Water Power and Dam Construction - Issue February 2009

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM FEBRUARY 2009 21

PROJECT COSTS

equipment in powerhouses which feature Pelton, Francis, Kaplan,

Kaplan-Rohr (for low heads up to 15m), Bulb or Francis pump tur-

bine units have been developed based on the compilation of statis-

tical data for over 81 hydro power projects. The data was obtained

from existing publications, journals, call for tenders, award of ten-

ders, websites and suppliers of E&M equipment. The data also con-

tains projected costs from some projects – found on existing reports

or national authority references.

C

OMPILED DATA

The compiled data corresponds to information of the E&M contracts

for powerhouses only, which include costs of turbines, governors,

valves, cooling and drainage water systems, cranes, workshops, gen-

erators, transformers, earthing systems, control equipment, telecom-

munication systems (including remote central control room) and

auxiliary systems (including draft tube gates, heating and ventilation,

domestic water and installation). Other electrical and mechanical

M

ANY mathematical formulae (Gordon-Penman, 1979;

Nachtnebel, 1981; Gordon, 1981, 1983; Gordon-Noel,

1986; Aggidis-Luchinskaya-Rothschild-Howard, 2008)

have been developed for estimation of costs, or gener-

ating costs, of small and large hydro power projects. These often

focus on specific topics such as costs of the dam type, tunnelling

work, penstock installation, civil works for powerhouses, electrical

and mechanical equipment for powerhouses, etc. Focusing on E&M

equipment, the existing formulae have been developed taking into

account specific cost data for a region or country, while also consid-

ering global costs of planning a hydro plant.

When working on a project, hydro consultants need to carry out a

cost estimation analysis for each specific case. This can be a time-con-

suming task when carrying out feasibility studies and final reports.

Therefore, a detailed analysis of costs continually needs to be carried

out. The author has developed a simplified methodology based on

current information from E&M equipment contractors or suppliers.

Useful diagrams which allow a close cost e stimation of E&M

Estimating E&M powerhouse costs

The cost includes turbines, governors, valves, cooling and

drainage water systems, cranes, workshop, generators,

transformers, earthing system, control equipment,

telecommunications systems and auxiliary systems.

Austria

Congo

Germany

Laos

Nicaragua

Rep. Dominicana

South Africa

USA

Canada

Ecuador

Iceland

Madagascar

Pakistan

Rwanda

Sudan

Brazil

Argentina

Chile

El Salvador

Iran

Mexico

Peru

Romania

Turkey

Armenia

China

Ethiopia

Kenya

Nepal

Portugal

Russia

Uganda

1000

1000

100

10

1

1

10 100 1000 10000

P [MW]

Cost [US$ x 10

6

]

Cost of electrical and mechanical

equipment in a powerhouse

(data series 2002-2008)

Valid for 2009

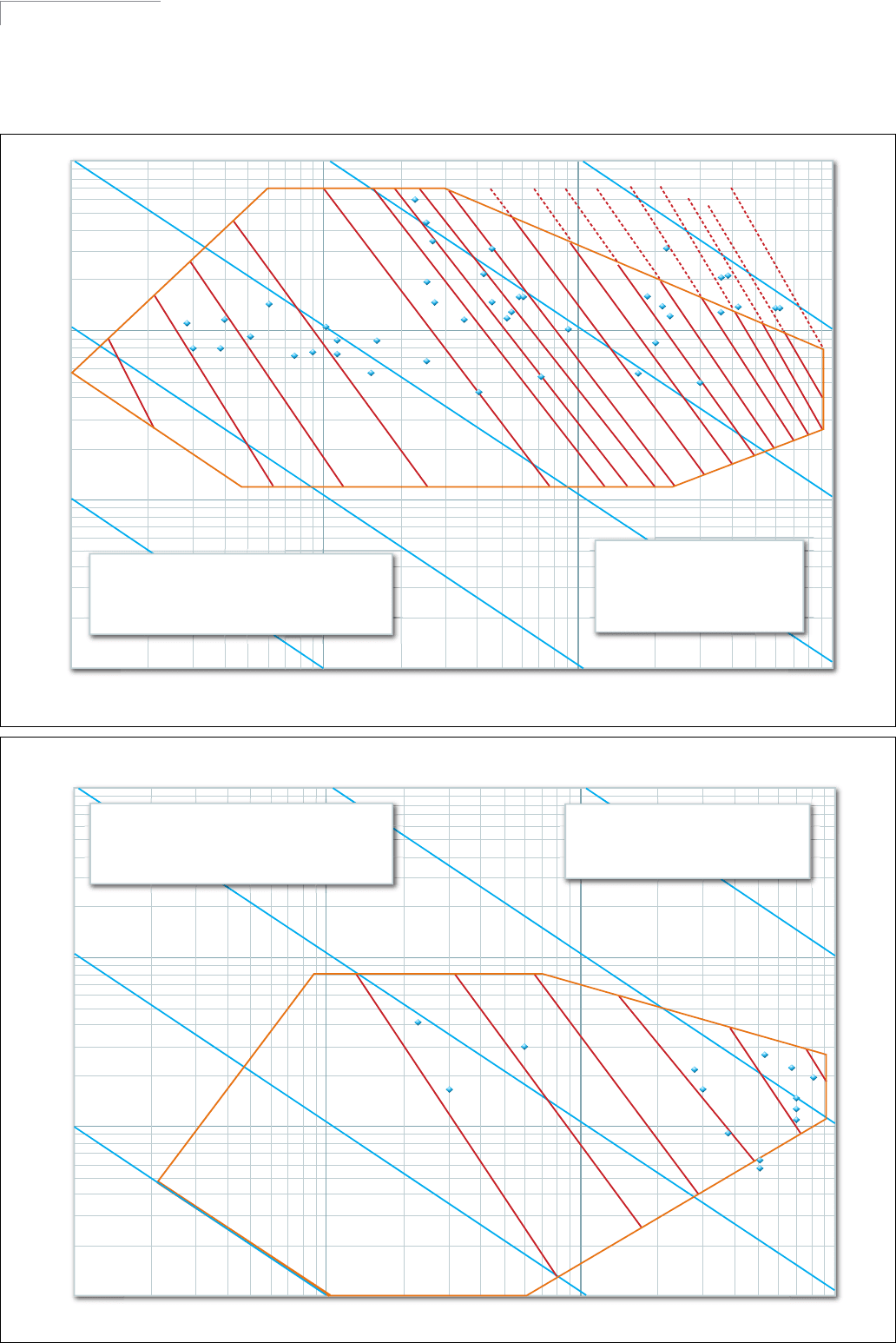

After compiling statistical data on costs of electrical and mechanical equipment for 81 selected

hydro power projects (60% 2007-2008 and 40% 2002-2006), useful diagrams which allow a

close cost estimation of E&M in powerhouses with Pelton, Francis, Kaplan, Kaplan-Rohr, Bulb

turbine or Francis pump turbines have been composed. Paper by Cesar Alvarado-Ancieta

Figure 1: Costs of E&M equipment and installed power capacity in powerhouses for 81 hydro power plants in America, Asia, Europe and Africa

22 FEBRUARY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

PROJECT COSTS

equipment not suitable for use in powerhouses are not included. The

global amount of contracts obtained from suppliers comprises the

items mentioned above with a few exceptions (mainly due to the fact

that some suppliers only provide either electrical and mechanical

equipment and not both). However, these main suppliers are always

in consortium – meaning the global cost of E&M is not affected.

