?tekauer Pavol, Lieber Rochelle. Handbook of Word-Formation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

W

OR

D

-

F

ORMATION AND INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

55

For example, virtuall

y

ever

y

nonmodal verb in En

g

lish has a nominal derivative in

-in

g

.

For these reasons, criterion (B) cannot be plausibl

y

seen as providin

g

either a

n

ecessar

y

or a sufficient correlate of th

ed

i

s

tin

c

ti

o

n

be

t

wee

n infl

ec

ti

o

n an

d

wo

r

d

-f

o

rmati

o

n

.

Another criterion for distinguishing inflection from word-formation is that of

semantic regularit

y

:

(C) Inflectional operations tend to be semanticall

y

re

g

ular, while

o

perations of word-formation are frequentl

y

less than full

y

re

g

ular in

th

e

ir

se

manti

ce

ff

ec

t

.

B

y this criterion, the inflectional expression of a particular set of morphosyntactic

properties has the same semantic effect from one lexeme to another. For instance,

the meanin

g

expressed b

y

the past-tense inflection of

sang

is identical to that

g

expressed b

y

the past-tense inflection of

b

r

oke

.

B

y

contrast, operations of

word-formation often express meanin

g

s that are at least partiall

y

unpredictable.

C

onsider, for exam

p

le, the words

ba

r

numi

z

e

,

dolla

r

i

z

e

,

and

p

osteriz

e

(

all recent

additions to the lexicon of English): even if one knows the meanings of B

a

r

num

,

dolla

r

,

and

p

oste

r

and possesses a native command of the rule forming denominal

r

ve

r

bs

in -

i

z

e

,

these do not suffice to allow one to deduce the meanings of these

ve

r

bs: bec

a

use

th

e

-

i

z

e

rule underdetermines the meanings of denominal verbs in

-

i

z

e

,

one must simply infer the meaning of each

suc

h

ve

r

bw

h

e

n

o

n

e

fir

s

t h

e

ar

s

it an

d

s

tore this meanin

g

in lexical memor

y

for later use

.

4

A

lthou

g

h (C) seems to be a valid criterion in such cases, other instances cast

doubt on its reliability. Operations which ma

y, by other criteria, be unequivocally

a

a

c

lassified as instances of word-formation sometimes show high semantic regularity;

for instance, adverbs arising from adjectives through the suffixation of -

ly

generally

h

ave the meaning “in an X manner”, where the adjectival base supplies the meaning

X. By the same token, operations which otherwise seem to be inflectional do

o

ccasionally show semantic irregularity; for instance, as a plural form of

b

r

othe

r

,

b

r

eth

r

en

has an idiosyncratic meaning distinct from that of

b

r

othe

r

s

. Like

(

B

)

,

c

riterion (C) affords neither a necessar

y

no

r

a

su

ffi

c

i

e

nt

co

rr

e

lat

eo

f th

ed

i

s

tin

c

ti

o

n

be

t

wee

n infl

ec

ti

o

n an

dwo

r

d

-f

o

rmati

o

n

.

T

he most robust criterion for distinguishing inflection from word-formation is

th

ec

rit

e

ri

o

n

o

f

s

yntactic relevance

:

(

D) Inflection, unlike word-formation, is syntactically determined.

A

ccording to this criterion, a particular syntactic context may necessitate the

c

hoice of a

p

articular inflected form, but

n

o syntactic context ever necessitates the

c

hoice of a form arising as the effect of a particular word-formation operation. Fo

r

i

nstance, the phrasal context [

e

ver

y

___ ] requires the choice of a head noun

4

To barnumize something is to publicize it hyperboli

c

ally, to dollarize one’s economy is to convert it to

o

ne based on the American dollar

,

and to posterize one’s opponents is to humiliate the

m

o

stentatiousl

y

.

56

G

REGORY

T

.

ST

U

MP

i

nflected for singular number; any verb in the phrasal context [

hasn

’

t

___ ] must be

t

i

nflected as a past participle; and any adverb in the phrasal context [ ___

than ever

]

r

m

ust be inflected for comparative degree.

B

y contrast, there is no syntactic context

t

hat is restricted to forms defined b

y

a particular word-formation operation; thus, an

y

s

y

ntactic context allowin

g

the morpholo

g

icall

y

complex noun

teacher

allows the

r

m

orpholo

g

icall

y

simplex noun

friend

,

an

y

allowin

g

the complex verb proo

f

read

allows the sim

p

lex verb

edit

,

and any allowing the complex adverb extremel

y

all

ows

t

he sim

p

lex adverb

v

er

y

.

C

riterion

(

D

)

holds true because

p

articula

r

syntactic contexts are associated with

particular sets of morphosyntactic prope

r

t

ies

,

and such contexts necessitate the

i

nflectional expression of the morphosyntactic properties with which they are

associated. Even so,

(

D

)

raises a

q

uestion

.

