Anderson J.M. Daily Life during the French Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

180 Daily Life during the French Revolution

in fact, relieve the large family of the extra mouth to feed, and the girl also

might be able to send a little money home once in a while. Paris was gener-

ally the preferred destination for such young people.

6

The working life of

a single girl in the city was not an easy one. Girls who became apprentices

worked hard for meager pay, slept in dormitories, and had little to eat. On

Sundays, about half a dozen pounds of meat were stewed in a large pot; this

had to feed everybody in the workshop for a week. The woman in charge

sent the girls out on occasion to the local markets to purchase bread at a

price much cheaper than in the bakeries, and it, too, had to last the week.

Walking through the streets of Paris during the time of the Terror could

be a traumatic experience, especially for young girls or boys straight from

the country. Cattle carts passing by on their way to the river were some-

times piled high with the bodies of men and women recently butchered.

As the wagons bounced over the cobblestones, arms and legs dangled

from the sides like puppets on a string, trickles of fresh blood falling on the

roadway. At the river, the bodies and their separated heads were thrown

into the water to drift downstream toward the ocean. Only a short time

before, the victims had made the journey in the same tumbrels down the

rue St. Honoré to the guillotine. Working in their shops as the carts passed,

Parisians often didn’t even look up, according to eyewitness reports, or

turned their backs on the gruesome spectacle.

When people went into the streets of Paris, they made sure they were

wearing the tricolor cockade on their hats, which identifi ed them as patri-

ots, whether they were or not. It was not wise to reveal any subversive

characteristics or thoughts to anyone at anytime. To be denounced as a

traitor could mean a place in the tumbrels.

THE PARIS QUARTERS

Not unlike many other large European cities, Paris was composed of

many districts or quarters, each with its distinct people and atmosphere.

The wealthy middle class and the nobility occupied the faubourg St. Germain,

as well as the Marais, the Temple, and the Arsenal districts.

7

The working-class areas had their special occupations: the masons lived

in St. Paul; the furniture and construction industries were situated in

Croix-Rouge; and milliners, haberdashers, and producers of other fash-

ionable goods inhabited the rue St. Denis and the rue St. Martin.

To the north of the city, the residents of the suburbs of Montmartre,

St. Lazare, and St. Laurent were engaged mainly in the sale of cloth. In

Chaillot, to the west, were ironworks and cotton mills, while the suburb

of Roule, known as Pologne (Poland, as it was the home of many Polish

immigrants) was one of the poorest neighborhoods in Paris. East of the city

on both banks of the Seine lay the suburbs of St. Antoine and St. Marcel,

where furniture workshops were situated, along with the Gobelins tapes-

try works, dye works, and Réveillon’s wallpaper factory.

Urban Life 181

Doing the same jobs, frequenting the same taverns, and marrying local

girls, the workers seldom ventured beyond their districts. Events happen-

ing in one section of the city were not even known about in others, as peo-

ple were generally indifferent to what was going on elsewhere. Diffi culties

of transportation and traffi c compartmentalized the city, and reactions to

political events were different in the various sections.

Housewives shopping at the local market might be totally unaware that

people were being massacred nearby. News, spread by word of mouth,

could take several days to reach all parts of the city, and everything was

extremely susceptible to exaggeration and rumor.

For those curious people willing to travel further afi eld to hear the most

recent news, there were meeting places where discussions took place.

The Jardin des Tuileries, earlier a fashionable parade ground, became the

open-air anteroom of the Assembly, and the Place de la Grève was used

for executions, mass gatherings, and parades of the National Guard. The

most popular meeting place was the gardens of the Palais Royal. Here was

the center of cafe life, restaurants, entertainment, and the favorite haunt

of agitators, soapbox orators, rabble-rousers, scandalmongers, prostitutes,

and demagogues. The galleries along the arcaded sidewalks had been

rented out to tradesmen by the duke of Orléans some years before and

had become the noisiest and, for the future of the royal crown, the most

dangerous place in the city.

The marquis de Ferrières, a provincial nobleman, having visited the

Pa lais Royal, stated:

You simply cannot imagine all the different kinds of people who gather there. It

is a truly astonishing spectacle. I saw the circus; I visited fi ve or six cafés, and no

Molière comedy could have done justice to the variety of scenes I witnessed. Here a

man is drafting a reform of the Constitution; another is reading his pamphlet aloud;

at another table, someone is taking the ministers to task; everybody is talking; each

person has his own little audience that listens very attentively to him. I spent almost

ten hours there. The paths are swarming with girls and young men. The book shops

are packed with people browsing through books and pamphlets and not buying

anything. In the cafés, one is half-suffocated by the press of people.

