Spier C.A., Barros de Oliveira S.-M., Rosi?re C.A., Ardisson J.D. Mineralogy and trace-element geochemistry of the high-grade iron ores of the ?guas Claras Mine and comparison with the Cap?o Xavier and Tamandu? iron ore deposits, Quadril?tero Ferr?fe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

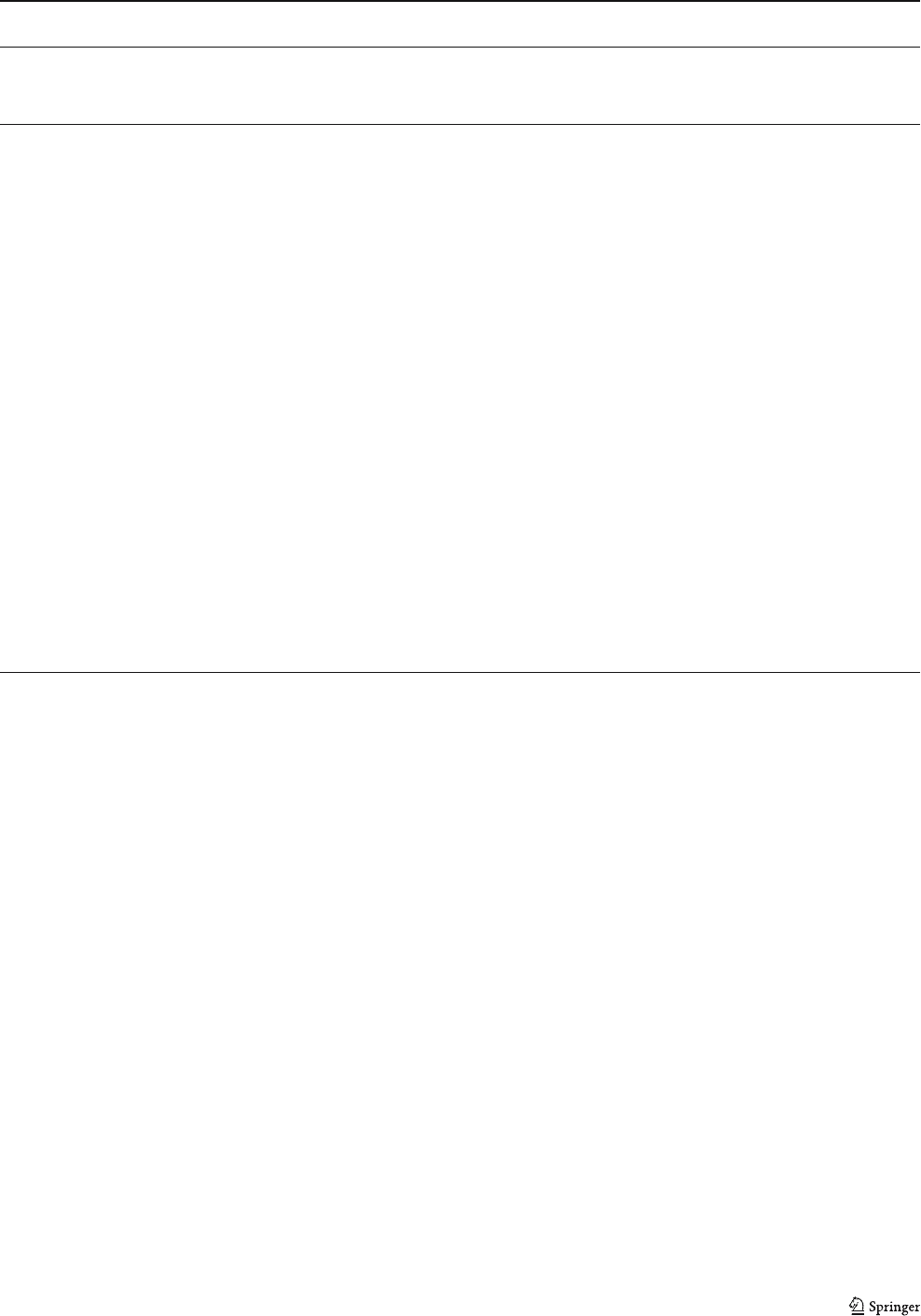

oxides (Figs. 8a–d and 9a). The soft ore is highly porous,

with intergranular porosity estimated in thin sections at 35–

45%. Hematite is the major iron oxide in both bands,

occurring as martite, anhedra l to granular/tabular hematite

and, locally, specularite. Magnet ite is locally observed as

relics within martite and granular hematite crystals, espe-

cially within thicker massive bands. Ferrihydrite (identified

by Mössbauer analyses; see text below) is more frequent

within the porous bands. Gangue minerals are rare,

increasing in amount in samp les obtained close to contacts

with both the protore and the phyllite. They are also more

frequent within the porous bands and consist of apatite,

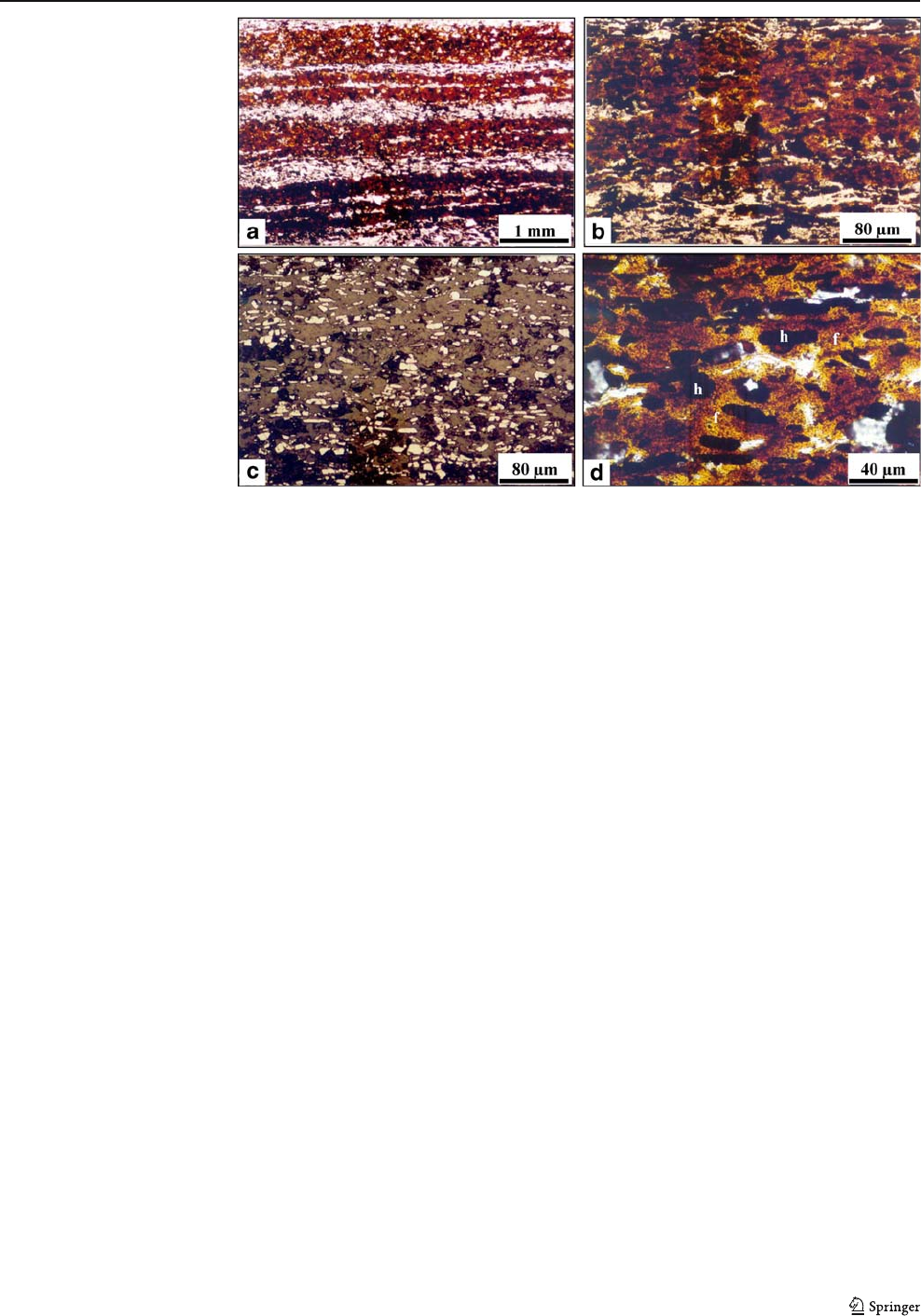

talc, chlorite, and Mn oxides (Fig. 10a–f). Apatite is more

frequent in samples from the lower levels of the mine where

the pinnacles of dolomitic itabirite occur.

