Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Pretty Baby (1978) and later as a clam bar waitress in Atlantic

City (1981). In the latter film she washes her breasts with

lemons in a memorable scene. Her performance was rewarded

with an Oscar nomination for Best Actress. Aside from her role

in Paul Mazursky’s The Tempest (1982), which won her a Best

Actress Award at the Venice Film Festival, her next few films

were undistinguished, such as The Hunger (1983), in which she

and Catherine Deneuve costarred in a lesbian vampire film.

Appearing with

CHER

and Michelle Pfeiffer as the witches in

The Witches of Eastwick (1986), she more than held her own,

despite not getting the part she had been promised—it went to

Cher. Her next big role was in Bull Durham (1988) as a sexy

baseball fan who specializes in younger players, in this case

TIM ROBBINS

, with whom she became romantically involved

off screen (her marriage to Sarandon had ended in 1979 when

she became romantically involved with Malle).

Although her next three films did not do well at the box

office, one of them, White Palace (1990), brought her critical

praise. She played a hamburger waitress in love with a

wealthy, educated lawyer. Thelma and Louise (1991) was a crit-

ical and financial success, as well as being one of the most

controversial American films of its time. In what was proba-

bly the first female buddy road film, she and Geena Davis

play two women on the lam, defying the patriarchal estab-

lishment and attacking those things which men most wor-

ship, their sexuality and their vehicles.

Tim Robbins featured her in his directorial debut, Bob

Roberts (1992), a satire that spoofed a charismatic right-wing

politician (played by Robbins, who also wrote the screenplay).

That same year Sarandon made one of her most memorable

and significant films, Lorenzo’s Oil, playing a mother dedicated

to finding a cure for her son’s ALD (adrenoleukodystrophy), a

film that earned her Academy Award and Golden Globe nom-

inations for Best Actress. Another Academy Award nomina-

tion was forthcoming for her role in the John Grisham

adaptation The Client (1994), playing an attorney protecting

an 11-year-old who knows too much about the Mafia. She

also appeared that year in Gillian Armstrong’s film adaptation

of Little Women.

Perhaps Sarandon’s crowning achievement of the 1990s,

however, was her portrayal of Sister Helen Prejean in Dead

Man Walking (1995), a film that allowed the actress to work

as a powerful advocate for abolishing the death penalty in

America. This role resulted in an Academy Award for Saran-

don; her costar,

SEAN PENN

, was nominated for the Best

Actor Oscar and her partner Tim Robbins was nominated

for Best Director.

In 1998 Sarandon starred with

PAUL NEWMAN

and

GENE

HACKMAN

in the neo-noir thriller Twilight, directed by

Robert Benton, who also wrote the screenplay with Richard

Russo, which New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin consid-

ered “a class act in a classic genre,” adding that “Sarandon

doesn’t have to fake glamour, she does it here with sinuous

allure.” The same year she starred in Stepmom and held her

own against

JULIA ROBERTS

in this weepie.

An even greater variety of roles awaited Sarandon. She

costarred with Natalie Portman in the Wayne Wang family

comedy Anywhere but Here (1999). When Tim Robbins wrote

and directed Cradle Will Rock (1999), dramatizing the cre-

ation and performance of Marc Blitzstein’s left-wing musical

during the Great Depression, the all-star cast included

Sarandon. She was also featured in another quirky and eccen-

tric film, Stanley Tucci’s Joe Gould’s Secret (2000), as the artist

Alice Neel, who painted Gould, an eccentric denizen of

Greenwich Village, with three penises, metaphorically sug-

gesting Gould’s creativity. The film was more a critical suc-

cess than a commercial one—it grossed less than $1

million—but, at that stage in her career, Sarandon could well

afford to take chances on commercially risky projects.

Also in 2000 Sarandon provided the voice of Coco La

Bouche in the animated movie Rugrats in Paris, which earned

more than $71 million at the box office.

satire on the screen Playwright George S. Kaufman

once described satire as “that which closes on Saturday

night.” The intelligent use of wit and irony to cut fools and

folly down to size has rarely been an audience pleaser among

those seeking simple entertainment, whether in the theater

or at the movies. Relatively few out-and-out satirical films

have been made, and few of these have been box-office win-

ners. Ironically, many of the best satires—whether or not

they succeeded with the public in their day—tend to stand up

very well decades later.

The satiric tradition began in earnest in the early 1930s

when America was in the grip of the Great Depression.

