Boardman J., Hammond N.G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DELPHI

315

Mt Oeta but had spread to Euboea and the islands, to Epirus,

southwards to Parnassus (and thence even to Asine in the Argolid;

above

p.

309). Delphi figures largely in their story, so too does Heracles,

as conqueror, master or patron, so their appearance in the war does not

surprise, but who they were or where they were around 600 we cannot

tell,

a remnant of something surviving near Delphi, interested in Delphi,

allied with Cirrha, and hence on the losing side.

49

Also on the losing

side,

by implication, were the Cypselids in Corinth and, still more

distantly,

Argos.

Here later sources help more significantly, for Cypselus,

it was said, gave one of his sons the name Pylades, scarcely to be

dissociated from the heroic Pylades, Orestes' friend and member of

the royal house of Cirrha, founder, on one account, of the Pylaean

Amphictiony. Again, in yet another tale, Acrisius, king of Argos, after

helping the Delphians in a war against their neighbours, himself

founded an amphictiony at Delphi, later to absorb that of Thermopylae.

Would it be rash to see here attempts by Cirrha and her southern allies

to claim a voice in Thessaly's own province? Or to add the intrusion

of Corinthian Sisyphus into the legends of Central Greece, or even the

possible intervention of the Cypselids in Euboea?

The world of propaganda is a topsy-turvy world, and here we have

little but propaganda, Greek propaganda at that, among the most

ingenious and contorted known to man (Greeks rarely denied an

opponent's story

—

they preferred to take it over and stand it on its

head).

But, to repeat, the main theme is clear, a struggle between Cirrha

and the Amphictiony for possession of Delphi, each with its friends.

Behind the Amphictiony, Thessaly, left out of the Delphic circle after

670,

may merely have seen a chance to reinstate

herself,

but she too,

like Athens and Sicyon, may have had some special grievance, may have

felt some direct threat from an over-ambitious oracle. If

so,

the overall

pattern is clear, whatever the doubts in detail. The successes of the

seventh century had put Apollo's authority beyond question, but

perhaps they had also turned his head a little, had prompted him to

interfere, to insult, to challenge those who not only resented but had

the power to make their resentment felt. Turned his head? Prompted

him} No, Apollo himself was above error - it must be his priests who

were to blame; new guidance was needed at the sanctuary to see that

the god's true will was done.

And so indeed it was. In the developed Amphictiony each tribe had

two seats on the council. This would have been a suitable moment for

Athens to be granted the second 'Ionian' place (less suitable, given

Cleisthenes' background, for Sicyon to become the second 'Dorian').

Athens certainly benefited in other ways, more specifically Solon, who

49

Aeschin. m. 107; Anton. Lib. iv; E

IJO,

no. 448; cf. E 83.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

316

41.

CENTRAL GREECE AND THESSALV

had Delphic patronage

for his

reforms

and

Delphic support

in his

struggle with Megara

for

possession

of

Salamis,

and the

family

of

Alcmaeon

who

owed

to

Delphi their introduction

to the

wealth

of

Lydia,

who

rebuilt Apollo's temple after

its

destruction

by

fire

in 548

and found

a

grateful ally in the Pythia

for

their political enterprises later

in

the

century. Meanwhile,

in the

5

70s,

their then leader, Megacles,

son

of Alcmaeon,

had

been honoured with

the

hand

of the

daughter

of

his father's comrade-in-arms, Cleisthenes, whose continued links with

Delphi have already been mentioned.

One

other more general effect

of

his influence

may be

detected. Delphi before

600 was by no

means

an

exclusively Dorian sanctuary

but

there

is a

strong Dorian flavour

to it;

after 600, with the advent of Ionian Athens and anti-Dorian Cleisthenes,

one senses

a

shift

of

emphasis

-

Ionians from Naxos, Phocaea, Siphnos

come as enquirers

or

generous dedicators, and fine objects of East Greek

workmanship begin

to

appear.

50

More significantly,

it

is only when Sparta, towards

the

middle

of

the

century, gives

up her

traditional policy

of

aggressive Dorianism

and

begins

to

advertise herself

as the

'Achaean' leader

of a

voluntary

Peloponnesian alliance that

she

reappears

on

Delphi's visiting-list.