Even massive bands of iron oxide are porous, but they

have less than 30% of pore space, and individual pores are

isolated in massive hematite. Generally massive bands are

broken and disrupted, whereas porous bands show individ-

ual aggregates of hematite between pores (Fig. 8c,e).

The massive bands of the soft ore generally show a

granoblastic fabric and consist of fine granular and tabular

hematite (5–20 μm), forming a dense package of hematite

(Fig. 8g). The porous bands have variable porosity, visually

estimated at 30–60%. They consist of aggregates ranging

from 50 μm to 10 mm of granular and tabular hematite

crystals (up to 60%) and/or of individual crystals of tabular

hematite ranging from 10 to 30 μm (Fig. 8e,f ). Tabular and

granular hematite overgrows coarser martite crystals

(∼50 μm). Disaggregation of these coarse martite crystals

releases fine tabular hematite crystals (Fig. 8h). Hematite

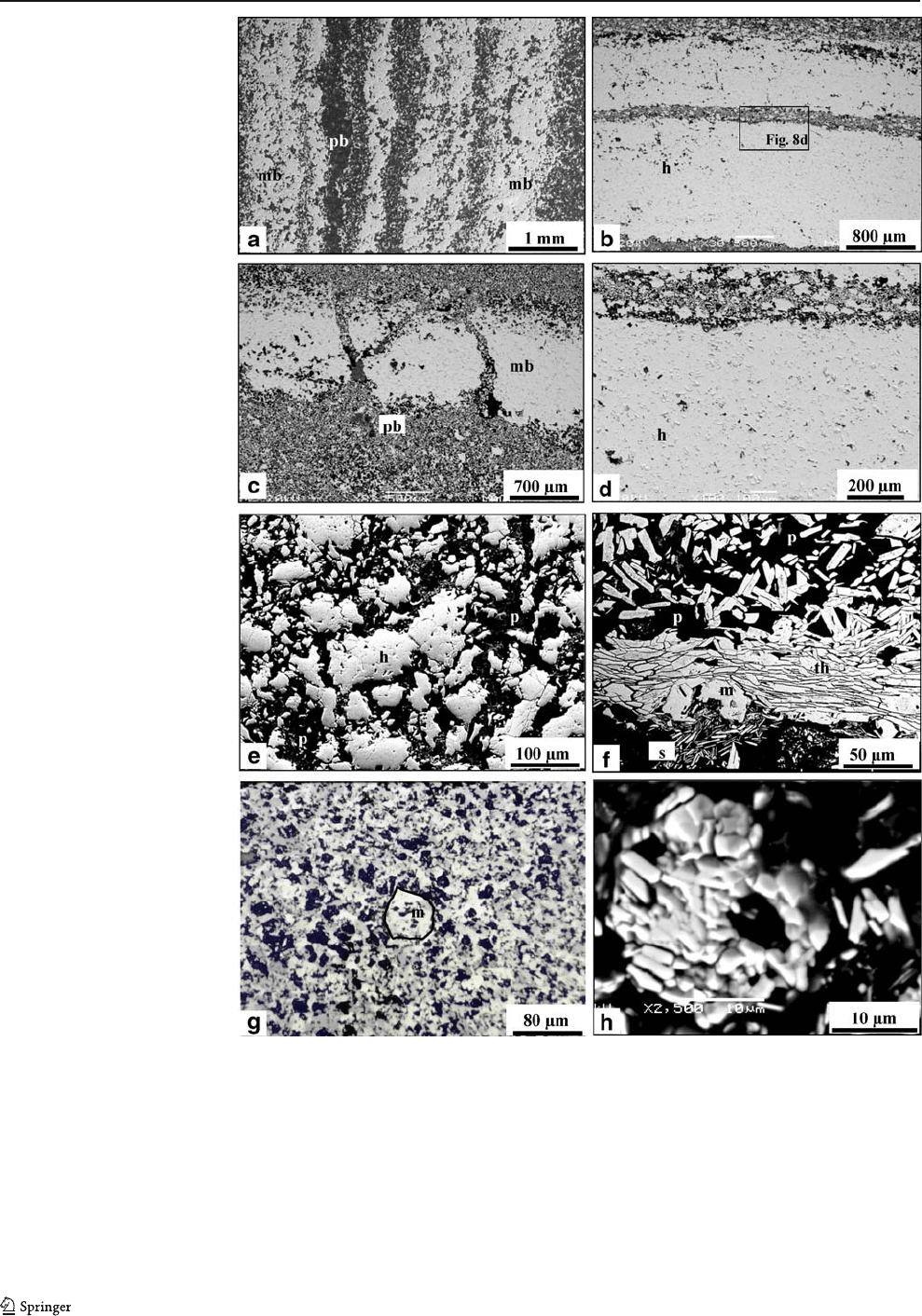

crystals are surro unded by a brownish residue of poorly

crystalline ferrihydrite (Fig. 9a–d).

The SEM observations of the <0.15-m m size fraction of

some samples (Electronic supplementary material

Appendix A) of the soft ore detected a limited amount of

small particles of Mn oxides besides hematite (Fig. 10d).

The TEM analyses also confirmed the presence of these Mn

oxides within the porous bands. They occur as small

particles (∼100 nm) mixed with the iron oxides.

In samples collected from the contact zone with the

protore, remnants of dolomite intergrown with hematite and

gangue are observed. Apatite is well preserved in this zone,

forming thin laminae parallel to the bandin g or occurring as

Table 2 Mössbauer hyperfine parameters of iron ore and dolomitic itabirite samples

Sample

code

Sample

description

Temperature

(K)

Subspectrum Isomer shift

(±0.05)

(mm·s

−1

)

Quadrupole

splitting (±0.05)

(mm·s

−1

)

Hyperfine

field (±0.6)

(T)

Line Width

(±0.5)

(mm·s

−1

)

Relative

abundance

(%)

Mac67 HO 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.16 51.9 0.34 100

Mac68 HO 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.15 51.9 0.34 100

Mac97 HO 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.16 51.9 0.34 100

Mac97 HO 50 Hematite 0.48 0.38 55.8 0.37 100

Mac105 HO 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.15 51.9 0.35 100

Mac126A SO-massive 300 Hematite 0.36 −0.16 51.9 0.34 100

Mac127A SO-massive 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.16 51.9 0.34 100

50 Hematite 0.48 0.37 54.9 0.37 100

Mac128A SO-massive 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.17 51.9 0.34 100

Mac129A SO-massive 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.15 51.9 0.35 100

Mac126B SO-porous 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.13 51.9 0.34 98

Ferrihydrite 0.34 0.68 – 2

Mac127B SO-porous 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.13 51.9 0.34 98

Ferrihydrite 0.34 0.68 – 2

50 Hematite 0.48 0.32 54.9 0.39 97

Ferrihydrite 0.42 0.76 – 0.48 3

Mac128B SO-porous 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.13 51.9 0.34 98

Ferrihydrite 0.34 0.68 – 2

Mac129B SO-porous 300 Hematite 0.36 −0.13 51.9 0.34 98

Ferrihydrite 0.35 0.68 – 2

Mac96 Dol. itabirite 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.14 51.9 0.34 98

Siderite 1.20 1.60 – 2

Mac100 Dol. itabirite 300 Hematite 0.37 −0.13 51.9 0.34 90

Siderite 1.20 1.55 – 10

50 Hematite 0.48 0.39 54.8 0.34 90

Siderite 1.37 2.03 – 0.51 10

HO Hard ore, SO-massive massive band of the soft ore, SO-porous porous band of the soft ore, Dol. itabirite dolomitic itabirite

Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254 239

isolated euhedral crystals (Fig. 10a–c). Talc and chlorite

occur as isolated crystals or forming millimetric aggregates

(Fig. 10e,f).

