Walker J. Facies models, Canada, 1992

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

INTRODUCTION

A delta is a discrete shoreline protuber-

ance formed at a point where a river

enters an ocean or other large body of

water. Many deltas cover a large area,

and have been influenced by a variety

of

fluvial and marine processes. Sev-

eral distinct sub-environments of de

position can therefore be identified

within a delta. This makes it difficult or

impossible to characterize an ancient

deposit as "deltaic" simply on the basis

of a single core or outcrop section; a

restored plan view of the system is

necessary. Ancient deltas are eco

nomically important because they are

commonly associated with major coal,

oil and gas reserves. As a result,

deltas have been intensively studied,

and deltaic facies models have become

relatively well established. Readers are

referred to several recent summaries for

general information (Colella and Prior,

1990; Whateley and Pickering, 1989;

Elliott, 1986;

Miall, 1984; Coleman and

Prior, 1982; Broussard, 1975).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The concept of a delta dates back to

the time of Herodotus (ca. 400 B.C.)

who recognized that the alluvial plain

at the mouth of the Nile had the form

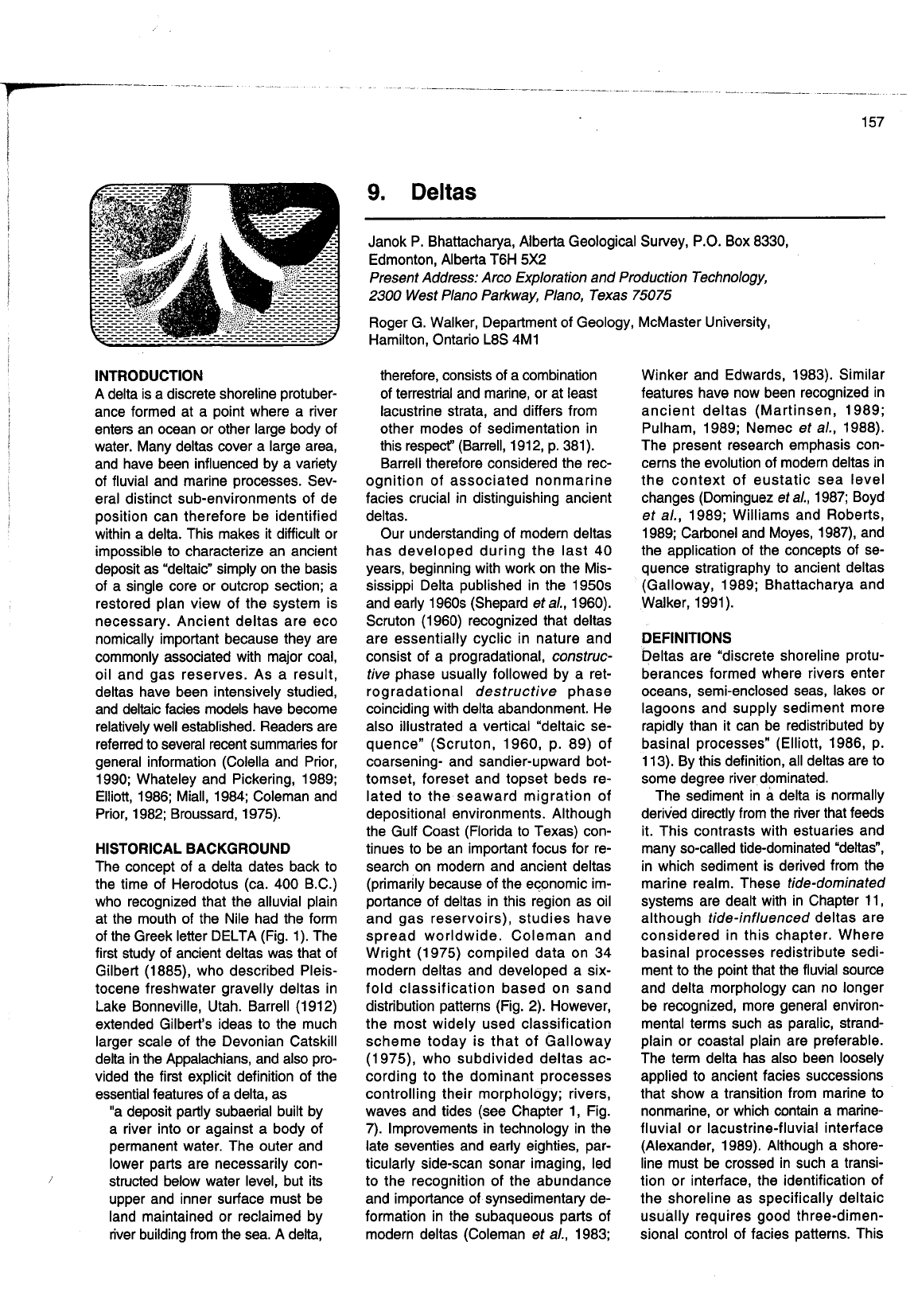

of the Greek letter DELTA (Fig. 1). The

first study of ancient deltas was that of

Gilbert

(1885), who described Pleis-

tocene freshwater gravelly deltas in

Lake Bonneville, Utah. Barrell (1912)

extended Gilbert's ideas to the much

larger scale of the Devonian

Catskill

delta in the Appalachians, and also pro-

vided the first explicit definition of the

essential features of a delta, as

"a deposit partly subaerial built by

a river into or against a body of

permanent water. The outer and

lower parts are necessarily con-

structed below water level, but its

upper and inner surface must be

land maintained or reclaimed by

river building from the sea. A delta,

9.

Deltas

Janok P. Bhattacharya, Alberta Geological Survey, P.O. Box 8330,

Edmonton, Alberta T6H

5x2

Present Address: Arco Exploration and Production Technology,

2300 West Plano Parkway, Plano, Texas 75075

Roger G. Walker, Department of Geology,

McMaster University,

Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4M1

therefore, consists of a combination

of terrestrial and marine, or at least

lacustrine strata, and differs from

other modes of sedimentation in

this

respecf' (Barrell, 191 2, p. 381).

Barrell therefore considered the rec-

ognition of associated nonmarine

facies crucial in distinguishing ancient

deltas.

Our understanding of modern deltas

has developed during the last 40

years, beginning with work on the Mis-

sissippi Delta published in the 1950s

and early 1960s

(Shepard et a/., 1960).

