Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4 INTRODUCTION

achieving a tentative, fragile stability under the Carolingian rulers of the eighth

and ninth centuries. After the Carolingians, a second period of disarray descended,

until at some point in the eleventh century Europe quite literally rebuilt itself—

physically, politically, spiritually, economically, and socially—and entered a period

of impressive expansion, wealth, stability, and intellectual and artistic revival.

Many of those gains were lost, as we shall see, in the calamities of the fourteenth

century; but by that point the foundations were securely laid for Europe to move

into the Renaissance with both the technological and economic means, and the

ideological convictions, that would prepare Europe to dominate the globe. The

long centuries of the Middle Ages saw western Europe transform itself from a

sparsely populated, impoverished, technologically primitive, socially chaotic, and

often barbaric place to the world’s wealthiest, best educated, most technologically

developed, and most powerful civilization to date. As we shall see, much of that

transformation depended precisely on the ways in which the many worlds of the

Middle Ages tried to fashion the connections and conflicts of everyday life into a

unified vision of human existence.

Part One

PART ONE

8 8

T

H

E

E

A

R

L

Y

M

I

D

D

L

E

A

G

E

S

T

h

e

T

h

i

r

d

t

h

r

o

u

g

h

N

i

n

t

h

C

e

n

t

u

r

i

e

s

T

h

e

T

h

i

r

d

t

h

r

o

u

g

h

N

i

n

t

h

C

e

n

t

u

r

i

e

s

This page intentionally left blank

7

CHAPTER 1

8

T

HE

R

OMAN

W

ORLD AT

I

TS

H

EIGHT

T

he Roman Empire of the first and second centuries a.d. comprised the larg-

est, wealthiest, most diverse, and most stable society of the ancient world.

No other ancient empire—not the Assyrian, not the Persian, not the Athenian—

had succeeded on such a scale at holding together in harmony so many peoples,

faiths, and traditions. Historians commonly describe these two centuries as the

period of the Pax Romana (“the Roman Peace”), an age when a strong central

government engineered and maintained the social stability that allowed people to

prosper. The sheer vastness of the empire was astonishing: It stretched over three

thousand miles from west to east, from the Strait of Gibraltar to the sources of the

Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and reached northward to Hadrian’s Wall, a fortifi-

cation built in a.d. 122 to protect Roman Britain from the Picts of Scotland, and

southward to the upper edge of the Sahara. Within this vast territory lived as

many as fifty to sixty million people.

The prosperity of those centuries came at a high cost. Rome’s rise to power

was the result of military might, after all, and long centuries of warfare had pre-

ceded “the Roman peace.” In the bloody Punic Wars of the third century b.c. Rome

defeated Carthage, its main rival for control of the western and central Mediter-

ranean, before turning its eyes aggressively eastward and subduing the weakened

Greek states left over from the collapse of Alexander the Great’s empire. But soon

after it had conquered the known world, the Roman state went to war against

itself: Civil wars raged for well over a century as various factions struggled not

only to control the new superstate but to reshape it according to opposing prin-

ciples. Some factions favored preserving the decentralized administrative practices

of the early Republic, while others, such as the faction led by Julius Caesar, cham-

pioned a strong centralized authority; some favored a rigid aristocratic authori-

tarianism, while others promoted a more radically democratic society. These long

wars ended in a bizarre compromise. The empire of the Pax Romana period was

a thoroughly centralized state that delegated most of its day-to-day authority to

local officials; and it was a decidedly hierarchical society, almost obsessive in its

concern to define every individual’s social and legal classification; and yet it re-

mained a remarkably fluid world in which a family could rise from slavery to

aristocratic status in as few as three generations.

Two factors did the most to shape the Roman world and foster its remarkable

vitality and stability: the Mediterranean Sea and the Roman army.

