Ackerlind Sheila R., Jones-Kellogg Rebecca. Portuguese: A Reference Manual

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Portuguese

x

Personal Pronouns and Possessives .................................................................. 275

Contractions of Direct with Indirect Object Pronouns ...................................... 276

Demonstrative Adjectives and Pronouns, and Contractions .............................. 277

Contractions of Prepositions ............................................................................ 278

Relative Words ................................................................................................ 279

Interrogative Words ......................................................................................... 280

Affirmative and Negative Words...................................................................... 281

Indefinite Words .............................................................................................. 282

Irregular Comparatives and Relative Superlatives ............................................ 284

"Synthetic" Absolute Superlative Adjectives.................................................... 285

Adverbs and Adverb Phrases ........................................................................... 289

Prepositions ..................................................................................................... 297

Verb List................................................................................................................................. 301

Works Consulted

Reference Works ......................................................................................................... 318

Textbooks.................................................................................................................... 320

Index of Topics....................................................................................................................... 321

Index of Portuguese Words and Phrases.................................................................................. 329

THE PORTUGUESE-SPEAKING WORLD

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portuguese: A Reference Manual is designed to be a comprehensive guide for students and

instructors of the language, culture, and literature of the Portuguese-speaking world, as well as

for specialists in other languages who are interested in learning more about the Portuguese

language. It was originally written for university-level students of Portuguese to complement the

few Portuguese-language textbooks available and to supplement the phonetic and grammatical

explanations that those textbooks offered. In recent years, interest in learning Portuguese has

steadily increased and has led to the publication of new textbooks that emphasize the global

nature of the language. This reference manual complements these textbooks as well by

reflecting the Portuguese language as it is currently taught at both the undergraduate and

graduate levels. It provides detailed explanations of the sound and writing systems as well as the

grammar of the principal Portuguese dialects. It also incorporates the new Orthographic Accord

(in effect since 2009–2010), which attempts to standardize Portuguese orthography.

Portuguese is classified as a Romance language because it derives from Latin, the language of

Rome. Following the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in 218 B.C., Latin gradually

evolved into Galician-Portuguese, a language spoken in the Roman provinces of Gallaecia (the

present-day Spanish region of Galicia) and northwestern Lusitania (present-day Portugal).

"Lusitania" has come to be synonymous with "Portugal," and its root word luso has traditionally

signified "Portuguese-speaking" or "related to Portuguese," as in "Lusophone." Over time,

Galician and Portuguese developed into separate dialects. Galician would remain in Galicia, and

Portuguese would extend southward to become the language of all Portugal. During the Age of

Discoveries, fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Portuguese explorers and settlers spread their

language, culture, and religion to Africa, South America, and Asia. Although the influence of

the Portuguese empire waned in the following centuries, the Portuguese language has continued

to thrive; Portuguese is, in fact, the second most spoken Romance language in the world today,

after Spanish.