Is s

y

ntactic determination a necessar

y

propert

y

of inflectional contrasts, or do so

me

infl

ec

ti

o

nal

co

ntra

s

t

s

fail t

oco

rr

e

lat

e

s

y

stematicall

y

with differences of s

y

ntactic context? This is a si

g

nificant question,

since syntactic context may, for example, fail to determine choices among tense

i

nflections: thus, in English, it is not clear that there is any syntactic context that

n

ecess

itat

es

th

ec

h

o

i

ce o

f

o

n

e

t

e

n

se ove

r an

o

th

e

r

.

5

One might regard this as evidence

against regarding tense as an inflectional category in English, but this isn’t a

necessary conclusion. There are syntactic c

o

ntexts which require the use of a finite

v

erb form (for instance, subordinate clauses introduced by the complementizers

that

an

d

if

m

ust have finite verbs), and an En

g

lish verb form is finite if and onl

y

if it

belon

g

s to one or the other tense; thus,

o

ne could sa

y

that tense is s

y

ntacticall

y

d

etermined in En

g

lish insofar as the pres

e

nce of a tense propert

y

is a necessar

y

and

su

ffi

c

i

e

nt

co

rr

e

lat

eo

f finit

e

n

ess.

A

final, widely-cited criterion for distinguishing inflection from word-formation

i

s (E); this is often seen as a corollary of assumption (

E

ƍ

).

(

E) In the structure of a

g

iven word, marks of inflection are peripheral to

m

ark

so

f

wo

r

d

-f

o

rmati

o

n

.

(

E

ƍ

) In the definition of a word’s morphology, derivational operations

appl

y

before inflectional operations.

A

ccording to (E)/(

E

ƍ

)

, an inflectional affix should never be able to be situated

be

t

wee

n a

s

t

e

m an

d

a

de

ri

v

ati

o

nal affix

.

A

lthough this generalization is apparently

s

atisfied by most English words (one cannot, after all, say

*

a thornsy plant

o

r

t

*

seve

r

al shoesless child

r

en

), there do seem to be occasional counterexamples, such

a

s

worsen

or

bette

r

ment

(counterexamples if degree morphology is inflectional) or

t

suc

h

d

ial

ec

tal f

o

rm

s

a

s

scareder

and

r

rockin

’

est

(counterexamples if degree

t

m

orpholo

gy

is derivational). Other l

a

ng

ua

g

es, however, provide more robust

cou

nt

e

r

ev

i

de

n

ce.

5

Tense choice may, of course, be determined by semantic considerations, as in #

I left tomorrow

#

#

,

but that

is

n

o

t th

e

i

ssue

h

e

r

e.

W

ORD

-

FORMATION AND INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

5

7

In Breton, for example, affixall

y

i

nflected plurals are sub

j

ect to

c

ate

g

or

y

-chan

g

in

g

derivational processes. Thus, each of the denominal derivatives

i

n Table 2 has a

p

lural noun as its base

(

Stum

p

1990a,b

).

6

Moreover

,

Breton has a

p

roductive

p

attern for the formation of

p

lural diminutives in which two ex

p

onents of

p

lural number a

pp

ear, one on either side of the diminutive marker:

b

ag

-

où

-

ig

-

où

‘little boats’ [‘boat-PL

U

RAL

-

DIMIN

U

TIVE

-

PL

U

RAL

’

];

p

arallel formations fo

r

diminutives or augmentatives appear in a number of languages, e.g. Kikuyu (

t

NJ

m

ƭ

t

ƭ

ƭ

ƭ

‘little trees’; Stump 1993), Portuguese (

animai

z

inhos

‘little animals’; Ettinger 1974:

60

)

, Shona

(

ma

z

iva

r

ume

‘big men’; Stump 1991), and Yiddish (

xasanimlex

(

(

‘littl

e

bride

g

rooms’; Bochner 1984, Perlmutter 1988).

B

efore dismissin

g

such examples as hi

g

hl

y

-marked exoticisms, one shoul

d

l

ikewise note that marks of word-formation appear peripherally to marks of

i

nflection as an effect of morphological head-marking in a vast number of languages

(

Stum

p

1995; 2001: Cha

p

ter 4

)

. Consider, for exam

p

le, the Sanskrit verb ste

m

ni

-

pat-

-

‘fly down’: because this ste

m

is headed by the root pa

t-

‘fly’, it inflects

t

hrough the inflection of its head; thus, in the imperfect for

m

ny

-

a

-

patat

-

‘s/

h

e

fl

ew

down’

,

the tense marke

r

a-

i

s prefixed directly to the root, and is therefore

positioned internall

y

to the preverb

ni

-. Cases of this sort are le

g

ion; indeed, En

g

lish

i

tself furnishes exam

p

les in forms such as

mothe

r

s

-

in

-

law

,

han

g

ers

-

on

,

understood

,

and the purportedl

y

paradoxical unha

pp

ier (Stump 2001: Chapter 8; concernin

g

unha

pp

ier

,

cf. Pesetsky (1985), Sproat (1988), and Marantz (1988)). Examples of this

s

ort are, if anything, more devastating than those of Table 2 for the tenability of

c

riterion

(

E

)

or assum

p

tion

(E

ƍ

): counterexamples such as those in Table 2 generally

i

nvolve inherent but not contextual inflection; but instances of head-marking may

i

nvolve either type of inflection. This evidence is of considerable theoretical

s

ignificance, since assumption (E

ƍ

)

has sometimes been elevated to the status of a

principle of

g

rammatical architecture

,

in the form of the

S

plit Morpholo

gy

H

y

pothesis

(

Perlmutter 1988; cf. Anderson 1982

)

.

