Whetten David A., Cameron Kim S. Developing management skills

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS CHAPTER 2 107

______ ______ 9. I encourage others to generate recommended solutions, not just questions, when

they come to me with problems or issues.

______ ______ 10. I strive to redefine problems as opportunities for improvement.

TIME MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT

In responding to the statements below, fill in each blank with the number from the rating

scale that indicates the frequency with which you do each activity. Assess your behavior

as it is, not as you would like it to be. How useful this instrument will be to you depends

on your ability to accurately assess your own behavior.

Please note that the first section of the instrument can be completed by anyone. The

second section applies primarily to individuals currently serving in a managerial position.

Turn to the end of the chapter to find the scoring key and an interpretation of your

scores.

Rating Scale

0 Never

1 Seldom

2 Sometimes

3 Usually

4 Always

Section I

______ 1. I read selectively, skimming the material until I find what is important, then high-

lighting it.

______ 2. I make a list of tasks to accomplish each day.

______ 3. I keep everything in its proper place at work.

______ 4. I prioritize the tasks I have to do according to their importance and urgency.

______ 5. I concentrate on only one important task at a time, but I do multiple trivial tasks at

once (such as signing letters while talking on the phone).

______ 6. I make a list of short five- or ten-minute tasks to do.

______ 7. I divide large projects into smaller, separate stages.

______ 8. I identify which 20 percent of my tasks will produce 80 percent of the results.

______ 9. I do the most important tasks at my best time during the day.

______ 10. I have some time during each day when I can work uninterrupted.

______ 11. I don’t procrastinate. I do today what needs to be done.

______ 12. I keep track of the use of my time with devices such as a time log.

______ 13. I set deadlines for myself.

______ 14. I do something productive whenever I am waiting.

______ 15. I do redundant “busy work” at one set time during the day.

______ 16. I finish at least one thing every day.

______ 17. I schedule some time during the day for personal time alone (for planning, meditation,

prayer, exercise).

______ 18. I allow myself to worry about things only at one particular time during the day, not

all the time.

______ 19. I have clearly defined long-term objectives toward which I am working.

______ 20. I continually try to find little ways to use my time more efficiently.

108 CHAPTER 2 MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS

Section II

______ 1. I hold routine meetings at the end of the day.

______ 2. I hold all short meetings standing up.

______ 3. I set a time limit at the outset of each meeting.

______ 4. I cancel scheduled meetings that are not necessary.

______ 5. I have a written agenda for every meeting.

______ 6. I stick to the agenda and reach closure on each item.

______ 7. I ensure that someone is assigned to take minutes and to watch the time in every

meeting.

______ 8. I start all meetings on time.

______ 9. I have minutes of meetings prepared promptly after the meeting and see that follow-

up occurs promptly.

______ 10. When subordinates come to me with a problem, I ask them to suggest solutions.

______ 11. I meet visitors to my office outside the office or in the doorway.

______ 12. I go to subordinates’ offices when feasible so that I can control when I leave.

______ 13. I leave at least one-fourth of my day free from meetings and appointments I can’t

control.

______ 14. I have someone else who can answer my calls and greet visitors at least some of

the time.

______ 15. I have one place where I can work uninterrupted.

______ 16. I do something definite with every piece of paper I handle.

______ 17. I keep my workplace clear of all materials except those I am working on.

______ 18. I delegate tasks.

______ 19. I specify the amount of personal initiative I want others to take when I assign them

a task.

______ 20. I am willing to let others get the credit for tasks they accomplish.

TYPE A PERSONALITY INVENTORY

Rate the extent to which each of the following statements is typical of you most of the

time. Focus on your general way of behaving and feeling. There are no right or wrong

answers. When you have finished, turn to the end of the chapter to find the scoring key

and an interpretation of your scores.

