Walsh J.E. A Brief History of India

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

212

of India made up of 11 provinces, all the princely states, and a small

number of territories. The provinces were to be run by elected Indians

and the princely states by the princes. At the act’s center was the “steel

frame” that would preserve British control over India: The viceroy and

his administration remained in control of the central government with

a separate, protected budget and authority over defense and exter-

nal affairs (Jalal 1985, 17). Two central legislative houses were also

included in the act but never functioned, rejected for different reasons

by both the princes and the Congress. Provincial autonomy, however,

began in 1937 after nationwide elections that enfranchised 35 million

Indians (about one-sixth of India’s adult population).

Congress in Power

The Congress Party swept the provincial elections of 1937, winning 70

percent of the total popular vote and the right to form governments in

Birla Mandir, New Delhi. The Lakshmi Narayan Temple (commonly known as the Birla

Mandir, or “temple”) was built by the industrialist B. D. Birla in the late 1930s. The Birlas

were major fi nancial supporters of Mohandas Gandhi, and Gandhi himself dedicated the

temple at its opening in 1938. The ornate, pink-colored temple was dedicated to Vishnu

(Narayan) and his wife Lakshmi. Among the marble designs on its inside are panels illustrat-

ing the Bhagavad Gita.

(courtesy of Judith E. Walsh)

001-334_BH India.indd 212 11/16/10 12:42 PM

213

GANDHI AND THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENT

eight out of 11 provinces: Madras, Bombay, Central Provinces, Bihar,

United Provinces, Northwest Frontier, Orissa, and Assam. Regional

parties won control of three out of the four Muslim majority provinces:

Bengal, Punjab, and Sind. (Congress had won the fourth, the Northwest

Frontier.) The Muslim League, in contrast, won only 5 percent of the

total Muslim vote—109 seats out of 482 Muslim contests—and none of

the Muslim majority provinces.

In their provincial governments and coalitions, winning Congress

politicians made few concessions either to Muslim representatives or

to Muslim sensibilities. In the United Provinces, Congress offi cials

told Muslim League representatives that they could participate in the

government only if they left the league and joined the Congress Party.

Congress-dominated provincial assemblies sang “Bande Mataram,” and

regional Congress discourse extolled the virtues of the cow, the Hindi

language, and the Devanagari script. For Jinnah, working later in the

1940s to rebuild the Muslim League, Congress provincial governments

provided a clear illustration of the dangers Islam and Indian Muslims

would face in an India ruled by a Hindu-dominated party.

On the national level, Gandhi and the Congress “old guard” faced a

challenge from the party’s left wing. In 1938 Subhas Bose won election

as Congress president, supported by leftist and socialist Congress mem-

bers. He was opposed by Gandhi, Congress businessmen, and more

moderate Congress politicians. Bose and Gandhi had been opponents

within the Congress, disagreeing on economic policies and political

tactics. Unlike Nehru, however, Bose was unwilling to yield to Gandhi’s

overall leadership. Gandhi tolerated Bose as Congress president for

the fi rst term, but when Bose narrowly won reelection the following

year, Gandhi engineered the resignations of most Working Committee

members. Bose worked alone for six months before giving up and

resigning the presidency. He and his brother Sarat resigned also from

the Congress Working Committee and returned to Bengal to form their

own party, the Forward Block, a left-wing coalition group.

Pakistan

After the losses of the 1937 election, Jinnah had to rebuild the Muslim

League on a more popular basis. To do so, by the 1940s he was advo-

cating the idea of “Pakistan” and stressing the theme of an Islamic

religion in danger. At the 1940 Lahore meeting of the Muslim League,

Jinnah declared—and the League agreed—that Muslims must have

an autonomous state. “No constitutional plan would be workable in

001-334_BH India.indd 213 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

214

this country or acceptable to the Muslims,” the League stated in its

1940 Lahore Resolution, unless it stipulated that “the areas in which

the Muslims are numerically in a majority . . . should be grouped to

constitute ‘Independent States’ in which the constituent units shall be

autonomous and sovereign” (Hay 1988, 228). The idea of a separate

Islamic Indian state had been expressed 10 years earlier by the Urdu

poet Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938). The imagined state had even been

given a name by a Muslim student at Cambridge in 1933: He called it

“Pakistan,” a pun that meant “pure land” and was also an acronym for

the major regions of the Muslim north (P stood for the Punjab, a for

Afghanistan, k for Kashmir, s for Sindh, and tan for Baluchistan).

