Adams, Kyle: A New Theory of Chromaticism from the Late Sixteenth to the Early Eighteenth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

275

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

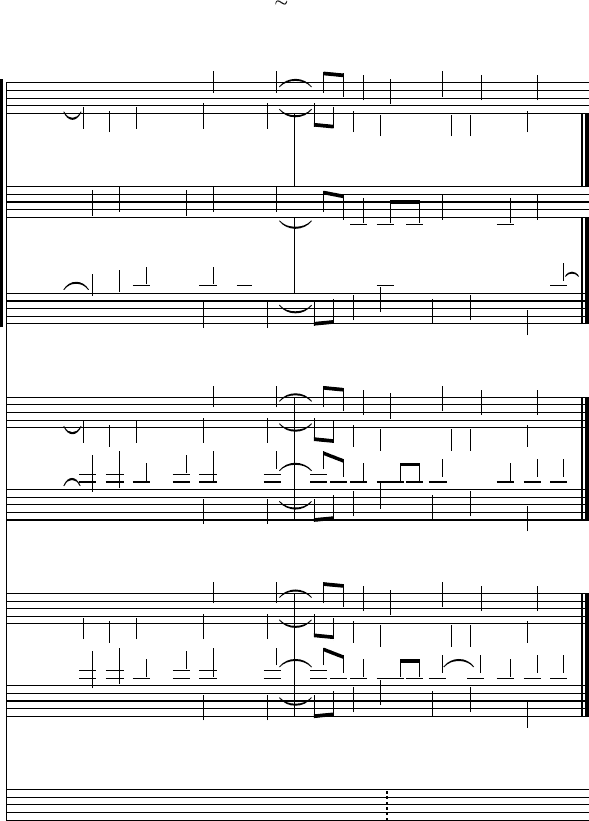

represents the listener’s perception of the music to say that, while the F≥ is an

essential chromatic pitch, it is a rare essential chromatic pitch that does not

signal a change of tonal system. The nonessential nature of the F≥ is clearly

defined by the motion F–F≥–G in the tenor voice and the sequential nature of

the passage. In this sequence, the chords on the second and fourth beats are

clearly subordinate to those on the first and third beats, since the former are

what we would call applied dominants. One might therefore say that while the

F≥ is “essential” in order to create a perfect fifth with the bass, it is nonessential

in the larger sense of being part of a nonessential sonority. Therefore, the

reduction shows the first measure being governed by the natural system.

adams_08 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:00 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ł

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ł

¦

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ł

−

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł−

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

¼

¼

½

¼

¼

½

¼

¼

½

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

ý

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł²

Ł²

Ł¦

ð

ð²

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð²

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

$

%

!

!

() ()