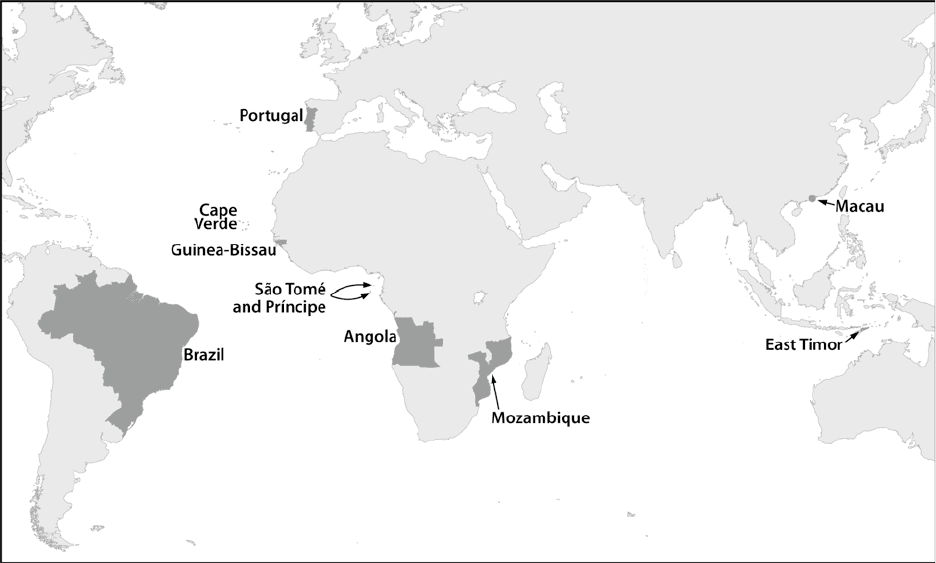

Portuguese is currently the official language of eight countries on four continents—Portugal,

Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, São Tomé and Príncipe, Mozambique, and East

Timor—as well as the co-official language of Macau. These eight countries are also referred to

as the CPLP (Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa), or Community of Portuguese-

Language Countries. An estimated 250 million people in these countries are native speakers of

Portuguese, which is also spoken by several million Portuguese, Brazilians, and Africans living

in immigrant communities throughout the world. Despite the variations in pronunciation,

vocabulary, and grammar which have developed in each country and community, the Portuguese

language continues to unify diverse countries and peoples. The increasing number of students

who study Portuguese at U.S. universities each year attests to the growing importance of the

language, the countries in which it is spoken, and their vibrant culture and literature.

Recent worldwide interest in the Portuguese-speaking world has also been sparked by prestigious

awards granted to three Portuguese speakers: the Nobel Prize for literature in 1998 to the

Portuguese author José Saramago (1922–2010), and the Nobel Peace Prize in 1996 to José

Ramos Horta (1949– ) and Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo (1948– ) for their efforts on behalf of

East Timorese independence.

Portuguese

xiv

There are two principal dialects of Portuguese: European Portuguese (EP), spoken in Portugal,

Lusophone Africa, and East Timor; and Brazilian Portuguese (BP), spoken in Brazil by the vast

majority of Portuguese speakers worldwide. The Portuguese spoken in Brazil, Lusophone

Africa, and East Timor has been influenced to varying degrees by indigenous languages. To

complicate Portuguese dialectology further, pronunciation and even grammar often differ among

and within regions of Portugal and especially of Brazil. Although dialectal and subdialectal

variations abound in Portuguese, we have endeavored to employ "standard" Portuguese

throughout this manual. We define the official standard (padrão) of Portuguese as the form of

the language that is generally acknowledged as the model for the speech and writing of literate

speakers; standard Portuguese is understood by all native speakers, is taught in Lusophone

universities, and is the form of the language presented in traditional Portuguese-language

textbooks for non-native speakers. Because standard Portuguese unifies countries and peoples,

learning standard Portuguese enables a non-native speaker to communicate effectively in any

Portuguese-speaking country or community.

Although we use standard Portuguese grammar in the examples, we also address frequently used

variations of "colloquial" Portuguese, a term that we define as informal, unmonitored speech and

written communication (email, blogs, etc.) in which content matters more than correct form. We

occasionally footnote the term nonstandard Portuguese when we refer to those usages of slang

and colloquial speech that do not follow traditional grammar rules and are considered incorrect

in standard Portuguese. We caution the reader about using colloquialisms before learning their

nuances, however, since colloquialisms uttered by a non-native speaker might seem strange,

inappropriate, or even offensive to a native speaker; in addition, a native speaker of one

Portuguese dialect might misunderstand a colloquialism of another dialect.

We define the term formal Portuguese as monitored speech and texts in which both content and

correct form are important and expected by the listener or reader (communiqués, reports,

scholarly articles and books, etc.). We occasionally use the term literary to refer to classical

written works, which tend to have a more formal structure, and archaic to refer to those elements

of Portuguese that are no longer used in either formal or colloquial Portuguese but that appear in

literary texts written from the Middle Ages to the nineteenth century. In order to assist students

to read these texts, this manual includes archaic forms, which are often excluded from

Portuguese textbooks (and even grammars of modern Portuguese) because they are not

frequently used in colloquial Brazilian Portuguese. By becoming familiar with more formal and

even archaic Portuguese, students will be able to recognize the structures that native speakers

recognize as a result of having heard them in formal speeches and read them in literary works.