Indeed

it

would appear that Delphi itself had

a

hand

in

persuading

her

to make

the

change,

for it was on

oracular advice that

the

Spartans

decided

to

recover the bones of Achaean Orestes, symbol of pre-Dorian

hegemony

in the

Peloponnese,

but of

hegemony

to be

achieved

by

alliance

not by

annexation.

51

This

is not to

say that Delphi became anti-Dorian. Spartans, after all,

were still, however mutedly, Dorian. So too were the Corinthians who,

after

the

fall

of

the Cypselids

in

582, became allies

of

Sparta, honoured

Solonian Athens

at the

Isthmian Games

and

whom

the

Delphians,

graciously

if

ungratefully, allowed

to

erase

the

name

of

Cypselus from

his treasury. Indeed

the

change, such

as it

was,

may

well have been

a

result

of

an accident of politics rather than

of

any consciousness

of

race.

Such consciousness existed among Greeks,

but few

things

are

harder

to measure than

its

power

to

move rather than merely

to

irritate.

Certainly

it was

political accident (though perhaps with some slight

racial overtones) which produced

the one

serious loss

to the

oracle's

clientele after about 560. In Athens, Solon's 'party' split and Pisistratus,

leader

of

the break-away ' left-wing', became tyrant. There was no room

at Delphi both

for

Pisistratus

and for the

remaining Solonians,

now

led

by the

Alcmaeonids,

and so,

either

by

inclination

or

invitation,

Pisistratus resigned

the

Delphic whip. Causes

or

effects?-a marriage

with

an

Argive

who had

previously been

the

wife

of a

Cypselid

and

an association with

the

predominantly Ionian Apollo

of

Delos,

an

50

E

77

.

61

E

159,

ch. 7.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

DELPHI

317

association which he shared with his friend Lygdamis of Naxos and with

Lygdamis' friend, Polycrates

of

Samos.

In

the tension after Pisistratus'

death

his

sons allowed

one of

their sons

to

offer

an

altar

to

Pythian

Apollo

as

they offered

an

archonship

to an

Alcmaeonid,

but the

placatory gesture,

if

such

it

was,

had no

more success than

the

similar

and contemporary overture made

by

Polycrates. 'Shall

I

call

my new

festival Pythian or Delian?' asked Polycrates.' It's all the same

for

you',

replied

the

Pythia,

and

Polycrates soon died.

The

Pisistratids

did not

survive in power much longer. Alcmaeonid intrigue, Delphic diplomacy

and

a

Spartan army liberated Athens.

In 510

(Lygdamis

too had dis-

appeared)

it

must have seemed

a

dangerous thing

to

displease Apollo.

To flatter

him, as the

Alcmaeonids

did by a

lavish rebuilding

of his

temple, burnt down, false rumour had

it

by the Pisistratids; to obey him,

as

the

Spartans

did; to

reward

him as the

Athenians

did

with their

treasury

at

Delphi; that was

the

prudent course.

But

to the

north there was

no

such tidiness

or

harmony under

the

Amphictionic umbrella. Some

of the

confusion

we

have already

explored,

and

their reasons

for it,

weakness

of

evidence, dissensions

within as well as between the main units, Thessaly, Boeotia, Phocis.

The

simplest story would

be

that

the

Thessalians (collectively

so far as we

know) extended their influence southwards

at the

time

of the

Sacred

War

so

effectively that they were able

to

take control

of

Phocis, either

through puppet tyrants or by direct Thessalian government, maintaining

at

the

same time their hold

on

Delphi through their majority

on the

Amphictionic council

and

their friendship with Sicyon

—

a Scopad

of

Crannon

was one of the

contestants

for the

hand

of

Cleisthenes'

daughter

in

the 570s, albeit unsuccessful; that they then tried to expand

further into south-west Boeotia

but

were pushed back with

the

loss,

it was said,

of

4,000

men

from Ceressus

in the

territory

of

Thespiae,

Pausanias implies by the Thespians alone, Plutarch says the' Boeotians',

a reverse which was followed, around 500,

by a

revolt

of

Phocis

and

the rout

of

a

retaliatory expedition

in at

least two engagements, one

of

the Thessalian foot below Parnassus,

the

other

of

their famous cavalry

at Hyampolis

to the

north-east.

