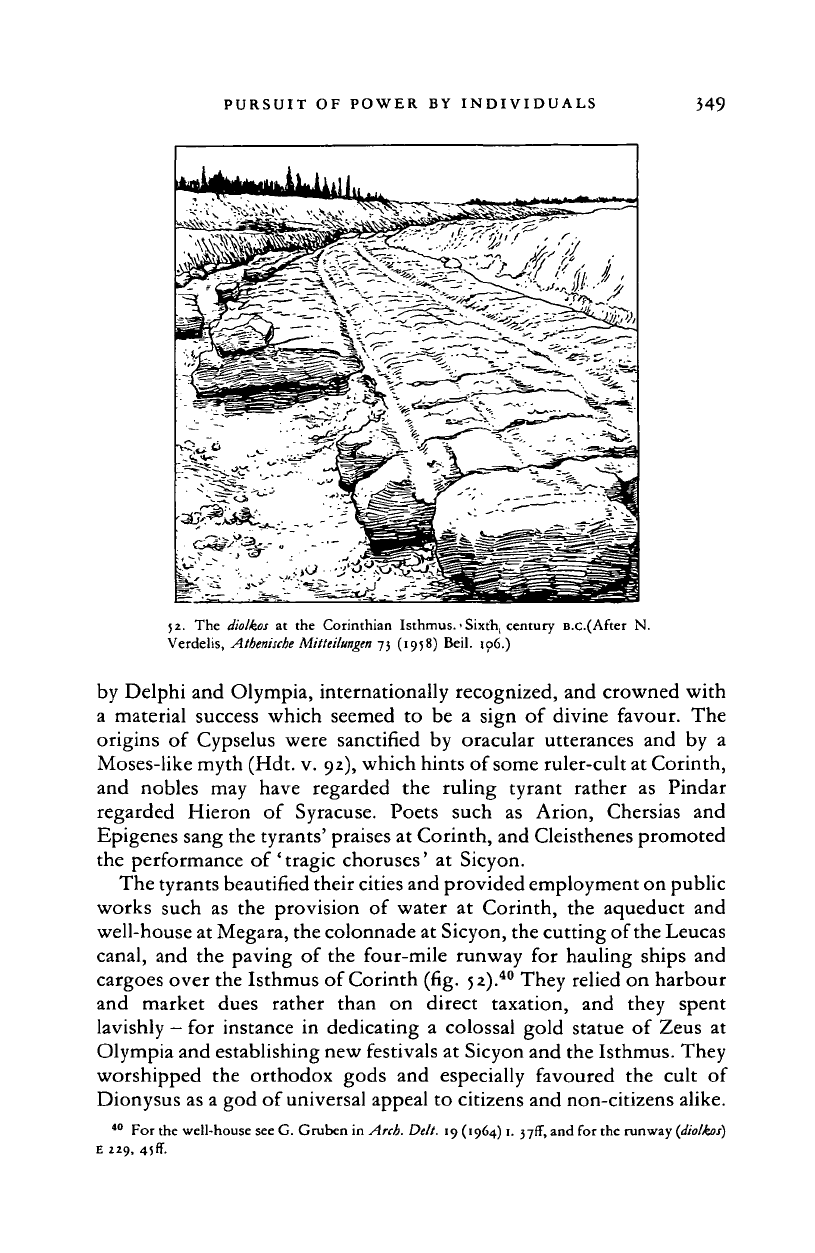

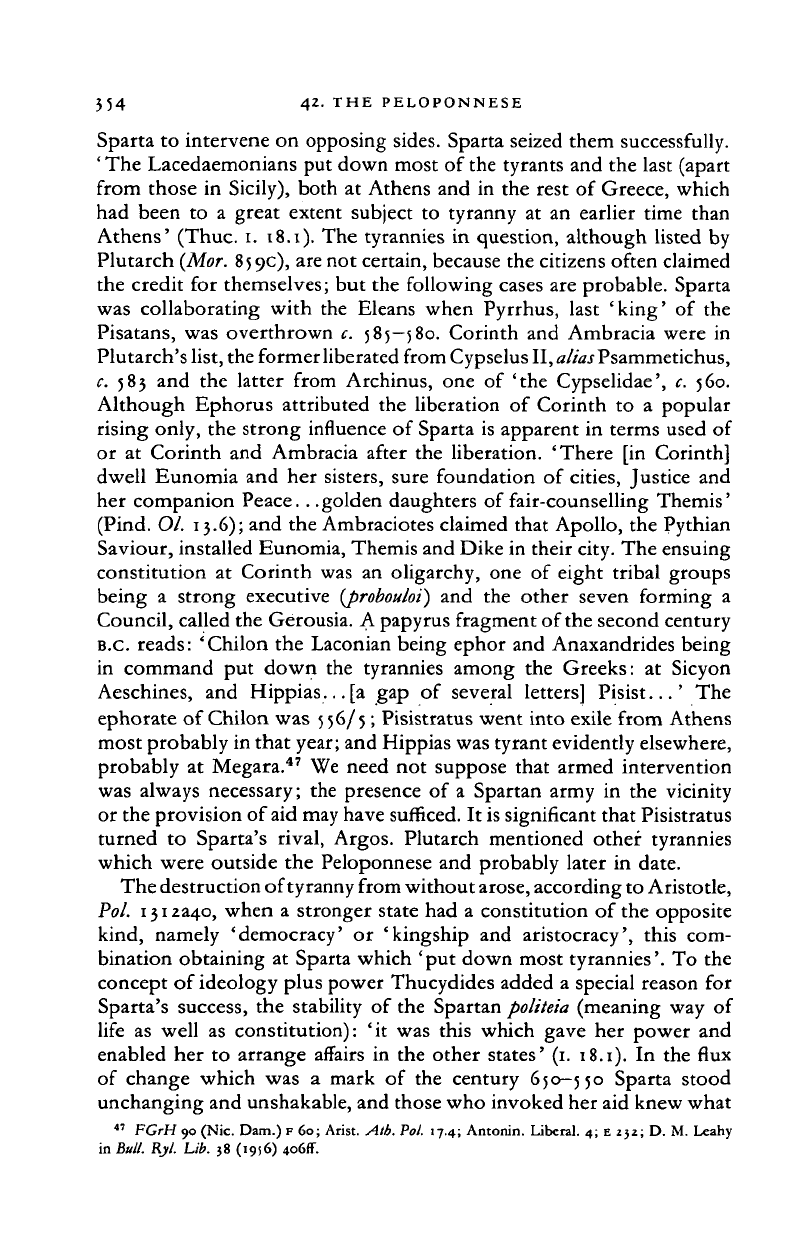

The tyrants beautified their cities and provided employment on public

works such

as the

provision

of

water

at

Corinth,

the

aqueduct

and

well-house

at

Megara, the colonnade

at

Sicyon, the cutting of the Leucas

canal,

and the

paving

of the

four-mile runway

for

hauling ships

and

cargoes over

the

Isthmus

of

Corinth

(fig.

52).

40

They relied

on

harbour

and market dues rather than

on

direct taxation,

and

they spent

lavishly

—

for

instance

in

dedicating

a

colossal gold statue

of

Zeus

at

Olympia

and

establishing new festivals

at

Sicyon

and the

Isthmus. They

worshipped

the

orthodox gods

and

especially favoured

the

cult

of

Dionysus as

a god of

universal appeal

to

citizens

and

non-citizens alike.

40

For the

well-house see

G.

Gruben

in

Arch. Delt. 19 (1964)

1.

37ff, and for the

runway

{diolkos)

E 229,

4jff.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

35° 4

2

-

THE

PELOPONNESE

Of their social legislation we know only that they tried to restrict the

number of slaves, check prostitution, maintain justice and keep citizens

at work. They were not social revolutionaries; they seem rather to

have conserved the aristocratic status

quo

ante,

but their monopoly of

authority was maintained by banishing or weakening other leading