Scruton (1 960) recognized that deltas

are essentially cyclic in nature and

consist of a progradational, construc-

tive phase usually followed by a

ret-

rogradational destructive phase

coinciding with delta abandonment. He

also illustrated a vertical "deltaic se-

quence" (Scruton, 1960, p. 89) of

coarsening- and sandier-upward

bot-

tomset, foreset and topset beds re-

lated to the seaward migration of

depositional environments. Although

the Gulf Coast (Florida to Texas) con-

tinues to be an important focus for re-

search on modern and ancient deltas

(primarily because of the economic im-

portance of deltas in this region as oil

and gas reservoirs), studies have

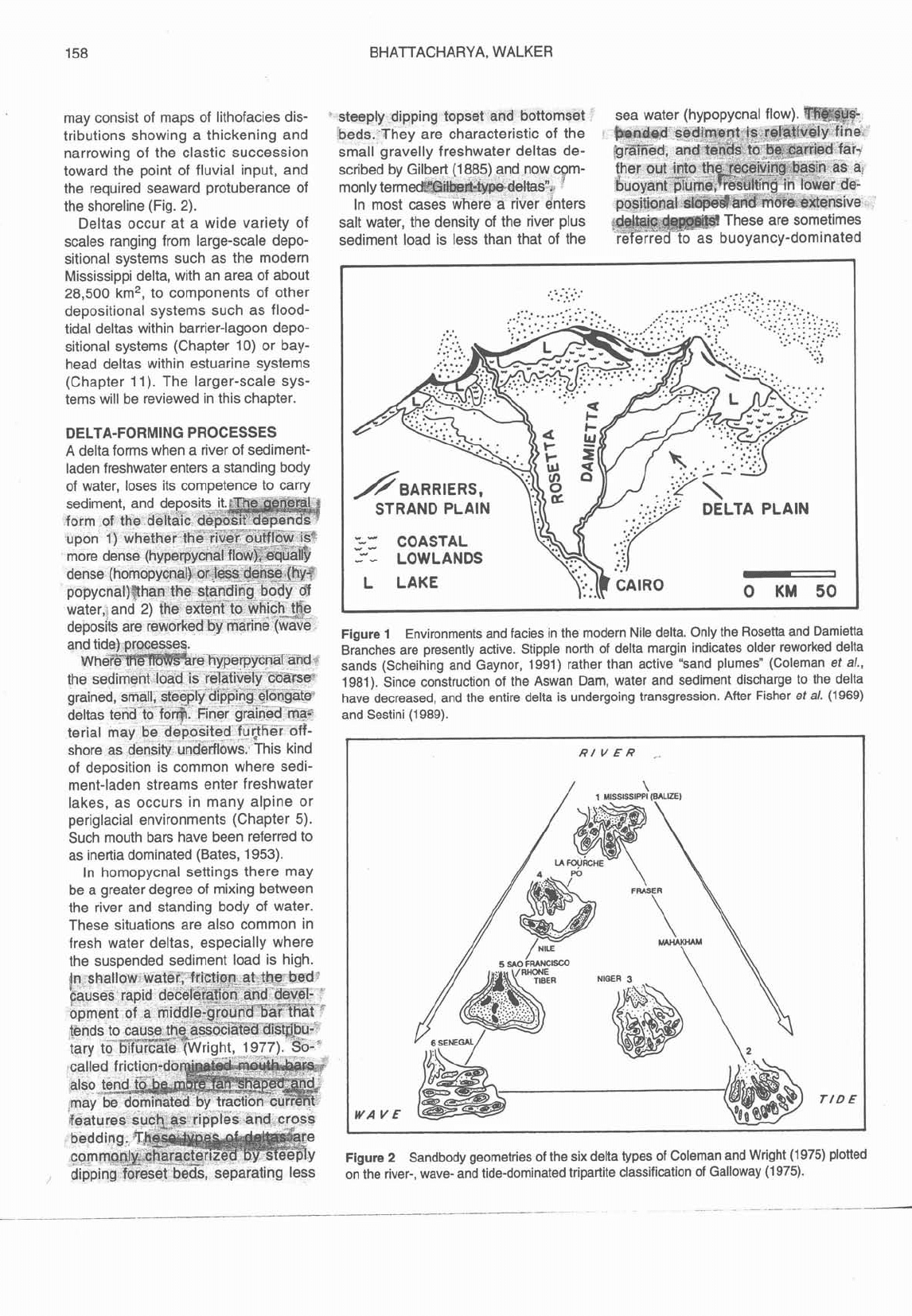

spread worldwide. Coleman and

Wright (1975) compiled data on 34

modern deltas and developed a six-

fold classification based on sand

distribution patterns (Fig. 2). However,

the most widely used classification

scheme today is that of

Galloway

(1 975), who subdivided deltas ac-

cording to the dominant processes

controlling their morphology; rivers,

waves and tides (see Chapter 1, Fig.

7). Improvements in technology in the

late seventies and early eighties, par-

ticularly side-scan sonar imaging, led

to the recognition of the abundance

and importance of synsedimentary de-

formation in the subaqueous parts of

modern deltas (Coleman et

a/., 1983;

Winker and Edwards, 1983). Similar

features have now been recognized in

ancient deltas (Martinsen, 1989;

Pulham, 1989; Nemec et al., 1988).

The present research emphasis con-

cerns the evolution of modern deltas in

the context of eustatic sea level

changes (Dominguez etal., 1987; Boyd

et al., 1989; Williams and Roberts,

1989;

Carbonel and Moyes, 1987), and

the application of the concepts of se-

quence stratigraphy to ancient deltas

(Galloway, 1989; Bhattacharya and

Walker, 1991).

DEFINITIONS

Deltas are "discrete shoreline protu-

berances formed where rivers enter

oceans, semi-enclosed seas, lakes or

lagoons and supply sediment more

rapidly than it can be redistributed by

basinal processes" (Elliott, 1986, p.

113). By this definition, all deltas are to

some degree river dominated.

The sediment in

a

delta is normally

derived directly from the river that feeds

it. This contrasts with estuaries and

many so-called tide-dominated "deltas",

in which sediment is derived from the

marine realm. These tide-dominated

systems are dealt with in Chapter 11,

although tide-influenced deltas are

considered in this chapter. Where

basinal processes redistribute sedi-

ment to the point that the

fluvial source

and delta morphology can no longer

be recognized, more general environ-

mental terms such as paralic,

strand-

plain or coastal plain are preferable.

The term delta has also been loosely

applied to ancient facies successions

that show a transition from marine to

nonmarine, or which contain a

marine-

fluvial or lacustrine-fluvial interface

(Alexander, 1989). Although a shore-

line must be crossed in such a transi-

tion or interface, the identification of

the shoreline as specifically deltaic

usually requires good three-dimen-

sional control of facies patterns. This

158 BHATTACHARYA, WALKER

may consist of maps of lithofacies dis-

tributions showing a thickening and

narrowing of the

clastic succession

toward the point of

fluvial input, and

the required seaward protuberance of

the shoreline (Fig.

2).

Deltas occur at a wide variety of

scales ranging from large-scale depo-

sitional systems such as the modern

Mississippi delta, with an area of about

28,500

km2, to components of other

depositional systems such as flood-

tidal deltas within barrier-lagoon depo-

sitional systems (Chapter 10) or bay-

head deltas within estuarine systems

(Chapter 11). The larger-scale sys-

tems will be reviewed in this chapter.

DELTA-FORMING PROCESSES

A delta forms when a river of sediment-

laden freshwater enters a standing body

of water, loses its competence to carry

sediment, and

deposits_:-

form of the deltaic dep

upon 1) whether the river outflow is"

more dense (hyperpycnal flow),

equal@

dense (homopycnal) or less dense (hyB

popycnal)?than the standing body oY

water; and

2)

the extent to whickt5e

deposits are reworked by marine (wave

re

Tiyperp)fBnaT

aid

*

s relatively

"carst?

grained, small, steeply dipping elongatea

deltas tend to'forfi. Finer grained ma-*

terial may be deposited fucther off-

shore as density underflows. This kind

of deposition is common where sedi-

ment-laden streams enter freshwater

lakes, as occurs in many alpine or

periglacial environments (Chapter

5).

Such mouth bars have been referred to

as inertia dominated (Bates, 1953).

In homopycnal settings there may

be a greater degree of mixing between

the river and standing body of water.

These situations are also common in

fresh water deltas, especially where

the suspended sediment load is high.

In shallow.

watei:Trimim-.at:th~33d*

fdauses rapid decderationand devel--r

opment of a middle-ground

bGe1hat-"

tends

-

to

-

-

cause

wa..a3-r

the=associated distdbu-"

tary to bifurcate (Wright, 1977). So-"

called friction-dogmb&ad

also

)el?,dG&&&~~l~~a~~fia~p~~g.a~,dd

,may be dominated by traction curreiit

steeply dipping topset and bottomset

sea water (hypopycnal flow).

beds. They are characteristic of the

~n~'Jd'sedl"m@rrtd~s!rCj~~f~fvely

fine;

small gravelly freshwater deltas de-

igralfied, and rends to be, carried far-

scribed by Gilbert (1885) and now

cgm-

ther out into the receiving basin as a!

monly

termeflfibe78-ty.ps.Cfelhs"7;

'

buoyant ~jlurne,~esultin~ in lower de-

In most cases where a river enters

positional

slopegand more extensive

salt water, the density of the river plus

(deltaic

dWaPits!

These are sometimes

sediment load is less than that of the

referred to as buoyancy-dominated

..

-

.

.

.

'

.

:

.'.'

....

STRAND PLAIN DELTA PLAIN

",

w

=-

COASTAL

---

LOWLANDS

L LAKE

-

0

KM

50

Figure

1

Environments and facies in the modern Nile delta. Only the Rosetta and Damietta

Branches are presently active. Stipple north of delta margin indicates older reworked delta

sands (Scheihing and

Gaynor, 1991) rather than active "sand plumes" (Coleman

et

a/.,

1981). Since construction of the Aswan Dam, water and sediment discharge to the delta

have decreased, and the entire delta is undergoing transgression. After Fisher

et a/.

(1969)

and Sestini (1989).

WAVE

-,.""

5

SO

FRANCISCO

/RHONE

!d%\

Tl8ER NIGER

3

-.

Figure 2

Sandbody geometries of the six delta types of Coleman and Wright (1975) plotted

on the river-, wave- and tide-dominated tripartite classification of

Galloway (1975).

9. DELTAS

mouth bars. In any given river mouth or

river mouth sediments (Martinsen,

delta, inertial, frictional, and buoyant

1990;

Pulham, 1989; Harris, 1989).

forces may be operative in varying

pro-

Deltas comprise three main subenvir-

portions. Recent work has attempted to

onments;