The data, which is presented on Table 1, corresponds to 81 hydro

power projects in 32 countries. The data comprises approximately

28 hydro power projects in America (90% Latin America), 9 in

Europe, 35 in Asia and 9 in Africa. From these, 33 are from 2007

and 16 from 2008. The remaining 40 corresponds to the period

between 2002 and 2006.

The hydro plants have net heads ranging from 9m to 800m and

power capacities from 0.5MW up to the 800MW per unit. Taking into

account the cost inflation over the past few years, the costs of E&M

equipment for the period 2002-2008 have been revised and updated.

These include different factors such as price of metals, project region,

index of prices, exchange rates, escalation of prices and cost confidence.

M

ETHODOLOGY

The result of this analysis is the availability of 81 points to be plot-

ted with data on installed power capacity (P in MW), net head (H in

m), design discharge (Q in m

3

/sec), number of units and total costs

of E&M equipment (Cost in million US$) in order to provide 81

points per generating unit. These are divided by type of turbine:

Pelton, Francis, Kaplan, Kaplan-Rohr, Bulb or Francis pump-turbine.

Figure 1 shows the 81 points available on E&M equipment plot-

ted by global costs and installed power capacity. A general tenden-

cy is found as a function of the power capacity, which serves as a

reference for estimation of E&M equipment in generating costs

under the proposed formula:

Cost = 1.1948P

0.7634

Generating cos t for E&M equipment in

Million US$, 12/2008.

where P is the power or installed capacity in MW.

Formulae based on parameters such as head, design discharge,

power and/or number of units have a large range of variablity in the

result of costs, therefore they should be limited depending on dif-

ferent range of heads, discharge, etc. These type of formulae cannot

be easy applied for cost estimation of E&M equipment of the dif-

ferent type of units. Therefore, the methodology fol lo w e d here is

based on the appliance of cost estimation diagrams, which are con-

sidered more suitable taking into consideration the parameters avail-

able for a hydro plant.

In order to plot the data the envelope curves for the th ree main

types of turbine were defined accord ing to available information

from manufacturers. The rated f low and net head determine the

se t of turbine types applicable to the site and the flow environ-

ment. Suitable turbines are those for which the given rated f low

and net head plot with in the operational envelopes (the envelope

curves are described on Figures 2, 3, 4 a nd 5). A point defined as

above by the flow and the head will usually plot within several of

these envelop es. It should be remembered that the envelopes vary

from manufacturer to manufacturer and those plotted here are the

usual operat ional envelope curve for Pelton, Francis, Kaplan,

Kaplan-Rohr and Bulb turbines. Together with the defined enve-

lope curves for the range of head and discharges, the additional

scale for installed power has been plotted. This means the para-

meters of head (H), discharge (Q) and power (P) are available for

each plotting position. These are defined tog ether with a cost per

unit. The different points define the probable curve of cost among

the available po ints.

D

IAGRAMS FOR ESTIMATING

E&M

EQUIPMENT COSTS

Costs of E&M equipment for hydro plants with Pelton units

The available data comprises 20 plotting positions for HPPs

with Pelton units (see Figure 2). The range for determination

of costs starts from a lower cost of US $0.5M for an i nstalled

power below 1MW to an upper cost of US$60M for 200M W

installed power.

2.80 M$

7 MW

1 MW

0.1 MW

0.1 MW

10 100 10001

1 MW

Q [m

3

/s]

2.68 M$

5.35MW

5.25 M$

25 MW

13.65 M$

60.5 MW

17.75 M$

79.30 MW

20.05 M$

65 MW

11.78 M$

16.85 MW

8.33 M$

12.67 MW

13.50 M$

40 MW

21.43 M$

65 MW

0

.82 M$

2.5 MW

2.52 M$

4.85MW

12.15M$, 25 MW

38 M$,150 MW

38.90 M$,170 MW

32.5 M$,110 MW

29.93 M$,105 MW

53.57 M$,99 MW

58 M$,70 MW

21M$,25 MW

H [m]

10 MW

10 MW

100 MW

100 MW

1000 MW

1000 MW

The cost includes turbines, governors,

valves, cooling and drainage water systems,

cranes, workshop, generators, transformers,

e

arthing system, control equipment,

telecommunications systems and auxiliary systems.

0.5

2

3

5

10

15

20

30

40

50

60 Mio US$

1

Mio US$

Cost of electrical and mechanical

equipment in a powerhouse per

u

nit with a Pelton Turbine

(data series 2002-2008)

Valid for 2009

1000100101

Figure 2: Costs of E&M equipment in powerhouses per unit with Pelton turbine

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM FEBRUARY 2009 23

PROJECT COSTS

Table 1 – Hydro power parameters and E&M cost statistics for data

series, years 2002-2008.

# Year Country Hydropower Power Unit Net Head Design Unit E&M Contract/ E&M Updated Contract/ Type of # of E&M Updated Cost

Project P [MW] Power H [m] Flow Q Flow Qu Projected Cost 12/2008 Tubine units 12/2008 [Mio. US$]

Pu [MW] [m3/s] [m3/s] Cost [Mio.] [Mio. US$] per Unit

[US$] [EUR]