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

di

o gra - di

- ta

- ta

Vi

Vi

- ta

- ta

del

del

- la

- la mia

mia

vi

vi - ta

- ta

3

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 8 page 2 of 2

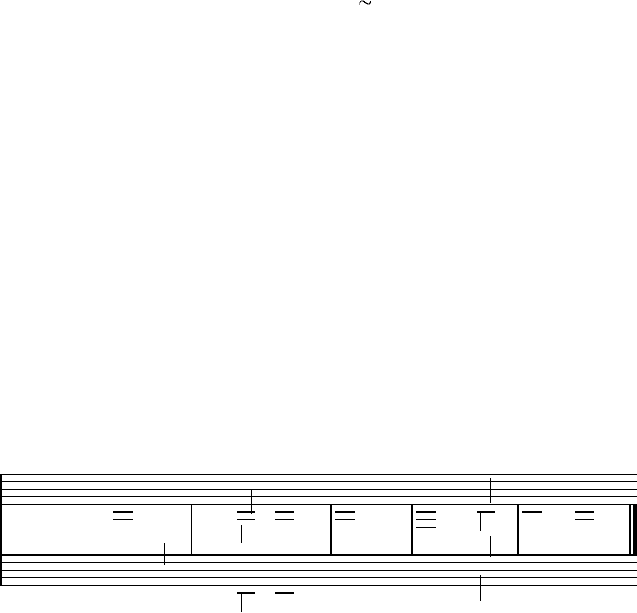

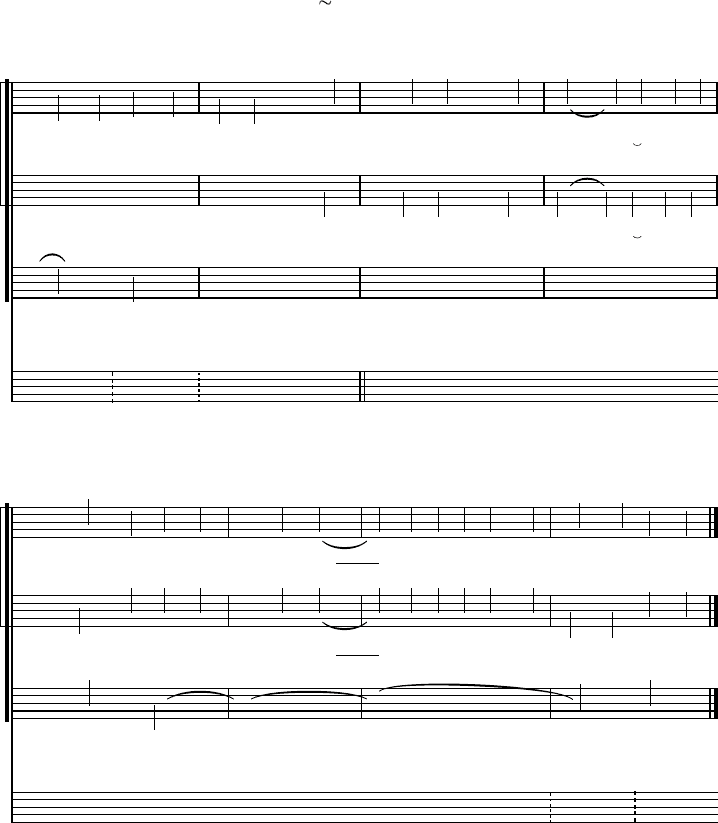

Example 8 (continued) Reduction of Nenna, Ecco, ò dolce, ò gradita (1607), mm. 3–4

276

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

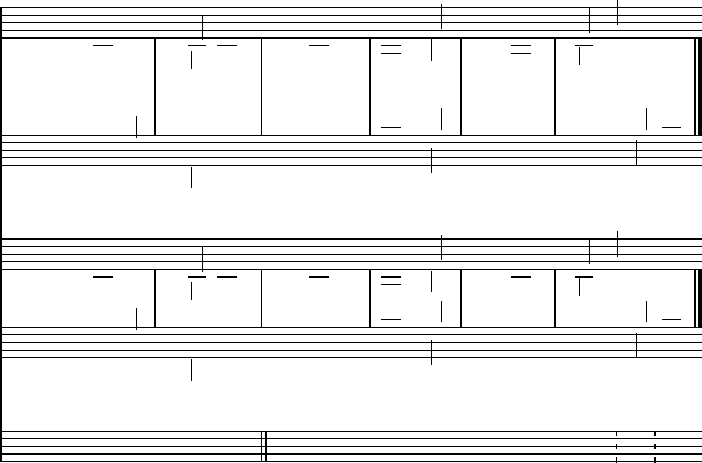

As I have shown in the reduction, however, the music does change to

the one-flat system beginning with the G-minor sonority in m. 45. This sonor-

ity serves as the goal of directed motion rather than a sonority that provides

such motion. An analysis consistent with what has come before would read

the tones of this sonority as diatonic. Just as in the previous tenor progres-

sion F–F≥–G, the F≥ was a chromatic alteration, so, in this tenor progression

B≤–BΩ–C, the BΩ is read as a chromatic alteration, albeit another essential chro-

matic alteration that does not signal a change of system. The corresponding

change to the one-flat system also accounts for the B≤-major sonority in the

following bar. The final chromatic tone in the passage, C≥, remains in stage 1

of the reduction because it is syntactically required at the cadence.

Juxtaposed diatonicism

Juxtaposed diatonicism is perhaps the most difficult type of chromaticism to

identify, since its use is often independent of the chromatic semitone, and

adams_09 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 2 pages

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

ý

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

−

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

Ł

�

!

!

!

