Boardman J., Hammond N.G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

STRUGGLES FOR SURVIVAL AND SUPREMACY 355

they would

get for the

foreseeable future: support

for

oligarchy

and

troops

to

maintain

it, if

necessary.

By

mid-century Sparta succeeded

admirably;

for she

exercised

an

indirect control over Pisatis, Elis,

Sicyon, Corinth, Megara and perhaps some other states, and she kept

Argos almost in isolation. The ephor Chilon, generally acclaimed as one

of

the

Seven Wise Men of this age, may have formulated the policy. His

suspicions of Argos appeared in his saying that Cythera would be better

sunk beneath

the

waves (Hdt.

vn.

235.2),

and he

may have initiated

another system

of

indirect control which began

in

connexion with

Arcadia.

A Pythian oracle explained

to the

Spartans their failure

to win

victories over the Arcadians on the ground that the Arcadians were too

numerous, but went

on in

hexameter verse

as

follows:

I shall give thee to dance

in

Tegea, with noisy footfall,

and with the measuring line mete out the glorious champaign.

Sparta then attacked Tegea, bringing fetters

to

bind the Tegeans and

rods

to

measure

the new

lands.

Yet

another defeat;

and it was the

Spartans who wore the fetters and worked the land as prisoners of war

(the very fetters were later preserved

in the

temple

of

Athena Alea

at

Tegea). Sparta enquired again at Delphi and was told to obtain the bones

of Orestes, son

of

Agamemnon, and become 'the protector of Tegea'.

But where were the bones? The story should be read in Herodotus

1.

6yf.

Once Sparta

had the

sacred relics

and

understood

the

significance

of

the oracle, she ceased

to

smite the Arcadians as all Dorians had done,

and

she

offered herself as their protector.

So

Sparta

and

Tegea came

to terms, and when the other Arcadians joined them Sparta could count

on their

aid

against Argos,

if

the need should arise.

The treaty

of

reconciliation was inscribed

by

Sparta and Tegea

on

a stele on the bank of the Alpheus. Of its terms two were reported (not

verbatim) and explained by Aristotle (fr. 592): 'to expel the Messenians

from the land and not to be allowed to make (men) blessed' (xprjorovs,

i.e. dead). The expulsion

of

the Messenians was the first step towards

establishing a

cordon sanitaire

round Sparta's territory. As interpreted by

Aristotle, who may have seen the original in full, the ban on the capital

sentence was in the interest of those Tegeans who 'Laconized', i.e. who

fostered the interest

of

Sparta; and

a

century later Athens was

to

take

similar steps

to

protect

her

sympathizers

in the

subject states

of

her

empire, nominally

her

'allies'.

48

Sparta's offers

of

similar alliances

to

other states in the Peloponnese were widely accepted. We do not know

the conditions

but we can

infer from later circumstances that they

48

For the

oracles

see

A

50, 1

ioif;

for

'blessed' being

a

euphemism

for

'dead' compare

in

modern Greek 'makariles'';

for

other interpretations see E 166,

iyf.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

356 4

2

-

THE

PELOPONNESE

included expulsion of Messenian refugees, perhaps an undertaking to

help Sparta in the event of a Helot revolt, and acceptance of Sparta's

command in a joint war. This right of command

{hegemonid)

was

unrestricted; thus the king or kings in command did not necessarily

reveal the objective of

a

joint campaign. The advantages to Sparta were

the indirect control of wide areas, the addition to her armed forces of

a large reserve, and the buttressing of her own social system; and the

advantages to an ally were peace with Sparta, defence of its territory

by Sparta if it was threatened by an aggressor, and in particular defence

against Argos. The cost to Sparta was negligible, because she maintained

her superb army on a war footing in any case, and the cost to the ally

was not definable in terms of goods or services or bases, its army being

called out only against an aggressor, but consisted of the acceptance of

Sparta's indirectly applied political influence in favour of a 'Laconizing'

oligarchy.

