Yamaguchi H. Engineering Fluid Mechanics (Fluid Mechanics and Its Applications)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

40 1 Fundamentals in Continuum Mechanics

1-6.

Obtain components

xx

T ,

xy

T and

xz

T of tensor T.

Ans.

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

¬

ª

ki

ji

ii

T

T

T

xz

xy

xx

T

T

T

1-7.

Show that the velocity gradient tensor u does not satisfy the princi-

ple of frame invariance.

Ans.

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

¬

ª

w

w

w

w

w

w

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

w

w

.oftiontransfortalinearnotis

and,

0

0

00

0

0

00

0

0

0

QQQ

QQ

QQQQ

QQ

QQ

QQQ

*

uu

u

u

x

x

x

x

x

u

u

xuu

x

x

xxxx

T

T

TT

rr

r

r

T

r

r

T

r

:

:

Nomenclature

A

: material parameter

a

: acceleration

C

: Cauchy strain tensor

-1

C

: Finger tensor

E

: displacement gradient tensor

e

: rate of strain tensor

i

e

ˆ

: unit base vector

kj,i,

1-5. Verify that the Finger tensor defined in Eq. (1.4.4),

T111

i.e.

EEC

is symmetric. Consider

E in the Cartesian coordinates system.

Ans.

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

«

¬

ª

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

¨

©

§

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

k

X

j

x

k

X

i

x

T

kj

E

ik

E

ij

C

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

i

X

j

x

T

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

X

x

j

X

i

x

T

111

3

3

3

2

3

1

2

3

2

2

2

1

1

3

1

2

1

1

3

3

2

3

1

3

3

2

2

2

1

2

3

1

2

1

1

1

1

111

E,E

EEC

–1

1

ji

ee

ˆˆ

: unit dyad

F

: force

g

: body force

g

: gravitation acceleration

I

: unit tensor

J

: Jacobian

L

: material line element

i

L

: Intermediate scale

l

L

: large scale

m

L

: molecular scale

n

ˆ

: unit normal vector

p

: pressure

Q

: rotation tensor

S

: general second order tensor

S

: surface area

T

: total stress tensor

n

t

: stress vector

t

: time

u

: velocity

x

: position vector in vector space

: Knudsen number

ij

G

: Kronecker delta

İ

: (polyadic) alternator

ijk

H

: Eddington notation

O

: eigenvalue

I

: scalar potential

: angular velocity

Ȧ

: spin tensor

Ȧ

: vorticity vector

Bibliography

The content in this chapter is standard matter and treated in almost all texts.

The mathematical methods in accounting Cartesian vectors and tensors are

found in

1. A. Rutherford, Vectors, Tensors, and the Basic Equations of Fluid Me-

chanics

, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1962.

*

:

Bibliography 41

42 1 Fundamentals in Continuum Mechanics

2. F. B. Hildebrand, Advanced Calculus for Applications (2nd Edition),

Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1976.

3.

R. B. Bird, C. F.Curtiss, R. C. Armstrong and O. Hassanger, Dynamics

of Polymeric Liquids

(2nd Edition), John Wiley & Sons, A Wiley-

Interscience Publication, New York, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, 1987. Appen-

dices are useful.

4.

G. B. Arfken and H. J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists

(6th Edition), Elsevier, Academic Press, Amsterdam, 2005.

Some interesting topics on microhydrodynamics are found in

5. S. Kim and S. J. Karrila, Microhydrodynamics, Principles and Selected

Applications

, Butterworth-Heinemann, a division of Reed Publishing

(U.S.A.) Inc., Oxford, London, 1991.

6.

P. Tabeling, Introduction to Microfluidics, Oxford University Press

Inc., New York, 2005.

2. Conservation Equations in Continuum

Mechanics

Sir Isaac Newton was the first to correctly state the basic laws governing

the motion of a particle and to demonstrate their validity. The dynamics of

continuum uses the concept of a particle, called the fluid particle, which

follows Newton’s second law of motion. In continuum mechanics, they are

written in the form of conservation equations. In this chapter, the basic

forms of conservation laws are introduced to mass, linear momentum, an-

gular momentum and energy. One of which is Cauchy’s equation, which is

equivalent to Newton’s second law of motion. These conservation equa-

tions are unconstituted; however, later chapters looking at specific types of

fluid flow will consider constituted equations as well.