The criteria in (A)-(E) distin

g

uish inflection from word-formation accordin

g

to

their synchronic grammatical behavior; but this distinction also has correlates in the

diachronic domain. For instance

,

inflected fo

r

ms of the same lexeme are more likely

to influence one another analo

g

icall

y

than forms standin

g

in a derivational

r

elationship; thus, although the intervocalic rhotacism o

f

s

in the inflection of early

L

atin

hon

ǀ

s-

ǀ

ǀ

‘honor’ (sg. nom.

hon

ǀ

s

ǀ

ǀ

but gen.

hon

ǀ

r

-

is

,

dat.

hon

ǀ

r-

Ư

, acc.

Ư

Ư

hon

ǀ

r

-

em

,

e

tc.) leads to the analo

g

ical nominative sin

g

ular for

m

honor

in Classical Latin, no

r

s

uch analogical development takes place in

t

he inflection of the derived adjective

hones

-

tus

‘honored’, which preserves its stem-final

s

. Such instances provide

c

ompellin

g

evidence for the ps

y

cholo

g

ical realit

y

of the distinction between

i

nflection from word-formation

,

but are o

f

limited value as practical criteria for

f

delineating this distinction because of

their inevitably anecdotal character.

f

Ps

y

cholin

g

uistic criteria for distin

g

uishin

g

inflection from word-formation are also

6

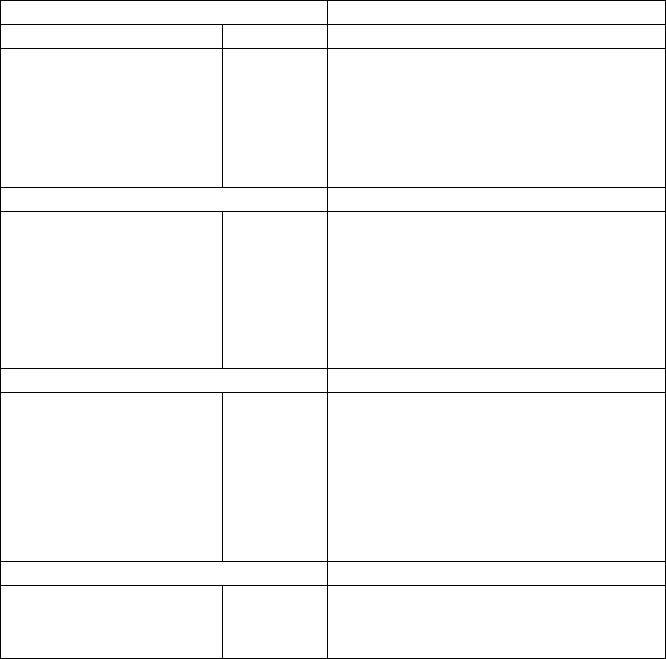

In Table 2

,

verbs in infinitival -

i

and adjectives in -

ek

exhibit a strengthening of

k

ou

t

o

aou

in t

o

ni

c

(penultimate) position; verbs in infinitival -

a

exhibit the devoicing of a final obstruent in their nominal

base; and privative ad

j

ectives in

di

-e

xhi

b

it initial l

e

niti

o

n

o

f th

e

i

r

n

o

minal

b

a

se.

All

o

f th

ese

m

odifications are independentl

y

observable in Breton.

58

GREGORY

T

.

S

T

U

M

P

s

omewhat problematic: experimental evidence su

gg

ests that inflected forms are

o

ften analyzed online while derived forms and compounds are instead simply stored

whole in memory; but irregularly inflected forms likewise give evidence of being

s

tored whole, as do hi

g

h-frequenc

y

forms

e

xhibitin

g

re

g

ular i

n

flection

(

Aitchison

1994: 122ff). The utility of psycholinguistic c

r

i

teria is further mitigated by the fact

t

hat the experimental studies on which they are based have tended to focus on the

m

orpholo

g

ical s

y

stems of European lan

g

ua

g

es, which fall far short of instantiatin

g

t

he full range of morphological types found in human language.

N

ou

n D

e

n

o

minal

de

ri

v

ati

ve

Singular Plural Verbs in infinitival

–

i

ba

r

r

‘rain shower’

r

ba

rr

où ba

rr

aoui

‘to shower (rain)’

i

delienn

‘l

e

af’

delioù deliaoui

‘grow leaves’

i

and

dizeliaoui

d

‘pull leaves from’

i

p

ilhenn ‘ra

g

’

p

ilhoù

p

ilhaou

i

‘collect rags, go

i

doo

r-t

o

-

doo

r’

preñv

‘worm’

v

p

reñved

p

reñvedi ‘become wormy’

