Ware C. Information Visualization: Perception for Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6. Where appropriate hardware is available, both structure-from-motion (by rotating the

surface) and stereoscopic viewing will enhance the user’s understanding of 3D shape.

These may be especially useful when one textured transparent surface overlays another.

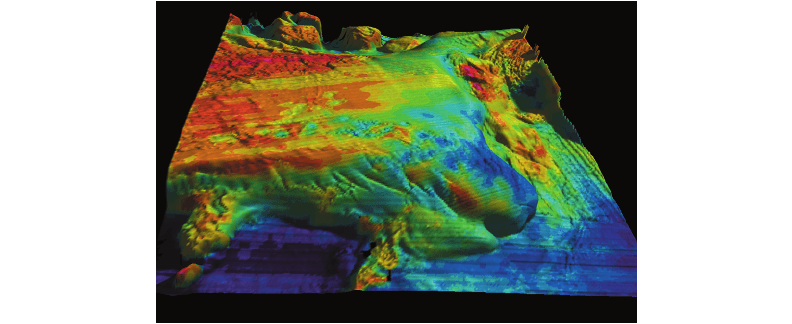

Bivariate Maps: Lighting and Surface Color

In many cases, it is desirable to represent more than one continuous variable over a plane. This

representation is called a bivariate or multivariate map. From the ecological optics perspective

discussed in Chapter 1, the obvious bivariate map solution is to represent one of the variables

as a shaded surface and the other as color coding on that surface. A third variable might use

variations in the surface texture. These are the patterns we have evolved to perceive. An example

is given in Figure 7.26, where one variable is a height map of the ocean floor and the surface

color represents sonar backscatter strength. In this case, the thing being visualized is actually a

physical 3D surface. However, the technique also works when both variables are abstract. For

example, a radiation field can be expressed as a shaded height map and a temperature field can

be represented by the surface color.

If this colored and shaded surface technique is used, some obvious tradeoffs must be

observed. Since luminance is used to represent shape-from-shading by artificially illuminating the

surface, we should not use luminance (at least not much) in coloring the surface. Therefore, the

surface coloring must be done mainly using the chromatic opponent channels discussed in

Chapter 4. But because of the inability of color to carry high–spatial frequency information, only

rather gradual changes in color can be perceived. Therefore, in designing a multivariate surface

display, rapidly changing information should always be mapped to luminance. For a more

254 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

Figure 7.26 A bivariate map showing part of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (Mayer et al., 1997).

One variable shows angular response of sonar backscatter, color-coded and draped on the depth

information given through shape-from-shading. Courtesy of Larry Mayer.

ARE7 1/20/04 5:57 PM Page 254

detailed discussion of these spatial tradeoffs, see Robertson and O’Callaghan (1988), Rogowitz

and Treinish (1996), and Chapter 4 of this book.

A similar set of constraints applies to the use of visual texture. Normally it is advisable to

use luminance contrast in displaying texture, but this will also tend to interfere with shape-from-

shading information. Thus, if we use texture to convey information, we have less available visual

bandwidth to express surface shape and surface color. We can gain a relatively clear and easily

interpreted trivariate map, but only so long as we do not need to express a great deal of detail.

Using color, texture, and shape-from-shading to display different continuous variables does not

increase the total amount of information that can be displayed per unit area, but it does allow

multiple map variables to be independently perceived.

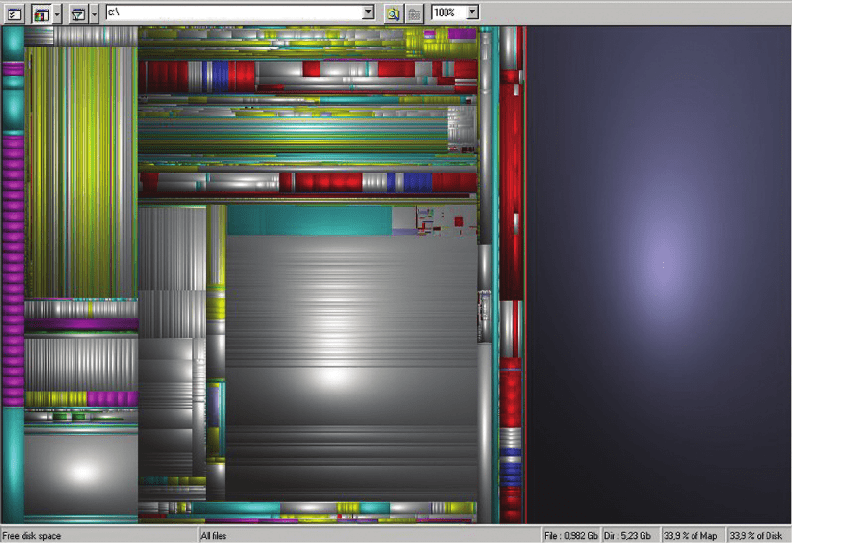

Cushion Maps

The treemap visualization technique was introduced in Chapter 6 and illustrated in Figure

