Alfred DeMaris - Regression with Social Data, Modeling Continuous and Limited Response Variables

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a random sample of 100 observations on X and have the following sample statistics:

x

苶

5.8, s 4. Now since our sample is large, we know (from the CLT) that the sam-

pling distribution of X

苶

is approximately normal and centered over µ and has a

standard deviation of approximately 4/兹1

苶

0

苶

0

苶

, which equals .4. We therefore reason

as follows. We want a rejection rule for H

0

such that P(reject H

0

冟H

0

true) is only .05.

If H

0

is true, then µ is, at most, 5. This value is the null-hypothesized value of µ,

denoted µ

0

. Let’s suppose that H

0

is true and that µ is, in fact, 5. Then X

苶

has a nor-

mal distribution centered over 5, with a standard deviation of .4. We will want to

reject H

0

based on the distance of our sample mean from this value. In particular, if

our sample mean is too far above this value to be likely, given H

0

, we reject H

0

as

implausible. We choose a critical value of X

苶

, denoted X

苶

cv

, as our benchmark, so that

we reject H

0

if X

苶

X

苶

cv

. Since we want to take only a 5% chance of being wrong, we

want to choose a critical value of the sample mean such that P(X

苶

X

苶

cv

冟H

0

true) .05. That is, we want

P

冢

X

苶

s兾

兹

µ

n

苶

0

X

苶

s

c

兾

v

兹

n

苶

µ

0

冣

P

冢

Z

X

苶

s

c

兾

v

兹

n

苶

µ

0

冣

.05.

Since P(Z 1.645) .05, this implies that (X

苶

cv

5)/.4 must equal 1.645, or that X

苶

cv

must equal 5 1.645(.4) 5.658. Hence, X

苶

cv

5.658, and we reject H

0

if X

苶

5.658,

knowing that in doing so, there is only a 5% chance of rejecting an H

0

that is true.

The second way to proceed with the test is much simpler. We simply ask: What

is the probability of getting sample evidence at least as unfavorable to H

0

as we have

obtained if H

0

were actually true? This probability, called the p-value for the test,

represents the smallest

α

level at which H

0

could be rejected for a given test. The

p-value is therefore

P(sample evidence at least as unfavorable to H

0

as obtained 冟H

0

true)

P(X

苶

5.8 冟 H

0

true)

P

冢

X

苶

.

4

5

5.8

.4

5

冣

P(Z 2) .0228.

We then compare the p-value to the α level. If p α, we reject H

0

and accept H

1

. If

not, we fail to reject H

0

. In this case, if α is set at .05, then .0228 .05, so we reject

H

0

and conclude that the mean is greater than 5. By reporting the actual p-value

instead of simply whether H

0

is rejected, however, we indicate the strength of the

evidence against H

0

. In the current case, the evidence against H

0

is sufficient to reject

it but is not particularly strong. However, if p were, say, .001, the chances of getting

the current sample mean, if H

0

is true, would only be 1 in 1000, constituting sub-

stantially stronger evidence against the null.

APPENDIX: STATISTICAL REVIEW 35

c01.qxd 27.8.04 15:35 Page 35

Power of Hypothesis Tests. When H

0

is rejected, it is because the sample evidence is

considered very unlikely to occur were H

0

true. However, if we do not reject H

0

,

should we “accept” it as true? The answer is no. Generally, we do not accept H

0

despite failing to reject it. The primary reason for this is that failing to reject H

0

is

more a statement about our ability to detect departures from the null-hypothesized

value of the parameter (i.e., µ

0

) than about the true state of nature. That is, H

0

may be

false, but our test may not have enough power to detect it. The power of a test is the

probability that we will reject H

0

using the test when H

0

is false. As an example, con-

sider the fictitious sampling problem just discussed. Suppose that we had gotten a

sample mean of 5.4 instead of 5.8. Then the p-value for the test would have been

p P(X

苶

5.4 冟 H

0

true)

P

冢

Z

5.4

.4

5

冣

P(Z 1) .1587.

