Adams, Kyle: A New Theory of Chromaticism from the Late Sixteenth to the Early Eighteenth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

265

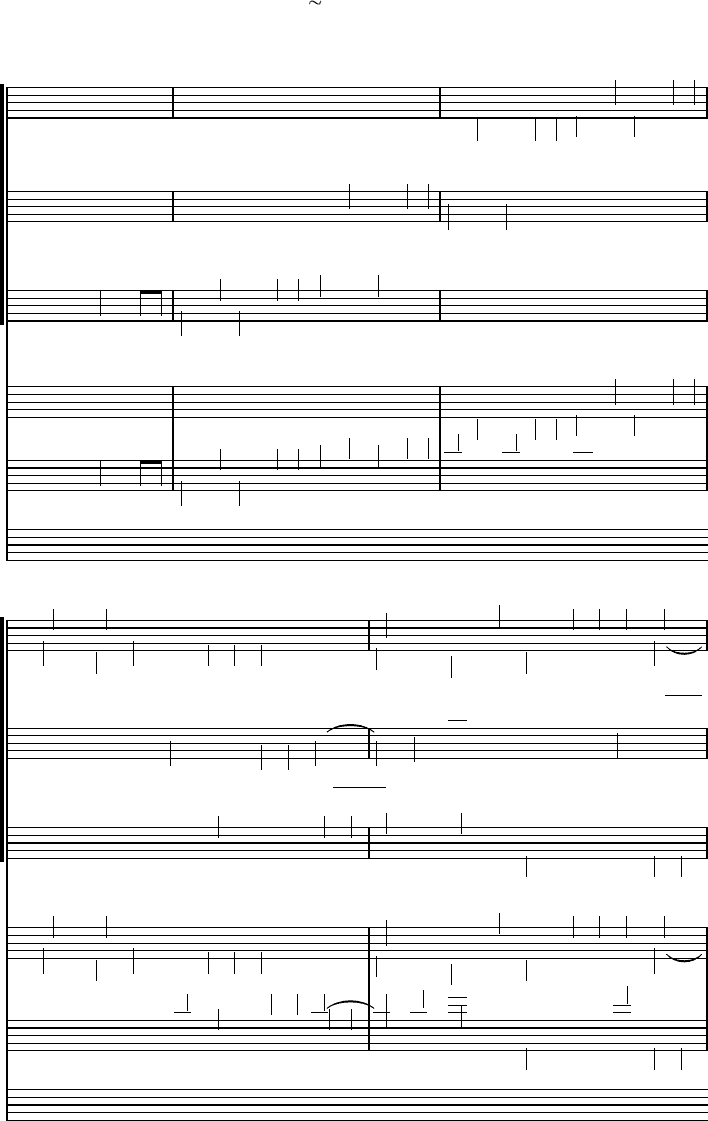

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

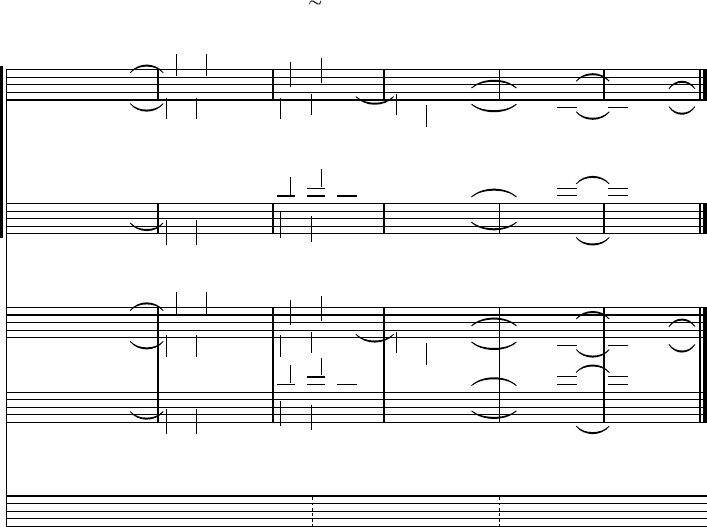

reintroduced in the soprano to form a perfect fifth with the upcoming bass

F≥.) The two-sharp system governs the passage through the middle of m. 31,

within which one can see the removal of two type B alterations (CΩ and G≥ in

mm. 29–30) in stage 1, and two type A alterations (the tenor 2 D≥ in m. 30 and

the bass G≥ in m. 31) in stage 2.