1 2008 Peru Pucara 130 65 475 30 15 40 0 42.86 Pelton 2 21.43

2 2007 Cheves III 212 106 443 50 25 45 0 49.01 Francis 2 24.50

3

2004 Poechos I 15.4 7.7 42 45 22.5 12 0 14.40 Kaplan 2 7.20

4

2007 Poechos II 10 5 17 60 30 8 0 8.57 Kaplan 2 4.29

5

2008 Machu Picchu II 99 99 345 32 32 50 0 53.57 Pelton 1 53.57

6 2008 Santa Rita 255 85 220 126 42 77 0 80.00 Francis 3 26.67

7 2006 El Platanal 220 110 600 45 22.5 0 25 65.00 Pelton 2 32.50

8 2006 Nicaragua Larreynaga 17 8.5 90 22 11 11.2 0 12.92 Francis 2 6.46

9 2008 El Salto YY 25 12.5 90 32 16 16 0 16.00 Francis 2 8.00

10 2008 Pakistan Daral Khawar 38 12.7 293 19.5 6.5 25 0 25.00 Pelton 3 8.33

11 2003 Allai Khwar 121 60.5 662 21 10.5 21.8 0 27.30 Pelton 2 13.65

12 2003 Duber Khwar 130 65 516 29 14.5 32 0 40.10 Pelton 2 20.05

13 2007 Madian 160 80 160 116 58 51.6 0 55.29 Francis 2 27.64

14 2006 Gabral Kalam 135 45 200 75 25 36 0 41.59 Francis 3 13.86

15 2007 Turkey Umut-1 4.1 2.1 81 6 3 2.2 0 2.40 Francis 2 1.20

16 2007 Umut-2 22.1 7.4 145 18 6 12 0 12.86 Francis 3 4.29

17 2007 Umut-3 11.8 5.9 77 18 9 8 0 8.57 Francis 2 4.29

18 2007 Ege-1 8.2 2.7 114 8.5 2.8 3.8 0 4.11 Francis 3 1.37

19 2007 Ege-2 7.8 2.6 80 11.4 3.8 3.4 0 3.60 Francis 3 1.20

2

0 2007 Ege-3 11.9 4.0 93 15 5 5.8 0 6.17 Francis 3 2.06

2

1 2007 Yaprak-1 9.69 4.8 81 8 3 4.7 0 5.04 Pelton 2 2.52

22 2007 Yaprak-2 10.7 5.4 144 9 3 5 0 5.36 Pelton 2 2.68

23 2007 Basak 6.85 3.4 120 10 4 3.5 0 3.75 Francis 2 1.88

24 2007 Tuna 33.7 16.9 502 20 10 15.2 0 23.56 Pelton 2 11.78

25 2007 Uzuncayir 96 32 55 210 70 0 33 49.43 Francis 3 16.48

26 2008 Ilisu 1200 400 130 1080 360 0 164.5 246.75 Francis 3 82.25

27 2007 Borcka 300 150 87.5 600 200 0 67.6 101.26 Francis 2 50.63

28 2008 Akocak 80 40 250 23 11.5 0 18 27.00 Pelton 2 13.50

29 2007 Akkoy I 103.5 34.5 149 81 27 0 24.7 37.00 Francis 3 12.33

30 2008 Laos Nam Pha 120 60 130 108 54 49.5 0 49.50 Francis 2 24.75

31 2007 Rwanda Nyabarango 29 14.5 66.5 50 25 16.9 0 18.05 Francis 2 9.03

32 2005 Madagascar Sahanivotry 14 7 240 7 3.5 3.5 0 5.60 Pelton 2 2.80

33 2007 South Africa Lima 1520 380 629 140 70 372.3 0 398.89 Francis-pump 4 99.72

34 2008 Nepal Upper Tamakoshi 317.2 79.3 802 44 11 71 0 71.00 Pelton 4 17.75

35 2002 Middle Marsyangdi 72 36 120 70 35 0 20 29.90 Francis 2 14.95

36 2007 Kenya Tana1 11 5.5 73 15 7.5 8.4 0 9.00 Francis 2 4.50

Tana2 15.2 7.6 58 30 15 12.6 0 13.52 Francis 2 6.76

37 2005 Armenia Gegharot 2.5 2.5 297 1 1 0.8 0 0.82 Pelton 1 0.82

38 2008 Austria Obervellach II 50 25 795 17.6 8.8 0 16.2 24.30 Pelton 2 12.15

39 2006 Limberg II 480 240 365 144 72 0 33 80.85 Francis-pump 2 40.43

40 2004 Kopswerk II 450 150 800 72 24 0 60 114.00 Pelton-pump 3 38.00

41 2007 El Salvador Cerrón Grande, Unit 3 87 87 57 170 170 42 0 45.00 Francis 1 45.00

42 2008 Chile Lircay 19 9.5 106 20 10 12 0 12.00 Francis 2 6.00

43 2007 La Confluencia 163.2 81.6 344 52.5 26.3 37.5 0 39.99 Francis 2 20.00

44 2007 Ecuador Pilatón-Sarapullo 50 25 120 45 22.5 39.2 0 42.00 Pelton 2 21.00

45 2007 Toachi-Alluriquín 140 70 191 82.4 41.2 108.2 0 115.93 Pelton 2 57.96

46 2007 Mazar 162 81 162 120 60 0 39.9 59.77 Francis 2 29.89

47 2007 Abitagua 220 55 123 206 51.5 88.8 0 95.14 Francis 4 23.79

48 2005 Germany Rheinfelden 114 28.5 9.2 1500 375 0 52 78.00 Kaplan-Rohr 4 19.50

49 2006 Waldeck I 74 74 200 28 28 0 24 35.88 Francis-pump 1 35.88

50 2007 China Jinping II 4800 600 318 1760 220 0 120 567.96 Francis 8 71.00

51 2004 Three Gorges Right Bank 2800 700 138 2400 600 198 0 440.00 Francis 4 110.00

52 2006 Caojie 512 128 20 3220 805 0 51 153.00 Kaplan 4 38.25

53 2008 Dagang-shan 2600 650 210 1440 360 0 75 336.00 Francis 4 84.00

54 2005 Xiaowan 4284 714 216 2280 380 0 60 540.00 Francis 6 90.00

55 2003 Longtan 4900 700 140 4095 585 0 81 700.00 Francis 7 100.00

56 2006 Brasil Anta 28.8 14.4 30 118 59 25.7 0 29.64 Kaplan 2 14.82

57 2002 Pedra do Cavalo 165 82.5 105 180 90 0 32 64.00 Francis 2 32.00

58 2002 São Salvador 250 125 22.8 1340 670 0 30 75.00 Kaplan 2 37.50

59 2008 San Antonio 3150 72 13.9 28600 650 318* 0 365.76 Bulb 12 30.48

60 2008 Jiraú 3300 75 15.1 27500 625 636* 0 636.00 Bulb 19 33.47

61 2007 Iceland Kárahnjukár 690 115 600 135 22.5 0 99 148.30 Francis 6 24.72

62 2006 Canada Revelstoke, Unit 5 512 512 145 400 400 82.6 0 95.26 Francis 1 95.26

