Water Power and Dam Construction - Issue May 2009

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

and the tensile strength ranges from less than 1-14MPa.

Host rock challenges for tunnelling activities include:

• High in-situ ‘locked in’ ho r i zontal stress three to five times the

vertical stress.

• Shale degradation when exposed to air.

• A groundwater regime including very permeable aquifers in the

upper units, highly corrosive groundwater below the DeCew for-

mation, a regional acquitard provided by the Rochester shale and

very low permeability but highly corrosive connate pore water in

the Queenston formation.

• Natural gases (methane) detected in various formations.

• Time-dependent deformations including squeezing into excava-

tions due to relief of high stresses. Swelling potential of the shale

u

nits is well documented in the Niagara region. It is believed to

be initiate d by the relief of the high in-situ stresses, sh ales that

‘swell’ i n fresh water or hum i d i t y and due to ionic diffusion of

salts from the connate pore water.

T

UNNEL DESIGN

The planned tunnel alignment sees the tunnel descend 1400m on a

7.82% decline from the outlet through the upper sedimentary layers

and into the Queenston shale formation to a depth of 140m below

the ground surface. From there, the tunnel was planned to follow a

relatively flat plane for about 7800m before rising towards the intake

on a 7.28% incline for the final 1200m. All horizontal and vertical

curves have a radius of 1000m and there are no compound curves.

The significant challenges of safely excavating and supporting the

Queenston shale have resulted in rerouting part of the tunnel, rising

to the underside of the Whirlpool sandstone formation, about 100m

below the ground surface, starting about 3300m along the tunnel

drive (see Figure 2). To facilitate the vertical realignment, the hori-

zontal alignment was shifted about 200m east, directly below Stanley

Avenue and out from the shadow of the existing SAB2 tunnels (see

Photo 1). This shortened the tunnel length by about 200m to 10.2km.

The clay minerals in the Queenston formation expand and absorb

water, resulting in rock swelling that could potentially put the tunnel

lining under a great deal of stress. The rock swelling was studied in

detail during the project’s definition phase. Strabag’s design features

TUNNELLING

T

HE PROJECT TEAM

Due to their expertise in tunnel design and construction, prior work

on the project and knowledge of the area, OPG engaged Hatch Mott

MacDonald (Mississauga) in association with Hatch Acres (Niagara

Falls) as the owner’s representative to assist with administration of

the design-build contract, to review design documentation and to

monitor construction.

Through an international proposal competition, OPG contracted

with Strabag to design and construc t the Niagara t unnel.

Headquartered in Vienna, Austria, Strabag has extensive interna-

tional tunnelling experience, having built many of Europe’s railway

and highway tunnels. Strabag’s project team includes ILF (Austria)

as tunnel engineer, Morrison Hershfield (Toronto) as surface works

engineer, Isherwood (Mississauga) as cofferdam engineer, and sev-

eral local specialty subcontractors including Dufferin Construction

(Oakville) for surface works and excavated materials handling,

Castonguay (Sudbury) for blasting, McNally and Bermingham

(Hamilton) for in-water works, Geofoundations (Acton) for grout-

ing, Dufferin Concrete (Toronto) for shotcrete and concrete supply,

and Jegel (Toronto) for quality control.

G

EOLOGICAL SETTING AND CHALLENGES

The Niagara regi on is underlain by Cambrian, Ordovician and

Silurian sedimentary rocks having a total thickness of approximately

800-900m (see Figure 1). The formations feature near horizontal

bedding that dips at 2m/km from east to west. The strata include

dolostones, dolomitic limestones, sandstones, and shales.

The Niagara river gorge was formed by erosion during the last

major ice retreat, about 12,000 years ago. Then, the Niagara river

ran through the St. Davids gorge, but roughly 10,000 years ago its

route changed to the current alignment. The falls eroded and retreat-

ed at a rate of approximately 1m per year to where they are today,

with retreat now slowed by counter measures and the diversion of

about two-thirds of the flow for power generation.

Geotechnical investigations were carried out in stages and includ-

ed 58 boreholes, in-situ stress measurements, groundwater moni-

toring wells and an exploratory adit. Concept phase investigations

for pot ential development schemes were carried out by Ontario

Hydro from 1983-89. Definition engineering studies were carried

out from 1990-93. Investigations in 1992-3 included the excavation

of an adit with a 12m diameter trial enlargement in the Queenston

formation about 1km from the tunnel outlet.

In the various formations above the Queenston shale mudstone,

the unconfined compressive strength ranges from 12-242MPa while

the tensile strength ranges from 6-9MPa. In the Queenston forma-

tion, the unconfined compressive strength ranges from 7-120MPa

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM MAY 2009 21

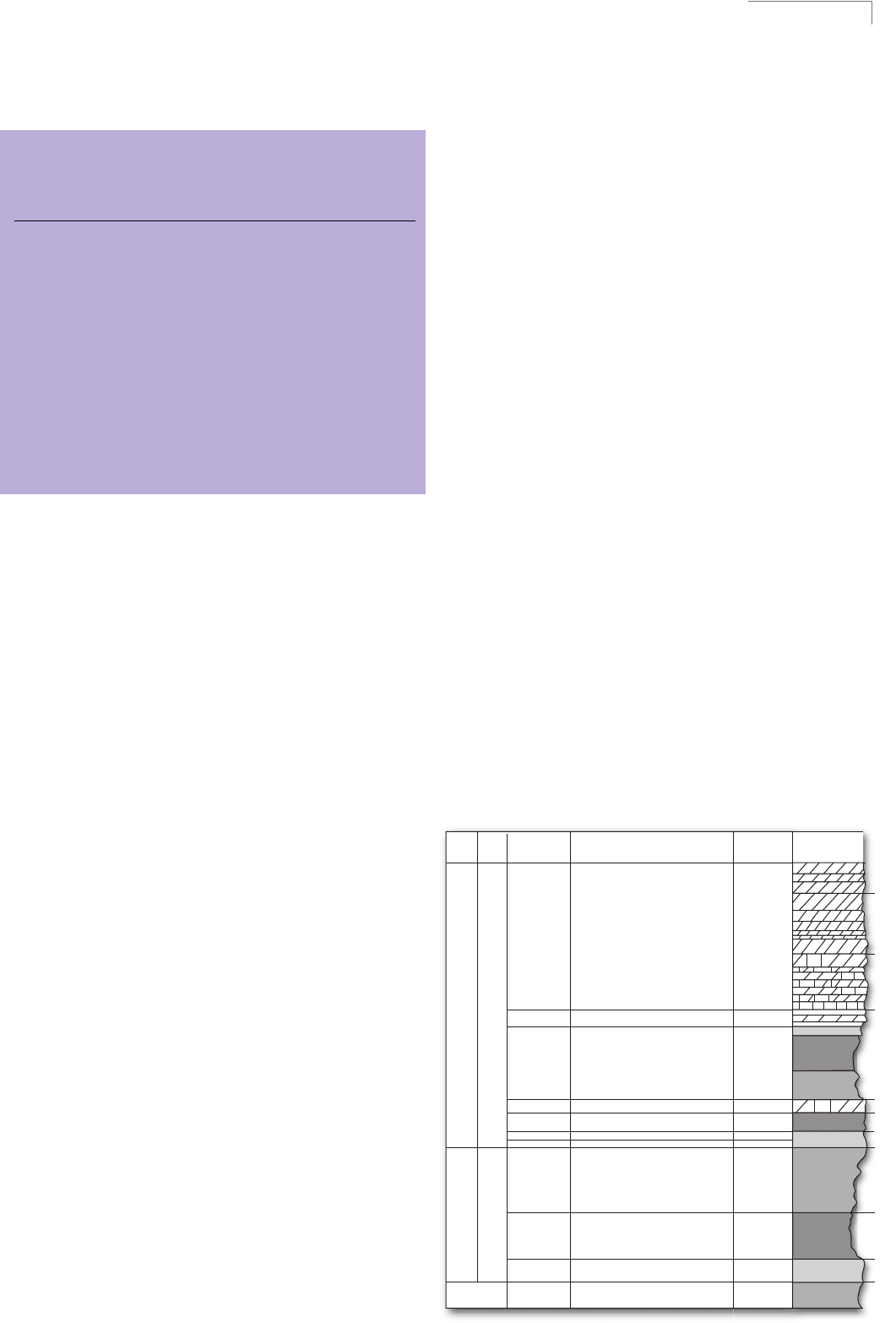

Niagara river hydro facilities

Facility In-service Diversion Station Annual Annual

y

ear capacity capacity energy capacity

m

3

/sec MW TWh factor

Sir Adam Beck No.1 1922 600 498 2.6

Sir Adam Beck No.2 1954 1,200 1,499 9.2

Sir Adam Beck PGS 1958 - 174 (0.1)

