Walker J.M. The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In 1800 we find the same song in another chapbook, but with the addition

of the following as the penultimate stanza:

Then all great men were good, and all good men were great,

And the props of the nation were the pillars of the State, Sir;

For the sovereign and the subject one interest supported,

And all our powerful alliance by all nations were courted.

Oh the golden days, &ec.

That chapbook also contains a set of lyrics using “Good Queen Bess” as

a ruler with which to measure and praise King George.

THE ALTERATION OF TIMES: or the Days of George the Third!

[1st verse]

Come listen my neighbours and hear a merry ditty,

Of a strange alteration in every town and city,

I’ll tell you of the times when Queen Bess rul’d the nation,

And take a view of things in their present situation.

O what an alteration is now to be seen,

Since the happy times when Elizabeth was Queen.

The middle lines are much the same as in the first song, but with better

syntax, 25 lines, without stanza breaks, of then-and-now statements

(with then definitely the winner); and the song concludes:

But now everybody’s business some people make their own,

And if they see you rise, they’ll strive to pull you down.

Thus happy they did live, sir, as you may plainly see,

And were a bright example for all their posterity,

May we follow their steps til we happily attain,

And the Lord restore the King to his royal throne again.

And long may he reign with glory and success,

And may he reign hereafter in heaven’s happiness.

43

The wish that the king might be restored to his royal throne is a reference

to the power held by the Prince of Wales, who, by July of 1784, was

shuttling regularly between Brighton and London. In 1788 George

undeniably succumbed to his now-famous madness, and three months

later Prime Minister Pitt introduced the Regency Bill to impose strictly

limited authority on the Prince of Wales, a legislation that was dropped

a few weeks later when George was said to have recovered. But a more

118 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

likely reading renders this dittie as bald-faced satire. In late 1795 George

III was stoned by an angry London crowd, and there had been bread riots

for months in various cities. January of 1800 saw the opening of the first

soup kitchen in London, an effort to relieve the acute food shortage.

George III continued in uncertain mental and physical health until the

issue could be no longer overlooked, and the Regency Act was passed in

1811. The king who made such a poor showing when compared with Good

Queen Bess had brought the country to its 1800 “present situation,” and

the situation was soup kitchens and starvation. It’s just as well that the

author of this song did not read that 1740 “history” in which even

Elizabeth’s maids ate steaks.

As Prince Regent, the future George IV came to power over a nation

that had lost a major colony in North America, had at one time or another

in the past 20 years been at war with fully half of Western Europe, and

was currently locked in a struggle with Napoleon’s quest for empire. 1811

was almost the midpoint between the 1805 victory of Trafalgar and the

1815 Battle of Waterloo.

Clearly, some sort of intervention was needed. Even sentimental

literature of the period cried out for the figure of Elizabeth. In 1809 Elizabeth

Somerville’s Aurora and Maria: or The Advantages of Adversity, A Moral Tale,

in which is Introduced a Juvenile Drama, Call’ed Queen Elizabeth or Old Times

New Revived appeared. The two little girls of the title – who have very odd

mothers – give the three-act play’s curtain speech, which purports to be

Elizabeth’s words upon hearing the news of the Armada victory.

Chance has bestowed on me an uncertain and an uncoveted crown;

but clemency and justice are beyond the power of chance to bestow.

They are the richest gifts of an higher and better governed world,

whose slightest favor I would purchase could it be bought by the willing

sacrifice of all my boasted greatness! Nor would I from the lowest state

in nature, be one atom less a Christian, to be more than queen! This

is a day of rejoicing; from this time may we anticipate the glad tidings

of peace, and again trace the truant smile of content on the cheek of

the childless and forlorn. From this day may every British son triumph

in our victories, and proudly boast his scars, as fresh gained laurels in

a mother’s cause.