63 2007 Por tugal Picote II 248 248 125 230 230 0 46 69.00 Francis 1 69.00

64 2008 Alqueva II 260 130 72 406 203 0 94 141.00 Francis-pump 2 70.50

65 2008 Romania Lotru-Ciunget 510 170 800 75 25 0 77.8 116.70 Pelton 3 38.90

66 2005 Congo Imboulou 120 30 17 1200 300 69 0 87.63 Kaplan 4 21.91

67 2007 Uganda Bujagali 255 51 22 1375 275 87 0 113.10 Kaplan 5 22.62

68 2007 Argentina Los Caracoles 125.2 62.6 150 90 45 45 0 48.21 Francis 2 24.11

69 2006 Sudan Merowe 1250 125 50 3000 300 0 250 525.00 Francis 10 52.50

70 2005 Gilgel

Gibe II 420 105 487 92 23 0 60 119.70 Pelton 4 29.93

71 2004 Ethiopia Beles 460 115 308 180 45 0 77 115.50 Francis 4 28.88

72 2007 Iran Sia Bishe 1000 250 500 224 56 0 64.5 193.24 Francis-pump 4 48.31

73 2002 Karen IV 1020 255 162 740 185 0 22 239.80 Francis 4 59.95

74 2002 Upper Gotvand 1016 254 141 840 210 0 23 248.40 Francis 4 62.10

75 2007 Russia Uglich 70 70 12 700 700 0 24.9 32.37 Kaplan 1 32.37

76 2008 Motygin-skaya 1250 125 27 5250 525 0 350 350.00 Kaplan 10 35.00

77 2008 USA Cannelton 84 28 6.5 1500 500 0 40.9 61.35 Rohr 3 20.45

78 2008 Smithland 72 24 5.9 1500 500 0 39.6 59.37 Rohr 3 19.79

79 2005 Rep. Dominicana Pinalito 50 25 590 10 5 0 7 10.50 Pelton 2 5.25

80 2008 Mexico El Gallo 30 15 44 80 40 18.7 0 19.80 Francis 2 9.90

81 2008 Chilatán 14 7 75 22 11 11.7 0 12.40 Francis 2 6.20

Reference sources for contract costs were existing publications, journals, calls for tenders, websites of E&M equipment suppliers

Reference sources for pr ojected costs were existing reports of studies and national authorities.

The contract cost for San Antonio and Jiraú is for 12 and 19 units respectively.

24 FEBRUARY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

PROJECT COSTS

1 MW

0.1 MW

0.1 MW

10 100

100

9

0

80

70

6

0

50

40

302520151052

0.5

1 Mio US$

110

120 Mio

US$

10001

1 MW

Q [m

3

/s]

1.37 M$, 2.7 MW

1.2 M$, 2.07 MW

1.2 M$, 2.59 MW

1.88 M$, 3.43 MW

2.06 M$, 3.95 MW

4.5 M$, 5.5 MW

4.29 M$, 5.88 MW

6.21 M$, 7 MW

6.46 M$, 8.5 MW

6 M$, 9.5 MW

13.86 M$, 45 MW

24.72 M$, 115 MW

24.5 M$, 106 MW

20 M$, 81.6 MW

28.88 M$, 115 MW

26.67 M$, 85 MW

29.89 M$, 81 MW

7

1 M$, 600 MW

2

4.75 M$, 60 MW

62 M$, 254 MW

50.63 M$, 150 MW

6

0 M$,

255 MW

27.64 M$, 80 MW

6.76 M$, 7.6 MW

8 M$, 12.5 MW

9 M$, 14.5 MW

12.33 M$, 34.5 MW

14.95 M$, 36 MW

24.11 M$, 62.6 MW

23.79 M$, 55 MW

16.48 M$, 32 MW

32 M$, 82.5 MW

100 M$, 700 MW

110 M$, 700 MW

45 M$, 87 MW

69 M$, 248 MW

52.5 M$, 125 MW

82.25 M$, 400 MW

95.26 M$, 512 MW

9.9 M$,15 MW

4.29 M$, 7.37 MW

H [m]

10 MW

10 MW

100 MW

100 MW

1000 MW

1000 MW

T

he cost includes turbines, governors,

valves, cooling and drainage water systems,

cranes, workshop, generators, transformers,

e

arthing system, control equipment,

telecommunications systems and auxiliary systems.

90 M$, 714 MW

84 M$, 650 MW

Cost of electrical and mechanical

equipment in a powerhouse

per unit with Francis Turbine

(data series 2002-2008)

valid for 2009

1000100101

The cost includes turbines, governors,

valves, cooling and drainage water systems,

cranes, workshop, generators, transformers,

earthing system, control equipment,

telecommunications systems and auxiliary systems.

5 Mio US$

40 Mio US$

10 15

20

30

0.1 MW

1 MW

0.1 MW

10 100 10001

1 MW

Q [m

3

/s]

7.20 M$,

7.7 MW

14.82 M$, 14.4 MW

22.62 M$, 51 MW

35 M$,

125 MW

37.5 M$,

125 MW

38.25 M$, 128 MW

3

2

.

3

7

M

$

,

7

0

M

W

20.45 M$,

28 MW

19.79 M$,

24 MW

19.50 M$,

28.5 MW

21.91 M$, 30 MW

33.47 M$, 72 MW

30.48 M$, 75 MW

5.36 M$,

5 MW

H [m]

10 MW

10 MW

100 MW

100 MW

1000 MW

1000 MW

Cost of electrical and mechanical

equipment in a powerhouse per unit

with Kaplan, Kaplan-Rohr, Bulb Turbine

(data series 2002-2008) Valid for 2009

1000100101

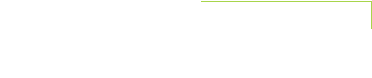

Figure 3: Costs of E&M equipment in powerhouses per unit with Francis turbine

Figure 4: Costs of E&M equipment in powerhouses per unit with Kaplan, Kaplan-Rohr and Bulb turbine

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM FEBRUARY 2009 25

PROJECT COSTS

Costs of E&M equipment for hydro plants with Francis units

The available data comprises 43 plotting positions for plants

equipped with Francis units (Figure 3). The determination of costs

ranges from US$0.5M for 1MW installed capacity up to a maxi-

mum cost of US$120M for an 800MW plant.

Costs for hydro plants with Kaplan, Kaplan-Rohr, Bulb Units

The available data comprises 14 plotting positions for plants

equipped with Kaplan/Rohr/Bulb units (see Figure 4). The range for

determination of costs on E&M equipment starts from a lower cost

of US$5M for an installed power of 5MW up to US$40M for an

installed power of 150MW.

Costs hydro plants with Francis pump-turbine units

The availabl e data comprises five p lotting positions for p lants

equipped with Kaplan, Kaplan-Rohr and Bulb units (Figure 5). The

range for determination of costs on E&M equipment starts from a

lower cost of US$20M for an installed power of 70MW up to

US$70M for installed power of 380MW.

C

ONCLUSIONS

• Diagrams have been developed to estimate water to wire power

plant equipment costs within an accuracy of 5 to 10 %.

• Equipment costs are currently escalating at about 8 to 10% per

annum for projects from 2008. Price escalation of hydro power

projects from the year 2002 can reach between 70 and 80% for a

period of seven years. It is expected, however, that inflation costs

will come down as a result of the current credit crisis.

• The diagrams presented were found suitable for a close estimation

of costs of E&M equipment per unit under a comparison of costs

from current hydro power projects. These diagram s have been

developed to provide a quick way to determine costs of electrical

and mechanical equipment (at pre-investment, due diligence study,

pre-feasibility and feasibility level) based on main parameters such

as head, design discharge and power.

• The value of the cost curves in the diagrams needs to be updated

each year.