Current Totals 1,800 2,171 11.8 0.63

Niagara Tunnel n/a 500 - 1.6

Totals (Canada) 2,300 2,171 13.4 0.72

R

obert Moses 1964 3,000 2,400 14.2

Lewiston PGS 1964 - 300 (0.5)

Totals (USA) 3,000 2,700 13.7 0.60

Age

Ordov-

ician

Formation Symbol

Lockport

Reynales

Neahga

Irondequoit

Grey to reddish dolomitic limestone

Thorold

Green shale

White sandstone

1.8

2.4

Grey crystalline dolomitic

Limestone

Dark grey calcareous shale

dolomite interbedded

Green, irregularly bedded

sandstone with red shale

interbeds

Grey shale to white

calcareous sandstone

Light grey crossbedded

sandstone

Red shale and

argillaceous limestone

Light grey crystalline dolomite

16.8

–

20.3

17.7

3.6

16

11.5

335

3.6 –

7.6

2.1– 4.0

1.2– 3.1

Crystalline dolomite & grey mudstone

Decew

Rochester

Grimsby

Power

Glen

Whirlpool

Queenston

Brief description

Approx.

Thickness

(m)

Group

AlbermarleClintonCataract

Middle SilurianLower Silurian

Figure 1 – Project Geology

22 MAY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

TUNNELLING

a two-pass approach developed to ensure the tu nnel is protected

from swelling rock.

As the tunnel is being bored, workers behind the TBM cutterhead

install various combinations of steel ribs, wire mesh, and rock bolts

to reinforce the rock. The surrounding surface is then sprayed with

a layer of shotcrete to cover the exposed rock and form a protective

shell. The tunnel is su bsequently lined with a polyolefin water-

proofing membrane that prevents fresh water in the tunnel from

entering the host rock and eliminates the swelling potential. The final

liner consists of cast-in-place concrete 600mm thick.

The tunnel is being driven by a Robbin s (Solon, Ohio, US) full

face, open gripper TBM with an outside diameter of 14.44m. It is

the largest in the world of this type. The tunnel design inside diam-

eter varies between 12.4- 13m depending on t he primary su pport

class dictated by the host rock conditions.

The smaller diameter reflects the less frequ ently ex pected c ase

where steel ribs and mesh would be required with up to 100mm of

25MPa shotcrete. The other primary support classes vary from mesh

with 50mm of shotcrete, to steel channels with mesh and rockbolts

up to 6m in length, and 80mm of 25MPa shotcrete.

The final lining incorpor ates a polyolefin waterproofing mem -

brane to prevent swelling of the host rock, a 120 degree cast-in-situ

concrete inv ert, a 240 degree cast-in-situ concrete arch, contact

grouting to fill voids and interface grouting to pre-stress the liner

against the internal pressure during operation. The waterproof mem-

brane is installed between the shotcrete sprayed onto the exposed

rock surface and the final concrete lining. It is essential to the design

life and quality of the tunnel lining because it prevents fresh water

flowing through the tunnel from leaking into the surrounding rock

and displacing the supersaturated salt water trapped in the rock. If

this were to occur, the rock around the tunnel, in p articular the

Queenston shale, would swell and over-stress the concrete lining.

Use of this type of waterproof membrane is rare in North

America, but it is used in many railway and highway tunnels in

Europe. An added benefit of the membrane is that the concrete used

to build the final liner can be thinner and does not require reinforc-

ing steel. The concrete lining thickness has been optimised based on

structural requirements and placement constraints.

C

ONSTRUCTING THE TUNNEL

The tunnel excavation is being done by the ‘Big Becky’ TBM and her

supporting cast of construction workers. Measuring 150m long, more

than four storeys tall and weighing about 4000 metric tonnes, Big

Becky was named through a contest involving students from across

the Niagara region. The winning submission came from children at

Port Weller Public School in St. Catharines, Ontario. The children

say they chose the name in honor of Sir Adam Beck, the man who

presided over the building of the original SAB1 generating station.

Big Becky was designed, manufactured and built in less than 12

months. She was assembled in the 300m long, 23m wide, 30m deep

rock cut outlet canal using custom p arts shipped from Germany,

Hungary, Italy, Slovenia, the UK, the US and Canada (see Photo 2).

Big Becky is digging under the City of Niagara Falls from the Sir

Adam Beck generating complex, near Queenston, to the interna-

tional Niagara control works located about 1.5km upstream from

the Hors eshoe Fall s. The control w orks extends about half way

across the Niagara river to regulate the flow of water over the falls

in accordance with the 1950 Treaty and also facilitates ice manage-

ment in the vicinity of the hydro power diversion intakes.

Big Becky’s cutterhead is dressed with 85 x 508mm cutters and is

powered by 15 x 315kW variable frequency electric motors to carve

through the 450M-year-old rock that underlies Niagara Falls. Big

Becky progresses through the tunnel by first using hydraulic pistons

to push heavy steel gripper pads against the tunnel sides for support.

The cutterhead, rotating at up to 5rpm, then bores through about

1.8m of solid rock as hydraulic thrust cylinders push the cutterhead

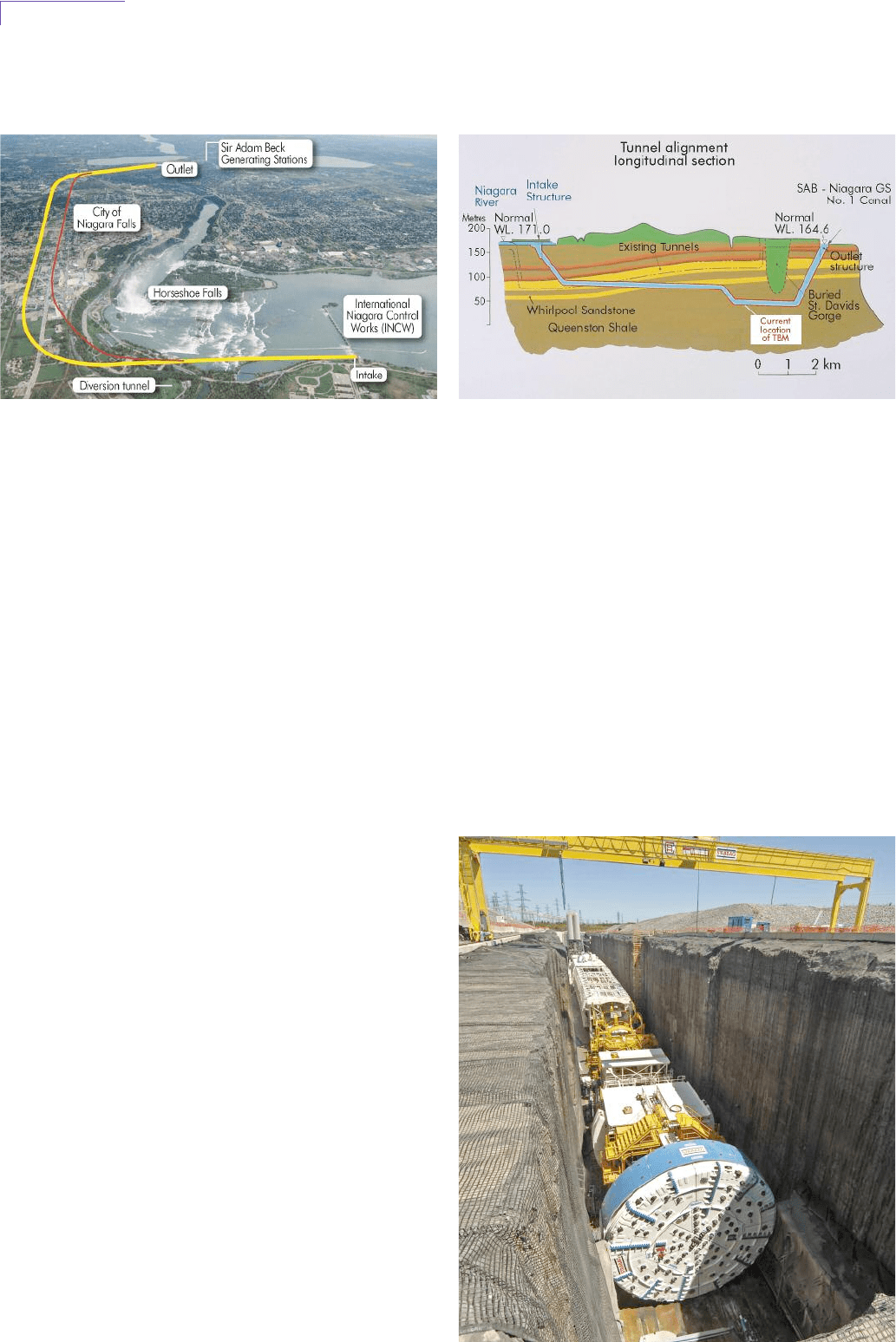

Left: Photo 1 – The yellow line is the planned route for the Niagara tunnel and the red line shows the horizontal re-routing east of the existing SAB2 tunnels to

facilitate a higher alignment for the tunnel south of the buried St.Davids gorge; Right: Figure 2 – Realigned Niagara tunnel profile