¦

−

()

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

44

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 9 page 1 of 2

adams_09 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

−

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Łý

Ł

Łý

Ł

Łý

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

−

−

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

−

−

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

−

−

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

¦

Ł

�

Ł

�

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

�

²

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

�

²

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

�

¹

Ł

¹

Ł

¹

Ł−

Ł

Ł²

Ł

¼

Ł

¼

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

!

!

!

()

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

46

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 9 page 2 of 2

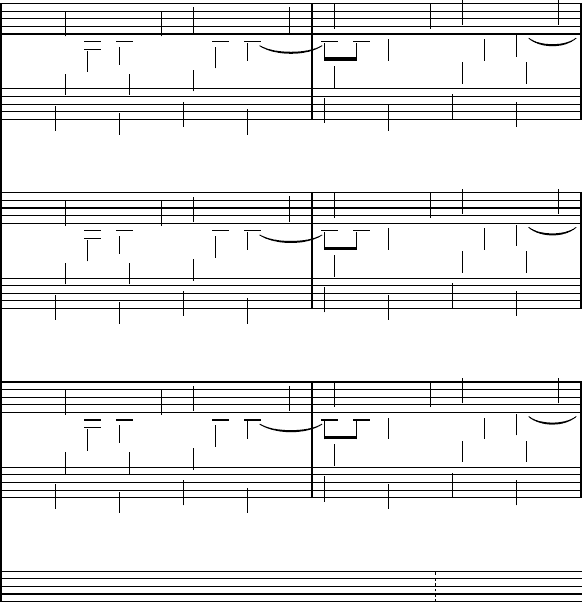

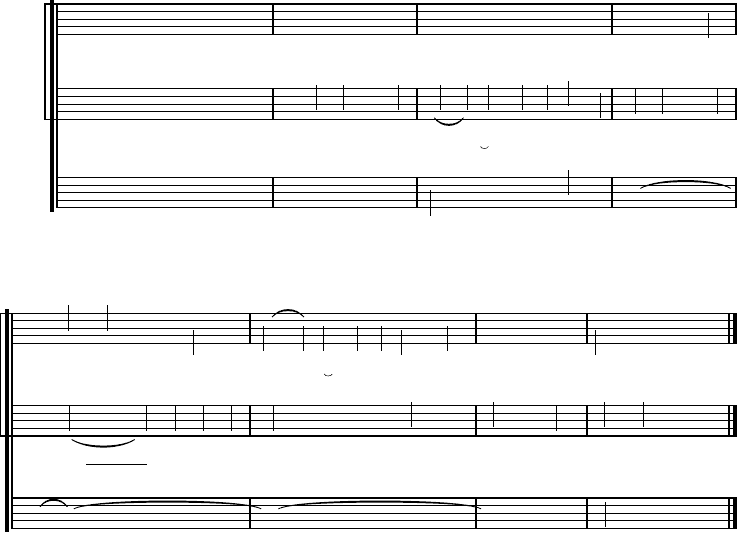

Example 9. Reduction of Scheidemann, Praembulum (early seventeenth century), mm. 44–45

277

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

since its identification often relies on subjective judgment. Unlike examples of

essential and nonessential chromaticism, it has little or no basis in sixteenth-

or seventeenth-century music theory.

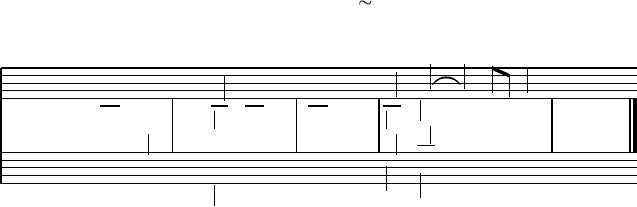

Example 10 presents a diatonic reduction of the first nine bars of the

celebrated Prologue to Lasso’s Prophetiae Sibyllarum.

26

The piece begins in the

natural system, which Lasso juxtaposes against the four-sharp system in m. 3.

This system remains in effect until the second chord of m. 6, whose DΩ signals

a change to the three-sharp system. The following series of bass motions down

by fifth carries a change of system with each chord change until the arrival of

the one-flat system, which is juxtaposed against the one-sharp system on the

downbeat of m. 8. Stage 2 has been omitted from the reduction because the

passage contains no type A alterations to remove. Even though the two final

adams_09 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

−

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Łý

Ł

Łý

Ł

Łý

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

−

−

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

−

−

ð

Ł

Ł

ý

−

−

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

¦

Ł

�

Ł

�

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

�

²

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

�

²

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

�

¹

Ł

¹

Ł

¹

Ł−

Ł

Ł²

Ł

¼

Ł

¼

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

!