The diffi culty with the idea of Pakistan was that it did not address

the political needs of most Indian Muslims. Most Muslims were scat-

tered throughout India in regions far from the four northern Muslim

majority provinces. Minority Muslim populations needed constitu-

tional safeguards within provincial and central governments, not a

Muslim state hundreds, even thousands, of miles from their homes.

Jinnah himself had worked throughout his career to establish just

such safeguards within a strong centralized government. Some schol-

ars have suggested that his support for Pakistan in the 1940s began

as a political tactic—a device to drum up Muslim support for a more

popularly based Muslim League and a threat to force concessions from

Congress leaders, particularly from Gandhi for whom the idea of a

divided India was anathema.

The idea of a state ruled by Islamic law where Muslim culture

and life ways could reach full expression had great appeal to Indian

Muslims. Muslims in majority regions imagined Pakistan as their own

province, now transformed into an autonomous Muslim state. Muslims

in minority provinces (always Jinnah’s strongest constituency) thought

of Pakistan less as a territorial goal than as a political identity—a

Muslim national identity—that would entitle Indian Muslims to a pro-

tected position within any central Indian government. Even as late as

1946–47, Muslims in minority provinces supported the idea of Pakistan

with little sense of what it might mean in reality. As one Muslim, a stu-

dent in the United Provinces at that time, later recalled,

Nobody thought in terms of migration in those days: [the

Muslims] all thought that everything would remain the same,

Punjab would remain Punjab, Sindh would remain Sindh, there

won’t be any demographic changes—no drastic changes any-

way—the Hindus and Sikhs would continue to live in Pakistan

. . . and we would continue to live in India. (Pandey 2001, 26)

001-334_BH India.indd 214 11/16/10 12:42 PM

215

GANDHI AND THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENT

Quit India!

On September 3, 1939, the viceroy, Victor Alexander John Hope, Lord

Linlithgow (1887–1952), on orders from Britain, declared India at

war with Germany. This time, however, the Indian National Congress

offered cooperation in the war only on condition of the immediate

sharing of power in India’s central government. In April 1942, in an

attempt to win over Congress leaders, the British government fl ew Sir

Stafford Cripps (a personal friend of Nehru’s) to India. With British

prime minister Churchill completely opposed to any concessions to

Indian independence, even as a possible Japanese invasion loomed on

India’s eastern borders, Cripps offered Congress leaders only a guar-

antee of dominion status (a self-governing nation within the British

Commonwealth) at the end of the war. Gandhi called Cripps’s offer “a

post dated cheque” (Brecher 1961, 109).

With Cripps’s mission a failure, Gandhi and the Congress opened a

new civil disobedience campaign: “Quit India!” The government imme-

diately imprisoned all major Congress leaders. Nevertheless, an unco-

ordinated but massive uprising spread throughout the country leading

to more than 90,000 arrests by the end of 1943. Protests were marked

by sporadic violence and included attacks on railways, telegraphs, and

army facilities. The British responded with police shootings, public

fl oggings, the destruction of entire villages, and, in eastern Bengal, by

aerial machine-gun attacks on protesters.

Beginning in 1942 and lasting through 1946 a terrible famine erupted

in Bengal. The famine was caused not by bad weather but by the con-

junction of several other factors: the commandeering of local foods to

feed the British army, the wartime stoppage of rice imports from Burma,

profi teering and speculation in rice, and perhaps also a rice disease that

reduced crop yields. By 1943 tens of thousands of people had migrated

into Calcutta in search of food and an estimated 1 million to 3 million

people had died from famine-related causes.

