Adams, Kyle: A New Theory of Chromaticism from the Late Sixteenth to the Early Eighteenth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

255

Journal of Music Theory 53:2, Fall 2009

DOI 10.1215/00222909-2010-004 © 2010 by Yale University

A New Theory of Chromaticism

from the Late Sixteenth to

the Early Eighteenth Century

Kyle Adams

Abstract This article is intended as a solution to a perceived problem with existing theories of pretonal chro-

matic music: Many modern theories of this repertoire have made anachronistic uses of models from major/

minor tonality, and contemporaneous theories were not broad enough to adequately represent the phenomena

that, to my own—and, I believe, many other modern listeners’—ears, gave chromatic music its unique sound.

Both groups of theories missed the mark by treating all chromatic events in this repertoire equally. This article

therefore begins by suggesting that, just as in tonal music, chromaticism in this period comprises many different

phenomena. I therefore provide a model for separating chromatic tones according to their structural function and

an analytical method for reducing chromatic works to their diatonic foundations. I present examples of each of

the chromatic techniques that I describe and give detailed criteria for identifying each technique. In doing so, I

provide a new vocabulary by which scholars and analysts can model the way in which they hear chromatic music

from this period.

Introduction

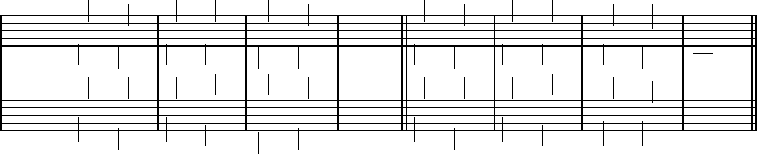

the theory presented in this article is best introduced by an analogy to

tonal music. I present the two progressions given in Example 1 in order to

explain their relevance to the present subject. Each example uses the same

chromatic sonority, the B≤ major chord in the second half of m. 2, in different

ways. In Example 1a, the chromatic sonority is folded into the overall D-major

tonality and is understood as a substitute for a diatonic sonority. An analyst

would therefore label it ≤VI, in order to indicate its origins in the diatonic vi

chord. In Example 1b, the same chord functions as a chromatic pivot to usher

in a new tonality and would likely receive two labels, ≤VI in D and IV in F, to

indicate its dual function. The point of this example is twofold: First, our per-

ception of the function of the chromatic sonority is dependent on context.

This article is a condensed version of the theory presented in my dissertation (Adams 2006), which I

encourage readers to consult for a more comprehensive treatment of this topic, including a complete list

of the repertoire I examined in my research. I express my gratitude to William Rothstein, Ruth DeFord,

David Gagne, Nancy Nguyen-Adams, and Linda Pearse, as well as the anonymous readers, for their help

in developing and focusing this article.

256

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

The listener understands the chord only in light of the following sonorities,

since both progressions begin the same way.

1

Second, tonal music theorists are

comfortable with the same chromatic sonority having different functions in

different contexts, with the use of different labels for such sonorities, and with

the existence of different varieties of chromaticism in general.

adams_01a-b (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:12 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

²

²

²

²

‡

‡

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

−

−

¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

−

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

−

−

¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

¦

¦

¦

ð

ð

ð

ð−

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

¦

¦

¦

!

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 1a-b

(a) (b)

Example 1. Chromaticism in two tonal progressions, (a) and (b)

I bring up these two points because, while tonal theory seems to be

completely at ease with these concepts, pretonal theory does not seem to be.

Part of what has hindered theorists’ understanding of chromaticism in early

music is the insistence on a single conception of chromaticism, from theorists

both of this time period and of our own. Thus, the present article begins from

the premise that chromatic sonorities can have different functions in pretonal

music,

2

just as they can in tonal music, and that context can help to determine

the type of chromaticism at play in a given passage.

Background

Analysts approaching chromatic music from this period have suffered from an

overreliance on a single theoretical model.