Employing conventional α levels, such as .05 or even .1, would still result in a failure

to reject H

0

. However, what if µ is really 5.2? Then, of course, the true sampling dis-

tribution of X

苶

is still normal with a standard deviation of .4, but it is centered over 5.2

instead of 5. However, we are operating under the assumption that µ is 5 (hypothesis

tests are always conducted under the assumption that H

0

is true); hence our critical

value of X

苶

is still 5.658. Let’s consider, then, the probability of making a correct deci-

sion (i.e., reject H

0

) in this case, using α .05:

P(correct decision 冟 µ 5.2) P(decision is to reject H

0

冟µ 5.2)

P(X

苶

5.658 冟 µ 5.2)

P

冢

Z

5.658

.4

5.2

冣

P(Z 1.145) .1261.

Thus, the power of the test under this condition is only .1261. That is, there is only

about a 13% chance of detecting that the null hypothesis is false in this case. If, on

the other hand, µ were really 6.2, the probability of correctly rejecting H

0

would be

P(X

苶

5.658 冟 µ 6.2) P

冢

Z

5.658

.4

6.2

冣

P(Z 1.355) .9123.

In this case, there is a greater than 90% chance that we will detect that H

0

is false.

As these extremes show, because we have no idea what the true value of the param-

eter is, it would be unwise to accept H

0

as true simply because we have failed to

reject it.

36 INTRODUCTION TO REGRESSION MODELING

c01.qxd 27.8.04 15:35 Page 36

More Complex Hypotheses. Hypotheses are always statements about the values of

one or more population parameters. Although this definition sounds restrictive, it’s

not. Even complex hypotheses can be distilled down to statements about parameter

values. For example, suppose I hypothesize that open disagreements in marriage

have a stronger positive effect on depressive symptomatology to the extent that indi-

viduals are less happily married. How do we boil this down into a statement about

a parameter? As we will see in Chapter 3, this hypothesis can be tested with the fol-

lowing regression model. If Y is a depressive symptomatology score, X

1

is open dis-

agreement, and X

2

is marital happiness, all continuous variables measured for a

sample of n cases, we can estimate the following regression model: E(Y) β

0

β

1

X

1

β

2

X

2

β

3

X

1

X

2

, where X

1

X

2

is the product of X

1

with X

2

. It turns out that our

research hypothesis can be restated in terms of one model parameter, β

3

. In particu-

lar, the research hypothesis is β

3

0.

NOTES

1. Finding the area, A, under a curve, f(x), involves the use of integral calculus.

The process of integration is, intuitively, as follows. To find the area under f(x)

between a and b, we divide the area into n equal-sized rectangles which are con-

tained completely within the area between f(x) and the X-axis. These are called

inscribed rectangles. The area of a rectangle is the base of the rectangle times

its height. The bases of each rectangle are the same: (b

a)/n. The height is the

point at which the rectangle first touches the curve from beneath. If the X-value

corresponding to that point is denoted x*, the height of the rectangle at that

point is f(x*). Hence, f(x*) times (b a)/n is the area of each inscribed rectan-

gle. To approximate the area under the curve, we sum up all of the rectangles

under f(x) from a to b. Although this approximation is quite crude, we can get

a better approximation by increasing n and repeating the procedure. This cre-

ates a more fine-grained subdivision of the area in question into narrower rec-

tangles, which fill in more of the gaps under the curve. Once again, we compute

the sum of the rectangles to refine our estimate of the area. If we repeat this pro-

cedure with ever-larger values of n, the resulting sum of the rectangles eventu-

ally converges to the area in question, as n tends to infinity.

2. Asymptotically refers to the behavior of a sample statistic as the sample size

tends to infinity. Asymptotic results usually provide very good guidelines for

what we can expect when n is large. How “large” n has to be for asymptotic

results to be approximately correct must be established on a case-by-case

basis, via simulation.

NOTES 37

c01.qxd 27.8.04 15:35 Page 37

CHAPTER 2

Simple Linear Regression

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

This chapter explicates the simple linear regression (SLR) model and its application to

social data analysis. I begin by discussing some real-data examples of linear relationships

between a dependent variable, Y, and an explanatory variable, X. It turns out that many

relationships between two continuous variables are approximately linear in nature, ren-

dering linear regression an ideal approach to analysis, at least as a beginning. I then intro-

duce the model formally and discuss its interpretation as well as the assumptions required

for estimation via ordinary least squares (OLS). This is followed by an explanation of

estimation using OLS, the most commonly used estimation technique. I then consider

several theoretical properties of the slope estimate necessary for inferences about the

relationship of X with Y. The chapter concludes with a discussion of model evaluation.

