The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

I 9 I I : THE INVISIBLE BOURGEOIS REVOLUTION 743

adherence had really influenced the course of events in 1911. Whether for

or against the revolution, the bourgeoisie remained but a secondary force.

The failure of the 1913 uprising, which brought in its train heavy

taxes and pillaged shops, forced the bourgeoisie to defend its short-term

interests. Yuan Shih-k'ai encouraged the merchants' return to their

traditional social isolation and political abstention. Once victorious, Yuan

did not in fact content himself with eliminating the revolutionary op-

position by forcing its leaders into exile and ordering the dissolution

first of the Kuomintang (November 1913) and then of the parliament

(December 1913). He also directed his attacks against all the representative

systems that had been set up for the benefit of the local elites before and

after the revolution. On 4 February 1914 he suppressed the provincial

and local assemblies which had just been resuscitated during the winter

of 1912-13 on the basis of a much enlarged electorate (25 per cent of the

adult male population).

62

Since the revolution, these local assemblies had

taken over many of the administrative, fiscal and military functions nor-

mally reserved for the state bureaucracy.

6

' In addition, they served as for-

ums and staging-posts for the new associations of industrialists, educators,

artisans and women, which were growing ever more numerous at that

time.

Through these associations a whole stratum of society - the gentry,

but also men of letters and small merchants - found itself integrated into

the political life of the nation. These assemblies represented something

which within the Chinese political tradition came very close to liberalism:

the defence of local interests and social groups shut out or neglected by

the mandarinate. In the eyes of Yuan they thus represented a threat both

to his personal power and to the maintenance of national unity, which he

equated with a rigorous administrative centralization.

For the merchants of Shanghai this was the end of an exceptional

experience. In the municipality of the Chinese city, which had been

re-baptized after the revolution

{shih-cheng

t'ing), the urban gentry of the

shen-shang

had been able to give proof of its capacity for management, its

aptitude for modernization, its comprehension of democratic procedures,

and its interest in major national problems.

6

" The Shanghai business

circles would never again recover this local administrative and political

autonomy. The bureaus of public works, police, and taxes

(kung-hsiin-

62 Cf. Ernest P. Young, 'Politics in the aftermath of revolution: the era of Yuan Shih-k'ai

1919-16', ch. 4 above.

63 On the reduction of the powers of the bureaucracy for the benefit of the local elites, and

on the alliance of these elites with private businessmen between 1911 and

I9i3,cf.

Esherick,

Reform and

revolution

in

China,

246—255.

64 M. Elvin, 'The gentry democracy in Shanghai 1905-1914', 73; 'Shang-hai shih-chih chin-

hua shih-lueh' (Brief history of progress of the Shanghai municipal system) in Shang-hai

t'ung she, ed.

Shang-haiyen-chiu

tzu-liao (Research materials on Shanghai), 75-8.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

744

THE

CHINESE BOURGEOISIE

chiian

chu) which Yuan

had

substituted

for the

former municipality

re-

mained strictly subordinated

to

the local officials. The law

of

1914, which

strengthened government control over

the

chambers

of

commerce,

suc-

ceeded

in

depriving

the

merchants

of

their means

of

political expression.

Thus deprived

of

initiative,

the

merchants seemed

to

lose interest

in

the great ideals which

had

inspired them

for a

dozen years. Unable

to

achieve

a

countrywide acceptance of the modernity which they themselves

had pioneered

in

China, they became absorbed

in the

defence

of

their

short-term interests. Faced with

a

military

and

bureaucratic regime,

which they had

not

sought but had found

no

great difficulty

in

accepting,

they strove

to

strengthen

the

autonomy

of

their geographic

and

social

base,

in

the shadow

of

the foreign presence. Thus we see them requesting

the British consul

at

Nanking

to

extend

the

concession

to the

harbour

and commercial quarter

of

Hsia-kuan, which would thus

be

better pro-

tected.

At

Shanghai some

of

the notables

of

Chapei,

in the

Chinese city,

asked

for the

intervention

of the

International Settlement police

and

sought,

to

quote the ironic words

of

a foreign resident, 'the protection

of

our municipal Tyranny'.

However, Yuan Shih-k'ai's accession

to

power

did not

represent

a

simple restoration

of

the former regime. His presidency was characterized

by

a

new determination

to

further economic development

by

completing

commercial legislation, stabilizing

the

fiscal

and

monetary system,

and

encouraging private enterprise.

