Video Art A Guided Tour

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

and Adam Chodzko began to use computers to introduce random elements

to abstruse narratives, a chance technique that was already well established

in avant-garde music from John Cage onwards. Douglas has produced highly

theatrical scenes that are shuffled to create endless narrative permutations. In

the UK, Steve Hawley is also randomising image, sound and subtitle for his

forthcoming series of ‘non-stop cinema’ works. No two visitors to the gallery

or movie theatre see the same work. The arbitrary nature of language and its

tenuous hold over meaning constitute the overriding themes of such works.

Their refusal of linearity in the deployment of narrative themes promotes a less

goal-oriented, secure conceptual framework and introduces a more maze-like,

aleatory and non-hierarchical approach to storytelling. Chance in art, as in life,

throws up the real challenges and surprises.

H I G H - G LO S S A N D S OA P S

The influence of dominant forms of cinematic and televisual narrative persists,

even when lyrical, fanciful or chance elements are introduced. The experience

of life as an extended soap opera is reflected both in the choice of narrative

idiom and in the increasing adoption by artists of Hollywood’s high-gloss

production values. Video-makers like Eija-Lisa Ahtila create pseudo-soaps in

which actors perform significant or difficult moments in life, drawn from stories

told to the artist by real people. In The House (2002) a young woman isolates

herself in a woodland cabin and, like Lilian Gish in The Wind or Catherine

Deneuve in Repulsion, she begins to imagine from external sounds that people

and objects are about to burst through the walls. Unaccountably, the girl

transforms herself into a version of Peter Pan’s Wendy and takes flight through

the woods. The escape into fantasy might be interpreted as the last resort in a

world of manipulated desires. For his part, the Canadian artist Mike Hoolboom

describes his work in the 1990s as ‘documentaries of the imaginary’. No longer

attempting to pursue reality in the medium of truth, his tapes are ‘more faithful

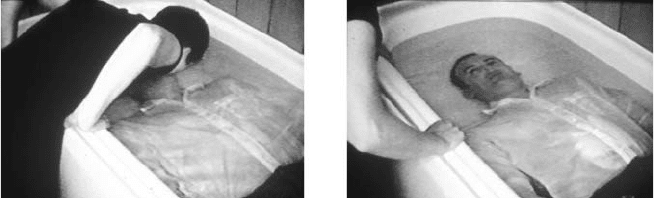

32. Stephanie Smith and Edward Stewart, Mouth to Mouth (1996), videotape.

Courtesy of the artists.

T H E 1 9 9 0 S A N D T H E N E W M I L L E N N I U M • 1 8 7

1 8 8 • V I D E O A R T, A G U I D E D T O U R

renderings of how I dream, or imagine the world to be, or imagine my place

in it’.

38

If the new task of moving image is to transmit the magic of dreams, then

the spectacle of video is now as important as its ability to convey information.

Even Bill Viola is polishing his act. Embracing the new high resolution of digital

video and plasma screens, he links video to an earlier purveyor of dreams, to the

High Renaissance. Appropriating the themes of religious painting, he has been

producing a series of videos that deliberately aspire to the condition of painting

in their hyperrealist crispness. Cinema and fresco painting combine in video

once again to astonish and captivate the jaded eye of the contemporary media

junky. Spectacle is the binding agent, a role once played by the Christian beliefs

evoked by Viola’s work. Gradually, through the 1990s, artists have played down

video’s traditional role as a medium of witness and concentrated on its power

to conjure up an atmosphere, suggest a state of mind and stir the emotions. The

individual subjectivity of the artists, their televisual dreams and hallucinations

are given a Hollywood makeover with the high resolution of plasma screens

and large-scale digital projections. In this respect, video art clearly shares with

mainstream film and video the desire to transport and enchant its audiences. In

this post-mesmeric age, its visual culture saturated with extreme imagery, it is

not an easy task to enthral an audience.

R E A L I T Y V I D E O, R E A L I T Y T V A N D T H E I N T E R N E T

When you are bending down looking at somebody’s anus,

someone else is looking at y

ours

.