theWta:ptai~ (where river

distinguish the relative importance of

processes dominate),

dwdelta

from

these processes in classifying ancient

(where river and basinal processes are

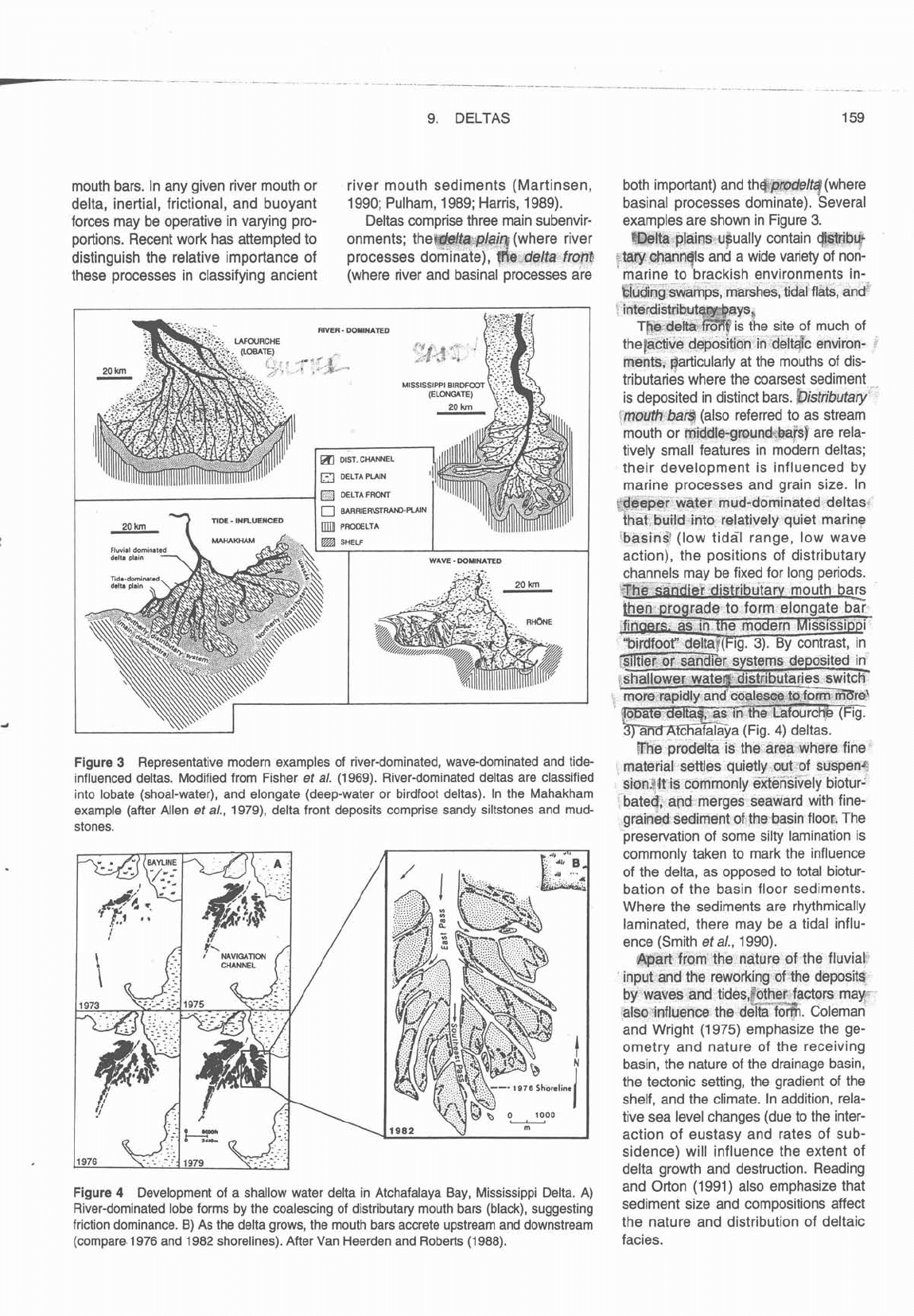

Figure

3

Representative modern examples of river-dominated, wave-dominated and tide-

influenced deltas. Modified from Fisher

et

a/.

(1969). River-dominated deltas are classified

into

lobate (shoal-water), and elongate (deep-water or birdfoot deltas). In the Mahakham

example (after Allen

et

a/.,

1979), delta front deposits comprise sandy siltstones and mud-

stones.

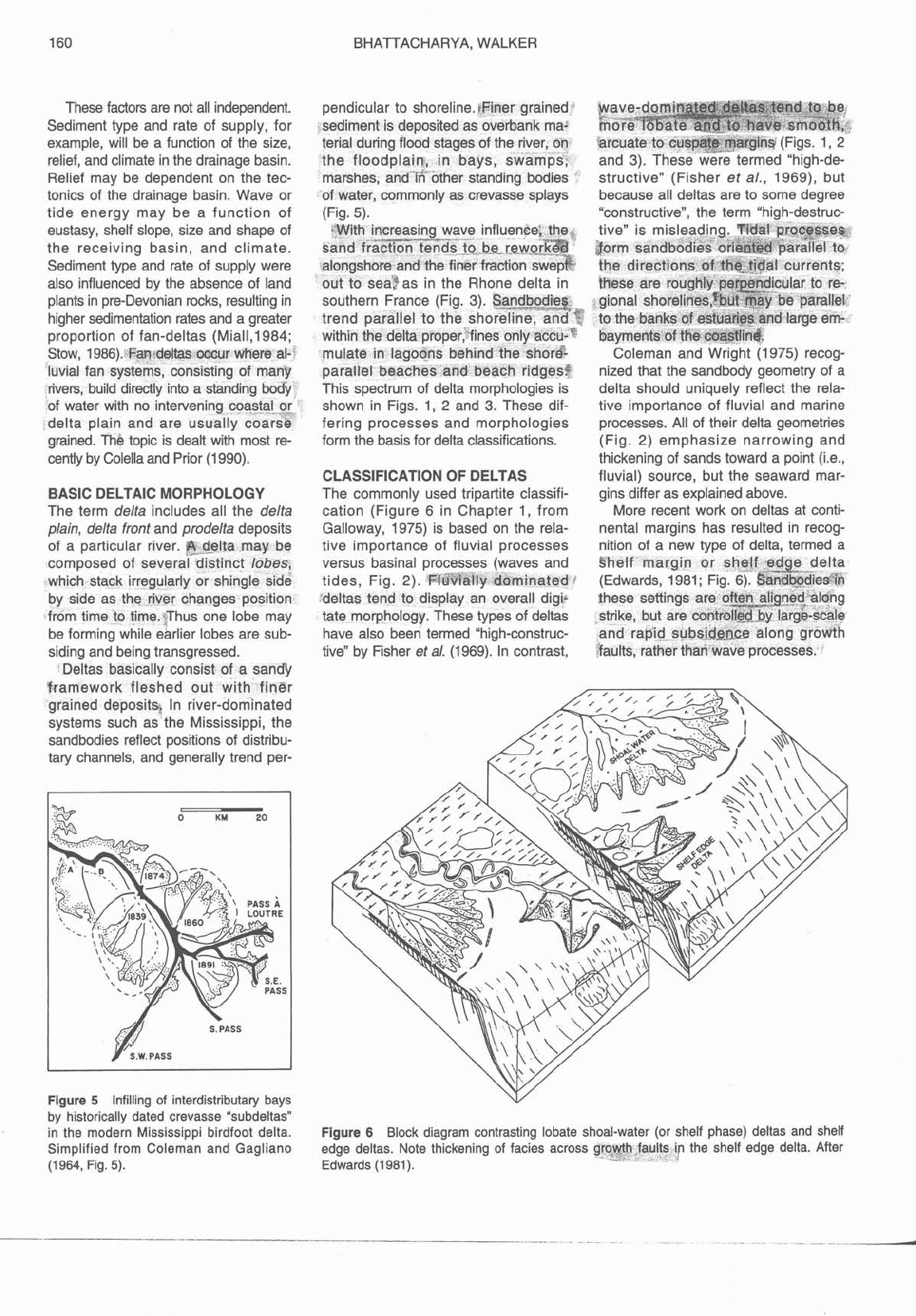

Figure

4

Development of a shallow water delta in Atchafalaya Bay, Mississippi Delta. A)

River-dominated lobe forms by the coalescing of distributary mouth bars (black), suggesting

friction dominance.

0)

As the delta grows, the mouth bars accrete upstream and downstream

(compare. 1976 and 1982 shorelines). After Van Heerden and Roberts

(1

988).

both important) and

th@p&delt~(where

basinal processes dominate). several

examples are shown in Figure

3.

Qlelta plains+ulually contain @Rib@

*@ry

channt$ls and a wide variety of non-

marine to brackish environments in-.

biuding\swamps, marshes, tidal flats, an&

!

interdistributa@?hs1ys,

Tpe delta

f?%$

is the site of much of

thefactive deposition in deltc environ-

;

rnents, particularly at the mouths of dis-

tributaries where the coarsest sediment

*-

is deposited in distinct bars.

Distributay

fm~uth

baa

(also referred to as stream

mouth or

middle-groundbbaisj are rela-

tively small features in modern deltas;

their development is influenced by

marine processes and grain size. In

Pdbeper water mud-dominated deltas-

that build into relatively quiet marine

basins (low tidal range, low wave

action), the positions of distributary

channels may be fixed for long periods.

LThg sandier distributarv mouth bars

!hen prograde to form elongate be

,finaers. as in the modern Mississippi

"birdfoot"

delta;(Fig.

3).

By contrast, in

Fsiltier or sandier systems deposited in

shallower waterj distributaries switch

,

'more rapidly and coalesce to fomrel

ToDate deltas. as76the Lafourche

(Fx

.

-

$Zid74t~haf~la~a (Fig.

4)

deltas.

The prodelta is the area where fine

1

material settles quietly out 'of SUSjEn*

sionblt is commonly extensively biotur-

bated,

and merges seaward with fine-

grained sediment of the basin floor& The

preservation of some silty lamination is

commonly taken to mark the influence

of the delta, as opposed to total biotur-

bation of the basin floor sediments.

Where the sediments are rhythmically

laminated, there may be a tidal influ-

ence (Smith

eta/.,

1990).