Photo 2 – To create a place for the 4000t tunnel boring machine known as

Big Becky to begin boring, a rectangular pit measuring 300m long, 23m wide,

and 40m deep was excavated. Big Becky began boring under the City of

Niagara Falls, Ontario, in September 2006

ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE

Necessary depression

T

urbines require depression

in their bearings. In order to

create this depression there

can be used blowers which,

depending upon the size of

a turbine, extract the

volume of air necessary to

achieve depression.

At the same time oil

mist is also withdrawn by suction. In order to prevent the emerging

carbons from entering into the proximity of a turbine or directly into

the atmosphere, filter systems are used.

Different filter systems fulfil this purpose. Both centrifugal sepa-

rators and electrostatic filters can be used. The significant differ-

ence though, is the efficiency level and quality of the filtered oil.

Filters working on mechanical basis allow to achieve the highest

possible efficiency.

The coalescence effect

The most effective method is the filtration according to the coales-

cence effect.

In this way oil par ticles are separated drop by drop and are led

continuously via the

drain line back into

the lube oil tank. An

important aspect is that

the original quality of oil

remains constant.This significantly extends lifetime of oil which has

a positive impact on the mechanical parts of the system.

Advantages at first sight

1. complete separation of oil mist

2. adjustable vacuum for every bearing

3. low differential pressure of filter elements

4. regeneration of the filter elements

5. recovery of expensive oil

6. minimization of risk of accidents and fire hazards

7. reduction of maintenance costs

This filtration method is app licable at nearly all gas and stea m

turbines, gas and diesel m otors, hydro turbines, compressors

and generators .

Separating visible oil mist by

means of the coalescence effect

Creation of necessary depression and extraction

of finest oil mist particles

24 MAY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

TUNNELLING

forward. The grippers are retracted after the rear legs are lowered

for support, and the backup trailers are pulled forward with anoth-

er set of hydraulic cylinders to catch up with the front of the TBM

in a caterpillar-like motion.

Concurrently, the trailing series of 1600t/hr conveyor belts carry

the excavated rock out of the tunnel to a storage area located on OPG

property at the Sir Adam Beck generating complex. The excavated

Queenston shale will become feedstock for Ontario’s clay brick indus-

try, while excavated limestones from the intake and outlet excavations

were recovered for on-site uses and nearby public works projects.

Big Becky began her underground journey in September 2006. It

will take several years to complete the tunnel drive. By the time Big

Becky arrives at the tunnel inta ke, she will have bored through

1

.7Mm

3

o

f solid rock.

Compared to the 10,000 workers needed to build SAB1, the new

Niagara tunnel is being constructed with an average of only 230 work-

ers, rising to about 350 workers during periods of peak activity. This

unionised job site features a predominately Canadian workforce work-

ing on a 24/7 cycle with two production shifts at 10 hours each, plus

one maintenance shift. Despite the challenging conditions and on-site

effort to date exceeding 2.2M hours, the crews and site management

team have achieved a commendable lost time injury frequency rate

below 1.0 per 200,000 hours worked, which compares favourably to

the Ontario heavy civil construction industry rate of 2.9.

One of the challenges faced by the site team is the running of ser-

vices and logistics through the various work platforms as the place-

ment of the cast-in-place concrete liner is carried out concurrent with

TBM excavation. Up to four concurrent activities could be staged

along the tunnel route before hole-through of the TBM.

L

INING STATION

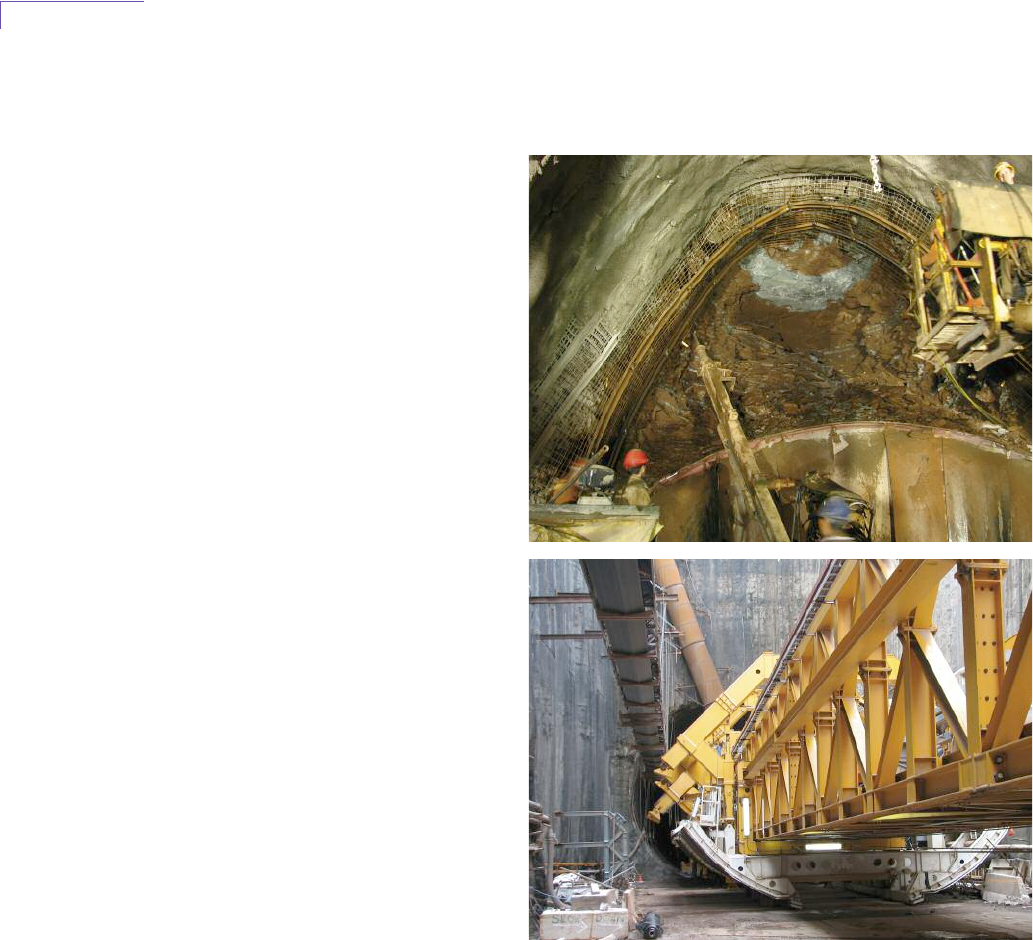

Launched in December 2008, and trailing behind the TBM by about

3000m, is the 800t invert lining work station (see Photo 3). It was

engineered and fabricated by Strabag group companies BMTI and

Baystag. An 87m long bridge section, ramped at both ends, allows

the rubber tired tunnel supply vehicles to travel uninterrupted in a

single lane as the polyolefin membrane is installed and the in vert

concrete is cast. The crown and sidewall bracings on the invert form-

work, necessary to prevent heave, have been designed so as not to

interfere with the 2.6 m diameter fresh air supply duc t. This runs

along the tunne l crown or the sidewall mounted conveyor a nd

opposing electrical, communication and water services. The invert

is being cast using two 12.5m long forms that can be leapfrogged to

facilitate 25m of invert lining advance per day.