V

erbs in infinitival –

a

goz

‘mole’

z

g

ozed

g

ozeta ‘t

o

h

u

nt f

o

r m

o

l

es

’

gwrac’h ‘

w

ra

sse

’

gwrac’hed gwrac’heta

‘t

o

fi

s

h f

o

r

w

ra

sses

’

k

r

ank

‘crab’

k

kranked kranketa

‘to fish for crabs’

labous

‘

b

ir

d

’

laboused labouseta

‘t

o

h

u

nt

b

ir

ds

’

me

r

c

’

h

‘girl’

merc’hed merc’heta

‘to chase girls’

pesk

‘fish’

k

pesked pesketa

‘t

o

fi

s

h’

Ad

j

ectives i

n

–ek

delienn

‘l

e

af’

delioù deliaouek

‘leafy’

k

d

r

aen

‘th

o

rn’

drein dreinek

‘thorny’

k

ko

r

n

‘h

o

rn’

ke

r

niel ke

r

niellek

‘having horns’

k

maen

‘r

oc

k’

mein meinek

‘full of rocks’

k

preñv

‘worm’

v

preñved preñvedek

‘wormy’

k

sp

ilhenn ‘

p

in’

sp

ilhoù s

p

ilhaoue

k

‘having pins’

k

t

r

uilhenn

‘rag’

t

r

uilhoù t

r

uilhaouek

‘raggedy’

k

Privative ad

j

ectives i

n

di

-

boutez

‘shoe’

z

boutoù divoutoù

‘

s

h

oe

l

ess

’

d

r

aen

‘th

o

rn’

d

r

ein di

zr

ein

‘having no thorns’

loer

‘sock’

r

le

r

où dile

r

où

‘

soc

kl

ess

’

T

a

b

l

e

2 Denominal derivatives based on inflected plurals

i

n Breton (Stump 1990a,b)

W

ORD

-

FORMATION AND INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

59

4

. PRA

C

TI

C

AL

C

RITERIA F

O

R DI

S

TIN

GU

I

S

HIN

G

INFLE

C

TI

O

NAL

PERIPHRA

S

E

S

I

f periphrasis is re

g

arded as a mode o

f

m

orpholo

g

ical expression, as su

gg

ested in §2

above, then criteria for distinguishing periphrases (morphologically defined word

combinations) from ordinary, syntactically

defined word combinations must be

y

i

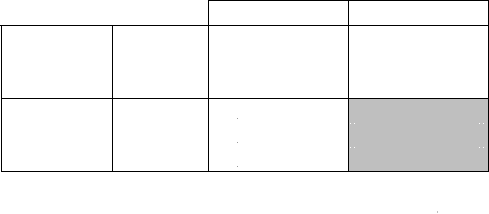

dentified. Ackerman & Stump (2004) propose three such criteria. The first of these is

t

hat

of

featural intersectiveness

f

:

(F) If an anal

y

tic combination C has a featurall

y

intersective distribution,

t

hen C is a periphrase.

C

riterion (F) entails that if the intersection of properties P and Q is always expressed

by an analytic combination C even though neither P nor Q is always expressed

analytically on its own, then C is a periph

r

ase. In Latin, for example, the intersection

o

f the properties ‘perfect’ and ‘passive’ is always expressed by analytic

c

ombinations such as those in the shaded cells of Table 3

;

on the other hand

,

neithe

r

‘perfect’ nor ‘passive’ is alwa

y

s expressed anal

y

ticall

y

on its own. For this reason,

t

h

e

f

o

rm

s

in th

es

ha

ded ce

ll

s

in Ta

b

l

e

3 are periphrases b

y

criterion (F).

Ta

b

l

e

3

1

st-person plural indicative forms of Latin

CAPI

ƿ

I

I

‘

take

’

The second criterion of

p

eri

p

hrastic status is that of

n

oncompositionalit

y

:

(G) If the property set associated with an analytic combination C is not the

c

omposition of the property sets associated with its parts, then C is a

p

eri

p

hrase.

C

riterion (G) entails that analytic combinations whose property sets are not

d

educible from those of their

p

arts are

pe

r

i

p

hrases. In French, for exam

p

le, the

forms of the passé composé are preterite in

t

ense, as their appearance with past-tense

t

im

e

a

dve

r

bs s

h

ows:

H

ier j’ai chanté

.

Yet, they are formed with an auxiliary

i

nflected for present tense and a participle that is uninflected for tense

;

forms of the

passé composé are therefore periphrases b

y

criterion (G).

The third criterion of

p

eri

p

hrastic status is that of

d

istributed ex

p

onenc

e

:

A

c

ti

ve vo

i

ce

Pa

ss

i

ve vo

i

ce

Nonper

f

ect Present capimus capimur

Pa

s

t ca

p

i

Ɲ

b

Ɨ

m

us ca

p

i

Ɲ

b

Ɨ

mur

F

u

t

u

r

e

ca

p

i

Ɲ

mus capi

ƝƝ

Ɲ

mu

r

Ɲ

Ɲ

P

e

r

fec

t Pr

ese

nt

c

Ɲ

pimus

ƝƝ

ca

pt

Ư

sumus

Ư

Pa

s

t

c

Ɲ

per

ƝƝ

Ɨ

mus

ca

pt

Ư

e

r

Ư

Ɨ

mus

F

u

t

u

r

e

c

Ɲ

perimus

ƝƝ

cap

t

Ư

erimus

Ư

60

GREGORY

T

.