families.

At

Sicyon, which grew perhaps faster than Corinth,

it is

significant that Cleisthenes retained the division of citizens into four

tribes unchanged. If he did re-name the three Dorian tribes 'Hogmen',

'Assmen' and 'Swinemen', as Herodotus reported (v. 68), it was as an

insult to the Argives and their hero Adrastus and not to three quarters

of his own citizens.

The fall of tyranny was an occasion for thanksgiving to the gods and

for rejoicing in freedom. The Isthmian Games were founded in 581/80,

when the last tyrant was expelled from Corinth, and a temple was built

to Poseidon

at

the Isthmus. The Nemean Games were founded by

Cleonae

in

573

in

honour

of

the Argive hero whom the tyrant

Cleisthenes was disestablishing at Sicyon, and

a

temple was built to

Zeus,

in

whose precinct the games were held.

41

The Isthmian and

Nemean Games were celebrated every second year, whereas

the

Olympic and Pythian Games occurred once in four years. The estab-

lishment of the Pythian, Isthmian and Nemean Games within one

decade was a remarkable phenomenon. It was a spontaneous expression

of the common feelings which Greeks of every state shared, at home

and overseas

-

gratitude to the gods, love of liberty and love of com-

petitive athletics less for the glory of the individual than for the glory

of his family and his state.