!

!

()

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

46

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 9 page 2 of 2

Example 9 (continued) Reduction of Scheidemann, Praembulum (early seventeenth century),

mm. 46–47

26 As I noted above, the presentist/historicist debate

regarding early chromaticism has played out almost entirely

in reference to this piece; see Mitchell 1970, Berger 1976,

Lake 1991, and Bent 2002.

278

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

adams_10 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

‡

‡

‡

‡

Ð

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ý

Ð

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ý

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ð

ð

þ

þ

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

²

²

²

þ

þ

þ

þ

²

²

þ

þ

þ

þ

²

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

²

²

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

²

²

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

²

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

²

²

²

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

²

²

²

Ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

−

−

Ð

Ð

Ð

−

−

ð

ð

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

−

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ł

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ł

Ł²

Ł²

Ł

Ł

ð²

ð²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

!

!

!

!

¦

¦

¦

¦

¦

−

Score

Stage 1

Tonal

Systems

Score

Stage 1

Tonal

Systems

Car

(Car

- mi - na

- mi - na)

Chro - ma - ti - co quae

au

au - dis

- dis

mo

mo

- du

- du

la

- la

- ta

- ta

te

te

- no

- no - re

- re

6

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 148-9 Adams Example 10

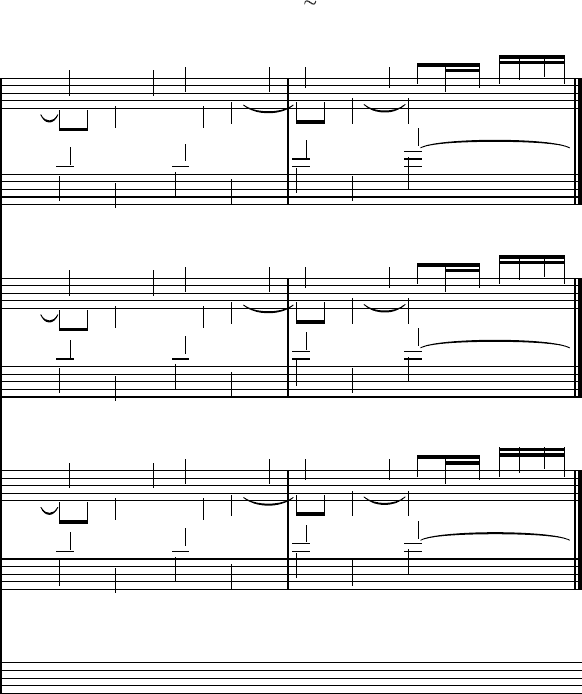

Example 10. Reduction of Lasso, Prologue from Prophetiae Sibyllarum (1560), mm. 1–9

279

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

F≥’s in the cantus serve to create directed motion to the following G, they are

diatonic tones rather than chromatic alterations, since the one-sharp system

governs this progression. In fact, the only nonessential alteration in the entire

passage is the type B alteration of EΩ to E≤ in the bass of m. 8.

Example 10 also demonstrates the application of the principles of pre-

ferred diatonicism and greater simplicity. The B-major sonority in m. 3 ush-

ers in a new, four-sharp system according to the principle of preferred dia-

tonicism. Without this principle, one is forced to somehow integrate the next

four sonorities into the natural system as chromatic alterations of underlying

diatonic sonorities. however, while Lasso’s triads on B, C≥, E, and F≥ are chro-

matic in relation to the G harmony that came immediately before, they are

certainly not chromatic in relation to one another. In fact, if the entire passage

were transposed as in Example 11, the opening would appear chromatic while

mm. 3–5 would appear diatonic.

adams_11 (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

‡

‡

ÿ

Ð

ÿ

ÿ

ý−

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

−

−

ð−þ−

ð

ð

ð

−

−

Ð

Ð

Ð

−

−

þ

þ

þ

þ

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

!