6

' Chang Chien,

who was

minister

of

agriculture

and

trade from October 1913

to

December 1915,

had

laws

passed

on

the registration

of

commercial enterprises and corporations, and

on corporation establishment;

he set up

model stations

for

growing

cot-

ton and sugar-cane; and he planned

to

standardize

the

system

of

weights

and measures. Then again

in

February 1914,

at the

instigation

of

Liang

Shih-i,

the

Yuan Shih-k'ai dollar was established, as the first step towards

monetary unification. This willingness

to

encourage business contrasted

oddly with

the

refusal

to

grant

the

smallest scrap

of

power

to the

bour-

geoisie. Here Yuan returned

to the

tradition

of a

modernizing bureauc-

racy,

of

which

he had

been

one of the

principal representatives during

the last years of the Ch'ing. As dictator whose power rested upon the army

and

the

mandarinate Yuan Shih-k'ai

had no

need

to

woo

the

merchants.

It would

be

wrong, therefore,

to see in his

economic policy

any

pledge

to support

the

bourgeoisie.

It

would also

be

wrong

to

attribute

to it the

prosperity enjoyed

by the

great treaty ports during

the

years

of

Yuan's

65

On the

economic policy

of

Yuan Shih-k'ai

cf.

Kikuchi Takaharu,

Chugoku minzoku undo

no kihon kozo

-

taigai boikotto no kenkyu

(Basic structure

of

the Chinese national movement:

a study

of

anti-foreign boycotts), 154-78.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE GOLDEN AGE OF CHINESE CAPITALISM 745

regime. The decisive impulse which was to propel the Chinese bour-

geoisie into its golden age came from elsewhere: from the transformation

of the international situation brought about by the First World War.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF CHINESE CAPITALISM, I 9 I 7-2 3

The limited participation of the bourgeoisie in the revolutionary move-

ment and its conservative reactions when faced with social disorder are

not, however, sufficient to dismiss the concept of bourgeois revolution.

Further study of the consequences of the Revolution of

1911

is called for.

Though of little use for the clarification of the events of 1911-13, perhaps

the concept of bourgeois revolution can usefully be reintroduced in a

longer-term socio-economic analysis. The idea of a transition (between

'feudal methods of production' and 'capitalist methods of production',

between a bureaucratic society and a class society) would then replace the

idea of a revolutionary rupture. Such mutations spring from a long-

term secular process. In China this process began in the sixteenth to eight-

eenth centuries with the appearance of the so-called buds of capitalism

within the traditional economy. This evolution then became very plain

in the nineteenth century, as already noted. After 1911 it continued as

part of the economic modernization and social change of the twentieth

century. Hence it is impossible to encapsulate a development such as the

rise of the bourgeoisie within a single revolutionary occurrence.

But can one not ask whether in the middle term of 10 to 15 years the

Revolution of 1911 did not precipitate industrialization, alter the balance

of power in the bosom of society, and promote the rise of a true bour-

geoisie

?

Certain historians of the French Revolution, when referring to

'this savage capitalism' the forces of which the revolution was considered

to have unleashed, have stressed how slowly it got under way.

66

In China,

by contrast, 10 years after the revolution, at the beginning of the 1920s,

national capitalism was in full swing and a new generation of business-

men had appeared, who were directly linked to industrial production and

the exploitation of a salaried work-force. But this upswing in the urban

economy and society resulted less from a revolution which had long

since been taken over by the militarists than from an economic miracle

caused by the First World War. In semi-colonial China, the logic of the

bourgeois revolution was governed, from outside, by the evolution of

international relations.

66 Francois Furet,

Penser

la revolution franfaise.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

746 THE CHINESE BOURGEOISIE

The

boom

during the war and after, 1914-23

The war restored to the Chinese market part of the protection of which

the 'unequal treaties' of the nineteenth century had deprived it. Absorbed

in their strife, the belligerent powers turned away from China. This

European decline, which favoured the development of national indus-

tries in replacement, also encouraged the expansion of Japanese and

American interests - thus sowing the seeds of fresh difficulties and future

conflicts.

At the same time the war caused a marked increase in the world demand

for alimentary products and raw materials (non-ferrous metals, vegetable

oils).

As a major supplier of primary products China was well placed to

meet this demand. Then again, the increase in purchases made by the

Western powers in countries with a silver-based currency, such as China

and India, stimulated the rise in the international price of silver, which

had been under way since the closing of the mines in Mexico in

1913.

The

tael thus became a strong currency. Its purchasing power on Western

markets tripled within a few years. Although external debt charges were

reduced thereby, imports, and in particular the import of industrial equip-

ment, were nevertheless not facilitated; for if the war offered the Chinese

economy opportunities for development, these opportunities could be

grasped and exploited only within the restrictive framework of an 'under-

developed' economy, dependent on the dynamism of a semi-colonial

system suffering deeply from certain handicaps which themselves had

arisen from the world-wide conflict.

The requisitioning of merchant fleets by the belligerent states, the

reduction in world commercial tonnage, and the consequent rise in

freight rates hampered international trade. Exchange controls, and the

embargoes on silk and tea imposed by France and Great Britain in 1917,

denied certain traditional outlets to Chinese products. In the end the

priority given to war industries by the European powers adversely

affected the supply of equipment to China. At the moment when the les-

sening of foreign competition was stimulating the upsurge of national

industries, it became very difficult for these same industries to acquire

the machinery they needed.