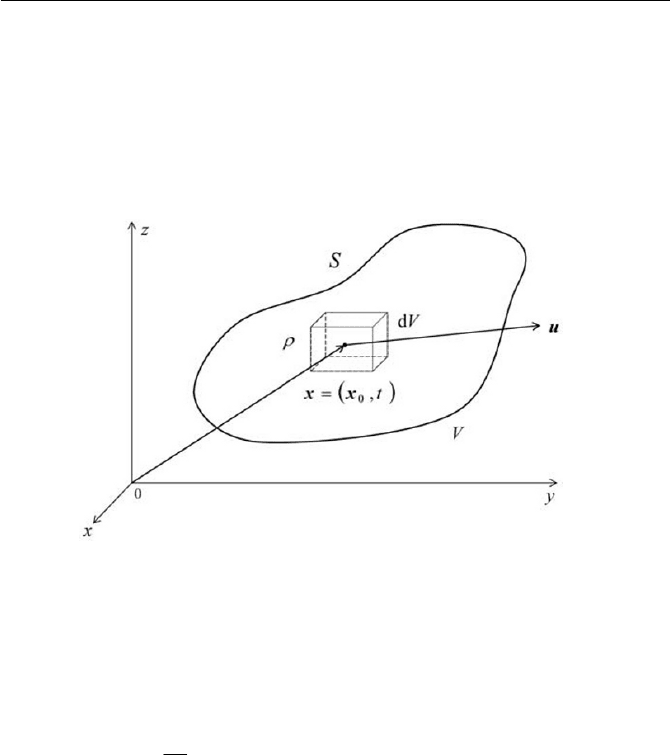

2.1 Mass Conservation

Let us begin to consider the flow system of a continuum medium, which

consists of fluid particles. A fluid particle, that moves with a velocity u

and has the density

t),(x

U

at position ),(

0

txxx , is a representative ob-

ject of the medium, having the mass of finite volume

V

. The mass of the

fluid particle can be obtained, see Fig. 2.1, using volume integral by

³

V

dVm

U

(

2.1.1)

If we postulate that there are no sources or sinks in the medium, the

mass of the fluid particle does not change in position and time, i.e. the

mass is conserved in space and time as follows

0

³

V

dV

Dt

D

Dt

Dm

U

(

2.1.2)

By setting

F

as

U

F in the Reynolds’ transport theorem given by Eq.

(1.5.8), we have

43

44 2 Conservation Equations in Continuum Mechanics

0

»

¼

º

«

¬

ª

³

V

dV

Dt

D

u

U

U

(

2.1.3)

Since the volume of the fluid particle is arbitrary, the volume integral in Eq.

(2.1.3) can be made to vanish in an identical manner from the fluid system

of the continuum, which gives

0 u

U

U

Dt

D

(

2.1.4)

Equation (2.1.4) can be further expanded, using the definition of the mate-

rial derivative of Eq. (1.1.7) to give

0

w

w

u

U

U

t

(

2.1.5)

Equations (2.1.4) and (2.1.5) are both called the equation of continuity (or

the continuity equation). Considering the nature of derivation and for the

sake of distinguishing between the two, Eq. (2.1.4) is often called the non-

conservation form of the continuity equation, and Eq. (2.1.5) is called the

conservation form of the continuity equation.

u

U

in Eq. (2.1.5) is identi-

fied as the mass flux.

If the medium of continuum is incompressible, the density

U

of each

material point

x

is kept constant with respect to time t . This will lead Eq.

(2.1.4) to a form, setting

0 DtD

U

, as follows

0 u

(

2.1.6)

The flow field described by Eq. (2.1.6) is called the solenoidal velocity

field. When, in fact, the flow of a medium is incompressible, the flow is an

isotropic flow, in which pressure change does not affect its density.