After the inauguration of this policy of alliance

c.

560 B.C., Sparta set

herself up both as a liberator from tyranny and as a protector against

aggression, and she brought into her fold by 550 Elis, Arcadia, Sicyon,

Corinth and Megara, and perhaps Phlius and Cleonae. The resultant

group of states was called literally ' The Lacedaemonians and the allies',

i.e. the allies each of Sparta, not the allies of one another; and it went

into action contractually in response to attack from an aggressor. ' The

Spartan Alliance' is a better abbreviation for us than the current one,

'The Peloponnesian League', because it is closer to the Greek phrase

and has no geographical limit. After

5 5 5

the bones of Tisamenus, son

of Orestes, were brought from Helice to Sparta in an attempt to win

over the Achaeans (with what result is not known), and the opprobrious

names were retained at Sicyon as a continuing insult to Argos.

Sparta now felt strong enough to challenge Argos. She drove the

Argives out of Cythera and the east coast of what was henceforth called

Laconia (replacing Prasiae there as a member of the Calaurian League),

and advanced into Thyreatis, where the Argive army stood its ground.

Sparta did not call upon her

allies.

It was to be

a

battle of prestige. Three

hundred champions from each side were to decide by combat who

should possess Thyreatis. At nightfall, which ended the fighting, only

two Argives and one Spartan were left alive; the Argives ran home and

reported their victory, but the Spartan took the spoils of the Argive

dead to his camp. Next day the main armies returned to see what had

happened, and neither being prepared to concede defeat they set to in

earnest. Both sides suffered heavy losses, but Sparta won. It was the

final break through. She was now (546) acknowledged as the leading

power in Greece, and the victory was celebrated in perpetuity by a

special religious festival.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

STRUGGLES FOR SURVIVAL AND SUPREMACY 357

In

the

second half

of

the century

the

yardstick

of

Sparta's influence

was

the

strength

of

the Spartan Alliance,

not

that

of

Sparta alone.

Its

potential

on

land

was

unrivalled.

At sea

Sicyon, Corinth

and

Megara

controlled the western approaches and the Isthmus, and Sparta, having

acquired Cythera and Pylus, straddled the coastal routes from the west

and

the

south.

49

In the

northern Aegean Corinth

and in the

Propontis

Megara

had

naval bases

in

their colonies,

and

towards

the

south-east

Aegina was a leading trader, with special rights at Naucratis;

for

Aegina

seems to have transferred her friendship from Argos to Sparta sometime

after

546. In

view

of the

wide contacts

of the

Spartan Alliance

the

ancient tradition

may be

accepted that Sparta

was

responsible

for the

overthrow of tyrants ultimately in Phocis, Thessaly, Thasos, Naxos and

Miletus, especially as

the

expedition which she and Corinth undertook

against Polycrates

of

Samos

c.

5 24

is well attested. Farther afield Sparta

became the ally

of

Croesus

of

Lydia, the self-appointed protector

of

the

Greeks against Cyrus

of

Persia

and the

friend

of

Amasis

of

Egypt.

It

was a fortunate coincidence that when Cyrus was laying the foundations

of the Persian empire Sparta was creating

a

loosely-articulated system

of power which was based

on

two principles,

a

coalition

of

free states

and

a

detestation

of

despotism.

Within

the

extraordinarily mobile world

of

city-states any combina-

tion of political power and economic prosperity attracted talent from

far

afield. Thus

in

650-550 Sparta became one

of

the leading centres

of

art,

literature

and

music.