6

' At the time of the First World War China

had not yet attained the level of development which would allow it to

reap the full benefit of the relative withdrawal of the foreign presence.

The difficulties caused by the war involved, it is true, a lack of profit

rather than actual losses. For the modern sector of the Chinese economy

67 TR (1915, 1917, 1919), reports from Shanghai and Canton.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE GOLDEN AGE OF CHINESE CAPITALISM 747

the years

of

warfare were

a

time

of

prosperity. However,

it

was

not

until

the

return

of

peace that

the

'golden

age'

dawned

for

the

national

business concerns.

It was not until 1919 that the modern sector began

to

reap

the

benefits

offered

by the

world

war and the

regained peace.

Far

from flagging,

the

demand

for

primary products intensified.

The

needs

of

war had

been

replaced

by

those

of

reconstruction.

In

Shanghai,

in

1919,

the

value

of

exports

was 30 per

cent higher than

the

preceding year.

The

upsurge

in

exports was

all the

more remarkable

in

that

the

price

of

silver continued

to rise,

and

with

it

the exchange rate

of

the tael. However, the urgency

of

their needs was such that European buyers were willing to pay high prices.

The greater availability

of

sea freight

and the

reconversion

of

war indus-

tries allowed

the

Chinese industrialists

to

return

to

Western markets

for

their supplies. Their purchases

of

textile material rose from

1.8

million

taels

in

1918

to

3.9

million

in

1919.

68

By an

extraordinary concatenation

of circumstances Chinese business now benefited from the demand created

previously

on the

national market

by

Western imports, from

the

relative

protection resulting from

the

decline

of

foreign competition, from

the

facilities

for the

procurement

of

supplies

on the

European and American

markets,

and

finally from

a

favourable rate

of

exchange.

After

a

moderate expansion

up

to

1917

the

value

of

foreign trade rose

from

1,040

million taels

in

1918

to

1,670

millions

in

1923. Progress

was

measured by the growth and diversification of

exports.

6

'

Imports increased

less rapidly,

but

underwent considerable restructuring: consumer

pro-

ducts,

and in

particular cotton goods,

the

manufacture

of

which

was

developing

in

China, declined

in

favour

of

hard goods, which

in

1920

represented 28.5

per

cent

of

the total value

of

Chinese purchases abroad.

70

This inequality

of

growth in imports and exports contributed

to

restoring

the balance of

trade.

In

1919 the deficit was no more than 16 million taels.

71

The composition

of

Chinese foreign trade remained that

of

an

'under-

developed' economy;

but

this trade

was no

longer exactly that

of

a de-

pendent economy:

it

corresponded, rather,

to

the

first phase

of

growth

of a modern national economy.

Stimulated

by the

demands

of

the market, both domestic

and

foreign,

production increased. Traditional sector

and

modern sector combined

to

satisfy

the new

needs.

The

scarcity

of

ocean freight

and

of

equipment,

which

had

hampered

the

upsurge

of

modern industries until 1919,

had

68

H.

G.

W.

Woodhead,

ed.

The China yearbook 1921-22, 1004-6.

69 Hsiao Liang-lin, China's foreign trade statistics, 1864-1969, 73-124.

70

Yen

Chung-p'ing, comp.

Chung-kuo

chin-tai

ching-chi shih

t'ung-chi tzu-liao

hsuan-chi

(Selected

statistical materials

on

modern Chinese economic history), 72-3.

71 Hsiao Liang-lin,

Trade

statistics,

23.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

748 THE CHINESE BOURGEOISIE

not affected the handicraft sector. From 1915-16 weaving-looms had

been increasing in number in the northern and central provinces. Produc-

tion was directed towards the domestic market. Urban workshops were

developed, and commercial capitalism spread throughout the countryside

near the major urban centres. The progress made in weaving, ready-to-

wear clothing, hosiery, glassware, matches, oil production, did not consist

merely of a resurrection of the former methods of production. Often using

improved techniques and raw materials of industrial origin (yarn, chem-

ical products), this handicraft activity represented, on the contrary, an

attempt to adapt, a particularly good example of what we referred to

above as transitory modernization. Thus we cannot subscribe to the

opinion of H. H. Fox, shared by many of his contemporaries, that 'in-

dustrial progress was limited to the most important of the treaty ports'.

72

The upsurge of modern business in the coastal cities represents only one

aspect of a more general expansion; but it is, without a doubt, the most

striking aspect. From 1912 to 1920, the growth-rate of modern industries

reached 13.8 per cent.