The passage returns to the one-sharp system in the middle of m. 31,

again via indirect chromaticism, as indicated by the dotted barline and can-

cellation of C≥ by CΩ on the lowest staff. (The F≥ and C≥ at the beginning of

the lowest staff in m. 31 are courtesy accidentals and do not represent any

change.) Within this system, the leading tone G≥ in tenor 2 has been removed

in stage 2 of the reduction, since it is a type A alteration. At the end of m. 32

is a double barline, followed by a signature of three sharps. This signifies jux-

taposed diatonicism, which is the juxtaposition of two tonal systems via direct

chromaticism.

21

here, the music abruptly moves into the three-sharp system

via the introduction of C≥ and G≥ on the downbeat of m. 33. Typically, as in this

example, the two tonal systems participating in juxtaposed diatonicism will

differ by more than one accidental. The only chromatic phenomenon from

Figure 1 not occurring in this passage is suspended diatonicism, which would

be indicated via a double barline followed by no signature.

Just as in the tonal progressions given in Example 1, this method allows

for the same phenomenon to be analyzed in different ways, depending on

context or function. Thus, in m. 32, the leading tone G≥ in tenor 2 has been

removed because it is chromatic within the governing one-sharp system. how-

ever, in the final measure, the alto leading tone G≥ remains in the reduction

because it is diatonic within the governing three-sharp system.

There are two guiding principles of diatonic reduction. The principle

of preferred diatonicism states that the governing tonal system of a passage will

always be the one in which the greatest possible number of sonorities are dia-

tonic. Preference will be given to a tonal system in which the first sonority of

a passage is diatonic; however, as we shall see, many passages begin with chro-

matic sonorities. The principle of greater simplicity states that the stages of the

reduction must become successively more diatonic. The reduction may not

create chromaticism that was not present in the original passage. I illustrate

both of these principles in the examples that follow.

Diatonic reductions can be used in conjunction with the continuum of

Figure 1 to describe the types of chromaticism at play in a given passage. By

examining the single staff at the bottom of a reduction, a reader can deter-

mine whether a given passage is diatonic or uses indirect or direct chromati-

cism. If a given point on the lowest staff has no barline (which will be the

majority of the staff) and is preceded by a key signature, the passage above

21 This is an important distinction, to which I return further

below: Juxtaposed diatonicism requires the placement

alongside one another of two incompatible tonal systems,

not just two incompatible sonorities.

adams_03 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

+

+

Š

Š

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

²

Ð

ð

ý

ð

ð

ð²

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ý

²

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ý

Ð

ð

ý

ð

ý

ð

ð

Ð

ð

ý

ý

ð

ð

Ð

Ł

ð

ð

ý

ð

ý

ð

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ð

Ð

Ł

ð²

Ð

Ð

ð

Ð

ÐŁ

²

Ð

ð

Ð

ÐŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ð

Ð

ð

Ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

²

²

²

ð²

ð

ð²

½

½

½

½

ð

ð

ð

²

²

ô

ô

ðý²

ð²

ð

ý

²

¼

ðý²

ð

¼

ð

ð

ð

ý

ý

ý

²

²

²

ð²

ð²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ô

ô

ð²

ð²

þ²

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

²

$

%

!

!

²

²

S

A

TI

TII

B

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

mor - te non sen - to, mor

mor

mor

mor

mor

- te

- te

non

- te

- te

- te

non

sen

non

non

non

sen

sen

sen

sen

- to

- to

- to

- to

- to

31

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 3 page 2 of 2

266

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

it is diatonic in the tonal system represented by the signature, and any chro-

matic tones appearing in the score at that point are nonessential alterations.

They will have been removed in either stage 1 or stage 2 of the reduction.

rightward motions on the continuum are represented by barlines in the

reduction. Dotted barlines signal the use of indirect chromaticism, double

barlines followed by a key signature signify juxtaposed diatonicism, and dou-

ble barlines followed by no key signature signify suspended diatonicism. In all

cases, the lowest system of music in the diatonic reduction will contain only

tones that are diatonic in the tonal system shown on the bottom staff.