There was certainly plenty to satirize in those bleak days, and

FRANK CAPRA

was among the first to capitalize on popular

discontent in American Madness (1932). Later in that decade

Nothing Sacred (1937) poked fun at American gullibility. But

nobody satirized American society or its institutions better

during the 1930s than the

MARX BROTHERS

, who attacked

everything from higher education in Horsefeathers (1932) to

government and war in Duck Soup (1933).

The leading movie satirist of the 1940s was unquestion-

ably writer-director

PRESTON STURGES

, whose hit comedies

made fun of politics, in The Great McGinty (1940), for which

Sturges won a Best Original Screenplay Oscar; marriage, in

The Palm Beach Story (1942); and small-town American val-

ues, in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1943). In the case of

Sturges and many others who were successful with satire, the

biting humor of their films seemed less satirical than merely

zany with an acerbic touch.

Hollywood took itself very seriously during the late 1940s

and 1950s and there were very few satires during those years.

The postwar era and early cold-war years were filled with

such angst that most comedies, as an antidote, tended to be

extremely light. Even when Nothing Sacred was remade in

1954, it was designed as an innocuous vehicle for Martin and

Lewis and renamed Living It Up. One major exception to the

rule was

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947), a film

so bleak in its harsh humor, satirizing, as it did, religion and

justice, that it brought cries of outrage, and many theaters

refused to run it.

The tumultuous 1960s saw the return of the satire with

surprising box-office strength. The rise of the counterculture

SATIRE ON THE SCREEN

358

and a shift in the focus of the movies toward a younger, less

conservative, baby-boom audience allowed films to be outra-

geous. Among the filmmakers who responded were

STANLEY

KUBRICK

, whose Dr. Strangelove (1964) satirized the military

and the threat of nuclear destruction with pungent black

humor. Later in the decade, The President’s Analyst (1967)

took potshots at everything from the government to the

phone company with hilarious results.

The leading film satirist of the 1970s was screenwriter

PADDY CHAYEFSKY

, whose angry comedies were noted for

both their humor and their truth. His screenplays for the hits

The Hospital (1971) and Network (1976) were winners; the lat-

ter movie brought him an Oscar for Best Screenplay. Other

notable satires during the decade were the powerful Catch-22

(1970) and Little Murders (1971), plus the mild Fun with Dick

and Jane (1977).

The self-indulgent 1980s should have provided fertile

ground for satirist filmmakers, but the offerings were sur-

prisingly lean from mainstream directors. Satire bubbled up

with a vengeance, however, from the underground cinema,

most notably in the work of writer-director John Waters,

who made such iconoclastic social satires as Polyester (1981)

and Hairspray (1988).

John Waters continued to work during the 1990s, direct-

ing Serial Mom (1994), for example, which spoofed good

manners, and Pecker (1998), which pokes fun at his native

Baltimore, Catholics, gays, straights, upper-class mores, art

dealers, and art criticism.

MEL BROOKS

should not be overlooked as a master Hol-

lywood satirist whose films spoofed Hitchcock (High Anxiety,

1977), westerns (Blazing Saddles, 1974), horror films (Young

Frankenstein, 1974, and Dracula: Dead and Loving It, 1995),

space exploration (Spaceballs, 1987), and the Robin Hood leg-

end (Robin Hood: Men in Tights, 1993). Another spoof of space

travel (and especially the Star Trek series), was Galaxy Quest

(1999), which featured Tim Allen as a William Shatner clone

whose popularity as a television star has come and gone but

who gamely soldiers on at Galaxy Quest conventions, until

he is kidnapped by some really goofy aliens; he is given a

command post for a command performance, fighting against

his evil adversary, Sarris (a left-handed tribute to the Village

Voice film critic Andrew Sarris). Alan Rickman was especially

brilliant as the Spock clone, a disgustingly hammy, self-

important actor.

ROBERT ALTMAN

was also in great satiric form during the

1990s, as evidenced by his Hollywood satire The Player (1992)

and by Ready to Wear (1994), which spoofed the world of high

fashion. An example of high-flown satire about the British

aristocracy is Gosford Park (2001); it also echoed the satire of

Jean Renoir in Rules of the Game (1939), as French critics were

quick to notice. The film made more than $30 million and

was graced by an excellent cast headed by Eileen Atkins; the

incomparable Maggie Smith, playing an aristocratic lady with

a heart of lead; and Michael Gambon as Sir William McCor-

dle, who ends up dead, and for good reason.

For political satire,

WARREN BEATTY

scored points with

Bulworth (1998), but

BARRY LEVINSON

was far more success-

ful with Wag the Dog (1997), a film in which White House

officials hire a Hollywood producer to create a war to shift

the attention of the media from accusations of presidential

fondling.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN

, playing the Hollywood pro-

ducer, was nominated for an

ACADEMY AWARD

.