44

At a time when the new French Armada had so recently been laid low

by Nelson, the idea of little girls speaking sentimental lines of a bygone

queen lies in an uneasy praxis between the culturally interesting and the

openly maudlin. My point, however, mercifully does not require that I

1660–1837: The Shadow of a Golden Age 119

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

come to terms with the quality of the text. The words spoken by

Somerville’s little girls invoke the icon Elizabeth for whom all levels of

British society seemingly cherished some nostalgia. That this nostalgia

was mixed with genuine desire for a monarch capable of personally

generating a victory makes both the Prince Regent and his father dubious

candidates for uttering similar words in the current crisis. Small wonder

then, that the collective memory of Elizabeth emerged from the sphere

of the intangible and appeared, as it were, on every street corner.

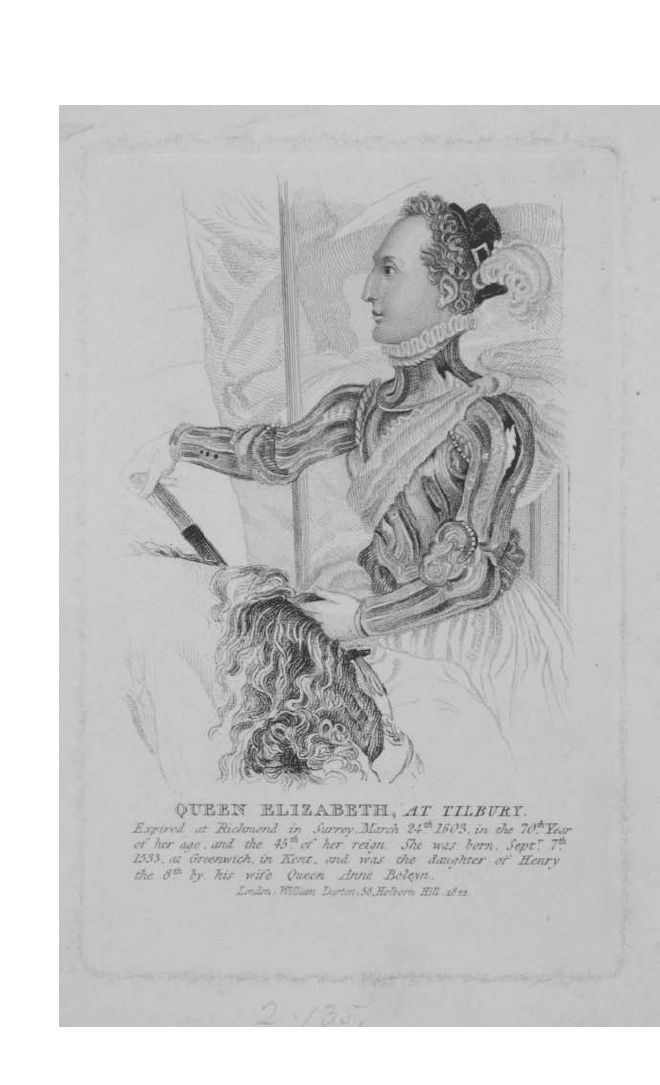

The print of Elizabeth at Tilbury (Figure 5) is a detail after (but not from)

an earlier print. This 1822 print by William Darton is copied after Thomas

Stothard’s 1805 larger print, which shows all of Elizabeth’s horse, one

bowing man in the foreground, soldiers before her and statesmen behind

her. Dobson and Watson discuss that version of the print, making the

important point that its vertical orientation speaks to the upright nature

of the British as they saw themselves in comparison to the French.

45

This

detail differs only a little from the Stothard print: Elizabeth’s forehead is

higher and the St. George Cross is more evident behind her than it is in

the busier, larger work. While containing its own blooper – the hair of

the man in Stothard’s foreground is tangled here with the horse’s mane

– the larger problem with the Stothard print is here unnoticeable. In the

large print the two flags in the background – the Royal Standard and the

St. George Cross – are being blown from right to left, while the ends of

the sash across Elizabeth’s bodice stream from left to right.