When tyranny fell, its poisonous effects within

a

society were

revealed: the denial of liberty, the suppression of initiative, the damping

down

of

talent, the encouragement of informers, the rewarding of

collaborators and the engendering of hatred. If that society was left to

itself,

the next stage was stasis, party-strife between emigres and

collaborationists, between one aristocratic group and another, between

rich and poor, and a complete distrust of one's fellows. 'Do not take

a single step in reliance on these your fellow-townsmen; put no trust

in their oath or their friendliness, not even if one pledges himself by

Zeus Almighty, King of Gods.'' Never befriend an exile with hope [i.e.

of

benefit],

Cyrnus; once he gets home, he is a different man.' Theognis

wrote thus with experience

of

stasis

at

Megara after the fall

of

Theagenes. Himself an aristocrat and an oligarch, he saw the peasants

take power:

41

E 213, 3(f; Hesp. 47 (1978) 63 and 48 (1979) 82.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

STRUGGLES FOR SURVIVAL AND SUPREMACY 351

Cyrnus, this city is

a

city still but the people are indeed different. Hitherto they

had no knowledge of

law

or

justice,

but lived

like

deer outside this

city,

wearing

goatskin on their

backs.

They're your nobles now, son of

Polypaiis!

The good

men of old are worthless now.

42

Others saw in this regime a very early example of democracy, radical,

unbridled and short-lived (Plut.

Quaest.

Graec.

18). The swing of

stasis

brought the oligarchs into power in their turn; and in the end another

tyrant

arose.

In this we

see

an early example of the disease of the city-state,

which was ultimately to reduce its ability to resist foreign aggression.

But in the mid-sixth century the Dorian states were not left to them-

selves. Sparta, exempt from tyranny

herself,

intervened.

IV. STRUGGLES FOR SURVIVAL AND SUPREMACY,

C. 650-530 B.C.

Defeated by Argos at Hysiae, Sparta sank to her nadir in the so-called

Second Messenian War, which lasted perhaps thirty years or more. We

have some contemporary evidence in the poems of Tyrtaeus; for his

traditional floruit, 640—637 B.C., was early in the war. That the fighting

was carried into Laconia and that the power of Sparta was almost broken

is clear from his poems, in which the choice for the Spartan was to lose

his life or lose his land:

To die, falling in the forefront of

the

fray, is honourable in

a

good soldier who

fights for his fatherland. But to live a beggar's life, losing his city and fertile

fields and wandering with his dear mother, aged father, little children and

wedded wife, is of all things most miserable.

Take heart, for you are the stock of Heracles the invincible; Zeus has not yet

turned his head away. Flinch not, fear not the masses of men, but let each bear

his shield straight into the forefront, counting life his enemy and the black

spirits of Death as dear as the rays of the sun.

In the crisis of the war Tyrtaeus told of 'the battle by the trench',

the Spartan line being drawn up in front of it. To later generations

it

was the typical disposition

in

which, there being no way

of

retreat,

soldiers fought to win or die perforce; and it was conjectured that there

were freed Helots in the Spartan line on that occasion. That Sparta was

almost overcome was due to the help which the Messenians obtained

from Argos, Elis and Pisatis at the start, and it was these troops which

used the hoplite tactics which Tyrtaeus described. The Arcadians,

it

seems, joined the Messenians later.

In

any case the Spartan line won

42

Theognis a83~6, 533-4, 53-8;

see

M. L. West, Studies in Greek Elegy (Berlin, 1974)

4iff.

Popular government ensued also at Ambracia for a time (Arist. Pol. 1304231).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

}52 4

2

- THE PELOPONNESE

'the battle

by the

trench',

and

from then

on

Sparta slowly gained

the

upper hand.

43

Memories

of

the last stage

of

the war have come down through late

authors. When the Messenians were defending their last stronghold on

Mt

Ira in

northern Messenia,

the

Arcadians

and 'the

Pylians' helped

them;

but

Sparta obtained

aid

from Elis, Corinth

and

Samos

(the

last

providing ships,

Hdt.

in. 47.1). When defeat came, some Messenians

fled to Arcadia. Pylus

and

Methone fell probably later;

and

some

refugees from there went to colonies in the west, such as Metapontum.