6.36 (Johnson and Shneiderman, 1991). As discussed, a problem with treemaps is that they

do not convey tree structure well, although they are extremely good at showing the sizes and

groupings of the leaf nodes. An interesting solution devised by van Wijk and van de Wetering

(1999) makes use of shading. They applied a hierarchical shading model to the treemap so

that areas representing large branches are given an overall shading. Regions representing

smaller branches are given their own shading within the overall shading. This is repeated down

to the leaf nodes, which have the smallest scale shading. The illustration shown in Figure

7.27 shows a computer file system. As can be seen, the hierarchical structure of the system is

quite clear.

Integration

In this chapter, we have seen a number of ways in which different spatial variables interact to

help us recognize objects, their structures, and their surfaces. However, there has been no dis-

cussion of how the brain organizes these different kinds of information. What is the method by

which the shape, color, size, texture, structure, and other attributes of an object are stored and

indexed? Unfortunately, this is still a largely open question. Only some highly speculative theo-

ries exist.

One suggestion is the theoretical concept of the object file, introduced by Kahneman and

Henik (1981) to account for human perceptual organization. An object file is a temporary cog-

nitive structure that stores or indexes all aspects of an object: its color, size, orientation, texture,

and even its name and other semantic links (Kahneman et al., 1992). An object file can be thought

of as a cognitive data structure that maintains links to all the perceived attributes of an object.

An object file allows us to keep track of objects in the visual field, and from one fixation to the

Visual Objects and Data Objects 255

ARE7 1/20/04 5:57 PM Page 255

next when they temporarily disappear behind other objects. Work by Pylyshyn and Storm (1988)

and Yantis (1992) suggests that only a small number of visual objects, somewhere between two

and four, can be maintained simultaneously in this way. Because of this, the display designer

should drastically restrict the number of complex objects that are required simultaneously for

any complex decision-making task.

Because both linguistic and visual information is included in the object file, it explains a

number of well known psychological effects. One effect is that almost any information about an

object, either visual or verbal, can be used to prime for that object. If there were a strong sepa-

ration between visual and verbal information, we would not expect a verbal priming cue, for

example, the word bark, to make it easier to identify a picture of a dog. But in fact, verbal

priming does improve object recognition, at least under certain circumstances.

However, as discussed earlier in this chapter, there are also many priming effects that are

strongest within a sensory modality; this is part of the evidence for separate verbal and visual

processing centers. The concept of the object data structure also accounts for interference effects.

256 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

Figure 7.27 The cushion map is a variation on a treemap that uses shape-from-shading information to reveal

hierarchical structure. Courtesy of Jack van Wijke.

ARE7 1/20/04 5:57 PM Page 256

In the Stroop effect, subjects read a list of color words such as red, yellow, green and blue (Stroop,

1935). If the words themselves are printed with colored inks and the colors do not match the

word meanings—for example, the word blue is colored red—people read more slowly. This shows

that visual and verbal information must be integrated at some level, perhaps in something like

Kahneman and Henik’s object file.

Speculating further, the cognitive object file also provides an explanation of why object dis-

plays can be so effective. Essentially, the object display is the graphical analog of a cognitive

object file. However, the strong grouping afforded by an object display can be a double-edged

sword. A particular object display may suit one purpose but be counterproductive for another.

Object-based displays are likely to be most useful when the goal is to give an unequivocal message

about the relationship of certain data variables. For example, when the goal is to represent a

number of pieces of information related to a part of a chemical plant, the object display can be

clear and unambiguous. Conversely, when the goal is information discovery, the object display

may not be useful because it will be strongly biased toward a particular structure. Other, more

abstract representations will be better because they more readily afford multiple interpretations.

Chapter 9 offers more discussion of the relationship between verbal and visual information and

presents a number of rules for integrating the two kinds of information.

Conclusion

The notion of a visual object is central to our understanding of the higher levels of visual pro-

cessing. In a sense, the object can be thought of as the point at which the image becomes thought.

Objects are units of cognition as well as things that are recognized in the environment.