3

Theorists from the period under

discussion subscribed to one of two views of the chromatic genus. Those

adhering to the relative conception considered the chromatic genus to reside

in the use of a given interval or intervallic progression, typically the chromatic

semitone.

4

This has also been the conception put forth by modern “historicist”

1 In fact, the very existence of chromaticism in this passage

is contextual. Out of context, the B≤ major chord is diatonic,

unlike, for example, an augmented sixth chord, which can-

not be taken from any diatonic scale and is therefore chro-

matic regardless of its context.

2 I am aware of the strong differences of opinion on the

appropriate term for music from this period. Some scholars

consider “pretonal” overly teleological, and others consider

“early music” overly vague. Since this article clearly delin-

eates the historical period with which it deals, I use both

terms interchangeably to describe music from that period

and do not enter into the controversy over terminology.

3 What follows is a highly condensed version of my sum-

mary of earlier conceptions of chromaticism in Adams 2007,

15–25, and of my explication of modern conceptions of early

chromaticism, as well as problems with both conceptions,

in Adams 2006, 53–79. Space does not permit me to thor-

oughly explore those subjects here, but I direct readers to

those works for a much more comprehensive treatment.

4 These include Vicentino ([1555] 1996), Lusitano ([1561]

1989), Burmeister ([1606] 1993), and Printz (1679). Even

Rameau ([1737] 1966) describes the origin of “this new

genus of Harmony” in the semitone produced by the over-

tones of two notes a third apart (171).

257

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

scholars,

5

notably Margaret Bent and James haar, both of whom emphasize the

melodic nature of chromaticism in early music, especially the use of melodies

involving the chromatic semitone.

6

On the other hand, theorists subscribing

to the absolute conception of chromaticism define the chromatic genus by its

use of pitches outside of an established diatonic collection.

7

In the sixteenth

century, this collection was typically the gamut of musica recta, but moving

into the eighteenth century, it was conceived of as whatever diatonic scale (in

the modern sense) was operational in a given passage. Since this conception

of chromaticism is basically the one used in tonal theory, it is not surprising

that the more “presentist” analyses of early chromaticism use it as a starting

point. Presentist approaches take various forms, and most have focused on a

single work, the Prologue to Orlando di Lasso’s Prophetiae Sibyllarum (1560).

Among the approaches to this work are William Mitchell’s (1970) Schenker-

ian analysis, and Karol Berger’s (1976) and William Eastman Lake’s (1991)

hierarchical arrangements of roman numerals. All three attempt to explain

Lasso’s chromaticism much as one would in a tonal piece, by describing the

chromatic sonorities as they relate to diatonic sonorities.