7

' (Such a rapid tempo of development would not

be encountered again until the days of the First Five-Year Plan, from

1953 to 1957.) The leading example was cotton yarn. The number of

spindles in the national capacity rose from 658,748 in 1919 to

1,506,634

in 1922: at that time Chinese spinners owned 63 per cent of

all

the spindles

installed in China.

74

Out of 120 spinning mills listed in 1928, 47 had been

established between 1920 and 1922. The upsurge in the food industries

is evidenced by the opening of 26 flour mills between 1917 and 1922,

75

and by the re-purchase of foreign-owned oil mills. Considerable progress

was also made in the tobacco and cigarette industry. But the enthusiasm

of the golden age scarcely spread to the heavy industries. The ephemeral

prosperity of the exploitation of non-ferrous metals (in particular an-

timony and tin) in the southern provinces was strictly determined by

international speculations, and disappeared with them. Modern coal and

iron mines remained 75 to 100 per cent controlled by foreign interests.

The most notable progress was made in the machine-building industry.

76

Shanghai and its surroundings were the main beneficiaries of this expan-

72 Department of Overseas Trade, Trade and

economic conditions

in China . . . Report by H. H.

Fox.

73 John K. Chang,

Industrial development in pre-commtmist

China:

a

quantitative

analysis.

74 Yen Chung-p'ing,

T'ung-chi

tzu-liao, 134.

75 Chou Hsiu-Iuan, Ti-i-tz'u

shih-chieh

ta-chan shih-ch'i

Chung-kuo

min-tsu

kung-yeh

ti fa-chan

(The development of national industries during the First World War; hereafter

Kung-yeh

ti

fa-chan),

ch. 2.

76 Ta-lung

chi-ch'i-ch'ang

ti

fa-shtng fa-chan

yti kai-tsao (Origin, development, and transforma-

tion of the Ta-lung Machine Works), comp. by the Academy of Sciences, Shanghai Insti-

tute for Economic Research,

et

al. Thomas G. Rawski, 'The growth of producer industries'

in Dwight H. Perkins, ed.

China's modern economy

in historical perspective, 231.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE GOLDEN AGE OF CHINESE CAPITALISM 749

sion, which also affected Tientsin

and, to a

lesser degree, Canton

and

Wuhan.

During

the

whole

of the

boom period

the

growth

of

trade

and of

production

was

sustained

by the

development

of

credit

and

stimulated

by

the

rise

in

prices

and

profits.

The

decline

of

foreign banks, which

hampered

the

operations

of

foreign trade,

did not

affect

the

domestic

market,

the

financing

of

which

had

never passed from Chinese control.

On the contrary, this domestic market made important resources available

to national businesses, such

as the

capital funds

of

notables

or

compra-

dors,

who

for

reasons

of

security

or

interest had until then chiefly funded

foreign activities.

The

rise

of

the modern Chinese banks dated from

the

First World War.

In the

years 1918

and

1919 alone,

96 new

banks were

founded.

77

However, most

of

these banks maintained close ties with

the

public authorities. This

was the

case with

the

official Bank

of

China

(Chung-kuo yin-hang)

and

Bank

of

Communications (Chiao-t'ung

yin-hang), some do2en provincial banks,

and

numerous 'political' banks

founders

of

which belonged

to

government circles

or

maintained close

relations with higher officials. The activity

of

all these establishments was

limited

to the

handling

of

state funds

and

loans.

A

dozen modern banks,

situated mostly

in

Shanghai, were

run on a

purely commercial basis;

but

their involvement in the financing of national business remained hampered

by

the

archaic structures

of the

market. Before

the war no

Chinese

ex-

change

for

securities

or

commodities

had

existed.

The

Shanghai Stock

Exchange

in the

International Settlement only handled foreign stocks.

The creation

and

success

of

the Shanghai Stock

and

Produce Exchange

(Shang-hai cheng-ch'iian wu-p'in chiao-i

so)

inspired many imitations.

At the end

of

1921

Shanghai had 140 establishments, most

of

which traded

only

in

their

own

shares until

a

general collapse,

the

stock exchanges

crash (hsin-chiao feng-cW

ao),

put an end some months later to this mushroom

growth.

7

'

In order

to

finance businesses,

the

modern banks were thus obliged,

just like

the

old-style banks

(ch'ien-chuang),

to

resort

to

direct loans. How-

ever,

the

modern banks demanded guarantees from their clients

in the

form

of

property mortgages

or

deposits

of

goods. This

put

them

at a

disadvantage vis-a-vis

the

ch'ien-chuang

which, operating under customary

rules

and on a

basis

of

personal relations, granted loans

'on

trust'.

Con-

sequently, despite

the

spectacular

but

essentially speculative rise

of the

modern banking sector,

the

real business banks remained

the

ch'ien-

77

D. K.

Lieu,

China's industries

and

finance,

48.