II. Analyses

Essential and nonessential chromaticism

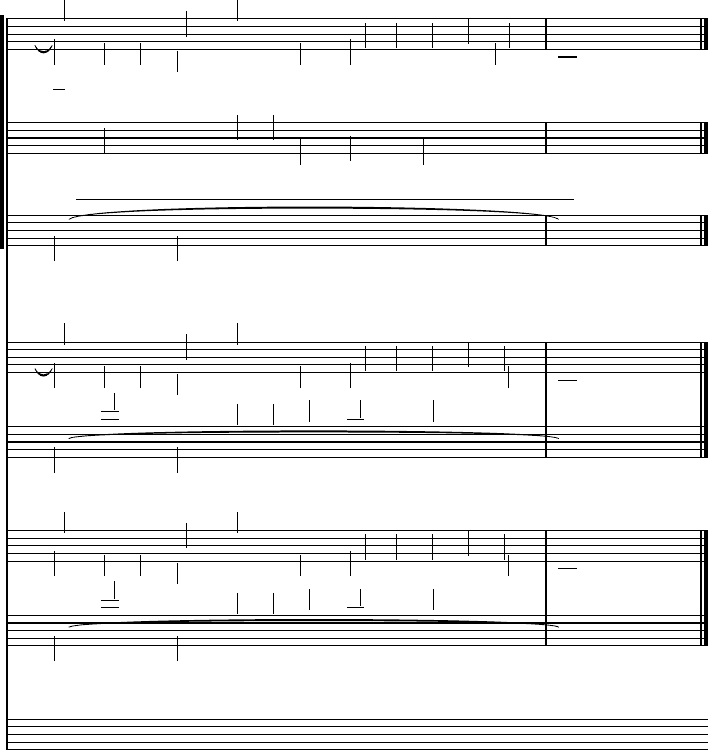

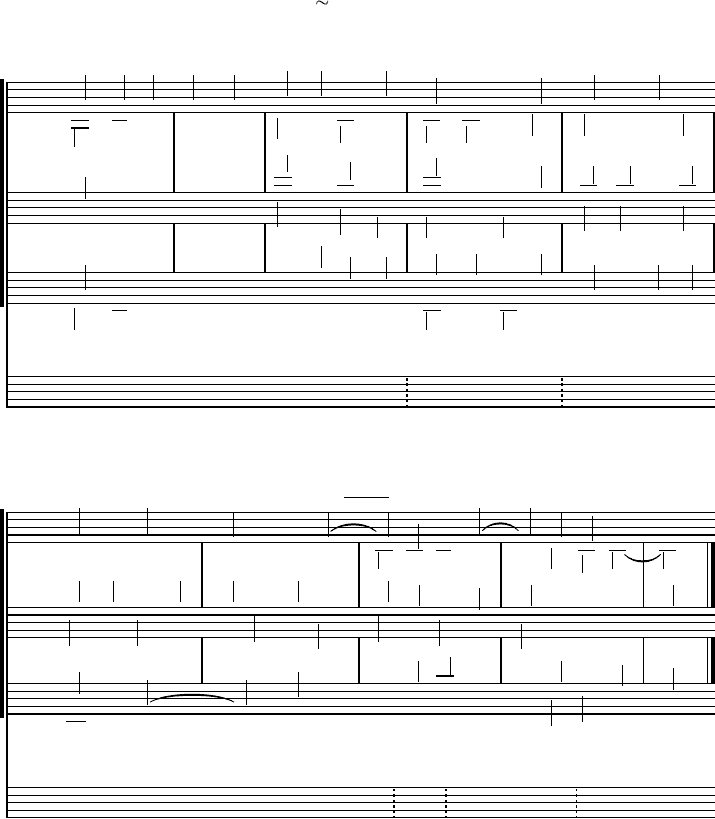

Nonessential chromaticism. Example 4 presents a diatonic reduction of

mm. 23–29 from Luzzasco Luzzaschi’s madrigal Lungi da te. All but two of the

semitones in the passage are type B nonessential alterations, since they do not

serve to correct any potential errors in part writing. These alterations have

therefore been removed to create the stage 1 reduction in the second system.

Notice that two penultimate G≥’s in the cantus remain, since they are type A

alterations: Both serve as leading tones to the following A, and the A between

them is only a decoration. The third system removes these alterations as well.

The single staff underneath the example has only a BΩ, indicating that the

entire passage is in the natural system.

One could argue that the distinction between type A and B alterations

is false. Almost every nonessential alteration involves raising a pitch, which

automatically creates directed motion to the following sonority, or at least

the expectation of it. In Example 4, all of the chromatic alterations in the

original create directed motion to the following sonority, and it may seem

arbitrary to single out the final alteration as more significant. however, rais-

ing the penultimate tone at the final cadence is a syntactical requirement, and

Luzzaschi’s notation of the alteration was more a reflection of contemporary

performance practice than an expressive chromatic gesture. By contrast, the

other chromatic alterations in the passage can be removed without creating

any violations of musical syntax. They do not belong to the fundamental voice

leading because, motivic considerations aside, the listener has no reason to

expect them. rather, the continual raising of pitches by semitone and the suc-

cessively higher statements of the chromatic tetrachord are probably intended

to portray the rising of the soul to heaven during the blessed death described

in the text.