In brief, no single one of these approaches proves satisfactory for mod-

eling the wealth of works, passages, and techniques from this period that can

reasonably be called “chromatic.” reliance on the chromatic semitone creates

two problems. First, it does not account for all of the intentionally chromatic

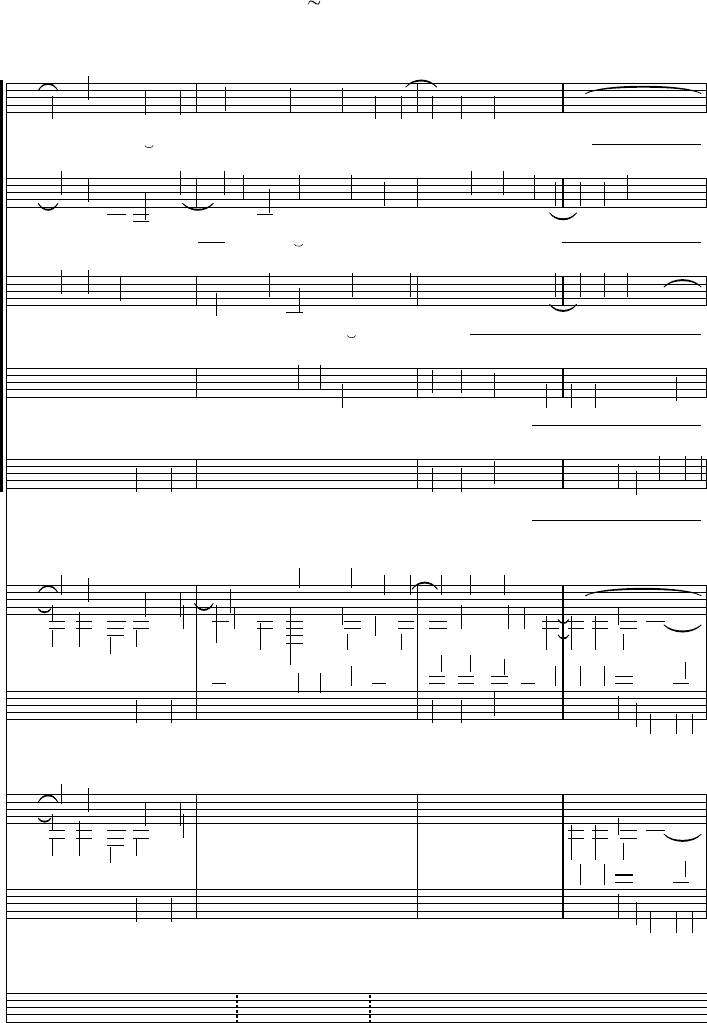

passages from this period. Example 2 is from Lasso’s Sibylla Cimmeria. Lasso’s

own text to the Prologue of this work tells us that it is intended to be chro-

matic, and yet this brief succession of chords, striking as it is, contains no

chromatic semitones.

Second, one also finds passages in which notated chromatic semitones

occur in completely diatonic progressions. The best known of these comes

from Luca Marenzio’s madrigal O voi che sospirate a miglior note (1581), in which

a dense jumble of notated chromatic semitones can be renotated to reveal a

simple chain of descending fifths.

8

5 For explanations of the historicist and presentist posi-

tions, see Christensen (1993).

6 Haar’s view (1977, 392) is more temperate than Bent’s,

who asserts that “for Zarlino, only melodic progressions

that sound chromatic because they use the chromatic semi-

tone qualified as chromatic” (2002, 129).

7 These include Zarlino ([1558] 1968), Bottrigari ([1594]

1962), Morley ([1597] 1973), Mersenne ([1627] 2003), and

Werckmeister ([1707] 1970).

8 This passage is discussed in Fétis 1879.

adams_02 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

‡

‡

þ

þ

þ

þ

ý

²

²

²

Ð

Ð

²

²

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

þ

ý

!

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 2

Example 2. Lasso, Sibylla Cimmeria

258

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

The presentist, “absolute” conception of chromaticism likewise has its

weaknesses. Both the Schenkerian and roman-numeral analyses suffer from

attempts to fit Lasso’s prologue into an overall “tonality” of G. Mitchell ignores

surface features of the music that contradict his Schenkerian approach, while

Berger uses roman numerals without regard for the hierarchy of functional

relationships that such usage traditionally implies. Thus, in Berger’s chart of

roman numerals, one finds progressions such as V–VI–I without any explana-

tory note.

The present theory does not pretend to solve every problem in the analysis

of early chromatic music. however, as I stated above, I begin from the premise

that chromatic sonorities in early music can have different functions in different

contexts and that “chromaticism” as applied to early music does not describe a

single technique any more than it does in tonal music. I assert that not all chro-

matic tones exist for the same reason or at the same level of structure and that

different levels of these tones can be separated from one another according to

their structural functions. On one hand, I approach the music from a present-

ist point of view by attempting to describe my own—and, I believe, the typical

modern listener’s—perception of chromatic music.

9

I use historical texts as

informants but do not try to divine the composer’s conception of chromatic

music or to describe the sixteenth- or seventeenth-century listener’s perception

of it. On the other hand, I take a historicist point of view by approaching the

music without using the Procrustean bed of major/minor tonality. I attempt

to provide an accurate model for this repertoire by using principles derived

from the musical texts. My theory therefore tries to converge the presentist and

historicist positions by using both the concepts available to earlier theorists and

appropriate concepts from the present day to describe as accurately as possible

the objective phenomena that, to a modern listener, distinguish this repertoire

from other types of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century music.