78 Sha Yao-shu, 'Lun chiao-i-so chih shih-pao yuan-yin' (The causes

of

failure

of

the Chinese

exchanges), TSHYP,

2. 8

(Aug. 1922)

8-IJ.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

7JO THE CHINESE BOURGEOISIE

chuang.

In

Shanghai there were 71

of

them

in

1920 (as against 31

in

1913),

and

the

capital they controlled

- 7.7

million Chinese dollars

- was

five

times greater than that

on the eve of

the world

war.

In

the

absence

of a

stock exchange market

and of a

national discount

system,

a

useful barometer

of

economic progress was

the

interest rate

on

inter-bank loans

on the

Shanghai market

(yin-c/ie).

The

monthly average

rose from 0.06 (one candareen

per

day

per 1,000

taels)

in

1919

to

0.17

in

1922.

Although this rise

in the

cost

of

money

can be

explained

as

being

due

to

purely financial reasons (repatriation into

the

metropolis

of the

bullion reserves

of the

foreign banks, speculative purchases

of

gold

on

the world market), there

is no

doubt that

the

needs

of an

expanding

economy played their part: for example, the marketing of crops earmarked

for export involved larger and larger capital levies on the financial markets

of the

big

cities.

Constructed according

to

various methods

and

based upon hetero-

geneous surveys, the available price-indices did

not

permit

of

very precise

analyses.

79

They did, however, show

a

rise

in

wholesale prices during

the

First World

War

from

20 to 44 per

cent. This development, which

was

quite moderate

in

comparison with that

in

Western countries during

the

same period, was due

to

the stability

of

agricultural prices

in

contrast with

the soaring

of

industrial costs.

In a

traditional rural economy this stability

of agricultural prices (from which, however,

the

prices

of

certain export

products were excluded) was evidence less

of

the stagnation

of

the market

than

of

the favourable character

of

the climatic conditions

-

that

is, the

relative equilibrium

of

the rural world. The stability

of

agricultural prices

and

the

rise

in

industrial prices were

to be

seen

as

complementary signs

of prosperity.

It

was

above

all the

business world that profited from this prosperity.

From 1914

to

1919

the

average profit

for

cotton-spinning mills

per

ball

of yarn rose

by 70 per

cent,

and

that

of

the

ch

y

ien-chuang

by 74 per

cent.

80

The most important companies increased their profits twenty-fold, some

even fifty-fold. Dividends reached 30

to

40

per

cent,

and

sometimes even

90

per

cent.

8

'

The

gains

of

the businessmen were

all the

more significant

in that they hardly shared them

at all

with their employees: indeed,

the

79 Nan-k'ai ta-hsueh ching-chi yen-chiu

so

(Nankai Institute

for

Economic Research) comp.

ifi) nien-if/2 men Nan-k'ai

chih-shu tzu-liao hui-pieri)

(Nankai price indexes 1913-1952),

2-7;

'Methods

of

price investigation', The

Chinese economic

bulletin,

21

June

1924.

80 Yen Chung-p'ing, Tung-chi

tzu-liao,

table

6i, p.

165;

Shang-haicKien-chuangshih-liao

(Material

for the history

of

the

ch'ien chuang

banks

of

Shanghai), comp. Chung-kuo jen-min yin-hang

Shang-hai-shih fen-hang (The Shanghai branch

of

the Chinese People's Bank), 202.

81

Cf.

the case

of

the Ta-sheng spinning-mills cited by Samuel Chu,

Reformer in modem

China,

Chang Chien

i8j}-i9i6, 31.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE GOLDEN AGE OF CHINESE CAPITALISM 75 I