8

Most visitors never ventured into the old quarters but stayed in the

hotels in the more affl uent areas. However, that the capital was lively,

noisy, and vivacious is evident from reports of foreigners who visited the

city. A German bookseller and writer named Campe, who visited Paris in

1789, noted that not only were the people polite and animated in conver-

sation but also that everybody was

talking, singing, shouting or whistling, instead of proceeding in silence, as is the

custom in our parts. And the multitude of street vendors and small merchants try-

ing to make their voices heard above the tumult of the streets only serves to make

the general uproar all the greater and more deafening.

9

182 Daily Life during the French Revolution

Campe, a refi ned gentleman from a sedate and somewhat dull country

compared to France, went one evening to watch the sunset from the Place

Louis XV and suddenly found himself assailed by three old harpies who

tried to kiss him and at the same time snatch his purse. Fortunately, he

got away unscathed. Some witnesses found life in Paris harrowing, with

the crowds, noise, smells, dirt, and abundance of people from the prov-

inces looking for work, some of whom were desperate for a handout of

a few sous. A lot of these wound up working in the quarries of the Butte

Montmartre.

Some 4,000 of the nobility lived in Paris. The revolution brought about

the fi rst exodus of aristocrats from the city on July 15, 1789; the second and

larger one took place after October. Those who remained found life rather

boring, since there were no more grand balls and even concerts had been

eliminated. Night patrols kept the streets peaceful and aristocrats indoors.

As people left the richer districts for exile, trade slowed down and money

became scarcer.

A NOBLEMAN IN THE ESTATES-GENERAL

The marquis de Ferrières, a public fi gure in Poitou, divided his time

between his chateau in Marsay and his grand house in Poitiers.

10

A stu-

dent of the philosophers of the Enlightenment, he published three essays

on the subject. His satire on monastic vows earned him a reputation as

an intellectual and led the nobility of Poitiers to elect him as their repre-

sentative to the Estates-General. He kept up regular correspondence with

his wife after his arrival at Versailles. Like the majority of deputies, he

deplored the move to Paris and complained that the streets of the city

were rivers of mud in the constant rain and that he did not go out at night

for fear of being run over by carriages. Instead, he spent the time alone and

sad, seated by the fi re. He invited his wife to join him in Paris, but they

needed servants, so he asked if the cook at Poitiers would be able to dress

her mistress? Would she sweep the fl oors and make the beds? If she was

not agreeable, he would rather have the little chambermaid, who could

help with the washing and manage some cooking. Madame de Ferrières

arrived in Paris and passed two winters there, but in the summers of 1790

and 1791 she returned home and her husband continued to write to her

about domestic affairs. In August 1790, the marquis stated that he was

highly satisfi ed with Toinon, his servant, who gave him every attention,

and wrote about his diet, which consisted of beans, haricots, cucumbers,

and very little meat. He dined with another noble deputy from Béziers,

who shared expenses with him helping to keep costs down. He declared

that in the preceding month, the cost of provisions (butter, coal, vegeta-

bles, fi sh, and desserts) had amounted to 118 livres, and bread had cost

another 30 livres. This sum did not include meat and wood, or lodging

at three livres a day. Toinon was later replaced by a girl, Marguérite, who

Urban Life 183

was excellent at making vegetable soup. The staff also included a man-

servant called Baptiste, a short, jolly man who liked coffee and sneaked a

cup whenever he could, ate too much meat, and spent his free time enter-

tained by the marionettes in the Place Louis XV. The marquis said he had

only one serious shortcoming: when he went down to the wine cellar, he

always came back reeking.

CAFE SOCIETY

In the summer of 1789, cafe society was in full swing, and there was more

to discuss and argue about than ever before. The tables on the sidewalks

were packed with people sipping everything from English and German

beer to liqueurs from the French West Indies, fruit drinks, wine, Seidlitz

water, and a host of other cathartic and herbal tonics, as well as coffee

and chocolate-fl avored drinks. Signboards advertising the cafes were on

every corner, gallery, and arcade. In front of the famous cafe Caveau, great

throngs gathered until two in the morning. Each establishment was well

known for some specialty: the Grottes Flamande for its excellent beer, the

Italien for its beautiful porcelain round stove, and the Café Mécanique for

the mocha pumped up into patrons’ cups through a hollow leg in each

table. Of the many and varied places, the Café de Foy was the most popu-

lar of all, with its gilded salons and a pavilion in the garden. A fi ne brandy

from the provinces was its trademark.