• The original data set was composed of 89 plotting positions, but

eight points have unsuitable locations in the diagrams, particular-

ly the Francis turbine and pump-turbine charts. Such points were

not used. As an example, the cost of E&M equipment for La Muela

II pumped storage project in Spain – according to the information

reported in July 2008 – was US$55M for four units of 213MW

each, a head of 520m and a unit discharge of 48m

3

/sec. It will mean

a cost per unit of around US$14M. It is considered that some fac-

tors influence the cost estimation of these units, leading to an under-

estimated contract cost value. Seven points of projects awarded in

the last two years had similar underestimated contract cost. The

causes for these underestimated values were not found.

• An improvement in data available could be performed taking into

account the type of turbine axis. This can have a significant impact

on E&M equipment costs.

Cesar Adolfo Alvarado-Ancieta, Civil Engineer, Dipl.-

Ing., M. Sc., Hydropower, Dams, Hydraulic Engineering

Email: cesalv@yahoo.com

References

[1] Gordon, J.L. and Penman, A.C. (1979). Quick estimating techniques for

small hydro potential. Water Power & Dam Construction, V. 31, p. 46-51.

[2] Gordon, J.L. (1981). Estimating hydro stations costs. Water Power &

Dam Construction, V. 33, p. 31-33.

[3] Gordon, J.L. (1983). Hydropower costs estimates. Water Power & Dam

Construction, V. 35, p. 30-37.

[4] Gordon, J.L. and Noel, C.R. (1986). The economic limits of small and

low-head hydro. Water Power & Dam Constr uction, V. 38, p. 23-26.

[5] Nachtnebel, H.P. (1981): Bewertung der Kleinwasserkraftwerke, in:

Österreichische Wasserwirtschaft, Jahrgang 33, Heft 11/12.

[6] Aggidis, G.A. - Luchinskaya, E. - Rothschild, R. - Howard, D.C. (2008).

Estimating the costs of small-scale hydropower for the progressing of world

hydro development. Hydro 2008, Ljubljana, Slovenia - The International

Journal on Hydropower & Dams.

IWP& DC

0

.1 MW

1 MW

0

.1 MW

20 Mio US$

10 100 10001

1 MW

Q

[m

3

/

s]

1

0 MW

10 MW

1

00 MW

100 MW

1

000 MW

1000 MW

3

0 M$, 74 MW

60 M$, 130 MW

30

40

50

60

7

0

The cost includes turbines, governors,

valves, cooling and drainage water systems,

cranes, workshop, generators, transformers,

earthing system, control equipment,

telecommunications systems and auxiliary systems.

H [m]

Cost of electrical and mechanical

equipment in a powerhouse per unit

with a Francis Pump Turbine

(data series 2002-2008) Valid for 2009

6

6 M$, 380 MW

48.31 M$, 250 MW

5

4 M$, 240 MW

1000100101

Figure 5: Costs of E&M equipment in powerhouses per unit with Francis pump-turbine

26 FEBRUARY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

ENVIRONMENT

1999 and officially launched the certification programme in January

2000. The institute received its first application for certification in

May 2000. As of 1 January 2009, the institute has certified 37 pro-

jects (103 d ams) in 22 states from Maine to Alaska with a com-

bined installed capacity of 2135.58MW (see certification list).

Through its certification programme, the institute serves a broad

constituency with a variety of stakeholders including environmen-

talists, consumers, renewables and green energy labeling groups,

power marketers, and the hydro power industry.

The institute serves these various interests by providing a nation-

al independent and objective mechanism fo r identifying hydro

power facilities that are low impact relative to other hydro facili-

ties. By providing a voluntary certification programme centered on

environmental criteria, consumers are able to choose low impact

hydro power over other hydro when purchasing electricity.

There are also non-commercial groups that are identifying or

labeling energy products as green or environmentally preferable.

These groups generally set standards for the amount and type of

renewable energy th at can achieve their label, and these energy

products are then available for customers in competitive markets.

The groups typically look at a range of renewable energy products

such as solar, wind, and biomass. However hydro power, due to its

environmental effects, can prove difficult to include in the renew-

ables mix. In addition, due to the complex statutory and regulato-

ry scheme surrounding hydro power generation, addressing hydro

effects requires some specialised knowledge and focus.

The institute provides this expertise through its rigorous pro-

gramme focused solely on hydro power and provides these groups

with the ability to uti l i s e the certificatio n programme , backed by

the strength and credibility of a governing board well-versed in

hydro power issues.

Hydro power proje ct owners who want to gain a competitive

edge in the new energy markets now have a way of obtaining recog-

nition for their well-op erated and well-sited facilities by getting

them certified as low impact by the institute. Moreover, the indus-

try can obtain this certification regardless of the size of its facility

– as long as it meets the criteria, the facility will be identified as low

impact.

Back in March 2002, I wrote an article on the institute for

IWP&DC when it was the ‘new kid on the block’. I didn’t kno w

much about them, but after interviewing their then executive direc-

tor, Lydia Grimm, I walked away from the interview very impressed

with what they had done to create a unique organisation.

At the time I wondered if it could survive without a robust green

market and the support and interest of the hydro power industry.

Well, it did survive and one of the reasons I believe it has been so

successful is the efforts of its volunteer governing board. I caught

up with three veteran board members who have been with the

T

HE Low Impact Hydropowe r Institute (LIHI ) was

establ ished in the US as an independent non-pr ofit

corporati on dedicated to providing a voluntary certifi-

cation programme f or identifying low impact hydro

power. The concept for t he institute developed from the efforts of

American Rivers (a national river conservation organization) and

Green Mountain Energy (a marketer of green electricity) to devel-

op appropriate mechan isms for identifying environmentally

prefer able hydro power for use by consumers in th e emerging

competitive electricity markets.

The institute’s governing board met for the first time in November

The Low Impact Hydropower Institute will celebrate its tenth anniversary in 2009. Here,

Executive Director Fred Ayer interviews three members of LIHI’s governing board and

asks these green hydro pioneers to take a look back at the institute’s ten-year record

Green hydro pioneers:

ten years on

LIHI: who’s who?

Richard Roos-Collins (LIHI Chair) has served

as the Director of Legal Services at the

Natural Heritage Institute in San Francisco

since 1991. He is a director of the Natural

Heritage Institute, a public interest law firm in

San Francisco, where he represents both

public and private clients in matters to

improve the management of water, other

natural resources and energy, and

emphasises settlements to restore

environmental quality consistent with

economic growth.

Steve Malloch, (LIHI Treasurer) works on

Western water resources issues for the

National Wildlife Federation from Seattle. He

has been involved with hydro power since the

mid-1990’s as a consultant and lobbyist for

conservation organisations on federal

legislation. As a consultant to American

Rivers, he helped shape the strategy and

organisation for the Low Impact Hydropower

Institute (LIHI) and continues to serve on its

board of directors.

Sam Swanson (LIHI Secretary) is Director of

Renewable Energy Technology and Market

Analysis at the Pace Law School Energy and

Climate Center. His work aims to reduce the

barriers to the deployment of sustainable

renewable energy technology and to encourage

the growth of voluntary clean energy markets.