Rating Scale

3 The statement is very typical of me.

2 The statement is somewhat typical of me.

1 The statement is not at all typical of me.

_______ 1. My greatest satisfaction comes from doing things better than others.

_______ 2. I tend to bring the theme of a conversation around to things I’m interested in.

_______ 3. In conversations, I frequently clench my fist, bang on the table, or pound one fist

into the palm of another for emphasis.

_______ 4. I move, walk, and eat rapidly.

MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS CHAPTER 2 109

_______ 5. I feel as though I can accomplish more than others.

_______ 6. I feel guilty when I relax or do nothing for several hours or days.

_______ 7. It doesn’t take much to get me to argue.

_______ 8. I feel impatient with the rate at which most events take place.

_______ 9. Having more than others is important to me.

_______ 10. One aspect of my life (e.g., work, family care, school) dominates all others.

_______ 11. I frequently regret not being able to control my temper.

_______ 12. I hurry the speech of others by saying “Uh huh,” “Yes, yes,” or by finishing their

sentences for them.

_______ 13. People who avoid competition have low self-confidence.

_______ 14. To do something well, you have to concentrate on it alone and screen out all distrac-

tions.

_______ 15. I feel others’ mistakes and errors cause me needless aggravation.

_______ 16. I find it intolerable to watch others perform tasks I know I can do faster.

_______ 17. Getting ahead in my job is a major personal goal.

_______ 18. I simply don’t have enough time to lead a well-balanced life.

_______ 19. I take out my frustration with my own imperfections on others.

_______ 20. I frequently try to do two or more things simultaneously.

_______ 21. When I encounter a competitive person, I feel a need to challenge him or her.

_______ 22. I tend to fill up my spare time with thoughts and activities related to my work (or

school or family care).

_______ 23. I am frequently upset by the unfairness of life.

_______ 24. I find it anguishing to wait in line.

SOURCE: Tolerance of Ambiguity Scale, S. Budner (1962), “Intolerance of Ambiguity as a Personality Variable,”

from Journal of Personality, 30: 29–50. Reprinted with the permission of Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.

SOCIAL READJUSTMENT RATING SCALE*

Circle any of the following you have experienced in the past year. Using the weightings at

the left, total up your score.

Mean Life

Value Event

87 1. Death of spouse/mate

79 2. Death of a close family member

78 3. Major injury/illness to self

76 4. Detention in jail or other institution

72 5. Major injury/illness to a close family member

71 6. Foreclosure on loan/mortgage

71 7. Divorce

70 8. Being a victim of crime

69 9. Being a victim of police brutality

*This assessment is not available online.

110 CHAPTER 2 MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS

69 10. Infidelity

69 11. Experiencing domestic violence/sexual abuse

66 12. Separation or reconciliation with spouse/mate

64 13. Being fired/laid-off/unemployed

62 14. Experiencing financial problems/difficulties

61 15. Death of a close friend

59 16. Surviving a disaster

59 17. Becoming a single parent

56 18. Assuming responsibility for sick or elderly loved one

56 19. Loss of or major reduction in health insurance/benefits

56 20. Self/close family member being arrested for violating the law

53 21. Major disagreement over child support/custody/visitation

53 22. Experiencing/involved in an auto accident

53 23. Being disciplined at work/demoted

51 24. Dealing with unwanted pregnancy

50 25. Adult child moving in with parent/parent moving in with adult child

49 26. Child develops behavior or learning problem

48 27. Experienced employment discrimination/sexual harassment

47 28. Attempting to modify addictive behavior of self

46 29. Discovering/attempting to modify addictive behavior of close family member

45 30. Employer reorganization/downsizing

44 31. Dealing with infertility/miscarriage

43 32. Getting married/remarried

43 33. Changing employers/careers

42 34. Failure to obtain/qualify for a mortgage

41 35. Pregnancy of self/spouse/mate

39 36. Experiencing discrimination/harassment outside the workplace

39 37. Release from jail

38 38. Spouse/mate begins/ceases work outside the home

37 39. Major disagreement with boss/coworker

35 40. Change in residence

34 41. Finding appropriate child care/day care

33 42. Experiencing a large unexpected monetary gain

33 43. Changing positions (transfer, promotion)