The 300 K Mössbauer spectra of the soft ore samples fit

perfectly with hematite (Table 2). MS also revealed the

presence of the Morin transition (a transition from an

antiferromagnetic to a weakly ferromagnetic state, at about

265 K). This transition is very sensitive to microcrystalline

effects, lattice imperfections, and impurities. Its record in

the studied samples also indicates a very pure composition

of hematite and crystallites larger than 20 nm, which was

also indicated by the unit cell parameters obtained for the

hematite in the sample MAC127A (Table 3), which are

similar to those of the reference cell of hematite.

A r epresentative Mössbauer spectrum at 300 and at

50 K of the porous bands from sample MAC127B is

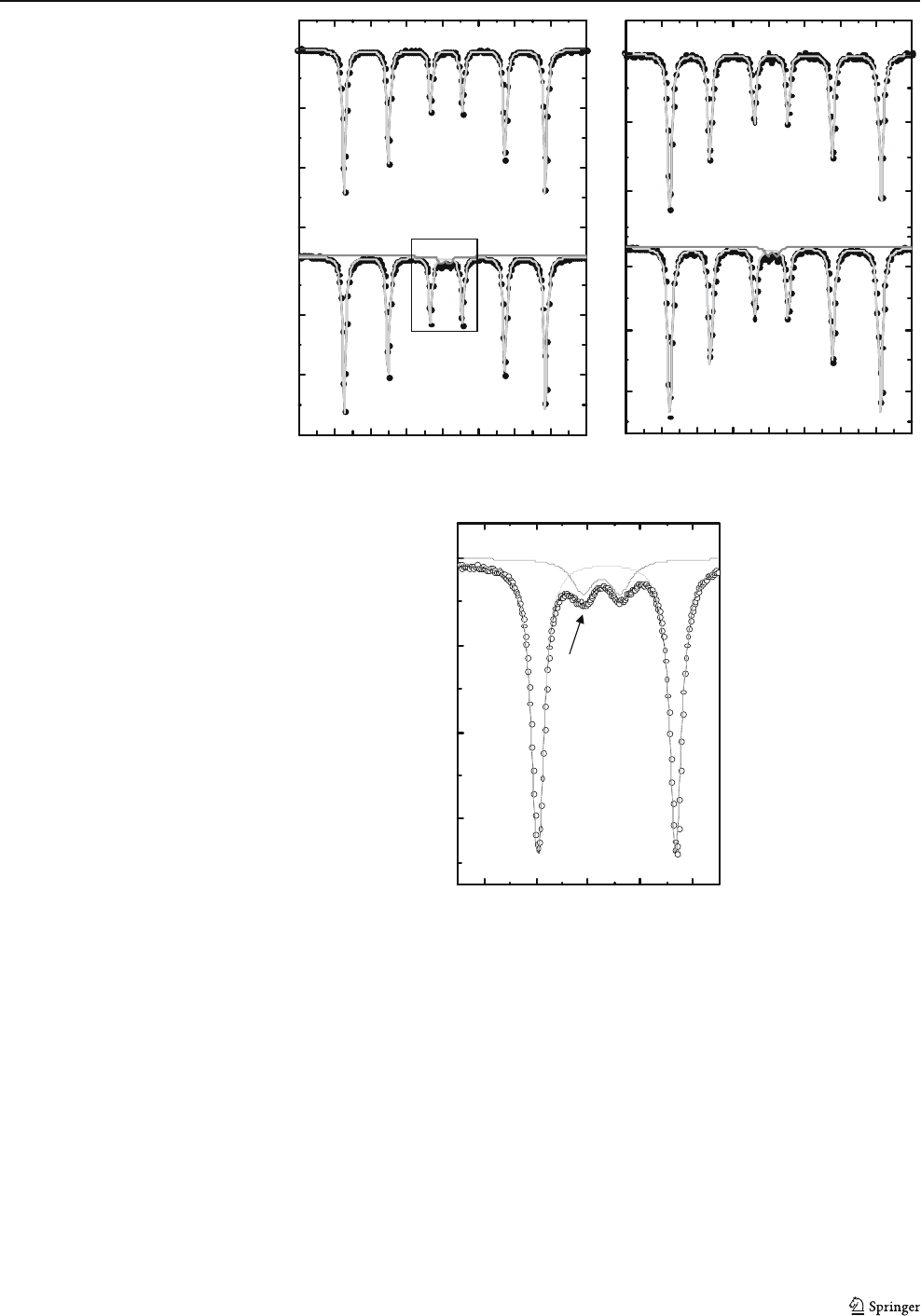

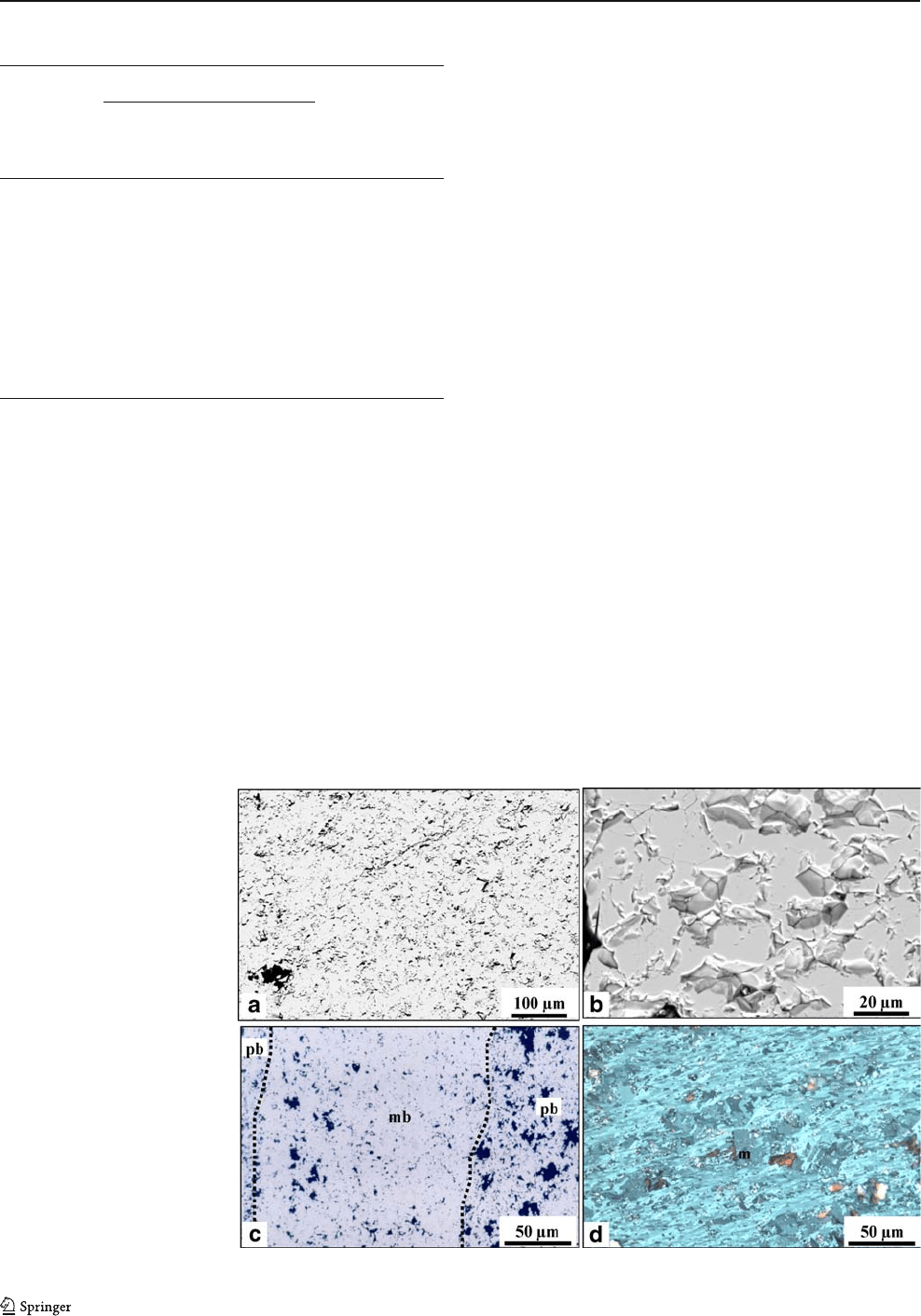

Fig. 8 SEM backscattered

images and photomicrographs

of the soft ore. a, b and c

Typical image of soft ore show-

ing massive (mb, white) and

porous (pb, black) bands locally

broken and disrupted (c). Note

the preservation of microband-

ing of the protore. d Detail of a

massive band showing the dense

packing of hematite (h), SEM

image. e Detail of a porous band

showing aggregates and indi-

vidual crystals of hematite (h)