Rpart from the nature of the fluvial-

input and the reworking of the deposits

by waves and

tides,Fothet factors may-

-

-

also influence the deita form. Coleman

and Wright (1975) emphasize the ge-

ometry and nature of the receiving

basin, the nature of the drainage basin,

the tectonic setting, the gradient of the

shelf, and the climate. In addition, rela-

tive sea level changes (due to the inter-

action of eustasy and rates of sub-

sidence) will influence the extent of

delta growth and destruction. Reading

and

Orton (1991) also emphasize that

sediment size and compositions affect

the nature and distribution of deltaic

facies.

BHAlTACHARYA, WALKER

These factors are not all independent.

Sediment type and rate of supply, for

example, will be a function of the size,

relief, and climate in the drainage basin.

Relief may be dependent on the tec-

tonics of the drainage basin. Wave or

tide energy may be a function of

eustasy, shelf slope, size and shape of

the receiving basin, and climate.

Sediment type and rate of supply were

also influenced by the absence of land

plants in pre-Devonian rocks, resulting in

higher sedimentation rates and a greater

proportion of fan-deltas

(Mia11,1984;

Stow, 1986).i:Fan~deltas mur where al-'

luvial fan systems, consisting of many

rivers, build directly into a standing body,

of water with no intervening coastal-or,

delta plain and are usually coarse

grained.

ThB topic is dealt with most re-

cently by

Colella and Prior (1 990).

BASIC DELTAIC MORPHOLOGY

The term

delta

includes all the

delta

plain, delta front

and

prodelta

deposits

of a particular river.

R

delta may be

composed of

severai~distinct

lobes,

which stack irregularly or shingle side

by side as the river changes position-

from time to

time.iThus one lobe may

be forming while earlier lobes are sub-

siding and being transgressed.

Deltas basically consist of a

sanm

Tramework fleshed out with finer

grained deposits In river-dominated

systems such as the Mississippi, the

sandbodies reflect positions of distribu-

tary channels, and generally trend per-

pendicular to shoreline.

tFiner grained

!~vave-domi~ppaP4CSt.~tY

...*-

m.--

.

fo-be

sediment is deposited as overbank ma- moredb%ate and to have smooth;

terial during flood stages of the river, on

the floodplain', in bays, swamps,

marshes, and

?n

-other standing bodies

'

of water, commonly as crevasse splays

(Fig. 5).

~"W[th increasing wave influenee: thea.

'sand fra-eTds to,

b-e.-

~e.worm

-alonqshore and the fi&r fraction swep@

out to sea7as in the Rhone delta in

southern France (Fig.

3).

Sa~~ochs,

trend parallel to the shoreline,

in";1"?

within the delta properrfines only accu-'

mulate in lagoons behind the shod

parallel beaches and beach ridges?"

This spectrum of delta morphologies is

shown in Figs.

1,

2

and

3.

These dif-

fering processes and morphologies

form the basis for delta classifications.

CLASSIFICATION OF DELTAS

The commonly used tripartite classifi-

cation (Figure 6 in Chapter 1, from

Galloway, 1975) is based on the rela-

tive importance of

fluvial processes

versus basinal processes (waves and

tides, Fig.

2).

FlbVIaily dominated

f

:deltas tend to display an overall digis

tate morphology. These types of deltas

have also been termed "high-construc-

tive" by Fisher

et a/.

(1 969). In contrast,

Uarcuate to cuspate margins (Figs. 1,

2

and

3).

These were termed "high-de-

structive" (Fisher

et al.,

1969), but

because all deltas are to some degree

"constructive", the term "high-destruc-

tive" is misleading.

Wdal

prtrcesses*

goform sandbbdies ohhnfed parallel to

the directions of the tidal currents;

Yhese are roughly

pepzndicular to re-

/

gional shorelines,fbut may be parallel'

to the banks of estuaries and large em-

bayments of

th$ coastline!.

Coleman and Wright (1975) recog-

nized that the

sandbody geometry of a

delta should uniquely reflect the rela-

tive importance of

fluvial and marine

processes. All of their delta geometries

(Fig.

2)

emphasize narrowing and

thickening of sands toward a point

(i.e.,

fluvial) source, but the seaward mar-

gins differ as explained above.

More recent work on deltas at conti-

nental margins has resulted in recog-

nition of a new type of delta, termed a

!%elf margin or shelf ,edge delta

-

."--

(Edwards, 1981

;

Fig.

6).

Sandbodiesri'n

these seftings are

ofttn__aligned

along

,strike, but are controlled

-by large-scale

and

rap'id _subsidence along growth

'faults, rather than wave processes.

,

Figure

5

Infilling of interdistributary bays

by historically dated crevasse "subdeltas"

in the modern Mississippi

birdfoot delta.

Figure

6

Block diagram contrasting lobate shoal-water (or shelf phase) deltas and shelf

Simplified from Coleman and Gagliano

edge deltas. Note thickening of facies across

growth faults

i~

the shelf edge delta. After

(1964,

Fig.

5).

Edwards

(1

981).

FACIES SUCCESSIONS WITHIN

DELTAIC DEPOSITIONAL SYSTEMS

In addition to

sandbody geometries,

Coleman and Wright (1975) presented

a series of composite vertical facies

successions through the prodelta, del-

ta front and delta plain environments

of each of their delta types. Idealized

facies successions represent "norms",

and may be very useful points of refer-

ence for outcrop studies where three-

dimensional control may be limited,

but, as with all norms, they should not

be used unthinkingly. Typical facies

successions through the dominantly

marine (prodelta and delta front) and

dominantly nonmarine (delta plain)

parts of deltas, mostly in river- and

wave-dominated settings, are outlined

below.

Prodelta and delta front

successions

@?Tatlation of a delta bbe will tend to2

pmduce a single, relatively thick coaTd-

bning-upward facies successior? (Fig. 7)

Bhowing a transition from muddie

fhcies of-the piodelta into the sandier

9. DELTAS 161

Vacies ot the deltX front and mouth bar

environments

(Elliott, 1986; Coleman

and Wright, 1975). Thicknesses may

range from a few metres to a hundred

metres depending on the scale of the

delta and the water

depth.'ContTTued

progradation may result in delta plais

facies ovPHyiRg the delta frcmtsands in.

a continuous

succession.~6VV(?ver, cTel-

*

?a front sands may be-partially eroded*

by-progradation of the

distributarp

channel over its own mouth bar (Fig.

7).

Commonly, progradational delta lobe

3

successions are truncated

by

thin trans-s

bressive aband6nh"eX-~k5~Wg.

8).

In shelf edge deltas .fFig. 6), thick

coar~;i~g-~~pwafidelta fiont succa

isions are commonly completely pre-

9

Served in thicker depzsils across thd

'seaward downthrown portion of growth*

e

faults!%h=4he ghatlower landward pofi

tions, greater reworking by shalTow-"

marine processes can result in mars

complex facies successions=(Winker

and Edwards, 1983).

