Boardman J., Hammond N.G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MACEDONIA

285

Macedones spoke Illyrian or Thracian. Indeed, it has become clear from

the inscribed stelai at Vergina which Andronikos has found recently,

that the fathers of Philip's Macedonians had entirely Greek names, and

we may deduce that their parents spoke Greek at the beginning of the

fourth century. What then of earlier times ? Hesiod certainly thought

them to be Greek-speaking; otherwise he would not have made Magnes

and Macedon into cousins of Dorus, Xouthus and Aeolus, who were

the eponymous ancestors of the three main forms of the Greek language

(Dorian, Ionian and Aeolian). Hellanicus, writing late in the fifth

century, made Macedon a son of Aeolus; he would not have done so

unless he had supposed the Macedones to be speakers of some form

of Aeolic Greek. As the twin people, the Magnetes, did speak an Aeolic

dialect (this we know from inscriptions), there is no good reason to

deny that the Macedones spoke an Aeolic dialect, retarded indeed and

broad, because the Macedones, like the Vlachs of Vlakholivadhi, had

been a self-sufficient community on the foothills of Olympus for many

centuries.

43

If we are correct in our conclusions, the Greek speech of the tribes

in Epirus and in Macedonia west of the Axius should not be ascribed

to the influence of the Greek colonies on their coasts. Nowhere in fact

did Greek colonies convert the peoples of a large hinterland to Greek

speech; for the differences in outlook and economy between colonists

and natives were too great. Equally so in Epirus and Macedonia. For

example, Eretria planted a colony at Methone before 700 B.C., but it

had no effect whatsoever on the culture of the people who buried their

dead at Vergina, only some fifteen miles away as the crow flies. So too

the Greek colonies in Chalcidice had no influence on the Bottiaei during

our period, as far as the archaeological evidence goes. If these tribes

of the hinterland spoke Greek, it was because they had done so before

the Dark Age. What we have seen in this chapter is the consolidation

of the Greek-speaking tribes in the north, which enabled them to fulfil

their future role of defending the frontiers of

a

city-state civilization and

later of leading that civilization into wider areas.

43

See CAH m.i

2

, %^S for a different view. There is a summary of the problem in

E

34,11

46ff.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

41

CENTRAL GREECE AND THESSALY

W.

G. G.

FORREST

For the period before about 700

B.C.

the chief tools

of

the historian

of

Central Greece must be the spade

or

the map, though a few strokes

of

ancient pens add a welcome touch of political definition to some events

of the second half

of

the eighth century

in

stories

of

colonization and

especially of the Lelantine War (CA.H

in.

i

2

,

pp.

,760—3,

and here

ch.

39^)

which involved

not

only the cities

of

Euboea,

but

southern Thessaly,

Megara, Delphi and other states besides.

More importantly, it was about the same time that Boeotia produced

in the poet Hesiod our only contemporary literary evidence for the social

and political atmosphere

of

Late Geometric Greece.

1

1.

HESIOD

Hesiod's life spanned, roughly, the second half

of

the eighth century,

spilling over, perhaps, into the seventh. His father,

a

trader

of

Aeolic

Cyme, had turned his back on the dangers of the sea to settle on

a

farm

at Ascra

on the

north-west slopes

of

Mt Helicon,

a

miserable village

according

to

the poet, awful

in

winter and worse

in

summer, but

not

perhaps quite so bad as Hesiod's gloom would have us think

-

at least

it was famed

in

antiquity

for

its beetroot (Ath. 4D). There Hesiod and

his brother Perses were born and there, after their father's death, they

fell

to

quarelling over the estate,

a

quarrel which prompted that hard

picture

of

the farmer's year and stern sermon on justice, the Works

and

Days, this around 700 B.C. Somewhat earlier

he

composed

his

other

surviving work, the

Theogony,

an account of the genealogies of the gods

of Greece attached

to

the myth

of

the succession

of

Cronus

to

Uranus

and

of

Zeus to Cronus as Lord of the Gods, the backbone of the poem.