Repertoire and time period

The theory that follows is based on a study of all available chromatic music

published roughly within the time period 1555–1737. This period is demar-

cated by the publication of Nicola Vicentino’s Ancient Music Adapted to Mod-

ern Practice and Jean-Philippe rameau’s Génération harmonique, which were,

respectively, the first and last works after classical antiquity both to discuss the

chromatic as a separate genus and to apply its use to contemporary music.

10

Works from this time period were included in the study if they fell into one or

more of the following classes:

9 I use the term “listener” to mean someone familiar with

the norms of Western art music.

10 Even the use of these fairly objective criteria to choose

a time period led to some absurdities: Can one really say

that Bach used a different variety of chromaticism after

1737 than he used before? Nevertheless, it was necessary

to have some boundary dates for the musical examples in

order to keep their numbers from becoming unmanageably

large.

259

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

Pieces whose title or text contains the word • chromatic, or some var-

iation of it. This category includes pieces identified as durezze, a

seventeenth-century keyboard genre characterized by a multitude of

harsh dissonances and unusually resolving suspensions.

Pieces with features that conformed to contemporaneous or earlier

•

theoretical conceptions of chromaticism, including (a) conspicuous

uses of the ancient Greek chromatic tetrachord (two semitones and a

minor third);

11

(b) widespread use of “black-key” (i.e., chromatically

altered) tones;

12

and (c) employment of the chromatic fourth (i.e., six

consecutive semitones filling the interval of a perfect fourth).

13

Pieces featuring widespread use of what a modern musician would •

call chromatic figuration.

Pieces from two tangentially related categories: those whose titles con-

•

tain the term “enharmonic” (as opposed to “chromatic”), and others

that very clearly make use of enharmonic relationships to juxtapose

distantly related sonorities; and “labyrinth” or “circle” pieces that,

through sequential repetition, travel to very distant tonalities and

eventually return to their starting tonalities.

I. Explanation of the theory

Components of the theory and definitions

This theory has two components: a theoretical model for classifying differ-

ent types of chromaticism and an analytical method that uses that model

to separate different types of chromatic tones according to their structural

functions.

Definitions. This theory uses the following definitions:

(1) Tonal system: A collection of pitch classes equivalent to the modern

diatonic scale but without any hierarchy among them. The tonal

system is named for the number of accidentals it contains; thus,

the one-sharp system would be equivalent to the modern G-major

scale but without a center on G. When a passage of music uses only

tones from a single tonal system, that system is said to govern the

passage.

14

(2) Diatonic: A diatonic tone is one that belongs to the governing tonal

system. A diatonic sonority is one that contains only such tones.

11 In this article, “chromatic tetrachord” always refers to

this melodic succession.

12 Bottrigari [1594] 1962 defines the chromatic genus as the

use of these tones (see 33–34).

13 In my research, I examined more than 1,400 examples

of the chromatic fourth. Since my dissertation devotes an

entire chapter to my analytical findings regarding this pro-

gression, examples containing it are not treated in this

article.

14 See Appendix A for a further discussion of my concep-

tion of tonal system.

260

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

(3) Chromatic: A chromatic tone is one that falls outside the governing

tonal system. A chromatic sonority is one that contains any such

tones.

(4) Essential chromaticism: The use of chromatic alterations to correct

an unacceptable sonority in a given repertoire. In the period under

consideration here, such alterations typically correct the intervals

excluded by the mi contra fa prohibition, that is, imperfect unisons,

fourths, fifths, and octaves, whether vertical or horizontal.

15

(5) Nonessential chromaticism: The use of either of the following two

types of chromatic alterations:

(a) Type A: Alterations that serve to correct sonorities that are

contextually incorrect. For example, in the sixteenth century,

a minor sixth is by no means prohibited but can become so if

it progresses to an octave at a final cadence. Typically, type A

alterations involve either cadential leading tones or Picardy

thirds (which themselves become less structurally important

throughout this period);

16

however, they may also be used to

preserve strict imitation of a motive.