The specific nature of the facies in

prograding

prodelta and delta front

successions will depend on the

pro-

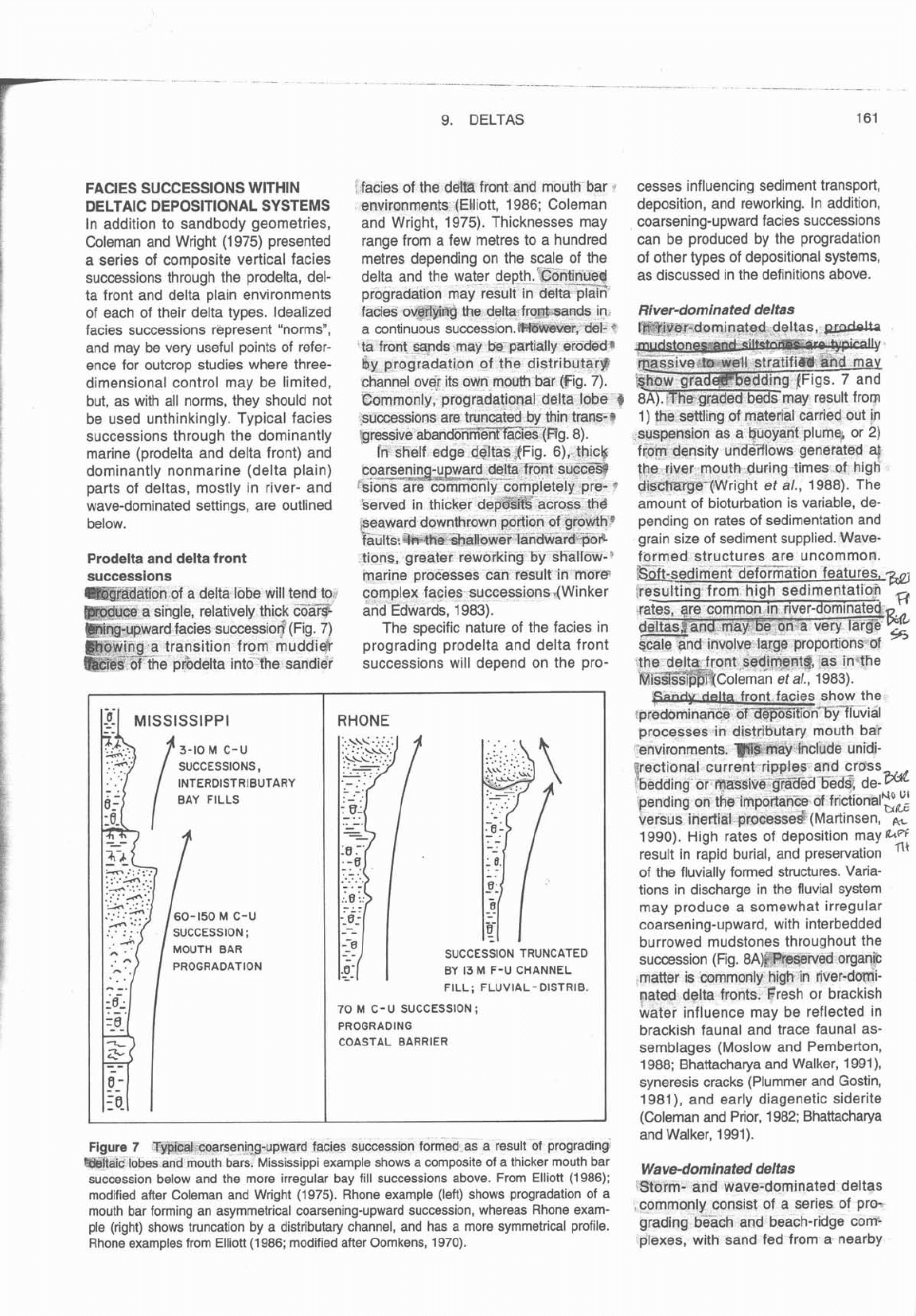

Figure

7

Tfiidal

.coarsening-upward facies succession formed as a result of prograding

mltaic lobes and mouth bars. Mississippi example shows a composite of a thicker mouth bar

succession below and the more irregular bay fill successions above. From Elliott (1986);

modified after Coleman and Wright (1975). Rhone example (left) shows progradation of a

mouth bar forming an asymmetrical coarsening-upward succession, whereas Rhone exam-

ple (right) shows truncation by a distributary channel, and has a more symmetrical profile.

Rhone examples from Elliott (1986; modified after Oomkens, 1970).

RHONE

60-150

M

C-U

MOUTH

BAR

SUCCESSION

TRUNCATED

PROGRADATION

BY

13

M

F-U

CHANNEL

cesses influencing sediment transport,

deposition, and reworking. In addition,

coarsening-upward facies successions

can be produced by the progradation

of other types of depositional systems,

as discussed in the definitions above.

-

-.

.

-

re:

.

-.

=

0

-

-

-

-

-

0

-

-

-

f

e

River-dominated deltas

rfTiQb~dorninated deltas,

&mddia

w%

massive to well stratified and may

ishow gradebedding (F~gs. 7 and

$A). The graded beds may result from

I) the settling of material carried out in

suspension as

a

buoyant plume& or

2)

from density undeiflows generated

aJ

the river mouth- during times of high

dibchBrge*'(Wright

et a/.,

1988). The

amount of bioturbation is variable, de-

pending on rates of sedimentation and

grain size of sediment supplied.

Wave-

formed structures are uncommon.

FILL;

FLUVIAL-DISTRIB.

70

M

C-

U

SUCCESSION

;

PROGRADING

COASTAL BARRIER

&edimeri~d6foriafion features,

bresultina from hiah sedimentation

,

"

"

rates, are common in river-dominated-

deltas,; and may"

b-e on 'a very large

&

scale and involve large proportions of

55

'the delta;-front sediment$, as in 'the

Missssippi TColeman

eta/.,

1983).

front facies show the

'predominance of

dE~osition""by7luvial

processes in distributary mouth bar

environments.

v5

may include unidi-

frectional current ripples and cross

"bedding or

~ssive gratfed-6e6; de-w

pending on the importance of

frictional^^

versus inertial processed (Martinsen,

1990). High rates of deposition may

result in rapid burial, and preservation

-nt

of the fluvially formed structures. Varia-

tions in discharge in the

fluvial system

may produce a somewhat irregular

coarsening-upward, with interbedded

burrowed mudstones throughout the

succession (Fig.

8A)f~SWed organit

,matter is commonly high in river-dmi-

nated delta fronts.-Fresh or brackish

water influence may be reflected in

brackish faunal and trace faunal as-

semblages (Moslow and Pemberton,

1 988; Bhattacharya and Walker,

1

991),

syneresis cracks (Plurnmer and Gostin,

1981), and early diagenetic siderite

(Coleman and Prior, 1982; Bhattacharya

and Walker, 1991

).

Wave-dominated deltas

*Storm- and wave~dominated deltas

,commonly consist of a series of

pro-

grading beach and beach-ridge cow-

plexes, with sand fed from a nearby

162

BHATTACHARYA, WALKER

[A

FLUVIAL

-

DOMINATED WAVE

-

INFLUENCED WAVE

-

DOMINATED

I

offshore

m

-

shslrf

I

m

o

B

FACIES

LEGEND

LITHOLOGY

SEDIMENTARY

STRUCTURES

Fin. -Medium

Sondrtone

4

HCSlSCS

~~Jg,~e

-

wove

ripples

sandy ~~d~l~~~ Currenl

ripples

~~,j~t~~

-#b

Cl+mbh9 rlPPl**

ShaleIMudstme

\-

Croasbeddlng

-

-,5

-

Shole/Mudrtrme closta Slgmolds

CD

Siderite

-

flat laminoled

3-5

Shell debrla

&&

Oversteepened

,

:~;rq~noceoua Loadlnp

II

Cool

*u

Graded beds

5

1

Syneresis

FOSSILS

4

hoc8romu1

1

Roots

@

flah remolns

@

oyster

0

0

Burrows

U

Pervoalve

&

Corbula

blolurbotion

Z

zoopnvcor

Q

LI~VUIO

g

relchlchnus

Brochydomer

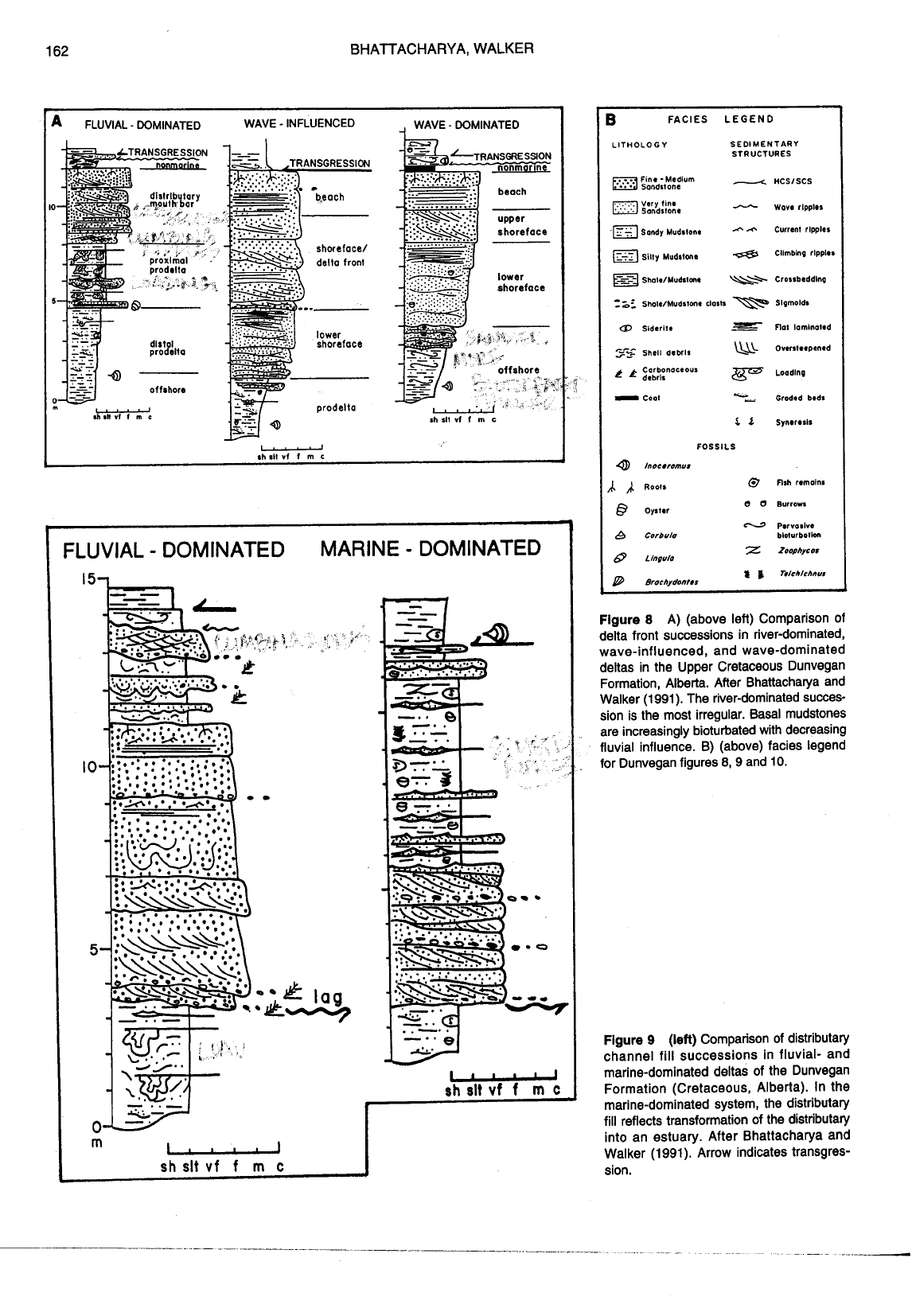

Flgure

8

A) (above left) Comparison of

delta front successions in river-dominated,

wave-influenced, and wave-dominated

deltas in the Upper Cretaceous

Dunvegan

Formation, Alberta. After Bhattacharya and

Walker (1991). The river-dominated succes-

sion is the most irregular. Basal mudstones

are increasingly bioturbated with decreasing

fluvial influence. B) (above) facies legend

.

for Dunvegan figures 8,9 and

10.

