Walker J.M. The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Figure 12 Gloriana Mixture Tobacco Tin; Surburg Tobacco Co., 1893. Collection of the author

138

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect -

2011-03-24

on its owner. Why, then, do we have tins – such as the early biscuit tins

– on which the product’s name appears only (and often not completely)

on the bottom? Because we think in images, not words. To make a tin

with an actual image is to give its purchaser/owner a tangible piece of

the history – of the moment, of the personality that is displayed. Even

if a person does not understand the image, the impression is there, fixed

in memory, ready to tap into factual public knowledge offered at school,

through entertainment, from friends, or found by chance. My own interest

in British royal families began at the moment my mother told me to tidy

up my hair clips and gave me a toffee tin with a picture of the newly

crowned George VI, Queen Elizabeth, and the little princesses. They were

not dressed as royalty on the tin, nor was the picture current in the late

1950s, but, my mother told me, this was because they were real, not in

a storybook. How that toffee tin found its way into the southern

Appalachian Mountains is a mystery to me, but that image gave me an

idea of monarchy, a link to the sphere of public memory in which I would

soon find the first Elizabeth and various other figures who did look like

the books I’d been reading. But their reality, for me, grew from the reality

of the image on the tin, not the other way around. Had the local A & P

carried toffee tins, I would have bought every one, collecting the many

versions of the young royal family that I now know exist in that series.

People think in pictures. If we can’t have pictures, then we need pictorial

words – Red Man, Bond Street, Pall Mall. The closer the word is to the

image, the more likely we are to make it our own and to link our personal

memories with that modern sphere of public space. Ironically, when I

wrote of the early icons, it was to make the point that people needed to

be pulled together by a collectively recognizable image. Today, as

bombarded by the visual as we are, we need a particular piece of that public

space to call our own, to mine out our own versions of an image and take

it home in our heads. The icons we take with us – home in our heads or

out into the world – contain elements of shared history and individual

perception. Did I share a knowledge of the picture on that toffee tin with

any number of eight-year-old girls in England? Definitely. Did I perceive

the Royal Family in the same way as an average English girl of my age?

Definitely not.

The split in this book is between the icons which are tied directly from

history to history – from the Armada to the Battle of Trafalgar – and the

icons which we need to serve two purposes: making that link with history,

but also speaking to our own experiences. As we have become collec-

tively more educated, we have become individually more isolated. In

1837–1910: The Shadow of a Paternalistic Queenship 139

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

both paradigms, the early-modern and the post-modern, the icon is a point

of transformation.

c.1885: the Pre-Raphaelites colonize Elizabeth

The 1885 I use here is an arbitrary date, taking circa in its most useful

sense. The prints and engravings from the years 1875 to 1896 are not neces-

sarily in the chronological order of the paintings from which most of them

were made, but neither does chronology play as important a role in my

argument as it did for the art linked to the Spanish Match. Once again,

we need to recognize the differences between the reign of Elizabeth and

the reign of Victoria. Elizabeth wielded real life-and-death political power;

Victoria’s role in the governing of her people was not without power –

she could urge that attention be paid or put a royal stick in the spokes

of programs she disliked – but she was not the divinely empowered

monarch of the Renaissance, nor could she ever be, for all that she had

the title of Empress. Celebrating Elizabeth’s power, glory, or conquests

was thus an exercise in distinctly bad taste. We have no grand paintings

of Gloriana from the Victorian period. But we do have scenes from English

history; if these scenes have a unifying topic, it may be that of putting

Elizabeth in her place: the past.