Senegalese saying, quoted in Trinh Minh-ha’s Naked Spaces: Living is Round (1985)

The

r

eturn to art history, lost faiths and the imaginary may have been partly

prompted by the colonisation of ‘the personal’ by reality TV. However, many

video artists have continued to use social documentary formats based on

empirical research among individual members of society. We saw how Ann-

Sofi Siden worked with European prostitutes, Kutlug Ataman with transvestites

and ageing divas, and myself with veterans of the Second World War. For her

part, Eija-Lisa Ahtila has focused on teenage girls, Georgina Starr on people

she has never met, while Gillian Wearing took as subjects alcoholic vagrants

and anyone who responded to her advert for individuals willing to confess all

on tape. Those who ‘confessed’ shared the same compulsion that reality show

subjects have to expose themselves to the nation. They know that they must

satisfy broadcasters’ insatiable appetite for the salacious and the grotesque and

so construct identities and one-dimensional ‘life crises’ that will bring them

their fifteen minutes of fame.

39

Viewers revel in the pleasures of schadenfreude

or, as John Stallabrass calls it, ‘holidaying in other people’s misery’. As I argued

in Chapter 7, the subjectivities represented in reality TV are removed from

any social or political context. Although a large degree of self-reflexivity is

maintained, down to the camera operators periodically being drawn into the

fray, what is kept hidden is the programming, funding, commercial and political

pressures that govern the style and content of broadcasting. Television as an

institution is still veiled in secrecy. Many years ago, Rosalind Krauss accused

video artists of retreating into a narcissistic, hermetically sealed world delimited

by the closed-circuit, corralling artist, on-screen image and camera. There is

little doubt that reality TV does much the same work, but this time manages to

separate the mass of individual couch potatoes not only from their own lives

but, in the one-dimensionality of the representations they see on the screen,

from any deeper understanding of contemporary life.

Video art embracing the personal can just as easily share television’s dubious

obsession with ‘freak show’ documentaries and the narcissistic exhibitionism

that is as endemic in art as in televisionland. Tracey Emin unashamedly spills

her guts in her art as she did famously on a BBC Newsnight Review debate

in which she drunkenly staggered off the set whilst giving her co-panellists

the benefit of her colourful views on art in general and the Turner Prize in

particular. Unlike feminists’ careful linking of their experiences to a critique

of a patriarchal political system, Emin deals in individualised acts of excess.

As she happily declared to a television interviewer, ‘I wasn’t confessing, I was

throwing up.’ The 1990s did not invent narcissism. Even 1980s feminists could

indulge in introspective confessionals, much encouraged by the unblinking

stare of the video camera and its ability to record over long periods of time.

One might think that any woman’s experience aired in public is by extension a

political act, especially at times when women have not been able to speak out.

Back in the 1980s, Martha Rosler held the view that the personal is not political

when ‘the attention narrows to the privileged tinkering with, or attention to

one’s solely private sphere, divorced from any collective struggle or publicly

conjoined act and simply names the personal practice as political. For art this

can mean doing work that looks like art has always looked, that challenges little,

but about which one asserts that it is valid because it was done by a woman.’

40

Contemporary reality television and the individualism of art in the early 1990s

contributed to the gushing of purely therapeutic confessionals throughout the

culture and did little to change the conditions under which people lived.

The Internet has now become a major repository for these liturgies of

neurotic interiority. Individuals set up web cameras in their homes, sometimes

one in each room, so that the world can tune in, 24 hours a day, to the banality

of their lives.

41

Chris Darke asks perceptively, ‘what is video voyeurism after

all, but a kind of intimate surveillance?’ Contrary to video’s traditional claim

to offer an encounter with reality, this two-way gaze, this mutual super-vision

T H E 1 9 9 0 S A N D T H E N E W M I L L E N N I U M • 1 8 9

1 9 0 • V I D E O A R T, A G U I D E D T O U R

constitutes a flight from reality. Both viewer and viewed suffer a ‘deflection

of consciousness away from the social towards a twilight zone of interactive

waking dreams’.