In particular, I consider various means of checking regression assumptions as well as

assessing the discriminatory power and empirical consistency of one’s model. This chap-

ter contains a fair amount of formal development of properties of the model. The reason

for this is that such developments readily generalize to the case of multiple regression but

are much simpler to do with only one predictor. This obviates the need to resort to matrix

algebra, as would be the case with several predictors in the model. Nevertheless, readers

with a limited math background will find it very helpful to review Sections I.P, II, and IV

of Appendix A in tandem with reading this chapter. There you will find a tutorial on func-

tions—in particular, linear functions—as well as tutorials on summation notation and

derivatives. These skills will enhance your assimilation of the material in this chapter.

LINEAR RELATIONSHIPS

Recall the introductory statistics data described in Chapter 1. One of the questions

frequently asked of an instructor in introductory statistics is: “How good does my

38

Regression with Social Data: Modeling Continuous and Limited Response Variables,

By Alfred DeMaris

ISBN 0-471-22337-9 Copyright © 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

c02.qxd 8/27/2004 2:47 PM Page 38

math background have to be to do well in the class?” One answer to the question

might be to examine how well math proficiency “predicts” or “explains” student

performance on the first exam. Intuitively, given that statistics is a form of applied

mathematics, one expects that students with stronger math skills should perform

better on the first exam than those whose skills are weaker. Two approximately con-

tinuous variables have been recorded for 213 students who took the first exam. The

first is their score on a math diagnostic quiz administered to all students on the first

day of class. The quiz consists of 45 questions, with the score being the number of

items answered correctly. Therefore, the score range is 0 to 45. This quiz roughly

gauges a student’s proficiency in math and is considered the explanatory variable,

X, in this example. (The explanatory variable is also referred to as the predictor,

the regressor, the independent variable, or the covariate.) The response variable

(also called the outcome, the criterion, or the dependent variable) is the score on

the first exam, which is administered during the sixth week of class. Its range is 0

to 102.

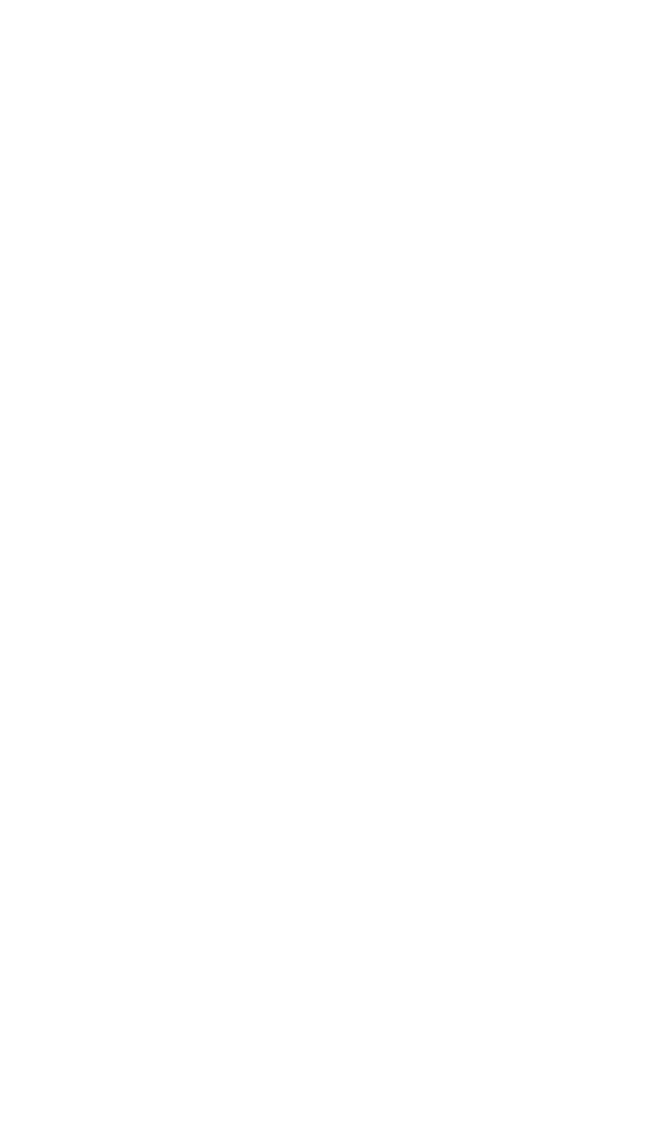

Figure 2.1 is a scatterplot of the (x,y) points for the 213 students, where X is

math diagnostic score and Y is score on exam 1. There is a fairly clear linear

upward trend in the scatter of points. Those with relatively low scores on the diag-

nostic (the minimum score was 28) tend to have relatively low scores on exam 1.