Excessive overbreak in the tunnel crown, p articularly in the

Queenston shale formation (see Photo 4), has necessitated addition

of the 100t infill carrier to restore the profile prior to installing the

membrane and arch concrete. It will follow the invert lining by about

1500m and is currently planned for launch in September 2009. It

will provide elevated work platforms to accommodate drill jumbos,

grouting facilities, shotcrete robots and material handling equipment

needed for the arch profile restoration.

Trailing the infill carrier by another 1500m will be the twin 12.5m

arch forms and associated membrane installation platform config-

ured like the invert lining work station to facilitate daily advance of

up to 25m. The arch installation carrier weighs in at a hefty 1800t

and totals about 450m in length. The heavyweight steel is required

in t he design to resist the concrete loads. The membrane wi ll be

installed using Velcro to hold it in place and all seams will be heat

welded and fully tested. Tubes with ports for pressure grouting will

be installed every 3m along the tunnel lining to facilitate the subse-

quent grouting operations. The arch lining train will carry services

and ventilat io n , together with the conveyor, on fastene r s that are

part of its superstructure to channel them through the work area as

the membrane and arch concrete are placed.

A further 2000m behind the arch concrete operation will be the

60t contact grouting station. The 60t pre-stress grouting work plat-

form will follow by another 1 5 0 0m to complete the tunne l ’s per-

manent lining.

Ventilation is presently by means of two 355kW fans for an air

supply to the TBM of 75m

3

/sec. A 75kW secondary fan is installed

on the TBM back-up. Once the arch lining is underway, a further

75m

3

/sec will be delivered to the shutter area to dissipate heat gen-

erated during the curing process.

To supply shotcrete and concrete to the tunnel, a batch plant was

built just outside the tunnel’s entrance along with a water treatment

plant that is used to clarify water pumped from the tunnel before it

is discharged to the nearby hydro canal.

I

NTAKE WORKS

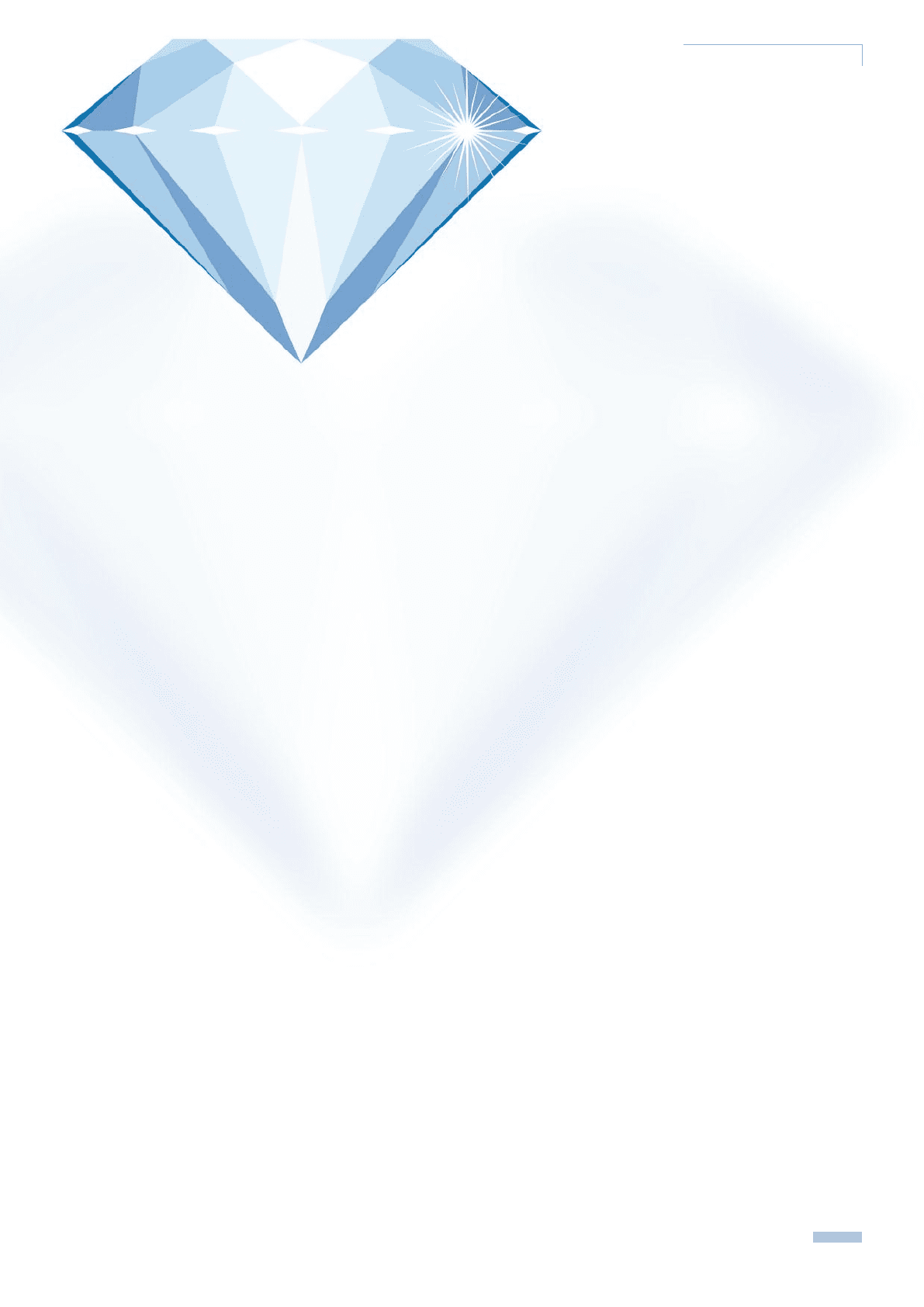

Overshadowed by the presence of Big Becky, work at the currently

separate intake site is an impressi ve project in its own ri ght ( see

Photos 5 an 6). Located at the gates of the International Niagara

Control Works, in-water blasting was used and precast concrete bins

were stacked, backfill ed and capped to form the replacement

ice-management Accelerating Wall and shoreline retaining wall. A

sheet pile cellular cofferdam has been constructed in the river and

was dewatered in July 2007. Blasting and rock excavation of the

approach channel then got underway, together with grouting works

to seal the two main sources of inflow, leaks through the cofferdam

and through horizontal layering in the riverbed. The impressive

Above, top: Photo 3 – Excessive crown overbreak in the Queenston shale

formation requires addition of an overbreak infill operation to restore the

tunnel profile before placement of the polyolefin membrane and arch concrete;

Above: Photo 4 – Launching the invert concrete work platform in December

2008. Rubber-tyred trucks delivering materials supporting the TBM advance

drive over the bridge while the membrane and concrete are placed below

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM MAY 2009 25

TUNNELLING

portal profile was achieved by controlled blasting, with scaling / pro-

filing by excavator mounted roadheader.