17

(b) Type B: Alterations that serve only expressive purposes. They

may exist for affective or text-painting reasons but do not cor-

rect any type of incorrect sonority.

Figure 1. A continuum of chromaticism

The theoretical model: A continuum of chromaticism. Figure 1 presents a con-

tinuum containing various categories of chromaticism. The techniques in Fig-

ure 1 are listed in order of increasing chromaticism. The top of the continuum

is divided into three large categories. Diatonicism refers to passages governed

by a single tonal system. Indirect chromaticism refers to passages in which any

two successive sonorities belong to a single tonal system but the passage con-

taining them does not. Direct chromaticism refers to passages containing two

successive sonorities that do not belong to the same tonal system. Underneath

the continuum are several smaller-scale techniques. At the two ends are pure

15 The status of chromatic alterations that correct cross-

relations depends on the composer and time period, since

cross-relations generally became more acceptable as this

period went on.

16 Following the distinctions made in Berger 2004, 137, I

consider cadences to be more structurally significant than

other places in which a composer or performer might choose

to create directed motion via a chromatic inflection.

17 See Appendix B for further discussion of the terms

essential and nonessential.

Indirect Direct

Diatonicism chromaticism chromaticism

Pure Nonessential Essential Juxtaposed Suspended

diatonicism chromaticism chromaticism diatonicism diatonicism

261

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

diatonicism, which refers to any passage that uses only diatonic sonorities, and

suspended diatonicism, which consists of any passage for which it is impossible to

determine the governing tonal system. The latter usually occurs because the

accumulation of semitones makes it impossible to arrive at a diatonic basis for

the passage. These endpoints are what Carl Dahlhaus, following Max Weber,

refers to as ideal types;

18

that is, they are categories that exist in principle

but may have no occurrences in actual music. Pure diatonicism, for example,

rarely exists for long spans of time, despite the fact that a single renaissance

work may be notated without accidentals from beginning to end. If unnotated

musica ficta is considered to be a given feature of the musical surface, as I argue

it should (see Appendix B), then there is hardly a renaissance work that does

not exhibit chromaticism as I have defined it. Likewise, although many musi-

cal examples verge on suspended diatonicism, this ideal type does not seem

to exist in practice. Every passage I have examined, no matter how densely

chromatic, has features that give it some diatonic context.

Between pure diatonicism and suspended diatonicism are three other

chromatic techniques identifiable in music from this period. Nonessential chro-

maticism has already been defined. Note that it appears under the general

category of diatonicism because nonessential chromatic tones are alterations

of diatonic tones and can be removed to reveal a passage of pure diaton icism.

Essential chromaticism has also already been defined, and it is the first type of

chromaticism along the continuum. Essential chromatic tones will nearly

always signal a move into a tonal system in which they are diatonic. Unlike

true diatonic tones, however, they are chromatic in relation to the system that

came before. Juxtaposed diatonicism consists of the placement of two different

tonal systems alongside one another using direct chromaticism.

Figure 1 is not a line in which every chromatic work has a position rela-

tive to every other and one can plot precisely the relative degree of chromati-

cism of any work. The categories and techniques of chromaticism represented

on it can coexist in the same work, or even in a single passage. Nor is the

continuum the most accurate possible graphic representation of the catego-

ries it contains; for example, nonessential chromaticism can exist within jux-

taposed diatonicism. Nonetheless, it is a useful way to schematize chromatic

techniques in the repertoire under consideration.

The analytical method: Diatonic reduction

Diatonic reduction is a method of distinguishing among various levels of chro-

maticism in a given passage. It consists of the removal of nonessential chro-

matic alterations to reveal the tonal system(s) underlying a given passage.