In the rue des Bons-Enfants stood the Café de Valois, frequented by

many of the Feuillants reading the Journal de Pari s, while the Jacobins were

regular patrons of the Café Corazza, where François Chabot and Collot

d’Herbois often held the fl oor. In the rue de Tournon was the Café des Arts,

the focal point of the extremists from the Odéon district, while more mod-

erate types congregated at the Cafe de la Victoire, in the rue de Sèvres. The

differences in clientele could be striking. At the Régence, on the right bank

of the Seine, Lafayette was greatly loved, but at the Cafe de la Monnaie,

on the rue de Roule, the sans-culottes burned him in effi gy. The Café de

la Porte St. Martin attracted quiet, respectable people out for an evening

stroll. As varieties of opinion were expressed, a man was judged by the

cafe of his choice. Rarely seen in cafes before, women began to follow the

example of the men and appeared in the evenings at the popular gather-

ing places. They were welcomed, as it was good for trade—the cafe trade,

which was to endure all upheavals and which persists until the present

day.

Paris was not alone in the development of cafe society. All the major

cities and towns of the country began to enjoy the companionship and the

stimulation of discussion in their favorite bistros. Owners were exposed

to certain occupational risks, as, on occasion, heated discussions led to

dishes and cutlery being hurled across the tables. Major topics under dis-

cussion in the news sheets and by sidewalk orators were the revolution,

184 Daily Life during the French Revolution

politics, members of the government, trade, colonies, fi nances, taxation,

and the huge defi cit.

FREEMASONRY

Imported from England in the early 1700s, Freemasonry had by the

end of the century reached 700 lodges, with 30,000 members, distributed

throughout all the major cities. Many of the revolutionaries were prominent

Freemasons. Louis-Philippe Orléans, cousin of the king, was Grand Mas-

ter, and others included Georges-Jacques Danton, Marie-Jean Condorcet,

and Jacques-Louis David. Individual Masons were very active within

the new society, some working through the press and literary societies

to make people aware of imminent political change. They were generally

well educated, often drawn from the wealthier families and an important

element, not unlike the salons, in spreading enlightenment ideas. Men of

all shades of opinion were recruited by the lodges. The “Committee of

Thirty,” which contained many prominent men, met mainly at the house

of Adrien du Port and put out pamphlets and models for petitions or

grievances and gave its support to political candidates. How much Free-

masonry infl uenced the course of the revolution remains to be clarifi ed,

however. The majority of members were bourgeois who approved of the

Masonic abstract symbol of equality; yet the organization’s hierarchical

structure confl icted with the egalitarian principles of the revolution.

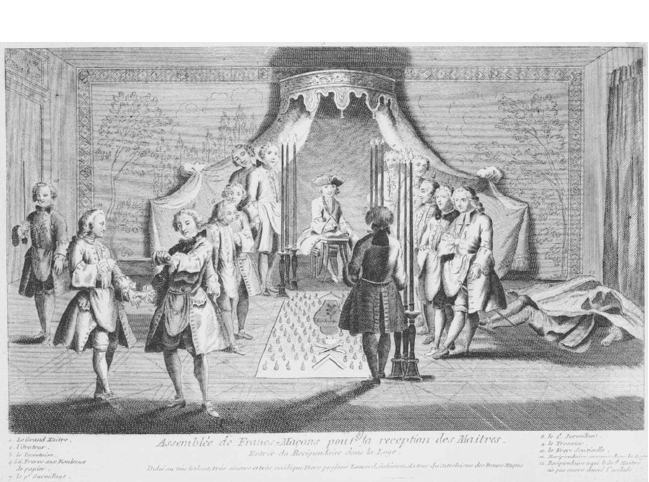

Reception of a Master Mason at a lodge meeting. Bibliothèque Nationale de

France.

Urban Life 185

In the army, too, Masons were to be found, especially among the offi cers.

Some claim that the election committees of the Estates-General consisted

mainly of Masons. Freemasons were in general considered suspect by the

Catholic Church, but although they preached a “natural” religion, they

did not necessarily look for the separation of the church from the state. In

general, Freemasonry attracted men who were interested in philanthropy,

fraternity, and friendship (being open to greater social mixing than other

old-regime groups), and in new political ideas.

The number of lodges refl ected the strength of the bourgeoisie and other

nonnoble groups of the Third Estate. Not all Masons became revolutionar-

ies, but the lodges were present in many revolutionary municipalities, and

their infl uence was palpable. Men who aspired to be politicians thus might

have found it advantageous to join and benefi t from the close personal ties

available among the “brothers.”