Fred Ayer is the Executive Director of the Low

Impact Hydropower Institute and can be

reached at fayer@lowimpacthydro.or g

organisation since 1999. I wanted to ask them a few questions and

get their sense on how successful the institute has been since its cre-

ation and their hopes for the future.

Ayer: As one of the founders of LIHI, you were very involved in

creating the organization. Has it turned out the way you had orig-

inally envisioned? If not, do you have any sense why?

Roos-Collins: Foolish plans of mice and men, right? LIHI has large-

ly met my original expectations. Let me explain what th ey were.

The founders intended our programme to enhance environmental

quality at existing hydro power projects by encouraging licensees

to exceed the regulatory min imums which the Fede ral Energy

R

egulatory Commission ( FERC) would otherwise impose in

licences. Specifically, our criteria ask wh eth er a given project fol-

lows the recommendations for flow releases, fish passage, and other

environme ntal enhancements as proposed by resource agencies

under Federal Power Act section 10(j).

In 1999, FERC frequently rejected such recommendations on its

own initiative, and licensees rarely reached settlements with other

stakeholders. Our programme was intended to help chan ge tha t

reality. We beli eved that FERC was more likely to incorporate

enhancement measures into a projec t licence if the licensee affir -

matively said that it accepted them as a business decision. Why

would a licensee do that? We expected that our certification would

increase project revenue – indeed, more than the cost of accepting

such measures – since many electricity customers would pay a pre-

mium for such green power.

So, how has the world turned? Today, just nine years later, most

licences are based on settlements between licensees, resource agen-

cies, and other stakeholders. Such settlements typically incorporate

agency recommendations under Federal Power Act section 10(j).

That positive trend mostly reflects a widespread recognition in this

regulatory community of the comparative benefits of settlement

versus litigation in relicensing proceeding. For some licensees, our

certification pro gramme provided the extra benef it necessary for

them to accept that new approach.

Malloch: When we started this e ffort more than ten y ears ago it

looked like we would have robust retail competition for electricity.

Deregulation and breaking the utilities up was a foregone conclu-

sion. We saw an opportunity to differentiate power in a way that

furthered our goals of improving river health. We wanted to make

certified hydro power like organic food – good for you and good

for the environment.

In addition, we wanted to provide an incentive for accepting pos-

itive pu blic benefit and environmental health term s in the FERC

relicensing process and support settlement.

We got up and running, with our first few certifications under-

way, when the electricity system went crazy, undercutting our strat-

egy. Deregulation and retail competition went out. But it turned out

that hydro power owners st ill wa nted recogni tion for the good

things they were doing, espe cially as a result of relicensin g. That

got us through a few lean years.

Now there is increasing institutional and corporate demand for

green power as part of a drive for corporate responsibility and sus-

tainability. That is driving many hydro power owners to seek cer-

tification – some are getting real premiums by selling certified power

to institutional buyers. There is also a growing interest in including

certified hydro power as part of renewable portfolio st andards

(RPS).

LIHI’s story is similar to many startups. The initial market target

turned out to be wrong, for reasons we could not foresee. But by

staying alive and continuing to work at developing a niche, we final-

ly found a real opening. From here, we think we can grow the busi-

ness, and continue to seek improvements to the way hydro power

projects are operated.

Swanson: I envisioned that the creation of LIHI would quickly iden-

tify t he hydro power faciliti es that meet minimum standards for

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM FEBRUARY 2009 27

their environmental quality and the impa cts they have on key

ecosystem attributes. I envisioned that this certification programme

would help the public understand that some hydro power has rel-

atively few adverse impacts and that some pose very significant

problems. I think LIHI is fulfilling this vision but it is taking longer

to accomplish this than I anticipated at the start. With LIHI we

wanted to make sure that hydro power marketed as green power

or clean power really was power generated by hydro power facili-

ties that did not cause serious environmental problems.

When we started there was a disturbing trend by policy makers

toward distinguishing low impact hydro power on the basis of the

size of the unit, not the specific impacts on local fisheries or water

quality or other attributes that relate to local conditions. LIHI has

h

elped people understand that not all small hydro power facilities

are benign and that not all large hydro power facilities produce

severe impacts. Nevertheless I find many people continue to assume

that small hydro facilities pose few risks and that large ones are

problematic.

Ayer: How much has the climate change debate altered the wa y

environmental organisations think about hydro power’s role in the

future?

Roos-Coll ins: A sea change is underway. For many decades, a

debate has occurred about whether hydro power is renewable.

Licensees argued that their projects use a renewable source, water,

to generate power, while environmental groups focused on the sig-

nificant impairments of renewable resources, the fish and wildlife

species which depend on natural flows. In my view, that debate is

stale. It focuses on existing projects. That ignore s the imperati ve

that we develop new renewable power to replace existing coal and

other t hermal generation, in order to lessen the rate of cl imate

change and increase energy independence. LIHI now certifies retro-

fits of non-hydro power dams to add such renewable capacity. That

reflects the principle that new renewable power must be designed,

built, and operated to protect the local aquatic ecosystem, not just

the global commons.

Malloch: There has always been a tension between the notions that

‘dams are bad’ and th at ‘hydro power is good’ in both environ-

mental organizations and the broader population. Climate change

heightens that tension, but I have not seen a major shift in thinking

about hydro power.

In most organisations the thinking is that we need new non-hydro

power renewables. Hydro power is seen as a mature resource, with

little new generation potential from new traditional projects because

the best sites are used or off limits. However, there is interest in

retrofitting existing non-power dams with generators and uncon-

ventional hydro power. Other resources, especially wind, solar and

non-food based biofuels are seen as having the most promise.

When we get a carbon-constrained economy, and have to run an

electricity grid with more intermittent generation sources, we might

see renewed appreciation of hydro power.

Swanson: The climate change crisis has had the effect of elevating

the concern about power sources that contribute to climate change,

and consequently reducing the priority to other ecosystem impacts.

I endor se this focus because the inatten tion given to the climate

crisis for the las t two decades has reduced the time available and

increased the difficulty of addressing this.

Nevertheless, I believe the ecosystem impacts that LIHI focuses

on in its certification programme remain important and are crucial

to long term efforts to find sustainable paths to meet our local and

global energy needs. The LIHI plays an important role in offering

science-based criteria for identifying and mitigating the important

impacts caused by hydro power construction and operati on. All

energy production sources pose varying environmental risks. LIHI

plays an important role in encouraging facility owners to take steps

to reduce impacts that are not addressed in the hydro power licens-

ing process.

ENVIRONMENT

28 FEBRUARY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

ENVIRONMENT

Ayer: Some have suggested that the LIHI certification programme

should be used as the eligibility metric of any national renewable

portfolio standard (RPS) that Congress passes. What do you think?