42

It is electronic contact with those spectral presences on the

Internet that became the subject of recent work by the Canadian video and

performance artist, Tom Sherman. SUB/EXTROS and HALF/LIVES (2001) are

constructed fr

om downloaded footage of unnamed webcam broadcasters. Men

and women of all ages and physical types sit, apparently transfixed by their

monitors, their faces lit by an unearthly greenish cast emanating from the screen.

Sherman adds to the slow-scanning images his own soundtracks consisting of a

combined monologue and music track composed in collaboration with Bernhard

Loibner. Although intent on long-distance communication, these ‘webcamers’

seem painfully alone, addictively plugged into an interaction, not so much with

another person as with a system of communication that allows the illusion of

contact while avoiding the risks of face-to-face human intercourse.

The French artist Patrick Bernier actualises the desire of webcasters to open

the intimate spaces of their homes to others. In Hébergement/Hostings (2001)

he approaches individuals offering a link to their website from his exhibition

in exchange for lodgings. In this way, Bernier is ‘running through the two-way

mirror’ of the Internet and physically invading their homes. ‘Already a voyeur, I

make myself visible’, he declares.

43

Having reached the inner sanctum, Bernier

33. Tom Sherman, SUB/EXTROS (2001), videotape, 5 min. 30 sec. Music:

Bernhard Loibner. Courtesy of the artist.

the artist-interloper reveals those parts of the house that the restricted, keyhole

range of the webcam cannot reach. Artists in the UK, like the Wades and Fran

Cottell, are also frustrated by the lack of real contact on the Internet and have

opened their homes to the public. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there has

been a spate of ‘relational’ art that involves the public in participatory activities

like eating, telephoning or kicking a football around the gallery. I take this as

further evidence that artists are combating the fear of actual human contact

fuelled by virtual reality, cyber sex and other inventions of the communication

age. Back in 1988, another French artist, Pierrick Sorin, made the definitive

parody of artists’ and webcasters’ compulsive exhibitionism. C’est mignon tout

ça (1988) reveals the artist admiring his own anal caresses by means of a closed-

cir

cuit

video system whilst dressed in women’s black underwear. The widespread

navel- or anal-gazing that the work satirises confirms the dissatisfaction and

lack of completeness that Sherman and Bernier’s Internet subjects also betray.

It would appear that with the help of video cameras, many of us are slipping

into an exclusive relationship with our own nether regions. The question then

arises: how can the twenty-first-century video artist combat both the insidious

narcissism of western culture and the undifferentiated information overload to

which we are all subjected?

I N P RO V I S I O N A L C O N C L U S I O N

Video began life as a counter-cultural force worrying the edges of both fine

art and broadcast television with which it shared a common technology. Over

the past forty years, video has moved steadily from a marginal practice to the

default medium of twenty-first-century gallery art. Here, the convergence of

formats precipitated by the advent of digital technology has brokered a merger

between the parallel practices of artists’ film and video. With television,

fashion, advertising and the pop industry no longer regarded as the enemy,

many artists now draw freely from existing cultural genres without feeling the

need to develop a critical stance either towards their content or the position

they occupy in the marketing structures of a consumer culture. Moving image

artists not only plunder popular cultural sources for their art, but they also apply

their creativity to commercial fields with many acting as a bridge between the

two. With the exponential expansion of the art world in the last decade and

institutions like the Tate Modern in London drawing in unprecedented numbers

of visitors, awareness of artists’ moving image is now widespread. I doubt

that there exists an advertising or television executive who hasn’t heard of Bill

Viola. Video has come a long way from the days when a dozen aficionados of

the medium gathered after hours for a screening of ‘difficult’ work at a smoke-

filled Air Gallery in London.

