The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

LAYING THE FOUNDATION 237

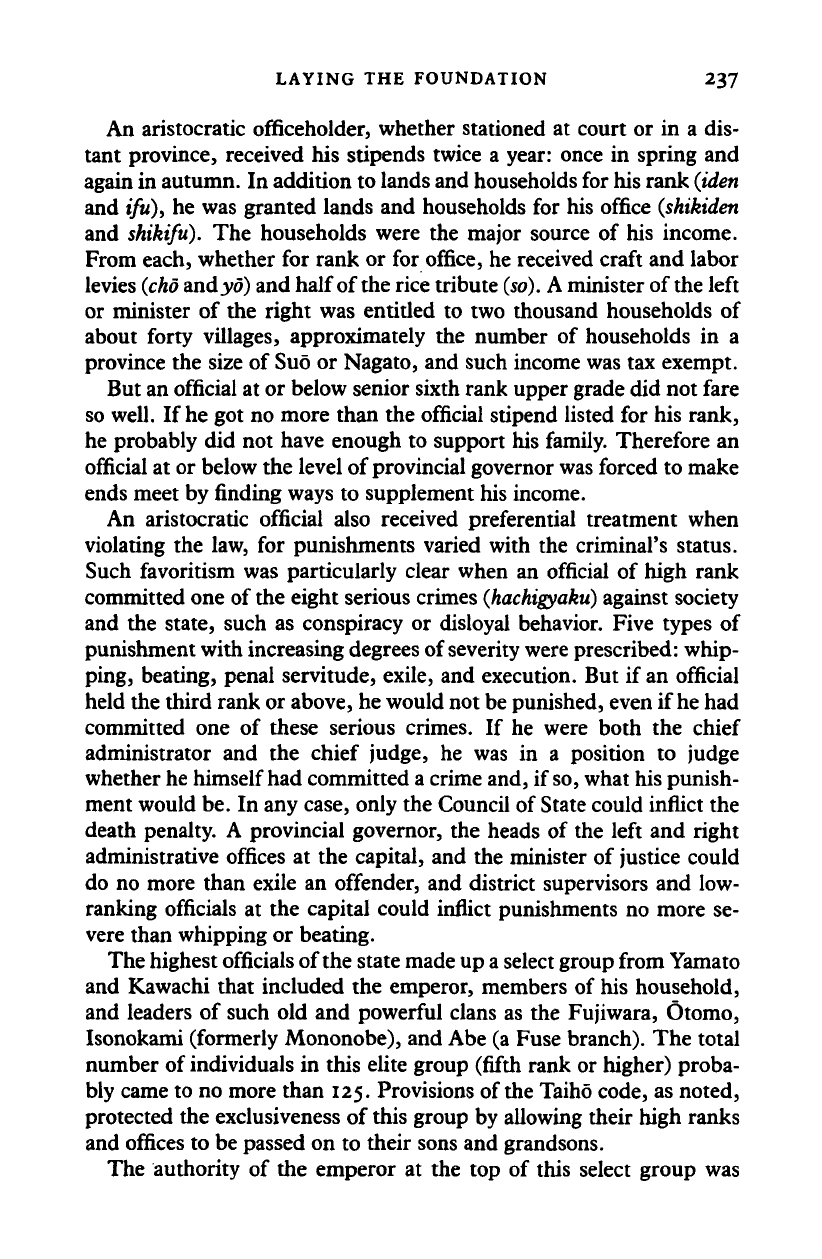

An aristocratic officeholder, whether stationed at court or in a dis-

tant province, received his stipends twice a year: once in spring and

again in autumn. In addition to lands and households for his rank

(iden

and ifu), he was granted lands and households for his office

(shikiden

and shikifu). The households were the major source of his income.

From each, whether for rank or for office, he received craft and labor

levies

(cho

and

.yd)

and half of the rice tribute

(so).