between pores (black). f Coarse

crystals of tabular hematite (th)

in the massive and porous

bands, surrounding a porphyro-

blast of martite (m) in the for-

mer. Note the small crystals of

specularite (s) in the lower part

of the picture. g Massive band

showing granoblastic fabric of

granular/tabular hematite grow-

ing over martite (m), reflected

light, PPL. h Small crystals of

tabular hematite developed

within ex-martite grain, SEM

image

240 Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254

depicted in Fig. 11c,d. Besides the major sextet that f itted

perfectly with hematite, an ill-defined doublet super-

imposed to the hematite sextet is present in all spectra of

the studied samples (Fig. 11e). This doublet can be

ascribed to the amorphous limonitic brownish material

which is the residue of the dissolution of dolomite. The

isomer shift (0.34–0.35 mm/s) and the quadrupole split-

ting (0.68 mm/s) at 300 K of these samples match well

with those of ferrihydrite (Cornell and Schwertmann 1996,

p 149). In the MS at 50 K, the doublet is still present, with

an isomer shift of 0.42 mm/s and a quadrupole splitting of

0.76 mm/s. These values are compatible with those found

by Childs and Baker-Sherman (1984) for synthetic

ferrihydrite at 77 K. The absence of a sextet at 50 K

indicates the poor cryst allinity of ferrihydrite, given th at

magnetic ordering is strongly dependent on crystallinity

(Cornell and Schwertmann 1996). The low crystallinit y of

ferrihydrite, on the other hand, explains its absence from

the XRD patterns. Mössbauer spectroscopy confirms,

therefore, that the brownish mate ri al obser v e d by op ti c al

petrography in the residue of the dolomite dissolution is

ferrihydrite. Based on the values of the relative subspect ral

areas, t he abundances of hematite and ferrihydrite were

estimated. It is seen from Table 2 that ferrihydrite is a

subordinate component in the soft ore.

Geochemistry

Analytical results for the 48 samples analyzed for major,

trace, and REE of the soft and hard ores are presented in

Electronic supplementary material Appendices B and C.

Average compositions and standard deviations of popula-

tions for the soft and hard iron ores are given in Tables 4

and 5. Statistics for variables below or very close to the

detection limit were not calculated. When the results of just

a few samples were below this limit, statistics were

calculated using half the detection limit. This procedure

was chosen to establish a distinction for those values, which

were slightly above the detection limit. The following

variables (with their respective detection limit) presented

analytical results below or very close to the detection limit:

Na

2

O (0.01%), K

2

O (0.01%), Sc (3 ppm), Be (3 ppm), Zn

(30 ppm), Ga (1 ppm), Rb (1 ppm), Nb (0.2 ppm), Mo

(2 ppm), In (0.1 ppm), Sn (1 ppm), Cs (0.1 ppm), Hf

(0.1 ppm), Tl (0.1 ppm), Pb (5 ppm), Bi (0.1 ppm), Au

(2 ppb), Br (0.5 ppm), Ir (5 ppm), and Se (3 ppm).

The soft iron ore consists almost entirely of Fe

2

O

3

(average 95.6 wt%), with FeO representing less than 0.5%

(average 0.1 wt%). The average values of major elements in

the massive and porous band of the soft ore were analyzed

separately to confirm the results of petrological analyses

and show that impurities are concentrated within the porous

bands (Table 4). These impurities consist almost entirely of

SiO

2

(average 1.7 wt%), MnO (average 1.7 wt%), and

Al

2

O

3

(average 0.8 wt%) and are mineralogically expressed

by chlorite, talc, and Mn oxides.

Trace element concentrations encountered in the soft ore

are very low (Table 4). Most elements show concentrations

of less than 10 ppm, except for Ba (33 ppm), V (60 ppm),

Cr (79 ppm), Y (19 ppm), Ni (24 ppm), Cu (79 ppm), and

∑REE (23 ppm). When compared to the average compo-

sition of dolomitic itabirite (Table 4), the soft ore is

Fig. 9 Photomicrographs of the

soft ore. a Microbanding of

massive and porous bands,

transmitted light. b, c Detail of a

porous band, transmitted light

(b), reflected light, PPL (c). d

Detail of the previous picture (b)

showing ferrihydrite (f)

surrounding aggregates and

individual crystals

of hematite

Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254 241

enriched in all trace elements, except for Sr and Nb. Trace

elements are concentrated in the porous bands of the soft

ore (Table 4). Only Ge, Cr, Sb, V, and Ni have similar

values in the porous and massive bands. Some elements,

such as Ba (10x), Y (10x), REE (9x), and Th (7x), are

highly enriched in the porous bands if compared to the

massive bands.

The average REE composition of the soft ore is presented

in Table 5.TheREEY

PAAS

patterns are shown in Fig. 12a,b.

These patterns show similar trends, characterized by a

pronounced depletion in the light REE relative to heavy

REE (average La/Yb

PAAS

=0.2). This depletion occurs either

in the LREE group (average La/Sm

PAAS

=0.5)aswellasin

the HREE group (average Dy/Yb

PAAS

=0.8). Most samples

display strong positive anomalies of Eu

PAAS

(Eu/Eu*=1.7)

and Y

PAAS

(Y/Y*=2.1), as well as negative anomalies of

Ce

PAAS

ranging from 0.7 to 1.0.

Mass balance calculation

The mass balance of the transition of dolomitic itabirite to

soft ore was calculated in accordance to the works of

Fig. 10 SE M b ackscattered

images of gangue minerals in

the iron ore. a Microbanding of

apatite-rich laminae (a)

between massive bands (mb)of

hematite. b Detail of the apatite-

rich laminae. c Porous band of

the soft ore showing apatite (a)

and aggregates of hematite (h)

between pores (p). d Detail of

the size fraction <0.15 mm of

the soft ore showing small crys-

tals of Mn oxides on the surface

of hematite aggregates, SEM

image, secondary electrons. e

Porous band of the soft ore

showing aggregates of talc (t)

and hematite (h) between pores.

f Detail of the previous

picture (e)

Table 3 Unit cell parameters of hematite in the iron ores of the Águas

Claras Mine

Sample Ore type aÅ cÅ

MAC67 Hard ore 5.0347(1) 13.7474(2)

MAC97 Hard ore 5.0355(1) 13.7485(2)

MAC127A Massive band

of the soft ore

5.0338(1) 13.7470(2)

MAC127B Porous band

of the soft ore

5.0339(1) 13.7468(2)

Reference cell

of hematite

5.0340 13.7520

Data for the refer ence cel l of hema tite a re from Cornell and

Schwertmann (1996, p 5).

242 Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254

Brimhall et al. (1991), Brimhall and Dietrich (1987 ), and

Chadwick et al. (1990) and is based on the assumption that

the transformation of a protolith into altered material takes

place together with conservation of some highly immobile

elements (e.g., Ti, Zr, etc.) and, at later stages, the collapse

of the original structures, generating a volume decrease.

The following equations were utilized for calculating

volume variation and mass balance:

"

i;w

¼ 100 ρ

p

C

i;p

.