The

temple

of

Athena Poliouchus was decorated

with bronze sheeting

(and so

known

as

Chalcioecus)

to the

design

of

Gitiadas,

a

local bronzeworker

and

poet;

the

early temple

of

Artemis

Orthia was replaced

by a

temple

in

limestone

of

Doric style;

the

Scias,

a meeting-hall

for

assemblies,

was

built

by a

Samian Theodorus,

and

the throne of Apollo

at

Amyclae by Bathycles and his team

of

craftsmen

from Magnesia in Asia Minor; and

a

shrine in stone was erected to Helen

and Menelaus

at

Therapne. The Laconian bronzeworkers were famous

for their statuettes and vessels, which were often dedicated

at

Olympia

or exported

to

distant markets, and they maintained their high standard

to

the end of

the sixth century. Although statuettes

in

ivory, jewellery

in gold, silver and amber, masks

in

clay and figurines

in

lead were only

of moderate quality, Laconian vase-painting rivalled that

of

Corinth.

Alcman, probably

a

Lydian

by

birth, made Sparta

his

home,

and

Stesichorus

of

Himera

and

Theognis

of

Megara stayed

at

Sparta.

We

see from their poems Sparta's delight in music and dancing, in the beauty

of girls

and

boys,

and in

their

own

countryside;

for

example,

in

Alcman's

Partheneion

or

these lines

of

Theognis (879-84):

" Corinth

and

Sparta were influential

in

the west

(cf.

Strabo 261

for

Locri's appeal

to

Sparta),

and Sparta

had

settlers

of

Laconian descent

in

Cyrene.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

358 4

2

' THE PELOPONNESE

Drink the wine my vines brought

me

from under the peaks of

Taygetus,

vines

old Theotimus, beloved of

the

gods,

planted

in

the mountain

glens

and brought

them the chill water from Platanistous. Drink

thereof!

You will shake off the

burden of sorrows and be light of heart instead, once you put on the armour

of liquor.

Alcman and Stesichorus were pioneers in choral lyric and developed

the literary Doric dialect which became standard for choral performances,

even in Attic tragedy later on. Choirs sang dancing or standing, as the

subject demanded, and the poet composed their music and that of

the accompanying instrument, using the lyre, in what was known as

the Dorian mode; like the poems of Tyrtaeus, this mode was said to

express courage and restraint.

At first Argos led the way in sculpture, as we see from the remarkable

statues of Cleobis and Biton, and perhaps in temple architecture at the

Heraeum, where a stone stylobate with widely-spaced column bases

carried a wooden superstructure, and

a

seventh-century stoa had capitals

of

a

very early kind; and

a

splendid clay mask was found at Tiryns. But

as its prosperity grew Corinth overhauled Argos for intance in the

development of terracotta tiles and finials, and the temple of Apollo of

about

5

50

B.C.