33 44. Gaining a new family member

32 45. Changing work responsibilities

30 46. Child leaving home

30 47. Obtaining a home mortgage

30 48. Obtaining a major loan other than home mortgage

MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS CHAPTER 2 111

28 49. Retirement

26 50. Beginning/ceasing formal education

22 51. Receiving a ticket for violating the law

Total of Circled Items: _________

SOURCE: Social Readjustment Rating Scale, Hobson, Charles Jo, Joseph Kaen, Jane Szotek, Carol

M. Nethercutt, James W. Tiedmann and Susan Wojnarowicz (1998), “Stressful Life Events:

A Revision and Update of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale,” International Journal of

Stress Management, 5: 1–23.

SOURCES OF PERSONAL STRESS

1 Identify the factors that produce the most stress for you right now. What is it that creates

feelings of stress in your life?

Source of Stress Rating

2 Now give each of those stressors above a rating from 1 to 100 on the basis of how powerful

each is in producing stress. Refer to the Social Readjustment Rating Scale for relative

weightings of stressors. A rating of 100, for example, might be associated with the death of

a spouse or child, while a rating of 10 might be associated with the overly slow driver in

front of you.

3 Use these specific sources of stress as targets as you discuss and practice the stress

management principles presented in the rest of the chapter.

Improving the Management

of Stress and Time

Managing stress and time is one of the most crucial, yet

neglected, management skills in a competent manager’s

repertoire. Here is why: The National Institute for

Occupational Safety and the American Psychological

Association estimate that the growing problem of stress

on the job siphons off more than $500 billion from the

nation’s economy. Almost half of all adults suffer adverse

health effects due to stress; the percentage of workers

feeling “highly stressed” more than doubled from 1985

to 1990 and doubled again in the 1990s. In one survey,

37 percent of workers reported that their stress level at

work increased last year, while less than 10 percent say

their stress level decreased. Between 75 and 90 percent

of all visits to primary care physicians are for stress-

related complaints or disorders. An estimated one

million workers are absent on an average working day

because of stress-related complaints, and approximately

550,000,000 workdays are lost each year due to stress.

In one major corporation, more than 60 percent of

absences were found to be stress related, and in the

United States as a whole, about 40 percent of worker

turnover is due to job stress. Between 60 and 80 percent

of industrial accidents are attributable to stress, and

worker compensation claims have skyrocketed in the

last two decades, with more than 90 percent of the law-

suits successful. It is estimated that businesses in the

United States alone will spend more than $12 billion on

stress management training and products this year

(American Institute of Stress, 2000). Name any other

single factor that has such a devastating and costly effect

on workers, managers, and organizations.

A review of the chapters in a recent medical book

on stress illustrates the wide-ranging and devastating

effects of stress: stress and the cardiovascular system,

stress and the respiratory system, stress and the endo-

crine system, stress and the gastrointestinal tract,

stress and the female reproductive system, stress and

reproductive hormones, stress and male reproductive

functioning, stress and immunodepression, stress and

neurological disorders, stress and addiction, stress

and malignancy, stress and immune functions with

HIV-1, stress and dental pathology, stress and pain, and

stress and anxiety disorders (Hubbard & Workman,

1998). Almost no part of life or health is immune from

the effects of stress.

As an illustration of the debilitating effects of job-

related stress, consider the following story reported by

the Associated Press.

Baltimore (AP) The job was getting to the

ambulance attendant. He felt disturbed by the

recurring tragedy, isolated by the long shifts.

His marriage was in trouble. He was drinking

too much.

One night it all blew up.

He rode in back that night. His partner

drove. Their first call was for a man whose leg

had been cut off by a train. His screaming and

agony were horrifying, but the second call was

worse. It was a child-beating. As the attendant

treated the youngster’s bruised body and

snapped bones, he thought of his own child.