Of other works we have only fragments.

Hesiod, like Homer, lived

in the

time

of

transition from oral

to

written composition. Indeed

it

seems likely that each was the first,

or

among

the

first,

to

commit

to

manuscript his own version

of a

long

oral tradition.

We can

assess their merits

as

artists

but not

with

any

1

A

71;

A

72;

E 144.

286

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

HESIOD

287

precision their own contribution in terms of content or the stages of

growth in what they inherited.

For the historian two questions pose themselves. First that of the

inspiration of

the

Theogony.

Primitive accounts of the origin of

the

world

and the gods abound from Polynesia to Persia, from Germany to Japan,

but the closeness of parallels with near-Eastern versions, especially with

the Babylonian Enuma EM, show that the Greek was no spontaneous

local creation. But when imported? Two periods of oriental contact

suggest themselves, the Minoan-Mycenaean and that of the re-opening

of eastern links with the founding of Al Mina, a little before 800

B.C.

For the former it is argued that time would be needed for the complete

absorption of eastern elements, for the latter that it offers more positive

association of the east with Greece, especially with Central Greece, and

that seventy-five years or so would be time enough. But even in this

second context further choice is offered. That the story came via the

Hittite empire to Phrygia and thence across the Aegean is unlikely if

not impossible. But a route from Al Mina through Crete to Delphi (both

figure in the

Theogony)

is as attractive as the more direct one to Euboea

and thence Boeotia; either is

a

trifle more attractive than the assumption

of a Mycenaean survival. If so, we have a powerful religious element

to add to a possible political and a striking artistic one in the sum of

Greece's debt to the east.

2

Herodotus (11.

5 3)

may not have been too

far from the truth when he said that Hesiod and Homer were the first

to set down a 'theogony' for the Greeks and give the gods their

appropriate functions. He need only have added a note on their sources.

Secondly we have to ask about the society in which and for which

Hesiod wrote. Here the difference of his subject-matter from that of

Homer justifies the assumption that what he says still applies in his own

day even if much of it was inherited from the past, an assumption

bolstered, for the

Works and

Days,

by the autobiographical presentation.

This is the origin of the gods we still revere today. This is how farmers

should plan their year now, be it the way they always have or not.

The structure of Greek societies around 700 B.C. was a simple one.

There was the

demos,

either the whole people or the people excluding

those who in Solon's later words 'had power'. At this time it was the

aristocrats who had power. There were also slaves and in a few cases,

but not in Boeotia, a class somewhere 'between free and slave'. Hesiod

was of the

demos

in its second sense, not perhaps so poor a member as

his surly grumblings might suggest, for he speaks of farm-labourers and

slaves, of mules and oxen, but what mattered in society was the line

between noble and commoner, not that between richer and poorer, and

Hesiod was of the commons.

2

A 71 Introduction; E 145.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

288 4

1

- CENTRAL GREECE AND THESSALY

His rulers

he

calls

basileis,

a

word which normally means ' kings'

but

here

as

elsewhere

can

hardly

be

pushed further

up the

social scale than

'lords'.

His

attitude towards them

is

somewhat equivocal.

In the

Theogony

(esp.

8off) they

are

eloquent and just, the fathers of their people,

in

the

Works

and

Days ruthless, corrupt, oppressive.

But

the

contradiction is easily resolved.

The

Theogony

may well have

been

the

poem which Hesiod sang

at the

games

in

honour

of the

nobleman Amphidamas

of

Chalcis;

for,

therefore,

an

audience

of

noblemen. Abuse would not have won

him the

tripod

of

which

he was

so proud {Works 654flF).

3

In

humbler circles

he

could tell

the

truth

as

he

saw it,

that some

basileis

were hungry

for

bribes, that some

basileis

behaved

as the

hawk

had

behaved

to the

nightingale

in the

fable:

Good bird,

why

all this twittering?