S

T

U

M

P

(

H) If the property set associated with an analytic combination C has its

exponents distributed among C’s parts, then C is a periphrase.

C

riterion (H) entails that an anal

y

tic combination is a periphrase if its

m

orphosyntactic properties are an amalgamation of the properties of its parts. In

U

dmurt, for example, each of the neg

a

t

i

ve

f

u

t

u

r

e

-t

e

n

se

r

e

alizati

o

n

so

f

M

Ï

N

Ï

‘go’ in

Table 4 is the periphrastic combination of a form of the negative verb

U

w

ith a

special ‘connegative’ form of

MÏ

N

Ï

f

; the latter expresses number but not person, while

t

he former expresses person but not number – except in the first person, where

ug

an

d

um

express both person and number (Ackerman & Stump 2004).

Sin

g

ular 1

s

t

u

g

m

ï

n

ï

2

n

d

ud mïnï

3

rd

u

z

mïnï

Pl

u

ral

1

s

t

um mïne

(

le

)

2

n

d

ud mïne

(

le

)

3

rd

uz mïne

(

le

)

Ta

b

l

e

4 Ne

g

ative

f

uture-tense

f

orms o

f

Udmur

t

MÏNÏ

‘g

o

’

(

Csúcs 1988: 143

)

A

ll thr

ee o

f th

ec

rit

e

ria i

n

(

F

)

-

(

H

)

are sufficient indicat

o

rs of

p

eri

p

hrastic status,

but none is necessary. Further research into the nature of

p

eri

p

hrasis will therefore

be needed to identify and refine the range of criteria used to distinguish word

c

ombinations that are morphologically defined from those that are syntactically

d

efined. Correspondingly, a more carefully articulated theory of lexical insertion

m

ust be devised to accommodate the assump

t

ion that a lexeme’s realizations may

i

n

c

l

ude wo

r

dco

m

b

inati

o

n

s

a

swe

ll a

s

in

d

i

v

i

du

al

wo

r

ds.

5

.

SO

ME

S

IMILARITIE

S

BET

W

EEN INFLE

C

TI

O

N AND

W

ORD-FORMATION

Notwithstanding the clarity of the conceptual distinction between inflection and

word-formation (section 1) and the man

y

practical criteria that are invoked to

d

istin

g

uish inflectional operations from op

e

r

ations of word-formation

(

section 3

)

,

t

he boundar

y

between inflection and word-formation can, in fact, seem quite elusive,

f

o

r a n

u

m

be

r

o

f r

e

a

so

n

s.

7

Most obviously, the formal operations by which words are

i

nflected are not distinct from those by which new words are formed. Indeed

,

the

v

ery same marking may serve as an infl

e

ctional ex

p

onent in one context and as a

m

ark of derivation in another; thus, the present participle

reading

in

g

I am reading

i

s

g

an infl

ec

t

ed

f

o

rm

o

f

R

EA

D

,

but the noun READIN

G

in the assigned readings i

s

a

7

Indeed

,

some researchers have concluded that

t

here are no good grounds for distinguishing inflection

from word-formation in morphological theory; see

e

.g. Lieber (1980: 70), Di Sciullo & Williams

(

1987: 69ff

)

, and Bochner

(

1992: 12ff

)

.

W

ORD

-

FORMATION AND INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

6

1

de

ri

v

ati

ve o

f

R

EA

D

.

More

g

enerall

y

, both the domain of inflection and that of

word-formation involve affixation, se

g

me

n

t

al and suprase

g

mental modifications,

and identit

y

operations; both

i

nvolve relations of su

pp

l

e

tion, s

y

ncretism, and

periphrasis; just as an inflected form may

i

nflect on its head, so a derived form may

c

arry its mark of derivation on its head; and just as an inflected form that is lexically

l

isted may ‘block’ an inflectional alternative, so a derivative that is lexically listed

m

ay block a derivational alternative. Examples illustrative of these parallelisms are