Roos-C ollins: Yes, as a permissive eligibility metric for hydro

power. Let me start with the negative. It might be inappropriate

for RPS to use our certifica t ion as the sole and mandatory metric,

since that would delegate public policy to t he control of a non-

profit corporatio n. By contrast, using our ce rtification as a per-

missiv e metric would make common sense. As the only

certification programme for hydro power in the US , we have a

ten-year track record of fairly applying our criteria. We actively

solicit, consider, and respond to pub lic commen ts on each appli-

cation. Our decisions are public rec ords. Our c ertifications h ave

resulted in new revenues and other substantial business benefits

for project owners, who uniformly seek renewal at the expiration

of origina l certifications.

In sum, our programme provides a public service – distinguish-

ing superior performance in environmental enhancement – that may

be inco rporated into RPS or other public policie s designed to

Low Impact Certification list, January 1, 2009

Project Certificate Number, Name, Owner State Size Certification Date

LIHI Certificate # 00001 Stagecoach (Upper Yampa Water Conservancy District) CO 0.8 MW (1 dam) March 27, 2001

LIHI Certificate # 00002 Island Park (Fall River Rural Electric Coop) ID 4.8 MW (1 dam) June 7, 2001

LIHI Certificate # 00003 Putnam (Putnam Hydropower) CT 0.575 MW (1 dam) April 10, 2002

L

IHI Certificate # 00004 Falls Creek (Falls Creek Hydropower ) OR 4.3 MW (1 dam) June 3, 2002

L

IHI Certificate # 00005 Skagit River (Seattle City Light) WA 690 MW (3 dams) May 15, 2003

LIHI Certificate # 00006 Black Creek (Black Creek Hydro Inc.) WA 3.7 MW (1 dam) April 10, 2003

LIHI Certificate # 00007 Beaver River (Reliant Energy) NY 44.8 MW (8 dams) July 16, 2003

LIHI Certificate # 00008 Nisqually (City of Tacoma) WA 114 MW (2 dams) April 15, 2003

LIHI Certificate # 00009 Strawberry Creek (Lost Valley Energy) WY 1.5 MW (1 dam) October 27, 2003

L

IHI Certificate # 00010 Worumbo (Miller Hydro Group) ME 19.4 MW (1 dam) Februar y 19, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 00011 Pawtucket (Pawtucket Hydro LLC) RI 1.3 MW (1 dam) April 23, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 00012 Tallassee Shoals (Fall Line Hydro Company LLC) GA 2.3 MW (1 dam) April 23, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 000013 Hoosic River (Brascan) NY 18.5 MW (2 dams July 9, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 000014 Raquette River (Brascan) NY 160.3 MW (14 dams) July 9, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 000015 Bowersock (Bowersock Mills and Power Company) KS 2.5 MW (1 dam) July 9, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 000016 Winooski One (Winooski One Partnership) VT 7.4 MW (1 dam) July 29, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 000017 Summersville (Gauley River Partners) WV 80 MW (1 dam) November 10, 2004

LIHI Certificate # 000018 Tapoco (Alcoa Power Generating , Inc.) TN and NC 326 MW (4 dams) July 25, 2005

LIHI Certificate # 000019 West Springfield (A&D Hydro , Inc.) MA 1.4 MW (1 dam) August 29, 2005

LIHI Certificate # 000020 Salmon River (Br ookfield Power Corporation) NY 36.25 MW (2 dams) November 14, 2005

LIHI Certificate # 000021 Buffalo River (Fall River Rural Electric Coop) ID .25 MW (2 dams) April 27, 2006

LIHI Certificate # 000022 Black Bear Lake (Alaska Power & Telephone) AK 4 .5 MW (1 dam) May 19, 2006

LIHI Certificate # 000023 Raystown (Allegheny Electric Cooperative) PA 21 MW (1 dam) August 11, 2006

LIHI Certificate # 000024 Mother Ann Lee (Lock 7 Partners LLC) KY 2.04 MW (1 dam) October 11 , 2006

LIHI Certificate # 000025 Pelton Round Butte (Portland General Electric) OR 366.8 MW (3 dams) October 30, 2006

LIHI Certificate # 000026 Goat Lake (Alaska Power & Telephone) AK 4 MW (1 dam) October 23, 2006

LIHI Certificate # 000027 West Branch St. Regis (Brookfield Power) NY 6.8MW (2 dams) September 14, 2005

LIHI Certificate # 000028 Champlain Spinners (Champlain Spinners Hydropower Co.) NY 2.2 MW (1 dam) August 31, 2007

LIHI Certificate # 000029 Jordanelle Dam (Central Utah Water Conservancy District.) UT 12.0 MW (1 dam) June 10, 2007

LIHI Certificate #000030 Lake Chelan (PUD#1 of Chelan County) WA 48.0 MW (1 dam) September 26, 2007

LIHI Certificate #000031 Boulder Creek (S & K Holding Company) MT 350 kW (1 dam) October 24, 2007

LIHI Certificate #000032 Newton Falls (Brookfield Power, New York) NY 2.22 MW (2 dam) November 1, 2007

LIHI Certificate #000033 Willamette Falls (Portland General Electric) OR 15.18 MW (1 dam) November 2, 2007

LIHI Certificate #000034 Black River (Brookfield Power, New York) NY 37.6 MW (6 dams) December 7, 2007

LIHI Certificate #000035 Oswego River (Brookfield Power, New York) NY 25.5 MW (4 dams) December 7, 2007

LIHI Certificate #000036 Tieton River (Tieton Hydro LLC) WA 14 MW (1 dam) March 3, 2008

LIHI Certificate #000037 Kingsley Dam (CNPPID) NE 67.5 MW (26 dams) May 22, 2008

TOTAL 2,135.58 MW (103 dams)

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM FEBRUARY 2009 27

encourage renewable power development. Similarly, certification

programmes for other goods are administered by private corpora-

tions, such as Green-E (other sources of renewable power), Forestry

Stewardsh ip Coun cil (lumber p roducts), or U nderwriters’

Laboratories (electrical and other residential goods).

Swanson: I believe that the underlying crit eria that support LIHI

certifica tion should be used in any RPS. Whether certification

administered by a non-government organization can or should be

used for qualifying resources for a federal or state regulated policy

is a question that has to be addressed if LIHI certification is to be

considered. More important is the current focus of LIHI certifica-

tion on existing hydro power facilities. RPS policy focuses on addi-

t

ions to the supply of qu alifying renewable energy generated

electricity. This diminishes the role LIHI certification could play in

the RPS programme.

Ayer: If you could go back to 1999 during the days of creating

LIHI, what would you do differently?

Roos-Collins: Water under the bridge. Let’s talk about the future!

Malloch: Hindsight being what it is, I would have put more atten-

tion towards developing demand for certified power from the ulti-

mate customers rather than just on the h y d ro power owners. We

might have seen that retail competition was difficult and focused

instead on large commercial and institutional power users. I would

have also worked harder at our revenue model. Initially we relied

on foundation grants and certifications. Now modest annual fees

allow us to do more marketing and to get the word out about LIHI,

which benefits certification holders.