11

THE SANS-CULOTTES

The term “sans-culotte” referred to the men who did not wear the short

knee trousers (breeches) and silk stockings of the nobility and the upper

bourgeoisie but wore instead the long trousers of workers and shopkeep-

ers.

12

They were generally from the lower and often impoverished classes,

and “sans-culotte” was originally a derisive appellation. During the revo-

lution, the sans-culottes became a volatile collection of laborers in Paris

and other cities whose ranks soon included clerks, artisans, shopkeep-

ers, goldsmiths, bakers, and merchants. They were easily manipulated

by popular leaders such as Marat, Hébert, and Robespierre. The Jacobins

used the sans-culottes to control the streets of Paris and other cities and to

intimidate moderate members of the Assembly. The Committee of Public

Safety under Robespierre was adroit at using the discontented masses,

and in September 1793 a decree established a revolutionary sans-culotte

army. In October of that year, this army participated in severe violence

and brutality in Lyon against those it considered enemies of the state.

The sans-culottes were associated with popular politics, especially in the

Paris region, and were instrumental in the September massacres and in

the attacks on the Tuileries palace. In January 1794, the sans-culotte army,

having served its purpose, was disbanded by the Terror government.

Militant sans-culottes devoted much of their leisure to politics, even

while holding no offi cial post in their section of the city. Occasionally they

would visit the Jacobin club, but they generally divided their evenings

between the société sectionnaire and the General Assembly. In the section

they would be surrounded by friends in their own social milieu. They

wore the red bonnet, the carmagnole, and, in critical situations, carried their

pikes in hand. The pike was a powerful symbol of the people in arms. It

was not employed on the front against enemy armies but was extensively

used to quell disturbances at home. When the death penalty was decreed,

186 Daily Life during the French Revolution

on June 25, 1793, for hoarders and speculators, Jacques Roux said the sans-

culottes would execute the decree with their pikes.

13

On August 1, 1793,

the government authorized the municipalities to manufacture pikes on a

grand scale and to provide them to the citizens who lacked fi rearms.

Besides attending meetings of the sociétés sectionnaire s and the General

Assembly, sans-culottes also found time to socialize in cabarets, cafes, or

taverns, where they enjoyed singing patriotic songs.

The life of most sans-culottes was modest. Some bordered on the fringe

of the lower echelons of society and lived in a perpetual state of despera-

tion. It was not unknown for a family with three or more children to live in

one sparsely furnished room on an upper fl oor of a building.

Bread, the primary ingredient in the sans-culottes’ diet, was the princi-

pal source of nourishment for the poorer classes. The daily ration of the

average adult has been estimated at three pounds, that of a child one and

a half pounds. The sans-culottes demanded that their bread be of the same

quality as that of the rich—made with pure fl our. Under the old regime, a

family of four or fi ve would consume about 12 pounds a day at a cost of

three sous a pound. The budget for bread, then, could be as high as 36 sous

a day for a working man who made three livres a day, or about 60 sous.

The remainder of the wage might go to rent and a little wine. The poor

sans-culotte would return home to his attic after a day of backbreaking

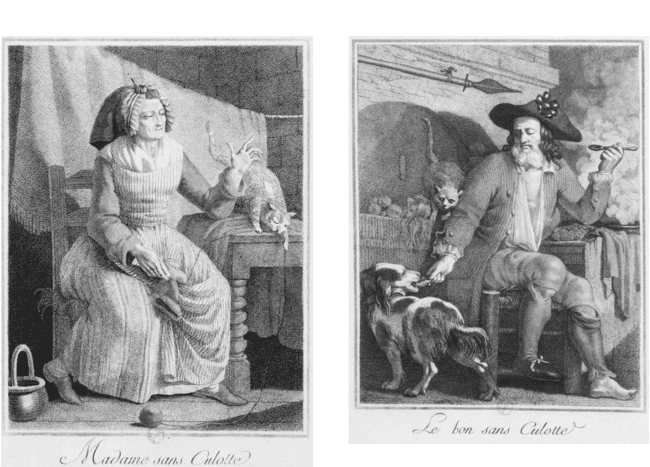

A sans-culotte as seen by other sans-culottes. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Urban Life 187

work, climb the stairs, and enter his one room to fi nd his children crying

or fi ghting and his wife perhaps pregnant and exhausted. He would sit

down at a rickety table on a half-broken chair and eat his dinner of stale

bread moistened by a little red wine before dropping onto a dirty cot, pull-

ing a torn blanket over him. Often not even a newspaper could relieve his

or his wife’s ennui because neither of them could read.