44

The Spartans left Pylus desolate but gave the site of Methone to refugees

from Nauplia. During the latter part

of

the war Sparta inflicted defeats

on Argos, which

led to the

people banishing

the

last Temenid king,

Meltas,

a

grandson

of

Pheidon,

and

it

was

after this that Argos

destroyed Nauplia

on

the ground of'Laconizing'. Sparta entered

the

sixth century with the confidence

of

a hard-won victory, the extension

of

her

conquests

in

the

south-western Peloponnese,

and two

useful

allies,

Elis

and

Corinth.

The

influence

of

Tyrtaeus was

to be as

long-

lasting

at

Sparta

as

that

of

Solon

at

Athens;

and his

poems called

upon

the

Spartans

to be

loyal

to the

constitution

in its

classical form,

the Eunomia including

the

Rider

to the

Rhetra.

The First Sacred

War

shows

the

military power

of a

widespread

coalition. After its victory,

in

5

90,

the Delphic Amphictiony expanded

by bringing the Dorian states

of

the Peloponnese into

its

membership,

and

all

members took

a

new oath

'not to lay

waste any Amphictionic

city nor cut

it off

from running water in war or peace' (Aeschin. 2.115).

That representatives

of

most states

of

mainland Greece should meet

in

time

of

peace,

put

a

ban on

some methods

of

war

and

agree

to

take

joint action against

an

offender,

was

indeed

a

most remarkable

development. Hitherto each state

had

acted

as

it

alone pleased;

now

international discussion and agreement were shown

to

be possible.

The

Amphictionic oath

was

a

reaction against total warfare

and

total

destruction,

as

practised

in the

Peloponnese

and

elsewhere. Another

sign

of

the times was arbitration

to

avoid war. Periander,

for

instance,

arbitrated between Athens and Mytilene

for

the possession

of

Sigeum,

and Sparta between Athens and Megara

for

the possession

of

Salamis.

The Eleans, having decided

to

dissociate

the

Pisatans from

the

crimes

43

For the trench Arist. Elb. Nic. iu6aj6 with Schol.; Tyrt.

fr.

10, col. 4, line 40 (ed. Prato);

for Helots Paus. iv. 16.6 and Oros. 1. 21.7; for allies Strabo 562, not emending the text, and Paus.

vni.

39.3-4 dating to 659 B.C. earlier clashes between Sparta and Arcadian cities. Suda

s.v.

Tyrtaios

gives the date, and Plut. Mor. 194B puts the end c. 600 B.C. See POxy 47 no. 3316.

44

Details are uncertain because on the liberation

of

the Messenians

in

the fourth century B.C.

attempts

to

provide them with an early history were made by Callisthenes (FGrH 124 F 23) and

Ephorus (FGrH 70

p n

j), and later by Rhianus and Myron (Paus. iv. 6.1-4), and Apollodorus

(FGrH 244 F 334). See E 166,

ijff;

E 174; and E 183, 44.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

STRUGGLES FOR SURVIVAL AND SUPREMACY 353

committed by their tyrant Damophon, son

of

Pantaleon, referred

all

claims for compensation to the arbitration of sixteen married women,

chosen

one

from each

of the

sixteen communities

of

Elis (Paus.

v.

16.5—6).

The choice of women was appropriate to a peaceful solution;

no doubt Hera presided over the arbitration, as she did over the girls'

races

at

Olympia which were conducted later

by the

same sixteen

women. But peaceful solutions were very much the exception at the turn

of the sixth century.

Spartan policy throughout the sixth century was dominated by the

fear

of

a Messenian

or

Helot revolt being instigated by one

or

more

of her neighbours: Triphylia—Pisatis, Arcadia and Argos. She needed

allies who would help her to put pressure on these states. Her first ally

was Elis. The Eleans were an elite body of citizens, organized in eight

tribes and living

in

sixteen small communities

(damoi),

each of which

had its own 'kings'

(basilaes).

The state was directed by a Gerousia or

Council, with a small number of life-members, elected as at Sparta. The

Eleans had reduced the other peoples of Elis to the status of perioikoi,

and they were eager to expand southwards. Sparta sympathized with

the oligarchic institutions

of

Elis and with her ambitions, and

in

the

decade 590-580 she helped Elis

to

overwhelm Pisatis and reduce the

people, some to serfdom, others to pericecic status. From 580 onwards

two Elean umpires judged the Olympic Games. The Eleans and the

Spartans were able thereafter to threaten Triphylia from either side.

45

The Arcadians were more dangerous, because they harboured Messenian

emigres and were tough fighters. Sparta tried to defeat them in war but

failed in the period c. 600—560

B.C.