52

The

dedications received

by

Delphi

to celebrate

the

Phocian success show that

yet

again

it had

chosen

the

profitable course, a choice virtually imposed by geography but perhaps

already encouraged by Thessalian friendship with the Athenian tyrants,

maintained

to the end of

the tyranny

and

even beyond when fugitive

Hippias

was

invited

to

settle

at

Iolcus.

The

simplest story

-

and

probably

in

outline true. But there are awkwardnesses. Thebes had also

helped Pisistratus

at the

outset

and his son,

Hipparchus, dedicated

at

the Ptoion,

53

as, to confuse things further, did an Alcmaeonid, yet some

" Above, pp. 304-5.

M

BCH

40

(1920)

2

37

ff.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3 I 8

41.

CENTRAL GREECE AND THESSALY

Boeotians, the Tanagraeans, felt able

to

consult Delphi before joining

the Megarians in colonizing Heraclea in the Black Sea about the middle

of the century and the Thebans themselves sought Delphic advice

in

their troubles around

505.

54

We must besides look for contexts for the

alliance between Thebes, the Locrians and the Phocians advertised by

the author

of the

Shield,

and for the

building across

the

pass

at

Thermopylae of a wall, the so-called 'Phocian' wall which lay in ruins

when the Greek force arrived there

in

480 (Hdt. vn. 176.3-4). These

snags can be circumvented but not without leaving the uneasy feeling

that the simplest story is not always the best.

Meanwhile, however,

a

new question was beginning

to

pose itself

for Greek politicians

—

the cloud

in

the east.

A

matter

of

interest but

of little concern when the Persians first appeared

on

the Ionian coast

about 540, more pressing with their advance into Europe

in

514 and

then overwhelming as invasion came nearer. For states and for factions

within the states this was not only

a

new problem,

it

was

a

new kind

of problem, here reinforcing, there cutting across

old

friendships

or

enmities. For Delphi

it

was even more acute and even more immediate

than for most. Her close ties with Gyges of Lydia may or may not have

survived her switch

of

interest around 675.

At

least we hear nothing

of contacts with Gyges' successors, Ardys and Sadyattes,

or

with

the

next king Alyattes until shortly before 600 when he is undergoing some

change

of

heart

in the

course

of

war with Miletus

(the

figure

of

Periander hovers intriguingly but appropriately around the edges of the

story which brings Delphic advice

to

Alyattes and grateful reward:

Hdt. 1. 19-22). But, renewed or continuing, the Lydian connexion was

not broken

by the

events

of

the 590s.

It

was through Delphi that

Alcmaeon, one of the ' liberators', made highly profitable contact with

the Lydians and it was in Alyattes' son, Croesus, that Apollo found one

of his most ardent admirers. The story of Croesus' association with the

oracle needs no rehearsal; of his oracular' jeux sans frontieres', his lavish

gifts

to

victorious Delphi, housed, appropriately,

in the

Corinthian

(once Cypselid) Treasury, alliance with Sparta, surely with Delphi's

support, and then the disastrous advice to cross the Halys and destroy

an empire. After Croesus' defeat at the hands of Cyrus and the capture

of his capital Sardis c. 546 'advice

to

cross' became

a

'forecast

of

the

result of crossing' regrettably misunderstood and indeed the whole tale

of Croesus as we have it in Herodotus is cast as an apologia, but modern

scholars have exaggerated

the

extent

of

contamination

—

Croesus'

approach to the oracle shows genuine eastern traits and, above all, the

richness

of

his gifts alone is

a

measure

of

Delphi's involvement.

55

For

her, then,

the

Persian victory was

not an

alien affair. The Milesians

54

E 150, no. 81. "

Hdt

- 1.

46-9'icf-

E

"5-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

DELPHI

319

somehow contrived to make their peace with Cyrus (what were their

relations with Delphi at the time?), but other Ionians suffered, among

them the Phocaeans who had consulted the oracle some years before

about a colony in the west. At home one close friend, Sparta, indulged

in a foolish little gesture of protest, but, nearer the heart of things,

Croesus himself had survived to find a place at the Persian court, and,

it was said, had forgiven Apollo for any inconvenience he had caused.