T H E 1 9 9 0 S A N D T H E N E W M I L L E N N I U M • 1 9 1

1 9 2 • V I D E O A R T, A G U I D E D T O U R

Many of the belief systems and counter-cultural ambitions of the early avant-

garde have dissolved into postmodern webs of signification and individual

expression. Theoretically, within a plural and pseudo-egalitarian visual culture,

no one representation is given more weight than any other, although the actual

visibility of artists ranges from rock-star status to virtual obscurity. A free-

floating intertextuality has held sway for the last decade against a background of

an ever-diminishing, but ubiquitous, monoculture. Promiscuously quoting the

canon of popular culture and high art, contemporary image-makers appropriate

the original while often reducing the act to stylistic gesturing that is only as

good as its novelty value. Within a culture defined by a short attention span

and an insatiable desire for the acquisition of property and consumer goods, art

struggles to defend its traditional right to address the complex and unfathomable

questions of human existence. Seduced by the rewards of venture capitalism

or a simple desire to make a living, video artists have bought into the market

place represented by the commercial gallery system, whilst simultaneously

attempting to create in their work an oasis of calm in what Chris Darke calls

the contemporary ‘image storm’.

The gallery as well as civic spaces have been turned into moving image

installations where an aesthetic of spectacle adapted from Hollywood film has

been grafted onto deconstructive methodologies left over from an earlier age.

Although many of the radical formal and conceptual innovations of early video

art have been absorbed by the mainstream or been lost under the mass amnesia

of a commercialised art world, many of their methodologies have survived and

are reinvented against a changed social, political and technological landscape.

Some artists are disillusioned with what they see as the creative bankruptcy of

popular entertainment. In the case of figures like Bill Viola and Daniel Reeves,

they are adopting a new asceticism, a contemplative stillness that both counters

the ‘contemporary excess of meaning and events’

44

and turns the gallery into

a modern cathedral of art. People now go to galleries as a refuge from the

‘image storm’ and for spiritual nourishment on Sundays when they used to go

to church.

As we turned into the twenty-first century, a revival of socially engaged art,

of a ‘relational’ art with a global reach, looked to shatter the postmodern ennui

of the yBa generation. This new political awareness was only occasionally the

product of cultural tourists entering an exotic land and bringing back curiosities

for the amusement of a superior nation. To my mind, the most interesting

work emerging in our so-called post-colonial world has been the mobilisation

of indigenous creative energies whose vision, though inevitably marked by

western influences, cannot but change the conceptual framework and, indeed,

the form that art will take in the future. In the films and videos of artists

like Shirin Neshat and Zacharias Kunuk, political awareness is not seen as

an alternative to aesthetic considerations, but as intrinsic to the business of

speaking out. Beauty and horror co-exist in the reports they send back of their

experiences in what Germaine Greer has called the ‘unsynthesised manifold’, in

the messy trenches of reality.

Where traditions of video art persist, moving image will always be deployed

as the factual medium, whether as evidence of historic and political events or as

a personal archive. Tom Sherman warns against the use of video as a catalogue

of memory binding together ‘the loose ends of our imperfect memories’.

45

The realism of video has a tendency to make us forget how easily it is edited

and reworked just as our memories are constructed and reconstructed over

time. For those of us in the West, the moving image artist will always be up

against the editing of reality in pre-existing forms of television. Video art will,

of necessity, maintain a dialogue with video games, picture messaging, the

proliferating linguistic practices of the Internet and whatever communication

systems the new century throws up. In this context, artists will constantly

reflect their times, but they can still act as the ‘ghost in the machine’, the

irritant that questions the power structures and entrenched practices of the

image-brokers. In their constant search for innovative imaging techniques,

they will extend the boundaries of what is possible with new technologies and

communication systems. Tom Sherman has proposed that in the information

age, artists could act as ‘intelligent agents’, guides or ciphers steering viewers

through the morass of undigested information that bombards us every day.

Artists are endowed with the skill of repositioning the viewer’s perceptions

and drawing meaning out of the clamour of an increasingly mediatised world.

They will always illuminate the ‘other’ point of view, the blind side, that which

is hidden under the manipulations of vested interests dominating the political,

industrial and imperial West.