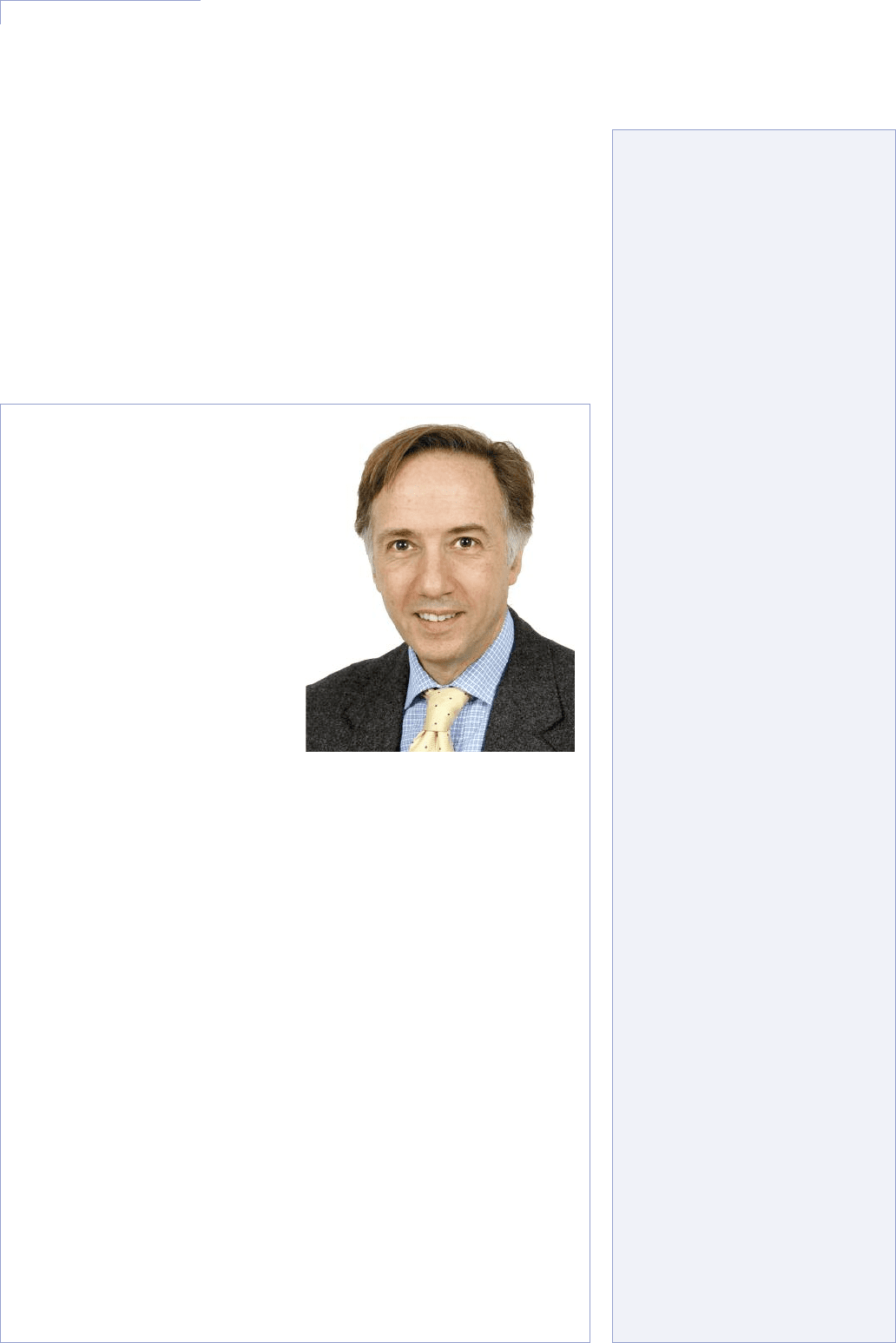

The 400m long, 8m wide and 7m high grout tunnel, now under

construction below the Niagara River bed (see Photo 7), is to pre-

condition and seal the ground in preparation for the TBM break-

through and to facilitate the demobilisation of the TBM once the

main tunnel drive is complete. Extensive grouting is being carried

out as the tunnel advances to prepare the ground so that the TBM

can drive along the grout tunnel alignment, without experiencing

problematic inflows, with the top of the TBM cutterhead just below

the crown of the grout tunnel.

C

URRENT STATUS

Excavating from the outlet, with the TBM launched in September

2006, the tunnel has been driven downward at a 7.82% grade that

has taken the tunnel through ten lay ers of shale, limestone and

dolomite. After breaking through the Whirlpool sandstone, a hard

abrasive rock, Big Becky encountered the much weaker Queenston

formation. Progress t hrough the contact zone between these two

rock formations was difficult, and significant modifications to the

initial support area, immediately behind the TBM cutterhead, were

completed to enhance the installation of initial roc k supp ort and

worker safety, a top priority on the project.

In the Queenston shale immediately below the Whirlpool sand-

stone contact and under the buried St. Davids gorge, Strabag installed

a series of 9m long horizontal pipe spile umbrellas to pre-support the

rock in the tunnel crown over Big Becky’s cutterhead. This tem-

porarily slowed the progress of the TBM to less than 3m per day. As

rock conditions improved, the spile umbrellas were discontinued and

the TBM advance rate increased. Crown overbreak in the Queenston

shale formation, up to 4m, and averaging about 1.5m, has been expe-

rienced with crews now averaging about 7m per day of TBM advance

under such conditions.

By mid-April 2009, the TBM had advanced over 3900m and the

invert concre te liner installation has advanced about 200m. The

progress of the tunnel boring machine has been slower than expect-

ed and considerable uncertainty remains with respect to the sched-

ule until the tunnel boring machine establishes more consistent

performance following the revised alignment.

Negotiations are currently in progress to re-establish the comple-

tion schedule and contract cost consistent with the recommenda-

tions of the Dispute Review Board concerning alleged differing sub-

surface conditions in the Queenston shale formation. As well as with

associated excessive crown overbreak, due to challenges experienced

excavating and supporting the apparently overstressed Queenston

shale in the tunnel crown. The ongoing negotiations are also includ-

ing contract changes associated with re-routing of the tunnel into

the more competent rock formations overlying the Queenston shale.

After Big Becky finishes her job, it will take another two years to

complete the installation of the permanent concrete lining and the

permanent structures required at the tunnel intake and outlet. The

new tunnel is expected to operate for at least 90 years without any

interruptions for maintenance.