The diatonic version of a tone does not always have to appear before

its corresponding chromatic version; frequently, a nonessential alteration will

appear before the tone that is altered. Example 5 presents a reduction of

mm. 25–30 from another of Luzzaschi’s madrigals, Se parti i’ moro.

267

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

adams_04 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 2 pages

+

+

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

ÿ

ÿ

¼

¼

ÿ

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ô

ÿ

ð

¼

ð

¼

ô

ð

ð

ð²

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

¼

Ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

ð²

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ÿ

¼

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ÿ

¼

ð

ð

ð²

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

¼

Ð

ÿ

Ð

Ð

Ð

ÿ

ð

¼

ð

ð

ð²

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

$

%

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

ð

ð

Ð

ô

ÿ

ô

ÿ

Ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

²

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ð

ð

¼

¼

ð

Ð

Ł

�

ð

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

Ł

�

Ł

ð

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

ð

Ł

ÿ

ð

ÿ

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

¼

Ð

ð²

Ð

ð

ð

¼

ð

ð

ð

Ð

ðý

Ð

ð

ð

ý

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

¼

ð

ð

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

$

%

!

!

¦

¦

Score

Stage 1

Tonal

Systems

Score

Stage 1

Tonal

Systems

e mo-ri - ro

e

be

mo-ri

-a

- ro

e

be

mo-ri - ro

- ta

-a

e

be

mo-ri - ro

-a

- ta,

e

be

mo-ri

-

-

-

a

ro

ta,

- ta,

be

e

-a

e

mo

(e

- ri - ro

mo - ri - ro

mo - ri

be

- ta,

- ro

be

-a

-a

be

(e

- ta

(e

-a

mo - ri - ro

- ta,

e

be

mo - ri

-

-

-

23

26

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 14908 Adams Example 4 page 1 of 2

Example 4. Diatonic reduction of Luzzaschi, Lungi da te (1595), mm. 23–27

268

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

In a situation that is almost the exact reverse of Example 4, we find a

series of descending statements of the chromatic tetrachord.

22

As indicated

on the lowest staff, this passage is governed by the natural system, which

means that in each statement of the chromatic tetrachord, the chromatic tone

adams_04 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

+

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

ð

Ł

¼

þ

ð

þ

ð

ð

Ł

þ

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

�

ð

ð

Ł

�

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

Ł

ð²

ð

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

�

Ł

ð

�

Ł

ð

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł²

Ł

Ð

Ð

Ł

Ł²

Ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

�

Ł

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

ð

Ł

�

ð

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

þ

þ²

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ²

þ

þ

þ

þ

þ

$

%

!

!

¦

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

a

ro

ta)

mo

(e

- ri - ro

- ta,)

be

e

mo - ri

be

mo

- ro)

-a

-a

- ri

be

- ro

-a

be - a

- ta

- ta

- ta

- ta)

28

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 14908 Adams Example 4 page 2 of 2

Example 4 (continued) Diatonic reduction of Luzzaschi, Lungi da te (1595), mm. 28–29

22 Since this passage is based on the chromatic tetrachord,

one might argue that the “chromatic” tones are in fact

equivalent to diatonic tones. Vicentino, for example, viewed

the tones of the chromatic tetrachord as substitutes for the

tones of the diatonic tetrachord, so one might therefore say

that these tones are “diatonic” in the chromatic genus. This,

in turn, would imply that the tones I have reduced out as

“chromatic” were not, in fact, outside of the tonal system,

since those would be the only tones available in the tonal

system. There may be works for which this is true, but since

Se parti i’ moro contains passages that are clearly diatonic,

it seems fair to say that the chromatic tones in this passage

are not conceived of as structurally equivalent to diatonic

tones.

269

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

Example 5. Reduction of Luzzaschi, Se parti i’ moro (1595), mm. 25–27

adams_05 (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:00 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 2 pages

+

+

+

Š

Š

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

‡

‡

‡

‡

‡

‡

‡

‡

‡

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ý

ðý

ð

ý

ð

ý

²

ðý

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

ý

²

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ðý²

½

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

½

ðý

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

½

ðý

ð

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ð

ðý²

½

ÿ

ô

ÿ

½

Ð

ð

ý

ô

ô

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

Ð

Ð

ðý²

½

½

ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

$

%

!

!