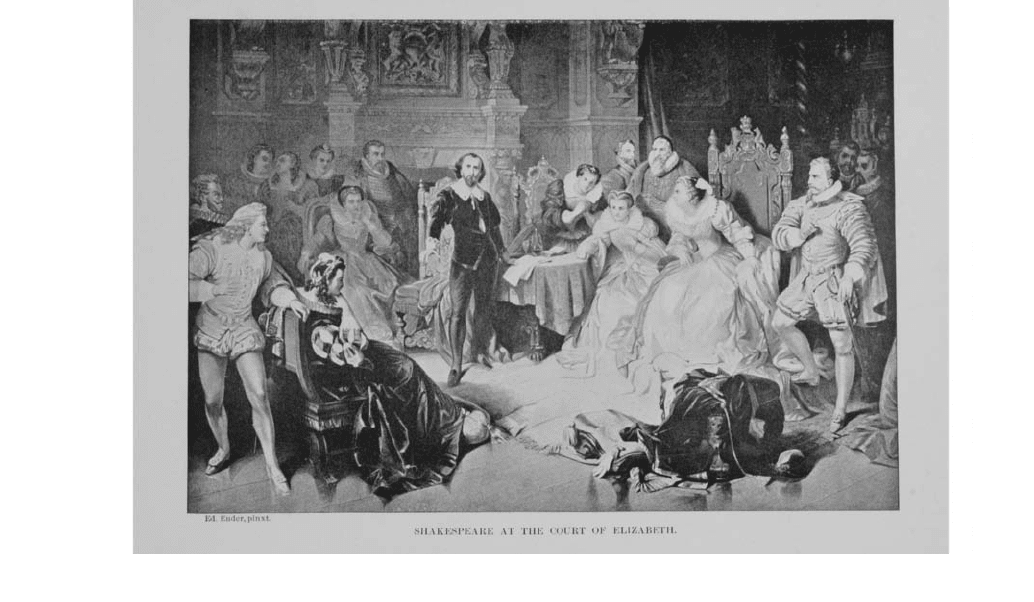

As a number of scholars have observed, conflating Elizabeth with

Shakespeare was an effective way both to define an age and to canonize

a playwright. Shakespeare was extremely popular during the Victorian

era, and making Elizabeth part of Shakespeare’s England was an acceptable

way to represent the mature queen without flaunting her royal powers.

There are so many pictures of Shakespeare reading to Queen Elizabeth

that they almost constitute a genre in Victorian painting.

6

Eduard Ender’s

painting of Shakespeare reading Macbeth to Queen Elizabeth and her

court, reproduced c.1880 as an engraving (Figure 13), is an excellent

example of this limited and limiting sort of Elizabeth icon. Very much

in the school of Ford Madox Brown’s 1851 painting (generally on display

in the British Tate) Geoffrey Chaucer Reading the “Legend of Custance” to

Edward III and his Court, at the Palace of Sheen, on the Anniversary of the

Black Prince’s Forty-fifth Birthday, the work is much more about Shakespeare

than it is about Queen Elizabeth. At the center of a circle formed by the

gowns of the seated women and the elaborate over-mantle, the dark-

clad, upright male figure stands out on the pale field of the curving forms

of women, dresses, and the effeminately (in comparison) clad men.

Shakespeare looks out of the frame, with only a slight turn of his torso

indicating any acknowledgment of the queen’s presence. Elizabeth herself

is the most dramatically (and sentimentally) inclined of all the figures

140 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

Figure 13 Shakespeare at the Court of Queen Elizabeth, engraving after the painting by Eduard Ender, c.1880

141

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect -

2011-03-24

focused on Shakespeare, and – although her dress takes up a dispropor-

tionate amount of space, she is clearly in the margin of the painting. For

in addition to the central circle he fills, Shakespeare is at the apex of a

triangle formed by the two dark figures in the foreground – the draped

footstool on the right and the dress of the seated woman on the left.

Finally, there is the queen’s besotted expression. Some women of her

court also gaze with awe and fascination, but most of the men are paying

only partial attention or – as is the man with the pointed beard at the

foot of the large pillar on the right – are in the act of turning disdain-

fully away.