18 Weber, as quoted in Gossett 1989, describes an “ideal

type” as follows: “An ideal type is formed . . . by the synthe-

sis of a great many diffuse, discrete, more or less present

and occasionally absent concrete individual phenomena,

which are arranged according to those one-sidedly empha-

sized viewpoints into a unified analytical construct. In its

conceptual purity, this mental construct cannot be found

empirically anywhere in reality” (51).

262

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

I explain diatonic reduction through reference to an example. The guidelines

for creating a diatonic reduction are also given in list form in Appendix C.

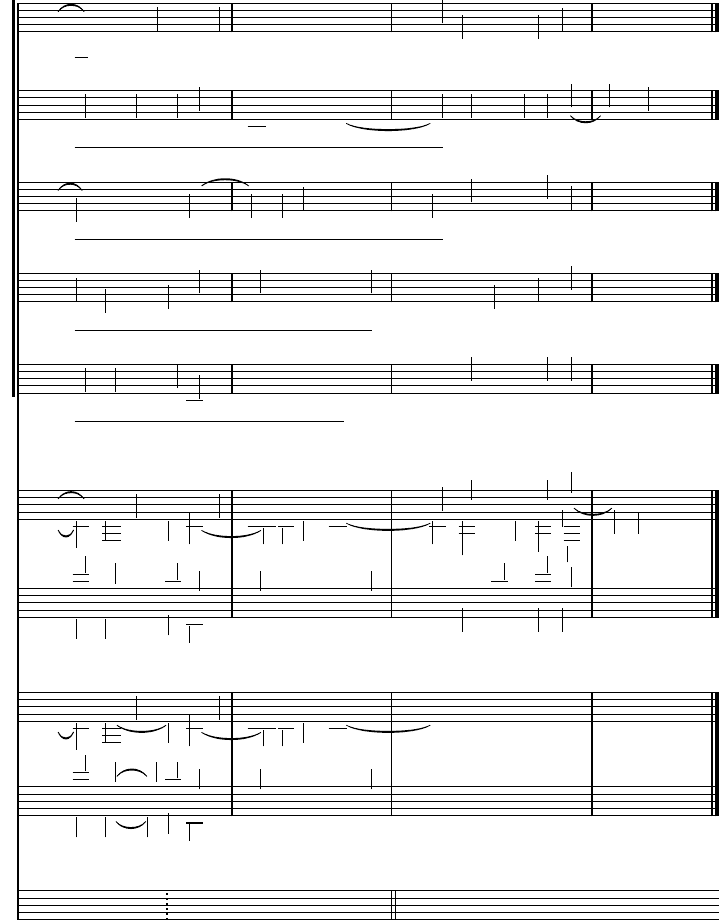

Example 3 presents a diatonic reduction of the last eight measures of

Carlo Gesualdo’s Ma tu, cagion, the second part of Poichè l’avida sete, from the

fifth book of madrigals. Because my focus at this stage is on the meaning of the

analytical notation and not on the composition itself, I do not make extensive

arguments for the analytical choices the notation communicates.

A typical diatonic reduction, like the one in Example 3, has four com-

ponents. The top system reproduces the score. The lowest staff, labeled “tonal

systems,” tracks the governing tonal system at each moment in the music. The

ways in which key signatures and barlines are used on this staff are explained

below. Between these two systems are two successive stages of reduction. Stage 1

of the reduction reproduces the score without any type B alterations (those

that exist only for expressive purposes). Stage 2 reduces stage 1 even further

by removing type A alterations (those that correct structurally incorrect sonor-

ities). If a given passage contains only one type of nonessential alteration, or

none at all, either stage 1 or 2 or both may be omitted. The lowest system of

music in the reduction will always contain the diatonic framework upon which

a given chromatic passage is built, and the “tonal system” staff below that will

show its governing tonal system.

Example 3 may be read as follows: The passage begins in the two-sharp

system, as shown on the lowest staff. Tonal systems on this staff will always

be notated as modern key signatures,

19

with two exceptions: Passages of sus-

pended diatonicism will have no key signature, and passages in the natural sys-

tem will be written with a signature of BΩ.