His fury grew.

Immediately after leaving the child at the

hospital, the attendants were sent out to help a

heart attack victim seen lying in a street. When

they arrived, however, they found not a cardiac

patient but a drunk—a wino passed out. As they

lifted the man into the ambulance, their frustra-

tion and anger came to a head. They decided to

give the wino a ride he would remember.

The ambulance vaulted over railroad

tracks at high speed. The driver took the cor-

ners as fast as he could, flinging the wino

from side to side in the back. To the atten-

dants, it was a joke.

Suddenly, the wino began having a real

heart attack. The attendant in back leaned

over the wino and started shouting. “Die, you

sucker!” he yelled. “Die!”

He watched as the wino shuddered. He

watched as the wino died. By the time they

reached the hospital, they had their stories

straight. Dead on arrival, they said. Nothing

they could do.

The attendant, who must remain anony-

mous, talked about that night at a recent

counseling session on “professional burnout”—

a growing problem in high-stress jobs.

112

CHAPTER 2 MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS

SKILL

LEARNING

MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS CHAPTER 2 113

As this story graphically illustrates, stress can pro-

duce devastating effects. Personal consequences can

range from inability to concentrate, anxiety, and depres-

sion to stomach disorders, low resistance to illness, and

heart disease. For organizations, consequences range

from absenteeism and job dissatisfaction to high accident

and turnover rates.

THE ROLE OF MANAGEMENT

Amazingly, a 25-year study of employee surveys

revealed that incompetent management is the largest

cause of workplace stress! Three out of four surveys

listed employee relationships with immediate supervi-

sors as the worst aspect of the job. Moreover, research in

psychology has found that stress not only affects work-

ers negatively, but it also produces less visible (though

equally detrimental) consequences for managers them-

selves (Auerbach, 1998; Staw, Sandelands, & Dutton,

1981; Weick, 1993b). For example, when managers

experience stress, they tend to:

❏ Selectively perceive information and see only

that which confirms their previous biases

❏ Become very intolerant of ambiguity and

demanding of right answers

❏ Fixate on a single approach to a problem

❏ Overestimate how fast time is passing (hence,

they often feel rushed)

❏ Adopt a short-term perspective or crisis mentality

and cease to consider long-term implications

❏ Have less ability to make fine distinctions in

problems, so that complexity and nuances are

missed

❏ Consult and listen to others less

❏ Rely on old habits to cope with current situations

❏ Have less ability to generate creative thoughts

and unique solutions to problems

Thus, not only do the results of stress negatively

affect employees in the workplace, but they also drasti-

cally impede effective management behaviors such as

listening, making good decisions, solving problems effec-

tively, planning, and generating new ideas. Developing

the skill of managing stress, therefore, can have signifi-

cant payoffs. The ability to deal appropriately with stress

not only enhances individual self-development but can

also have an enormous bottom-line impact on entire

organizations.

Unfortunately, most of the scientific literature on

stress focuses on its consequences. Too little examines

how to cope effectively with stress, and even less

addresses how to prevent stress (Hepburn, McLoughlin,

& Barling, 1997). We begin our discussion by present-

ing a framework for understanding stress and learning

how to cope with it. This model explains the major

types of stressors faced by managers, the primary reac-

tions to stress, and the reasons some people experi-

ence more negative reactions than others do. The last

section presents principles for managing and adapting

to stress, along with specific examples and behavioral

guidelines.