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 148-9 Adams Example 11

Example 11. Transposition of the first five bars of the Prologue

This suggests that Lasso’s chromaticism does not have a single diatonic

foundation, but rather stems from the side-by-side placement of two incom-

patible diatonic passages. The advantage of reading juxtaposed diatonicism in

this and other such examples is that it highlights the fact that many sonorities

belong to the same diatonic system, without attempting to create a functional

hierarchy between the sonorities or the systems.

One might argue that the B-major sonority in m. 3 is an alteration of an

underlying B-minor triad, and that the D≥ serves to create directed motion

to the next sonority in the manner of an evaded cadence. This would lead to

the diatonic reduction presented in Example 12. (I present only the first six

measures, since the remainder of the reduction would be the same.)

here, the relevant juxtaposition would occur in m. 3 between the

one-sharp and three-sharp systems. But this reading ignores the very moment

that gives the passage its chromatic sound, namely, the change from the G-major

to the B-major harmony. (recall that the principle of preferred diatonicism

gives preference to a tonal system in which the first sonority of a group is dia-

tonic.) Example 10 is therefore a much simpler interpretation, and one that

corresponds more closely to the listener’s experience of the music.

280

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

One final point about Example 10: The presence of only four pitch-

classes in mm. 1–2 means that those measures could be interpreted in either

the natural or the one-sharp system. I have interpreted them in the natural

system in accordance with the absence of F≥ in the gamut. While this situation

does not arise often enough to warrant its inclusion as a principle, the reduc-

tions will show a preference for interpreting tones belonging to the gamut of

musica recta as diatonic.

Distinguishing juxtaposed diatonicism from nonessential chromaticism. One

defining characteristic of juxtaposed diatonicism is the placement of two

incompatible tonal systems alongside one another, not just two incompatible

sonorities. If Lasso’s Prologue continued as in Example 13, the soprano D≥

would simply be a type B nonessential alteration and could be removed to

reveal an underlying one-sharp system.

Instead, juxtaposed diatonicism is created by the continuation of a sys-

tem in which the D≥ and its corresponding B-major triad become diatonic.

The reading given in Example 10 recognizes that, while the harmonies in

mm. 4–6 may be chromatic in relation to the harmonies in mm. 1–2, they are

diatonic in relation to each other; it is the system to which they belong that

is chromatic.

Notice that mm. 6–7 of the Prologue contain a chromatic circle-of-fifths

progression, one of the most common ways that composers—especially Lasso—

introduced chromaticism in this period. The different ways of analyzing such

progressions bear heavily on the concept of juxtaposed diatonicism because

adams_12 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

‡

‡

‡

‡

Ð

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ý

Ð

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ý

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ð

ð

þ

þ

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

²

²

þ

þ

þ

þ

²

²

þ

þ

þ

þ

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

²

²

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

²

²

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

²

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

²

²

²

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

²

²

Ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

!

!

¦

¦

¦

Score

Stage 1

Tonal

Systems

Car

(Car

- mi - na

- mi - na)

Chro - ma - ti - co quae au

au-dis

- dis

mo

mo

-

-

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 12

Example 12. Alternate reduction, first six bars of the Prologue

281

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

most examples of it are either preceded or followed by such progressions.

Often, a juxtaposition is followed by a descending circle-of-fifths progression

that returns to the original system. Klaus hübler (1976), in his analysis of the

Prophetiae Sibyllarum, explained Lasso’s chromaticism in just this way, as con-

sisting of a Sprung, or leap to a distant harmony, followed by motion around

the circle of fifths. Alternatively, a descending circle-of-fifths progression that

has “gone too far” and left the original system is followed by a juxtaposition

to bring the original system back. The following illustrates how this theory

accounts for such progressions.