In accordance with the general tendency of Portuguese-language instruction in the United States

since the end of World War II, we give preference to Brazilian vocabulary and grammar when

European Portuguese variants occur. However, our intent is not to focus entirely on Brazilian

Portuguese—which other books have already done—but also to incorporate variants of the

language that are often found in Portugal, and consequently, in Lusophone African countries. By

including these variants, we hope to provide a more complete description of the Portuguese

language. Newer textbooks of Portuguese are likewise addressing non-Brazilian as well as

Brazilian Portuguese, and this trend is common in postgraduate Portuguese studies.

Preface and Acknowledgments

xv

We begin the manual with an explanation of the various abbreviations and symbols used

throughout the book so that readers can become familiar with the terminology before

encountering it in a particular section. Most of our phonetic symbols adhere to the International

Phonetic Alphabet; the minor variations are intended to simplify an alphabet that might

otherwise be confusing to nonlinguists. In addition to defining the linguistic and grammatical

terms that we use, we provide a list of linguistic and grammatical terms in English and

Portuguese so that readers will better understand the Portuguese terminology that their textbooks

occasionally use. We have simplified the terminology used in the manual without excluding any

information necessary for beginning-level learners to understand a particular concept. We use

technical terminology only when necessary, and in those cases we provide definitions and/or

explanations. In the last part of the front section, we outline the principal changes in Portuguese

orthography as codified in the recent Orthographic Accord; by implementing these changes,

readers will be able to write Portuguese in its most up-to-date form.

Since we expect that the Portuguese-language learners who use this book will generally have an

English and/or Spanish language background, we employ the methodology of contrastive

analysis, which we have found essential in teaching a foreign language to learners who already

speak a sister language (in this case, Spanish) or a cousin language (English). By comparing and

contrasting Portuguese patterns with those found in Spanish and English, we address a range of

issues that students may encounter while learning Portuguese.

The "Sound System" section provides a description of the most common sounds found in

Brazilian and European Portuguese, sounds that all Portuguese speakers recognize regardless of

their dialect; consequently, a learner could emulate these sounds without risk of being

misunderstood in either dialect. We have chosen not to focus exclusively on the sounds of either

Brazilian or European Portuguese, nor do we attempt to give their subdialectal variations, which

books specifically written about dialectology have effectively done. We do pay special attention

to nasal vowels and diphthongs, which are a distinctive feature of Portuguese pronunciation.

The "Writing System and Accentuation" section begins with a description of the letters used to

transcribe Portuguese sounds. Once we identify the sound or sounds associated with each

individual letter, we compare and contrast the Portuguese letters or letter sequences with those

used in Spanish and English. After describing Portuguese punctuation and diacritical marks, we

discuss the Portuguese system of written accentuation, which differs considerably from the

Spanish system.

The "Cognates" section shows how to recognize and form cognates by learning and applying the

patterns that correspond between Portuguese, Spanish, and English; students who learn and apply

these patterns can dramatically and easily increase their vocabulary. The chapter on true, partial,

and false cognates gives advanced-level students the opportunity to see how or why they might

be cross-contaminating Portuguese with Spanish and/or English.

The greater part of this manual is devoted to grammar. We address the grammatical topics found

in current Portuguese textbooks, and we endeavor to provide cohesive and concise explanations

that address the issues associated with these topics. Since we consider Portuguese a single

language, with dialectal variants that learners should recognize, we emphasize the commonalities

Portuguese

xvi

of Portuguese grammar. When a European Portuguese variant occurs, we adhere to Brazilian

Portuguese usage, but we clearly state the variant either in a footnote or in parentheses. We do

make the assumption—admittedly problematic—that European variants tend to apply to the

Portuguese spoken in Lusophone Africa.