was a classic example of the early Doric order, built in

limestone with monolithic columns (of which seven survive); it had a

peristyle colonnade of

15

x

6

columns. Sanctuaries of Demeter and Kore

(early seventh century) and of Aphrodite (later in the century) lay by

and on the Acrocorinth, rather as meeting places for worshippers than

as homes for a god or goddess. For the enlarged city the provision of

water at the 'Fountain of Pirene' was achieved by a network of tunnels

with manholes, nearly a mile in length. In painted pottery Corinth was

pre-eminent until mid-century, after which Athens surpassed her, even

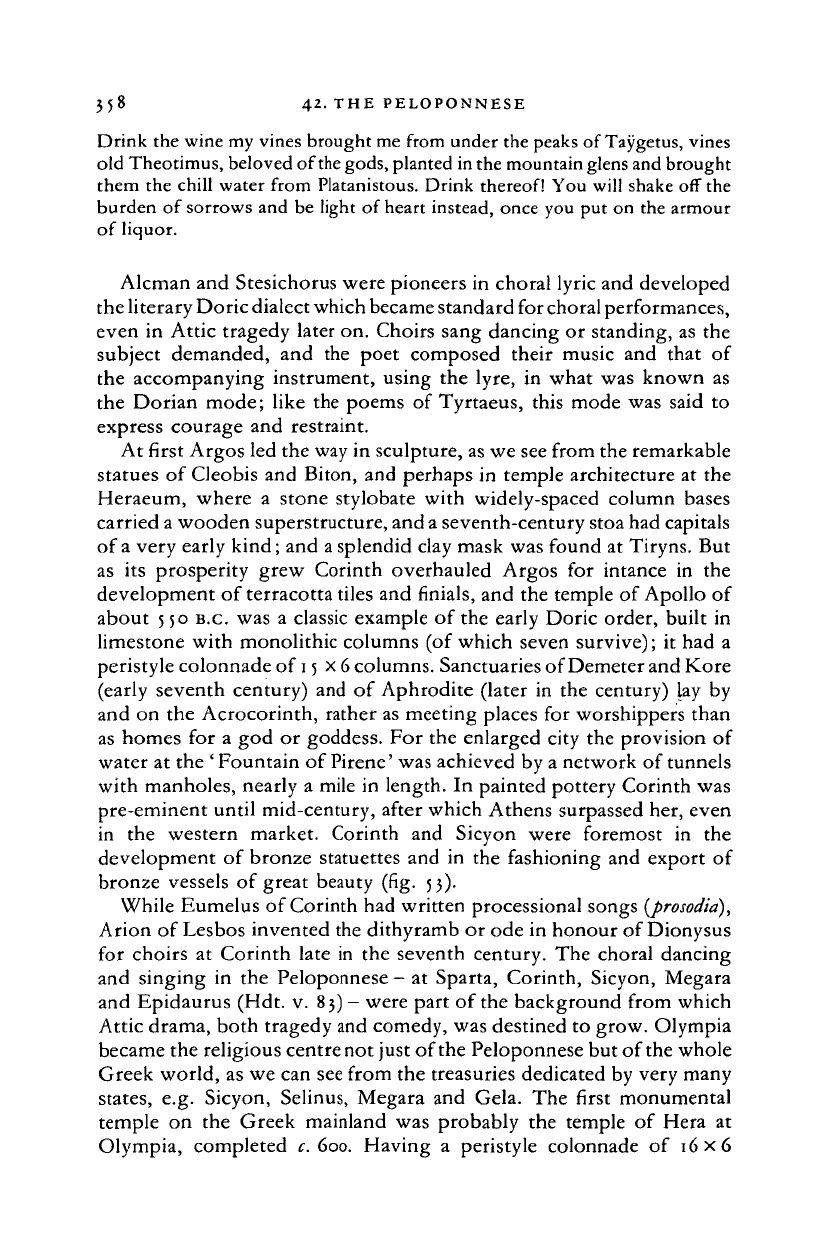

in the western market. Corinth and Sicyon were foremost in the

development of bronze statuettes and in the fashioning and export of

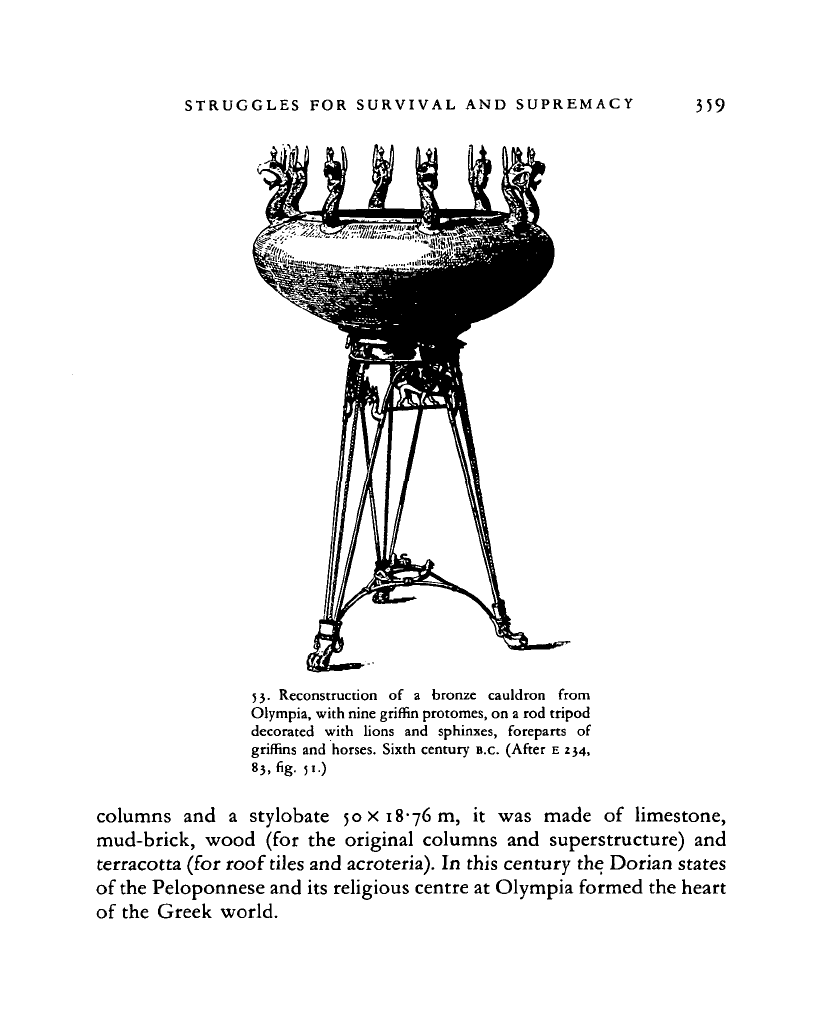

bronze vessels of great beauty (fig. 53).

While Eumelus of Corinth had written processional songs

(prosodia),

Arion of Lesbos invented the dithyramb or ode in honour of Dionysus

for choirs at Corinth late in the seventh century. The choral dancing

and singing in the Peloponnese

—

at Sparta, Corinth, Sicyon, Megara

and Epidaurus (Hdt. v. 83)

—

were part of the background from which

Attic drama, both tragedy and comedy, was destined to grow. Olympia

became the religious centre not just of the Peloponnese but of

the

whole

Greek world, as we can see from the treasuries dedicated by very many

states,

e.g. Sicyon, Selinus, Megara and Gela. The first monumental

temple on the Greek mainland was probably the temple of Hera at

Olympia, completed c. 600. Having a peristyle colonnade of 16x6

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