Creating a relationship that did not exist between Elizabeth and

Shakespeare, this engraving, the painting it reproduces, and the collection

of paintings and engravings and prints that it represents all strive to

suggest that Elizabeth’s relationship with writers (or at least with this

writer) was one in which the power was vested in the writer, not the

monarch. Elizabeth gets marginal credit for having the good sense to

foster Shakespeare’s talent (more so than she did in reality or in Shakespeare

in Love) and for appreciating his genius, but this iconic Elizabeth is nearly

as powerless as the dead Elizabeth of the Gheeraerts painting. She has,

in fact, come close to being the devoted wife/mother figure of Victorian

narrative painting, every atom of her being focused on the accomplished

and dominant male. Here Elizabeth’s court is a stage worthy of

Shakespeare; we are not being told that Shakespeare was worthy of

Elizabeth’s golden age.

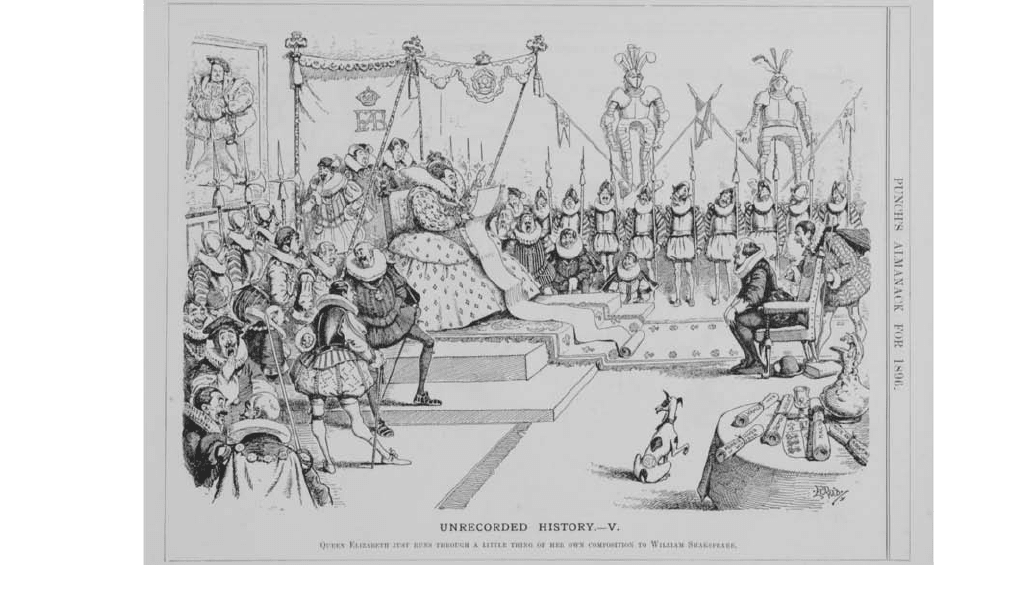

This historical misrepresentation did not go unnoticed or unremarked,

as is evidenced by the 1896 cartoon sketch from Punch (Figure 14). Titled

“Unrecorded History. V,” the cartoon shows a caricature of Queen

Elizabeth in the dress from the Ditchley portrait, seated on an elevated

throne, under a canopy bearing her initials (which would, incidentally,

block Shakespeare’s view of the enormous portrait of Henry VIII) reading

from an extremely long scroll. As the subtitle tells us with vast under-

statement, she “just runs through a little thing of her own composition.”

No one – certainly not Elizabeth or Shakespeare – looks good here. The

queen’s courtiers, soldiers, and ladies in waiting are all inattentive, busy

talking or rolling their eyes or in the process of falling asleep. Shakespeare

himself – a dumpy little figure – is indeed on the edge of his seat, but

we are in doubt as to the cause of this posture. Is he really interested,

really polite, really afraid to seem uninterested, or actually afraid of being

shaken back into attention by the courtier poking at his back? But the

real target of satire here is the group of paintings discussed above. The

Victorian desire to locate the genesis of Bardolatry back in the age of

142 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

Elizabeth, to show the queen as a frame for the accomplishments of one

of her subjects, to shift the emphasis from Shakespeare in the Age of

Elizabeth to Elizabeth in the Age of Shakespeare – all these take a beating

in the Punch cartoon. Furthermore, the comic mode of representation

itself takes dead aim at the elaborate Victorian set-pieces. The silly dog,

the ever-unrolling “little thing,” the huge but unseen portrait of Henry,

the queen’s pointed head, the Bard’s plump rump, the neglected state

papers on a table in the foreground, and the exaggerated suits of armor

hanging on the wall all parody the anachronistic and busy Victorian

detail of paintings such as Ender’s.