Richard Everdell is the project director of the

Niagara tunnel project. He may be contacted at

Ontario Power Generation, 700 University Ave, H18,

Toronto, Ontario M5G 1X6 Canada

E-mail: rick.everdell@opg.com

IWP& DC

Above: Figure 3 – Niagara Tunnel Lining System

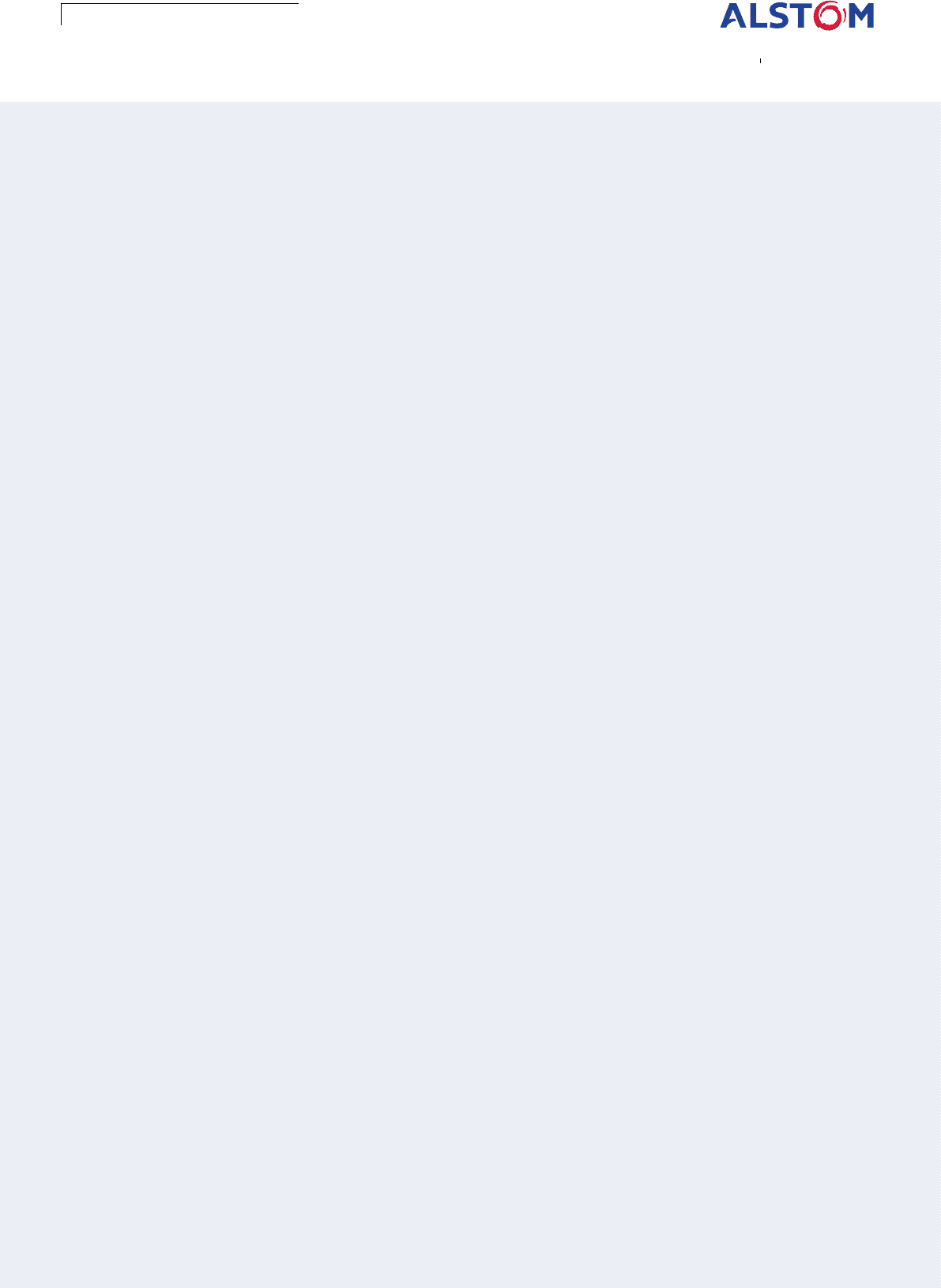

Right, top: Photo 5 – Niagara tunnel intake construction activity underway at

the inter national Niagara control works located about 1.5km from the

Horseshoe Falls; Middle: Photo 6 – Hydraulic model studies optimised the

intake channel excavation under construction to minimise entrance head

losses, avoid air entrainment and enhance ice passage; Bottom: Photo 7 –

The 400m long, 8m wide and 7m high drill and blast intake grout tunnel below

the Niagara river bed will minimise groundwater inflow before Big Becky

arrives to complete the tunnel dig

ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE

AN OVERVIEW OF MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS

IN THE LAST CENTURY.

The development of hydropower generation

It wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s that hydropower technology

started to expand rapidly. Closely linked to the economic boom in

Europe and North America after World War ll, the number of

hydropower projects in these regions, averaging between 12 and

15 GW per year marked a clear rise in hydropower generation. At

the time several countries created the basis for what represents

the face of today’s hydropower generation markets, i.e. 44% in

Sweden, 60% in Canada and as much as 98% in Norway.

The economic emergence of developing countries such as

Brazil in the 1980s increased the need for energy production,

pushing decision makers to consider using their enormous

natural resources – water – to answer the growing need for

electricity. This marked the construction of the first very big

power plant installations in South America. During these years,

the peak of wor ldwide installed hydropower capacity reached 23

GW per year. 25% of Brazil’s energy supply is produced at the

Itaipu power plant on the Paranà river, which is the world’s

second largest dam, with an overall production capacity of 14

GW. The first generator for this plant was installed in 1984, and

Alstom Hydro supplied 10 of the 20 x 750 MW Francis

turbine/generator units. This dam is classified as one of the

Seven Wonders of the World by the American Society of Civil

Engineers. Heavily involved in hydropower development in South

America, Alstom Hydro decided to invest in an 81,000 m²

manufacturing plant in Taubaté, Brazil, that has since gained a

strong reputation for its world-class hydro manufacturing quality

standards. Today, Brazil’s energy production heavily relies on

hydropower generation with over 85% of the country’s power

coming from this source. The tendency for the future is also for

strong growth, with new power plants in Rio Madeira and Santo

Antonio for which Alstom Hydro will supply 10 x 75 MW Bulb

turbines and 17 generators and 19 x 72 MW Bulb Turbines and

22 generators respectively.

With the growing demand for energy due to the high level of

industrialisation in Asia, particularly in China and India at the

beginning of the 21st century, the number of hydropower

installations increased even further to an unprecedented 40 GW

per year reaching a peak of 50 GW last year. Today’s largest

hydropower plant is situated on the Three Gorges dam on the

Yangtze River in China, providing a potential production capacity of

22,500 MW when completed in 2011. Alstom Hydro supplied 14

x 710 MW Francis turbine/generator units for this project.

representing 44%. of the total number of units. Understanding the

need to be closer to its customers in these emerging markets,

Alstom Hydro opened a manufacturing facility in Tianjin, China,

capable of producing turbine and generator units with capacities

up to 1,000 MVA, and both a manufacturing plant and a Global

Technology Centre in Baroda, India. These facilities enable Alstom

Hydro to maintain its high levels of R&D and manufacturing

standards while meeting growing market demand from Asia and

elsewhere around the world.

New challenges in an ever changing environment

One of today’s challenges in hydropower is the growing

importance of retrofit services for power plants that were built

during the economic boom in the 1960s and 1970s in Europe

and the US . Over the years, the efficiency levels of these ageing

power plants decreased to levels much lower than those of newer

plants. This is an important problem for utility owners who

experience a loss in production and profitability due to outages

and the reduced efficiency of plant equipment. Alstom Hydro

offers a solution to this problem through individually tailored

service packages, which incorporate three specific modules

(Assess, Secure & Extend, Reset & Upgrade) for all types of

hydroelectric power plants. One part of the Secure & Extend

module covers the area of upgrading in order to restore the

lifetime of existing equipment, increasing its performance levels

and reducing overall downtime. One example of a plant where

this has been applied is the Shasta power plant in the US whose

output during peak demand has been increased by approximately

30% thanks to Alstom Hydro’s retrofit programme.

Since the beginning of 2000, hydropower technology as a

renewable energy source, is taking centrepiece in the field of

environmental considerations, especially in Europe and in China.

Hydropower is a predictable environmentally friendly source of

energy that is widely used to regulate energy needs on the

network. Unlike wind farms that are subject to the unpredictable

changes of climate conditions the output of hydropower plants,

especially pumped storage hydropower plants, can be regulated to

meet electricity demands in real time. Alstom Hydro has

developed a number of specific technologies in reply to changing

market needs including hydrostatic water guide bearings

eliminating the risk of oil pollution in water, fish-friendly turbines

that allow fish to migrate up stream without being injured etc.

Moreover, Alstom Hydro continues to invest in R&D in order to

continuously introduce innovative technologies to the market.

R&D is key for existing plants as well as for new installations. It

ensures the highest possible efficiency of a power plant through

the design of turbines and generators made to match the needs of

each specific project – be it run-of-river, small hydro, large hydro or

retrofit – through individual studies, design and testing using its

eight test rigs located in the Alstom Hydro Global Technology

Centres in Grenoble, France, and in Baroda, India. These facilities

enable Alstom Hydro to better respond to local needs, in Asia,

Africa, Europe or the Americas, making it possible to provide

solutions for hydropower generation for more than 100 years to come.

100 years experience

in Hydropower

With over 100 years experience in designing and supplying equipment

for hydropower plants, Alstom Hydro is the number 1 leader in hydropower,

having supplied 400 GW in turbines and generators worldwide to date,

representing 25% of the global installed base.

S

INCE the dawn of history the labours

of mankind have been eased by water

power. It is the oldest source of

mechanical energy in the world: pro-

gressiv ely its abundant potential has been

harnessed…in the Nile, Euphrates and the

Yellow river…mountain torrent and tide.

After centuries of development the crude

wooden float wheel, which first lifted water

to a thirsty land, was transformed into the

majestic turbine o f today. Even in this

atomic age we appreciate, perha ps more

than ever before, the tru e importance of

water power; indeed there is plenty of evi-

dence to support the oft-expressed view that

the full development of hydroelectric

resources is an essential requir ement of

modern civilization.

These impressive first paragraphs are

actually the opening words of Volume one

of this esteemed journal. Launched in early

1949, Water Power – as it was known in

those days – was devel oped as a te chnical

journal devoted to the study of all aspects of

hydroelectric developments. Today, the jour-

nal has grown to include details of dam con-

struction – includ ing dams built for other

purposes than power generation – with an

accompanying sister title, Dam Engineering,

launched to deal with peer reviewed techni-

cal papers in this arena.

It is interesting to look back on the early

issues of the journal and discover the ways

in which the industry has grown. In the edi-

tors open ing letter for ex ample, it states:

“All to frequently the ge neration of elec-

tricity is considered an end in itself. Water

power resources have been developed as and

where required, in some cases, without con-

sideration of the overall needs of the com-

munity for water, irrigation, navigation and

community rights; and moreover, they have

sometimes been planned wastefully, to oper-

ate as self-contained units without regard to

the possibility of helpful interconnec tion

with thermal systems.” Today’s hydro

industry is a different crea ture altogether.

Environmental and social impact assess-

ments a re regularly carr ied out – w ithout

them it is often very difficult to o btain

finance for schemes. For example, I recent-

ly spo ke to a representativ e of the Inter-

American Development Bank (interview on

p66) where it wa s made clear just how

important lasting environmental social and

economic benefits are to potential investors!