Independence

At the end of World War II, with a new Labor government in place,

huge war debts to repay, and a country to rebuild, the British wanted to

exit India. The combined costs of war supplies and of an Indian army

mobilized at 10 times its normal strength had more than liquidated

India’s debt to Great Britain. Instead of home charges, it was now Great

Britain that was in debt to India. British offi cials in both London and

New Delhi knew Britain could no longer maintain its empire in India.

001-334_BH India.indd 215 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

216

The biggest obstacle to British withdrawal, however, was the politicized

communal identities that had grown up over the 20th century, fostered by

Indian nationalists and politicians and by the British themselves through

their “divide and rule” tactics. Such identities divided Muslims and

Hindus, but they also existed among Sikhs, South Indian “Dravidians,”

and Untouchables. The problem was how to reunite all these political

groups within the majoritarian electoral structures of a modern demo-

cratic state, while simultaneously protecting their minority interests.

The Congress Party won 91 percent of all non-Muslim seats in

the winter elections of 1945–46 and was returned to power in eight

provinces. By the 1940s Congress had built an all-India organization

with deep roots throughout the country and with a unity and identity

developed over its more than 50 years of struggle against British rule.

The party’s goal was a strong, centralized India under its control. For

Congress socialists, like Nehru, such centralization would be essen-

tial if India was to be rebuilt as an industrialized, prosperous state.

Minority groups’ fears over such centralization, meanwhile, were an

irritant for Congress. From the Congress perspective political differ-

ences between Hindus and Muslims could wait for resolution until

after independence.

BOSE’S INDIAN

NATIONAL ARMY

I

n 1941 Subhas Bose’s arrest for sedition was imminent in Calcutta,

and he fl ed India, seeking sanctuary with the Nazi government in

Germany. In 1942 he was taken to Japan by the Germans and then to

Singapore, now under Japanese control. In Singapore, Bose formed

the Indian National Army (INA), drawing his recruits from the 40,000

Indian prisoners of war interned in Japanese camps. His new army

fought with the Japanese against the British in Burma.

Many Indians identifi ed with the INA and saw it as a legitimate part

of the freedom struggle against Great Britain. In 1945, the same year

that Bose died in a plane crash, the British government put several

hundred captured INA offi cers on trial for treason in New Delhi. Both

Congress and the Muslim League protested against the trials, but it

was only after two students were killed by police in Calcutta riots

against the trials that charges against most defendants were dropped.