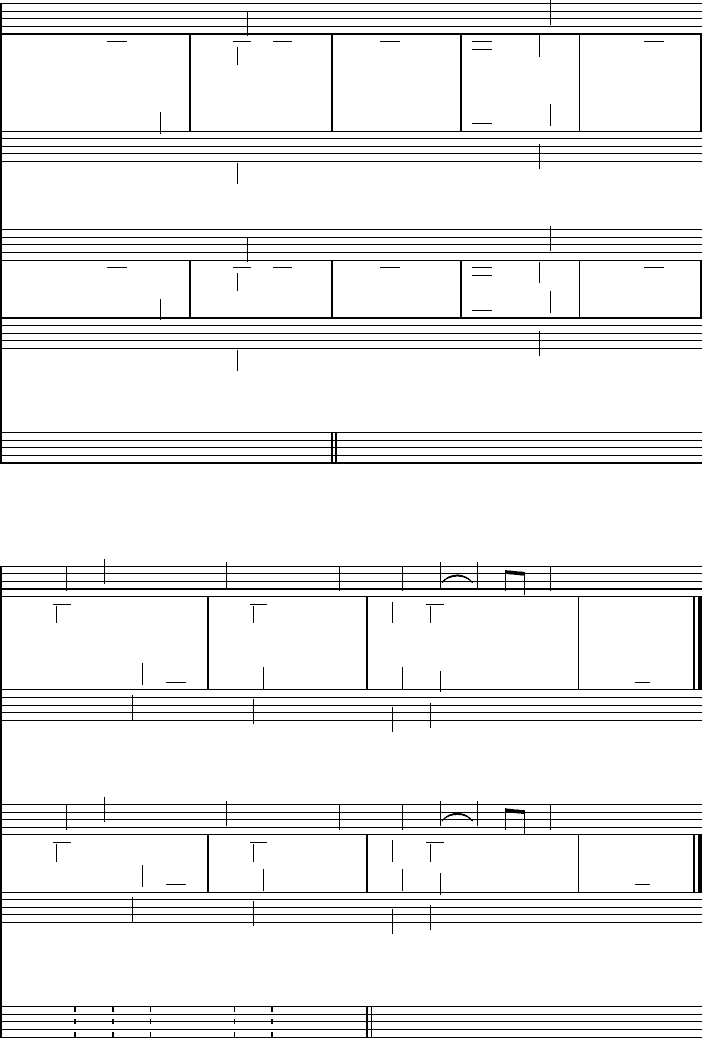

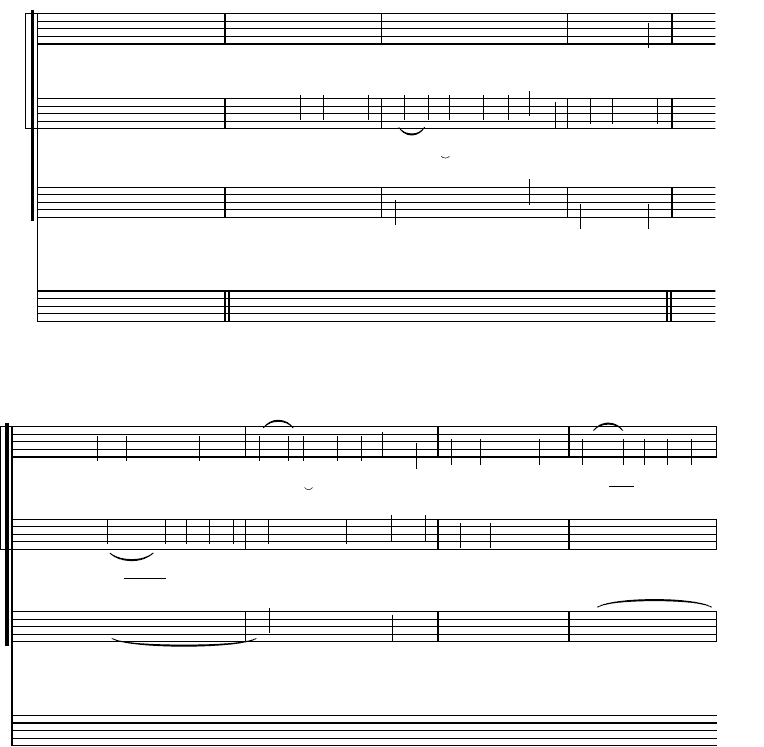

Consider mm. 113–28 from Claudio Monteverdi’s well-known canzo-

netta Zefiro, torna, presented as Example 14. This passage could be read as a

series of nonessential chromatic alterations within the one-sharp system. In

such a reading, the chromatically altered tones in mm. 114–16 and parallel

passages could be seen as type B alterations creating directed motion to the

following sonorities. Nevertheless, the reduction shows this succession as a

true instance of juxtaposed diatonicism. The difference lies in context. The

fourth measure of the excerpt does indeed return to a sonority belonging

to the one-sharp system that has governed the piece so far, but, after m. 113,

there is never a sonority that belongs exclusively to the one-sharp system. If

the passage proceeded as in Example 15, the E-major and A-major sonorities

would be perceived in retrospect as chromatic alterations.