20

The two-sharp signature means that

any tones in the original passage not belonging to the two-sharp system are

chromatic alterations and have been removed either in stage 1 or in stage 2

of the reduction. By comparing the score with the stages of reduction, readers

can see which types of chromatic alterations have been removed; thus, in the

first measure of the example, the soprano D≥ has been removed in stage 2 of

the reduction since it is a type A alteration, providing directed motion to the

following sonority.

On the “tonal system” staff, changes of system brought about by indirect

chromaticism are represented with dotted barlines, followed by whatever acci-

dental has been added, or a natural sign in the position where an accidental

has been removed. Any accidentals before the dotted barline are assumed to

still be in effect after it. In the middle of m. 28, CΩ is introduced via indirect

chromaticism (the leaps from G to C in alto and tenor 1). The music there-

fore briefly moves into the one-sharp system. At the end of the bar, the pas-

sage returns to the two-sharp system, again via indirect chromaticism. (C≥ is

19 These signatures are not intended to be equivalent to

modern key signatures; they represent only the sharps or

flats used in the tonal system, which I notate in the tradi-

tional positions for clarity.

20 I chose BΩ mainly because of its position in the middle of

the staff and because of the special significance of the BΩ/

B≤ relationship in early music.

263

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

adams_03 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 2 pages

+

+

Š

Š

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

²

²

Ł²

Ł

Ł

þ²

Ðý²

þ

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

²

²

²

þ

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

²

²

²

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ð

Ð

ð²

ÿ

Ð

Ð

ð²

ÿ

Ð

Ð

ð²

ÿ

Ł²

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

ð

ý

Ł

ð

½

þ

þ

½

Ł

ð

ð

ô

ô

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¼

¼

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł²

ð

½

½

Ł

ð

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

¼

Ð

Ł²

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ł

²

²

ô

ô

Ł²

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

²

ð¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

²

Ł

Ð

ð²

½

½

ÿ

½

ÿ

Ð

½

ð

ð

ð²

ð

ð

ð

ð

þ

Ł

Ł

Ł

½

½

Ł

þ

Ł

Ł

½

Ł

þ

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð¦

Ð

Ł

Ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

в

Ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

²

ð

Ð

Ð

²

ð²

Ł

ð

Ł

²

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

$

%

!

!

()

S

A

TI

TII

B

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

al

do

do

mo

mo

mio

- ren

- ren

duol,

-do

al

-do,

al

mio

che

mio

duol,

che

duol,

mo-ren

mo

al

-do

al

- ren

al mio

mio

mio

- do

al

duol,

duol

duol,

mor

mio duol,

al

al

- te

al

mio

mio

non

duol,

duol,

mio

sen

duol,

- to,

27

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 3 page 1 of 2

Example 3. Diatonic reduction of Gesualdo, Ma tu, cagion, mm. 27–34

264

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

adams_03 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

+

+

Š

Š

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

²

Ð

ð

ý

ð

ð

ð²

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ý

²

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ý

Ð

ð

ý

ð

ý

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ý

ý

ð

ð

Ð

Ł

ð

ð

ý

ð

ý

ð

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ð

Ð

Ł

ð²

Ð

Ð

ð

Ð

ÐŁ

²

Ð

ð

Ð

ÐŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ð

Ð

ð

Ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

²

²

²

ð²

ð

ð²

½

½

½

½

ð

ð

ð

²

²

ô

ô

ðý²

ð²

ð

ý

²

¼

ðý²

ð

¼

ð

ð

ð

ý

ý

ý

²

²

²

ð²

ð²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ô

ô

ð²

ð²

þ²

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

²

$

%

!

!

²

²

S

A

TI

TII

B

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

mor - te non sen - to, mor

mor

mor

mor

mor

- te

- te

non

- te

- te

- te

non

sen

non

non

non

sen

sen

sen

sen

- to

- to

- to

- to

- to

31

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 3 page 2 of 2

Example 3 (continued) Diatonic reduction of Gesualdo, Ma tu, cagion, mm. 31–34