Walsh J.E. A Brief History of India

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

2

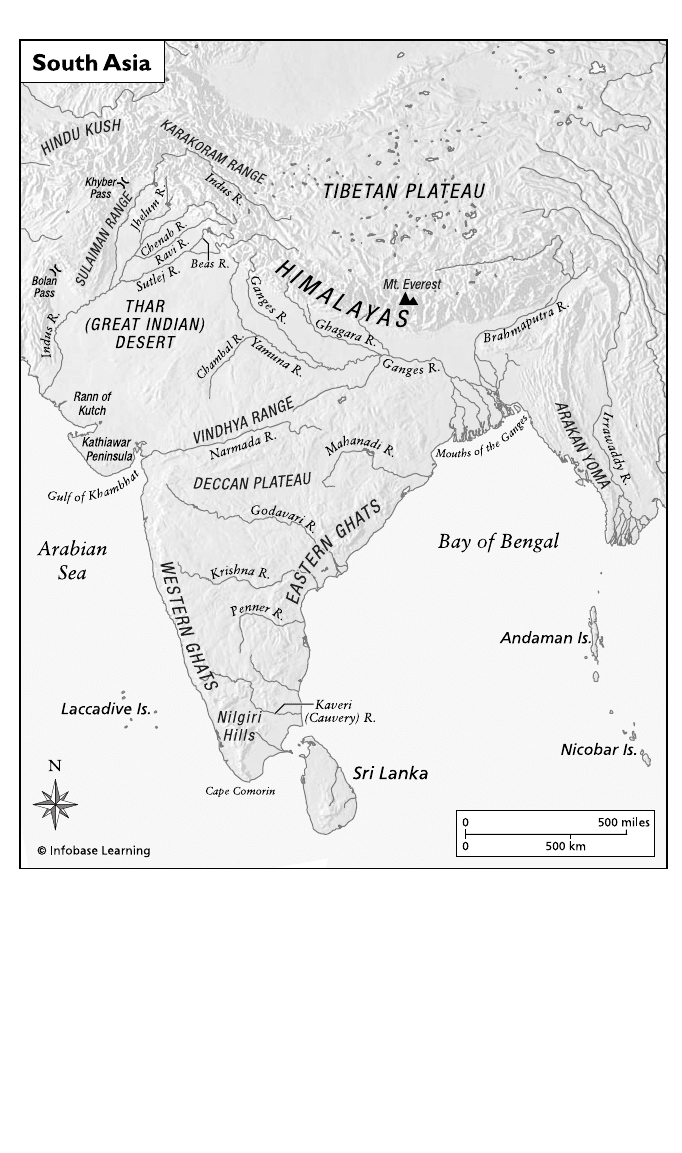

the tectonic plates that underlie the Earth’s crust slowly but inexorably

moved the island landmass known today as India away from its location

near what today is Australia and toward the Eurasian continent. When

the island and the Eurasian landmass fi nally collided, some 50 million

years ago, the impact thrust them upward, creating the mountains and

high plateaus that lie across India’s northwest—the Himalayas and the

high Tibetan Plateau. Over the next 50 million years, the Himalayas

001-334_BH India.indd 2 11/16/10 12:41 PM

3

LAND, CLIMATE, AND PREHISTORY

and the Tibetan Plateau rose to the heights they have today, with peaks,

such as Mount Everest, reaching almost nine kilometers (or slightly

more than fi ve and a half miles) in height.

The steep drop from these newly created mountains to the (once

island) plains caused rivers to fl ow swiftly down to the seas, cut-

ting deep channels through the plains and depositing the rich silt

and debris that created the alluvial soil of the Indo-Gangetic Plain,

the coastal plains of the Gujarat region, and the river deltas along

the eastern coastline. These same swift-fl owing rivers were unstable,

however, changing course dramatically over the millennia, disappear-

ing in one region and appearing in another. And the places where the

two landmasses collided became geologically unstable also. Today, the

Himalayas continue to rise at the rate of approximately one centime-

ter a year (approximately 10 kilometers every million years), and the

region remains particularly prone to earthquakes.