¦

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

Quei

Quei

Quei

Quei

Quei

che

che

che

che

che

cor

cor

cor

cor

cor

- giun

- giun

- giun

- giun

- giun

- se A

- se A

- se

A

- se

A

- se

A

- mor

- mor

- mor

- mor

- mor

per - che

per

di - vi

- che

per

di

- di,

- vi

- che

per

di

-

-

-

25

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 5 page 1 of 2

precedes the diatonic tone. Stage 1 of the reduction shows that nearly all of

the chromatic alterations are type B; only the G≥ in m. 25, which provides

directed motion to a cadence, and the Picardy thirds in mm. 26 and 30 are

type A alterations.

270

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

adams_05 (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:00 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

+

+

+

Š

Š

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

ô

Ð

Ð

ðý²

½

Ð

½

ð

ô

Ð

ý

ô

ô

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

½

Ð

Ð

ðý²

Ð

Ð

ð

½

ý

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

½

ðý²

½

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

½

½

ð

ý

ô

ô

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

ð²

ð

ðý

¼

ð

ð

ð

¼

ð

ð

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¼

Ð

Ł

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ł

¼

Ł

Ð

Ð

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

$

%

!

!

¦

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

di,

vi

che

per

di

- di,

- vi

- che

per

di

- che

- di,

- vi

per

per

di

- che

- vi

- che

- di,

per

di

- di,

- che

di

- vi

di - vi

- vi

di

di

- vi

- vi

- di?

- di?

- di?

- di?

- di?