Major Elements of Stress

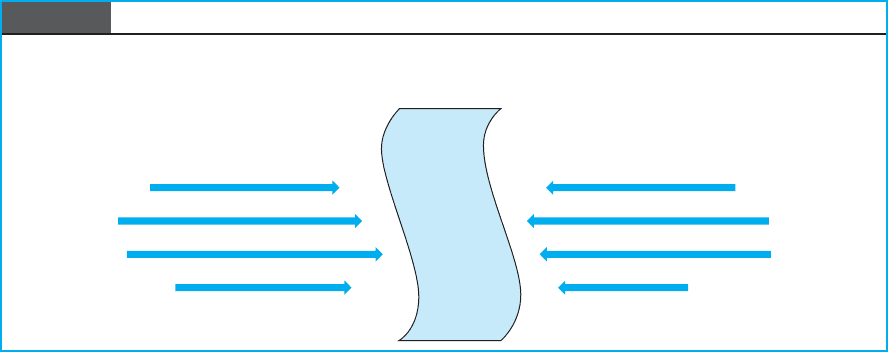

One way to understand the dynamics of stress is to

think of it as the product of a “force field” (Lewin,

1951). Kurt Lewin suggested that all individuals and

organizations exist in an environment filled with rein-

forcing or opposing forces (i.e., stresses). These forces

act to stimulate or inhibit the performance desired by

the individual. As illustrated in Figure 2.1, a person’s

level of performance in an organization results from fac-

tors that may either complement or contradict one

another. Certain forces drive or motivate changes in

behavior, while other forces restrain or block those

changes.

According to Lewin’s theory, the forces affecting

individuals are normally balanced in the force field. The

strength of the driving forces is exactly matched by

the strength of the restraining forces. (In the figure,

longer arrows indicate stronger forces.) Performance

changes when the forces become imbalanced. That is, if

the driving forces become stronger than the restraining

forces, or more numerous or enduring, change occurs.

Conversely, if restraining forces become stronger or

more numerous than driving forces, change occurs in

the opposite direction.

Feelings of stress are a product of certain stressors

inside or outside the individual. These stressors can be

thought of as driving forces in the model. That is, they

exert pressure on the individual to change present levels

of performance physiologically, psychologically, and

interpersonally. Unrestrained, those forces can lead to

pathological results (e.g., anxiety, heart disease, and

mental breakdown). However, most people have devel-

oped a certain amount of resiliency or restraining forces

to counter stressors and inhibit pathological results.

These restraining forces include behavior patterns, psy-

chological characteristics, and supportive social relation-

ships. Strong restraining forces lead to low heart rates,

good interpersonal relationships, emotional stability, and

114 CHAPTER 2 MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS

effective stress management. An absence of restraining

forces leads to the reverse.

Of course, stress produces positive as well as neg-

ative effects. In the absence of any stress, people feel

completely bored and lack any inclination to act. Even

when high levels of stress are experienced, equilibrium

can be restored quickly if there is sufficient resiliency.

In the case of the ambulance driver, for example, mul-

tiple stressors overpowered the available restraining

forces and burnout occurred. Before reaching such an

extreme state, however, individuals typically progress

through three stages of reactions: an alarm stage, a

resistance stage, and an exhaustion stage (Auerbach,

1998; Cooper, 1998; Selye, 1976).

REACTIONS TO STRESS

The alarm stage is characterized by acute increases in

anxiety or fear if the stressor is a threat, or by increases

in sorrow or depression if the stressor is a loss. A feeling

of shock or confusion may result if the stressor is partic-

ularly acute. Physiologically, the individual’s energy

resources are mobilized and heart rate, blood pressure,

and alertness increase. These reactions are largely self-

correcting if the stressor is of brief duration. However, if

it continues, the individual enters the resistance

stage, in which defense mechanisms predominate and

the body begins to store up excess energy.

Five types of defense mechanisms are typical of most

people who experience extended levels of stress. The first

is aggression, which involves attacking the stressor

directly. It may also involve attacking oneself, other

people, or even objects (e.g., whacking the computer). A

second is regression, which is the adoption of a behavior

pattern or response that was successful at some earlier

time (e.g., responding in childish ways). A third defense

mechanism, repression, involves denial of the stressor,

forgetting, or redefining the stressor (e.g., deciding that it

isn’t so scary after all). Withdrawal is a fourth defense

mechanism, and it may take both psychological and phys-

ical forms. Individuals may engage in fantasy, inattention,

or purposive forgetting, or they may actually escape from

the situation itself. A fifth defense mechanism is fixation,

which is persisting in a response regardless of its effective-

ness (e.g., repeatedly and rapidly redialing a telephone

number when it is busy).