These details, of course, are quibbles. The point is that we have an

immediate and visual Elizabeth icon at just the time the island is once

again threatened from abroad. Dobson and Watson argue that this print

and much of the rhetoric of the times works to relocate the 1588 “broadly

… Protestant fiction” that “divine Providence had intervened to give the

English victory,” but that by the end of the eighteenth century, not only

was the emphasis being changed to suggest that “God had intervened

not so much on the side of Protestantism, but on the side of a nation’s”

liberty. “Indeed,’’ they conclude, “God was fast being edged out of the

story altogether.”

46

To support their reading of the times, Dobson and

Watson cite an impressive list of texts: Robert Southey’s 1798 Naucratia;

or Naval Domination; Robert Anderson’s 1805 “Britons, United, the World

May Defy”; and John Thelwall’s 1805 The Trident of Albion: an Epic Effusion.

These, along with Macauley’s poem “The Armada,” according to Dobson

and Watson, collectively construct “a fantasy which again links national

identity with the land rather than with religion.”

47

There is nothing in

these arguments with which anyone could seriously disagree, but there

might be one point that needs to be appended to the Dobson/Watson

120 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

1660–1837: The Shadow of a Golden Age 121

Figure 5 “Queen Elizabeth at Tilbury;” print by William Darton, 1822

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

analysis. The figure of Elizabeth herself the co-authors compare to the

Cecil print of Elizabeth receiving a lance from Truth (see Figure 2); but

– while such similarities as the queen mounted on a horse and wearing

garb that suggests armor are indisputable – I would suggest that this

Elizabeth icon (literally an icon in the detailed version) makes a very

different statement. In the Cecil print, Elizabeth is perched in an unlikely,

but effectively dominant pose upon the side of the horse; here she is

realistically riding sidesaddle. Other than the central figures of Elizabeth

and her horse, Cecil offers only Truth, the seven-headed beast beneath

the horse’s hooves, and the distant naval formation of the Armada.

Elizabeth is the only human and one of only two personages in the frame.

In the larger Stothard print, Elizabeth is surrounded by no fewer than

ten men. Furthermore, the nineteenth-century print shows static men,

but the queen apparently in motion, as witnessed by her flying scarf-like

adornment. The action here is ongoing, with the battle yet to be won,

but clearly to be won by Elizabeth, as the figures of the men defer to her

motion and remain stationary. In the more iconic Darton print, the

motion is even more pronounced. Queen Elizabeth is on her way, and

with a firm sense of purpose, the George Cross of England (not Britain)

waving behind her. Elizabeth in the Cecil print has already won her

battle. Both the cognoscenti who knew of the Cecil print and the people

who saw Elizabeth on a horse for the first time in Stothard’s or Darton’s

prints would be left with no doubt that this was a woman on a mission.

Even though Darton’s 1822 print came seven years after Waterloo, he still

pays homage to the spirit of the original print: a queen goes forth, para-

doxically alone in a crowd, to face a task that will save her nation.

122 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

1837–1910:

The Shadow of a

Paternalistic Queenship

Elizabeth and Victoria – a power packaged by a title

The age of Victoria, especially in a book on a female monarch, has the

potential to become that yet untraveled world whose margin fades forever

and forever as one writes. Mercifully, the general outlines of both the

history and the cultural climate of this period are essentially clear to the

general public. My focus, therefore, is not upon the specifics of events

that would parallel the Spanish Match, but rather upon characteristics

of the era that gave rise to new venues for making and using images of

Queen Elizabeth. Ironically, the most obvious point of comparison – two

unmarried young women being crowned as queens regnant – is rendered

largely unavailable by the circumstances of both the Hanoverian

succession and Victoria’s own background. The Protestant Reformation,

the militant Catholicism of Mary Tudor, the threat of England becoming

an annex of Spain through that queen’s marriage to an heir to a foreign

throne, even the undignified shadow cast over the House of Tudor by

Henry VIII’s infamous search for the womb that he could fill to his will

– all these circumstances constitute serious affairs of state on the stage

that the problematic heir, Elizabeth, must enter. Furthermore, before she

could claim the crown, Elizabeth had had to survive more political intrigue

and theological hair-splitting than Victoria ever had occasion to read

about, let alone experience. Elizabeth’s crowning was a triumph in itself;

her survival was an even greater achievement. In further contrast, the

excesses of the Regency, the bawdy court of William, the increasingly

messy tangles with Parliament, all combine to provide a smutty

background (literally smutty, too, with the amount of coal being burnt

123

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

in London) for the undisputed and welcome entrance of a fresh, young,

sheltered girl, arguably more German than English. And – despite sugges-

tions by Parliament that Victoria rule as Elizabeth II – the

nineteenth-century monarch actively rejected any comparison between

herself and Queen Elizabeth.