Shakespeare’s audience, however, was not the only role in which the

Victorians endeavored to cast Elizabeth. Another favorite version of her

life was the five worst years from her span of 70 – Elizabeth as a prisoner.

Here she could be brave (as in the Millais engraving) or dejected (as in

the Sherratt engraving), but in either case, the queen – or more accurately,

the princess – is quite without power over others. This plays to two

cultural preferences of the Victorian era – the reluctance to make Elizabeth

obviously more powerful than Victoria, and the desire to sentimentalize

any story involving a famous woman.

The more bathetic of the two, T. Sherratt’s engraving from R.

Hillingford’s painting (Figure 15), show Elizabeth huddled on a bare stone

bench, clutching an outsized handkerchief, glumly refusing to look in

the direction of the head jailer’s gesture – likely toward some amenities,

or at least an unblocked window, judging from the light. Here Elizabeth

is almost literally spineless, the reversed S curve of her body, when

continued, follows the curve of the arch above her, making her physically

at one with her cell, even as her face expresses nothing of the stub-

bornness and spirit and sheer political acumen that got the real Elizabeth

through these years. Here, stubbornness has become a bad case of the

sulks. While the men seem to pity her, their expressions are free from

any sort of admiration, and even the dog seems to want out the door as

quickly as possible. The only positive note in the frame is that the left

side of the image is darker than the right, with the jumbled figures in

the doorway further emphasizing Elizabeth’s isolation or singularity. But

whether this increased lighting is meant to symbolize Elizabeth’s coming

triumph and present virtue or is merely to show her despair in sharper

relief is impossible to guess.