LINEAR RELATIONSHIPS 39

Figure 2.1 Scatterplot of Y (score on the first exam) against X (score on the math diagnostic) for 213

students in introductory statistics.

c02.qxd 8/27/2004 2:47 PM Page 39

As the diagnostic takes on higher values, the scatter of points migrates upward.

Those scoring in the middle 40s on the diagnostic, for example, have the highest

exam performance, on average. This upward trend is nicely represented by the

fitted line drawn through the center of the points. For now, the interpretation of

this line is that it is the best-fitting straight line through the scatter of points were

we to attempt to fit a straight line through them. (The meaning of best fitting is

explained in more detail below.)

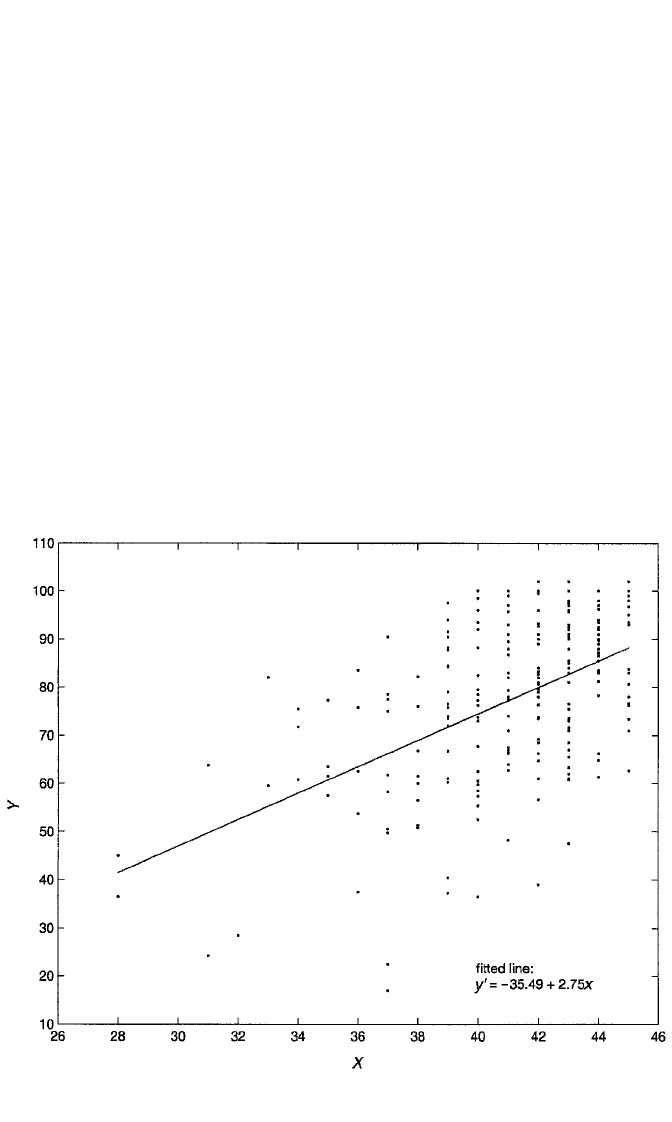

As another example we consider the couples dataset. Partners’ attitudes about gen-

der roles can sometimes be a source of friction for a couple, particularly when it

comes to sharing housework or other necessary tasks. Family sociologists have there-

fore studied the factors that affect whether partners’ attitudes are more traditional as

opposed to more modern. One such factor, of course, is education. One would expect

that couples with more years of schooling would tend to have more modern, or egal-

itarian, attitudes toward gender roles compared to others. A series of items asked in

the NSFH allows us to tap gender-role attitudes. Four were included in the couples

dataset and were asked of each partner of the couple. An example item asked for the

extent of agreement with the statement: “It’s much better for everyone if the man

earns the main living and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Response

choices ranged from “strongly agree,” coded 1, to “strongly disagree,” coded 5. The

other items were all similarly coded so that the high value represented the most mod-

ern, or egalitarian, response. To create a couple modernism score, I summed all eight

items for both partners. The resulting scale ranged from 8 to 40, with the highest score

representing couples with the most egalitarian attitude. Figure 2.2 shows a scatterplot

of Y couple gender-role modernism plotted against male partner’s years of school-

ing completed (X) for the 416 couples in the dataset. The linear trend is again evident

in the scatter of points, as highlighted by the fitted line.