By virtue of their medium, moving image artists will always be in the business

of enchantment and wonder. They will systematically pursue beauty even

though, in the past, few have admitted to this quest. The aesthetic dimension

of moving image has been harnessed as a conductor of meaning from the

beginning and its ability to move the emotions will continue to play a part

in whatever project artists undertake. Given my background in oppositional

video, I would like to think that artists would set aside their disillusionment

with party politics and once again contribute to collective endeavours like the

anti-capitalist movement, environmental conservation and the international

condemnation of American expansionism. However directly or indirectly they

address contemporary issues, artists must always ask the difficult, unfashionable

and prescient questions. There is a degree of clairvoyance involved, a leap of

faith and a mobilisation of that old enemy of postmodern cynicism, the unruly

artistic imagination.

T H E 1 9 9 0 S A N D T H E N E W M I L L E N N I U M • 1 9 3

Notes

C H A P T E R 1 : I N T RO D U C T I O N – F RO M T H E M A RG I N S T O T H E

M A I N S T R E A M

1. Throughout this book, I use the term ‘televisual’ in the sense that it was first

employed in the 1970s by Stuart Marshall, namely to denote the language and

representational conventions of realism in broadcast television with the implied

receptivity, if not passivity of the viewer. I distinguish the term from John Thornton

Caldwell’s later use of the noun ‘televisuality’, referring to visually arresting

material on television designed to harness the aesthetic sensibilities of the viewer.

See Caldwell, Televisuality: Style, Crisis, and Authority in American Television,

Rutger

s University Press, 1995.

2. The Sony Portapak was a bulky portable video recorder that was powered by

large, rechargeable batteries and linked to a camera by a power cable. It took video

cassettes that allowed twenty minutes of continuous recording time.

3. Paik is widely accepted as a pioneer in the field although antecedents and parallel

developments have been identified elsewhere. See for example Edith Decker-

Phillips, Paik Video, Barrytown Ltd., 1998.

4. Roland Barthes, Image, Music, Text, Fontana/Collins, 1977.

5. Peter Kardia, ‘Making a Spectacle’, Art Monthly, no. 193, 1996.

6.

It

could be argued that artist-run spaces still exist and that contemporary art on

the Internet successfully sidesteps the gallery system. A full discussion of this issue

is outside the scope of this book, but I will return to other demotic initiatives in

chapter 7.

7. It

is only recently that American performance tapes have found their way into the

prestigious Kramlich collection.

8. See Amelia Jones, ‘Presence in Absentia, Experiencing Performance as

Documentation’, Art Journal, Winter 1997.

9. Postcard (1984), Air Gallery, London.

10.

Douglas Crimp, ‘The Photographic Activity in Postmodernism’, Performance Texts

and Documents, Parachute, 1980.

11.

Bruno Bettleheim, The Uses of Enchantment, Peregrine Books, 1976.

12. Nam June Paik, ‘Input-Time and Output-Time’, in Ira Schneider and Beryl Korot

(eds.), Video Art: An Anthology, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

13. Dan Reeves in conversation with Chris Meigh-Andrews, www.meigh-andrews.

com.

14

. All quotes by Marty St. James taken from ‘Video Telepathies’, Filmwaves, No. 15,

2001.

15. Frank Poper quoting Hervé Fisher in Art of the Electronic Age, Thames and Hudson,

1993.

16. See Dan R

eeves in conversation with Chris Meigh-Andrews, op. cit.

C H A P T E R 2 : T H E M O D E R N I S T I N H E R I TA N C E

1. Stuart Marshall, ‘Institutions/Conjunctures/Practice’, in Recent British Video

catalogue, 1983.

2. For a comprehensive account of the deconstructive techniques of structural film-

making by artists, see A.L. Rees, A History of Experimental Film and Video, BFI

Publishing, 1999.

3. F

or a fuller discussion of Paik’s relationship to John Cage, see Edith Decker-Phillips

in Paik Video, Barrytown Ltd, 1998.

4. Quoted b

y Edith Decker-Phillips, ibid.

5. Pierre Théberge on Michael Snow, in Schneider and Korot (eds.), Video Art: An

Anthology, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

6. Richar

d Serra, in Schneider and Korot (eds.), Video Art: An Anthology.

7. See

Mick Hartney, An Incomplete and Highly Contentious Summary of the Early

Chronology of Video Art (1959–1976), London Video Arts catalogue, 1984.