ρ

w

C

i;w

hi

1

no

ð1Þ

τ

j;w

¼ 100 C

j;w

C

i;p

C

j;p

C

i;w

1

ð2Þ

where,

"

i,w

volume change during weathering (%) using

immobile element I

τ

j,w

gain (+) or loss (−) of the mobile element j during

weathering (%)

i subscript of the immobile element;

j subscript of the mobile element

C

i,p

chemical concentration of i in the dolomitic itabirite

(%=g/100 g)

-12 -9 -6 -3 0 3 6 9 12

0,8 5

0,9 0

0,9 5

1,0 0

MAC-127B

300K

Velocity (mm/s)

0,8 5

0,9 0

0,9 5

1,0 0

MAC-127A

300K

Relative Transmission (%)

-12 -9 -6 -3 0 3 6 9 12

0,93

0,96

0,99

MAC-127B

50 K

Velocity (mm/s)

0,92

0,96

1,00

MAC-127A

50K

b

Fig. 11E

a

d

c

-2 -1 0 1 2

0,94

0,96

0,98

1,00

Relative transmission

Velocit

y

(

mm/s

)

Ferrihydrite

e

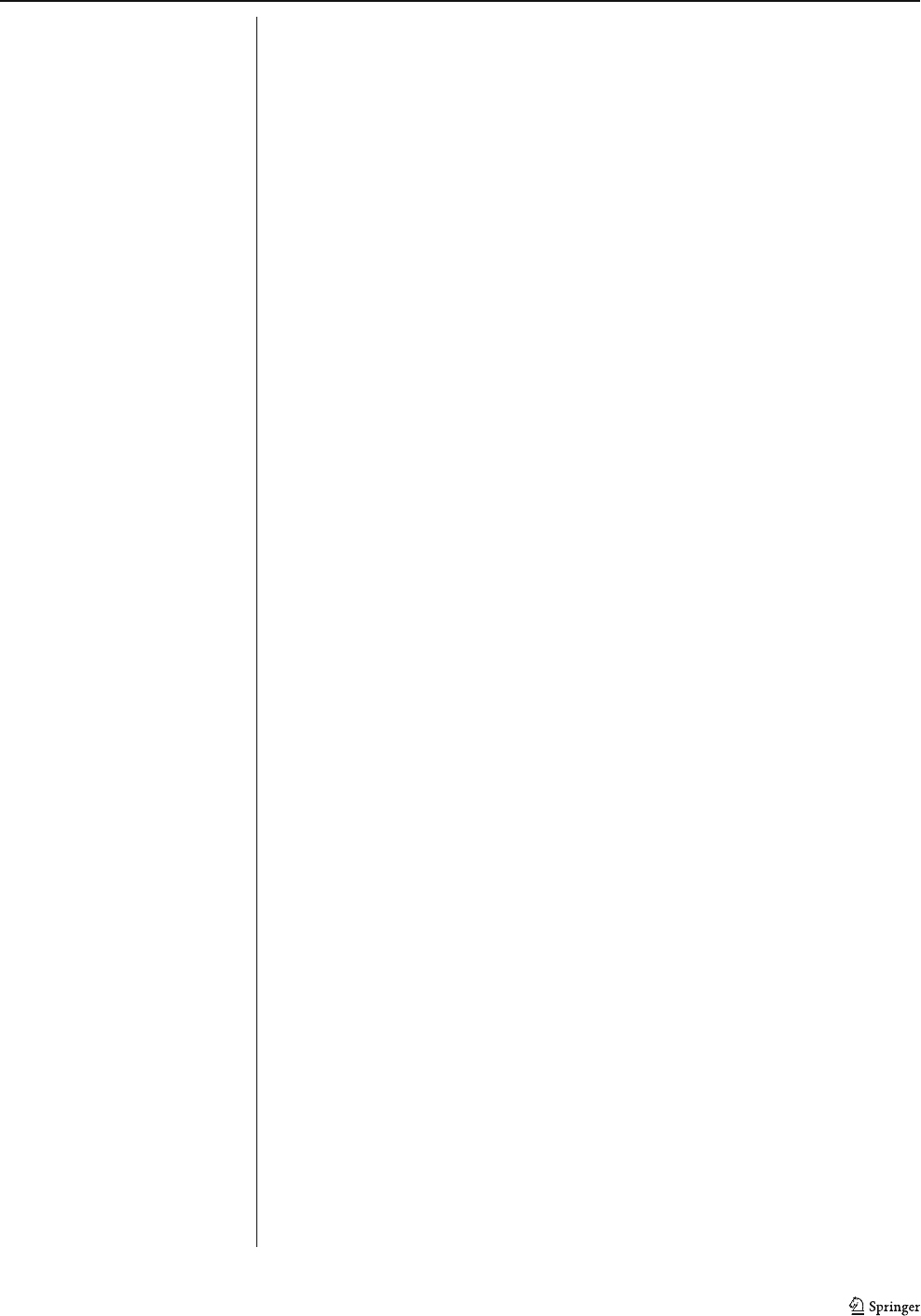

Fig. 11 Mössbauer spectra at

300 and at 50 K of the massive

(a, b) and porous (c, d) bands of

the sample MAC127 (soft ore).

e Detail of the central part of the

spectra of the porous band at

300 K showing the doublet of

ferrihydrite

Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254 243

Table 4 Average major and trace element composition

Hard ore Soft ore Dolomitic

Itabirite

(n=11)

Soft ore Dolomitic itabirite

Massive band (n=6) Porous band (n=8) Iron-rich

band (n=6)

Dolomite-rich

band (n=6)

Wt% Avg Std Min Max n Avg Std Min Max n Avg Std Min Max Avg Std Min Max Avg Avg

SiO

2

0.66 0.33 0.24 1.32 12 1.06 0.63 0.18 3.57 62 1.01 0.35 0.13 0.15 0.51 1.69 1.48 0.38 4.74 0.91 0.73

Al

2

O

3

0.24 0.23 0.02 0.91 12 0.46 0.44 0.08 2.10 62 0.32 0.08 0.05 0.03 0.16 0.84 1.13 0.14 3.25 0.28 0.33

Fe

2

O

3

97.66 1.16 95.11 99.13 10 95.65 2.29 87.66 98.79 62 48.90 98.24 0.85 96.84 99.15 92.80 3.84 86.96 97.07 77.88 10.93

Fe

TOT

97.93 1.77 94.44 99.54 12 95.74 2.31 87.72 98.90 62 49.64 98.58 0.53 97.90 99.27 92.98 3.76 87.22 97.07 78.23 11.74

FeO 0.82 0.80 0.22 2.70 10 0.08 0.07 0.05 0.50 62 0.66 0.36 0.55 0.11 1.35 0.19 0.10 0.10 0.37 0.32 0.73

MnO 0.025 0.025 0.005 0.093 12 0.818 0.379 0.221 2.139 62 0.28 0.10 0.10 0.02 0.29 1.69 0.63 0.77 2.55 0.12 0.50

MgO 0.22 0.35 <0.03 1.20 12 0.36 0.32 0.03 2.04 62 10.33 0.08 0.03 0.02 0.11 0.54 0.73 0.07 2.29 4.11 18.50

CaO 0.33 0.42 0.02 1.41 12 0.19 0.22 <0.03 1.13 62 14.36 0.10 0.14 0.03 0.38 0.12 0.11 <0.03 0.31 5.45 26.19

Na

2

O <0.01 12 <0.01 36 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 0.05

K

2

O 0.044 0.041 <0.01 0.140 12 <0.01 36 0.03 <0.01 <0.01 0.02 0.06

TiO

2

0.018 0.009 0.006 0.033 12 0.031 0.035 0.005 0.156 62 0.021 0.006 0.003 <0.001 0.010 0.054 0.076 0.011 0.223 <0.001 <0.001

P

2

O

5

0.13 0.07 0.03 0.22 12 0.18 0.27 <0.03 1.58 62 0.12 0.06 0.10 <0.03 0.27 0.10 0.07 0.03 0.25 0.12 0.06

LOI 0.52 0.41 0.13 1.39 12 0.85 0.44 0.29 2.31 62 23.60 0.32 0.10 0.19 0.45 1.86 0.81 0.78 2.97 9.91 40.98

Ppm

a

Ba 13.1 10.6 <3.0 37.2 12 32.7 35.1 6.7 211.0 62 12.9 11.5 9.8 <3.0 29.4 116.2 127.2 20.7 405.2 11.17 20.67

Sr 6.2 3.2 <2.0 9.3 10 18.2 10.9 4.0 35.5 24 29.8 3.8 4.5 <2.0 12.4 17.4 12.9 2.3 42.8 12.83 46.17

Y 5.0 1.5 2.2 7.6 10 18.8 9.5 5.5 33.7 24 7.7 3.1 1.6 2.0 6.1 32.6 13.6 13.9 56.0 4.67 9.50

Sc <3.0 10 <3.0 24 <3.0 <3.0 <3.0 <3.0 <3.0

Zr 5.8 3.8 2.4 15.1 10 13.6 9.9 3.5 40.1 24 14.0 3.2 1.1 2.2 4.8 9.4 11.9 2.3 38.6 14.67 8.00