It did not take Delphi long to decide which friend to follow. Faced with

the approach of the Persians the people of Cnidus asked for advice in

the construction of a defensive canal - 'Desist' replied the Pythia, 'God

would have made Cnidus an island, if he had wished it so' (Hdt.

1.

174).

The theme was set for the final surrender, the theme, but not the details

of its development. For to what we may call normal domestic

complications, already noted, this new element was added. In Thessaly

the Aleuadae medized, other noble houses did not;

56

in Athens the

tyrants showed signs of medizing, but so did their enemies the

Alcmaeonids; in Sparta King Cleomenes finally chose the patriotic

course but his association with the oracle was murky

—

and in any case,

when the Persians finally came he was dead and his fellow-king was at

Xerxes' side; the Aeginetans, whom Delphi tried to save from an

Athenian attack c. 504, submitted to Darius before 490 but fought

bravely in 480; in Boeotia the Thebans at first fought feebly, then with

most other cities collaborated with enthusiasm while Plataea and

Thespiae alone stayed loyal; so too did their neighbours in Phocis

—

but

only, Herodotus remarks (vin. 30), because the Thessalians were on the

other side. The full story of the great war will be told in a later volume.

For us it is enough to note that so far as was possible in all this confusion

Delphi counselled caution or submission. There was no formal

presentation to the Great King of a handful of Delphic Ga or a cup of

Castalian water, but the simple fact is that Apollo, together in the end

with most of his amphictiony, medized.

It is no accident that thereafter Delphi ceased to be an active power

in Greek politics. Still a useful moral support as she was for Sparta in

the Peloponnesian War, still revered by private citizens as she was from

Socrates to Plutarch, she was no longer a force, as she had been, that

could make governments, promote alliances, initiate wars. It is hard not

to see the glorification of the sanctuary in the years after 489 as little

more than an embarrassing farce designed by the victorious Greeks to

cover up the fact that their god had failed them.

Four great moments of

decision.

The first hardly a decision at all - in

the Lelantine War Delphi had been adopted by the winning side; the

second, in the political revolution of the seventh century, a triumph;

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

32O 4

1

- CENTRAL GREECE AND THESSALY

the third an error, from which she was saved by the calculated piety

of the victors in the Sacred War; but the fourth an error from which

she could not be saved. That a divinely-inspired oracle should produce

accurate predictions of the future over a period of two hundred years

and more is a belief that would tax the credulity of all but the most

devout; that human priests should arrive at one original and correct

answer in four would seem to be just about the right score.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

42

THE PELOPONNESE

N. G. L.

HAMMOND

I. SOME PROBLEMS OF CHRONOLOGY

When the Pleiades, daughters of

Atlas,

rise, begin your harvesting; and when

they are about to set, begin your ploughing. Forty days and forty nights they

are in hiding, but as the year revolves they appear again, when your sickle is

first being sharpened. (Hesiod,

Works and Days

383—7)

Every shepherd and every farmer needs

to

know the details

of

the

seasons and the tally of the years. Although literacy lapsed in the Dark

Age,

men

remained numerate

and

counted

the

lunar months, each

within

his own

small group. When these groups coalesced into

a

community or state, or when they engaged in a joint activity, a common

standard

of

time-reckoning was needed. Each state created

its own

calendar, naming the months by

a

number

or a

deity

or a

festival and

beginning

the

year wherever

it

pleased; occasionally

a

month-name,

such as the Carnean month in honour of Apollo Carneus, was common

to several states, but usually each state drew

its

names from

its

own

sources

and

sometimes even

had

Mycenaean names.

As

trade

and

intercourse developed, the need to label the years within

a

community

was met by naming each year after

an

'eponymous' official, whether

priest or magistrate, and keeping a list of the names, e.g. that of Elatus

as the first eponymous ephor

of

Sparta

in

754

B.C.

(Plut. Lye. 7).

1

A

system which several states could share was devised at Olympia, where

the festival was held once every four years and

a

sacred truce

for its

duration was observed

by

the participating states. The festival years

were numbered consecutively

and

named after each winner

of the

foot-race

{stadiori),

the first Olympiad in 776

B.C.

being that of Coroebus

of Elis (Paus. vm. 26.4). Where

an

official held office

for

life,

as the

priestess

of

Hera

at

Argos did,

the

years

of

his

or her

tenure were

numbered.