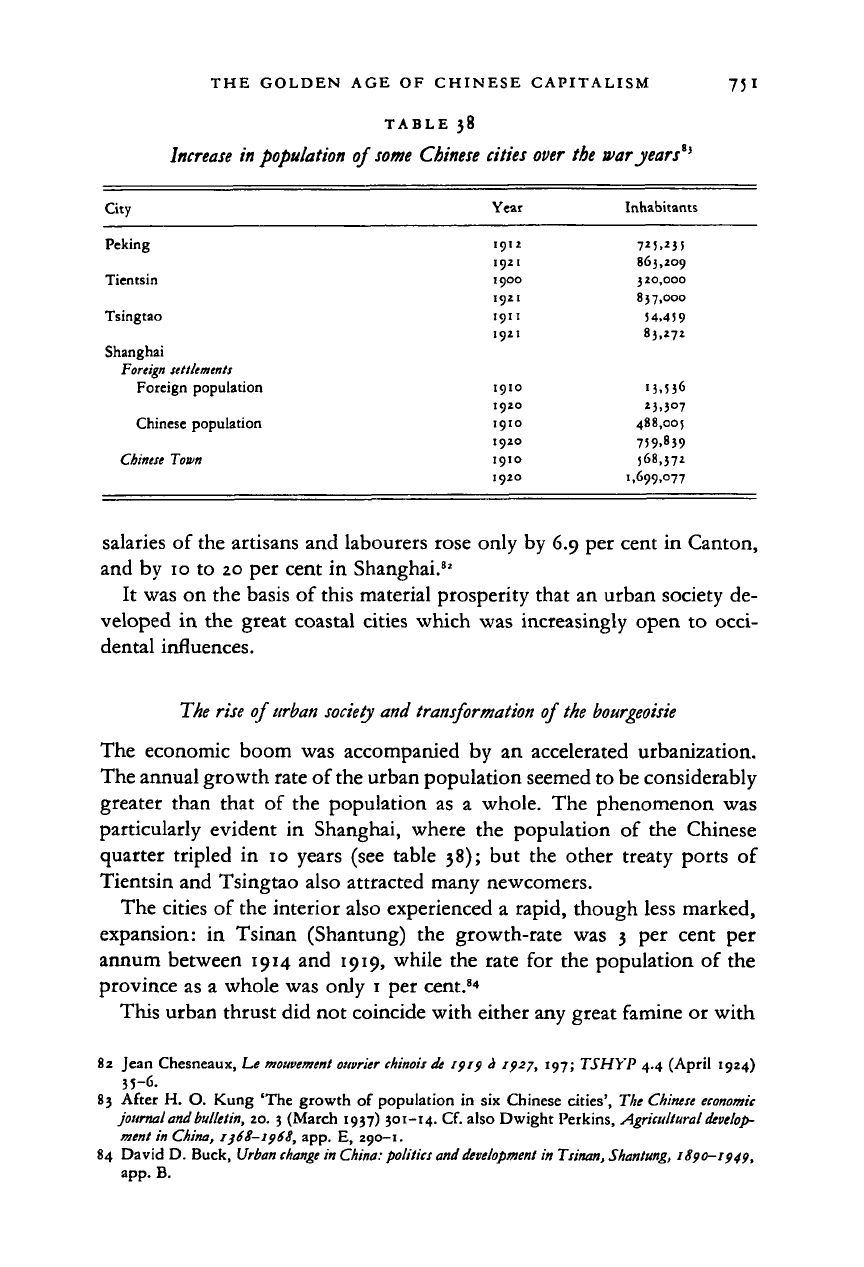

TABLE 38

1912

1921

1900

1921

1911

1921

1910

1920

1910

1920

1910

1920

7*5.235

863,209

320,000

837,000

54.459

83.*7*

'3.536

*3.3°7

488,00;

759.839

568,572

1,699,077

Increase

in population

of

some Chinese

cities

over

the

war years

1

*

City Year Inhabitants

Peking

Tientsin

Tsingtao

Shanghai

Foreign settlements

Foreign population

Chinese population

Chinese Town

salaries

of

the artisans

and

labourers rose only

by 6.9 per

cent

in

Canton,

and

by 10 to 20 per

cent

in

Shanghai.

82

It

was on the

basis

of

this material prosperity that

an

urban society

de-

veloped

in the

great coastal cities which

was

increasingly open

to

occi-

dental influences.