Be <3.0 10 <3.0 24 <3.0 <3.0 <3.0 <3.0 <3.0

V 35.6 35.6 10.0 132.0 10 59.9 36.0 9.1 138.4 62 25.6 27.2 25.1 9.2 77.0 44.5 21.0 23.0 75.0 36.33 10.25

Ni <20.0 10 23.9 21.1 <20.0 96.0 62 10.0 <20.0 30.5 18.6 <20.0 63.6 15.13 7.31

Cu 10.0 6.0 <5.0 22.0 10 10.2 7.3 <5.0 45.3 62 7.0 <5.0 31.9 42.0 <5.0 115.3 0.50 5.19

Zn <30.0 10 <30.0 62 13.5 <30.0 101.2 128.1 <30.0 407.1 12.95 7.38

Ga <1.0 10 <1.0 24 <1.0 <1.0 2.1 1.7 <1.0 5.9 0.79 <1.0

Ge 4.3 1.1 2.8 6.0 10 3.0 1.1 0.7 5.0 24 1.8 3.8 0.8 3.1 5.3 4.0 1.3 2.1 6.0 3.6 <0.5

Rb <1.0 10 <1.0 24 <1.0 <1.0 <1.0 1.24 <1.0

Nb 0.4 0.4 <0.2 1.0 10 <0.2 24 0.9 0.3 0.3 <0.2 0.5 0.8 0.80 <0.2 2.4 0.36 0.88

Mo <2.0 10 <2.0 24 <2.0 <2.0 <2.0 1.49 <2.0

Ag <0.5 10 0.3 0.4 <0.5 1.3 24 <0.5 <0.5 <0.5 0.41 <0.3

In <0.1 10 <0.1 24 <0.1 <0.1 <0.1 0.05 <0.1

Sn <1.0 10 <1.0 24 <1.0 <1.0 <1.0 0.64 <1.0

Cs <0.1 10 <0.1 24 <0.1 <0.1 <0.1 0.21 <0.1

ΣREE 7.0 1.9 3.2 10.0 10 22.7 10.1 9.3 46.0 24 13.9 5.0 1.5 3.6 7.6 42.9 31.8 14.4 116.9 9.63 18.76

Hf <0.1 10 <0.1 24 0.1 <0.1 <0.1 <0.1 <0.1

Tl <0.1 10 <0.1 24 <0.1 <0.1 <0.1 <0.1 <0.1

Pb <5.0 10 <5.0 24 5.1 <5.0 13.7 23.2 2.5 70.5 1.5 7.01

244 Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254

C

i,w

chemical concentration of i in the soft ore

(%=g/100 g)

C

j,p

chemical concentration of j in the dolomitic itabirite

(%=g/100 g)

C

j,w

chemical concentration of j in the soft ore

(%=g/100 g)

ρ

p

dry bulk density of the dolomitic itabirite (g/cm

3

);

ρ

w

dry bulk density of the soft ore (g/cm

3

).

A positive volume ("

i,w

) variation represents dilation,

and a negative one, collapse. The collapse is indicated by

Eq. 1 when an increase of the concentration of the

immobile element (C

i,w

) in the soft ore, caused by loss of

the mobile components of the dolomitic itabirite, is not

fully compensated by an inversely proportional decrease of

the bulk density (ρ

w

) due to a porosity increase so that the

product of C

i,w

by ρ

w

remains constant.

The mass transportation function (τ

j,w

) represents a

percentage of the mass of element j added to or removed

from the system, in relation to the mass originally present in

the dolomitic itabirite, regardless of any volumetric change.

Thus, τ

j,w

<0 values represent losses of the element j in the

soft ore in relation to dolomitic itabirite, τ

j,w

=0 values

represent conservation, and τ

j,w

>0 represent gains, which are

absolute. The expression relative gain is used when an

element, although present at a higher concentration in the

altered material than in the protolith, shows τ

j,w

<0 or τ

j,w

=0

(Brimhall et al. 1985).

The averages of chemical composition and density of

nine samples of the protore and 37 samples of the soft ore

(Table 6) were used for the calculations. Titanium was the

element considered as immobile. The results of loss and

gain calculations in the protore–ore transition (Table 6)

show that during soft ore formation there is an almost

complete loss of Ca, Mg, and LOI (close to 100%). The

oxides SiO

2

and P

2

O

5

have been also, to a lesser extent,

leached, but P shows a slight relative increase, and MnO

2

shows 49% absolute gain. With respect to Fe, calculations

show that the gains are just relative, as there is a strict mass

conservation, i.e., this element shows the same behavior

that is assumed for Ti. Unfortunately, our analyses of most

trace elements in dolomitic itabirite or in soft ore are at or

near detection limits so that it is difficult to assess their gain

and losses during dissolution of dolomitic itabirite and

formation of the soft ore.

The calculated volume variation ("

i,w

)is−40.7%, which

means that the initial volume of the dolomitic itabirite

generates a volume of soft ore that corresponds to just

59.3% of this ore. The residual porosity of the ore is

calculated by means of the formula:

Porosity ¼ 1 ρ

w

ðÞ

=

ρ

calculated

ÞðÞ*100;ð

Bi <0.1 10 <0.1 24 1.2 <0.1 <0.1 2.2 <0.1

Th 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.5 10 0.4 0.4 0.1 1.5 24 0.5 0.1 0.1 <0.05 0.2 0.8 1.3 0.1 3.8 0.25 0.84

U 4.5 3.4 0.6 12.3 10 3.9 1.8 1.0 7.2 24 2.9 1.7 1.2 0.7 4.1 4.7 2.5 1.5 8.4 2.07 1.67

Au <2.0 8 <2.0 24 na <2.0 9.4 12.5 <2.0 35.0 na na

As 12.4 6.7 <5.0 23.1 10 13.6 6.6 3.9 28.4 24 9.3 7.4 1.6 5.5 9.6 16.0 6.4 9.2 26.3 6.55 4.80

Br <0.5 8 <0.5 24 na <0.5 <0.5 na na

Cr 65.3 59.5 <20.0 202.0 12 78.8 73.0 16.0 429.0 62 52.9 54.5 62.1 23.0 181.0 68.7 59.8 26.0 206.0 21.84 23.50

Ir <5.0 8 <5.0 24 na <5.0 <5.0 na na

Sb 4.0 1.7 2.0 6.9 10 3.2 1.3 1.4 6.1 24 1.6 5.5 4.2 2.9 14.0 4.9 3.8 1.8 14.0 1.35 1.52

Sc 0.5 0.3 0.1 1.0 8 1.1 0.9 0.4 3.5 24 na 0.2 0.1 <0.1 0.3 1.7 2.7 0.3 7.7 na na

Se <3.0 8 <3.0 24 na <3.0 0.0 1.5 1.5 <3.0 na na

Fe# 0.988 0.009 0.970 0.997 9 0.999 0.001 0.994 0.999 61 0.980 0.996 0.006 0.985 0.999 0.998 0.001 0.996 0.999 1.000 0.910

Fe

TOT

expressed as Fe

2

O

3

. Fe# = (Fe

3+

/(Fe

3+

+Fe

2+

). Data of the dolomitic itabirite are from Spier et al. (2006).

a

Au in ppb

na Not analyzed

Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254 245

where ρ

calculated

is the density that would be assigned to the

material if porosity were zero, which is estimated by the

weighted average of the density of its compo nents:

D

calc

¼ C

Fe

þ C

other

ðÞ

C

Fe

5:26 þ C

Si;Al

2:65

þC

Mn

=

4:7 þ C

Ca; Mg; LOI

2:9

where:

C

Fe

, C

Si

, C

Al

, C

Mn

, C

Ca

, C

Mg

,=chemical composition of

the element subscribed; C

other

=sum of the contents of the

other chemical components in the soft; C

LOI

=loss on

ignition of the soft ore and the numbers are values for

density for hematite, quartz, pyrolusite and dolomite,

respectively.

Electronic supplementary material Appendix D shows

bulk density, calculated density, and residual porosity values

for the soft ore samples. The bulk density varies from 2.46

to 3.66, averaging 3.05 g/cm

3

; the calculated density varies

between 5.05 and 5.20, averaging 5.13 g/cm

3

; and the

residual porosity, between 28.2 and 51.5%, averaging

40.5%.