As these lists were compiled

not for

academic purposes

but for

practical use,

it

seems obvious that they were used to date actions and

1

The year B.C.

is

supplied

by

Apollodorus, FGrH 244 F 335a.

5

21

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

322

42.

THE PELOPONNESE

19

<Q

HI @

Hl

KEY

\ Karpophor

i o.

. %) Coroneol

Sphactena J I

LMethone

aJi_(5

Asine

MESSENIAN

GULF

Sparta<>

m

—\

c=

Co

\

\

x

}

C.Ta

\oTherapne

dyAmyclae

L A C?0

N

1

\ LACONIAN

K GULF

I

enarum

Land over

1,000

metres

I

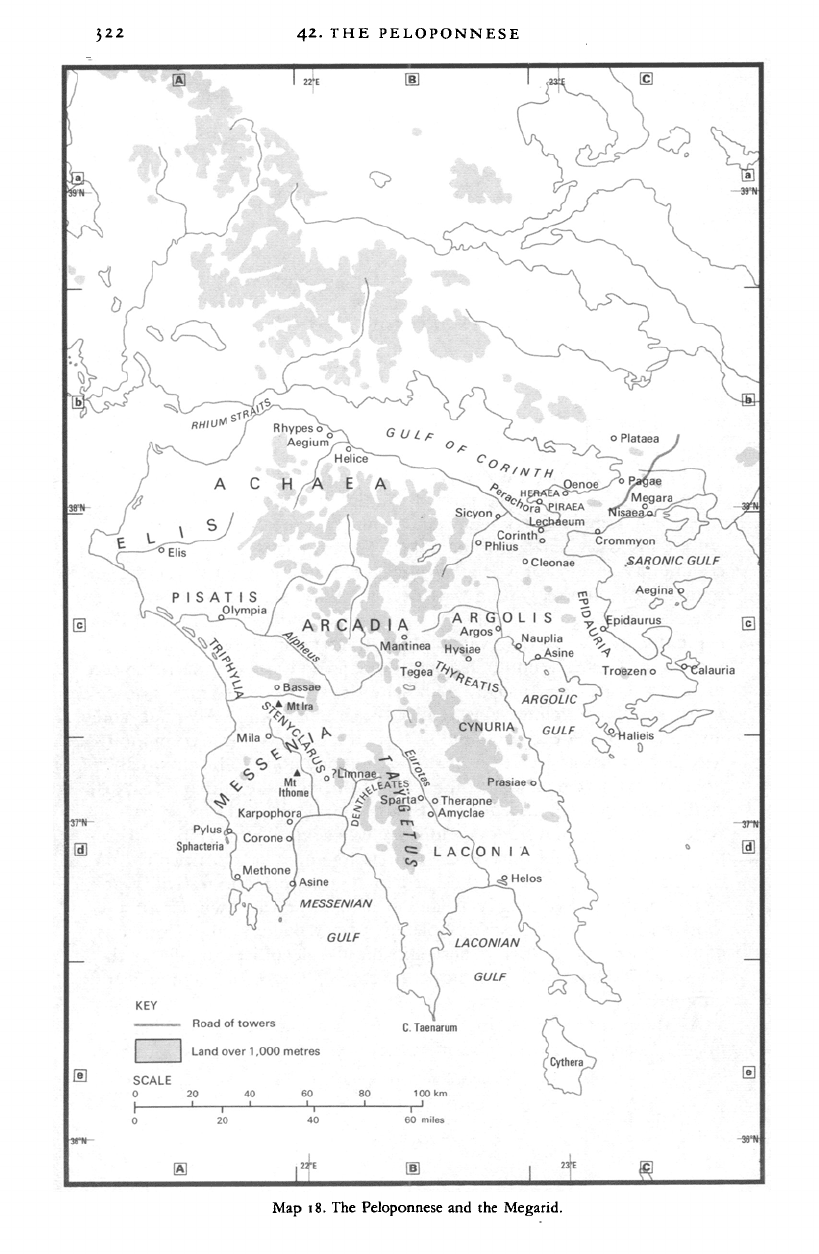

Map 18. The Peloponnese and the Megarid.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOME PROBLEMS OF CHRONOLOGY 323

events

at

the time; and

it is

probable that such events were noted

at

the appropriate place in the list. To give an example from Megara, where

a memorial

to

one Orsippus was set up on the order

of

Delphi and an

epitaph

was

composed

for it,

perhaps

by

Simonides,

we

learn that

Orsippus was

the

first

to

win the station running naked; and the list

of victors

in

that event having survived,

we can

date

his

victory

to

720 B.C., some two centuries before the composition

of

the epitaph.