Figure

9

(left) Comparison of distributary

channel fill successions in

fluvial- and

marine-dominated deltas of the

Dunvegan

Formation (Cretaceous, Alberta). In the

marine-dominated system, the distributary

fill reflects transformation of the distributary

into an estuary. After Bhattacharya and

Walker (1991). Arrow indicates transgres-

sion.

-----

-

-

-

-.

.

-.

.

-

-

--

..

_.

. ._

-

_..

9. DELTAS 163

river

(e.g., Rhone).

$qe

delta 'front-!

Tide-influenced deltas

t

r&mWh@~anl1'B~~thef

%iBs

reflem

(Figs.

7

and

8

[wave-dominated

Tidally influenced prograding delta

"tidal influence.

smith

et

a/.

(1990) de-

column])

Ps

~lsually characterized by"a

fronts, such as the Fraser in Canada,

scribe tidal

rhythmites (see Chapter ll)

&Eati-wsly

continuous coarsenine

the Mahakham in Indonesia, and the

in glacio-marine

prodelta sediments in

-<.,%i%rA%.=-.

-,

IJpwZiFa-s success~on character-

Niger in Africa, also show an overall

Alaska and suggest that similar pro-

[stic of a wave-dominated shoreface

$

(Chapter

12).

The proportion of wave-

,

i

thin irregular cycles and overall increase in

proportion of nonmarine facies upward.

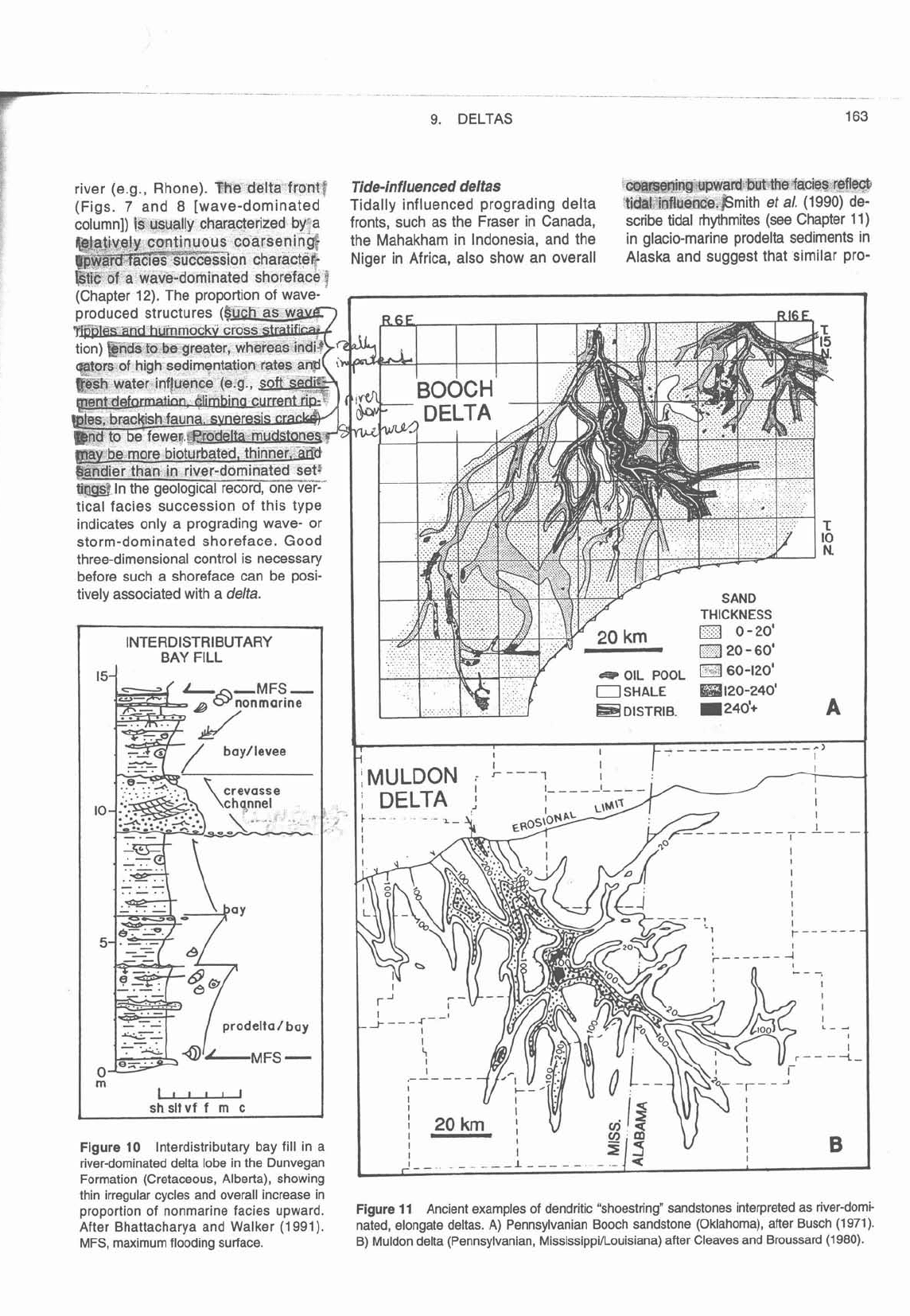

Figure

11

Ancient examples of dendritic "shoestring" sandstones interpreted as river-dorni-

After Bhattacharya and Walker (1 991).

nated, elongate deltas. A) Pennsylvanian

Booch sandstone (Oklahoma), after Busch (1971).

MFS, maximum flooding surface.

B)

Muldon delta (Pennsylvanian, Mississippi/Louisiana) after Cleaves and Broussard (1980).

164 BHATTACHARYA, WALKER

cesses may be applicable to nonglacial

meso- and macro-tidal deltaic settings.

Leithold et

a/.

(1989) and Kreisa

et

a/.

(1989) document tidal cyclicity in

ancient

prodelta sediments.

TCd% Indicators.

in

delta front sands

rinclude herr6gbone cross beddifjidal

'

bundles, 4nd reactivation surface3

(Chapter 1

I),

although these features

are also found in many nondeltaic tidal

settings. Some of the "tide-dominated

deltas" that have been identified in the

literature fall equally well into other de-

scriptive settings, for example, offshore

tidal sand ridges (Klang-Langat in

Malaysia) or estuaries (Ord River in

Australia). We therefore emphasize that

the deltaic terminology can only be

applied where three-dimensional control

exists and where the systems clearly

show evidence of seaward progradation.

Figure

12

Major deltaic lobes of the Mississippi Delta; 1

-

Outer Shoal, 2

-

Maringouin, 3

-

Delta plain successions

Teche,

4

-

St. Bernard,

5

-

Lafourche,

6

-

Modern. Lobes 1-3 (plain) belong to transgressive

Distributary channels

systems tracts (TST), and lobes

4-6

(stippled) belong to a highstand systems tract (HST) (see

Facies successions

through

distribu-

Fig. 13). Heavy dots indicate subaqueous sand bodies; in lobe 1, Outer Shoal and in lobe 2,

Ship Shoal. The heavy line, particularly around the margins of lobes

4

and

5,

indicates barrier

taries (Fig'

9,

are erosionally

based'

islands. The line

A-A'

shows the location of Figure 13. Simplified from Boyd

et

al. (1 989).

Filling commonly takes place after

channel switching and lobe abandon-

ment. At this time, the distributary

channel may develop into an estuary,

and the fill is commonly transgressive

(see also Chapter 11).

lT@%id@vsuc+

tesxan wT~.tefid:-F6W1e upwarQt. with

some preserved fluvially derived facies

.:

at the base3 and a greater propqrtion of

3

marine facies in the upper part of the

$

channel fill. The extent of marine facies

development will depend on the degree

of

fluvial dominance. Examples of these

different types were presented by

Bhat-

tacharya and Walker (1991) from dis-

tributaries in Cretaceous deltaic

systems in Alberta (Fig. 9).