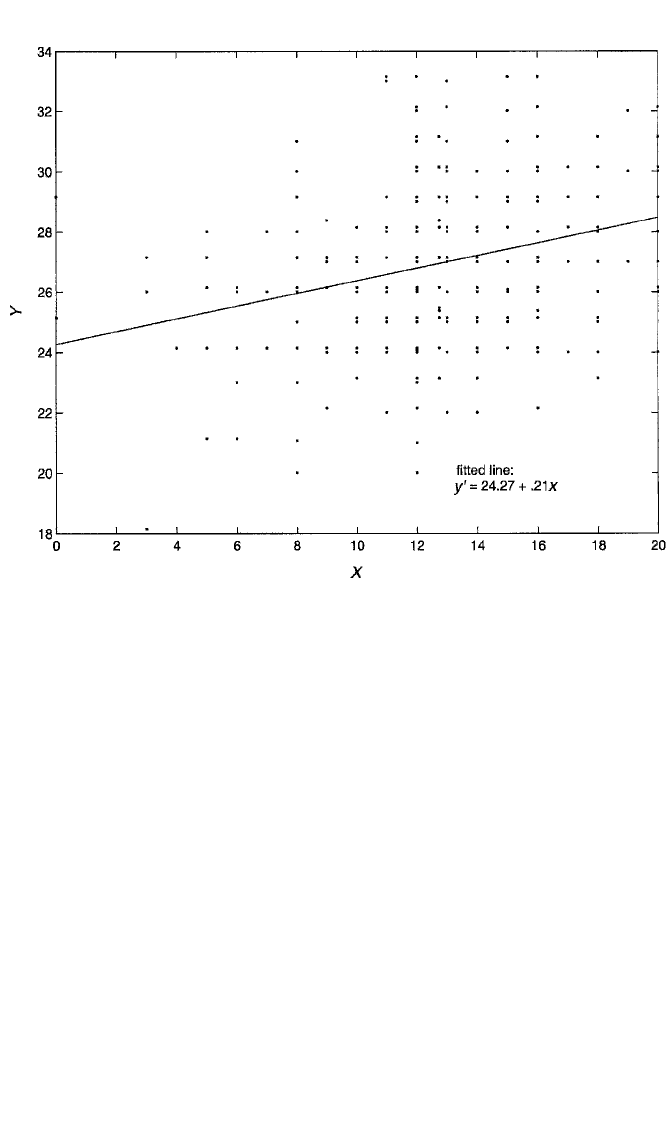

As a third example, I draw on the GSS98 dataset. Among the questions asked of

1515 adult respondents in this survey was one about sexual activity. In particular,

the question was: “About how often did you have sex during the last 12 months?”

Response choices were coded 0 for “not at all,” 1 for “once or twice,” 2 for “about once

a month,” 3 for “2 or 3 times a month,” 4 for “about once a week,” 5 for “2 or 3 times

a week,” and 6 for “more than 3 times a week.” Although this variable is not truly con-

tinuous, it is ordinal, and has enough levels—five or more is enough—to be treated as

“approximately” continuous. This approximation is especially tenable if n is large, as

it is for these data, and if the distribution of the variable is not too skewed. Regarding

the latter condition, the percent of people giving each response—0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6—

is 22.2, 7.5, 11.3,15.4, 18.3, 19.7, and 5.4, respectively. This represents an acceptable

level of skew.

What predicts sexual activity? Several obvious determinants come to mind, such

as age and health. But what about frequenting bars? There are several reasons why

those who frequent bars might be more sexually active than others. Some reasons

have to do with the selectivity of bar clientele and do not implicate bars as a cause of

sexual activity per se. For example, sexually active couples often go to bars or night-

clubs first before engaging in intimate activity. Also, those who go to bars more often

are most likely younger and possibly looking for sexual partners to begin with.