The rise

of

urban society

and

transformation

of

the

bourgeoisie

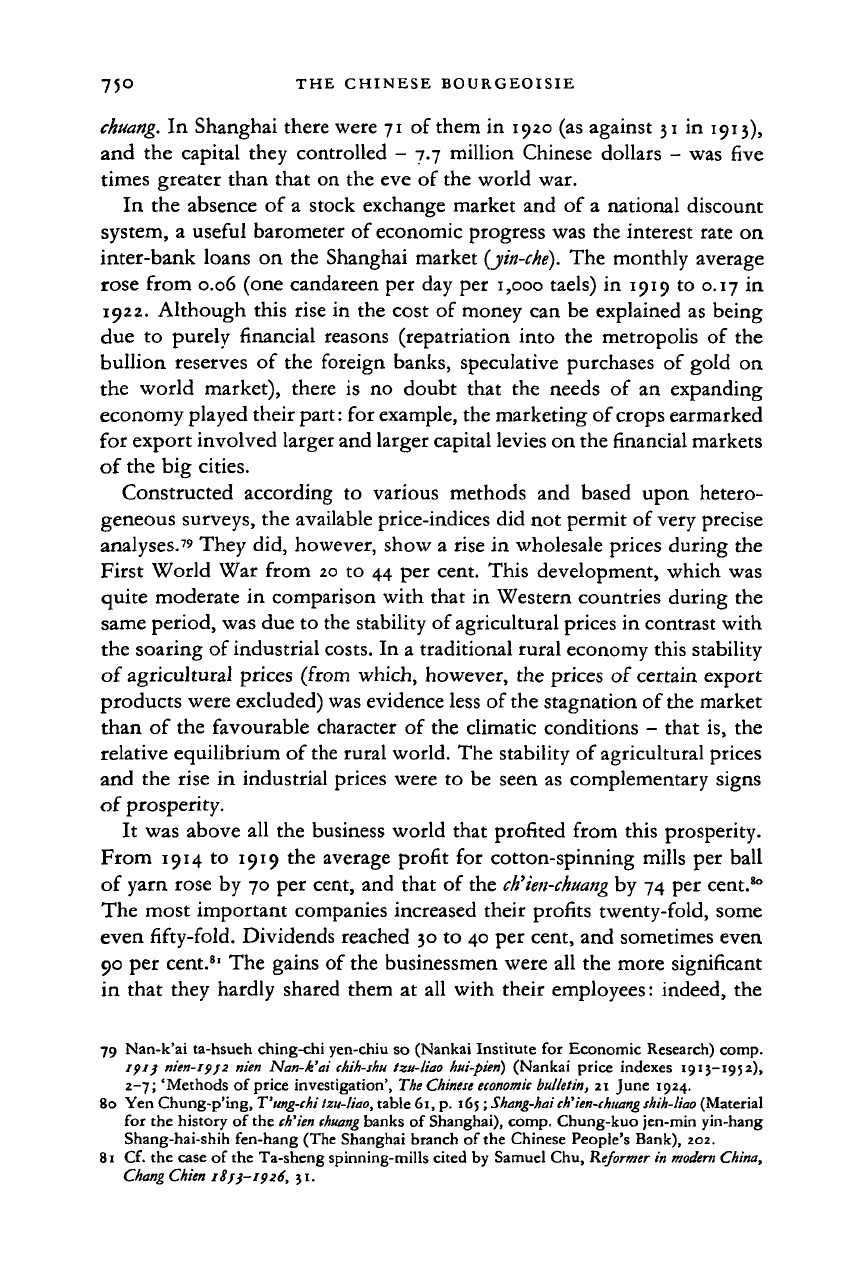

The economic boom

was

accompanied

by an

accelerated urbani2ation.

The annual growth rate of the urban population seemed

to

be considerably

greater than that

of the

population

as a

whole.

The

phenomenon

was

particularly evident

in

Shanghai, where

the

population

of the

Chinese

quarter tripled

in 10

years

(see

table

38); but the

other treaty ports

of

Tientsin

and

Tsingtao also attracted many newcomers.

The cities

of

the interior also experienced

a

rapid, though less marked,

expansion:

in

Tsinan (Shantung)

the

growth-rate

was 3 per

cent

per

annum between 1914

and

1919, while

the

rate

for the

population

of the

province

as a

whole was only

1

per

cent.

84

This urban thrust

did not

coincide with either any great famine

or

with

82 Jean Chesneaux,

Le

mouvement ouvrier chinois

de rfif

a 1927, 197;

TSHYP

4.4

(April

1924)

35-6.

83 After

H. O.

Kung

'The

growth

of

population

in six

Chinese cities', The

Chinese economic

journal and

bulletin,

20. 3 (March 1937) 301-14.

Cf.

also Dwight Perkins, Agricultural

develop-

ment

in

China, 1)68—1968, app.

E,

290-1.

84 David

D.

Buck,

Urban change

in

China:

politics and

development

in

Tsinan, Shantung,

app.