Not only does Monteverdi not return to the one-sharp system, but he

introduces a second juxtaposition to the four-sharp system. This time, the

succeeding circle-of-fifths progression returns to the one-sharp system, but

Monteverdi spends enough time in the new system that m. 117 is perceived in

retrospect as motion to a new tonal system rather than as a series of chromatic

alterations.

27

This theory must allow for a certain amount of subjectivity in determin-

ing whether chromatic juxtapositions will be perceived as nonessential chro-

maticism or a move to an entirely new system. Factors other than harmony can

adams_13 (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

‡

‡

Ð

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ý

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ðþ

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

þ

þ

þ

þ

²

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ł

Ł²

Ł

ð

þ

þ

þ

þ

!

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 13

Example 13. Prologue with alternate continuation

27 Example 14 would seem an ideal place to apply Hübler’s

concept of a Sprung to a distant harmony followed by motion

around the circle of fifths; one might wonder whether it is

appropriate to describe Monteverdi’s chromaticism in terms

of Sprünge. While the idea of a Sprung would accurately

describe the juxtapositions in mm. 113–14, 116–17, and

122–23 of this example, Hübler’s concept does not provide

a complete picture of a passage such as this one. In par-

ticular, it does not address the issue of the relationship of

the Sprünge to the underlying tonal systems. Sprünge, like

single chromatic tones, do not always exist for the same

reason or serve the same purpose.

282

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

influence one’s hearing of a passage; in Example 14, the change of meter and

the change from a dancelike character to a recitative reinforce the sense of

juxtaposed diatonicism.

28

Nevertheless, from the preceding examples we can

induce some criteria that serve to separate examples of juxtaposed diaton-

icism from other types of chromaticism. First, the listener is much less likely

adams_14 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:01 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 2 pages

+

+

+

+

Š

Š

Ý

Š

/

-

/

-

/

-

þ

Ð

þ

ý

ÿ

ÿ

Ð

‡

‡

‡

²

²

²

ÿ

Ł²

Ð

Ł¼Ł

ÿ

Ł²

ð

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Łý

ð²

Ł

�

½

Ł²

ð

Ł

¼

¼

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

²

²

²

$

%

Š

Š

Ý

Š

²

²

²

²

Ł²

ð²

Ð

Ł

¼

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł²

Łý²

ð

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

�

Łý

Ł

ý

²

ð²

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł²

Ł

Ð

Ł

Ł

¼

½

Łð²

ÿ

Ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

$

%

²

²

²

²

Tenor 1

Tenor 2

(Basso

Continuo)

Tonal

Systems

T1

T2

B.C.

Tonal

Systems

to

to Sol i - o per sel - ve ab-ban-do-na - te so - le

Sol

l’ar -

i

dor

-o

di

per

due be

sel

- glioc

- ve

ab-ban

- chiel

-do-na

mio

- te

tor

so

- men

- le

- to

l’ar - dor di due be -

113

117

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 14 page 1 of 2

Example 14. Reduction of Monteverdi, Zefiro, torna (1632), mm. 113–20

28 Gioseffo Zarlino himself emphasized that chromaticism

was as much a stylistic phenomenon as a structural one:

“There cannot be a difference in genus between compo-

sitions that do not sound different in melodic idiom. . . .

Conversely, a difference of genus may be assumed when

a notable divergence in melodic style is heard, with rhythm

and words suitably accommodated to it” ([1558] 1968, 277).

Dahlhaus (1967) makes a similar point, noting that chro-

maticism arises not only from the juxtaposition of unrelated

harmonies, but also from the rhythmic isolation, metrical

relationship, and position (i.e., inversion) of those harmo-

nies (78–79).

283

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

to perceive a change in system if, following a potential juxtaposition, the com-

poser introduces a sonority that was diatonic in the original system but would

not be in the new one. Such a sonority will probably not sound chromatic in

a new system but will serve as a reminder of the original tonal system, against

which previous chromatic events will stand out as nonessential alterations.