The subcontinent’s natural borders—mountains and oceans—pro-

tected it. Before modern times, land access to the region for traders,

immigrants, or invaders was possible only through passes in the north-

west ranges: the Bolan Pass leading from the Baluchistan region in mod-

ern Pakistan into Afghanistan and eastern Iran or the more northern

Khyber Pass or Swat Valley, leading into Afghanistan and Central Asia.

These were the great trading highways of the past, connecting India to

both the Near East and Central Asia. In the third millennium

B.C.E. these

routes linked the subcontinent’s earliest civilization with Mesopotamia;

later they were traveled by Alexander the Great (fourth century

B.C.E.);

still later by Buddhist monks, travelers and traders moving north to the

famous Silk Road to China, and in India’s medieval centuries by a range

of Muslim kings and armies. Throughout Indian history a wide range of

traders, migrants, and invaders moved through the harsh mountains and

plateau regions of the north down into the northern plains.

The seas to India’s east, west, and south also protected the subconti-

nent from casual migration or invasion. Here also there were early and

extensive trading contacts: The earliest evidence of trade was between

the Indus River delta on the west coast and the Mesopotamian trad-

ing world (ca. 2600–1900

B.C.E.). Later, during the Roman Empire,

an extensive trade linked the Roman Mediterranean world and both

coasts of India—and even extended further east, to Java, Sumatra, and

Bali. Arab traders took over many of these lucrative trading routes in

the seventh through ninth centuries, and beginning in the 15th cen-

tury European traders established themselves along the Indian coast.

But while the northwest land routes into India were frequently taken

001-334_BH India.indd 3 11/16/10 12:41 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

4

by armies of invasion or conquest, ocean trade only rarely led to inva-

sion—most notably with the Europeans in the late 18th century. And

although the British came by sea to conquer and rule India for almost

200 years, they never attempted a large-scale settlement of English

people on the subcontinent.

Land and Water

Internally the subcontinent is mostly fl at, particularly in the north. It

is cut in the north by two main river systems, both of which originate

in the Himalayas and fl ow in opposite directions to the sea. The Indus

River cuts through the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent

(modern-day Pakistan) and empties into the Arabian Sea; the many trib-

utaries of the Ganges River fl ow southeast coming together to empty into

the Bay of Bengal. Taken together, the region through which these rivers

fl ow is called the Indo-Gangetic (or North Indian) Plain. A third river,

the Narmada, fl ows from east to west into the Arabian Sea about halfway

down the subcontinent between the two low ranges of the Vindhya and

the Satpura Mountains. The Vindhya Range and the Narmada River are

geographical markers separating North and South India.

South of the Narmada is another ancient geological formation: the

high Deccan Plateau. The Deccan stretches a thousand miles to the

southern tip of India, spanning the width of southern India and much

of the peninsular part of the subcontinent. It begins in the Western

Ghats, steep hills that rise sharply from the narrow fl at coastline and

run, spinelike, down the subcontinent’s western edge. The plateau also

falls slightly in height from west to east, where it ends in a second set

of sharp (but less high) cliffl ike hills, the Eastern Ghats, running north

to south inward from the eastern coastline. As a result of the decreasing

west-to-east elevation of the Deccan Plateau and the peninsula region,

the major rivers of South India fl ow eastward, emptying into the Bay

of Bengal.