Knowledge of the events of the day and of the revolution in general was

gained at work sites or in city squares and, in small towns, by means of

public readers who expounded on the events described in the newspapers

to an audience of workmen gathered around for the occasion. In this way

people learned something of the words of Rousseau and the philosophers

and were inspired by the new ideas of liberty, justice, and equality. The

newspapers were purchased with individual donations of the workers.

For the man or woman who could read, there were ample posters, plac-

ards, and news sheets, as well as newspapers, to keep them informed. The

patriotic papers of the popular societies were also read in the evenings.

Angered by their poverty and by their concomitant hatred of wealth,

the sans-culottes insisted that it was the duty of the revolutionary govern-

ment to guarantee them the right to a decent existence. They demanded an

immediate increase in wages, along with fi xed prices, and an end to food

shortages. Further, they demanded that hoarders be punished and, most

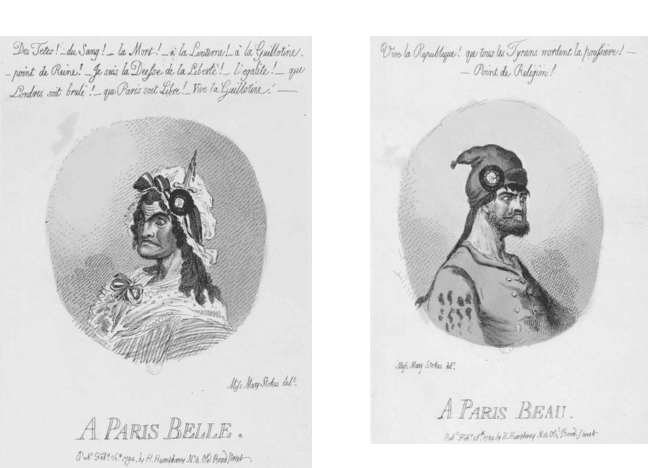

A sans-culotte as seen by the English, along with comments such as “long live the

guillotine!” Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

188 Daily Life during the French Revolution

important, that the existence of counterrevolutionaries be dealt with. In

terms of social ideals, the sans-culottes wanted laws to prevent extremes

of both wealth and property. They favored a democratic republic in which

the voice of the common man could be heard. Their ideology was not

unlike that of Thomas Paine, the English-American radical who argued

that the best form of government was the one that governed least. During

the revolution, they were represented by Père Duchesne, an artisan and

family man of the people whose name Hébert took for the name of his

radical, generally vulgar, newspaper.

NOTES

1. Garrioch, 18.

2. Ibid., 15ff.

3. Ibid., 28–29.

4. Sewell, 31–32.

5. Ibid., 118.

6. See Robiquet, 124.

7. Ibid., chapter 1, for more on the different districts in Paris.

8. Ibid., 4.

9. Ibid., 6.

10. Ibid., 16–19.

11. Ibid., 39–41.

12. Rudé (1988), 38; Hunt (1984), 199ff.

13. Soboul, 222ff.

14. Rose, 153. Roux was a popular parish priest of a Paris section and a member

of the Cordeliers. He advocated death for the hoarders.

12

Rural Life

Up to the time of the revolution, agriculture provided some three-quarters

of France’s gross national product. Only about a million inhabitants lived

in the large cities, and another 2 million populated the smaller towns. The

remaining 23 million or so lived in the countryside, either on farmsteads

or in small villages and hamlets around which they worked the land.

With no political power, the peasants were nevertheless heavily burdened

by taxes—on income for the king (taille), on land and on their crops for the

lord of the manor, and, through the dîme, for the church. In addition, there

were taxes on wine, cider, tobacco, and salt. If a peasant sold a piece of land,

he paid a sales tax. He also had to provide free labor about 10 days a year for

the crown, a system known as the corvée. He was forbidden to kill any game

animals, such as deer, boar, rabbits, and birds, even as they ate the crops and

his family was starving. When his sons reached manhood and were needed

on the farm, he could expect to see them forced into the army. Sometimes,

desperation led to protests and violence.

Taxes had always imposed a hardship on the peasants, but toward the

end of the eighteenth century peasants’ growing resentment began to be

aimed at the seigneurs, who often left the land in the hands of an agent

while they lived in town. Frequently, peasants did not know their lord

personally. Seigneuries could also be bought and sold, and wealthy bour-

geois sometimes purchased them, being more interested in making the

maximum profi t possible than in honoring traditional obligations. Such

changes were always a problem for the peasant, who then had to adjust to

new ways and to new lords who, too often, raised the rents.