Throughout this manual, in both the text and the footnotes, we offer explanations of issues

commonly discussed in the language classroom. They include (a) Portuguese phonetics, word

formation, and grammar; (b) comparative/contrastive Portuguese, Spanish, and English

phonetics, word formation, and grammar; and (c) Portuguese etymology and historical

linguistics. Numerous "Notes to Spanish Speakers" are included to highlight significant

differences between Portuguese structures and their Spanish counterparts. Also included are

details on historical linguistics, which we have found through classroom experience especially

useful for learners who have studied Latin or another Romance language and who have questions

concerning the evolution of Portuguese (and Spanish) from Latin.

Since this manual is intended for beginning as well as advanced learners of Portuguese, we

provide extensive verb charts to complement material found in most textbooks. The charts are

arranged not only by verb but also by verb tense, and they should be especially useful for

beginning-level students, who must often understand the patterns of a tense before they are able

to apply them to a particular verb. These charts can serve equally well as a reference tool for

instructors. We also include other grammar charts (on pronouns, adverbs, prepositions, etc.), as

well as a list of all verbs used or mentioned in the text, footnotes, and charts—including certain

rather obscure verbs that exemplify rare or archaic grammatical points.

For readers who would like to continue their studies by specializing in one particular dialect of

Portuguese, we provide at the end of the book a list of reference works.

We would like to thank our colleagues in the Department of Foreign Languages at the United

States Military Academy (West Point)—in particular, the Portuguese Section—for their support

and collegiality. We are grateful to the following current and former Brazilian exchange officers

assigned to West Point for their invaluable help in proofreading the manuscript: Maj. Gen.

Floriano Peixoto Vieira Neto, Maj. Gen. Luiz Guilherme Paul Cruz, and Lt. Col. Fernando

Civolani Lopes. We are also grateful to two former visiting professors at the Academy, John B.

Jensen (Florida International University) and Antônio R. M. Simões (Kansas University), for

their insightful and constructive comments. We also extend our thanks to Geri Smith (French

Section) and Laura Vidler (Spanish Section) for their encouragement and assistance during the

revision process. We would like to thank the University of Texas Press for its dedication to

publishing monographs in the field of foreign languages, Jim Burr (Humanities Editor) and

Victoria Davis (Manuscript Editor) for their professionalism and promptness in responding to

myriad questions, and Sheila Berg for her thoroughness in copy-editing the manuscript.

It is our hope that this manual will be a useful reference tool to readers who are learning the

Portuguese language and mastering its complexities.

SRA and RJK

15 August 2010

ABBREVIATIONS, SYMBOLS, AND DIACRITICAL MARKS

ABBREVIATIONS

NONPHONETIC SYMBOLS

adj.

adjective

=

to be identical / equivalent to

adv.

adverb

<

to develop / derive from

aff.

affirmative

>

to develop into / change (in)to / become

BP

Brazilian Portuguese

cat.

category

conj.

conjugation(s)

def.

definite

DIACRITICAL (= ACCENT) MARKS

demonstr.

demonstrative

dir.

direct

´

(á)

acute accent

Eng.

English

¸

(ç)

cedilla

EP

European Portuguese

ˆ

(â)

circumflex

f / fem.

feminine

¨

(ü)

dieresis (no longer used in Portuguese)

gram.

grammatical

`

(à)

grave accent

indef.

indefinite

˜

(ã)

tilde

indic.

indicative

(See pp. 22–23 for details on how these

indir.

indirect

marks are used.)

interrog.

interrogative

invar.

invariable

irreg.

irregular

lett.

letter(s)

m / masc.

masculine

math.

mathematical

neg.

negative

obj.

object

orth.

orthographic

part.

participle

pers.

person

plur.

plural

Port.

Portuguese

prep.

preposition / prepositional

pres.

present

pron.

pronoun

refl.

reflexive

reg.

regular

sing.

singular

snd.

sound(s)

Sp.