001-334_BH India.indd 216 11/16/10 12:42 PM

217

GANDHI AND THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENT

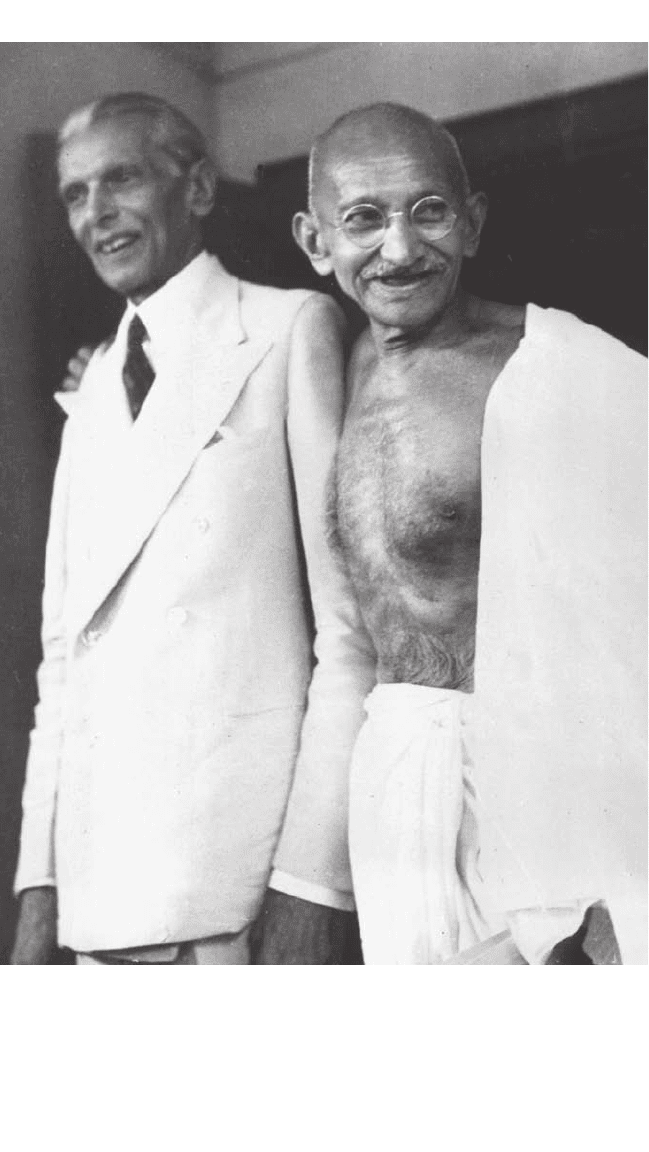

Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Mohandas K. Gandhi both joined the Indian nationalist movement

around the time of World War I. They would be political opponents for the next 30 years, dif-

fering not only on issues of political substance but also (as the photo shows) on questions of style

and personal demeanor. By 1948 both men would be dead: Gandhi from an assassin’s bullet and

Jinnah from disease and ill health. This photo dates to 1944 and a meeting at Jinnah’s house on

September 9 to discuss Hindu-Muslim confl icts in Bombay city.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

001-334_BH India.indd 217 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

218

In contrast to Congress, Jinnah’s Muslim League existed mostly

at the center. The league was a thin veneer that papered over a wide

range of confl icting Muslim interests in Muslim majority and minor-

ity regions—a veneer that Jinnah used, nevertheless, to justify the

league’s (and his own) claims to be the “sole spokesman” of Indian

Muslims (Jalal 1985). By 1945 Jinnah’s advocacy of an independent

Muslim state and his campaign of “Islam in danger” had rebuilt the

Muslim League. It had also completely polarized the Muslim elector-

ate. In the winter elections of 1945–46 the Muslim League reversed

its losses of eight years earlier, winning every Muslim seat at the

center and 439 out of 494 Muslim seats in the provincial elections.

The politicized atmosphere of the 1940s destroyed long-established

communal coalition parties and governments in both Bengal and

the Punjab, replacing them with Muslim League governments. For

Muslims, religious identity was now the single most important ele-

ment of political identity. For the league (and more broadly for the

Muslim electorate) that identity needed political protection through

constitutional safeguards before independence arrived.

A British cabinet mission, sent to India after the 1945–46 elections,

was unable to construct a formula for independence. Jinnah refused to

accept a “moth eaten” Pakistan, a Muslim state that would consist of

parts of Bengal and parts of the Punjab (Sarkar 1983, 429). Congress

refused a proposal for a loose federation of provinces. Plans for an

interim government foundered on arguments over who would appoint

its Muslim and Untouchable members. As the Congress left wing

organized railway and postal strikes and walkouts, Jinnah, intending

to demonstrate Muslim strength, called for Muslims to take “direct

action” on August 16, 1946, to achieve Pakistan.

Direct Action Day in Calcutta triggered a series of Hindu-Muslim

riots throughout northern India unprecedented in their ferocity and

violence. Between August 16 and 20 Muslim and Hindu/Sikh mobs

attacked one another’s Calcutta communities killing 4,000 people

and leaving 10,000 injured. Rioting spread to Bombay city, eastern

Bengal, Bihar, the United Provinces, and the Punjab. In Bihar and the

United Provinces Hindu peasants and pilgrims massacred at least 8,000

Muslims. In the Punjab Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs turned on one

another in rioting that killed 5,000 people.