1

If Elizabeth had the heart and stomach of a king, Victoria had the heart

and stomach of a pater familias. That she came equipped with a hyper-

functional womb was a plus for the values she and her kinsman/consort

set out to establish. Just about the only things the two women did share

were the title and a strong sense of duty, for all that they would have

defined the latter quite differently. It is perhaps only a slight over-

simplification to say that Elizabeth was a woman grasping the opportunity

of power by the title she inherited, while Victoria imparted a fresh sig-

nificance – but quite another sort of power – to the title that she bore for

so very long. Being a queen allowed Elizabeth scope to exercise her

intellect, wit, and principles; being a woman of distinctly middle-class

values allowed Victoria the scope to redefine the role of queen.

Of all the riches in the span of Victoria’s reign, I’ve chosen two – the

Pre-Raphaelites and their imitators for high art and the humble biscuit

tin for low art. The literature of the period is, of course, rife with Elizabeth

references (if not fully delineated icons), from Kipling’s poem Gloriana,

to the first wave of what would become a sea of biographies, to rollicking

adventure novels, such as Lathom’s 1806 The Mysterious Freebooter; or The

Days of Queen Bess, and (to pick but one year) the 1897 pseudo-historical

narrative by Robert Haynes Cave, In the Days of Good Queen Bess: The

Narrative of Sir Adrian Trafford, Knight, of Trafford Place in the County of Suffolk

(London: Burns & Oates, Limited), and its feminine counterparts of the

same year: The Honor of a Princess: A Romance of the Time of “Good Queen

Bess” by F. Kimball Scribner, published in both London and New York,

and Lady Newdigate-Newdegate’s Gossip from a Muniment Room: Being

passages in the Lives of Anne and Mary Fytton 1574–1618. Despite all the

rich opportunities afforded by the literature – both high and low – of the

period, the visual arts are more fascinating. We are now getting to the

age of the mass-produced image, and that phenomenon merits close

scrutiny. While citizens of London or other large cities might have seen

portraits (or, more likely, prints) of Elizabeth’s image during the previous

three centuries, the nineteenth-century Briton could fairly easily acquire

either a print/engraving of a currently famous painting or a piece of

kitsch elevated (or at least made more attractive) by a royal image. Owning

an image is a tricky thing. One may be daily impressed and enlightened

by it – the purpose of all those saints’ icons littering the middle ages –

124 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

but one may also learn to take it for granted. Hamlet says that the greatness

that was Alexander may have become loam with which to stop a beer

barrel. But even that doesn’t have the pedestrian immediacy of keeping

one’s pennies in a tin decorated with the face of a queen. Familiarity –

here meaning cozy comfort – may not always breed contempt, but it

generally does dispel awe.

And, for all its industrial, social, and cultural advances, a key phrase

for the Victorian era would have to be “familiarity.” Traced through

Middle English and Old French to Latin, the word of course derives from

the word for “family.” Yes, in the big-picture sense, this was the time that

Britons became familiar with the world. But literal family values, figured

forth by the relentlessly middle-class royal family (surely one of the few

examples in history of people aspiring to move down the social ladder)