The overall proportion of distributary

channel facies is a function of the type

of delta. In general, the more

wave-

dominated the delta, the greater will be

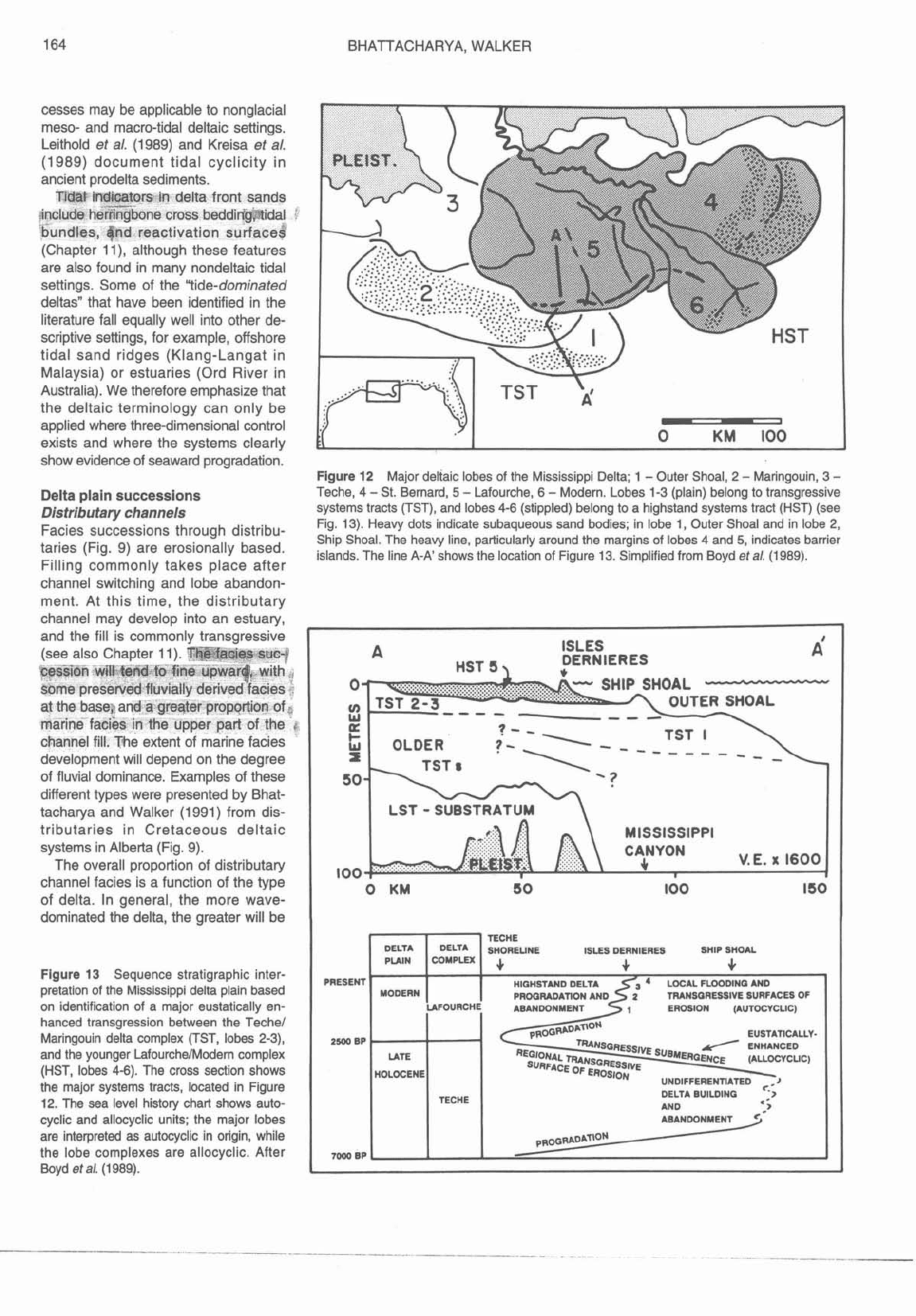

Figure

13

Sequence stratigraphic inter-

pretation of the Mississippi delta plain based

on identification of a major eustatically en-

hanced transgression between the

Techel

Maringouin delta complex (TST, lobes 2-3),

and the younger

LafourchelModem complex

(HST, lobes

4-6). The cross section shows

the major systems tracts, located in Figure

12. The sea level history chart shows

auto-

cyclic and allocyclic units; the major lobes

are interpreted as autocyclic in origin, while

the lobe complexes are allocyclic. After

Boyd

et

al. (1 989).

A

ISLES

DERNlERES

A'

OUTER SHOAL

------

MISSISSIPPI

V. E.

x

1600

1

\

0

KM SO

100

150

TECHE

DELTA DELTA

SHORELINE ISLES

DERNIERES

SHIP SHOAL

PLAIN

COMPLEX

4

+

.I

PRESENT

'

LOCAL

FLOODINa *No

MODERN

TRANSQRESSIVE

SURFACES

OF

EROSION

(AUTOCYCLIC)

EUSTATICALLY-

2500

BP

/

ENHANCED

LATE

HOLOCENE

ECHE

DELTA

BUILDING

*->

AND ABANDONMENV*

>

7000

BP

i

-

-

-

-

-

---

_

.

..~

.-

9. DELTAS

the proportion of lobe sediment with

more limited amounts of interlobe and

distributary channel facies.

lnterdistributary areas

lnterdistributary and interlobe areas

tend to be less sandy, and commonly

contain a series of relatively thin,

stacked coarsening- and fining-upward

facies successions (Fig. 10). These

are usually less than ten metres thick,

and much more irregular than the suc-

cessions found in prograding deltaic

lobes (compare Figs. 8 and 10; also

see Elliott, 1974). The proportion of

lobe versus interlobe successions will

depend on the nature and type of delta

system and will tend to be greater in

more river- or tide-influenced systems

and less in wave-dominated deltas.

lnterdistributary areas

in

river-dominated deltas

An interdistributary bay is filled by over-

bank spilling of fine-grained material

from the river during flood stages.

There is an overall shallowing-upward

facies succession, associated with a

trend from more marine to more

non-

marine facies, but commonly without

the deposition of thick sands (Fig. 10).

REOCCUPATION

*

This represents the transition from off-

shore

prodelta mudstones into delta top

facies without the development of a

sandy shoreline (Walker and Harms,

1971; Bhattacharya and Walker, 1991).

The muddy nature of interdistributary

bay successions may be punctuated by

sandy crevasse splay or channel de-

posits that may produce thin coars-

ening or fining cycles (Coleman and

Prior, 1982; Elliott, 1974). The succes-

sion may grade into rooted coaly

mud-

stones or coals representing a variety

of swamp, marsh and lacustrine envi-

ronments. In addition, beach sands as-

sociated with the development of

barrier strandplains, spits, or cheniers

may be present at the tops of these

successions, although they will prob-

ably be relatively thin.

Interlobe areas

may also act as the locus for

prograda-

tion of the next lobe and may be ero-

sively truncated by younger distributary

channels.

lnterdistributary areas in

wave-influenced deltas

lnterdistributary bays may often be

completely closed off by

barrierlbeach

complexes in wave-dominated deltas

(e.g., the Nile, and the Sao Francisco in

EROSIONAL HEADLAND

I

I

SUBSIDENCE

3

BARRIER ISLAND ARC

Brazil), resulting in extensive back-

barrier lagoons. These may be filled

from the landward side by progradation

of

bayhead deltas or from the barrier

side by storm washovers (as discussed

in Chapter 10). Deposits are commonly

organic-rich, with marsh vegetation or

mangroves.