Hard iron ores

Mineralogy and petrology

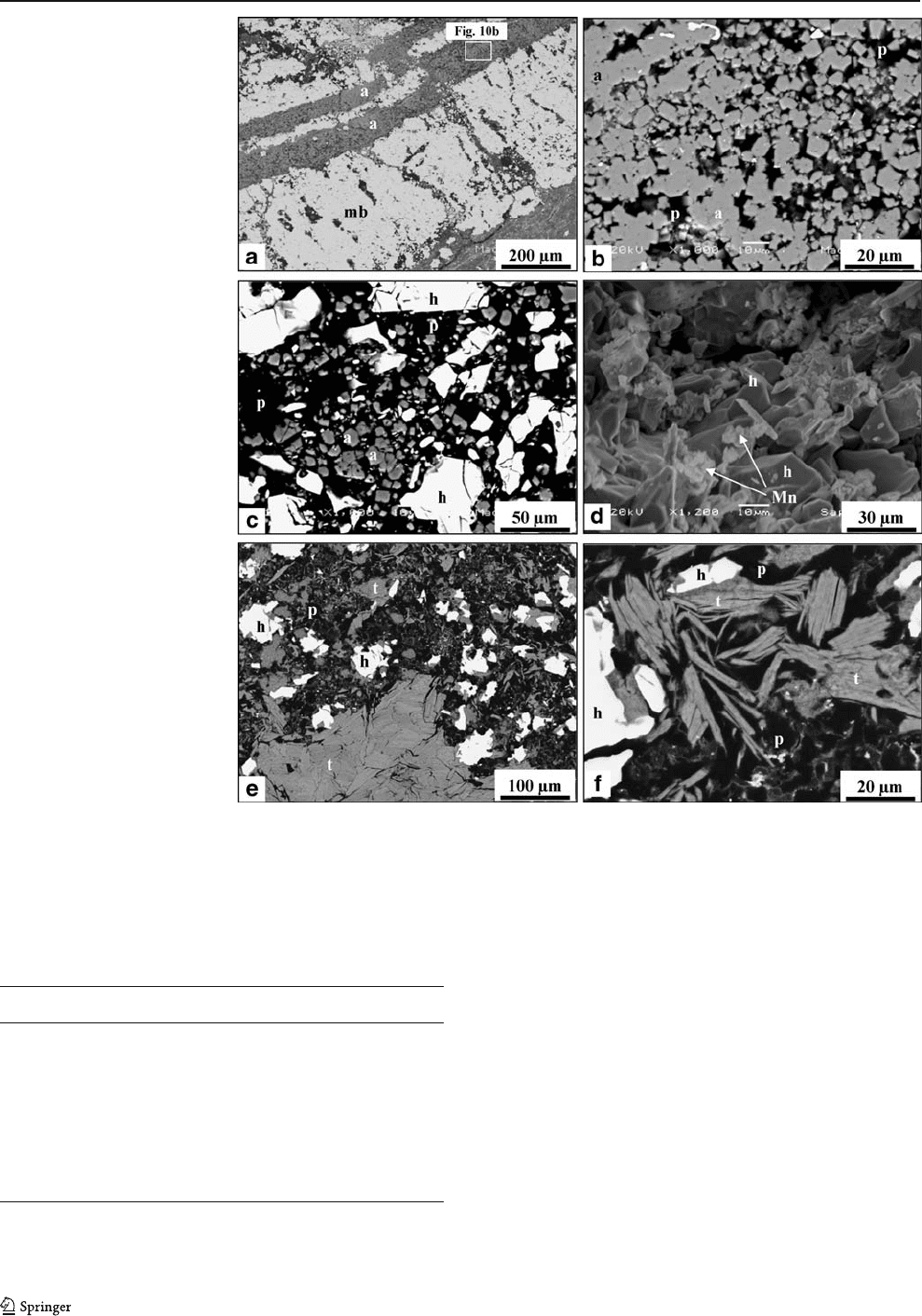

Petrographic and SEM observations of the massive,

banded, and schistose hard iron ores show a simple

mineralogical composition. The iron oxide mineralogy is

similar to that of the soft ore. Gangue minerals are very

rare, consisting of dolomite and, locally, apatite and talc. In

weathered hard ores, gangue minerals are generally absent,

creating a macroporosity defined by the pore spaces

between hematite crystals. In highly fractured orebodies,

goethite and kaolinite occur as thin films on the surface of

the ore. There is no difference in the mineralogical

composition of the three major subtypes of hard ore, except

in fabric and porosity.

Massive hard ore consists of tabular and granular

hematite (up to 80%) ranging in size from 5 to 30 μm

(average 20 μm), forming a granoblastic fabric (Fig. 13a,b).

Relics of martite (20 to 50 μm) with remnants of magnetite

occur between hematite crystals. Hematite overgrows

martite crystals. Porosity in hard massive ores varies from

Table 5 Average rare earth element composition

Hard ore

(n=10)

Soft ore Dolomitic itabirite

Bulk (n=24) Massive band

(n=6)

Porous band

(n=8)

Bulk (n=9) Iron-rich band

(n=6)

Dolomite-rich

band (n=6)

Ppm

La 1.06 3.50 0.85 6.65 2.65 1.85 3.13

Ce 1.88 6.42 1.58 11.95 4.21 3.00 6.24

Pr 0.28 0.98 0.20 1.70 0.53 0.39 0.76

Nd 1.34 4.36 0.90 7.35 2.40 1.71 3.41

Sm 0.36 0.98 0.20 1.72 0.57 0.39 0.77

Eu 0.14 0.40 0.07 0.74 0.22 0.14 0.32

Gd 0.53 1.27 0.28 2.56 0.74 0.48 0.99

Tb 0.09 0.23 0.04 0.46 0.13 0.08 0.17

Dy 0.55 1.51 0.30 3.10 0.86 0.54 1.11

Y 4.99 18.76 3.11 32.59 7.44 4.67 9.50

Ho 0.12 0.35 0.07 0.77 0.20 0.13 0.25

Er 0.34 1.12 0.24 2.53 0.63 0.43 0.78

Tm 0.05 0.18 0.04 0.41 0.10 0.07 0.11

Yb 0.28 1.17 0.24 2.59 0.62 0.42 0.71

Lu 0.04 0.19 0.04 0.43 0.10 0.07 0.12

ΣREE 6.96 22.66 5.04 42.94 13.86 9.63 18.76

La/Yb

PAAS

0.28 0.22 0.26 0.17 0.27 0.32 0.34

La/Sm

PAAS

0.46 0.52 0.61 0.53 0.61 0.69 0.60

Dy/Yb

PAAS

1.17 0.78 0.75 0.71 0.82 0.78 0.94

Ce :Ce

PAAS

0.82 0.80 1.04 0.76 0.86 0.82 0.89

Eu

Eu

PAAS

1.48 1.67 1.67 1.63 1.60 1.57 1.74

Pr

Pr

PAAS

1.02 1.09 1.01 1.12 1.00 1.01 1.00

Y

Y

PAAS

1.68 2.09 2.09 1.85 1.63 1.40 1.52

Eu

Eu

PAAS

¼ Eu

=

Eu

PAAS

ðÞ

=

Sm

=

Sm

PAAS

ðÞGd

=

Gd

PAAS

ðÞðÞ

1=2

, Ce

Ce

PAAS

, Pr

Pr

PAAS

and Y

Y

PAAS

calculated by similar way. Data of the

dolomitic itabirite are from Spier et al. (2006).

246 Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254

approximately 5 to 20%, and pore size from <1 to 50 μm.

Unweathered ores exhibit the lowest porosity of all hard

ores, around 3%, increasing up to 20% in weathered

samples.

Banded hard ore consists of alternating massive and

porous layers (Fig. 13c). Tabular and granular hematite are

the main iron oxides (up to 70%) with grain sizes ranging

from 5–20 μm. Hematite grows over martite or occur as

isolated crystals. Martite with relics of magnetite may occur

as individual crystals ranging from 30–50 μmorforming

dense aggregates, representing up to 5% of the volume.

Specularite (up to 5 vol.%) occurs locally, along shear planes

parallel to, or cutting, the banding and defining a discontin-

uously developed foliation. Porosity is highly variable in

banded iron ores, reaching up to 30% of the volume.

Schistose hard ore presents a lepidoblastic fabric which

is composed mainly of tabular hematite and specularite (up

to 70 vol.%) wrapping around porphyroclastic aggregates

of tabular and granular hematite (up to 50 vol.%, Fig. 13d).

Porosity in the schistose ore ranges from 5 to 20 vol.%.