2

No doubt he had been recorded on the list at Olympia as the first naked

runner.

Or

we may note

an

entry

in the

list

of

priestesses

of

Hera

at

Argos, which Hellanicus published late

in

the fifth century: 'Theocles

from Chalcis together with Chalcidians

and

Naxians founded

a

city

in Sicily',

3

namely Naxus c. 734.

The

probability

is

that Hellanicus

published what

he

found

in

the list,

not

that

he

added this particular

piece of information

himself.

In any case, once such lists were kept and

years were labelled, events such

as the

foundation

of a

colony were

recorded

far

more accurately

in

relation

to

them than

to

any form

of

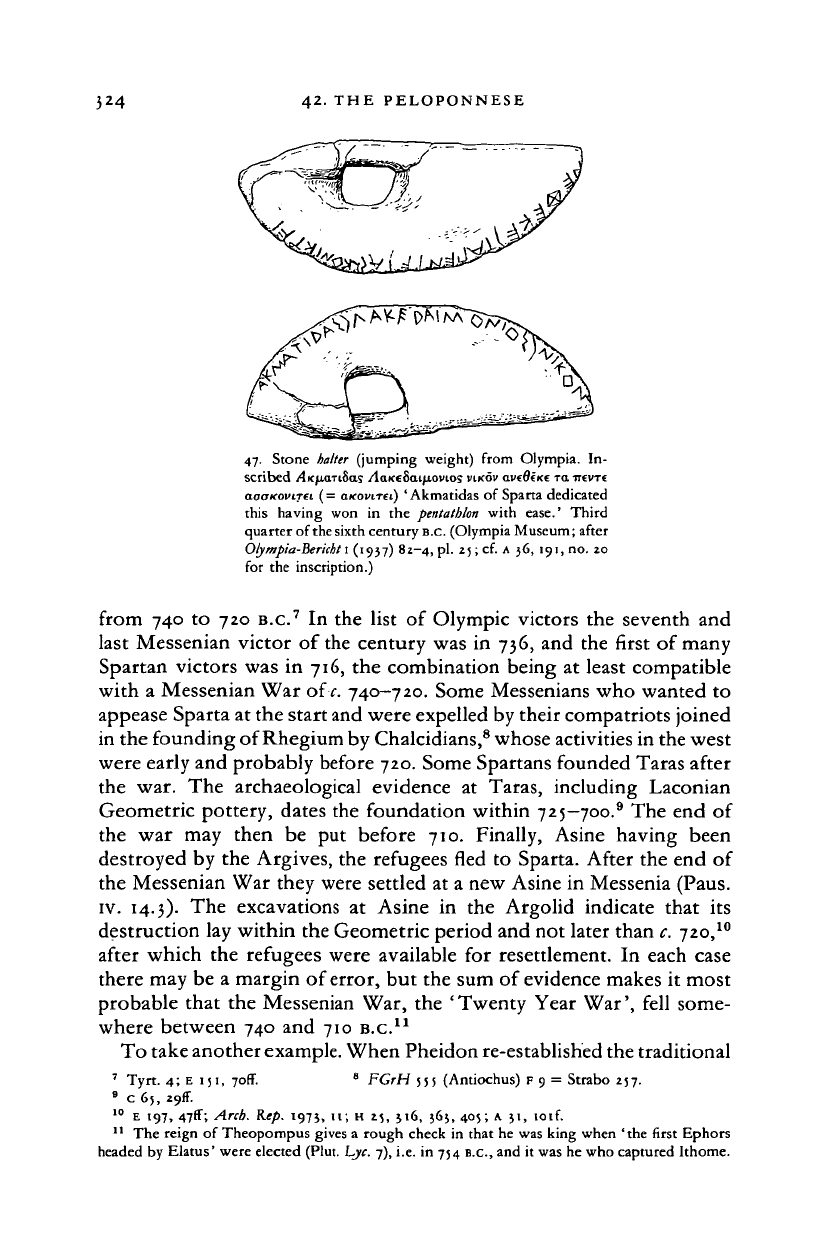

genealogical reckoning. Occasionally

an

object

of

antiquarian interest

supplied

a

dating. Thus

a

bronze quoit

or

discus

at

Olympia had

an

inscription running round

it

(as

on a

jumper's weight (fig. 47),

or on

the shoulder of a vase

c.

730 B.C.),

4

which referred

to

the truce

for

the

Olympic Games. Aristotle saw this quoit and read there the names

of

Iphitus, the reputed founder

of

the reconstituted games

in

776, and of

Lycurgus whom he equated with the reputed author

of

the

eunomia

at

Sparta. He inferred from the inscription that they had collaborated

in

arranging the terms of the truce for the festival.

5

It

is obvious that the

truce was worthless unless

it

was validated by an official representative

of each participating state, e.g.

in

Sparta's case

by a

King

or

Geron.

Aristotle may

in

fact have been right

in

identifying this Lycurgus,

a

Geron well over sixty, with the famous legislator.

6

If

he read the name

of Iphitus correctly,

it

is the earliest inscription

of

which we know by

report and helps

to

date the adoption

of

the alphabet.

The dating

of

the First Messenian

War

may

be

determined with

probability

in

the following way. Tyrtaeus, who flourished about the

middle

of

the seventh century, said that

'our

fathers' fathers fought

for nineteen years', and that in the twentieth year the enemy fled from

the high mountains

of

Ithome.

If we

take seventy years

as a

very

approximate span

for

the two generations (as one might

in

referring

now to World War I), the First Messenian War ran very approximately

2

E. L.

Hicks and

G.

F. Hill, CHI no. 1 with references.

3

FGrH 4 F 82.

4

Illustrated

in

'Iaropia

TOU

'EXXT]VIKOV

"Edvovs

B

198 and 483.

s

Plut. Lye. 1

and

23; Paus.

v.

4.5

and

20.1; Ath. xiv. 63;F.