lnterdistributary areas in

tide-influenced deltas

Tidal processes may be important in

interdistributary bays (even in

river-

dominated deltas) resulting in tidally

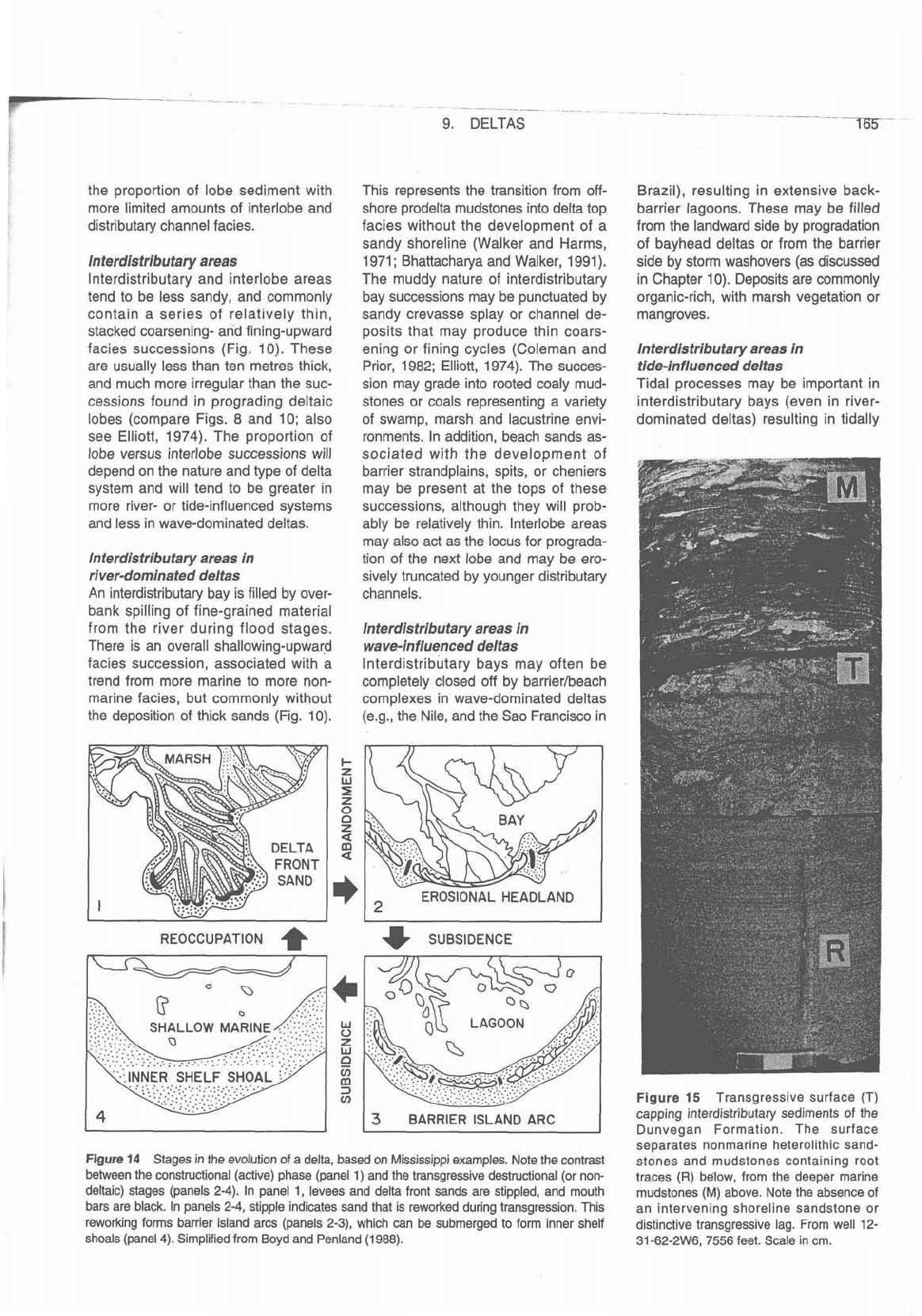

Figure

15

Transgressive surface (T)

capping interdistributary sediments of the

Dunveqan Formation. The surface

separates nonmarine heterolithic sand-

Figure

14

Stages in the evolution of a delta, based on Mississippi examples. Note the contrast

stones and mudstones containing root

between the constructional (active) phase (panel 1) and the transgressive

destructional (or non-

traces

(R)

below, from the deeper marine

deltaic) stages (panels

2-4). In panel 1, levees and delta front sands are stippled, and mouth

mudstones

(M)

above. Note the absence of

bars are black. In panels 2-4, stipple indicates sand that is reworked during transgression. This

an intervening shoreline sandstone or

reworking forms barrier island arcs (panels

2-3),

which can be submerged to form inner shelf

distinctive transgressive lag. From well

12-

shoals (panel

4).

Simplified from Boyd and Penland (1988).

31-62-2W6, 7556 feet. Scale in

cm.

166 BHATTACHARYA, WALKER

influenced facies such as tidal flats or

tidal channels (Allen

et

a/.,

1979;

Ramos and Galloway, 1990). These

are especially common in modern tid-

ally influenced deltas such as the

Niger, Fraser, and Mahakham deltas.

Ancient examples of tidally influenced

facies in delta plain settings include

those published by Ramos and

Galloway (1 990), Eriksson (1 979) and

Rahmani (1988).

CASE STUDIES OF MODERN

DELTAS AND THEIR ANCIENT

COUNTERPARTS

The delta models described above are

based on the morphologies and facies

patterns of several modern deltas. A

few case studies will be discussed, to

place the facies successions into a

larger context.

NORTHWEST

\

River-dominated deltas

The modern Mississippi birdfoot lobe

(Balize delta) is the type example of

an elongate, river-dominated delta

(Fig.

3).

It is characterized by a

skeleton of radiating, shore-normal bar

finger sands that formed by the pro-

gradation of distributary mouth bars

(Fisk, 1961). The very straight nature

of the bar fingers is largely due to lack

of reworking of sands in the marine

environment and the muddy nature of

the sediments; wave action is slight

and the tidal range is very low. The

birdfoot is also situated in relatively

deep water, close to the edge of the

continental shelf, where the subaerial

levees of the distributaries can only

build straight forward on top of the

mouth bar deposits. Overall, the facies

are dominated by muds with

well-de-

veloped coarsening-upward mouth bar

successions (Fig. 7) within the bar

fingers. Associated sands in the imme-

diate subsurface (Coleman, 1981)

show a greater degree of strike align-

ment related to growth faults. The rate

of

fluvial sediment input is so great,

and the marine processes relatively so

weak, that the skeleton of bar finger

sands, radiating from the Head of

Passes, has developed during the last

600-800 years. The skeleton has been

fleshed-out by deposition in

interdis-

tributary bays from historically dated

crevasses in the channel levees (Fig.

5).

Each bay fill is in effect a small

delta, building from the crevasse in the

levee.

The modern Mississippi

birdfoot

delta owes its morphology to an un-

usual set of circumstances (very high

SOUTHEAST

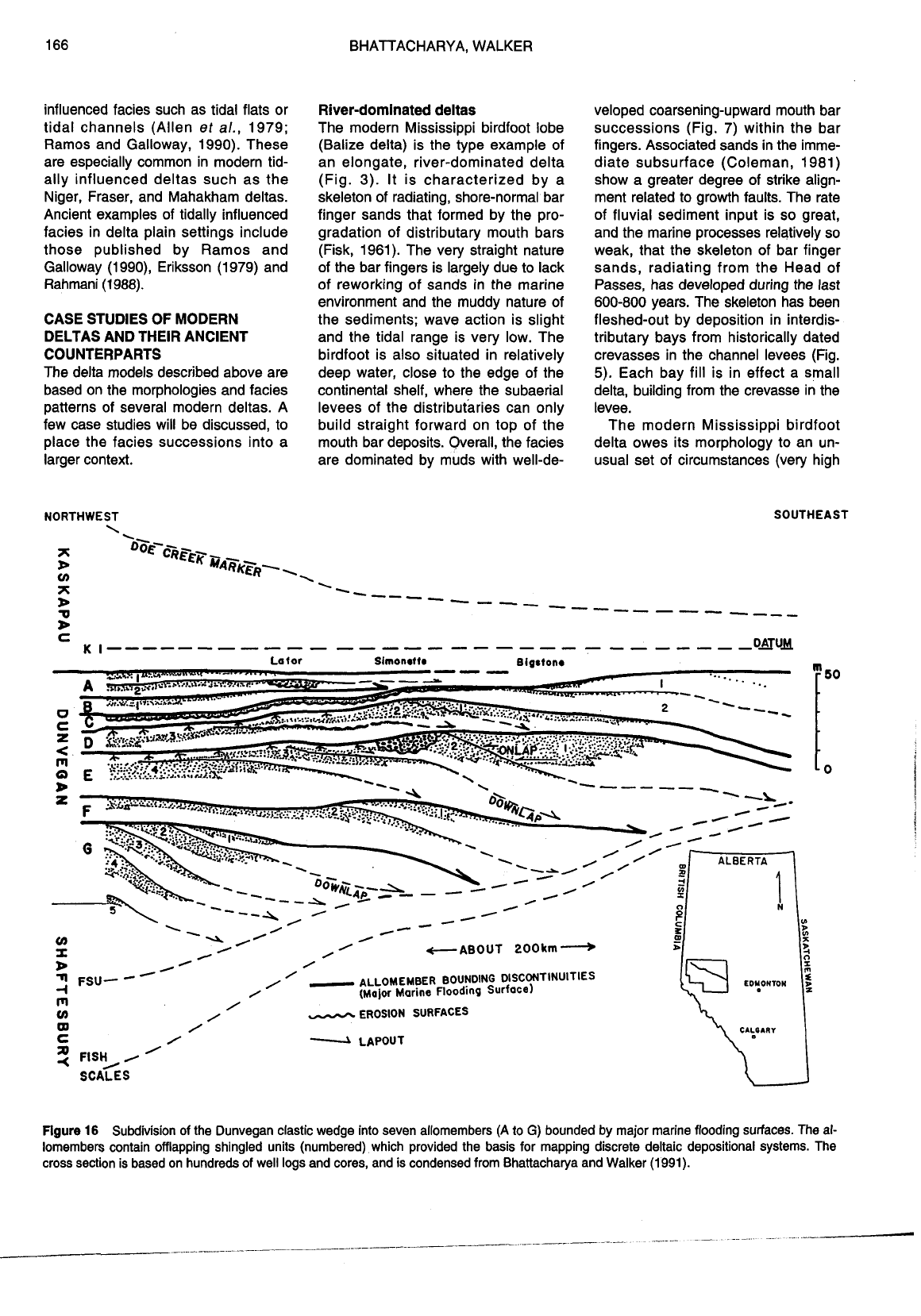

Figure

16

Subdivision of the Dunvegan clastic wedge into seven allomembers

(A

to

G)

bounded by major marine flooding surfaces. The al-

lomembers contain offlapping shingled units (numbered) which provided the basis for mapping discrete deltaic depositional systems. The

cross section is based on hundreds of well logs and cores, and is condensed from Bhattacharya and Walker

(1991).