The foremost current satirical talent in Hollywood, how-

ever, is Christopher Guest, as evidenced by Waiting for Guff-

man (1996), which spoofed community theater. This cult

classic was followed by Best in Show (2000), which spoofs dog

shows; then came A Mighty Wind (2003), which spoofed folk

groups from the 1960s. In all of these films, Guest draws on

the improvisational talents of a repertory group of actors

including Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara, Parker Posey,

Bob Balaban, and Fred Willard. In a way, A Mighty Wind was

a reprise of This Is Spinal Tap (1984), the film

ROB REINER

directed and Guest wrote and appeared in, getting his start

before going on to pursue the “mockumentary” genre.

A satirist working mainly in the documentary genre is

Michael Moore, who took on General Motors in Roger and

Me in 1989 by trying to ambush Roger Smith of GM to ask

him about plant closings in the Flint, Michigan, area. Cana-

dian Bacon, a feature film, followed in 1994, and The Big One

in 1998, another CEO-baiting exercise, this time targeted at

Nike boss Phil Knight. Moore’s 2002 satiric attack, directed

at the American fondness for guns and the NRA, was Bowl-

ing for Columbine. Michael Moore is Hollywood’s most polit-

ical and most outspoken critic of conservative, capitalistic

America.

See also

BLACK COMEDY

.

Sayles, John (1950– ) A quirky writer-director of

independent motion pictures who has carved a niche for him-

self as a creator of low-budget movies for the art-house audi-

ence. A former novelist and award-winning author, he has

approached the movie business with refreshing resourceful-

ness and humor—and has even managed to create a modest

reputation for himself as an actor in many of his own films.

Born to a family of educators, initially Sayles was more

interested in sports than in writing. He once said, “Most of

what I know about style I learned from Roberto Clemente.”

Nonetheless, after doing some college acting, he eventually

embarked on a writing career, penning two acclaimed novels,

Pride of the Bimbos and Union Dues. He also won two O.

Henry awards for short stories.

On the basis of his unusual writing style,

ROGER CORMAN

hired Sayles to write the screenplay for a low-budget rip-off

of Jaws (1975) called Piranha (1978), in which Sayles was also

given a small acting role. Critics noted that the film, for all its

foolishness, was cleverly written. Meanwhile, Sayles contin-

ued to learn his new craft on-the-job by writing the scripts for

The Lady in Red (1979) and Battle beyond the Stars (1980).

In the late 1970s, Sayles decided to use his $40,000 in sav-

ings (earned from his work-for-hire screenwriting) to make a

film of his own. The result was The Return of the Secaucus

Seven (1980), a forerunner of The Big Chill (1983) and a film

that delighted the critics, becoming a sleeper hit on the art-

house circuit. To pay fully for its production, however, Sayles

had to come up with another $20,000, which he earned by

SAYLES, JOHN

359

writing the TV movie A Perfect Match (1980), and the low-

budget feature films The Howling (1981) and Alligator (1981).

The success of Secaucus Seven allowed Sayles to raise

$300,000 (a very minor sum by movie standards) to make

Lianna (1983), a courageous, thoughtful drama about les-

bianism. In that same year, Sayles won the MacArthur Foun-

dation “genius” award, which granted him $30,000 tax-free

every year for five years.

His growing reputation as a filmmaker earned him studio

backing for his third film, Baby, It’s You (1983), a movie made

with a $3 million budget. It received mixed reviews and was

not a major commercial success.

Sayles went back to independent filmmaking, preferring

to have greater control of his projects, and proceeded to

make such provocative and highly regarded movies as The

Brother from Another Planet (1984), Matewan (1987), and

Eight Men Out (1988).

During the 1990s, Sayles became an even more visible

independent director. Most remarkable during that decade,

perhaps, was Lone Star (1996), a finely honed character study

set on the Mexican border, which he both wrote and directed,

and which was nominated for an Oscar for the screenplay.

This was his second nomination for screenwriting during the

1990s, following an earlier nomination for Passion Fish

(1992). City of Hope (1991) has been considered the director’s

most ambitious film to date in the way it attempts to anato-

mize American urban life. By contrast, The Secret of Roan Inish

(1995), set in Ireland and combining Celtic myth and realism,

has been considered his gentlest film. Sayles not only wrote

and directed the movie, but he also edited it. He also wrote,

directed, and edited Men with Guns (1998), set in an unnamed

Central American country and involving the initiation of an

idealistic physician who believes that he has been helping the

country by training other doctors but discovers that his

physician students have in fact been murdered. Limbo (1999)

was another typically offbeat Sayles project, involving the

exploitation of America’s last frontier and offering an

ambiguous, open-ended conclusion about losers in Alaska.