8. I will consider some exceptions in my discussion of UK scratch video in the 1980s

and its reinvention in contemporary Canadian video. See chapter 6.

9. Edith Decker-Phillips, op. cit.

C H A P T E R 3 : D I S RU P T I N G T H E C O N T E N T

1. David Ross, ‘The Personal Attitude’, in Schneider and Korot (eds.), Video Art: An

Anthology, op. cit.

2. Sally

Potter, ‘On shows’, in the catalogue of About Time, Performance and

Installation by 21 Women Artists, ICA publications, 1980 (unpaginated).

3. Dara Gellman, catalogue entry in UK/Canadian Video Exchange 2000, London,

Toronto.

4. Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses, Women, Art and Ideology,

Routledge & K

egan Paul, 1981.

5. This view held sway for many years partly as a result of Laura Mulvey’s influential

article ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, Vol. 16, 1975, pp. 6–18.

6. Eric Cameron, ‘Structural Video in Canada’, Studio International, 1972.

7. Luc

y Lippard, ‘The Pleasures and Pains of Rebirth – European Women’s Art’, in

Feminist Essays on Women’s Art, Dutton Press, 1976.

N O T E S • 1 9 5

1 9 6 • V I D E O A R T, A G U I D E D T O U R

8. Jayne Parker, The Undercut Reader, Wallflower Press, 2002, p.118.

9. See Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, Routledge, 1993.

10. See Jean Fisher, ‘Reflections on Echo – Sound by women artists in Britain’, in Chrissie

Iles (ed.), Signs of the Times catalogue, Oxford Museum of Modern Art, 1990, pp.

60–7.

11. Vera Frenkel’s own description of the work in a correspondence with the author.

12. Vera Frenkel, from the script for ‘The Last Screening Room’, in Peggy Gale and Lisa

Steele (eds.), Video re/View: The (Best) Source for Critical Writings on Canadian

Artists’ Video, Art Metropole and Vtape, 1996.

13. T

amara Krikorian quoted in Julia Knight (ed.), Diverse Practices: A Critical Reader

on British Video Art

, Luton Press/Arts Council of England, 1996, p. 77.

C H A P T E R 4 : M A S C U L I N I T I E S

1. In 1977, I was accused of a similarly reductive approach to masculinity when Annie

Wright and I spent some time disguised as men. Andre van Niekerk reproached

me for my conception of what it means to be a man with this scathing comment:

‘Man? Perhaps we should substitute that word for dirty, oily and thoroughly

unwholesome, depraved person.’

2. Marilyn Frye quoted by Peggy Phelan in Unmarked: The Politics of Performance,

Routledge

, 1993, p. 101.

3. Peggy Phelan, Unmarked, op. cit.

4. Bruce

W. Ferguson, ‘Colin Campbell: Otherwise Worldly’, in Gale and Steele (eds.),

Video re/View, op. cit.

5. Ibid.

6.

Stuart Marshall quoted by Rebecca Dobbs in David Curtis (ed.), A Directory of

British Film & Video Artists, Arts Council of England publication, 1996.

7. John

Greyson, ‘Double Agents: Video Art addressing AIDS’, in Gale and Steele

(eds.), Video re/View, op. cit.

8. Negativ

e capability was the characteristic first attributed to male poets like Keats

who were seen to have flexible ego boundaries enabling them to take on different

identities and sensibilities. It was also a quality that was attributed to women’s art

in the 1980s.

9. Vito Acconci in conversation with Klaus Biesenbach, Video Acts: Single Channel

Works from the Collections of Pamela and Richard Kramlich and the New Art Trust

catalogue, P

.S.1 New York, ICA London, 2003.

10. Tom Ryan, ‘Roots of Masculinity’, in Andy Metcalf and Martin Humphreys (eds.),

The Sexuality of Men, Pluto Press, 1985.

11.

Ibid.

12. See Linda Nochlin, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, in T.B. Hess

and E. Baker (eds.), Art and Sexual Politics, Collier Macmillan, 1973.

13. R

ozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses: Women, Art & Ideology,

Routledge & K

egan Paul, 1981.

14. See chapter 6 for an account of Bourn’s work.