There is strong evidence to support both viewpoint-dependent recognition of objects and the

theory that the brain creates 3D structural models of objects. Therefore, in representing infor-

mation as objects, both kinds of perceptually stored information should be taken into account.

Even though data may be represented as a 3D structure, it is critical that this structure be laid

out in such a way that it presents a clear 2D image. Special attention should be paid to silhou-

ette information, and if objects are to be rapidly recognized, they should be presented in a famil-

iar orientation.

Visual processing of objects is very different from the massive processing of low-level

features described in Chapter 5. Only a very small number of complex visual objects, perhaps

only one or two, can be held in mind at any given time. This makes it difficult to find novel

patterns that are distributed over multiple objects. However, there is a kind of parallelism in

object perception. Although only one visual object may be processed at a time, all the features

of that object are processed together. This makes the object display the most powerful way of

grouping disparate data elements together. Such a strong grouping effect may not always be desir-

able; it may inhibit the perception of patterns that are distributed across multiple objects.

However, when strong visual integration is a requirement, the object display is likely to be the

best solution.

Visual Objects and Data Objects 257

ARE7 1/20/04 5:57 PM Page 257

Once we choose to represent visual objects in a data display, we encounter the problem of

what degree of abstraction or realism should be employed. There is a tradeoff between literal

realism, which leads to unequivocal object identification, and abstraction, which leads to more

general-purpose displays. Most interesting is the possibility that we can create a kind of hyper-

realism through our understanding of the mechanisms of perception. By using simplified light-

ing models and enhanced contours, together with carefully designed colors and textures, the

important information in our data may be brought out with optimal clarity.

258 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

ARE7 1/20/04 5:57 PM Page 258

CHAPTER 8

Space Perception and the

Display of Data in Space

259

We live in a three-dimensional world (actually, four dimensions if time is included). In the short

history of visualization research, most graphical display methods have required that data be

plotted on sheets of paper, but computers have evolved to the point that this is no longer neces-

sary. Now we can create the illusion of 3D space behind the monitor screen, changing over time

if we desire. The big question is why we should do this. There are clear advantages to conventional

2D techniques, such as the bar chart and the scatter plot. Designers already know how to draw

diagrams and represent data effectively in two dimensions, and the results can easily be included

in books and reports. Of course, one compelling reason for an interest in 3D space perception is

the explosive advance in 3D computer graphics. Because it is so inexpensive to display data in an

interactive 3D virtual space, people are doing it—often for the wrong reasons. It is inevitable that

there is now an abundance of ill conceived 3D design, just as the advent of desktop publishing

brought poor use of typography and the advent of cheap color brought ineffective and often garish

use of color. Through an understanding of space perception, we hope to reduce the amount of poor

3D design and clarify those instances in which 3D representation is really useful.

The first half of this chapter presents an overview of the different factors involved in the per-

ception of 3D space. The second half gives a task-based analysis of the ways in which different

kinds of spatial information are used in performing seven different tasks, ranging from tracing

paths in 3D networks to judging the morphology of surfaces to appreciating an aesthetic impres-

sion of spaciousness. The way we use spatial information differs greatly, depending on the task

at hand. Docking one object with another and trying to trace a path in a tangled web of virtual

wires require different ways of seeing.

Depth Cue Theory

The visual world provides many different sources of information about 3D space. These sources

are usually called depth cues, and a large body of research is related to the way the visual system

ARE8 1/20/04 5:05 PM Page 259

processes depth-cue information to provide an accurate perception of space. Following is a list

of the more important depth cues. They are divided into categories according to whether they

can be reproduced in a static picture (monocular static) or a moving picture (monocular dynamic)

or require two eyes (binocular).

Monocular Static (Pictorial):

•

Linear perspective

•

Texture gradient

•

Size gradient

•

Occlusion

•

Depth of focus

•

Cast shadows

•

Shape-from-shading

•

Depth-from-eye accommodation (this is nonpictorial)

Monocular Dynamic (Moving Picture):

•

Structure-from-motion (kinetic depth, motion parallax)

Binocular:

•

Eye convergence

•

Stereoscopic depth

Shape-from-shading information has already been discussed in Chapter 7. The other cues

are discussed in this chapter. More attention is devoted to stereoscopic depth perception than to

the other depth cues, not because it is the most important, but because it is relatively complex

and because it is difficult to use stereoscopic depth effectively.