Hematite was the only iron oxide identified by XRD in

samples submitted for MS analysis, with very sharp peaks.

These results are confirmed by the Mössbauer spectra

(Table 2 ). Sharp XRD peaks and Möss bauer parameters of

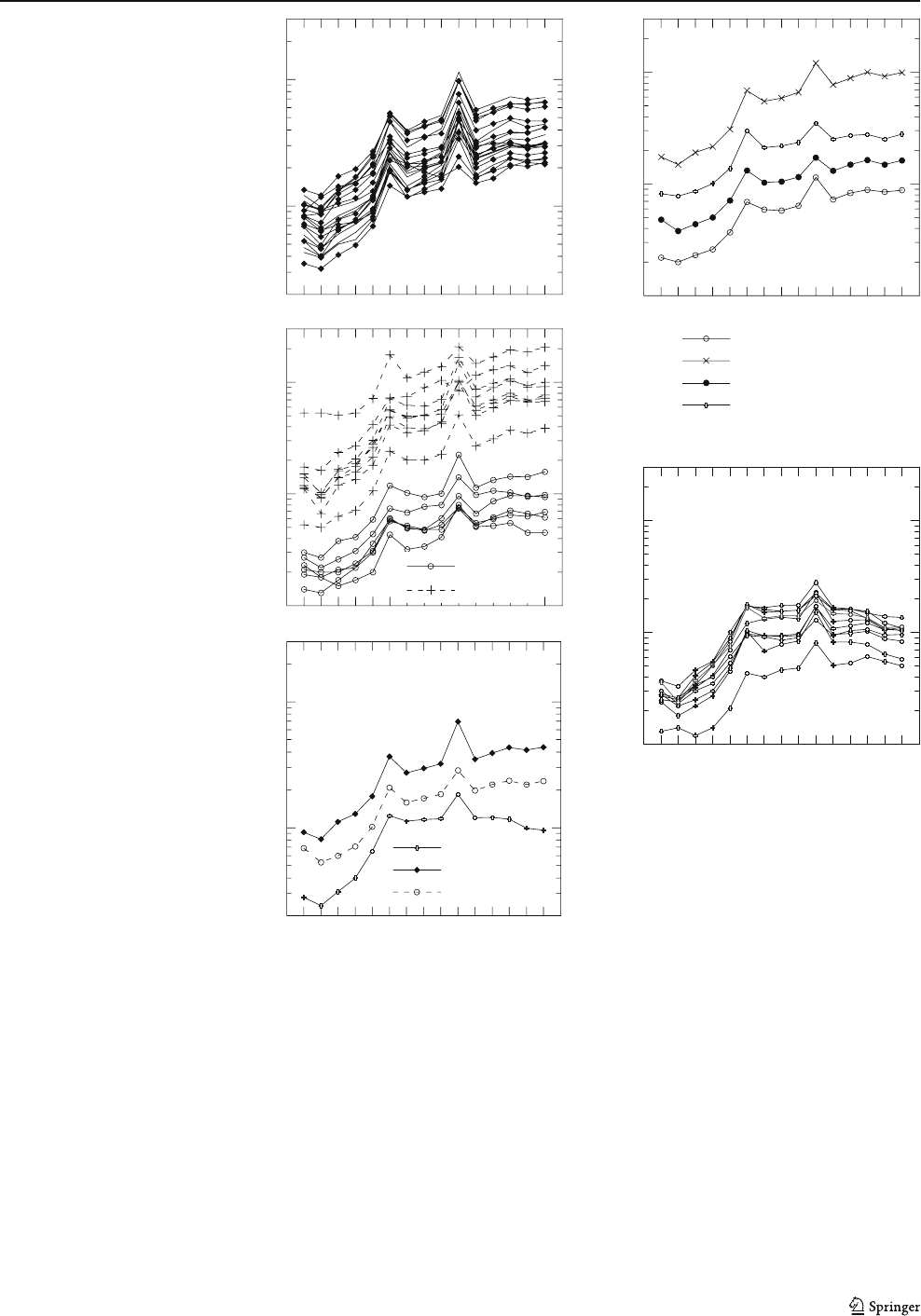

0.1

1

a

Sample / PAASSample / PAASSample / PAAS

Soft Ore

0.01

0.1

1

Massive band

Porous band

b

0.1

1

Hard ore

Soft ore

Dol. itabirite

La Ce Pr NdSmEuGd Tb D

y

YHoErTmYbLu

c

Average Ratios

0.01

0.1

1

La Ce Pr NdSmEuGd Tb Dy Y Ho Er TmYb Lu

Soft ore - massive band

Soft ore - porous band

Dol. itabirite - iron-rich band

Dol. itabirite - dolomite-rich band

Sample / PAAS

d

Average Ratios

0.01

0.1

1

La Ce Pr NdSmEuGd Tb Dy Y Ho Er TmYb Lu

Sample/ PAAS

e

Hard Ore

Fig. 12 PAAS-normalized

REEY data. a Soft ore. b

Massive and porous bands of the

soft ore. c Averaged iron ores

and dolomitic itabirite. d

Averaged massive and porous

bands of the soft ore and iron-

rich and dolomite-rich bands of

the dolomitic itabirite (protore of

the soft ore). Data for the

itabirites are from Spier

(2005). e Hard ore

Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254 247

hematite indicate a high degree of crystallinity, with little

heterogeneity. The unit c ell parameters of hematite in

samples MAC67 and MAC97, very similar to those of the

reference cell of hematite (Table 3), corroborate this

indication.

Geochemistry

The bulk geochemical composition of the hard ore is

simple, consisting almost entirely of Fe

2

O

3

(average

97.6 wt%; Table 4). The trace element composition of the

hard ore is also simple, with only Cr (average 65 ppm) and

V (average 35 ppm) showing average values higher than

30 ppm (Table 4).

The hard ore has low REE conten ts, with an average con-

tent of 7 ppm, ranging from 3 to 10 ppm. The REEY

PAAS

patterns are all similar (Fig. 12e), being characterized by a

strong depletion in light REE relative to heav y REE,

negative Ce

PAAS

anomalies (with the exception of sample

MAC68), marked positive Eu

PAAS

and Y

PAAS

anomalies,

and depletion of the heavy REE relative to the middle REE

(Dy/Yb

PAAS

>1).

Discussion

Comparison of the Águas Claras orebody with the Capão

Xavier and Tamanduá orebodies

Comparing the macroscopic features of the orebodies from

the Águas Claras, Capão Xavier and Tamanduá mines as

summarized in Table 7 (see Figs. 2aand5a,b), we notice that

the main differences between them are: (1) mineralogical

composition of the protore; (2) dominant types of ore, and

(3) importance of the structural control.

High-grade soft ores may form both from dolomitic

(Águas Claras and Capão Xavier) and siliceous itabirite

(Tamanduá). By comparing the average of the grades of all

samples collected during the operation of the Águas Claras

Mine (Spier et al. 2003) to the average of the grades from

Capão Xavier and Tamanduá (Table 1), we have verified

that although these ores formed from protore of different

mineralogical composition, the chemical composition of

soft ores is similar.

Hundreds of drill holes drilled in the Tamanduá Mine,

many of them passing through the orebody until they

Table 6 Mass balance calculations for the transition from dolomitic

itabirite to soft ore—Ti constant

Average composition Mass balance

(τ

j.w

)

Dolomitic itabirite

(n=9)

Soft ore

(n=37)

wt% wt% %

Fe

2

O

3

48.28 96.34 0

P

2

O

5

0.09 0.13 −28

Al

2

O

3

0.15 0.36 20

SiO

2

1.07 0.89 −58

MnO

2

0.34 1.01 49

CaO 16.17 0.21 −99

MgO 11.25 0.36 −98

TiO

2

0.01 0.02 0

LOI 22.95 0.82 −98

d (g/cm

3

) 3.62 3.05

Fig. 13 SE M b ackscattered

images and photomicrographs

of the hard ores. a, b Massive

hard ore, SEM image. c Banded

hard ore, reflected light, PPL.

Note alternation of highly

porous (pb) with less porous

bands (mb). d Schistose hard ore

showing porphyroclastic aggre-

gates of martite (with relics of

magnetite) and granular/tabular

hematite wrapped around by

porous and platy (specularite)

hematite, reflected light, PPL

248 Miner Deposita (2008) 43:229–254