As public order disintegrated, Clement Attlee, the British prime

minister, declared the British would leave India by June 1948. When

Lord Louis Mountbatten (1900–1979), India’s last British viceroy,

reached India in March 1947, the transfer of power had already been

001-334_BH India.indd 218 11/16/10 12:42 PM

219

GANDHI AND THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENT

advanced to August of that year. The British moved peremptorily to

make their fi nal settlement of political power. When Nehru privately

rejected “Plan Balkan”—so named because it transferred power to

each of the separate Indian provinces much as had occurred in the

Balkan States prior to World War I—the British settled on a plan

that granted dominion status to two central governments, India

and Pakistan (the latter to be composed of a partitioned Bengal and

Punjab, plus the Northwest Frontier Province and Sind). Congress,

the Muslim League, and Sikh leaders agreed to this plan on June 2,

1947. The British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act on

July 18 for implementation August 15.

India became independent at midnight on August 14, 1947. The

transfer of power took place at Parliament House in New Delhi. “Long

years ago we made a tryst with destiny,” Nehru said in his speech that

night,

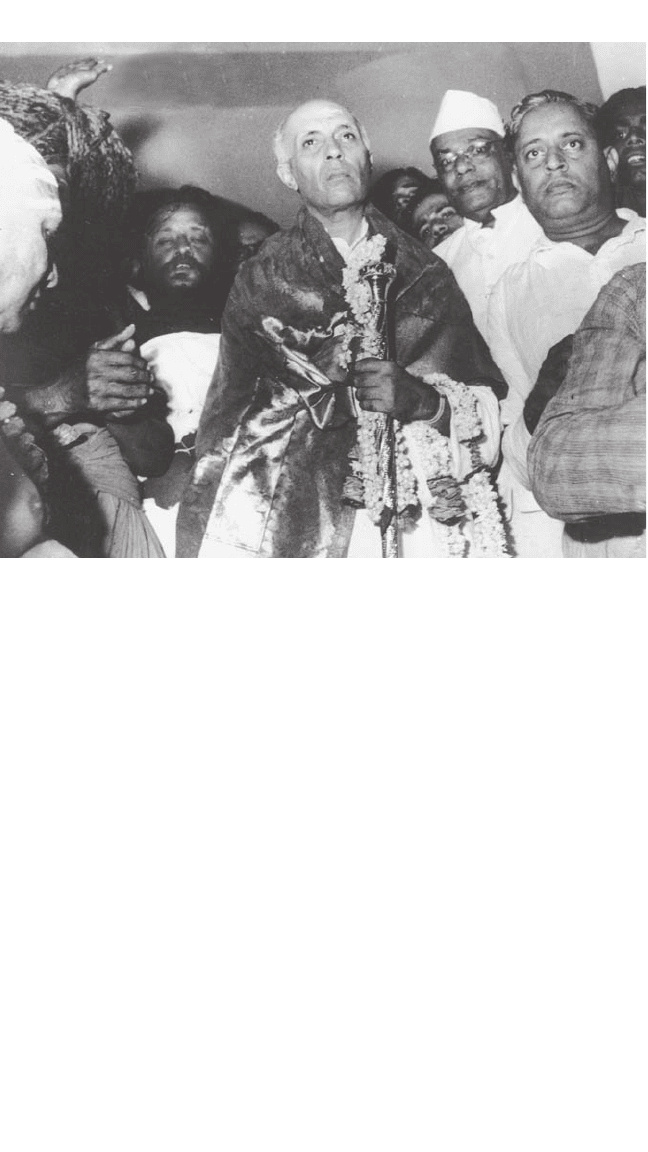

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, 1947. Newly installed as prime minister, Nehru holds a gold

mace presented to him on the evening of Indian independence, August 14, 1947. The white

markings on his forehead were made by a priest during an earlier puja (prayer service).

(AP/Wide World Photos)

001-334_BH India.indd 219 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

220

and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not

wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke

of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake

to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely

in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an

age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed finds

utterance. (Brecher 1961, 137)

Nehru became India’s fi rst prime minister. Lord Mountbatten, at

the invitation of Congress, served as governor-general of the Indian

Dominion through June 1948. Regulations governing the new state

devolved from the Government of India Act of 1935.