A

minister of

the

left

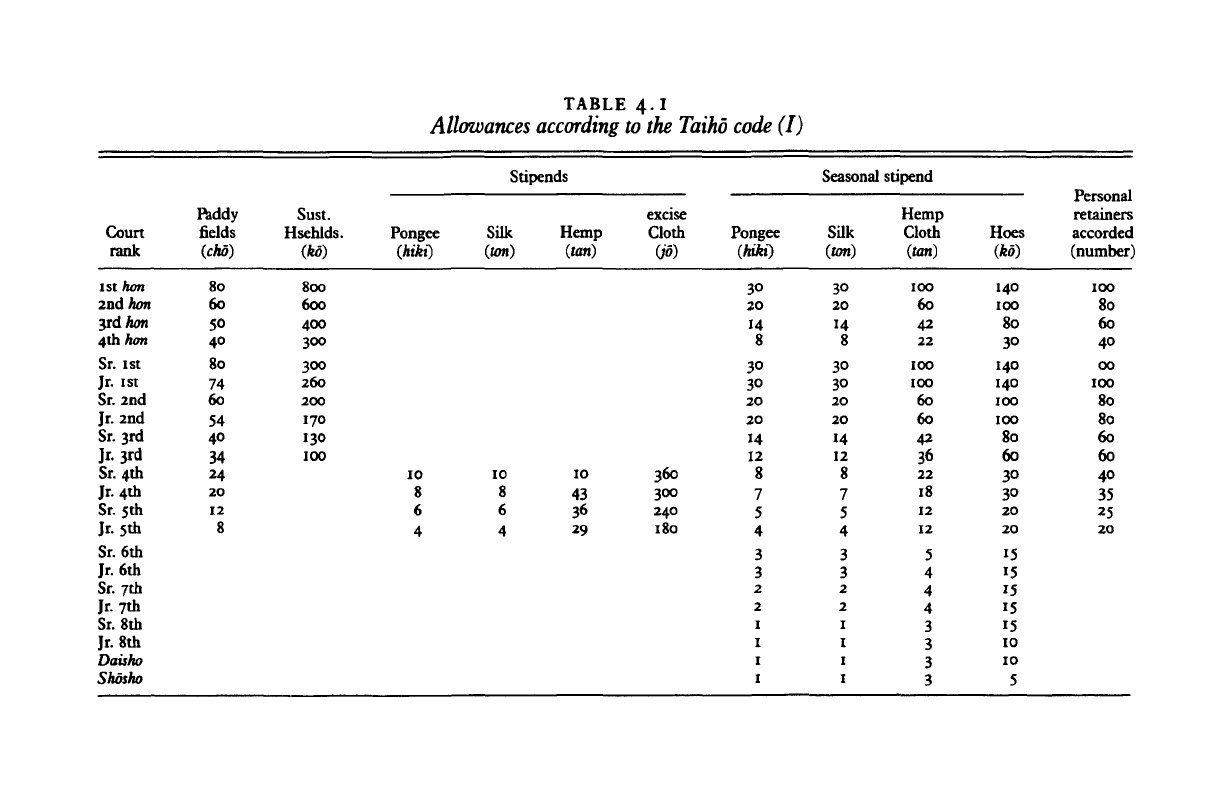

or minister of the right was entitled to two thousand households of

about forty villages, approximately the number of households in a

province the size of Suo or Nagato, and such income was tax exempt.

But an official at or below senior sixth rank upper grade did not fare

so well. If he got no more than the official stipend listed for his rank,

he probably did not have enough to support his family. Therefore an

official at or below the level of provincial governor was forced to make

ends meet by finding ways to supplement his income.

An aristocratic official also received preferential treatment when

violating the law, for punishments varied with the criminal's status.

Such favoritism was particularly clear when an official of high rank

committed one of the eight serious crimes

(hachigyaku)

against society

and the state, such as conspiracy or disloyal behavior. Five types of

punishment with increasing degrees of severity were prescribed: whip-

ping, beating, penal servitude, exile, and execution. But if an official

held the third rank or above, he would not be punished, even if he had

committed one of these serious crimes. If he were both the chief

administrator and the chief judge, he was in a position to judge

whether he himself had committed a crime and, if

so,

what his punish-

ment would be. In any case, only the Council of State could inflict the

death penalty. A provincial governor, the heads of the left and right

administrative offices at the capital, and the minister of justice could

do no more than exile an offender, and district supervisors and low-

ranking officials at the capital could inflict punishments no more se-

vere than whipping or beating.

The highest officials of the state made up

a

select group from Yamato

and Kawachi that included the emperor, members of his household,

and leaders of such old and powerful clans as the Fujiwara, Otomo,

Isonokami (formerly Mononobe), and Abe (a Fuse branch). The total

number of individuals in this elite group (fifth rank or higher) proba-

bly came to no more than 125. Provisions of the Taiho code, as noted,

protected the exclusiveness of this group by allowing their high ranks

and offices to be passed on to their sons and grandsons.