40 SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION

c02.qxd 8/27/2004 2:47 PM Page 40

Hence, it would not be surprising that bar clientele would tend to be more sexually

active than others. On the other hand, frequenting bars might also play a causal role

in enhancing sexual activity. First, regardless of whether one is looking for a sexual

partner, bars tend to enhance one’s opportunities for meeting potential sex partners.

“Singles” bars are especially likely to draw a clientele that is in the “market” for sex,

enhancing one’s potential pool of willing partners. Then, too, the atmosphere of bars

is especially conducive to romantic and/or sexual arousal. Alcohol is being freely con-

sumed, the lights are usually dimmed, and erotic music is often playing in the back-

ground. For any of the foregoing reasons, I would expect a positive relationship

between going to bars and having sex. Fortunately, it’s easy to explore this hypothe-

sis, since the GSS also asked respondents: “How often do you go to a bar or tavern?”

with responses ranging from 1 for “never” to 7 for “almost every day.” An examina-

tion of the distribution of this variable reveals that it is somewhat more skewed than

sexual frequency (e.g., 49.2% of respondents never go to bars) but still at an accept-

able level of skew for regression.

A scatterplot of Y frequency of having sex in the past year against X frequency

of going to bars is shown in Figure 2.3. This scatterplot is somewhat deceptive. At first

glance there is no visible linear trend. However the best-fitting line through these

points does, indeed, have a slight upward slope, going from left to right. This indicates

LINEAR RELATIONSHIPS 41

Figure 2.2 Scatterplot of Y (couple modernism score) against X (male’s years of schooling) for 416 cou-

ples from the National Survey of Families and Households, 1987–1988.

c02.qxd 8/27/2004 2:47 PM Page 41

that there is a positive relationship between X and Y. We will see (below) that this pos-

itive trend is also statistically significant.

SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION MODEL

The idea behind regression is quite simple. Again using the relationship in Figure 2.1

as a substantive referent, we imagine that a linear relationship between, say, math

diagnostic score and score on the first exam characterizes the population from which

the student sample was drawn. (In that this sample was not randomly drawn from any

population, we have to imagine a hypothetical population of introductory statistics

students that might be generated via repeated sampling.) That is, a straight line char-

acterizes the relationship between math diagnostic score and first exam performance

in the population, much as the fitted line in Figure 2.1 characterizes the relationship

between these variables in the sample. Our task is, essentially, to find that line. The

line is of the form β

0

β

1

X, where β

0

is the Y-intercept of the line and β

1

is the slope

of the line. That is, we want to estimate the parameters (β

0

and β

1

) of that line, rep-

resenting the “regression” of Y on X, and use them to further understand the relation-

ship between the variables. The simple linear regression model is therefore nothing

more than the equation for this line, plus a few additional assumptions.

42 SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION

Figure 2.3 Scatterplot of Y (frequency of having sex in past year) against X (frequency of going to bars)

for 1515 respondents from the General Social Survey, 1998.

c02.qxd 8/27/2004 2:47 PM Page 42

Regression Assumptions

In particular, we assume (1) that the Y

i

for i 1,2,...,n represent n independently

sampled observations on a response variable, Y. We further assume (2) that Y for

each observation has been “generated” (say, by nature) by a linear function applied

to that case’s value on an explanatory variable, X. The model for the ith observation

on Y is therefore

Y

i

β

0

β

1

X

i

ε

i

. (2.1)

It is assumed (3) that both Y and X are continuous variables. This is not to be taken

too literally. As indicated above, regression is acceptable as long as Y and X are

approximately continuous. A rule of thumb for approximately continuous to hold is

that the variable should be at least ordinal and have at least five different levels, pro-

vided that n is large and that the distribution of the variable is not too skewed. In fact,

X can also be dichotomous. This type of predictor, called a dummy variable, is intro-

duced in Chapter 4 (as well as in Exercises 2.26 to 2.28). Moreover, Y can be

dichotomous, although some problems emerge when using linear regression in such

a case (more on this in Chapter 7). It is assumed (4) that X is fixed over repeated

sampling. That is, the assumption is that observations on Y are sampled from sub-

populations with values of X that are known ahead of time (later we will see that this

assumption can be relaxed under certain conditions). It is also assumed (5) that X is

measured with only negligible error (Myers, 1986).