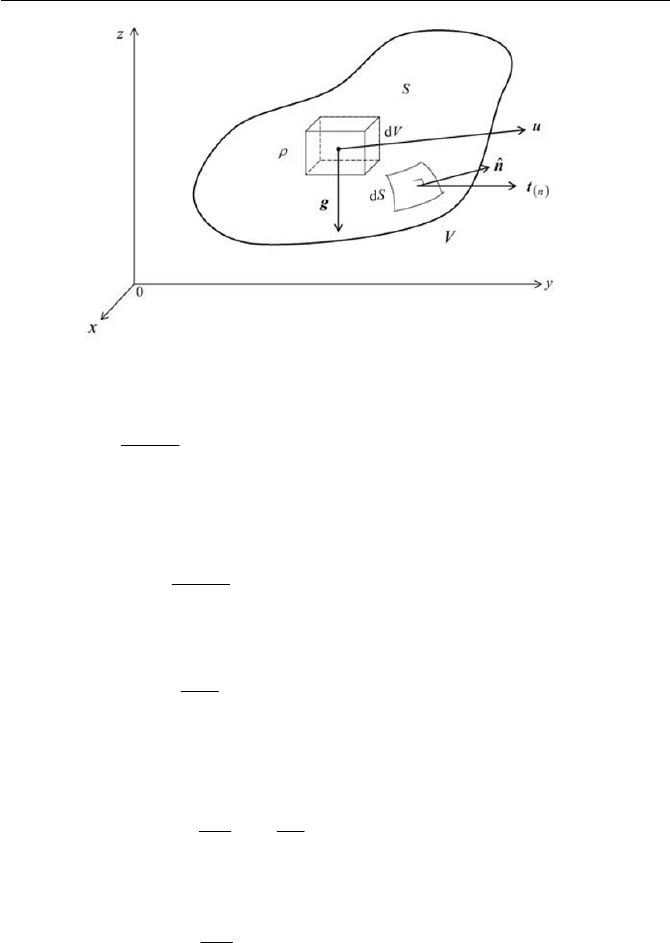

2.2 Linear Momentum Conservation

Studying the dynamics of flow in a continuous medium requires the forces

acting on a fluid particle and the acceleration of the fluid particle to be in

an inertial frame of reference. The law that governs the dynamic motion

of continuum medium is given by the conservation of linear momentum.

Note that “linear” is understood as the motion of a particle in the direc-

tion of the acceleration, and is used in order to distinguish it from the

“angular” momentum. Below we have shown two kinds of forces seen

when in dealing with the motion of a continuum medium. As previously

2.2 Linear Momentum Conservation 45

descried in Section 1.6, they are surface forces, representatively written as

d

n

St

for a surface element

ˆ

dSn

, and body forces, similarly expressed

dV

U

g for a volume element dV. The linear momentum at a position of

t,

0

xxx

can be written dV

U

u for a volume element inside the finite

volume of the fluid particle.

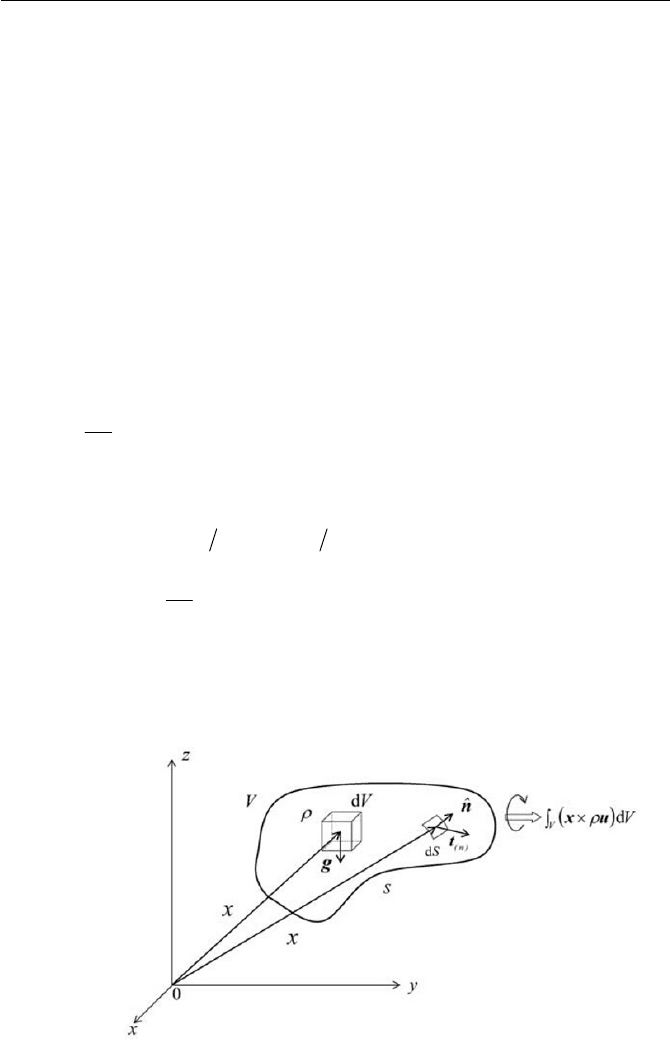

Fig. 2.1 A fluid particle moving with velocity

u

The volume element, the density of which is

U

, is in motion with a ve-

locity of u, as shown in Fig. 2.2. The conservation of the linear momen-

tum of the fluid particle can be written

ddd

n

VSV

D

VS

V

Dt

UU

³³³

ut g

(

2.2.1)