A stronger bird than you

Has

got

you, singer though

you be,

and what he will he'll

do.

{Works

207-9;

trs.

H.

T.

Wade-Gery)

But Hesiod

had one

friend

in

court,

the

highest court

of

all,

Olympian

Zeus himself who through his countless agents abroad on earth was kept

informed

of

crooked judgements

and of

straight ones

and

would deal

out prosperity

or

disaster as appropriate.

Here,

as in

other things, Hesiod stood

at a

moment

of

transition,

a

moment

of

questioning between blind acceptance

of

aristocratic rule

and revolt against it. Whether we

go

on to see him primarily as a private

grumbler with

a

private grudge against individual nobles

or as the

precursor of Solon, Aeschylus and Euripides for whom' the Nightingale

was

a

real power

in

Greek opinion

and

behaviour,

and the

Hawk

had

to listen

\

4

whether, that

is, he was

near

the

beginning

or the end of

question-time,

is of

little moment. What matters

is

that there

is an

element of generalization, the notion of

a

norm to which

a basileus

should

conform,

but at

the same time that there is no hint that he himself could

enforce conformity. There was only Zeus.

II.

BOEOTIA, 70O—5OO

B.C.

There

was

similar grumbling

in

other parts

of

Greece. Sooner

or

later

than that

of

Hesiod, more

or

less coherent,

we do not

know.

But it is

to these other parts that

we

must look

for its

translation into action.

In

our

area

the

spark remained unkindled.

The reason

is not far to

seek.

The

Boeotian plain

was

large enough

and fertile enough

to

keep Boeotians happy with

its

vegetables

and

3

Cf.

A

72 ad

loc.\

A

37,

79.

4

E

144,

12.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BOEOTIA

289

grain, the fowls of Tanagra and the eels of Lake Copais, and for the

rich, to support their horses (the team of one Pagondas carried off the

prize at Olympia in 680: Paus. v. 8.7). There was not much to tempt

a Boeotian to lift his eyes above the surrounding hills and mountains

to the sea, no great urge to colonize or to exploit the new economic

opportunities that came with or after colonization elsewhere. Access to

the sea was there, to the east or south-west to the Corinthian

Gulf;

the

possibility of maritime adventure could occur to Hesiod, as it did later

to Epaminondas, but one ferry-trip to Euboea was enough to satisfy

the one (while brother Perses was warned against anything more

daring), and the other's naval ambitions were short-lived. Boeotia, then,

was essentially an agricultural area, and a stale agrarian economy does

not breed social, political or even much cultural excitement.

As befits a country folk, the Boeotians were not unversed in music

and song. The tradition was that the legendary founder of Thebes,

Amphion, could charm stones to move with his lyre, the gift of the

Muses; more substantially, the noted reeds of Lake Copais furnished

Boeotians with the

aulos

(a clarinet- or oboe-type instrument) and a

famous school of innovators, performers and teachers

thereof,

famous

and fashionable

—

the great Pronomus of Thebes was tutor to Alcibiades

(Ath. 184D). At the same time, a country which can produce a Hesiod,

a Pindar or a Corinna is scarcely backward.

Similarly in peasant manner, religion flourished. The gods are

everywhere in Pindar and Hesiod as they were everywhere throughout

the countryside. There were oracular sites in plenty, of Trophonius at

Lebadia, of Ismenian Apollo in Thebes, Ptoian Apollo near Acraephia,

Amphiaraus at Thebes and Oropus; cults, some brought with the

migration from Thessaly, some local, of Athena Itonia at Coronea,

Artemis at Aulis, of Heracles and the Cabiri at Thebes, and hundreds

more.

5

Around these grew sanctuaries, some substantial, respectably

rich and not unattractive to foreign dedicators or competitors (Croesus

of Lydia made gifts to Amphiaraus; Athenians and others won prizes

at the games),

6

but nothing to raise the eyebrows, nothing to suggest

any startling Boeotian artistic inspiration.