The authority of the emperor at the top of this select group was

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

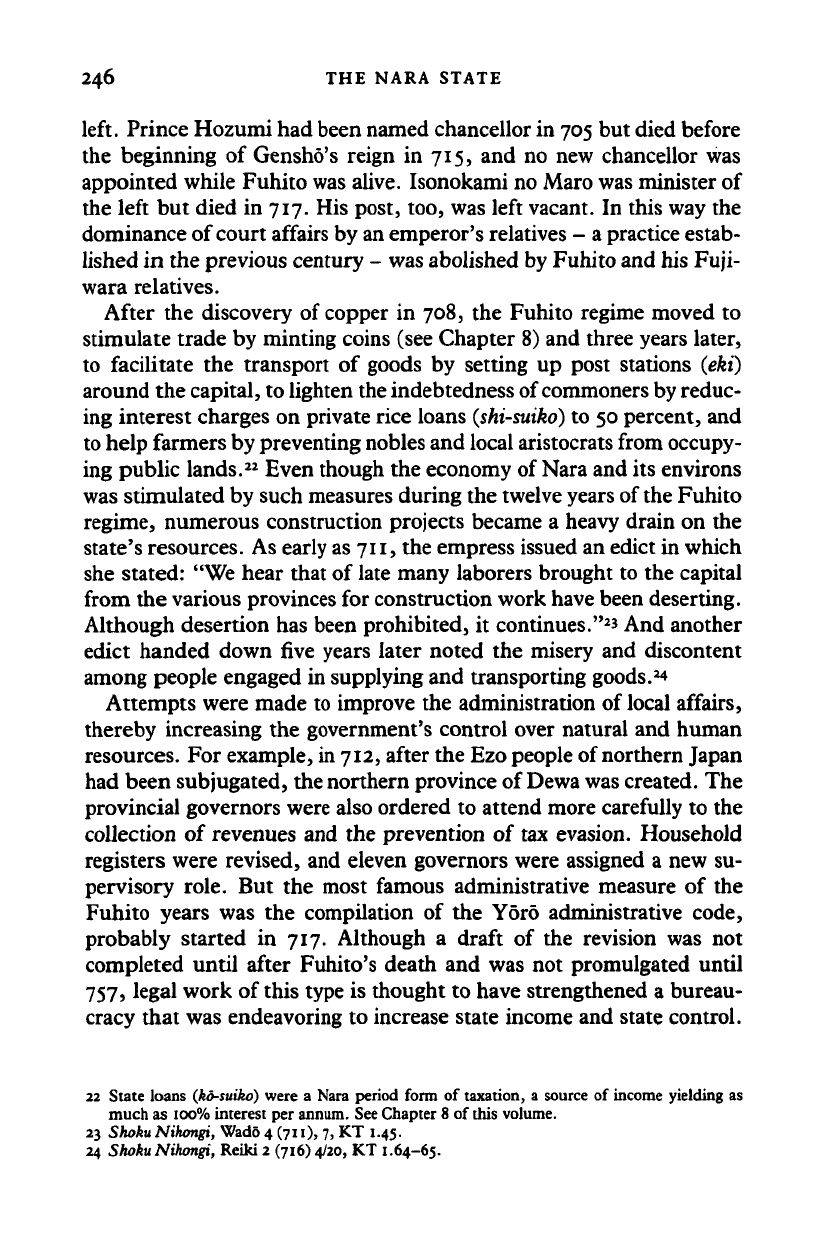

TABLE

4.I

Allowances according

to the

Taiho code

(I)

Court

rank

ist

hon

2nd

hon

3rd hon

4th

hon

Sr.

ist

Jr.

ist

Sr.

2nd

Jr.

2nd

Sr.

3rd

Jr.

3rd

Sr.

4th

Jr.

4th

Sr.

5th

Jr.

5th

Sr.

6th

Jr.

6th

Sr.

7th

Jr.

7th

Sr.

8th

Jr.

8th

Daisho

Shosho

Faddy

fields

(««)

80

60

50

40

80

74

60

54

40

34

24

20

12

8

Sust.

Hsehlds.