Second, the likelihood that the listener will perceive a change to a different

tonal system increases with the number and duration of sonorities that belong

to that system and not the previous one.

Juxtaposed diatonicism arising from nonessential chromaticism. Example 16,

mm. 20–26 from henry Purcell’s Gloria Patri, illustrates how a chromatic tone

adams_14 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:01 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

+

+

+

+

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Łý²

ÿ

ð

Ł

�

Ł

ý

ð²

Ł

�

¦

Ł

½

Ð

Ł

¼

¼

Ł

Ł

²

²

²

Ł²

Ł

Ð

Ł

Ł

¼

¼

Ł

Ł

ð²

ð

Ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

$

%

Š

Š

Ý

Š

²

²

²

Łý

Łý²

ð²

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł²

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

¼

¼

Ð

Ł²

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ð

Ł

�

²

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Łý

Łý

Ł

�

Ł

�

¦

Ł

ý

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

$

%

¦

¦

²

²

T1

T2

B.C.

Tonal

Systems

T1

T2

B.C.

Tonal

Systems

glioc - chiel mio tor - men - to sol

sol

i

i

-o

-o

per

per

sel

sel

- ve ab

- ve

ab

-ban

-ban

-do

-do

-

-

na

na

- te

- te

so

sol

- le

- le

l’ar

la’r

- dor

- dor

de

de

due

due

be

be

-gl’oc

-gl’oc

- chiel

- chiel

mio

mio

tor

tor

-men

-men

- to

- to

121

125

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 14 page 2 of 2

Example 14 (continued) Reduction of Monteverdi, Zefiro, torna (1632), mm. 121–28

284

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

that was originally nonessential can introduce a juxtaposition to a new tonal

system. The passage begins in the three-flat system that governs most of the

piece, as indicated by Purcell’s signature. Within this system, the soprano BΩ

in m. 22 is a type A alteration that, along with the alto F, creates expecta-

tion of directed motion to a C-minor sonority. (It is a type A rather than a

type B alteration since coming to rest on a minor seventh chord would have

been syntactically incorrect in this repertoire.) Nothing from m. 22 resolves

as expected: The F, a chordal seventh, leaps to D and then G before resolv-

ing, and when it does resolve, it moves to EΩ instead of E≤.

29

Moreover, the

BΩ remains in the chord instead of resolving to C.

30

The harmonies that fol-

low are diatonic in relation to the E-minor sonority, creating the juxtaposi-

tion of the three-flat and natural systems shown in the reduction. The BΩ has

therefore changed from a nonessential chromatic pitch into a diatonic pitch.

adams_15 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:01 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

+

+

+

+

Š

Š

Ý

/

-

/

-

/

-

þ

Ð

þ

ý

ÿ

ÿ

Ð

‡

‡

‡

ÿ

Ł²

Ð

Ł¼Ł

ÿ

Ł²

ð

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Łý

ð²

Ł

�

½

Ł²

Ð

Ł

¼

¼

Ł

Ł

$

%

Š

Š

Ý

Ł

ð²

Ð

Ł

¼

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

ð²

Ð

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

�

�

Ł

ý

ð

Ł

�

Ð

ð

ý

Ð

Ł²

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

½

½

½

$

%

²

²

Tenor 1

Tenor 2

(Basso

Continuo)

T1

T2

B.C.

to Sol i - o per sel - ve ab-ban-do-na - te so - le

Sol

l’ar -

i

dor

-o

di

per

due be

sel

- glioc

- ve

ab-ban-do-na

- chiel

- te so

mio tor

- le

- men - to

5

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 15

Example 15. Alternate version of Zefiro, torna

29 I consider the motion to E in m. 23 a resolution of the F

from m. 22, albeit a highly decorated one.

30 None of the voice parts in m. 23 contains a literal car-

ryover of BΩ from one sonority to the next. However, I

have included the editorial realization of the figured bass

by Anthony Lewis and Nigel Fortune, which shows that the

retention of BΩ is part of the underlying voice leading. The

claim that BΩ “remains” in the chord is not invalidated by

the fact that this voice leading is not literally expressed by

any one part.