and by the family values we have now come to call, pejoratively,

“Victorian,” were a point of exchange for both national and individual

identity. The public sphere of memory expunged such unpleasantnesses

as the American Revolution, and instead celebrated tobacco as England’s

gift to the world; the problematic history of circumnavigation of the

globe was revised over a reviving cup of tea, the new national drink. The

Empire replaced – or expanded – the England of which the queen was a

mother. The building of personal fortunes in trade, railways, or importing,

established pseudo-dynasties of wealth and power. The venerated construct

of the family may have been for some a reality or a realistic goal; but for

most of Britain it was at once a charming façade masking many sorts of

dark doings, and a century-long son et lumière of sufficient proportions

to distract all but the most fanatical reformers from the many sores on

the body politic. As an example of high art spectacle, the paintings of

the Pre-Raphaelites rendered sadly pointless stories (Ophelia and Elaine,

the maid of Shallot) as pretty tableaux (still, to the despair of faculty

members, lovingly displayed on the walls of undergraduates’ rooms) and

real tragedies (Cordelia and Joan of Arc) as – yet again – tableaux in which

the sensual beauty of a flower-strewn stream, a gown, a tapestry, a woman’s

hair, a rose, calls forth a stronger reaction than the allusion to a stupidly

passive drowning or a death by flame, not flower petals.

At the other end of the family-culture spectrum, exemplifying the

façade of the wholesome family, we find the biscuit tin. Occupying an

awkward site between the utilitarian and the decorative, the biscuit tin

and its cousins (tea, toffee, tobacco) could be found in every archetyp-

ally Victorian home. Gifted with the near-assurance of a utilitarian

resurrection, the container went from its initial function on to any number

of reincarnations. Indeed, the companies making the tins did so with an

1837–1910: The Shadow of a Paternalistic Queenship 125

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

eye for yet another Victorian trait: collecting for the sake of collecting.

Made in the shapes of books or baskets, decorated with English historical

scenes or oriental fantasies, with flowers or faces, the boxes themselves

became objects that generated the acquisitive instincts of those Victorians

occupying houses filled with curio cases, elaborate display shelves, multiple

decorative tables, all governed by the unspoken commandment: thou shalt

leave no surface bare. As an inverse reaction to the vast swaths of land

and sea ruled by Britannia, the Victorian home was allowed to have no

empty spaces. More was more. (Or, as Mae West so wonderfully said in

quite a different context: “too much of a good thing is wonderful.”)

c.1867: a domestic empire – monarchy and the biscuit tin

The fashion for decorative tins sprang up in the second half of the

nineteenth century. The English tin, popularly called a biscuit tin, is

surely an exquisite example of bringing an exalted object to a humble

subject. The object itself – the tin – is, of course, of very little value. But

a tin with the face of Queen Victoria on it generates interest, amazement,

or the desire to acquire it, depending upon the character of the customer.

There were many types of decorated tins: mustard, cocoa, washing powder,

tobacco, baking powder, and syrup are a few that spring immediately to

mind. Tea tins are indeed called tea tins, but, “biscuit” remains a generic

designation from Southebys to the Victoria & Albert to eBay, despite the

rantings of experts such as M. J. Franklin:

At present, all tin boxes seem to be given the misnomer of “biscuit tins”.

One of the major London salesrooms not long ago announced their

first ever sale of tins as “A Collection of Biscuit Tins”, when in fact about

half of the items were tins that had never contained biscuits. A biscuit

tin is a biscuit tin; a sweet in a tin that contained sweets, likewise tins

for tea, mustard, etc. For some reason, tea and sweet manufacturers

often did not put the name of the firm on the tin, so it is under-

standable that this can only be guessed at and so can only be called

“tins”, but the author has yet to find a British biscuit tin which does

not make mention somewhere on the tin of a biscuitmaker’s name.

Without such a mark it should not be called a biscuit tin.

2

While respecting Mr. Franklin’s expertise and apologizing to his sensi-

bilities, I will continue to refer to almost all of the tins in this chapter as

biscuit tins. The first tin, for example, is one of the earliest to be decorated

with a royal image, and it is, in fact, a mustard tin. Moss Rimmington

and Company sold this tin (Figure 6) around 1868. The subject of the

126 The Elizabeth Icon, 1603–2003

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-24

Figure 6 Princess Alexandra in her boudoir at Sandringham. Moss Rimmington and Co., c.1868. Collection of the author

127

10.1057/9780230288836 - The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003, Julia M. Walker

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect -

2011-03-24