(M)

800

600

400

300

300

260

200

170

130

100

Pongee

(hiki)

10

8

6

4

Stipends

Silk

(urn)

10

8

6

4

Hemp

(tan)

10

43

36

29

excise

Cloth

(jo)

360

300

240

180

Pongee

(hiki)

3°

20

14

8

30

3°

20

20

14

12

8

7

5

4

3

3

2

2

1

1

1

1

Seasonal

Silk

(ton)

3°

20

14

8

30

3°

20

20

14

12

8

7

5

4

3

3

2

2

1

I

1

1

stipend

Hemp

Cloth

(ton)

100

60

42

22

100

100

60

60

42

36

22

18

12

12

5

4

4

4

3

3

3

3

Hoes

(ko)

140

100

80

30

140

140

100

100

80

60

30

30

20

20

15

15

15

15

15

10

10

5

Personal

retainers

accorded

(number)

100

80

60

40

00

100

80

80

60

60

40

35

25

20

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Allowances according

to the

Taihd code

(II)

Personal

Paddy fields Sustenance retainers

Government post (ch6) households (kd) (number)

Minister of state 40 3,000 300

Ministers of left and right 30 2,000 200

Counselors

(dainagon)

20 800 100

Middle counselors

{chunagon)

200 30

Advisers

(sangi)

80

Note: Chmagon by the regulation of

705;

sangi

by that of 730.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

24O THE NARA STATE

great but not unlimited. He could issue an edict ordering the appoint-

ment of a crown prince or minister, but his edict had to be counter-

signed by the chancellor, minister of the left, or minister of the right.

On the other hand, the following matters could not be acted on by the

Council of State until its recommendations had been reported to the

emperor and approved by him: (i) scheduling important state ceremo-

nies like the Great Feast of the Enthronement (Daijosai), (2) increas-

ing or decreasing the government's operating costs, (3) altering the

number of officials, (4) inflicting punishments by death or exile, and

(5) forming or abolishing districts. The emperor could approve or

disapprove a recommendation but could not make amendments. Usu-

ally he approved. In principle, then, the emperor had dictatorial

power, but in practice, his power was limited by the consultative

authority of the Council of State."

How did relationships between the emperor and the Council of State

differ from those of

a

T'ang emperor served by three state organs: the

Secretariat (Chung-shu sheng), the Chancellery (Men-hsia sheng), and

the Department of State Affairs (Shang-shu sheng)? The heads of these

Chinese bodies were the state's highest administrators, but they were

no more than instruments of inquiry and did not have complete author-

ity over their own departments. The Secretariat's highest officer would

draft imperial edicts after receiving instructions from the emperor, and

officials of the Chancellery would examine the draft and make revi-

sions.

Other departmental heads could see memorials and report their

views to the throne. The Secretariat, which administered the six

boards, would see that an edict was implemented after it had been

examined and revised by the Chancellery. But the Chancellery did little

more than look for textual deficiencies and usually did not consider the

edict's contents. China's highest state officials, therefore, did not have

nearly as much authority as did their counterparts in Japan.

Heads of Chinese aristocratic clans were also relatively weak, as we

can see when comparing the ranks given to the sons and grandsons of

high-ranking officeholders with those received by their Japanese coun-

terparts. Chinese law stated that the heirs of first-rank officers were

entitled to senior seventh rank lower grade, whereas in Japan they

would receive fifth rank lower grade. A study of the ranks bestowed

on the sons of officials at lower levels of the aristocracy also shows that

the Japanese were treated better.

19 Seki Akira, "Ritsuryo kizoku ron," Kodai, vol. 3 of Asao Naohiro, Ishii Susumu, Inoue

Mitsusada, Oishi Kaichiro et al., eds., Iwanami koza: Nihon

rekishi

(Tokyo: Iwanami shot

en,

1976),

PP- 38-63.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

NARA AND TODAI-JI 24I

But what made the Japanese bureaucratic structure quite different

from that of China was the Council of Kami Affairs, which was placed

under the emperor at a position equal to that of the Council of State.

The compilers of the Taiho code, though giving close attention to

Chinese law, were obviously intent on preserving and using traditional

sources of sacral authority. Because the Japanese law provided crucial

support for the emperor's spiritual and secular authority, historians

commonly think of these years as the high point of

the

"administrative

and penal law

(ritsuryo)"

order.

NARA AND TODAI-JI

The death of Emperor Mommu (Temmu's grandson) in 707 at the

age of twenty-five came at the beginning of the Nara period's second

phase, when a grand Chinese-style capital and a statewide system of

Buddhist temples (centered at the Todai-ji) were built. Mommu's

death was followed by an upheaval at court from which emerged

two powerful and influential leaders: Fujiwara no Fuhito (659-720)

and Emperor Shomu (701-56). Both became deeply involved in

activities that helped to make this a time of remarkable cultural

achievement.