If these defense mechanisms reduce a person’s

feeling of stress, negative effects such as high blood

pressure, anxiety, or mental disorders are never experi-

enced. The primary evidence that prolonged stress has

occurred may simply be an increase in psychological

defensiveness. However, when stress is so pronounced

as to overwhelm defenses or so enduring as to outlast

available energy for defensiveness, exhaustion may

result, producing pathological consequences.

While each reaction stage may be experienced as

temporarily uncomfortable, the exhaustion stage is the

most dangerous one. When stressors overpower or out-

last the resiliency capacities of individuals, or their ability

to defend against them, chronic stress is experienced and

negative personal and organizational consequences gen-

erally follow. Such pathological consequences may mani-

fest physiologically (e.g., heart disease), psychologically

(e.g., severe depression), or interpersonally (e.g., dissolu-

tion of relationships). These changes result from the

damage done to an individual for which there was no

defense (e.g., psychotic reactions among prisoners of

war), from an inability to defend continuously against a

stressor (e.g., becoming exhausted), from an overreac-

tion (e.g., an ulcer produced by excessive secretion of

Figure 2.1 Model of Force Field Analysis

Current Level of Functioning

Driving force A

Driving force B

Driving force C

Driving force D

Restraining force A

Restraining force B

Restraining force C

Restraining force D

MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS CHAPTER 2 115

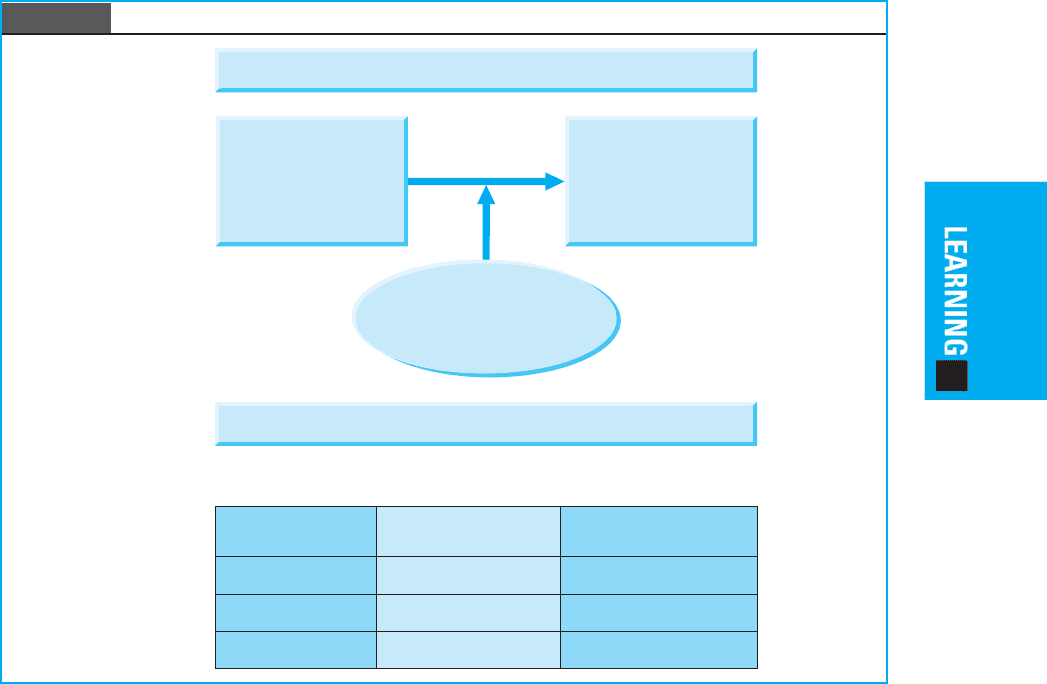

Figure 2.2 A General Model of Stress

body chemicals), or from lack of self-awareness so that

stress is completely unacknowledged.