where the left hand side of Eq. (2.2.1) represents the change of linear mo-

mentum, and the first term of the right hand side of Eq. (2.2.1) corresponds

to the net surface force and the second term signifies the net body force

acting on the fluid particle. This is an integral form of the equation of mo-

tion, derived from the principle of the conservation of linear momentum.

The equation of (2.2.1) can be changed by considering Cauchy’s stress

formula given by Eq. (1.6.8) and can be reduced into the volume integral

form, using Gauss’ divergence theorem. After applying Reynolds’ transport

theorem from Eq. (1.5.8) to the change of linear momentum, specifically

setting uF

U

in Eq. (2.2.1), we can obtain the conservation of linear

momentum in volume integral form

46 2 Conservation Equations in Continuum Mechanics

Fig. 2.2 Force acting on a fluid

³³³

¿

¾

½

¯

®

VVV

dVdVdV

Dt

D

guu

u

UU

U

Tේේ

(2.2.2)

However, since the volume V of the fluid particle is arbitrary, this equation

is only satisfied if

guu

u

UU

U

Tේේ

Dt

D

(

2.2.3)

which can alternatively be expressed

guu

u

UU

U

w

w

Tේේ

t

(

2.2.4)

Considering the continuity equation, Eq. (2.2.4), where uu

U

is called the

linear momentum flux, can be re-arranged as Eq. (2.1.5)

guu

u

UU

U

U

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

w

w

Tේේ

tDt

D

(2.2.5)

and thus

g

u

UU

Tේ

Dt

D

(

2.2.6)

The Eq. (2.2.6) is called Cauchy’s equation of motion. The equation is

valid for any continuum when the stress tensor

T and the body force

g

U

2.3 Angular Momentum Conservation 47

are specified. It should be noted that the body force of gravity furnishes an

example of g for problems we consider in the text. Equation (2.2.6) can

be further reduced to a form, using the definition of the substantial deriva-

tive given by Eq. (1.1.7) as follows

guu

u

UU

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

w

w

Tේේ

t

(2.2.7)

Again considering the nature of derivation, and to clearly distinguish

between Eqs. (2.2.4) and (2.2.7), Eq. (2.2.4) is often called the conserva-

tion form of the linear momentum and Eq. (2.2.7) the non-conservation

form of the linear momentum.

If the continuum is incompressible, i.e.

0=u , and we take the rota-

tion, i.e. u ( ), of each of the terms in Eq. (2.2.7), we can then obtain

Tu

w

w

uȦȦu

Ȧ

UUU

t

(

2.2.8)

Equation (2.2.8) is called the vorticity transport equation. The advantage of

using Eq. (2.2.8) is that the gravitational acceleration g , where

z

e

ˆ

g

g ,

can be eliminated in the same way, if the force can be identified as a

x gȡpp

*

, with the pressure gradient

gȡpp

*

. As a result of this reduction, Eq. (2.2.8) may be expressed

in the following form

IJu

w

w

uȦȦu

Ȧ

ȡȡ

t

ȡ

(

2.2.9)

where IJ is the deviatoric stress tensor, as introduced in Eq. (1.6.13). Equa-

tion (2.2.9) is particularly useful when a velocity field is described by a

stream function. In this case, the system of flow can be expressed with a

component of the vorticity vector normal to the flow plane and the stream

function. The terms appearing in the left hand side of Eqs. (2.2.8) and

(2.2.9) in kinematics of Ȧ are respectively the transient term, the convec-

tive term and the straining term.

2.3 Angular Momentum Conservation

Some continuum while in motion are strongly effected by an external field.

As such, the angular momentum per unit mass does not simply equate to

the moments of the linear momentum per unit mass. This is particularly

potential force, such that

48 2 Conservation Equations in Continuum Mechanics

true when there are other torques, which are not part of the moments of

force, appearing in the linear momentum equation. Such material of con-

tinuum is called polar material. Within the frame of the continuum me-

chanic, speaking in general terms, we will derive a conservation equation

of angular momentum. Before proceeding to the polar fluid, we will exam-

ine non-polar fluid in great detail, so that its properties and character are

clearly understood.