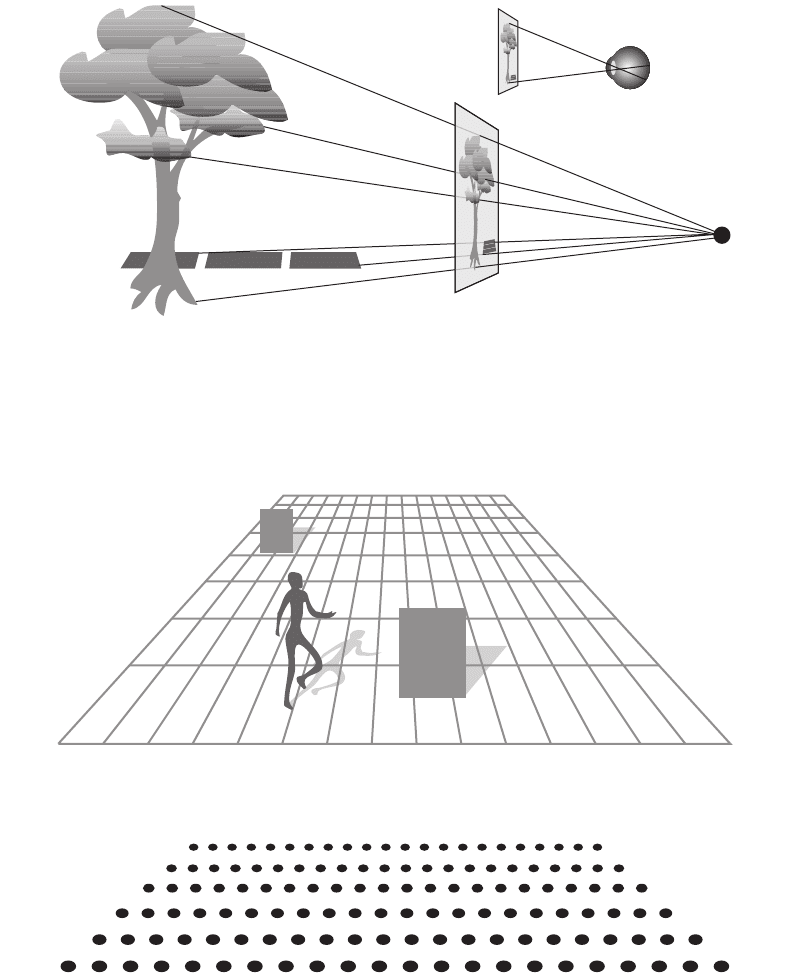

Perspective Cues

Figure 8.1 shows how perspective geometry can be described for a particular viewpoint and a

picture plane. The position of each feature on the picture plane is determined by extending a ray

from the viewpoint to that feature in the environment. If the resulting picture is subsequently

scaled up or down, the correct viewpoint is specified by similar triangles, as shown. If the eye is

placed at the specified point with respect to the picture, the result is a correct perspective view

of the scene. A number of the depth cues are direct results of the geometry of perspective. These

are illustrated in Figures 8.2 and 8.3.

260 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

ARE8 1/20/04 5:05 PM Page 260

Space Perception and the Display of Data in Space 261

Figure 8.1 The geometry of linear perspective is obtained by sending a ray from each point in the environment

through a picture plane to a single fixed point. Each point on the picture plane is colored according to the

light that emanates from the corresponding region of the environment. The result is that objects vary in

size on the picture plane in inverse proportion to their distance from the fixed point. If an image is

created according to this principle, the correct viewpoint is determined by similar triangles, as shown in

the upper right.

Figure 8.2 Perspective cues arising from perspective geometry include the convergence of lines and the fact that

more distant objects become smaller on the picture plane.

Figure 8.3 A texture gradient is produced when a uniformly textured surface is projected onto the picture plane.

ARE8 1/20/04 5:05 PM Page 261

•

Parallel lines converge to a single point.

•

Objects at a distance appear smaller on the picture plane than do nearby objects. Objects

of known size may have a very powerful role in determining the perceived size of adjacent

unknown objects. Thus, an image of a person placed in a picture of otherwise abstract

objects gives a scale to the entire scene.

•

Uniformly textured surfaces result in texture gradients in which the texture elements

become smaller with distance.

In the real world, we generally perceive the actual size of an object rather than the size at which

it appears on a picture plane (or on the retina). This phenomenon is called size constancy. The

degree to which size constancy is obtained is a useful measure of the relative effectiveness of

depth cues. However, when we perceive pictures of objects, we enter a kind of dual perception

mode. To some extent, we have a choice between accurately perceiving the size of the depicted

object as though it were in a 3D space and accurately perceiving the size of the object at the

picture plane (Hagen, 1974). The amount and effectiveness of the depth cues used will, to some

extent, make it easy to see in one mode or the other. The picture-plane sizes of objects in a very

sketchy schematic picture are easy to perceive. Conversely, the real 3D sizes of objects will be

more readily perceived with a highly realistic moving picture, although large errors will be made

in estimating picture-plane sizes.