The upheaval of the

court

Whenever an emperor or empress became ill, it was customary for

prominent shrines and temples to offer up prayers for a speedy recov-

ery. The

Shoku Nihongi's

lack of such references during the

five

months

that preceded Mommu's death thus suggests that he may have been

murdered. The chronicle supplies considerable information about a

succession issue that divided the court and that probably was linked

with Mommu's untimely death. The major question was whether the

next emperor should be Prince Obito (the future Emperor Shomu,

whose mother was Fuhito's daughter) or a Mommu son with a non-

Fujiwara mother (see Figure 4.3). Because Mommu had no brothers,

three living sons of Temmu were also eligible candidates for enthrone-

ment. But none of these princes was selected. Instead, Mommu's

mother ascended the throne as Empress Gemmei. This was considered

to be a partial victory for those who favored Obito's candidacy, as

Gemmei stated that she wanted Obito to succeed her. The enthrone-

ment of Gemmei therefore led Fujiwara no Fuhito to feel that he would

soon have the power and prestige customarily held by

a

maternal grand-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

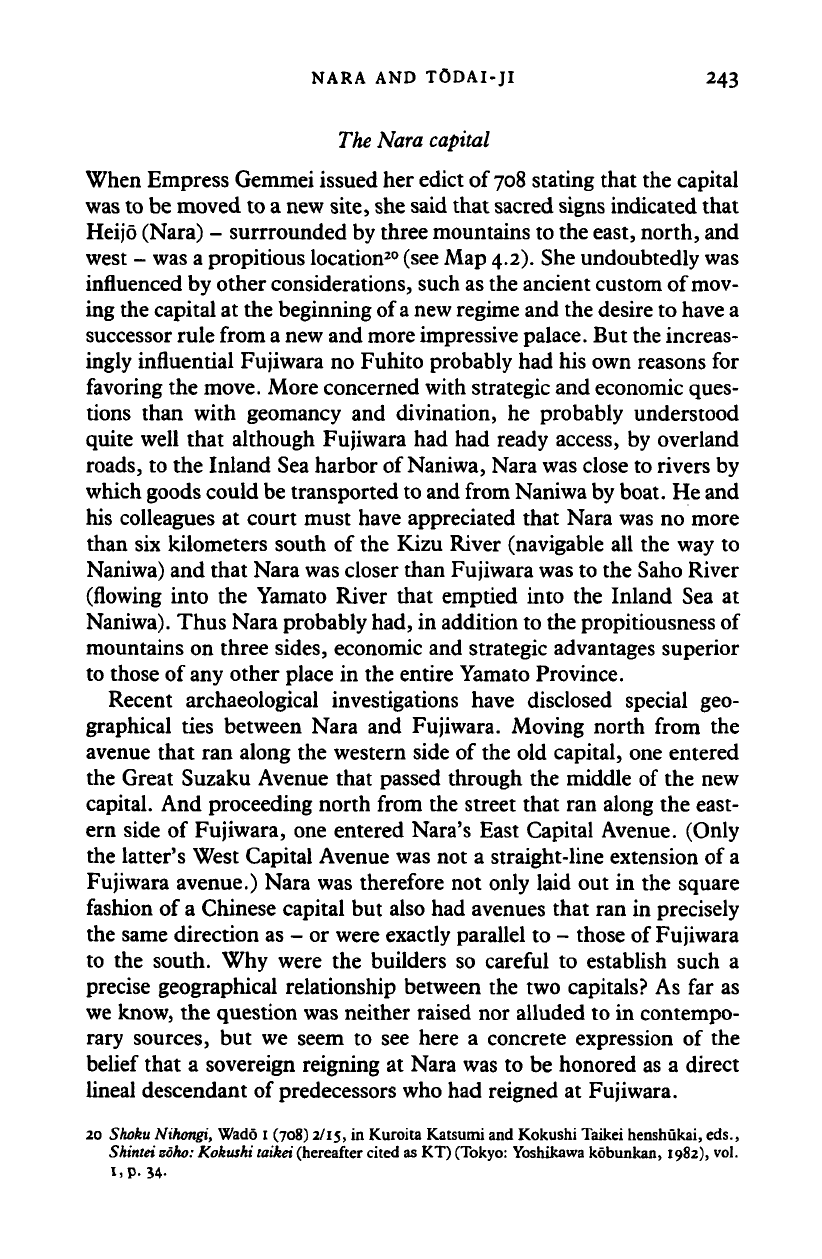

242 THE NARA STATE

Empress Empress Emperor

Gemmei (43) Jito (41)

I

I

L.