28

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 5 page 2 of 2

Example 5 (continued) Reduction of Luzzaschi, Se parti i’ moro (1595), mm. 28–30

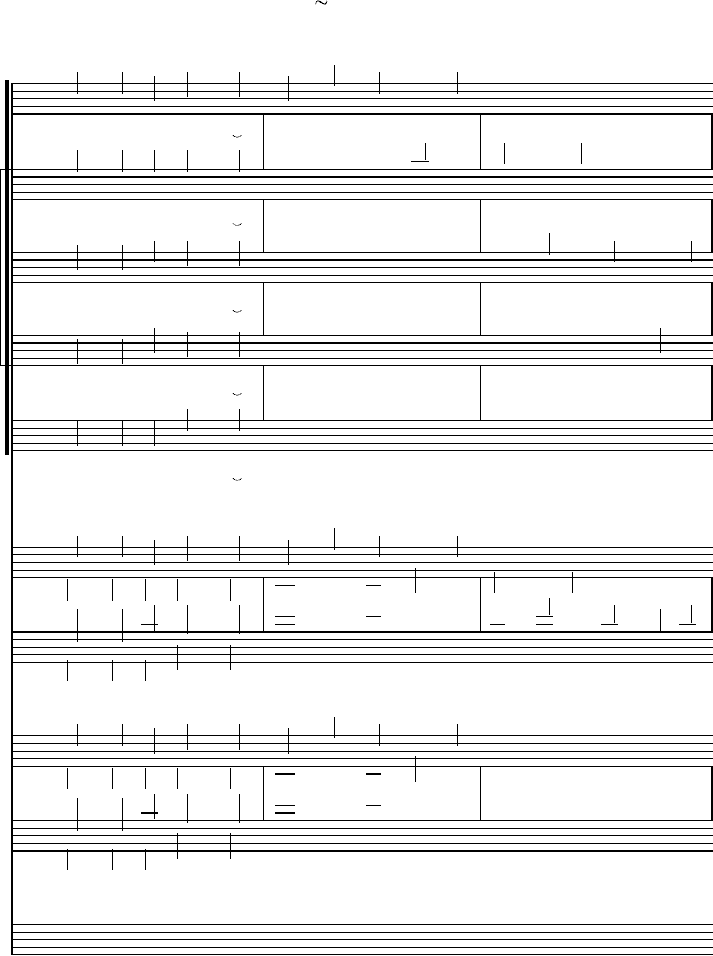

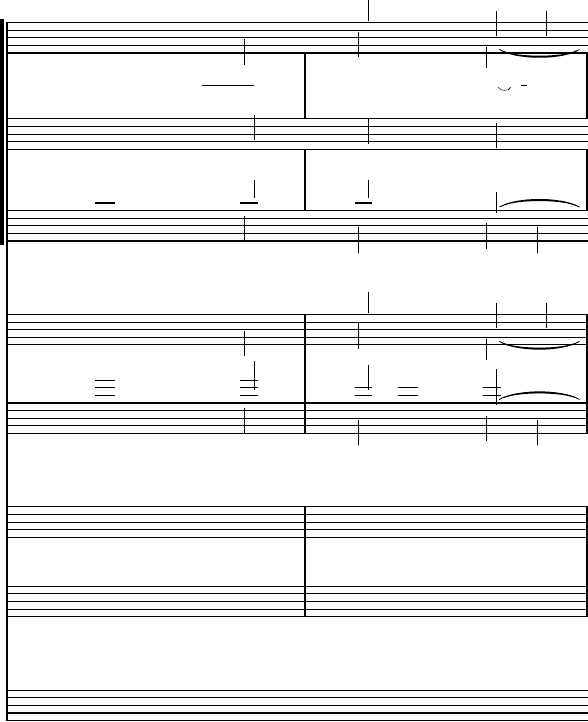

Essential chromaticism. Example 6 presents a reduction of the first six mea-

sures of Lasso’s madrigal Anna, mihi dilecta.

23

This excerpt contains examples

of essential chromaticism. The E≤’s in the bass and tenor of m. 3 are essential

23 Note Lasso’s use of the chromatic tetrachord in the

soprano part of mm. 3–4.

271

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

chromatic pitches, necessary to avoid a diminished fifth against the soprano

B≤. In m. 5, the A≤ in the bass is also an essential chromatic pitch, since it

avoids a melodic diminished fifth from the previous bass E≤.

The first stage of the reduction shows that the F≥ in m. 1 and the BΩ in

mm. 3 and 4 are the only nonessential chromatic pitches. It may seem coun-

terintuitive to call the F≥ of the opening sonority chromatic, but the principle

of preferred diatonicism suggests this reading. After the opening sonority,

subsequent events make it clear that the F≥ was chromatic. More of the tones

in the first four measures belong to the one-flat system than to any system that

would contain the D-major sonority; also, this is a case in which we can claim

with near certainty to know what Lasso intended, since he wrote the one-flat

signature. had he conceived the opening sonority as diatonic, he could have

notated the piece a whole step lower with no signature, making the opening

chord a “diatonic” C-major sonority, and the following one an A≤-major sonor-

ity, which would certainly appear chromatic.

Unlike Examples 2 and 3, however, the passage from Anna cannot be

explained in terms of a single governing tonal system, since the A≤ in m. 5

is incompatible with the AΩ of the opening sonority. This passage therefore

contains indirect chromaticism: Since the A≤-major sonority and the opening

D-major sonority cannot belong to the same tonal system, there must be a

change somewhere. But one cannot point to a single moment as signaling the

change, because any two adjacent sonorities in stage 1 are diatonic relative to

adams_05 (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:00 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

+

+

+

Š

Š

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

ô

Ð

Ð

ðý²

½

Ð

½

ð

ô

Ð

ý

ô

ô

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

½

Ð

Ð

ðý²

Ð

Ð

ð

½

ý

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

½

ðý²

½

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

½

½

ð

ý

ô

ô

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł¦

Ł

ð²

ð

ðý

¼

ð

ð

ð

¼

ð

ð

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¼

Ð

Ł

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ł

¼

Ł

Ð

Ð

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

²

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

$

%

!

!

¦

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

di,

vi

che

per

di

- di,

- vi

- che

per

di

- che

- di,

- vi

per

per

di

- che

- vi

- che

- di,

per

di

- di,

- che

di

- vi

di - vi

- vi

di

di

- vi

- vi

- di?

- di?

- di?

- di?

- di?

28

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 5 page 2 of 2

Example 6. Reduction of Lasso, Anna, mihi dilecta (1579), mm. 1–6

adams_06 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:00 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

−

−

−

−

−

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

ÿ

ÿ

þ

ÿ

þ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

Ð

в

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

Ð

ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð²

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

¦

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

−

−

ð

ð

ð

ð

−

−

Ð

Ð

¦

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

Ð

Ð

¦

Ð

Ð

Ð

ð

ð

ð

Ð

Ð

−

Ð

Ð

−

−

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

−

−

−

−

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

−

Ð

Ð

−

−

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

−

−

−

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ÿ

Ð

Ð

ÿ

Ð

Ð

$

%

!

−

()

()

()

Score

Stage 1

Tonal

Systems

An

(An

- na,

- na)

mi - hi di - le - cta,

(cta)

ve - ni, me -

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 6

272

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

one another. One can only say that the passage begins in the one-flat system

and ends in the three-flat system. The lowest staff in the reduction tracks these

changes in tonal system with dotted barlines followed by the new flats. The dot-

ted barlines indicate that the essential chromatic tones in stage 1 of the reduc-

tion bring about changes of tonal system without any direct chromaticism.