STRUGGLES FOR SURVIVAL AND SUPREMACY 359

53.

Reconstruction of a bronze cauldron from

Olympia, with nine griffin protomes, on a rod tripod

decorated with lions and sphinxes, foreparts of

griffins and horses. Sixth century B.C. (After E 234,

83,

fig. 51.)

columns and a stylobate 50 x 18-76 m, it was made of limestone,

mud-brick, wood (for the original columns and superstructure) and

terracotta (for roof tiles and acroteria). In this century the Dorian states

of the Peloponnese and its religious centre at Olympia formed the heart

of the Greek world.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

43

THE GROWTH

OF THE

ATHENIAN STATE

1

A. ANDREWES

I. THE UNIFICATION OF ATTICA

The Iliad speaks of the Athenians as a single people. Homeric references

to them

are

indeed sparse

and

disputable:

it is

anomalous that

the

Athenian entry

in

the Catalogue (n. 546-56) names only Athens

itself,

whereas elsewhere

a

king's own city is followed by a string

of

further

place-names,

the

places where

his

warriors lived. Whatever

the

date

when this entry was composed

or

the reasons

for

its abnormality,

2

it

is further testimony

to

the feeling that the inhabitants

of

Attica were

a homogeneous people.with the single city

of

Athens as their centre.

They emerged from the Dark Age with no consciousness of any internal

racial difference to divide them, they spoke the same dialect, they were

organized in a unitary system of tribes, and in spite of substantial local

specialities they shared

a

common framework

of

rites and festivals.

Of

the process

by

which this was achieved, much necessarily remains

obscure.