Prince

Kusakabe

I

Temmu (40)

Lady

Fujiwara no

Miyako

I

I

• Emperor Empress

Mommu (42) Gensho (44)

Emperor

Shomu (45)

Figure

4.3.

Mommu's successors. Dashed line indicates spousal rela-

tionship; solid line, offspring. (Reign numbers are in parentheses, as

recorded in the

Gunkasho

chronology; see Brown and Ishida, trans.,

The Future

and

the

Past,

pp. 264-78.)

father of

a

reigning emperor, and he moved closer to that coveted goal

in

714

when Prince Obito

was

appointed crown

prince.

But Fuhito died

four years before the prince was enthroned as Emperor Shomu in 724.

The details of Fuhito's rise to power are not known, but as the son

of Fujiwara no Kamatari (614-669), one of the three principal archi-

tects of the 645 rebellion and the subsequent Great Reforms (see

Chapter 3), he was obviously born on a very high rung of the aristo-

cratic ladder. Although not yet forty at the time of Mommu's death in

707 and only at junior second rank, Fuhito is thought to have been the

most influential man at court, strong enough to affect the course of

events leading to the enthronement of a woman who wished to be

succeeded by his grandson.

Two events of historical importance occurred in the year after

Mommu's death: the discovery of copper in the province of Musashi

and an edict by Empress Gemmei announcing that the capital was

being moved to Heijo (hereafter referred to as Nara), which was north

of Fujiwara on the northern rim of the Nara plain. The first event was

considered sufficiently important for the court to decide that 708 was

to be the first year of the Wado (Japan copper) era and for historians to

link the discovery of copper with the rise of a more highly developed

exchange economy and a sudden increase in the number of bronze

statues.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

NARA AND TODAI-JI 243

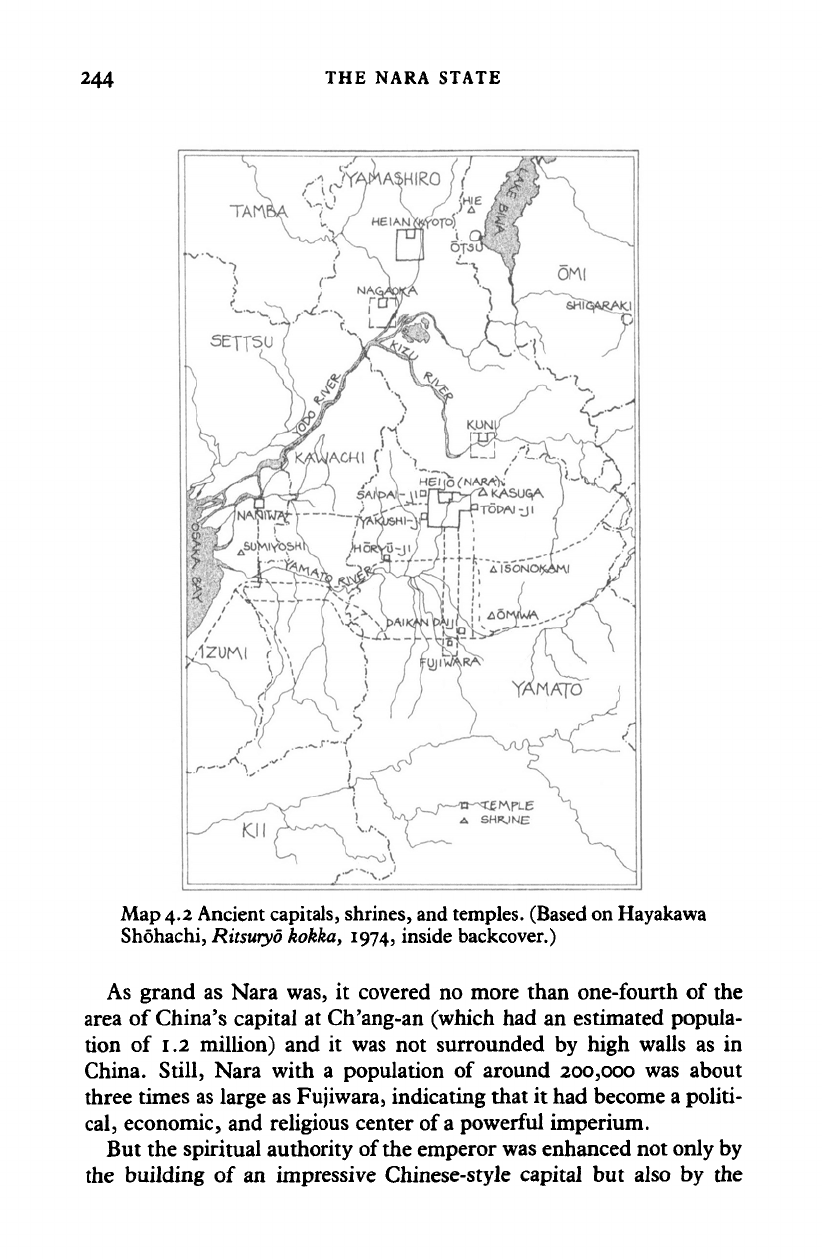

The Nara capital

When Empress Gemmei issued her edict of

708

stating that the capital

was to be moved to a new site, she said that sacred signs indicated that

Heijo (Nara) - surrrounded by three mountains to the east, north, and

west - was a propitious location

20

(see

Map

4.2).

She undoubtedly was

influenced by other considerations, such as the ancient custom of mov-

ing the capital at the beginning of

a

new regime and the desire to have a

successor rule from

a

new and more impressive

palace.

But the increas-

ingly influential Fujiwara no Fuhito probably had his own reasons for

favoring the move. More concerned with strategic and economic ques-

tions than with geomancy and divination, he probably understood

quite well that although Fujiwara had had ready access, by overland

roads,

to the Inland Sea harbor of

Naniwa,

Nara was close to rivers by

which goods could be transported to and from Naniwa by boat. He and