There was some not utterly disreputable sculpture and bronzework

but pottery gives the fullest picture.

7

There, alongside much imported

Corinthian ware and some Attic, exists local work in quantity. But it

is

in the main derivative and dated

stuff,

no capturer of a foreign market.

From Geometric through orientalizing to black-figure the Boeotian

potter plodded along behind his Corinthian and Attic models and it is

hard to find studies which do not include judgements such as 'crudely

4

A. Schachter, The Cults

ofBoeotia

(1981-).

6

Hdt. 1. 52; A 36, 7j, 75, 91. '

H

29, 1005.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

s

m

Ml Parties i

GS

E

n

w

z

I-J

O

SB

W

w

n

w

>

z

a

w

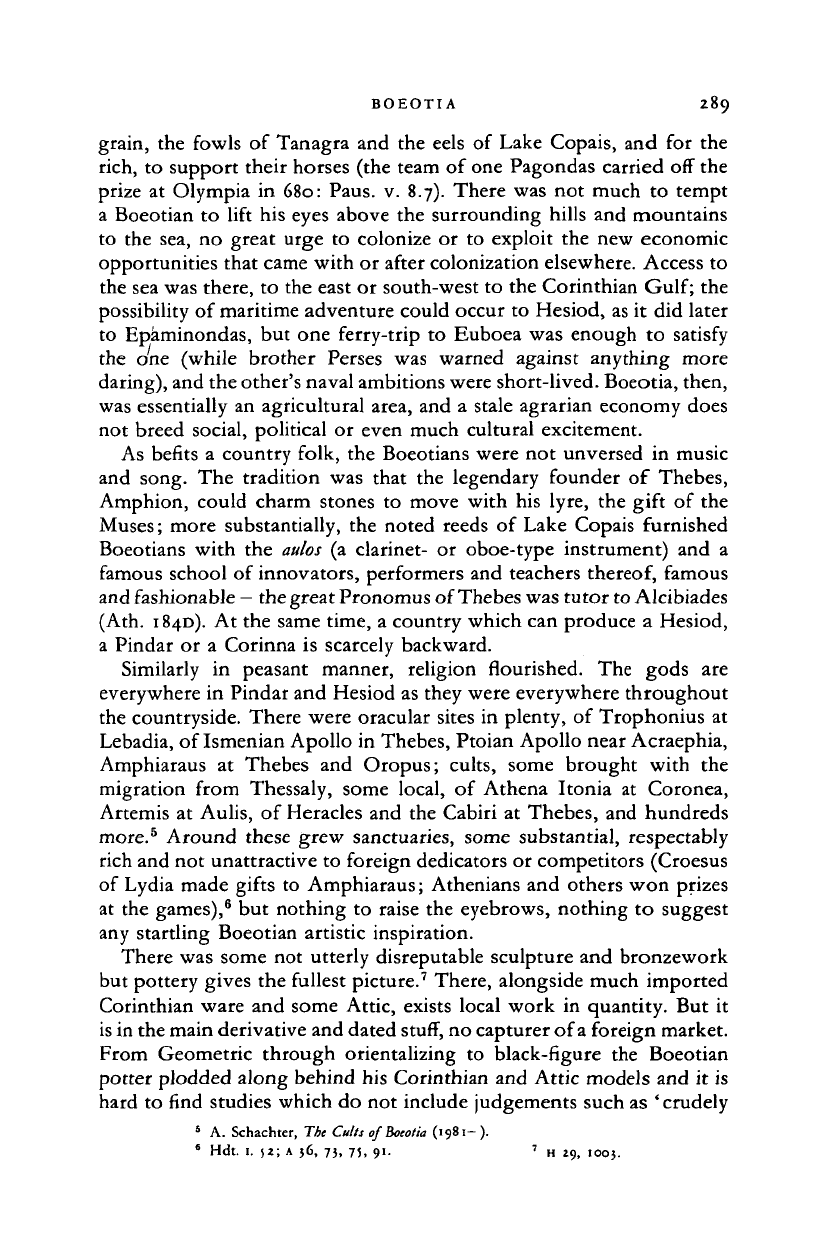

Map 16. Boetia.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BOEOTIA

2

9

I

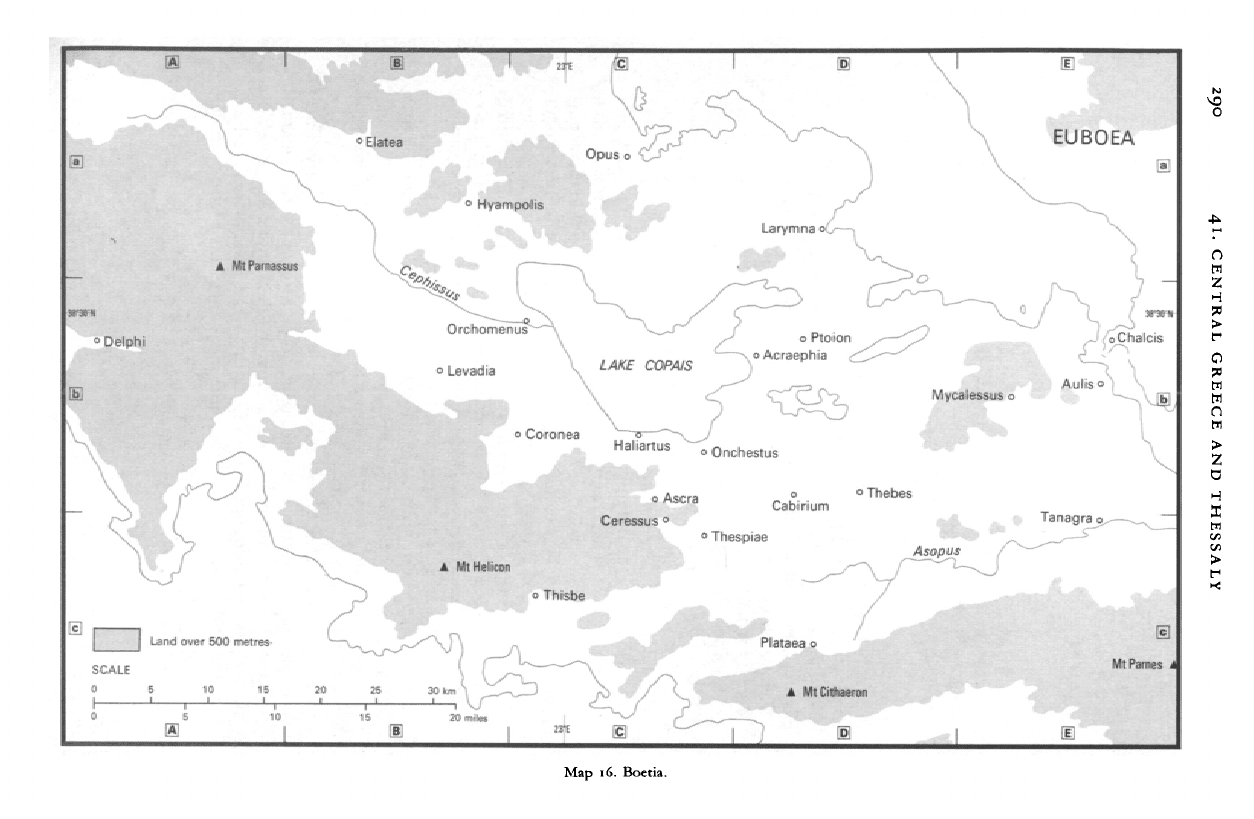

44.