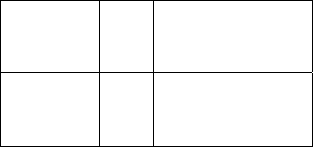

l

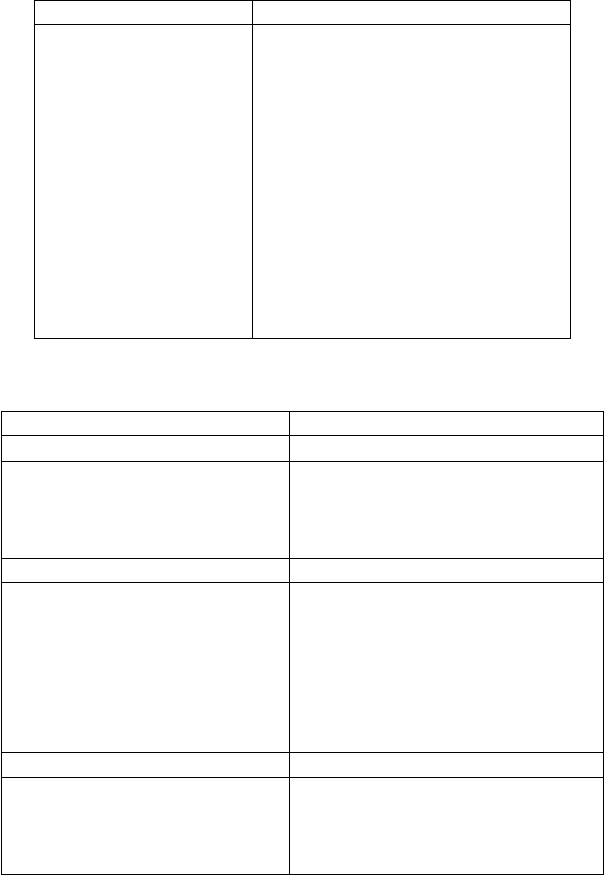

i

s

t

ed

in Ta

b

l

e

5

.

T

a

b

l

e

5

P

arallelisms between inflection and word-formation

6

.

CO

MPLEX INTERA

C

TI

O

N

S

BET

W

EEN INFLE

C

TI

O

N AND

WO

RD-F

O

RMATI

O

N

The task of distin

g

uishin

g

inflection and word-formation is further complicated

b

y

the various wa

y

s in which the two sorts of morpholo

gy

ma

y

interact. As was seen

i

n section 3, o

p

erations of word-formati

o

n tend to

p

recede inflectional o

p

erations in

the definition of a word’s morphology, but word-formation operations sometimes

apply to inflected forms; thus, one cannot assume that rules of word-formation and

r

ules of inflection are situated in distinct grammatical components such that one

s

imply feeds the other.

Moreover

,

there are instances

i

n which a lexeme’s derivative is incorporated into

that lexeme’s inflectional paradigm. Consider a case of this sort from Breton. One of

the distinctive characteristics of Breton morpholo

gy

is its hi

g

hl

y

productive suffix

-

enn

. One of its functions is as a sin

g

ulative suffix: it

j

oins with a collective noun to

produce a noun with sin

g

ular reference, as in Table 6. In add

i

tion

,

-

enn

j

oins with

Operation

o

r r

e

lati

o

n

I

nfl

ec

ti

o

nal

do

main

D

o

main

o

f

wo

r

d

-f

o

rmati

o

n

A

ffixati

o

n

bake

ĺ

bake

-

s

bake

ĺ

bak

-

k

k

e

r

Se

g

mental

m

od

ifi

c

ati

o

n

s

in

g

ĺ

s

an

g

house

ĺ

hou

[

z

]

e

Suprasegmental

m

od

ifi

c

ati

o

n

No English examples, but

cf. e.g. Somali

díbi

‘

bu

ll’

ĺ

dibí

‘

bu

ll

s

’

r

ej

é

c

t

ĺ

r

ejec

t

I

dentity operation

deer

(sg.)

r

ĺ

deer

(pl.)

r

cook

(v.)

k

ĺ

cook

(n.)

k

Suppletion

sad

ĺ

sadder

but

r

bad

ĺ

wo

r

se

presiden

t

ĺ

presidential

bu

t

l

governor ĺ

g

ubernatorial

S

y

ncretis

m

walked

(past tense) =

d

walked

(past participle)

d

Mexican

(ad

j

ective) =

Mexican

(

noun

)

Peri

p

hrasis

walk

ĺ

i

s walkin

g

loo

k

+ u

p

ĺ

l

ook u

p

H

ead marking

unde

r

stand

ĺ

unde

r

stood

pass b

y

ĺ

passerb

y

B

lockin

g

went

b

l

oc

k

s

*

goed judg

e

(

n.

)

blocks

*

judger

*

62

G

REGORY

T

.

ST

U

MP

noncollective expressions of various sorts: it may combine with a mass noun to

produce a count noun, and it may join with a count noun or an adjective to produce a

semantically related noun; cf. Table 7. Whatever the properties of the base with which

i

t

j

oins, -

enn

alwa

y

s produces a feminine noun.

C

ollective nou

n

Singulative nou

n

‘

wo

rm

s

’

b

uzhug buzhugenn

‘midges’

c

’

hwibu c

’

hwibuenn

‘glasses’ gwer gwerenn

‘tr

ees’

gwe

z

gwe

z

enn

‘cabbages

’

kol kolenn

‘fli

es’

kelien kelienenn

(and

kelién,

d

by haplology)

‘

w

aln

u

t

s

’

k

r

aon k

r

aonenn

‘mi

ce

’

l

ogod logodenn

‘ant

s

’

melien melienenn

(and

melién,

d

by haplology

)

‘slu

g

s

’

melved melvedenn

‘nit

s’

ne

z

ne

z

enn

‘pears

’

per perenn

‘

s

tra

wbe

rri

es

’

sivi sivienn

Ta

b

l

e

6

B

reton collective nouns and their sin

g

ulatives in -enn (Stump 1990b

)

B

a

se

D

e

ri

v

ati

ve

Ma

ss

n

oun

C

ount nou

n

doua

r ‘earth,

g

round’

doua

r

enn

‘

p

lot; terrier’

geo

t

‘grass

’

g

eotenn ‘blade of grass’

kaf

e

‘

coffee

’ kafeenn ‘

co

ff

ee be

an’

kolo

‘

s

tra

w

’

koloenn

‘wisp of straw’