B.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

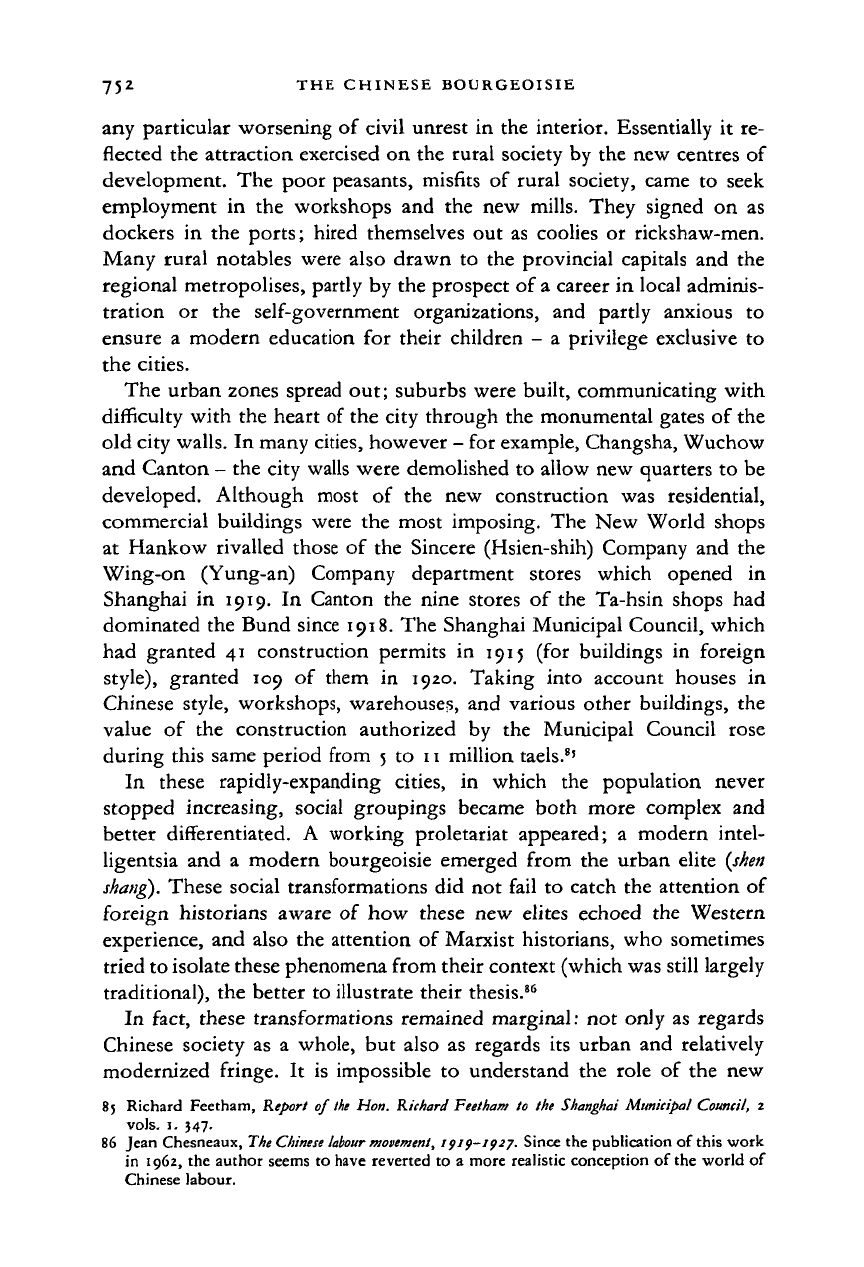

75*

THE CHINESE BOURGEOISIE

any particular worsening

of

civil unrest

in

the interior. Essentially

it

re-

flected the attraction exercised on the rural society by the new centres of

development. The poor peasants, misfits

of

rural society, came

to

seek

employment

in the

workshops and

the

new mills. They signed

on as

dockers

in

the ports; hired themselves out as coolies

or

rickshaw-men.

Many rural notables were also drawn

to

the provincial capitals and the

regional metropolises, partly by the prospect of a career in local adminis-

tration

or the

self-government organizations,

and

partly anxious

to

ensure

a

modern education

for

their children

- a

privilege exclusive

to

the cities.

The urban 2ones spread out; suburbs were built, communicating with

difficulty with the heart of the city through the monumental gates of the

old city walls. In many cities, however

-

for example, Changsha, Wuchow

and Canton

-

the city walls were demolished to allow new quarters to be

developed. Although most

of the new

construction

was

residential,

commercial buildings were the most imposing. The New World shops

at Hankow rivalled those

of

the Sincere (Hsien-shih) Company and the

Wing-on (Yung-an) Company department stores which opened

in

Shanghai

in

1919.

In

Canton the nine stores

of

the Ta-hsin shops had

dominated the Bund since 1918. The Shanghai Municipal Council, which

had granted 41 construction permits

in

1915

(for

buildings

in

foreign

style),

granted

109 of

them

in

1920. Taking into account houses

in

Chinese style, workshops, warehouses, and various other buildings,

the

value

of the

construction authorized

by the

Municipal Council rose

during this same period from 5

to

11 million taels.

8

'

In these rapidly-expanding cities,

in

which

the

population never

stopped increasing, social groupings became both more complex

and

better differentiated.

A

working proletariat appeared;

a

modern intel-

ligentsia and

a

modern bourgeoisie emerged from the urban elite

(shen

shang).

These social transformations did not fail

to

catch the attention of

foreign historians aware

of

how these new elites echoed

the

Western

experience, and also the attention

of

Marxist historians, who sometimes

tried to isolate these phenomena from their context (which was still largely

traditional), the better to illustrate their thesis.

86

In fact, these transformations remained marginal: not only as regards

Chinese society

as a

whole, but also

as

regards

its

urban and relatively

modernized fringe.

It is

impossible

to

understand the role

of

the new

85

Richard Feetham, Report

of

the

Hon. Richard Feetham

to

the Shanghai Municipal Council,

z

vols.

1.

347.

86 Jean Chesneaux, The

Chinese labour

movement,

1919-1927. Since the publication of this work

in 1962, the author seems

to

have reverted

to a

more realistic conception

of

the world of

Chinese labour.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008