The Mycenaean collapse left

a

remnant

on the

Acropolis, perhaps

literally beleaguered

in

the early stages while they still used the water

supply to which access had been elaborately engineered in the thirteenth

century.

3

In

eastern Attica the cemetery

at

Perati attests

a

relatively

prosperous twelfth-century community whose links were

not

with

western Attica

but

with other Mycenaean survivors

in the

Aegean

(CAH 11.2

3

, 666-7). This faded away,

in

circumstances

not

now

discoverable,

4

and the occupation of the Acropolis also came to an end.

Though the development through sub-Mycenaean

to

Protogeometric

shows that there was no sharp cultural break but a continuous process,

the Mycenaean way of life had finally ceased. We discover little

of

the

origins or organization of those who now lived in and around the city,

1

The Atthidographers arc cited by their serial number in Jacoby (FGrH): 324 F 34 is fragment

34

of

Androtion, no. 324

in

the series. Such references should

be

taken

to

include reference

to

Jacoby's commentary. Fragments of Solon are numbered according to the edition of M. L. West,

Iambi

tt

EiUgi Graeci

11

(Oxford, 1972).

2

A 48, 145—7 with

n.

72;

F 9,

3

j;

F

15, 219, esp.

n. 22.

4

H

35, nj-16.

360

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE UNIFICATION OF ATTICA 361

but it is clear that their lives were not very secure; in the rest of Attica

they avoided settlement near the sea or in isolated communities.

5

The Ionian migration (CAH 11.2

3

, ch. 38) is not only important

in

its own right, but carries implications which may clarify our picture of

Attica at the time when the movement began, in the eleventh century.

The links between Attica and Ionia are such that we are bound to accept

in the main the later Athenian claim to the leadership of

this

enterprise,

though this does not exclude that participation by other Greeks which

Herodotus attests

(1.

146.1), whether or not they passed through Attica

on their way. Evidence for an Ionian tribal system is weaker than that

for the Dorian tribes, and

in

East Greece there may have been less

uniformity, but the four old Attic tribes (below) turn up often enough

to constitute a genuine link (Hdt. v. 66.2,

69. i).

6

The Apatouria, which

for Herodotus

(1.

147.2) was the sign of

a

true Ionian community, was

not the only festival common to Athens and Ionia. The dialect which

we call Attic-Ionic must have been effectively established before the

migrants left Attica, whatever modifications it underwent subsequently

in either area.

If

the dialect was 'due

to

the fusion

of

West Greek

elements with a dialect of Mycenaean type' (CA.H

11.2

3

,

818), possible

conditions may have existed for this development in Attica by the end

of

the

twelfth century: all we need to posit is that people whose dialects

contained West Greek elements had infiltrated into

a

largely vacant

western Attica during the troubles in which the LH IIIB period ended.

7

The Ionian 'race', then, must have existed before' about 1050 B.C.,

even

if

we have

to

wait till Solon

(fr.

4a)

for a

clear expression

of

Athenian feeling about it. It seems now to be agreed that the settlements

made by the migrants in the east Aegean were new ventures; even

if

they

had

some earlier knowledge

of

that region, they were

not

reinforcing existing settlements. These courageous ventures, and still

more their general success, have rightly been claimed as a sign of Greek

vitality in the eleventh century;

8

but the reverse side of this should also

be noted, that they took off the most enterprising and adventurous of

the eleventh-century inhabitants,

a

serious loss even

if

the numbers in

each group of migrants were small.

The Athenians themselves saw these things more simply. They had

always been in Attica; and if it needed change to turn them into Ionians,

that was the work

of

Ion who came and settled among them and

imposed the four tribes named after his sons. Theseus by his

synoikismos

had brought them all together and made Athens their city, and so

it

remained. The basic distortion

is due to the

fact that they were

conscious of no break between the heroic period and their own times.

6

H

2j, 3)6.

* A

14,

I

II9-20;

F 9, JI.