His first project of the new century was Sunshine State (2002),

which Sayles wrote and directed. Sayles has also acted, not

only in his own films such as City of Hope but also in the fea-

tures of other independent filmmakers, the most notable of

which was Gridlock’d (1997), directed by Vondie Curtis-Hall.

scandals American royalty doesn’t reside in Washington;

it reigns from Hollywood, where the rich, powerful, and

famous frolic both in the sun and the public eye. Ultimately,

in true democratic fashion, it is the American people who

make or break the kings and queens of Tinsel Town, and the

perpetual scandals that rock the film industry destroy only

those whom audiences have grown tired of. But nothing sells

newspapers and magazines like a scandal, and the stars, with

their inflated bank accounts and often equally inflated egos

and passions, have given the scribes plenty to write about.

There have been scandals concerning all sorts of pecca-

dillos, but, until recently, sex has been number one. Mary

Astor’s diary made headlines when it was submitted as evi-

dence in her mid-1930s divorce proceedings. It went into

great detail about her adulterous sexual liaisons with a num-

ber of famous men, including playwright George S. Kauf-

man. But Astor not only survived the scandal; she later

flourished as a femme fatale in

THE MALTESE FALCON

(1941)

and enjoyed a long career in character roles, as well.

Audiences have rarely been outraged by sexual excesses as

long as no one gets hurt. In fact, film fans have rather enjoyed

sex scandals, getting a vicarious thrill from the escapades of

such stars as

ERROL FLYNN

and

MARILYN MONROE

—espe-

cially when they have been compatible with the on-screen

image of the actor involved. In Flynn’s case, it mattered little

that he was brought to trial for statutory rape. Once he was

acquitted of all charges, his devil-may-care attitude was con-

doned by the public, and the expression “in like Flynn”

entered the language as a euphemism for sexual conquest. As

for Monroe’s famous nude calendar, it didn’t hurt her at all; it

actually helped turn her into a star.