Historically the giant mountain ranges across India’s north acted

both as a barrier and a funnel, either keeping people out or channeling

them onto the North Indian plains. In some ways one might think of

the subcontinent as composed of layers: some of its earliest inhabitants

now living in the southernmost regions of the country, its more recent

migrants or invaders occupying the north. Particularly when compared

to the high northern mountain ranges, internal barriers to migration,

movement, or conquest were less severe in the interior of the subconti-

nent—allowing both the diffusion of cultural traditions throughout the

001-334_BH India.indd 4 11/16/10 12:41 PM

5

LAND, CLIMATE, AND PREHISTORY

entire subcontinent and the development of distinctive regional cul-

tures. The historian Bernard Cohn once suggested that migration routes

through India to the south created distinct areas of cultural diversity, as

those living along these routes were exposed to the multiple cultures of

successive invading or migrating peoples while more peripheral areas

showed a greater cultural simplicity. In any event, from as early as the

third century

B.C.E. powerful and energetic kings and their descendants

could sometimes unite all or most of the subcontinent under their rule.

Such empires were diffi cult to maintain, however, and their territories

often fell back quickly into regional or local hands.

Although the Indus, the Ganges, and the Brahmaputra (farther to the

east) all provide year-round water for the regions through which they

fl ow, most of the Indian subcontinent must depend for water on the sea-

sonal combination of wind and rain known as the southwest monsoon.

Beginning in June/July and continuing through September (depending

on the region), winds fi lled with rain blow from the southwest up across

the western and eastern coastlines of the subcontinent. In the west, the

ghats close to the coastline break the monsoon winds, causing much of

their water to fall along the narrow seacoast. On the other side of India,

the region of Bengal and the eastern coast receive much of the water. As

the winds move north and west through central India, they lose much

of their rain until, by the time they reach the northwest, they are almost

dry. Technically, then, much of the Indus River in the northwest fl ows

through a desert; rainfall is meager and only modern irrigation projects,

producing year-round water for crops, disguise the ancient dryness

of this region. For the rest of India, farmers and residents depend on

the monsoon for much of the water they will use throughout the year.

Periodically the monsoons fail, causing hardship, crop failures, and, in

the past, severe famines. Some observers have even related the “fatalism”

of Hinduism and other South Asian traditions to the ecology of the mon-

soon, seeing a connection between Indian ideas such as karma (action,

deeds, fate) and the necessity of depending for survival on rains that are

subject to periodic and unpredictable failure.

Stone Age Communities

From before 30,000 B.C.E. and up to (and in some cases beyond) 10,000

B.C.E. Stone Age communities of hunters and gatherers lived on the

subcontinent. The earliest of these human communities are known

primarily from surface fi nds of stone tools. Paleolithic (Old Stone Age)

peoples lived by hunting and gathering in the Soan River Valley, the

001-334_BH India.indd 5 11/16/10 12:41 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

6

Potwar plateau regions, and the Sanghao caves of northern Pakistan

and in the open or in caves and rock shelters in Madhya Pradesh and

Andhra Pradesh. The artifacts are limited: stone pebble tools, hand

axes, a skull in the Narmada River Valley, several older rock paintings

(along with others) at Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh, and, at a different

site in the same state, a natural weathered stone identifi ed by workers

as a “mother goddess.” Later Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) commu-

nities were more extensive with sites identifi ed in the modern Indian

states of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar.

Small parallel-sided blades and stone microliths (less than two inches

in length) were the tools of many of these Mesolithic communities who

lived by hunting and gathering and fi shing, with signs (later in this

period) of the beginnings of herding and small-scale agriculture.

The beginnings of pastoral and agricultural communities (that is, of

the domestication of animals and settled farming) are found in Neolithic

(New Stone Age) sites at various periods and in many different parts of

the subcontinent: in the Swat Valley and in Baluchistan in Pakistan, in

the Kashmir Valley, in regions of the modern Indian states of Bihar, Uttar

Pradesh, and in peninsular India (in the early third millennium

B.C.E.) in

northern Karnataka. The most famous and best known of Neolithic sites,

however, is the village of Mehrgarh, in northeastern Baluchistan at the

foot of the Bolan Pass. Excavations at Mehrgarh demonstrate that both

agriculture (the cultivation of wheat and barley) and the domestication

of animals (goats, sheep, and zebu cattle) developed during the seventh

millennium

B.C.E. (ca. 6500 B.C.E.). Although earlier scholars believed

that settled agriculture and the domestication of animals developed on

the subcontinent as a result of trading and importation from a limited

number of sites in the Near East, contemporary archaeologists have sug-

gested these developments were indigenous, at least in the regions of the

Baluchistan mountains and the Indo-Iranian borderlands (Possehl 2002;