'

H

35,

252-3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

362 43-

THE

GROWTH OF THE ATHENIAN STATE

They had no conception of a 'Dark Age' as we use the term; they

thought at most of early disturbances and movements after the Trojan

War, and even Thucydides, who makes much of these, believed that

Attica had not been affected (1. 2.5—6). What he has to say of Theseus

is reasonable enough, given the evidence available to him: he makes

the unification the political act of a powerful king, who dissolved the

separate governments of the various cities and set up a single prytaneum

and council-chamber in Athens, and this is what was celebrated in the

annual festival of the Synoikia

(11.

15.1—2).

The festival was a reality,

9

and we cannot neglect the implications

of its name and the story attached

to

it. The unification requires

a

political act

at a

specific time, or

at

least

a

specific conclusion to

a

piecemeal process. A unitary state the size of Attica is not normal in the

pattern of Greek settlement, even where there was no division of race:

Boeotians, Arcadians and Thessalians were conscious enough of racial

unity, but did not unite in the Attic manner. The three plains of Attica

are separated by barriers, easily surmounted but more marked than any

in the Boeotian plain or the plain of eastern Arcadia, and they could

well have supported three or more independent states, in a loose union

or none at

all.

The king of Athens would normally have been the most

influential ruler in Attica,

as

Thucydides presupposes, and that will have

been especially true for a period when so much

of

the population

huddled around his Acropolis. But Eleusis is eminently credible as

a

separate kingdom: apart from the legendary war with Erechtheus which

Thucydides cites, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter tells a story with

a

king of Eleusis and not even an allusion to Athens. The Marathonian

Tetrapolis, which in later times sent its own separate sacred embassies

to Delphi and Delos,

10

is another obvious candidate; and other sites,

which like these were inhabited when Protogeometric pottery was being

made, might once have stood on their own.

If there was ever a unified Mycenaean kingdom of Attica (cf. CAH

in. i

2

, ch. 16, p. 668: the Athenian entry in the Homeric Catalogue,

discussed above, cannot decide that question), it is hard to believe that

this survived the collapse, and we must look to the Dark Age for the

historical union of

Attica.

The literary evidence gives no clue to its date.

It would not be safe to deduce from the Hymn to Demeter that Eleusis

was still independent when it was composed, probably in the seventh

century;

11

an event of this magnitude, at a date not very long before

Cylon's remembered attempt to make himself tyrant, could hardly have

failed to leave some trace in Athenian tradition, whereas it can easily

be supposed that the traditional story of Demeter had retained its purely

9

F

6,

36-8.

l0

FGrH

328 F 75

with

commentary.

11

F 47,

j—II.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE ARISTOCRATIC STATE 363

Eleusinian colouring from an earlier age. The archaeological evidence

cannot date the event either, directly, but

in

ch. 16 (pp. 668—9)

^

ls

argued that the prosperity apparent in Attic graves

of

the early ninth

century resulted from the synoecism, and from the partial reclamation

of Attic land for cereal culture. We cannot see the political process by

which the isolated settlements in Attica were induced

to

join together

in a unified state, only the social and economic improvement it brought,

in comparison with

the

dark times after the Mycenaean collapse.

If

unification was completed around 900 the event could well have been

lost to exact memory, and in consequence have been attributed

to

the

Theseus of the heroic age, before the Trojan War.

We should think

of

unification

in

the terms

of

Thucydides 11. 15.

There was no large transfer

of

population, as synoecism would mean

to later times, but

a

centralization

of

government. The noble families

no doubt mostly found themselves

a

residence in or near the city, but

they retained their roots elsewhere or put down such roots later. The

momentum of this first advance was not maintained, either in prosperity

or

in

reclamation

of

the land, and much remained

to

be done later.

II.

THE ARISTOCRATIC STATE

The meagre stories that were told of the kings of Athens need not long

detain us. Names and scenes on Attic pottery give us some idea of what

was already current before the end

of

the sixth century, and parts

of

the 'history' were well enough developed before the time of Herodotus

(1.