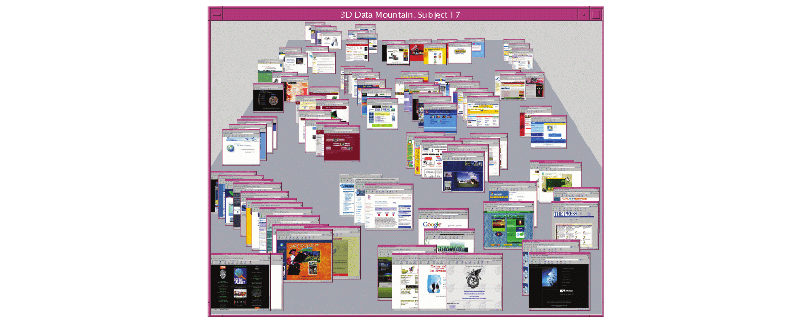

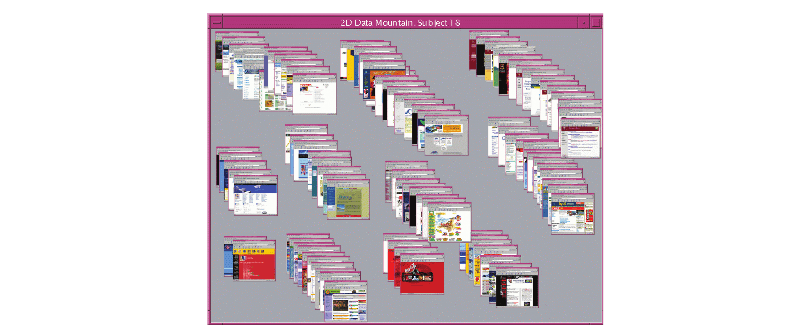

In terms of the total amount of information available from an information display, there is

little evidence that a perspective picture lets us see more than a nonperspective image. A study

by Cockburn and McKenzie showed that perspective cues added no advantage to a version of

the Data Mountain display of Robertson et al. (1998). The version shown in Figure 8.4(b) was

just as effective as the one in Figure 8.4(a). However, both of these versions make extensive use

of other depth cues (occlusion and height on the picture plane).

262 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

a

Figure 8.4 (a) Variations on Robertson et al.’s (1998) Data Mountain Display. Courtesy of Andy Cockburn.

ARE8 1/20/04 5:05 PM Page 262

Pictures Seen from the Wrong Viewpoint

It is obvious that most pictures are not viewed from their correct centers of perspective. In a

movie theater, only one person can occupy this optimal viewpoint (determined by the focal length

of the original camera and the scale of the final picture). When a picture is viewed from an incor-

rect viewpoint, the laws of geometry suggest that significant distortions should occur. Figure 8.5

illustrates this. If the mesh shown in Figure 8.5 is projected on a screen with a geometry based

on viewpoint (a), but it is actually viewed from position (b), it should be perceived to stretch

along the line of sight as shown (if the visual system were a simple geometry processor). However,

although people report seeing some distortion initially when looking at moving pictures from the

wrong viewpoint, they become unaware of the distortion after a few minutes. Kubovy (1986)

calls this the robustness of linear perspective. Apparently, the human visual system overrides some

aspects of perspective in constructing the 3D world that we perceive.

One of the mechanisms that can account for this lack of perceived distortion may be based

on a built-in perceptual assumption that objects in the world are rigid. Suppose that the mesh in

Figure 8.5 is smoothly rotated about a vertical axis, projected assuming viewpoint (a) but viewed

from point (b). It should appear as a nonrigid, elastic body. But perceptual processing is con-

strained by a rigidity assumption, and this causes us to see a stable, nonelastic three-dimensional

object.

Under extreme conditions, some distortion is still seen with off-axis viewing of moving pic-

tures. Hagen and Elliott (1976) showed that this residual distortion is reduced if the projective

geometry is made more parallel. This can be done by simulating long–focal length lenses, which

may be a useful technique if displays are intended for off-axis viewing.

Various technologies exist that can track a user’s head position with respect to a computer

screen and thereby estimate the position of the eye(s). With this information, a 3D scene can be

Space Perception and the Display of Data in Space 263

b

Figure 8.4 Continued (b) Same as part (a) but without perspective.

ARE8 1/20/04 5:05 PM Page 263