his colleagues at court must have appreciated that Nara was no more

than six kilometers south of the Kizu River (navigable all the way to

Naniwa) and that Nara was closer than Fujiwara was to the Saho River

(flowing into the Yamato River that emptied into the Inland Sea at

Naniwa). Thus Nara probably had, in addition to the propitiousness of

mountains on three sides, economic and strategic advantages superior

to those of any other place in the entire Yamato Province.

Recent archaeological investigations have disclosed special geo-

graphical ties between Nara and Fujiwara. Moving north from the

avenue that ran along the western side of the old capital, one entered

the Great Suzaku Avenue that passed through the middle of the new

capital. And proceeding north from the street that ran along the east-

ern side of Fujiwara, one entered Nara's East Capital Avenue. (Only

the latter's West Capital Avenue was not a straight-line extension of

a

Fujiwara avenue.) Nara was therefore not only laid out in the square

fashion of a Chinese capital but also had avenues that ran in precisely

the same direction as - or were exactly parallel to - those of Fujiwara

to the south. Why were the builders so careful to establish such a

precise geographical relationship between the two capitals? As far as

we know, the question was neither raised nor alluded to in contempo-

rary sources, but we seem to see here a concrete expression of the

belief that a sovereign reigning at Nara was to be honored as a direct

lineal descendant of predecessors who had reigned at Fujiwara.

20 Shoku Nihongi, Wado 1 (708) 2/15, in Kuroita Katsumi and Kokushi Taikei henshukai, eds.,

Shinlei

zoho:

Kokushi taikei (hereafter cited as KT) (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1982), vol.

1,

p. 34.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

244

THE NARA STATE

Map 4.2 Ancient capitals, shrines, and temples. (Based on Hayakawa

Shohachi,

Ritsuryo

kokka,

1974, inside backcover.)

As grand as Nara was, it covered no more than one-fourth of the

area of China's capital at Ch'ang-an (which had an estimated popula-

tion of 1.2 million) and it was not surrounded by high walls as in

China. Still, Nara with a population of around 200,000 was about

three times as large as Fujiwara, indicating that it had become a politi-

cal,

economic, and religious center of a powerful imperium.

But the spiritual authority of the emperor was enhanced not only by

the building of an impressive Chinese-style capital but also by the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

NARA AND TODAI-JI 245

erection of beautiful, massive Buddhist temples. Soon after Empress

Gemmei moved her palace to Nara, temples originally built in Fuji-

wara or elsewhere in the Asuka area (especially the Asuka-dera,

Yakushi-ji, Daian-ji, and Kofuku-ji) were rebuilt at the new capital.