T

HE

G

EOGRAPHY OF

E

MPIRE

The Roman world, like the medieval world that succeeded it, was centered on the

Mediterranean. The sea provided food, of course, but more importantly it

8 THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

provided an efficient and ready means of transport and communication. When the

Romans referred to the Mediterranean as mare nostrum (“our sea”) they were not

being merely possessive but were in fact recognizing that the sea was the essential

physical infrastructure that held together the entire Roman world. As a general

rule in human history, seas do not divide people; they unite them. This is espe-

cially true of the Mediterranean. Since the Strait of Gibraltar—its opening to the

Atlantic Ocean—measures only eight miles across, the Mediterranean has very

little tide-variation and is naturally protected from all but the worst of Atlantic

storms. With the sea’s smooth waters and temperate climate, sailors from the ear-

liest centuries found it easy to traverse the Mediterranean even in primitive ves-

sels. Moreover, since early navigation relied more on using coastal landmarks than

on steering by the stars, the sea’s natural division into two basins and its abun-

dance of islands and peninsulas enabled traders to reach faraway ports without

ever losing sight of land. These geographical features meant that in Roman times,

and even many centuries before Rome, peoples from regions as far apart as south-

ern Spain and northern Egypt could be, and were, in regular if not continuous

contact with one another.

In fact, they had to be. The Mediterranean basin is surrounded by mountains

along its northern and eastern shores and by deserts along its southern expanse.

This relative shortage of hinterland, coupled with the basin’s characteristic long

summer droughts, meant that most Mediterranean coastal societies had difficulty

producing locally all of the foodstuffs and material goods necessary to life, and

hence they had to trade with one another in order to survive. The physical char-

acteristics of the sea made such contact possible. One should therefore think of

the various cultures of the Mediterranean world as component parts of a single,

large sea-based civilization linked by similar agricultural techniques (the need for

terracing the arid hinterlands and the use of sophisticated irrigation networks, for

example), similar diet (with olive oil, wine, hard grains, and fish predominating),

and similar social organization (the norm was independent coastal cities domi-

nated by trade, and therefore by traders and tradesmen, rather than by large-scale

landowners). Thus when the Romans referred to “our sea” they meant not just

the body of water controlled by the Roman administration, but the body of water

that itself controlled the lives of the empire’s inhabitants.

Roman adminstration of its vast empire would in fact have been impossible

without the sea. No matter what an emperor may have thought of himself and

his authority, his real power extended no further than his ability to enforce his

will, and the qualities of the Mediterranean were such that the emperor’s power

stretched very far indeed. Well-equipped ships fanning out from Rome could scat-

ter throughout the entire sea in two weeks. In ideal sailing weather, for example,

a ship could reach Barcelona in only four days; a fleet setting out for Alexandria

could drop anchor there in little more than a week. This fact allowed Roman law,

and the military muscle needed to enforce it, to be put into direct and effective

practice. The news of local rebellions reached Rome quickly, and Roman forces

were just as quickly dispatched to the trouble spots before the rebellions had a

chance to grow. No land-based empire could hope to possess the political, com-

mercial, and cultural cohesiveness offered by the Mediterranean.

And in fact, it was when Rome began to extend its dominion away from

the sea basin that its first difficulties arose. Rome’s eastward expansion into the

Tigris-Euphrates river valley brought the empire into contact, and instantly

into conflict, with the Parthian Empire, but it was the northern reach of the empire