Partition

Two secret British commissions, directed by the British barrister Sir

Cyril Radcliffe, drew the boundaries that would separate India from

THE PRINCES

T

he British made no provision for the Indian princes in the transfer

of power, the viceroy simply informing the princes that they must

make their own arrangements with one or another of the new states.

Vallabhbhai (Sardar) Patel oversaw negotiations for India with the princes,

offering generous allowances in exchange for the transfer of their states.

By 1947 all but three states—Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Kashmir—

had transferred their territories, most to India. Both Junagadh on the

Kathiawad peninsula and Hyderabad in the south were Hindu-majority

states ruled by Muslim princes. By 1948 the Indian government and its

army had forced both princes to cede their states to India.

Kashmir, in contrast, was a Muslim-majority state bordering both India

and Pakistan but ruled by a Hindu king, Hari Singh. In October 1947, faced

with a Muslim uprising against him, Singh ceded his kingdom to India.

At this point Kashmir became the battleground for Indian and Pakistani

invading armies. A January 1949 cease-fi re, brokered by the United

Nations, drew a boundary within the province, giving India administrative

control over two-thirds of the region and Pakistan the remaining one-

third. Under the terms of the cease-fi re India agreed to conduct a plebi-

scite in Kashmir that would determine the region’s political fate. India’s

subsequent refusal to conduct the plebiscite caused Kashmir to remain in

turmoil and a source of Indian and Pakistan confl ict into the 21st century.

001-334_BH India.indd 220 11/16/10 12:42 PM

221

GANDHI AND THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENT

east and west Pakistan. The boundaries were not announced until

August 17, two days after independence. It was only then that the real

impact of partition began to be felt, as majority communities on both

sides of the border attacked, looted, raped, and murdered the remain-

ing minorities. Within a month newspapers were reporting 4 million

migrants on the move in northern India. One nine-coach train from

Delhi, crammed with refugees, crossed the border into Pakistan with

only eight Muslim survivors on board; the rest had been murdered

along the way (Pandey 2001, 36). Estimates of people killed in parti-

tion violence ranged from several hundred thousand to 1 million. The

entire population of the Punjab was reshaped in the process. By March

1948 more than 10 million Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs had fl ed their

former homes on either side of the border to become refugees within

the other country.

Gandhi’s Last Campaign

During 1945–47 Gandhi took no part in the fi nal negotiations for

independence and partition. He could neither reconcile himself to the

division of India nor see an alternative. Instead he traveled the villages

of eastern India attempting to stop the spreading communal violence.

In Calcutta in 1947 Gandhi moved into a Muslim slum, living with

the city’s Muslim mayor and fasting until the city’s violence ended. In

January 1948 he conducted what would be his last fast in Delhi, bring-

ing communal confl ict to an end in the city and shaming Sardar Patel,

now home minister of the new government, into sending Pakistan

its share of India’s prepartition assets. On January 27, 1948, Gandhi

addressed Delhi Muslims from a Muslim shrine. Three days later, on

January 30, 1948, the elderly Mahatma was shot to death as he walked

to his daily prayer meeting. His murderer, Naturam V. Godse, was a

right-wing Hindu with ties to the paramilitary RSS. Gandhi’s assas-

sination had been planned by a Brahman group in Pune that thought

Gandhi dangerously pro-Muslim. Godse was ultimately tried and

executed for his act. Revulsion against Gandhi’s assassination provoked

anti-Brahman riots in the Mahasabha strongholds of Pune, Nagpur, and

Bombay and caused the RSS to be banned for a year.

Gandhi had not attended the ceremonies marking independence and

partition, nor had he asked for or accepted any role in the new govern-

ment. The nationalist movement he had led since 1920 concluded with

India’s independence but also with a division of Indian lands, homes,

and people more terrible than anything imagined. Yet Gandhi had raised

001-334_BH India.indd 221 11/16/10 12:42 PM