We’ve carried a number of different articles

over recent years that look at the develop-

ment of environmental impacts assessments,

and have conducted interviews with numer-

ous finance companies, government officials

and certification organisations that stress the

importance of considering such issues.

I was particularly struck by a note in the

editor’s column which stated: “There is still

a broader outlook which considers the use

of water in regard to all aspects of man’s

needs – not only the power for his industry,

but the vital sustena nce for his agricul-

ture...Therefore we look forward to a time

when power commissions will produce large

scale overall plants; that such a vision c an

come true is shown by the example of the

Tennessee Valley Authority, and by schemes

which, if not yet in practical form, are being

considered by the Government’s of India and

Egypt.” There is little doubt that today that

vision is a reality. Multi-purpose dam pro-

jects are preva lent through out t he world,

and it’s not just for power generation and

agriculture, but for other use s including

flood cont r o l and navigation as wel l. The

largest hydro development in t he world ,

Three Gorge s in China, for examp le has

been designed to provide much needed

power to China but to also upgrade the

flood control standard of the middle and

lower reaches of the Yangtze riv er, and

improve navigation for large ships. Such an

achievement – although largely controver-

sial as a result of the resettlement policy and

environmental issues – would have b een

unthinkable in the early days of the journal.

The first edition of Water Power included

articles on the power resources of Europe,

new developments in civil engineering, the

design of water intakes and surge tanks, a

review of large s chemes in Canada, and

details on hydro devel opments in

Australisia. We’ve tried t o include similar

themes in this anniversary issue to highlight

growth. For example, we look at new pro-

jects in Canada and Australia in our tun-

nelling section , while detailing new

engineering aspects of small hydro schemes

in our ‘Best of the best’ feature, while also

highlighting some of the most important

dam projects in Europe and Africa, and the

impact they have mad e on the dam engi-

neering industry.

Over the years, new techniques have been

developed that made hydro power and dam

construction more efficient and faster,

including the introduction of roller com-

pacted concrete; new markets have opened

up, including South America and Asia, while

refurbishment schemes play a bigg er role

today than they ever have. All these devel-

opments and more have been highlighted by

members o f the industry in ou r special

anniversary report on p28. If there are any

memories you would like to share, please let

me know via email: cstocks@progressive-

mediagroup.co m. I ’ll be p osting a specia l

section online at www.waterpowe rmaga-

zine.com which will include r eaders views

on the last six decades of hydro.

We will also continue to report on these

important developments in IWP&DC and

want to ensure that the journal remains your

forum. In the words of the journ al’s first

editor: “Thus we go forward with con fi-

dence in Water Power, supported by all who

have faith in the gigantic schemes of man’s

undertaking – and we hope to contribute

expert knowledge on the subject, while pro-

viding a medium for the exchange of views

among all concerned with its planning,

development and use.’

Carrieann Stocks, Editor

60 years of

water power…

Let none run to waste

IWP& DC

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM MAY 2009 27

60TH ANNIVERSARY

28 MAY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

60TH ANNIVERSARY

Highlighting hydro

developments

Members of the hydro industry reflect on the major

developments in the industry over the past six decades

and comment on important issues for the future

A

L

ESSAND RO

P

A

LMIERI

,

L

E

AD

D

A

M

S

P

ECIALI ST

,

W

ORLD

B

ANK

The process initiated by the World

Commission on Dams (WCD) has been

the most relevant change in the la st

decade. After three years of WCD, and six

years of the UNEP’s led Dams and

Development Project (DDP), the latter

project came to an end in June 2007. The

compendium Dams and Developm ent:

Relevant Practices for Improved Decision-

Making

(www.unep.org/dams/includes/compendiu

m.asp) represented DDP’s main output.

The following is an excerpt from

UNEP’s covering letter to the compendium:

‘This publication departs from the

approach followed by most literature on

dams which tends to focus on shortcom-

ings and failures. Instead it presents prac-

tices that, tho ugh not exempt from

weaknesses, show a positive or progressive

way of doing things.’

This is a remarkable st atement which

departs from the sharp critique of an

alleged worldwide ‘business as usual

approach’ portrayed in the WCD report.

Whether that was a WCD flaw, or if sig-

nificant progress has occurred after that

report, is not clear and not so relevant

anyway. The substance is that a positive

message on improved decision-ma king

came out of the DDP exercise.

From a technolog ical point of view,

hydro power is a very mature indu stry

and, as such, very reliable. Its renewable

nature gives hydro power, and especially

hydro power with storage, an enormous

importance in helping humankind to limit

the use of fossil fuels which is the real

cause of excessive releases of greenhouse

gases into the atmosphere.

In the challenging endeavour of curbing

excessive emissions, hydro power is the

ideal partner of other renewable e nergy

sources which do not have the same relia-

bility of supply. I have no doubt that syn-

ergy between hydro and wind, hydro and

solar, solar and geothermal, etc will play a

significant contribution to greenh ouse

reduction and sustainable development.

Technology is far from being a barrier

to that goal. The real barrier is the minds

of many, often important policy makers,

who view hydro as an ‘alternative’ to

other renewable energy sources. When

these people will be able to open up their

minds and realise the huge synergetic

opportunities , we will have made a b ig

step forward.

IWP&DC can contribute to make this

happen, and I am confident it will.

A handful of interna tional magazines

bring relevant information about dams

and hydro power to the interested audi-

ence. IWP&DC is th e one that has done

this for the longest time. To the merit of its

editors, the magazine h as b een able to

adapt itself to the changes of demand and

supply trends in water and energy.

For IWP&DC, age ha s gone hand-in-

hand with innovation and the ability to

adapt the con tents of the articles to the

changes that have o ccurred i n the sector

during the last decade or two.

Email: Apalmieri@worldbank.org

The views expressed in this note are entirely those of

author and should not be attributed in any manner to

the World Bank, to its affiliated organisations, or to

the members of its Board of Executive Directors, or

the Countries they represent.

K

ENNETH

D. H

ANSEN

P.E.,

C

ONSULTING

E

NGINEE R

In my view, the birth of the roller com-

pacted concrete (RCC) dam has been the

single most important development in

dam engineering in the past 30 ye ars.

This opinion is shared by many others.

With respect to dam construction in the

early 1970’s, more and more embank-

ment dams were being built at sites that

could accommodate a concrete dam. This

w

as mainly because they cost less. Earth

moving construction methods had

advanced more rapidly than concrete con-

struction methods. Mass concrete dams

continued to be placed in large monoliths,

called blocks, bucket by bucket, like

Hoover Dam in the early 1930’s.

Still, earth dams had problems. They

were more prone to failure, mainly due

to overtopping during a flood or due to

internal erosion, called piping. Concrete

dams continued to have an excellent per-

formance record. Only one recorded

concrete dam has failed in the US during

the past 80 years for any reason.

Both structural and geotechnical engi-

neers were thus seeking a way of solving

the problem of producing a concrete dam

at less cost, while maintaining its inher-

ent safety. This is what brought about the

innovation of the RCC dam.

While quite a few ex amples of early

dam projects using RCC have emerged,

I feel three projects stand out. They are

the use of 2.7Mm

3

of what was called

“rollcrete” for the rehabilitation of Tarbela

dam in Pakistan between 1974 and 1986

together with the completion of

Shimajigawa Dam in Japan and Willow

Creek Dam in the US in the early 1980’s.

Much has been learned from the pio-

neering designers of early RCC dams

with respect to seepage control, cracking,

and stability. This has led to a high degree

of acceptance of RCC dams throughout

the world. By the end of 2008, the

number of completed RCC dams greater

than 15m high is nearing 400. They were

built in 46 counties on six continents.

RCC dams are now being built higher,

larger and at greater speed. Longtan

Dam in China will soon be completed to

a height of 216.5m, while tenders for the

272m high Diamer Basha dam in

Pakistan are expected this year.

Thus, a new dam type or more correct-

ly a new dam construction method was

developed by innovative engineers identi-

fying a problem and coming up with a

solution. However, the early designs were

not without problems along the way.

These early pioneers in the birth of RCC

dams are due a high degree of gratitude

by those who followed in building RCC

better, higher and faster.