Spanish

subj.

subject // subjunctive

sym.

symbol

var.

variable

vs.

versus

PHONETIC SYMBOLS

1

SYMBOL

EXAMPLES

VOWELS

ORAL

[a]

gato / sofá // lava (BP)

[ɐ]

2

lava // -amos (EP)

[ɨ]

bebe / beber (EP)

[i]

fica / rubi // bebe (BP)

[e]

bebo / sê / você

(closed

e)

[ɛ]

bebe / Sé / pé

(open

e)

[ɔ]

roda / pode / avó

(open

o)

[o]

rodo / pôde / avô

(closed

o)

[u]

lua / peru / lavo

NASAL

[ɐ̃]

irmã / samba / canta

[ĩ]

jardim / pinto

[ẽ]

lembro / mente

[õ]

marrom / ponto

[ũ]

algum / fundo

SEMIVOWELS

3

ORAL

[

i

]

pai / sei / foi / sóis

[

u

]

seu / sou // língua / qual //

alto / hotel (BP)

NASAL

[

ĩ

]

mãe / limões

[

ũ

]

mão / limão

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1

Most phonetic symbols used in this book are those of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA);

the few non-IPA symbols might be more accessible to a nonlinguist than their IPA counterparts.

All phonetic symbols except /R/ are enclosed in brackets [ẽ

ĩ

]; alphabet letters are italicized (em).

The sounds represented by these symbols are described on pp. 1–10.

2

BP: Unstressed [ɐ] is a variant of [a], with which it alternates only in word-final position (lava).

EP: [ɐ] is found in all unstressed positions (lavar / lâmpada / lava);

stressed [ɐ] is the sound of the -a in the 1st-pers. plur. present indicative ending -amos.

3

Antônio R. M. Simões uses these commonsense phonetic symbols for semivowels in his Pois Não;

IPA symbols for [

i

] / [

u

] are [j] / [w], respectively.

Phonetic Symbols

xix

SYMBOL

EXAMPLES

CONSONANTS

[p]

popular / apreciar

[b]

bebo / nobre

[β]

bebo

(EP: variant of [b])

[t]

teto / três / alto

[tš]

1

ritmo / tio / noites

(BP: variant of [t])

[d]

dedo / drama / aldeia

[dž]

1

dia / pede

(BP: variant of [d])

[ð]

dedo

(EP: variant of [d])

[k]

coca / acredito //

que / conquista

[g]

gago / grande / guerra

[γ]

gago / águia

(EP: variant of [g])

[f]

fofo / África

[v]

viver / lavrador

[s]

sol / isso / cem / dança

[z]

zero / rapazes / casa

[š]

2

cheiro / xícara / baixo

[ž]

2

janta / geral / agir

[m]

cama / mima

[n]

cana / nono

[ɲ]

3

canha / minha

[l]

lado / fala

[ł]

alto / hotel

(EP: variant of [l])

[λ]

olho / milhão / lhes

[ɾ]

caro / trem / nobre

/R/

rosa / honra / carro

NOTE: this book uses the symbol /R/ to include the

variant sounds transcribed by letters rr and occasionally r;

the most common of these sounds are as follows:

[h]

(similar to Eng. ahoy)

[x]

(similar to Sp. ojo)

[R]

4

(similar to a voiced gargling sound)

[r]

4

(similar to Sp. carro)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1

IPA symbols for [tš] / [dž] are [ʧ] / [ʤ], respectively.

2

IPA symbols for [š] / [ž] are [ʃ] / [ʒ], respectively.

3

Simões uses the phonetic symbol [ŋ] for Port. nh to indicate that the sound is produced farther

back in the palate than the sound represented by [ɲ] (the traditional symbol used for Port. nh as well

as Sp. ñ). Simões also accepts the symbol [ỹ] since Port. nh is normally produced with the tongue

barely touching the roof of the mouth (Pois Não 424n3); in effect, minha is pronounced [mĩỹa].

Mário A. Perini considers nh to be a nasal semivowel (not a true consonant)

(Modern Portuguese 13).

4

These voiced variant sounds are less common in BP than in EP (in which [R] predominates).