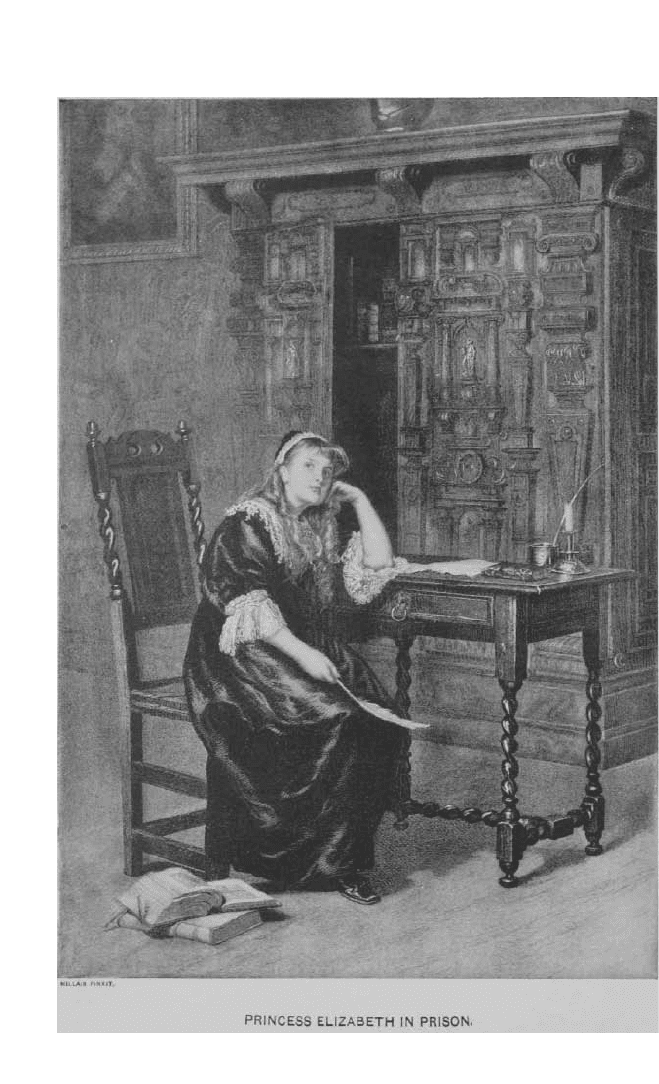

We are literally less in the dark with John Everett Millais’ engraving

after his own painting, “Elizabeth in Prison” (Figure 16). This prison,

while possibly in the royal apartments in the Tower, could be set at any

time during Elizabeth’s life, for her main activity seems to be study and

1837–1910: The Shadow of a Paternalistic Queenship 143

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

Figure 14 Unrecorded History V; Queen Elizabeth … William Shakespeare. From Punch’s Almanack for 1896

144

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect -

2011-03-24

145

Figure 15 “The Princess Elizabeth in the Tower”; engraving by T. Sherratt after the painting by R. Hillingford, c.1875

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect -

2011-03-24

writing. Not knowing what else to do with her, and because of the enlight-

ened views of her last step-mother, Catherine Parr, first Henry, then

Edward’s advisors, gave her a superlative education. If not for the title of

the picture, there’s little here to suggest a prison other than the plainness

of the room. Even that could pass for historical accuracy if Elizabeth’s

dress were more clearly of her own period. The princess has paper on the

desk/table, two open books on the floor, and holds a quill in her right

hand while she looks up toward the source of the light. She is resting her

cheek on her left hand, but the attitude is far from the head-propping

gesture of the dead queen in “Elizabeth with Time and Death” (see Figure

3). And her expression, especially with those eyes directed upward and

to her right, is thoughtful, but not gloomy. In the act of writing, in the

midst of study, thought is both natural and positive. The expression on

the face and the angle of the head could be read as pensive, but pensive

is a long way from either despair or gloom. We know that Millais was

concerned about the reproduction of her expression. In a letter to Mrs.

Hunt on 18 November 1880, the artist writes: “I will attend to all you

say about the proof of Elizabeth & see how it may be made much more

effective but the head is charming which [is] a great matter.”

7

Millais’

concern about the head as “a great matter” and his declaration that it is

“charming” suggest that he knew that the posture was ambiguous, but

was striving for the triumph of the positive over the negative, while still

showing that this was a struggle and thus a true triumph.

The final example of Victorian icons of Elizabeth is representative of

yet another popular sub-genre of the period: the Elizabeth and Mary

Stuart story. “Elizabeth and Mary Stuart” (Figure 17) shows a pastoral

confrontation between the two queens. Originally an illustration from

a book about Mary, the image requires attentive reading. As Dobson and

Watson quip, “In reality Elizabeth and Mary, Queen of Scots, never met,

but on the stage they have been doing so ever since John Banks composed

The Island Queen (1684).”

8

Not only is this image interesting in its own

right, but it is a radical revision of any early portrait of the queen.

In the Victorian print we see the two queens standing on level ground,

with Elizabeth, in white, in the right foreground, with Mary (darker in

both dress and expression) on the left, but only a step or two in the

background. The picture divides evenly between the two women, with

Elizabeth’s right glove and riding crop thrown on the ground between

them, presumably as a challenge. If so, it’s a challenge Mary seems more

than prepared to meet, as her left hand claws toward Elizabeth’s face.

Mary is restrained by one lady in waiting, while Elizabeth is backed up,

but not touched, by two gentlemen. Given that the source of this picture

146 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

1837–1910: The Shadow of a Paternalistic Queenship 147

Figure 16 “Princess Elizabeth in Prison.” Millais, engraving, after his own painting,

c.1880. Collection of the author

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24