Most examples of essential chromaticism are created by descending-fifth

motion in the bass, as in m. 5 of the previous example. Although it is much

less common, essential chromatic tones can also be created by ascending-fifth

motion. Vicentino used this technique in several of his works. In the excerpt

from Anima mea presented as Example 7, he uses the technique quite beauti-

fully to balance a previous descent by fifth.

As the reduction shows, the passage begins in the one-flat system, which

changes to the three-flat system through a series of descending-fifth motions,

only to cancel the newly added accidentals in the subsequent measures.

Although the chord progression in mm. 97–98 mirrors the progression from

mm. 94–95, the systems do not change accordingly because the sonorities in

mm. 97–98 still belong to the three-flat system, which has not yet been contra-

dicted. Only with the reappearance of AΩ do the tonal systems begin to change

again. Also, because the passage contains only essential chromatic alterations,

both stages 1 and 2 of the reduction have been omitted, leaving only the single

staff to track the changes of tonal system.

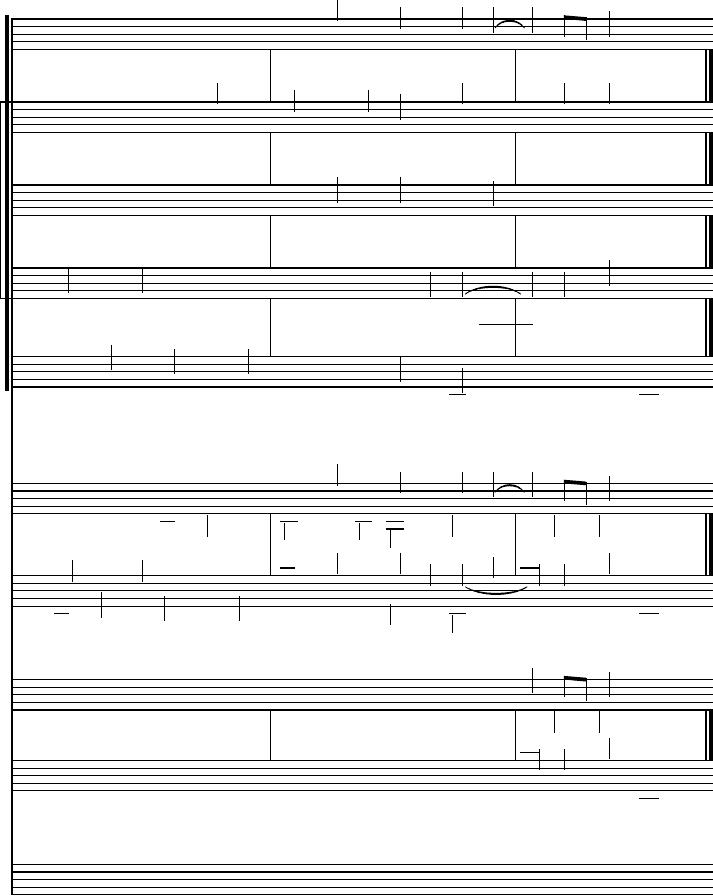

Chromatic tones in the opening sonority. In Example 6, the opening sonority

of a piece contained a chromatic tone. There are many such cases, including

ones where it is quite difficult to distinguish chromatic from diatonic tones.

Example 8 is a reduction of the first four measures of Pomponio Nenna’s

motet Ecco, ò dolce, ò gradita. Even without the B≤ signature, the BΩ of the open-

ing sonority would soon be revealed as a chromatic tone rather than a diatonic

tone. The soprano leap in m. 2 ensures for the listener that B≤ is at least an

essential chromatic tone,

24

if not a diatonic tone, and the persistence of B≤

throughout the measure defines the BΩ at the end of the bar as a chromatic

alteration. Despite the one-flat signature in the music, I consider mm. 1–3 to

be in the two-flat system, since the E≤ in the bass and alto arise as essential chro-

matic tones, against the background of which the alto EΩ in m. 3 becomes a type

A alteration. (The one-flat system that governs most of the piece is not firmly

established until the cadence at the end of m. 4.) Analyzed this way, the striking

E≤ sonority under “dolce” becomes a sweetly relaxing move into the govern-

ing tonal system, rather than a striking chromatic event against the opening

G-major sonority, a reading that I find more consistent with the text.

25

24 At this point in music history, with the innovations of

the secunda prattica, the distinction between essential and

nonessential pitches starts to blur. Nenna does use a verti-

cal diminished fifth between the soprano and alto in m. 4.