into western and central Europe that proved the greatest risk to Roman order. A

9

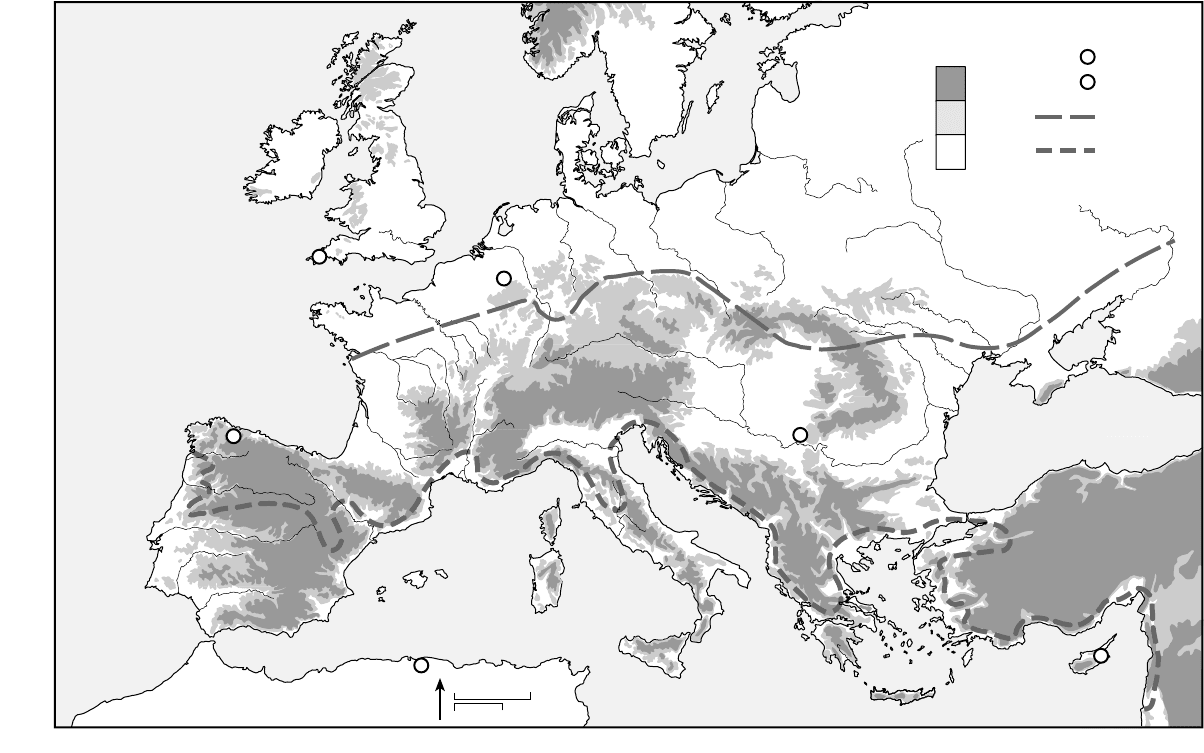

PYRENEES

ALPS

BALKAN MTS

CARPATHIANS

C

C

C

T

T

C

H

A

R

D

W

O

O

D

F

O

R

E

S

T

H

A

R

D

W

O

O

D

F

O

R

E

S

T

Tagus

Ebro

Rhône

Garonne

Saône

Seine

Loire

Rhine

Elbe

Weser

Vistula

Oder

Po

Danube

Drava

Danube

Danube

Rhine

Dnieper

Pripyat

Dnieper

Dniester

Prut

Bug

Don

0

200 Miles

0

200 Kms.

N

E. McC. 2002

ATLANTIC OCEAN

North Sea

Baltic Sea

Adriatic Sea

Black Sea

MEDITERRANEAN SEA

MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Tyrrhenian

Sea

Ae gean

Sea

C

Generalized

Topography

(feet above

sea level)

2000

1000

0

Natural

Resources

Copper

Tin

T

Northern

Limit

of Grapes

Northern

Limit

of Olives

The topography of Europe

10 THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

series of mountain ranges had always protected the Mediterranean world from

the less advanced nations of the European continent. The Pyrenees mountains

offered a strong border protecting Roman Spain from the Celts of Gaul (modern-

day France), while the Alps and Balkan mountains had always shielded the Med-

iterranean from the numerous Germanic and Slavic peoples. But in the first cen-

tury b.c. a Celtic group known as the Helvetii were driven from their homelands

beyond the Rhine and Danube, and settled first in the area that today makes up

Switzerland before migrating further westward across the territory of central

France. This mass movement threatened the Roman province of southern Gaul,

and in order to defend it Julius Caesar began his long campaigns to push the

Roman frontier northward. These campaigns began Rome’s larger involvement in

continental Europe, and the subsequent need to find a strategically defensible fron-

tier ultimately pushed her borders all the way to the Danube and Rhine rivers

and to northern England.