C

ount nou

n

Re

lat

ed

n

oun

boute

z ‘

s

h

oe’

bote

z

enn

‘a ki

c

k’

c

’

hoant

‘a

w

ant’

c

’

hoantenn

‘

b

irthmark’

ene

z ‘i

s

lan

d

’

ene

z

enn

‘i

s

lan

d

’

l

a

g

ad ‘e

y

e’

l

a

g

adenn ‘e

y

elet

’

lod

‘

p

art’

lodenn

‘

p

art

’

lost

‘tail’

lostenn

‘

s

kirt’

pre

z

eg

‘preachin

g

’

pre

z

egenn

‘

se

rm

o

n’

A

d

j

ective Related

noun

bas

‘

s

hall

ow

’

basenn

‘s

h

o

al’

koant

‘pretty’

koantenn

‘

pretty girl’

lous

‘dirt

y

’

lousenn

‘

slovenl

y

woman’

uhel

‘high’

uhelenn

‘

high ground’

Ta

b

l

e7

B

reton derivatives in -enn havin

g

noncollective bases (Stump 1990b)

W

OR

D

-

F

ORMATION AND INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

63

I

s

th

esu

ffix -

enn

inflectional or derivational? Given that it converts adjectives to

n

ouns and that it always determines the gender of the form to which it gives rise, -

enn

i

s clearl

y

derivational b

y

criterion (A). Moreover, althou

g

h -

enn

j

oins ver

y

freel

y

with

c

ollective nouns, it is much more s

p

oradic in its combinations with mass nouns, count

n

ouns, and ad

j

ectives; thus, -

enn

can be plausibly regarded as derivational by criterio

n

(B). Similarl

y

, althou

g

h the semantic relation between collectives and thei

r

s

ingulatives is quite regular, the semantic relations between nominal derivatives i

n

-

enn

and their bases are much less regular in instances such as those in Table 7; thus,

c

riterion

(

C

)

also favors the conclusion that -

enn

is a mark of derivation. And

g

ive

n

th

a

t -

enn

may precede a derivational suffix (as in forms such as

gwerennad

‘glassful’

d

[

ĸ

gwerenn

,

singulative of

gwer

‘glasses’]), criterion (E) might be claimed to add

r

f

u

rth

e

r f

o

r

ce

t

o

thi

sco

n

c

l

us

i

o

n

.

This conclusion is, however, apparently disconfirmed by criterion (D), since the

c

hoice between a singulative noun and its collective counterpart is determined by

precisely the same syntactic contexts as the choice between an ordinary singula

r

n

oun and its plural counterpart; for instance, the syntactic contexts that determine

t

he choice between the singular noun po

tr

‘boy’ (lenited form

r

bot

r) and its plural

c

ounterpart

potred

‘boys’ in Table 8 likewise de

d

te

rmin

e

th

ec

h

o

i

ce be

t

wee

n th

e

s

ingulative noun

sivienn

‘strawberry’ (lenited for

m

zivienn

)

and its collective

c

ounterpart

sivi

‘strawberries’. Thus, by criterion (D), -

enn

must seemingly be seen

a

s

an infl

ec

ti

o

nal

su

ffix

.

POT

R

‘boy’

R

SIVI ‘

s

tra

wbe

rri

es

’

Sin

g

ular: pot

r

Singulative:

r

sivienn

Singula

r

co

nt

e

xt

s

u

r

p

otr

bennak

‘a certain boy’

u

r

zivienn

bennak

‘a certain strawberry’

meur

a

bot

r

‘

man

y

a bo

y

’

meur

a

zivienn

‘man

y

a strawberr

y

’

Pl

u

ral

:

potred

Collective:

d

sivi

Pl

u

ral

co

nt

e

xt

s

un

nebeud

potred

‘some bo

y

s’

un

nebeud

sivi

‘

so

m

es

tra

wbe

rri

es

’

kal

z

p

otred

‘

a lot of boys’

kal

z

sivi

‘a l

o

t

o

f

s

tra

wbe

rri

es

’

Ta

b

l

e

8 Forms of POT

R

‘boy’ and

SIVI

‘strawberries’

I

i

n singular and plural contexts

This contradiction amon

g

criteria is, however, onl

y

apparent. Distinct stems

o

ften participate in the definition of distinct parts of a lexeme’s paradi

g

m.

Accordingly, one would, in the absence of

c

ontrary evidence, expect that the stems

participating in the definition of a lexeme’s paradigm might in some cases include

t

he stem of a derivative of that lexeme. Thus, in the paradigm of a Breton collective

nou

n

suc

h a

s

SIVI

‘

strawberries’, the plural cell is apparently associated with the

64

G

REGORY

T

.

ST

U

MP

c

ollective stem

(

sivi

), while the singular cell is instead associated with the stem of

t

he singulative derivative (

SIVIENN

)

. The fact that -

enn

i

s

a

de

ri

v

ati

o

nal

su

ffix in n

o

way excludes the participation of

sivienn-

in th

ede

finiti

o

n

o

f SIVI

’s

infl

ec

ti

o

nal

paradi

g

m.