A Boeotian 'bird-cup' from Thebes. Mid

sixth century B.C. Height 232 cm. (Paris, Louvre

Museum

A

;

72;

after

Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum

Louvre xvn, pi. 10.3.)

filled', 'primitive', 'humbly decorated'. There is only one original

group, the colourful and attractive 'bird-cups' (fig. 44) which roughly

span the sixth century - though even there the birds are often painted

upside-down (Boeotian taste, or painter's laziness?).

It is not that Boeotians were saving their talents for invention in other

directions. Of political development within the cities we hear very little

and that is almost certainly because there was little to record. Oligarchic

in 700 B.C., they were still oligarchic at the time of Xerxes' invasion.

One early 'law-giver' at Thebes is mentioned, Philolaus, a Bacchiad

nobleman from Corinth, whose activities, if tradition is correct, cannot

come much later than 700 (Arist.

Pol.

1274a). But given his background,

his measures are more likely to have been regulative than revolutionary.

Only one is recorded, a law of adoption designed to maintain the

number of property-owners. More interesting is the unanswerable

question

—

had an oligarchy of birth moved at all towards an oligarchy

of wealth? The likely descent of Pagondas, Boeotian general in 424,*

from the Olympic victor of 680 argues some survival of the former,

but there was once a law in Thebes, says Aristotle

{Pol.

1278325), which

permitted political office only to those who had abandoned commercial

pursuits for ten years. In the absence of date or context its import cannot

be judged (e.g. whether it was permissive or restrictive), but at least

it means that by the fifth century or before some Boeotians were selling

pigs as well as breeding them - and had political ambitions besides.

Indeed Herodotus at one moment mentions an ' assembly' in Thebes.

But how constituted he does not say and in practice a

'dynasteia

of a

few men' still ruled in 480

B.C.

(Hdt. v. 79; Thuc. in. 62).

' Thuc. iv. 91; cf. Paus. v. 8.7.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

41.