6

If

Lycurgus carried

the

reform

in

his prime and acted

at

Olympia

as a

'geron' over sixty,

Thucydides' date

of c

810 B.C.

is

compatible with that

of

Aristotle.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3

2

4

42-

THE

PELOPONNESE

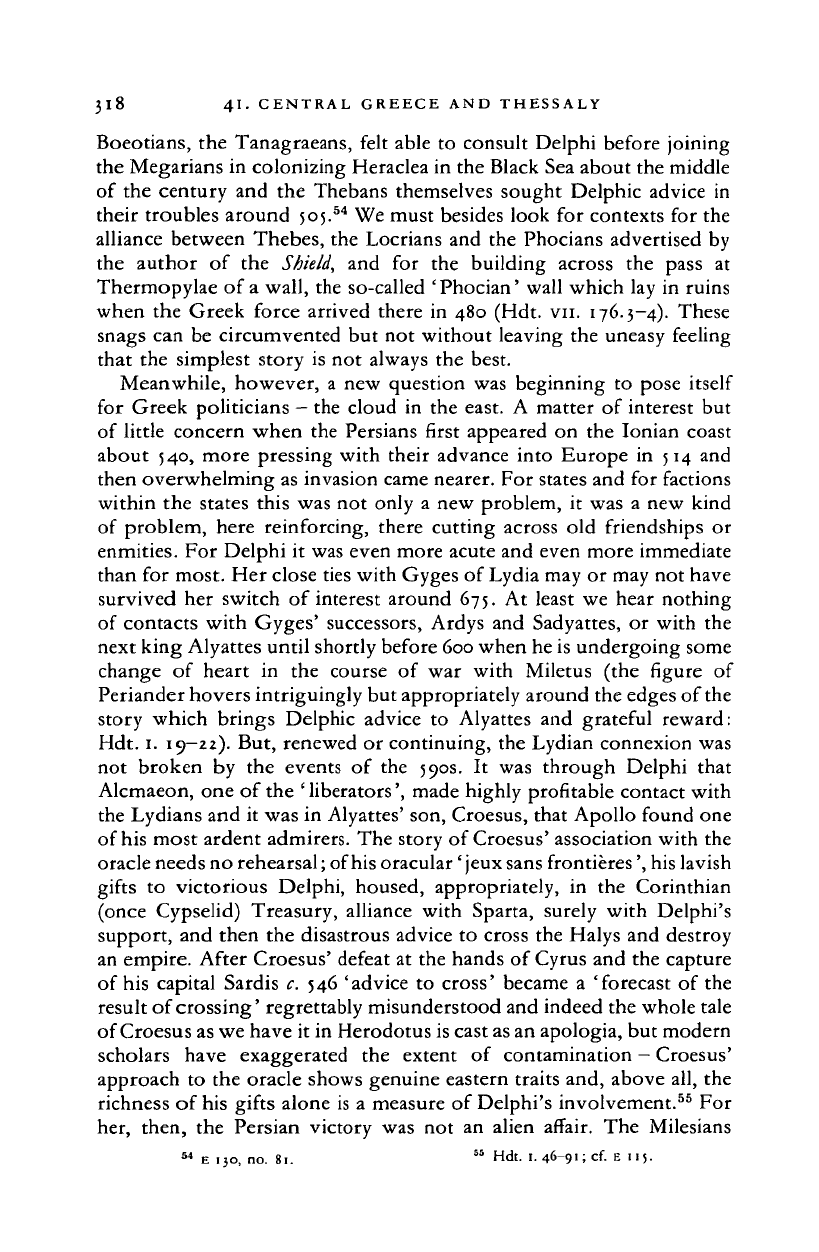

47.

Stone

halter

(jumping weight) from Olympia.

In-

scribed ^4/c/xaTiSa?

AaKeSaifiovtos

VIKOV

a»£0e/c£

ra

TTtvre

aooKovLjei

(=

atcovirei)

'Akmatidas

of

Sparta dedicated

this having

won in the

pentathlon

with ease.' Third

quarter of the sixth century

B.C.

(Olympia Museum; after

O/ympra-Bericbti(iy$j)

82—4,

pi.

2j;cf.

A

36,

191,

no.

20

for

the

inscription.)

from

740 to 720

B.C.

7

In the

list

of

Olympic victors

the

seventh

and

last Messenian victor

of

the century

was in

736,

and the

first

of

many

Spartan victors

was in 716, the

combination being

at

least compatible

with

a

Messenian

War ofr.

740-720. Some Messenians

who

wanted

to

appease Sparta

at

the start and were expelled by their compatriots joined

in

the

founding of Rhegium by Chalcidians,

8

whose activities

in

the west

were early

and

probably before 720. Some Spartans founded Taras after

the

war. The

archaeological evidence