We shall designate

dVux

U

u as the angular momentum of a volume

element in a fluid particle while

dVgx

U

u and

dS

n

txu are torques due

to body force and surface force respectively. Next, applying the conserva-

tion law to these forces, it suggests that the net change of the angular mo-

mentum is equal to the net torque acting upon the fluid particle, see Fig.

2.3. The conservation equation of the angular momentum can be thus writ-

ten as follows

³³³

uu u

S

n

VV

dSdVdV

Dt

D

txgxux

UU

(

2.3.1)

With the aid of the Reynolds’ transport theorem of Eq. (1.5.8) and the con-

tinuity equation of Eq. (2.1.5), setting uxF u and using the relation

0 u uu and

dtdDtD uxux u u , we have

³³³

uu

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

u

VS

n

V

dSdVdV

dt

d

txgx

u

x

UU

(2.3.2)

The second term of the right hand side of Eq. (2.3.2) can be further re-

duced to the following forms, using Cauchy’s stress formula given by Eq.

(1.6.8).

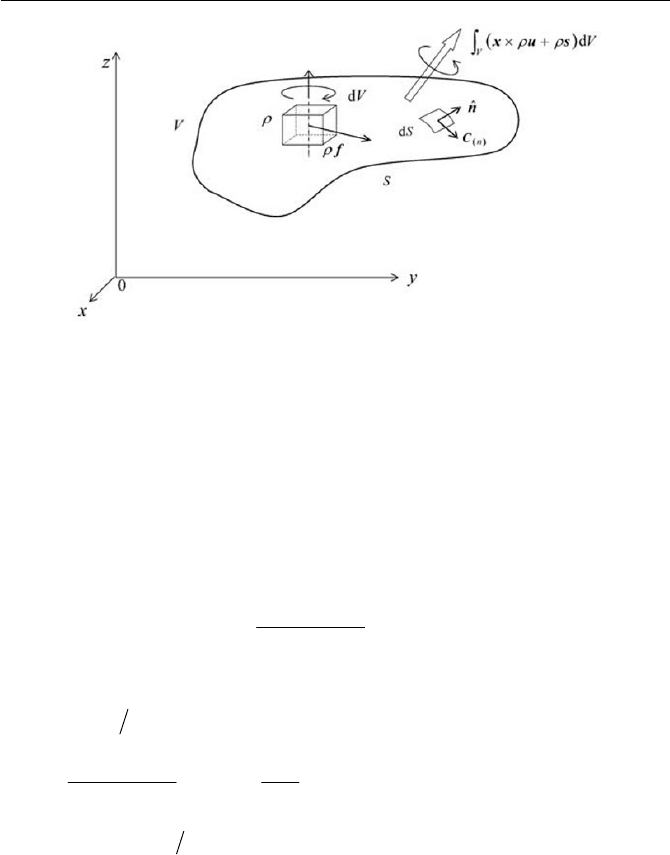

Fig. 2.3 Torques due to body force and surface force

2.3 Angular Momentum Conservation 49

Fig. 2.4 Body couple and surface couple

dV

dSdSdS

V

SSS

n

³

³³³

u

u

u

u

x

x

n

x

n

tx

T

T

ˆ

T

ˆ

(

2.3.3)

Here, we used the polyadic alternator

kijkji

ˆˆˆ

eee

H

u and the Gauss’ diver-

gence theorem, shown as

^

`

³³

w

w

V

l

lkjijk

S

lkljijk

dV

x

Tx

SdnTx

H

H

(2.3.4)

Furthermore, it will be shown that the i th component of

xu T , i.e.

^

`

llkjijk

xTx

H

, can be expressed by the following relations

^

`

Ax u

w

w

w

w

T

jkijk

l

lk

jijk

l

lkjijk

T

x

T

x

x

Tx

HH

H

(2.3.5)

where we used

jllj

xx

G

ww . The vector A in Eq. (2.3.5) is a pseudovec-

tor, which has these components of the skew-symmetric part of the stress

tensor

T , which is demonstrated here as

332211211231331232231

AAATTTTTT eeeeeeA

ˆˆˆˆˆˆ

(

2.3.6)

where the components of A are derived from the matrix