The ε

i

’s, called the equation errors or disturbances, represent all influences on Y

other than X. If Y were an exact linear function of X, that is, if Y

i

were exactly equal to

β

0

β

1

X

i

, called the structural part of the model, and all points lay right on the regres-

sion line, there would be no error term. However, this would represent a deterministic

relationship between Y and X. That is, Y would be determined completely by X, such

that increasing X by 1 unit would automatically increase Y by β

1

units. Such relation-

ships are rarely—no, never—observed in the social sciences. Instead, social data tend

to be characterized by probabilistic relationships in which increasing X increases the

likelihood that Y will increase (or decrease, if β

1

0) (Lieberson, 1997), but doesn’t

guarantee it. The error term represents this random or stochastic component of the

model. Manipulating equation (2.1), we see that ε

i

Y

i

(β

0

β

1

X

i

). That is, the

errors represent the departures of Y-values from the line β

0

β

1

X

i

. Typically, for any

particular value x

i

of X

i

, there will be several different Y

i

values among the observations

with that x

i

. Hence, there will be several different ε

i

at any particular value of X.

The errors are also subject to some assumptions. It is assumed (6) that at each

value of X, the mean of the errors is zero. The assumption is that the positive and neg-

ative errors tend to balance each other out, so that overall, the mean of the errors at

any given X is zero. Additionally, it is assumed (7) that the errors all have the same

variance at each X-value; this variance is denoted by σ

2

. It is also assumed (8) that the

errors are uncorrelated with each other. If the observations have been sampled inde-

pendently and the data are cross-sectional, this is typically the case. Finally, it is

assumed (9) that the errors are normally distributed in the population. The proper way

SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION MODEL 43

c02.qxd 8/27/2004 2:47 PM Page 43

to think about the regression assumptions is not: “Okay, let’s assume that . . .” and

then proceed with a regression analysis. Rather, the proper perspective is: “If the fol-

lowing assumptions hold, it makes sense to estimate a linear regression model.”

Below I discuss ways of assessing whether these assumptions are reasonable.

Interpreting the Regression Equation

Taking expectations of both sides of equation (2.1), we have

E(Y

i

) E(β

0

β

1

X

i

ε

i

)

E(β

0

β

1

X

i

) E(ε

i

)

β

0

β

1

X

i

0

β

0

β

1

X

i

. (2.2)

(Note that the β’s and X

i

are constants at any particular X

i

, and the mean of a con-

stant is just that constant.) In other words, according to the model E(Y

i

), the mean of

the Y

i

(more properly, the conditional mean of the Y

i

, since this mean is conditional

on the value of X) is a linear function of the X

i

. That is, the mean of the Y

i

at any

given X

i

is simply a point on the regression line. Hence, using regression modeling

assumes, at the outset, that the means of the dependent variable at each X-value lie

on a straight line. To understand how to interpret β

0

and β

1

, we manipulate equation

(2.2) so as to isolate either parameter. For example, if X

i

0, we have

E(Y

i

X

i

0) β

0

β

1

(0) β

0

.

Hence, β

0

, the intercept, is the mean of Y when X equals zero. To isolate β

1

, we con-

sider the difference in the mean of Y for observations that are 1 unit apart on X. That

is, we compute the difference E(Y

i

x

i

1) E(Y

i

x

i

). Notice that this is the differ-

ence in E(Y) for a unit difference in X, regardless of the level of X at which that unit

difference occurs. We have

E(Y

i

x

i

1) E(Y

i

x

i

) β

0

β

1

(x

i

1) [β

0

β

1

x

i

]

β

0

β

1

x

i

β

1

β

0

β

1

x

i

β

1

.

In other words, β

1

represents the difference in the mean of Y in the population for

those who are a unit apart on X. If X is presumed to have a causal effect on Y, β

1

might be interpreted as the expected change in Y for a unit increase in X. In either

case, I will refer to E(Y

i

x

i

1) E(Y

i

x

i

) as the unit impact of X in the model. The

unit impact of X in any regression model—whether linear or not—can always be

found by computing E(Y

i

x

i

1) – E(Y

i

x

i

) according to the model.

The interpretation of β

1

can also be elucidated by taking the first derivative of

E(Y

i

) with respect to X:

d

d

X

i

[E(Y

i

)]

d

d

X

i

[β

0

+β

1

X

i

] β

1

.

44 SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION

c02.qxd 8/27/2004 2:47 PM Page 44