Argos was the most dangerous of

all,

the verdict of Hysiae not having

been reversed,

but

she had

her

own problems, which included

an

unsuccessful war against Cleisthenes of Sicyon. When she expelled the

Nauplians, she used the harbour as the base

for

her navy and took

Nauplia's place in the Calaurian League; her ships were able to threaten

the coast of Laconia from Cythera. Internal changes may have weakened

her. When the last Temenid king, a grandson of Pheidon, was expelled

(Diod. Sic.

VII.

13.2), the title

basileus

was retained for an official but

the chief executive magistrates were nine

damiorgoi,

a

title which

suggests that the

damos

was politically active.

In

the sixth century an

inscription gives six

damiorgoi.

Both numbers indicate that the three

Dorian tribes were equally represented in the college of

damiorgoi.

By

the standard

of

the time Argos inclined towards democracy, just

as

Sparta favoured oligarchy.

46

When the tide of tyranny ebbed, there were chances for Argos and

46

Paus.

v.

16; Arist. Pol. 1306316; Paus.

v.

9.4 (the most probable

of

the variant traditions).

" Strabo 368, 373;

SEG

xi. 314 and 336 with

CQ io

(i960) 33IT.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

354 4

2

-

THE

PELOPONNESE

Sparta

to

intervene

on

opposing sides. Sparta seized them successfully.

' The Lacedaemonians put down most

of

the tyrants

and

the last (apart

from those

in

Sicily), both

at

Athens

and in the

rest

of

Greece, which

had been

to a

great extent subject

to

tyranny

at an

earlier time than

Athens' (Thuc.

i.

18.i).

The

tyrannies

in

question, although listed

by

Plutarch

(Mor.

859c), are not certain, because the citizens often claimed

the credit

for

themselves;

but

the following cases are probable. Sparta

was collaborating with

the

Eleans when Pyrrhus, last 'king'

of the

Pisatans,

was

overthrown c. 585—580. Corinth

and

Ambracia were

in

Plutarch's list, the former liberated from Cypselus II,a//aj-Psammetichus,

c.

583 and the

latter from Archinus,

one of 'the

Cypselidae',

c. 560.

Although Ephorus attributed

the

liberation

of

Corinth

to a

popular

rising only,

the

strong influence

of

Sparta

is

apparent

in

terms used

of

or

at

Corinth

and

Ambracia after

the

liberation. 'There

[in

Corinth]

dwell Eunomia

and her

sisters, sure foundation

of

cities, Justice

and

her companion Peace... golden daughters

of

fair-counselling Themis'

(Pind. Ol. 13.6);

and

the Ambraciotes claimed that Apollo,

the

Pythian

Saviour, installed Eunomia, Themis and Dike

in

their city. The ensuing

constitution

at

Corinth

was an

oligarchy,

one of

eight tribal groups

being

a

strong executive

(probouloi)

and the

other seven forming

a

Council, called the Gerousia. A papyrus fragment of the second century

B.C. reads: 'Chilon

the

Laconian being ephor

and

Anaxandrides being

in command

put

down

the

tyrannies among

the

Greeks:

at

Sicyon

Aeschines,

and

Hippias... [a

gap of

several letters] Pisist...'

The

ephorate

of

Chilon was 556/5; Pisistratus went into exile from Athens

most probably in that year; and Hippias was tyrant evidently elsewhere,

probably

at

Megara.

47

We

need

not

suppose that armed intervention

was always necessary;

the

presence

of a

Spartan army

in the

vicinity

or the provision

of

aid may have sufficed.

It

is significant that Pisistratus

turned

to

Sparta's rival, Argos. Plutarch mentioned other tyrannies

which were outside

the

Peloponnese

and

probably later

in

date.

The destruction of tyranny from without

arose,

according to Aristotle,

Pol. 1312340, when

a

stronger state

had a

constitution

of

the opposite

kind, namely 'democracy'

or

'kingship

and

aristocracy', this

com-

bination obtaining

at

Sparta which

'put

down most tyrannies'.

To the

concept

of

ideology plus power Thucydides added

a

special reason

for

Sparta's success,

the

stability

of

the Spartan

politeia

(meaning

way of

life

as

well

as

constitution):

'it was

this which gave

her

power

and

enabled

her to

arrange affairs

in the

other states' (1. 18.1).

In the

flux

of change which

was a

mark

of the

century 650—550 Sparta stood

unchanging and unshakable, and those who invoked her aid knew what

" FGrH 90 (Nic. Dam.)

F

60; Arist.

Atb.

Pol. 17.4; Antonin. Liberal.

4;

E

232;

D. M.

Leahy

in

hull.

Rjl. Lib. 38

(1956)

4o6ff.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008