147.2,

173.3,

vin

- 4

2

> etc.). But the widespread opinion is probably

right, that stemma and chronology were not systematized till Hellanicus,

late in the fifth century.

12

Among his voluminous works was the first

Attbis,

a

specialized history

of

Athens down

to

his own time.

It

was,

surprisingly, some fifty years before his example was followed

by a

native Athenian, Cleidemus; the prominent politician Androtion wrote

his more often cited Attbis

in

exile

in

Megara, probably

in

the 340s;

the last, longest and greatest in this genre was the work of Philochorus,

'the first scholar among the Atthidographers', unfinished

at

the time

of his death, probably

in

263/2.

13

We know these works only from

quotations, mostly by commentators on Aristophanes and the orators,

and

the

commentators' special interests

-

topical allusions

in

their

authors, or matters of Athenian cults

or

practices which would not be

familiar

to

their readers

—

ensure that our fragments are

an

unrepre-

sentative selection. Study of fragments with book-numbers shows that

they devoted

far

more space

to

their own times than

to

early history;

12

A

1

j,

n

5

6;

FGrH on 323a F 23.

13

F

15;

cf.

FCrH,

introductions

to

individual Atthidographers.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

364 43-

THE

GROWTH OF THE ATHENIAN STATE

in the extreme case

of

Philochorus, the books dealing with his own

lifetime were nearly two thirds of the whole, but they are represented

by only

a

minute fraction

of

the many quotations

we

have.

The

suspicion that their contemporary political interests distorted their view

of early Athens, coupled with scepticism about the possibility of their

having

any

genuine information,

has led to

some excessively

low

estimates

of

their value;

14

but they knew things that we do not, and

we must judge each case on its merits as best we can.

The Atthidographers faced considerable difficulties

in

constructing

an early history for Athens. The scattered stories were not connected

among themselves or with the general stock of Greek legend, and there

were

not

names enough

to

furnish

a

king-list

of

adequate length.

Cecrops and Erechtheus, primitive divinities not perfectly humanized,

gave the list

a

start; but Ion, though he was the eponym of the whole

race and the tribes were named after his sons, was not (or somehow

could not be) brought into the royal genealogy, and came in as a military

leader (so already Hdt. vin. 44.2) for Erechtheus' war against Eleusis.

Theseus' sons

had

somehow

to be

dispossessed

to

make room

for

Homer's commander of the Athenians, the shadowy Menestheus, and

his father Peteos. The end-product was a d_ynasty of fifteen kings, from

Cecrops to Thymoetes, followed by a second dynasty from Pylus headed

by Melanthus and Codrus (Hdt. v. 65.3). After Codrus, reputedly father

to

the

founders

of

many Ionian cities, either

his

son Medon

or his

grandson Acastus surrendered the kiftgship in exchange for the office

of' archon for life'; after eleven more of these, there begins a series of

seven archons holding office for exactly ten years each; then the list of

annual archons start with Creon, in the year

682/1.

18

The name Acastus

is of interest, in that the later archons' oath .referred

to

him {Ath. Pol.

3.3); the rest of the construction can be neglected. In effect we cannot

describe

or

date the stages of the process by which the monarchy was

dismantled.

The creation of an alternative executive officer, coexisting with the

king

or

replacing him, seems

to be a

regular development

in

Greek

constitutions; even at Sparta, v^here hereditary kingship survived, most

of the king's functions, priestly, judicial

and

political, were

put in

commission among the aristocracy. At Athens we find a group entitled

'the nine archons'. One

of

them still had

the

official title fiaoiXevs,

though

by now he had

become

an

annual official;

the

continuity

suggests that there had been no traumatic revolution. He performed

many

of

the older rituals,

and

later continued

to

preside over

the

Aeropagus when

it

sat as a murder court. But the chief executive,

by

the time the historical record begins, was 'the' archon, who gave his

14

E.g. F

9,

12-15.

1S

A

14, 11 783-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008