CENTRAL GREECE AND THESSALY

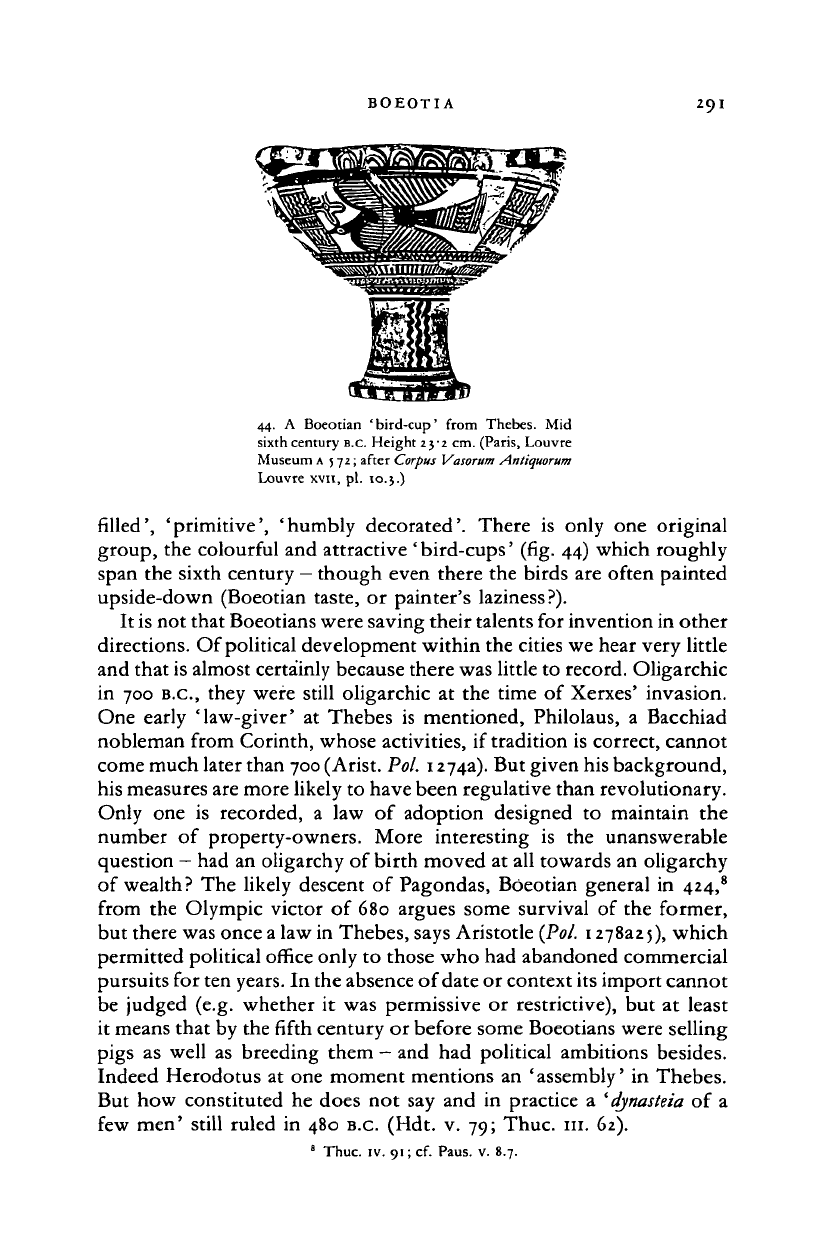

4;.

Reconstruction

of a

tripod dedication

at the

Ptoion

sanctuary. Late sixth century B.C. (After E 107, 1, pi. 15.1;

11,

49,

fig.

3; cf.

A

36, 93, pi. 8, no. 13.)

More significant, however, is the political structure

of

Boeotia as

a

whole. By the later fifth century

it

was

a

well-organized federal state,

dominated by Thebes, but unification had been slow and in our period

'Boeotia did this', 'Boeotia did not do that' are dangerous phrases

to

use without thought. Geography and racial identity imposed some sense

of unity celebrated by the festival

of

the Pamboeotia

at

the sanctuary

of Athena Itonia,

a

festival not attested before the third century

B.C.

though likely to be primitive.

9

But the unity it advertised will have been

more akin to that of the Panionia than the Panathenaea. There was no

political cohesion

to

back it,

at

least

at

the outset.

Homer lists no fewer than thirty-one contingents from Boeotia in the

Greek army before Troy, and though the number had been reduced by

destruction, abandonment or absorption, there were still a dozen or so

independent cities

in

existence around 700, among them Orchomenus

and Coronea to the west of Lake Copais, Thespiae, Haliartus, Thebes,

Acraephia to the south and east and further south again, on or near the

border with Attica, Plataea, Tanagra and Oropus. Factors encouraging

separatism were many, pride in past glory (Orchomenus had once been

• See n.

5.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BOEOTIA 293

46.

Silvercoin of Haliartus. Late sixth century

B.C. (London, British Museum; after BMC

Central Greece pi. 7.14.)

mighty and was still a serious rival to Thebes), the hostility of close

neighbours (Thespiae was only about 24 km from Thebes), religious

rivalry (Thebes coveted Acraephia's Ptoion), proximity to other states

(Larymna wavered between Boeotia and Locris, Oropus between

Eretria or Athens and Thebes, Plataea was drawn towards Athens).

There are too many variables and a sad lack of evidence.

Excavations at the Ptoion are invoked to place Theban encroachment

there early in the first half of the sixth century.