Kenoyer 1998). Regardless of origins, by the third millennium

B.C.E., the

era in which the subcontinent’s earliest urban civilization appeared along

the length of the Indus River, that region was home to many different

communities—hunting and gathering, pastoral, and farming—and this

diverse pattern would continue throughout the Indus developments and

beyond.

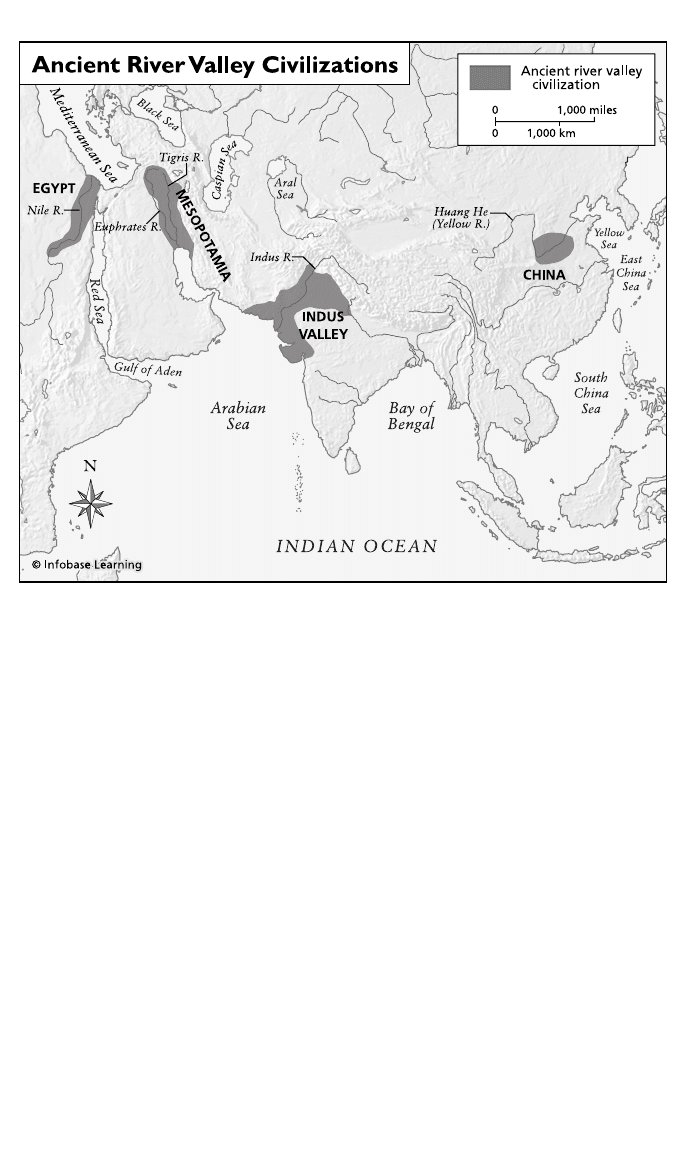

An Ancient River Civilization

The subcontinent’s oldest (and most mysterious) civilization was an

urban culture that developed its large city centers between 2600 and

001-334_BH India.indd 6 11/16/10 12:41 PM

7

LAND, CLIMATE, AND PREHISTORY

1900 B.C.E. along more than 1,000 miles of the Indus River Valley in

what is today both modern Pakistan and the Punjab region of north-

western India. At its height, the Harappan civilization—the name comes

from one of its cities—was larger than either Egypt and Mesopotamia,

its contemporary river civilizations in the Near East. But by 1900

B.C.E.