Figure 2.2 identifies the major categories of stres-

sors (driving forces) that managers experience, as well

as the major attributes of resiliency (restraining forces)

that inhibit the negative effects of stress. Each of these

forces is discussed in some detail in this chapter, so

that it will become clear how to identify stressors, how

to eliminate them, how to develop more resiliency,

and how to cope with stress on a temporary basis.

COPING WITH STRESS

Individuals vary in the extent to which stressors lead to

pathologies and dysfunctions. Some people are labeled

“hot reactors,” meaning they have a predisposition to

experience extremely negative reactions to stress (Adler &

Hillhouse, 1996; Eliot & Breo, 1984). For others, stress is

experienced more favorably. Their physical condition,

personality characteristics, and social support mech-

anisms mediate the effects of stress and produce

resiliency, or the capacity to cope effectively with stress.

In effect, resiliency serves as a form of inoculation against

the effects of stress. It eliminates exhaustion. This helps

explain why some athletes do better in “the big game,”

while others do worse. Some managers appear to be bril-

liant strategists when the stakes are high; others fold

under the pressure.

An elaboration of the differences in dispositions

toward stress reactions comes from a set of studies in

which hot reactors were more likely to be women (men

reacted more quickly to stress, but more factors pro-

duced stress in women); individuals with low self-

esteem and who viewed themselves as less attractive;

and children who had been neglected, fearful, or in

chaotic or broken homes (Adler, 1999). Physician Frank

Trieber reported: “If you come from a family that’s

somehow chaotic, unstable, not cohesive, harboring

grudges, very early on, it’s associated later with greater

blood pressure reactivity to various types of stress.”