J

ust as a derivational process ma

y

(as in Table 8) have a role in expressin

g

a

l

exeme’s inflection, a lexeme’s inflection ma

y

likewise have a role in expressin

g

its

status as a derivative. Quite frequently in language, the sole morphological

e

xpression of a lexeme’s derivation is the way in which it inflects. Inflectionally

e

x

p

ressed derivation of this sort can ari

s

e

in more than one way. On one hand, a

l

exeme’s status as a derivative may be morphologically expressed purely by its

i

nflection for a particular set of morphosyntactic properties. Thus, Kikuyu has a

productive process for the derivation of diminutive nouns whose morpholo

g

ical

e

ffect is to shift nouns into

g

ender 13/12; the sole si

g

n of diminutivization in the

derivatives arisin

g

b

y

means of this process

i

s the fact that the

y

inflect as members

o

f gender 13/12

.

8

For instance, the Kikuyu noun

ARA

‘finger’ (stem -

a

r

a

) ordinarily

i

nflects as a member of gender 7/10, exhibiting the class 7 prefix

k

ƭ

- in the singular

ƭ

ƭ

(

k

ƭ

a

r

a

ƭ

ƭ

) and the class 10 prefix

ci

-

in the plural (

cia

r

a

)

; the diminutive derivative of

A

R

A

s

till ha

s

-

ara

as its stem, differing from its base only in that it takes the class 13

prefix

ka

-

in the singular (

kaa

r

a

) and the class 12 prefix

t

NJ

-

i

n the plural (

t

NJ

ara

).

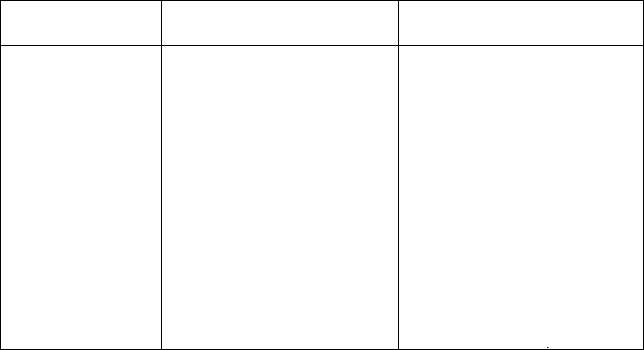

Infl

ec

ti

on

c

la

ss

Infl

ec

ti

o

n-

c

la

ss

a

ffi

x

Sample present-s

y

stem

s

t

em

Th

e

mati

c

I -

a bhava

-

‘

be’

c

on

j

u

g

ations

IV

-

V

ya

-

‘pla

y

’

VI

-

I

a tuda

-

‘thr

us

t’

X

-

X

aya ‘

c

a

use

t

o

hat

e

’

A

th

e

mati

c

I

I

(none)

I

‘hat

e

’

c

on

j

u

g

ations II

I

reduplicative prefix

I

j

uh

o

-

‘

s

a

c

rifi

ce’

V

-

V

no

suno

-

‘

p

ress out’

VII

infix -

I

na

-

runadh

-

‘

obs

tr

uc

t’

V

III -

o

tano

-

‘

s

tr

e

t

c

h

’

IX

‘buy’

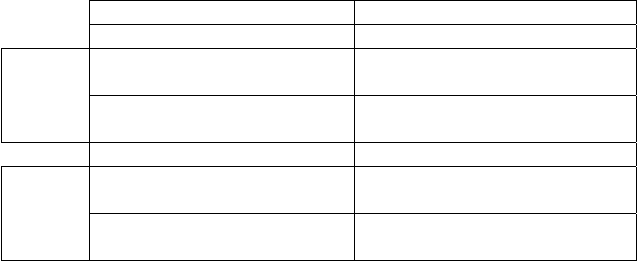

Table 9

T

he ten traditional present-system conjugation classes in Sanskri

t

A lexeme’s derivative status ma

y

likewise be revealed purel

y

b

y

the sort o

f

i

nflection-class marking which it exhibits. Sanskrit, for example, has a productive

process for the derivation of causative verbs; in morphological terms, however, this

process simply amounts to shifting a verb into the tenth conjugation

.

9

For instance

,

t

h

eve

r

b

DVI ‘hate’, a member of the second conjugation, gives rise to a causative

8

F

acts of this sort are sometimes cited in support of the claim that Bantu nou

n

-

c

la

ss

infl

ec

ti

o

n

s

ha

ve bo

th

i

nfl

ec

ti

o

nal an

dde

ri

v

ati

o

nal functions; see, for example, Mufwene (1980)

.

9

It i

s

th

e

r

e

f

o

r

eso

m

e

tim

es

a

ssu

m

ed

that th

e

t

e

nth

c

o

n

j

u

g

ation is actuall

y

a derivational class rather than

an inflection class; see Stum

p(

2004

)

fo

r

arguments against this conclusion.

d

Ư

vya

ƯƯ

-

dves

́a

y

a

-

dves

́

-

s

-

n

Ɨ

k

r

Ư

n

Ư

Ư

́

Ɨ

-

S