most of Harappa’s major urban centers had been abandoned and its cul-

tural legacy was rapidly disappearing, not just from the region where it

had existed, but also from the collective memories of the peoples of the

subcontinent. Neither its civilization nor any aspect of its way of life

appear in the texts or legends of India’s past; Harappan civilization was

completely unknown—as far as scholars can tell today—to the people

who created and later wrote down the Sanskrit texts and local inscrip-

tions that are the oldest sources for knowing about India’s ancient past.

In fact, until it was rediscovered by European and Indian archaeologists

in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Harappan civilization had com-

pletely vanished from sight.

Who were the Harappan peoples? Where did they come from and

where did they go? For the past 150 years archaeologists and linguists

have tried to answer these questions. At the same time, others from

inside and outside Indian society—from European Sanskritists and

FINDING HARAPPA

T

races of the Harappan civilization were discovered only in the

1820s when a deserter from the East India Company Army

happened upon some of its ruins in a place called Haripah. This was

the site of the ancient city of Harappa, but in the 19th and early

20th centuries its ruins were thought to date only to the time of

Alexander the Great (ca. fourth century B.C.E.). In the early 1920s,

the British Archaeological Survey of India, under the directorship of

John Marshall, began excavating the sites of Harappa and of Mohenjo-

Daro. The excavations produced a number of stamped seals, which

puzzled and interested the archaeologists, but the site’s great antiquity

was not recognized until 1924 when Marshall published a description

of the Harappan seals in the Illustrated London News. A specialist on

Sumer read the article and suggested that the Indian site might be very

ancient, contemporaneous with Mesopotamian civilization. The true

date of Harappan civilization was subsequently realized to be not the

fourth–third centuries B.C.E. but the third millennium B.C.E.

001-334_BH India.indd 7 11/16/10 12:41 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

8

British imperialists to, more recently, Hindu nationalists and their

secularist Indian opponents—have all sought to defi ne and use the

Harappan legacy.

Harappan civilization developed indigenously in the Indus River

Valley. Its irrigation agriculture and urban society evolved gradually

out of the smaller farming communities in the region, made possible

by the Indus region’s dry climate and rich alluvial soil. By the middle of

the fourth millennium

B.C.E. these agricultural communities had begun

to spread more widely through the Indus Valley region. What caused

an extensive urban, unifi ed culture to develop out of the agricultural

settlements of the region may never be known. But between 2600 and

1900

B.C.E. Harappan civilization appeared in what scholars call its

“mature phase,” that is, as an extensive civilization with large urban

centers supported by surrounding agricultural communities and with a

unifi ed, distinctive culture. Mature Harappan settlements are marked,

as their archaeological artifacts show, by increased uniformity in styles

of pottery, by their widespread use of copper and bronze metallurgy and

tools, by a uniform system of weights and measures, by baked brick

001-334_BH India.indd 8 11/16/10 12:41 PM

9

LAND, CLIMATE, AND PREHISTORY

architecture, by planned layouts of cities with extensive drainage sys-

tems, by specialized bead-making techniques, and by distinctive carved

steatite (soapstone) seals fi gured with animals and symbols that may

represent a script.

Harappan civilization was at the southeastern edge of an intercon-

nected ancient world of river civilizations that included Mesopotamia

in Iraq and its trading partners farther west. Indus contacts with this

ancient world were both overland through Afghanistan and by water

from the Indus delta region into the Arabian Gulf. A wide variety of

Harappan-style artifacts, including seals, beads, and ceramics, have

been found in sites at Oman (on the Persian Gulf) and in Mesopotamia

itself. Mesopotamian objects (although much fewer in number) have

also been found at Harappan sites. Mesopotamian sources speak of a

land called “Meluhha” with which they traded, from as early as 2600

B.C.E. to just after 1800 B.C.E. Scholars think Meluhha was the coastal

region of the Indus Valley.