However, this diminished fifth is between two upper voices,

both of which are consonant with the bass, and is not nearly

as harsh as a leap of a diminished fifth in the soprano of

m. 2 would be.

25 It is true that “dolce” was often used ironically by com-

posers of this period and therefore was often set using

harsh-sounding sonorities. However, I do not believe that

Nenna intended such a setting here.

273

Kyle Adams A New Theory of Chromaticism

Nonessential chromatic tones with characteristics of essential chromatic tones.

Occasionally, a chromatic tone that is nonessential in origin may also serve to

correct an unallowable dissonance. Example 9 presents a reduction of mm.

44–47 from heinrich Scheidemann’s Praembulum from the Anders von Düben

Tablature.

The Praembulum illustrates the frequent ambiguity between the natural

and one-flat systems in pieces with a D final: B≤ and BΩ will each be diatonic

at various times, depending on whether a particular voice moves upward or

downward, and most such pieces will shift frequently between the two systems.

This piece is in the natural system with a final on D, and BΩ is the primary form

adams_07 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed May 5 12:13 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

Ý

Š

−

‡

‡

‡

ð

ð

ÿ

ð

ð

ð

½

Ł

½

½

½

Ł

ÿ

ð

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ð

ð

Ł−

ð

ð

Ð

¼

−

ð−

Ł−

ð−

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł−

Ł−

Ł

−

ð

Ł−

ð

ð

ý

−

−

ð

Ł

−

ð−

ð

¼

ð−

ð−

Ł

Ł−

Ł−

Ł

−

ð

ð

ý

−

−

Ł

Ł−

Ð

ð

−

ð

ð

−

ð−

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

$

%

Š

Ý

Ý

Š

−

Ð

ð

−

ð

Ł

−

−

Ð

ð

−

−

ð−

ð

ð−

ð−

Ł−

Ð

ð

ð

¼

−

Ðð−

ð

¼

ð−

ð

Ł

Ł

¦

ð

Ł

ð

Ł−

ÿ

¼

Ł

ð

Ł

½

¼

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

¼

ð

ð

¼

¼

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

½

½

ð

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

¼

ð

½

¼

ð

$

%

−

−

[]

() ()

()

()

()

()

()

()

()

()

()

()

()

Score

Tonal

Systems

Score

Tonal

Systems

A - ni - ma me - a tur - ba - ta est tur - ba - ta

est val - de sed tu do - mi - ne

92

97

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 7

Example 7. Reduction of Vicentino, Anima mea (1572), mm. 92–101

274

JOUrNAL of MUSIC ThEOrY

of B throughout the piece. The measures in question contain a chromaticized

variant of an ascending 5–6 sequence, one that creates some significant ana-

lytical problems.

Consider the F≥ in the left hand of m. 44. Is this tone essential or non-

essential? Given the context, it is clearly an alteration of a diatonic FΩ and is

perceived as such if one follows only the voice leading of the various parts.

however, it is a nonessential alteration that has the added effect of correcting

what would otherwise have been a diminished triad, a sonority that composers

still did not generally use in root position and that certainly would not have

had a place in this sequence. If we read the F≥ as an essential chromatic tone,

it should signal at least a temporary change of tonal system, according to the

principles of diatonic reduction outlined above. But I feel it most accurately

adams_08 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:00 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 2 pages

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

Ð

Ð

ý

¦

Ð

ý

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

ý

ý

ý

ý

−

ô

ô

Ð

Ð

ð¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð−

¼

¼

¼

¼

¼

ô

ô

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ð

Ð−

Ð

Ð−

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

Ð

−

−

ð

Ł

ð−

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł−

$

%

!

!

() () ()

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

Ec

Ec

- co

- co

O

O

dol

dol

- ce, o

- ce,

gra -

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 8 page 1 of 2

adams_08 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/4_adams Wed Jul 7 15:00 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 2 of 2 pages

Š

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

Ý

Š

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ł

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ł

¦

Ð

Ł

Ł

Ð

Ł

−

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł−

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

¼

¼

½

¼

¼

½

¼

¼

½

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

ý

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł²

Ł²

Ł¦

ð

ð²

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð²

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

$

%

!

!

() ()

Score

Stage 1

Stage 2

Tonal

Systems

di

o gra - di

- ta

- ta

Vi

Vi

- ta

- ta

del

del

- la

- la mia

mia

vi

vi - ta

- ta

3

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Adams Example 8 page 2 of 2

Example 8. Reduction of Nenna, Ecco, ò dolce, ò gradita (1607), mm. 1–2