at

Taras, including Laconian

Geometric pottery, dates

the

foundation within 725-700.

9

The end of

the

war may

then

be put

before

710.

Finally, Asine having been

destroyed

by the

Argives,

the

refugees fled

to

Sparta. After

the end of

the Messenian

War

they were settled

at a new

Asine

in

Messenia (Paus.

iv. 14.3).

The

excavations

at

Asine

in the

Argolid indicate that

its

destruction

lay

within

the

Geometric period

and not

later than

c.

720,

10

after which

the

refugees were available

for

resettlement.

In

each case

there

may be a

margin

of

error,

but the sum of

evidence makes

it

most

probable that

the

Messenian

War, the

' Twenty Year

War',

fell some-

where between

740 and 710

B.C.

11

To take another

example.

When Pheidon re-established the traditional

7

Tyrt.

4;

E

1

JI,

7off.

8

FGrH 555 (Antiochus)

F 9 =

Strabo

257.

9

c 65, 2

9

ff.

10

E 197, 47ff;

Arch.

Rep.

1973,

n; H 25, 316,

363, 405;

A

31, loif.

11

The

reign

of

Theopompus gives

a

rough check

in

that

he was

king when

'the

first Ephors

headed

by

Elatus' were elected (Plut. Vyc. 7),

i.e. in 754

B.C.,

and it

was

he who

captured Ithome.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008