Urban Harappan civilization in its mature phase was at least twice

the size of the two river valley civilizations farther to the east, either

ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia. Harappan settlements spread across an

area of almost 500,000 square miles and stretched from the Arabian sea-

coast north up the Indus River system to the foothills of the Himalayas,

west into Baluchistan, and south into what is modern-day Gujarat.

The total number of settlements identifi ed with the mature phase of

Harappan civilization is currently estimated at between 1,000 to 1,500.

Out of these, approximately 100 have been excavated. It is worth not-

ing, however, that the size of these mature Harappan settlements can

vary widely, with most sites classifi ed as small villages (less than 10

hectares, or 25 acres, in size) and a few as towns or small cities (less

than 50 hectares, or 124 acres, in size). Only fi ve large cities have been

identifi ed thus far in the urban phase of the Indus River civilization: Of

these two, Mohenjo-Daro in Sind and Harappa in the Punjab are the

best known and the largest, each perhaps originally one square mile in

overall size.

Scholars now agree that not one but two great rivers ran through

the northwest of the subcontinent at this time: the Indus itself (fl owing

along a course somewhat different from its current one) and a second

river, a much larger version of the tiny Ghaggar-Hakra River whose

remnants still fl ow through part of the region today. This second river

system paralleled the course of the ancient Indus, fl owing out of the

Himalaya Mountains in the north and into the Arabian Sea. By the end

001-334_BH India.indd 9 11/16/10 12:41 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

10

of the Harappan period, perhaps as a result of tectonic shifts in the

northern Himalayas, much of this river had dried up, and its tributary

headwaters had been captured both by the Indus itself and by rivers

fl owing eastward toward the Bay of Bengal. Some suggest this was part

of an overall climate change that left the region drier and less able to

sustain agriculture than before. Animals that usually inhabited wetter

regions—elephants, tigers, rhinoceroses—are commonly pictured on

seals from Harappan sites, but the lion, an animal that prefers a drier

habitat, is conspicuously absent.

Controversy surrounds contemporary efforts to identify and name

this second river—and indeed the Indus Valley civilization itself.