In managing stress, using a particular hierarchy of

approaches has been found to be most effective (Kahn &

Byosiere, 1992; Lehrer, 1996). First, the best way to

manage stress is to eliminate or minimize stressors with

EXPERIENCING STRESS

MANAGING STRESS

• Anticipatory

• Encounter

• Time

• Situational

• Physiological

• Psychological

• Physical

• Psychological

• Social

Enactive Strategies

Purpose

Eliminate

stressors

Permanent

Enactive

Long time

Develop resiliency

strategies

Long term

Proactive

Moderate time

Learn temporary

coping mechanisms

Short term

Reactive

Immediate

Effects

Approach

Time

Required

Proactive Strategies Reactive Strategies

Stressors Reactions

Resiliency

116 CHAPTER 2 MANAGING PERSONAL STRESS

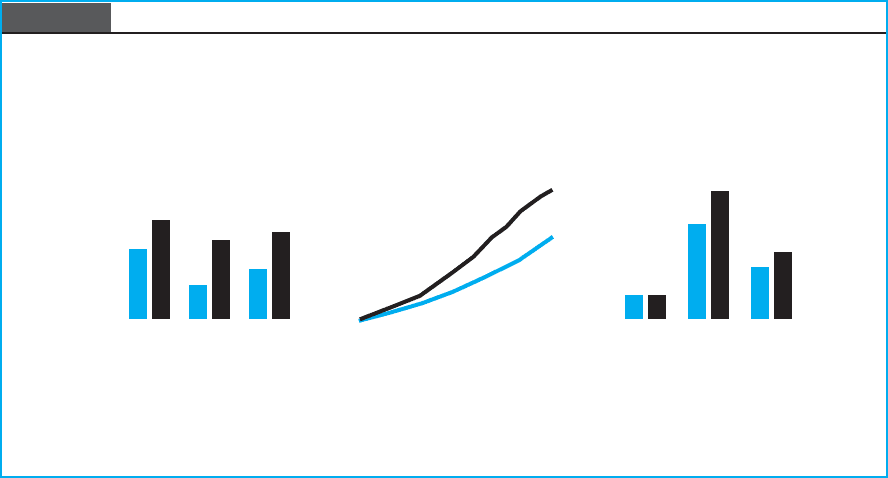

Figure 2.3 Some Physiological Effects of Stress

enactive strategies. These create, or enact, a new

environment for the individual that does not contain the

stressors. The second most effective approach is for indi-

viduals to enhance their overall capacity to handle stress

by increasing their personal resiliency. These are called

proactive strategies and are designed to initiate action

that resists the negative effects of stress. Finally, devel-

oping short-term techniques for coping with stressors is

necessary when an immediate response is required.

These are reactive strategies; they are applied as on-

the-spot remedies to reduce temporarily the effects of

stress.

To understand why this hierarchy of stress manage-

ment techniques is recommended, consider the physio-

logical processes that occur when stress is encountered.

Experiencing a stressor is like stepping on the accelera-

tor pedal of an automobile: the engine “revs up.” Within

seconds, the body prepares for exertion by having blood

pressure and heart rate rise substantially. The liver pours

out glucose and calls up fat reserves to be processed into

triglycerides for energy. The circulatory system diverts

blood from nonessential functions, such as digestion, to

the brain and muscles. The body’s intent is to extinguish

the stress by either “fight or flight.” However, if the

stressor is not eliminated as a result of these physiologi-

cal responses, the elevated blood pressure begins to take

its toll on arteries. Moreover, because the excess fat and

glucose don’t get metabolized right away, they stay in

the blood vessels. Heart disease, stroke, and diabetes are

common consequences. If the stress continues, minutes

later a second, less severe physiological response occurs.

The hypothalamus signals the pituitary to produce a

substance called ACTH. This substance stimulates the

adrenal cortex to produce a set of hormones known as

glucocorticoids. The action of ACTH serves to stimulate

a part of the brain vital to memory and learning, but

an excess actually can be toxic. That’s why impaired

memory and lower levels of cognition occur under con-

ditions of high stress. People actually get dumber! These

same glucocorticoids also suppress parts of the immune

system, so chronic stress leaves people more vulnerable

to infections. Figure 2.3 summarizes these physiological

consequences.

Individuals are better off if they can eliminate

harmful stressors and the potentially negative effects of

frequent, potent stress reactions. However, because

most individuals do not have complete control over

their environments or their circumstances, they can sel-

dom eliminate all harmful stressors. Their next-best

alternative, therefore, is to develop a greater capacity to

withstand the negative effects of stress and to mobilize

the energy generated by stressors. Developing personal

resiliency that helps the body return to normal levels of

activity more quickly—or that directs the “revved up

engine” in a productive direction—is the next best

strategy to eliminating the stressors altogether.

SOURCE: American Institute of Stress (2000), http://www.stress.org/problem.htm.

Immune Response

People who care for spouses

with dementia didn’t

respond to a flu vaccine as

well as a control group.

People with Full Response*

100

80

60

40

20

0

%

0–70 70+ ALL

Age in years

Caregiver

Control

Coronary Disease

Men who said they were

highly stressed were more

likely to have heart attacks

and strokes.

Heart-Disease Incidence

†

10

8

6

4

2

0

%

135791113

Years in study

High-

stress

group

Low-

stress

group

1 month

3 months

Viral Infection

The chances of catching a

cold increased the longer

people experience work or

interpersonal stress.

Relative Risk of a Cold

5

4

3

2

1

0

No

stress

Work Inter-

personal

*

Percent with a fourfold antibody resistance.

†

Cumulative annual incidence.

Sources: “Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults.”

“Self-perceived psychological stress and incidence of coronary artery disease in middle-aged men.”

“Types of stressors that increase susceptibility to the common cold in healthy adults.”