Continental Europe was a decidedly different place from the world of the

Mediterranean. Comprised chiefly of a vast wooded plain, beginning in southern

France and reaching northward to England and Scandinavia and eastward through

Germany, Poland, and Russia, it was a world of immense, if still largely untapped,

natural resources. Dense hardwood forest covered most of the land, offering abun-

dant material for building. The land itself, once cleared, was heavy and wet. This

made it more difficult to work than Mediterranean soil—heavier plows and

stronger draught animals were needed, for example, and more collective labor—

but it could produce two crops a year. Cereal production dominated here, unlike

the viticulture (grape and olive vineyards) of the south. Given the density of the

forest, the numerous rivers of the north served as the main conduits of commerce

and contact. Continental Europe therefore could support a large population, but

the conditions of the land meant that settlements were widely scattered and iso-

lated from each other. In Roman times, less than ten percent of this land was

inhabited. People tended to cluster around clearings they had carved out of the

forest and to carry out the whole of their lives there, working the soil. Goods

could be traded up and down the river valleys but not over the land itself.

Northern groups thus had considerably less contact with one another than Med-

iterranean peoples did, and they developed clannish and conservative cultures

that were resistant to change and suspicious of outsiders. That is why the immi-

gration of a large number of newcomers, such as the Helvetii, could set off such

widespread unrest. Continental life in the ancient world therefore remained more

disparate and static, and also more fragile, than Mediterranean life, and these

features made it more difficult to administer. Unlike the urban scene that charac-

terized the south and supported Roman administration, the rural and sedentary

north was brought into the Roman world, and was maintained in it only by mil-

itary occupation.

T

HE

R

OLE OF THE

M

ILITARY

The army was the second chief structure on which the Roman Empire was built

and it differed significantly from the other military forces of the ancient world.

Semiprivatized in the period of the Republic, it came to possess an extraordinary

degree of organization and professionalization under the emperors. Soldiers

fought for the glory of the Roman state, but also for regular wages and a portion

of whatever booty they could haul away from whomever they conquered. After

THE ROMAN WORLD AT ITS HEIGHT 11

subduing a region, the army confiscated whatever money was at hand, carried

away whatever portable property they desired, divided up the choicest bits of real

estate they fancied, and sold into slavery the prisoners of war they had captured.

War was a highly profitable business. Because of the natural wealth inherent in

continental Europe, inland Egypt, and the Near East (the three main sites of Roman

aggression—the first taken largely by Caesar and Claudius, the second by Au-

gustus, and the third by Hadrian) the army’s success in pushing the Roman fron-

tier forward brought in enormous amounts of money that, until the later decades

of the second century, more than compensated for the cost of the warfare itself.

The army as a rule did not permanently occupy the lands it had conquered.

To do so might have prolonged local resentments; but permanent occupation was

also unnecessary, given the ease of transporting soldiers across the sea. A more

commonsense approach called for conquering a region, redrawing the local ad-

ministrative practices along Roman lines (although usually keeping the local elites

in power), then withdrawing the troops at the first available moment. They could

always return quickly enough, if events warranted it. For this reason, a permanent

military presence is a remarkably reliable indicator of where the trouble spots

were. Continental Europe, as it happened, had the longest, largest, and most per-

manent network of garrisons. Resistance to Roman power had been strong, but

the main threat to stability came from the difficulty of administering so vast an

expanse of land. The sedentary rural populace did not experience the daily inter-

action with other cultures that the south did, and this meant that they were more

resistant to “Romanization.” And since troops could not deploy with the same

ease that they could in the south, the only alternative was permanent settlement.