10

Two sanctuaries are

involved, one at Perdikovrysi (Apolline), one at Kastraki nearby

(belonging to the hero Ptoios), and, the argument runs, it was when

Apollo, under Theban pressure and bringing with him Theban rites,

moved in to Perdikovrysi in the late seventh century, that the locals of

Acraephia transferred the hero to Kastraki and with him the custom

of dedicating tripods in his sanctuary (fig. 45). But the chronological

and dedicatory patterns are not clear enough to impose such a simple

story. That the establishment at Kastraki was later, that there was some

shift in tripod concentration, that there was a close resemblance of the

Apollo cult with that of Ismenian Apollo at Thebes, and that Thebes

expanded northwards at some point, these are all facts, and perhaps are

best explained by some rather more haphazard version of the same

account, but a further suggestion that the fight in southern Thessaly

between (Theban) Heracles and Cycnus, retailed in the Hesiodic

Shield

of

Heracles,

reflects Theban ambitions still further north at the same

period rests more on hope than evidence.

11

Later in the century, certainly not before 550, appears the first

Boeotian coinage (fig. 46),

12

a common 'federal' type marked by a

Boeotian shield on the obverse, from Tanagra and Haliartus (identified

by their initials) and from Thebes, significantly without an initial. To

these a second issue, from about the end of the century, adds mints

at Acraephia, Coronea, Mycalessus and Pharae (near Tanagra). Mean-

while, however, Orchomenus had begun to advertise its continued

10

E 107, 116-34 and review;

E

96;

E

97, 437-50; cf. in general E 120, 11, in.

11

E 109, 79-84.

12

H 48, 108-10.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

294 4

1

- CENTRAL GREECE AND THESSALY

independence, real or imagined, with an issue of its own, an ear of corn

in place of the shield and on the reverse an incuse following Aeginetan

types

(a

recollection

of

past association?)

13

while

a

dedication

at

Olympia of the third quarter of the century celebrates an Orchomenian

victory over (already federated?) Coronea.

14

Thus

it

would seem that by about 500 Thebes controlled the whole

of Boeotia south

of

Copais. Or almost.

In

506 the Thebans recite the

names

of

some loyal, local allies, the men

of

Thespiae,

of

Coronea, of

Tanagra (Hdt.

v.

79.2). One name is missing, that

of

the little city of

Plataea, south-west across the Asopus river, which, possibly

in

519,

15

had appealed

to

Athens against Theban pressure, and with Athenian

(and some Corinthian) help had saved her autonomy, help which she

more than repaid

at

Marathon and then on her own doorstep in 479.

One thorn

in

the flank of the Boeotian pig.

III.

THESSALY,

7OO—

JOO

B.C.

Thessaly is little other than a bigger and better Boeotia.

A

still larger,

even flatter plain, surrounded

by yet

more formidable hills

and

mountains which gave only one opening

to

the sea

at

the south-east

corner. True, this was

to the

superb natural shelter

of

the Gulf

of

Pagasae through which foreign influence had spread well into the heart

of the country in early centuries. But, by and large, we are dealing with

another self-sufficient, stable agricultural society.

In earlier days young Jason had been able

to

acquire

a

gentleman's

education at the feet of the centaur Chiron before becoming Thessaly's

only great merchant-explorer, and Achilles learnt enough

of

the lyre

to accompany

his

barrack-room ballads before Troy; later

a

much-

embroidered tale may conceal

a

real colonial venture

via

Crete

to

Magnesia on the Maeander;

16

throughout the Dark Ages a combination

of imported and local inspiration produced unpretentious but present-

able Protogeometric and (less confident) Geometric pottery.

17

But,

after about 700, there

is

little

of

native culture

or art

(beyond

a

line

in miniature bronzes), no interest

in

the world abroad. Alcman sums

U

P'

He was no rustic boor, nor a lubber.. .nor a

Thessalian by race...(fr. 16 Page: trs. Bowra)

The

basileis

who exploited the riches

of

the plain and controlled its

cities,

Larissa and Crannon to the north-east, Pharsalus and Pherae in

the south, are a little more real than those of Boeotia

—

at least we have

13

See

n.

12; P-Wn 'Kalaureia'.

I4

A 36, 93, no. 11.

15

Hdt. vi. 108; Thuc. in. 68 (for the date, Gomme, ad loc).

16

E 130, nos. 378-82.

"

H 25, 158-63.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008