“Indigenist” Hindu nationalist groups argue that Indian civilization

originated in the Indus Valley and later developed into the culture

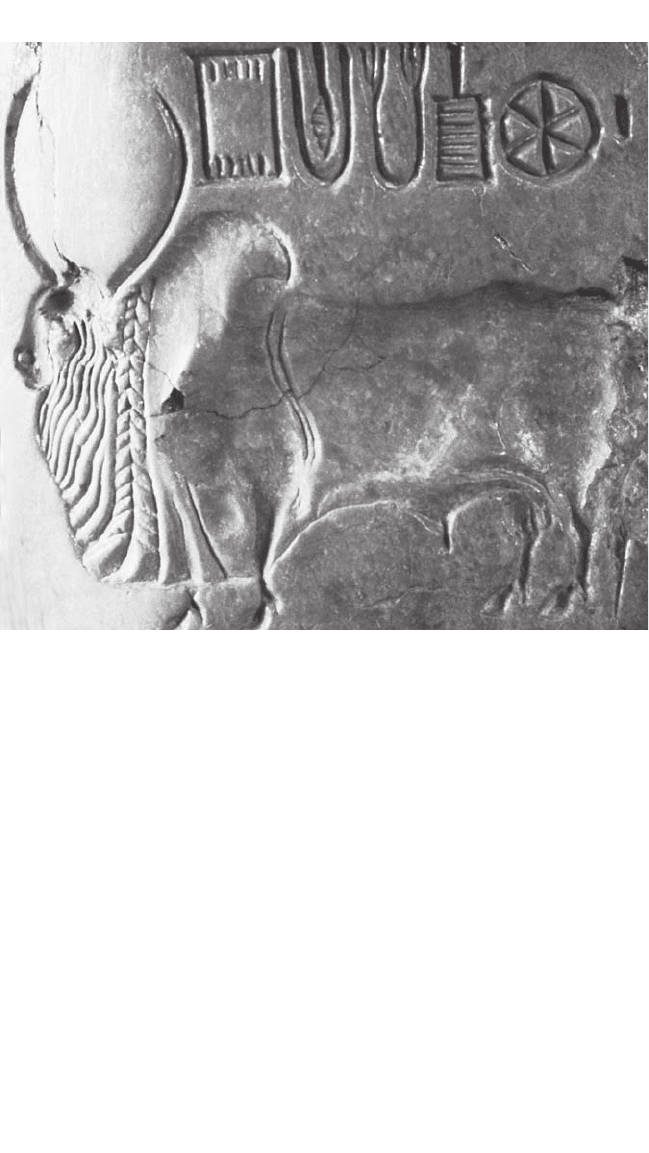

A zebu bull seal from Mohenjo-Daro. The Brahman, or zebu, bull on this Mohenjo-Daro seal is

an animal indigenous to the subcontinent. Although zebu bull motifs are common in Indus art,

the bull itself is only rarely found on seals and usually on seals with short inscriptions.

(© J. M.

Kenoyer, courtesy Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan)

001-334_BH India.indd 10 11/16/10 12:41 PM

11

LAND, CLIMATE, AND PREHISTORY

that produced the ancient texts of Hinduism, with some of its peoples

migrating “out of India” to spread the indigenous Indian language far-

ther to the east. In this context, journalists, scholars, and some archae-

ologists of the indigenous persuasion argue that the second river in the

Indus Valley must be the ancient Sarasvati, a river mentioned in the

oldest text of Hinduism, the Rig-Veda, but never identifi ed in modern

times. Indus civilization, according to this argument, should be called

the “Sarasvati Civilization” or the “Indus Sarasvati Civilization” to

indicate that it was the originating point for the later development of

Hinduism and Indian civilization (Bryant 2001).

Harappan Culture

Mature Harappan cities were trading and craft production centers, set

within the mixed economies—farming, herding, hunting and gather-

ing—of the wider Indus region and dependent on these surrounding

economies for food and raw materials. Mesopotamian records indicate

that the Meluhha region produced ivory, wood, semiprecious stones

(lapis and carnelian), and gold—all known in Harappan settlements.

Workshops in larger Harappan towns and sometimes even whole settle-

ments existed for the craft production of traded items. Bead-making

workshops have been found at Chanhu-Daro in Sind and Lothal near

the Gulf of Cambay in Gujarat. These workshops produced sophis-

ticated beads in a wide range of materials, from carnelian and other

semiprecious stones to ivory and shell. Excavations have turned up

a wide range of distinctive Harappan products: Along with beads and

bead-making equipment, these include the square soapstone seals char-

acteristic of mature Harappan culture, many different kinds of small

clay animal fi gurines—cattle, water buffalo, dogs, monkeys, birds,

elephants, rhinoceroses—and a curious triangular shaped terra-cotta

cake that may have been used to retain heat in cooking.

Harappan settlements were spread out over a vast region. Nevertheless

“their monuments and antiquities,” as the British archaeologist John

Marshall observed, “are to all intents and purposes identical” (Possehl

2002, 61). It is this identity that allows discussion about Harappan cit-

ies, towns, and villages of the mature period (2600–1900

B.C.E.) as a

single civilization. While scholars can only speculate about the nature

of Harappan society, religion, or politics, they can see its underlying

unity in the physical remains of its settlements.

Beads of many types and carved soapstone seals characterized

Harappan culture. In addition Harappans produced a distinctive

001-334_BH India.indd 11 11/16/10 12:41 PM