The greatest concentration of troops existed along the furthest borders of the em-

pire; but a careful network of smaller military camps stood behind them, stretching

from the Atlantic opening of the Loire to the mouth of the Danube at the Black

Sea.

The army’s significance rested upon more than its record of battlefield victo-

ries, for the army was the single most important instrument for “Romanizing” the

conquered peoples and turning them into peaceful elements of a stable society.

The army accomplished this transformation by charting a new direction in social

engineering. Earlier empires, such as the Athenians of the fifth century b.c., had

steadfastly maintained a separation of the conquerors and the conquered, and

ruled over their realms with very little interaction with their subjects. Roman prac-

tice was different. They enlisted soldiers from all ethnic groups throughout their

empire—Italians, Egyptians, Celts, Dacians, Hibernians, Libyans, and more—and

used them to help bring Roman culture to the provinces. Soldiers learned to speak

Latin, to know and obey Roman law, to practice Roman religion. Soldiers served

for twenty years, during which time they were stationed in province after province

(but almost never in their native territory), were encouraged to intermarry with

local women, and at the end of their service received a handsome severance pay-

ment of cash and/or land. This practice produced two important results. First, the

empire had a steady stream of volunteer recruits attracted by the opportunity to

make money, see the world, receive an education, earn an honored place in society,

and retire at an early age with land to farm and money to fund the operation.

(The empire at its height boasted of a military force, including auxiliaries, of three

hundred thousand men.) Second, army service had the intended effect of eroding

an individual soldier’s sense of identification with his native ethnic group and of

inculcating his self-definition as a “Roman”—that is, as a member of a society and

civilization that was larger than mere ethnicity. To be a citizen of the empire

12 THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

implied something more than a mere legal classification; it meant that one be-

longed to and represented an ideal of social organization, a vision of human unity

and cohesion. Roman civilization, in other words, resulted from the intentional

blending of cultures and races, and whereas Roman religion, administration, ar-

chitecture and urban design, literature, and art all contributed to “Romanization,”

the army played the first and most important role in that process.

R

OMAN

S

OCIETY

But while Roman society in the first and second centuries a.d. was stable, it was

hardly static. Sharp distinctions of social and legal class existed, but since one’s

class was determined more by one’s wealth than one’s ancestry, individuals could

frequently pass from one stratum to another in the hectic and prosperous days of

the Pax Romana. A sense of public spirit was required as well, since Roman tra-

dition expected the rich to put their personal wealth to public use—either to build

or maintain roads, repair aqueducts, feed and house troops, or aid the poor. The

essential social distinction lay between the honestiores (“the better people”) and the

humiliores (“the lesser people”), yet important gradations existed within each

group. The honestiores enjoyed significant legal protections, such as the right to

lighter penalties, if they were convicted of a crime, and immunity from torture.

The humiliores, by contrast, fared far worse, even if they held Roman citizenship.

A “lesser person” convicted of a capital crime such as murder or treason had to

face a brutal death by being torn apart by wild beasts or by crucifixion, which

killed by slowly constricting the circulatory system.

Four main groups made up the honestiores: senators, equestrians, the curiales,

and all army veterans. Out of a total population of fifty to sixty million at the

empire’s zenith, roughly one thousand men, and their immediate families, quali-

fied for the senatorial order; this class derived its name from the fact that they

alone had the right to serve in the Roman Senate. Considerably larger was the

class of the equestrians, which numbered perhaps fifty thousand. In earlier times

the equestrian order had comprised those who had served in the Roman cavalry,

although by the first two centuries a.d. merchants, financiers, and large property-

holders predominated. Custom demanded that an individual had to come from a

family that had been free-born for at least two generations before being admitted

to this order—an indication of the flexibility of Roman class consciousness. Just

below the equestrians stood the rank of curiales. This was the largest of the priv-

ileged classes, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, and by the third century

they were the most significant. Curiales served as unsalaried magistrates who

conducted the day-to-day administration of the cities and towns. A unique char-

acteristic of the class of curiales is that in this order alone a woman who held the

social rank could also hold the political authority that might accompany it. Army

veterans were also numerous, but since they tended to retire after their service to

rural estates, they generally played larger roles in local political and social affairs

while exercising little collective influence over high imperial matters.