Swanson: I would have liked to see LIHI commit resources to edu-

cating the public about river systems and the way hydro power

facilities pose threats to river systems. Resource limitations, includ-

ing the time of the LIHI executive director and board of directors,

were barriers to addressing that while also focusing on administer-

ing the new certification process. I hope the LIHI will succeed in

connecting with the communities around hydro facilities, pointing

out what is working and what continues to threaten the health of

America’s rivers and streams.

Ayer: LIHI does not accept certification applications for projects

outside the US. Can you see a day when the LIHI certification pro-

gramme might be extended to Canada or South America?

Roos-Coll ins: Unlikely in the next few years. Our programme

reflec ts the regulatory and other legal requirements for hydro

power in the US. Essentially, we ask: does a project exceed the min-

imum requirements of the Federal Power Act? We would have to

start from scratch in Canada or South America, which of course

have very different legal requ irements. Plus, the LIHI staff and

board will have our hands full keeping up with certification

requ ests from domestic projects if federal RP S legislation recog-

nises our programme.

One possibility is redesigning the program to state objective cri-

teria, such as the degree of control and alteration of natural flows.

In that form, it would apply anywhere. The fou nders considered

and rejected that approach in 1999. Even if objective on paper, such

criteria would require the LIHI board to use substantial judgment

and discretion in considering the facts of a given application. Since

seeking our certification is still vol untary, why would a project

owner trust us to apply criteria where a rational answer could be

yes or no?

Malloch: International certification is a direction we want to go. It

will take some work, becau se the licensing systems are differen t,

but we think that we can develop approaches that work indepen-

dent of the regulatory system.

Swanson: I hope that this happens. It is particularly important to

have a LIHI certification process applied in Canada where there are

so many large existing and yet untapped hydro power resources. I

live in Vermont where we currently depend on hydro power from

Quebec, Canada for a large proportion of our electricity supply. It

is difficult to sort out the conflicting claims about the environmen-

t

al impacts of the hydro power imported from Canada. It would be

very helpful if there were an independent organisation in Canada,

like the LIHI providing certification of the hydro power imported

to the US.

Ayer: What is LIHI’s future? Where will it be in five years?

R

oos-Colli ns: Our future will be influenced by RPS and other

renewable power policy, which will chang e more in the next five

years than the past 20. Having said that, I hope that LIHI will make

two changes on our own initiative. We should offer different levels

of certification, such as basic to exceptional. This would encourage

owners to go the extra mile in protecting the local ecosystem.

Second, we should expand our programme to include new pro-

jects, both inland and marine. Our programme today reaches exist-

ing projects, including retrofits. As I said above, new generation –

unlike fine-tuning existing generation – will be necessary to miti-

gate climate change and contribute to energy independence. LIHI

should be part of that solution.

Malloch: We see LIHI continuing to grow rapidly as the demand

for green power grows among consumers. There are better hydro

power projects that should be rewarded for their efforts. There are

also projects that need to improve their environmental performance.

We serve a real role in helping to distinguish between the two. There

is also a role for LIHI in RPS programmes for the same reason.

Most RPS systems use a size limit for hydro power, but small hydro

is no t necessarily better hydro. We want R PS systems to include

only better hydro.

Swanson: My hope is that our nascent efforts to market LIHI cer-

tification will gain a strong foothold among environmental educa-

tion organisations, their members, and the million s of other

Americans who t reasure our environment and are committed to

wrestling with the difficult trade-offs involved in meeting our energy

needs in a way that is sustainable in the long term. We are making

progress but I think we still have a long way to go.

Ayer: My personal goals for the institute have not changed much,

and I don’t have much to add to what Richard, Steve, and Sam have

said. However, I do have some updated goals for the next five years:

• Continue to be recognised as the gold standard for certifying low

impact hydro power.

• Certify between 60 and 70 hydro projects as low impact and have

those projects be recognised and compensated for that status.

• Continue to be a credible and knowledgeable vo ice. To help

the gr een market evolve to the point that state and federal

governments go beyond arbitrary, and relatively meaningless size

and date of construct ion criteria, for determining eligibility

of existing hydro projects in procurement programmes and RPS

eligibility standards.

If you’d like further information please contact Fred Ayer

at: fayer@lowimpacthydro.org or visit the LIHI website at

www.lowimpacthydro.org

Previous articles on the LIHI are available online at

www.waterpowermagazine.com. Simply enter the

keyword LIHI in our archive for a full listing

ENVIRONMENT

IWP& DC

30 FEBRUARY 2009 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

tual removal of four dams on the Klamath River. Sceptics point out

that the Klamath River Agreement is really an accord to keep the

dams until 2020, to study the feasibility of removal, and for the state

and utility to split the costs if the dams are eventually removed [2].

However, even sceptics would admit th at the ag reement sets the

direction [3]. The eventual removal of the Klamath dams would rep-

resent an important victory for dam removal activists, especially in

a state with ambitious goals in renewable energy generation.

The US has approximately 79,000 significant dams [4] and prob-

ably has the most experience in removing them. Over the twentieth

C

OMPLETION of the 2080MW Hoo ver Dam on the

Colorado River in 1935 was a significant moment in the

history of dam building in the US. Some say that it was a

tipping point that fired the imagination of dam builders

and led to a surge of dam building across America [1]. However

smaller scale hydroelect ric dams were being built all over the US

from the turn of the century. What building the Hoover Dam really

fired was the confidence of d am-builders: if the Colorado River

could be tamed, then they could dam any river.

However not everyone considered the dams to be progress, and

over the decades movements to prevent new dams being built, and

to remove old ones, have grown stronger.

Recently, works have commenced to prepare for removal of the

Elwha and Glines Canyon dams in Washington State. These dams

are relatively tall: the Glines Canyon dam is 64m high, but their

power output is small, with a combined total of 28MW. What really

sets them apart however is the cost of their removal. A price tag of

over US$300M sets a new high-water mark in the price that the

nation is prepared to pay to restore it’s rivers.

So does this represent a tipping point in the opposite direction –

towards removal of dams?

Another example, this time from California, might suggest that a

tipping point has been reached. In November 2008 an agreement

was signed between owners and protagonists concerning the even-

An alternative to refurbishment of dams is the retirement and removal of structures which

have reached the end of their life cycle. Over 450 dams have been removed in the US alone,

with some of the largest being hydro dams. So what has been learnt? Here, Kevin Oldham

draws from recent US case histories of hydro dam removals, exploring trends across three

critical interlinked areas: costs; sediment management; and dam removal methodology

Table 1: Dam removal in the US

Year of removal Number Average Maximum

removed height (m) height (m)

1920-1950 16 4 7.9

1951-1980 31 7.5 17.1

1981-1990 92 7.1 38.1

1991-2000 137 6.2 48.8

2001-2008 154 3.5 18.3

Note: Includes only dams for which height and year of removal are known

Decommissioning dams –

costs and trends

Demolition of the Marmot dam on the Sandy

River, part of the Bull Run hydro pr oject.

Courtesy of Portland General Electric