Email: ken@ken-hansen.com

60TH ANNIVERSARY

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM MAY 2009 29

I

NTERNATIONAL

C

ENTRE FOR

H

YDROPO WER

, N

ORWAY

Laura Bull is the head of studies at the

International Centre for Hydropower

(ICH) in Norway. As we celebrate the past

60 years her hydro focus is very much on

the future. Here she explains how the ICH

is helping to meet the ever-changing chal-

lenges imposed upon the hydro industry.

Risk management in general is a process

aimed at an efficient balance between real-

ising opportunities for gains, and minimis-

ing vulnerabi lities and loss es. It is an

integral part of management practice and

an essential element of good corporate gov-

ernance.

1

Every activity which mankind involves

itself in is susceptible to suffering events,

which ca n have a negative impac t.

Throughout history we have been imple-

menting methodologies which allow us to

confront these threats. Based on our intu-

ition, we have developed technology to this

end. Risks exist within decision-making as

well as within the normal development of

activities in every working enterprise; and

indeed all organisations are ex posed to

these risks.

The hydro power industry is no excep-

tion. Energy efficiency has been determined

by risk manage ment and it has become

vital; in view of the international financial

crisis and the very real challenges which cli-

mate change presents fo r water manage-

ment. This is in addition to the

contemporary political processes and the

activities of regional integration in several

continents, where the relations country to

country are a key parameter for hydropow-

er generation.

In accordance with ICH’s interdiscipli-

nary training, we have established the

Hydropower Risk Management Course for

2010 which will embrace an integral analy-

sis, in order to meet the needs of the ever-

changing world.

The course’s specific objectives are to:

• Create awareness of ne w international

trends of risk management in the hydro

power development process.

• Develop the participant’s abili ty to

identify, qu alify, evaluate and design

measurements to monitor and manage

the different risks on a strategic level.

• Enable participants to implement method-

ologies in their own socio-cultural

context.

The course aims to give a global vision of

risk assessme nt for hydropower. It will

update and familiarise participants with the

new concepts and will be led by a team of

international experts.

Through courses such as this, ICH con-

tinues in its work to help develop compe-

tence and raise the standards o f hydro

industry personnel. For more detailed infor-

mation regarding ICH courses please con-

tact: Laura C. Bull Head of Studies at ICH.

laura@ich.no. To subscribe to ICH’s

monthly newsletter visit www.ich.no

[1] ENISA, European Network and

Information Security Agency. 18/06/06

30 MAY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

60TH ANNIVERSARY

E

UROPEA N

S

MALL

H

YDROPO WER

A

SSOCIATION

As IWP&DC marks its 60th anniversary,

2009 will also be a s pecial milestone

for the European Small Hydropower

Association (ESHA).

ESHA has represented the interests

of the SHP sector in the European

Union since 1989 when it wa s created

throu gh an in itiative of the European

Commission. In 2000, ESHA decided to

j

oin its colleague s represent ing other

renew able energy sectors in the

Renew able Energy House in Belgium.

The representation of a Secretariat in

Brussels has helped to improve the image

of the sector and aid its development

through lobbyin g activi ties at different

EU levels.

The small hydro industry has faced

many c hallenges over the past 20 years.

SHP in the EU context is defined as cov-

ering plants with an installed capacity

up to 10MW. Even if in quantitative

terms the sector represents only a small

part of renewable energy production, it

offers much po tentia l and great scope

for deve lopmen t. It has an important

contribution to make to EU energy

needs through:

• Combining with other renewables.

• Integrating in multipurpose systems.

• Upgrading and refurbishing existing sites

in the EU.

In additio n the latest policy dev elop-

ments, with th e newly adopted RES

Directive paving the way for 20% renew-

able energy by 2020 , wil l bri ng a new

d

rive for sustainable hydro power devel-

opment. Furthermor e, those linking

water and ener gy as precious intercon-

nected resources have identified small

hydro as a reliab le supplier of electricity

generation, especially for rural p opula-

tions without access to grid electricity.

The past 20 years have served to position

the small hydro sector and make it speak

with one voice, underlining its beneficial

use. On the technological side, improve-

ments have been made on more efficient

and less costly turbines but the largest

efforts have been in developing more appro-

priate turbines, such as fish-friendly and

very low head turbines.

ESHA’s 20th anniversary will be a great

opportunity to remember all these aspects,

to celebrate achievements, but also to think

about the future. Much is still pending and

many challenges are ahead. Times are

changing and we have to change with them.

We need to think now about ESHA’s con-

tribution to facilitate the reaching of the

2020 targets and to represent the interest of

sustainable hydro power within the renew-

able energy family. This will enable us to

contribute to the EU’s security of energy

supply, to economic development as well as

to the abatement of climate change.

www.esha.be

N

ATIONAL

H

YDROPOWER

A

SSOCIATION

The National Hydropower Association

in t he US is pleased to congrat ulate

International Water Power & Dam

Construction on 60 years of ser vice in

helping the hydro power industry stay

connected on a global scale. Through the

magazine, hydro power interests around

the world hav e had th e opportunity to

follow our indu stry’s successes, best

p

ractices, and challenges.

This is an exciting time for the hydro

power industry. In the US, where we

have marked more than 125 years o f

hydroelectric generation, we’re at the

beginning of a new era that is already

seeing new technologies and new oppor-

tunities become available. This year start-

ed off with the licensing of the first

commercial US hydrokinetic facility, and

we anticipate many more milestones,

especially as policies favourable to hydro-

electric development and federal research

and development come to fruition.

As NHA looks to th e future, we see

another century of hydro power ahead.

We’re confident that IWP&DC will be

there to report on and continue to serve

the international hydro power industry

for many years to come.

The NHA’s annual conference will

be held in Washington DC from 11-13

May 2009.

www.hydro.org

F

RED

A

YER

, E

XECUTI VE

D

IRECTO R

, L

OW

I

MPACT

H

YDROPO WER

I

NSTITU TE

The c h anges tha t have taken place in the

US hydro regulatory arena since I started

working with the Federal Power

Commission, later renamed the Federal

Energy Regul a t o ry Commission (FERC),

are many. In 1974, I was a draftsman for a

small Pittsfield, Maine engineering com-

pany that had a few hydro clients. One day

one of the partners asked me to take on a

new assignment and deal with ‘r ed tape’

created by a bunch of bureaucrats in

Washington. He assured me that it

shouldn’t take more than five hours a

week, tossed me a

copy of the Federal

Power Act, and

wished me luck!

Since that time I

have spent almost

my entire caree r

working on hydro

licensing and reli-

censing projects as a

consultant, a hydro

utility employee,

and most recently head of a small non-

profit low impact hydro certifi cation

organisation.

When I started, the environmental

statutes that drive much of the complexity,

contention, and decision-making associat-

ed with l icensing and perm itting hy dro

projects were in their infancy. They were

also poorly und erstood by most of us

trying to work w ith them. It was a time

when people who owned and opera ted

hydro projects (mostly utilities of one stripe

or anot her and a relatively small contin-

gent of industrial operators) did not feel

they had an obligation to consult with the

resource agencies or the public.

The burgeoning interest in hydro devel-

opment during the late 1970s created a

flood of preliminary permits, five to six

times more than normal. This hydro ‘gold

rush’ became the focus of disenfranchised

stakeholders. During this period, FERC lost

court battles and stakeholders were suc-

cessful in getting Congress to listen. This led

to major changes in FERC regulations

requiring hydro owners to consult with, and

pay heed to, non-developmental interests.

The hydro industry’s reaction to the

increased transparency and requirements to

consult was not a positive one. They resist-

ed the changes. Meanwhile the NGOs and

state and federal resource agencies began to

understand the importance of becoming

active participants in the FERC regulatory

process as a way to meet their goals. Some

licences took many years, and many

lawyers, to resolve. These were sometimes

in the licensee’s favour but more often than

not in the favour of a tribe, state or NGO.

Licensing had become very expensive and

lacked any kind of certainty.

Finally, wiser heads prevailed and friend

and foe worked together to find ways to fix

a system that they all agreed was broken.

Forward thinking licensees and other stake-

holders began to explore a variety of ways

to resolve these multi-party disputes over

the proper use of the resources. New words

like settlement, adaptive management, and

collaborative task force became part of the

hydro regulatory lexicon. We had arrived.

Today there are still disagreements, but

they don’t go to court as often as they once

did. And now it is not unusual for stake-

holders who participated in the settlement

agreement to become ‘partners’ who stay

actively involved in the project.

Email: fayer@lowimpacthydro.org