The humiliores consisted of everyone else in the empire (except for slaves,

whom the law regarded as property). The overwhelming majority of these “lesser

people” worked on the land either as free farmers, tenants, or hired hands on a

great estate. Skilled and unskilled laborers, craftspeople, merchants, and clerks

made up the free commoners in the cities. As for the slaves, the females were

usually reserved for domestic service—in part to keep them available for sexual

THE ROMAN WORLD AT ITS HEIGHT 13

exploitation by their masters—but the males were especially vital throughout the

urban and rural economies, working in homes, shops, fields, quarries, and mines.

Slaves of Greek origin frequently worked as tutors to children.

The economy grew as the empire grew. Naturally, the sheer internal peace

and order of the empire encouraged economic growth, but we can identify a few

specific causes of the general prosperity of these years. One obvious influence was

the army. Unlike today’s military forces, ancient armies had few stockpiles of

weaponry, equipment, transport vehicles, blankets, or food. These supplies had to

be procured, and therefore produced, wherever the soldiers traveled. The twenty-

five legions of the Roman army needed vast stores of food, clothing, and ironwork

every day and thus represented itinerant mass markets that constantly spurred

local production. It took the hides of fifty thousand cattle, for example, to make

the tents for a single legion. Moreover, legions on the march often built new for-

tified camps as they progressed—complete with central command buildings,

guard posts, and wooden walled perimeters—that formed the nuclei of permanent

settlements once the army moved on. These settlements frequently became centers

of exchange for local farmers and manufacturers, and occasionally grew into full-

fledged cities.

1

As these local economies became more sophisticated, regional trade

increased. The agricultural abundance of northern Europe was carted south and

soon rivaled the traditional grain-producing centers of Sicily and Egypt. Tech-

niques of Mediterranean olive- and grape-viticulture traveled northward. Spices

and silks came from the eastern provinces, and animal products dominated the

exports of inland Spain.

The family formed the basic unit of society and economic production. In Ro-

man times the word familia meant “household” rather than “family” in the modern

sense, and it included wives, sons, daughters, concubines, attendants, servants,

and slaves. The Roman family thus was a larger, more inclusive institution than

we are accustomed to, but hardly more benevolent for it. Characteristically for the

ancient world, society was rigidly patriarchal. Fathers possessed a legal authority

known as patria potestas (“paternal power”) that gave them, quite literally, control

of the very lives and deaths of all the members of their families. If circumstances

warranted it, a Roman father had the right to put to death any member of his

family at any time. Acts this grave were usually limited to exposing unwanted

babies soon after birth—whether to avoid having an extra mouth to feed during

economic hard times, for example, or to get rid of a physically defective child—

but in theory a father could legitimately kill anyone under his authority, free or

unfree, male or female, young or old. The law also recognized the father as the

sole possessor of a family’s property. Anything acquired by anyone in the family

belonged, in theory, to the father alone. But it remains unclear how often these

theoretical powers were actually put to use.

Wives represented a partial exception to paternal power. Older Roman tra-

dition held that a daughter remained under her father’s authority until her mar-

riage, after which she fell under the power of her husband (unless in their mar-

riage contract the husband specifically relinquished this right). However, by the

Pax Romana period most Roman marriages were “free”—meaning that the hus-

band never succeeded entirely to the father’s power. Thus a grown woman,

whether married or not, could live a relatively independent life after the death of

her father. She could own property, run a business, save her own money. Women

1. Laon, in northern France, is an example.