Moreover, additional temples were constructed in provinces all over

the country for an emerging Buddhist system.

The Fuhito

regime

(708 to 720)

Even though Fuhito was the most powerful official at the time of

Emperor Mommu's unexplained death in 707, seven years passed

before his grandson Obito was named crown prince, and ten more

years before Obito was enthroned as Emperor Shomu. Fuhito was

unable to realize his ambitions for Obito sooner because influential

aristocrats favored the enthronement of an imperial son with an impe-

rial mother: either Prince Hironari or Prince Hiroyo, who were sons of

Ishikawa no Toji. Only when Fuhito and his supporters succeeded in

having Ishikawa no Toji expelled from the court in 713 were they able

to arrange the appointment of Obito as crown prince. But even that

did not end the struggle, for Obito was not enthroned after Empress

Gemmei decided to abdicate in 715. The empress elected (or was

forced) to pass the throne to her own daughter, who reigned as Em-

press Gensho (680-748).

Why did Obito - the future Emperor Shomu - fail to reach the

throne in 715? One view is that he was then too young (only fifteen) to

assume the responsibilities of an emperor. But Obito's father Mommu

was placed on the throne at about that same age. A more convincing

theory is that Obito's candidacy met with disfavor because his mother

was a Fujiwara and thus not a member of

the

imperial clan. For nearly

a century the fathers and mothers of all occupants of the throne had

been members of the imperial clan, and this old tradition could not be

easily broken, even by Fuhito

21

(see Figure 4.3).

Although Fuhito did not live to see his grandson's enthronement,

his influence at court was nonetheless considerable. He was appointed

minister of the right in 715 at the beginning of Gensho's reign and

continued to hold that high office until his death in 720. Only two

other officials outranked him: the chancellor and the minister of the

21 The mother of Prince Otomo was not a member of the imperial clan, which may be why the

Nihon shoki does not admit that Otomo ever occupied the throne. If he did become emperor,

an exception was made to the long tradition that both the mother and father of an emperor

should be members of the imperial clan.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

246 THE NARA STATE

left. Prince Hozumi had been named chancellor in 705 but died before

the beginning of Gensho's reign in 715, and no new chancellor was

appointed while Fuhito was alive. Isonokami no Maro was minister of

the left but died in 717. His post, too, was left vacant. In this way the

dominance of court affairs by an emperor's relatives - a practice estab-

lished in the previous century - was abolished by Fuhito and his Fuji-

wara relatives.

After the discovery of copper in 708, the Fuhito regime moved to

stimulate trade by minting coins (see Chapter 8) and three years later,

to facilitate the transport of goods by setting up post stations (eki)

around the capital, to lighten the indebtedness of commoners by reduc-

ing interest charges on private rice loans

(shi-suiko)

to 50 percent, and

to help farmers by preventing nobles and local aristocrats from occupy-

ing public lands.

22

Even though the economy of Nara and its environs

was stimulated by such measures during the twelve years of the Fuhito

regime, numerous construction projects became a heavy drain on the

state's resources. As early as

711,

the empress issued an edict in which

she stated: "We hear that of late many laborers brought to the capital

from the various provinces for construction work have been deserting.

Although desertion has been prohibited, it continues."

2

* And another

edict handed down five years later noted the misery and discontent

among people engaged in supplying and transporting goods.

2

*

Attempts were made to improve the administration of local affairs,

thereby increasing the government's control over natural and human

resources. For example, in 712, after the Ezo people of northern Japan

had been subjugated, the northern province of Dewa was created. The

provincial governors were also ordered to attend more carefully to the

collection of revenues and the prevention of tax evasion. Household

registers were revised, and eleven governors were assigned a new su-

pervisory role. But the most famous administrative measure of the

Fuhito years was the compilation of the Yoro administrative code,

probably started in 717. Although a draft of the revision was not

completed until after Fuhito's death and was not promulgated until

757,

legal work of this type is thought to have strengthened a bureau-

cracy that was endeavoring to increase state income and state control.

22 State loans (ko-suiko) were a Nara period form of taxation, a source of income yielding as

much as 100% interest per annum. See Chapter 8 of this volume.

23 Shoku Nihongi, Wado 4 (711), 7, KT 1.45.

24 Shoku Nihongi, Reiki 2 (716) 4/20, KT

1.64-65.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008