In contrast to the likes of Flynn and Monroe, actors and

actresses who are perceived to be innocent tend to be hurt

much more by scandalous publicity. In addition, when either

children or other innocent parties are involved in a scandal,

the repercussions are often quite severe. One need only think

SCANDALS

360

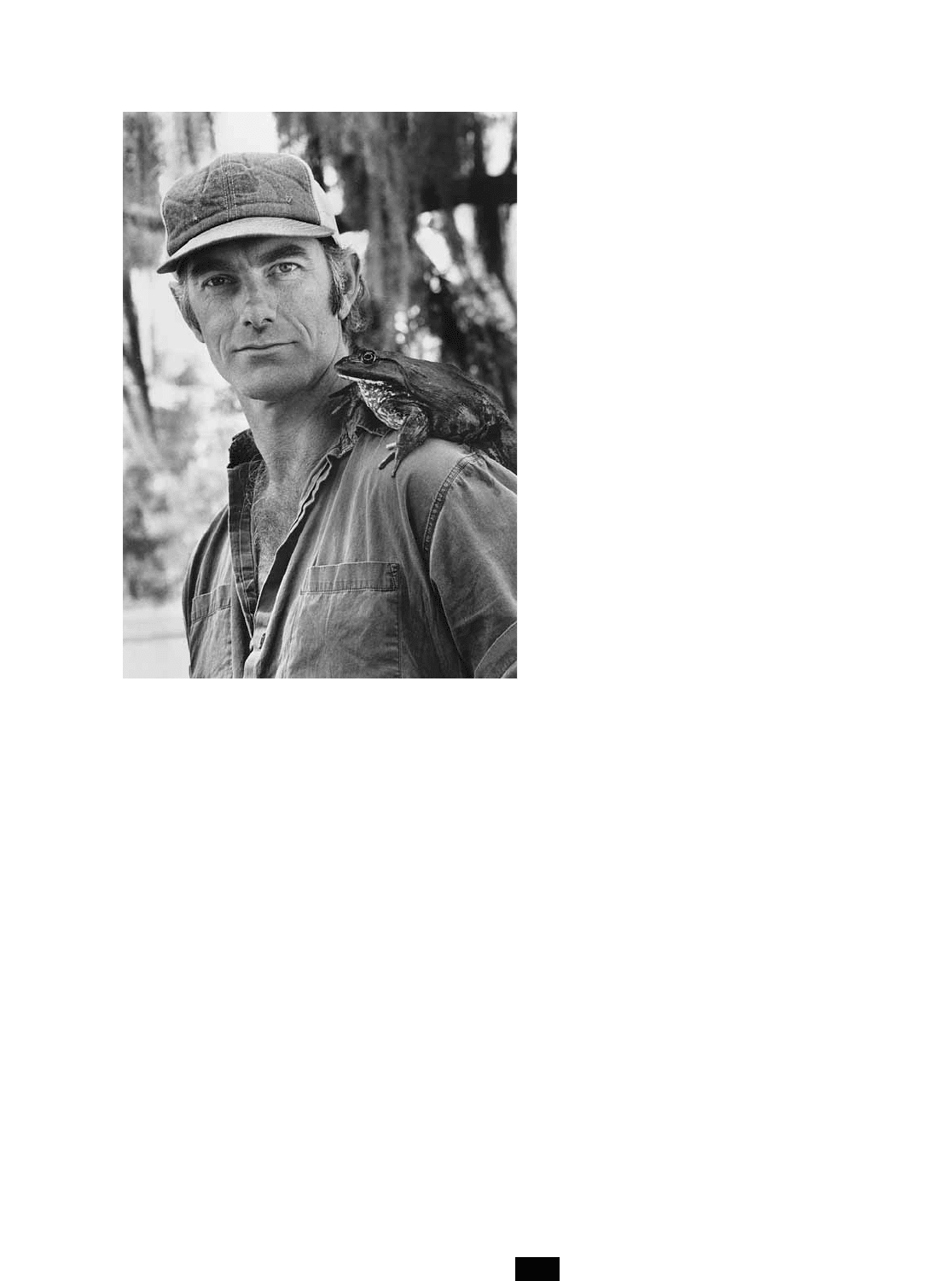

John Sayles on location for Passion Fish (1992) (PHOTO

COURTESY MIRAMAX FILMS)

of the outcry against

INGRID BERGMAN

when she left her

husband and child for director Roberto Rossellini. Her

career was temporarily shattered, and it took quite some time

for American audiences to forgive and forget. Another exam-

ple of this phenomenon was the

ELIZABETH TAYLOR

–Eddie

Fisher marriage. When Fisher left his then wife,

DEBBIE

REYNOLDS

, for Taylor, the world sympathized with the

wronged wife who had been done in by her close friend Liz.

Ironically, when Taylor humiliated Fisher with her highly

publicized affair with

RICHARD BURTON

on the set of Cleopa-

tra (1963), there was little public sympathy for Fisher, who

most watchers felt deserved what he got for leaving Debbie

Reynolds in the first place.

Sex is one thing, but murder is quite another. When the

two are combined in a scandal, the result is often a ruined

career. Among the most famous sex-and-murder scandals was

the 1921 “

FATTY

”

ARBUCKLE

case. He had been accused of

rape and manslaughter in the death of Virginia Rappe, but

although he was acquitted on all counts, the publicity result-

ing from the trial ruined him. Unlike Errol Flynn, Arbuckle

was seen not as a dashing man-about-town but as a mon-

strous villain. His crime was that he was not the same man

offscreen as he was on, and audiences made him pay for the

“duplicity” with his career.

On the heels of the Arbuckle case was yet another mur-

der case with sexual overtones. William Desmond Taylor, a

handsome and charismatic director, was shot and killed in his

palatial mansion. When it became known that two popular

actresses,

MABEL NORMAND

and Mary Miles Minter, had

both been his lovers and had seen him the day of his death,

they suddenly found their fame and glory compromised.

Though neither actress was ever accused of the killing—in

fact, no one was ever brought to trial—their names were

dragged through the mud and the mud stuck.

Another victim of a mysterious end was the powerful

director-producer

THOMAS H

.

INCE

. He supposedly died of

“heart failure brought on by acute indigestion” while on

William Randolph Hearst’s yacht in 1924. Rumor had it that

Hearst shot and killed Ince because of the director’s dal-

liance with the newspaper magnate’s mistress, Marion

Davies. Though an investigation was belatedly made by the

authorities, it was quickly dropped, some say because of

Hearst’s immense clout. Because of Hearst’s control of the

media, the scandal was very much underground and was kept

alive in whispers.

There are some Hollywood scandals involving sex and

murder that are more shocking than titillating. In 1958,

LANA TURNER

’s daughter, Cheryl Crane, stabbed mobster

Johnny Stompanato to death, claiming she was defending her

mother. The nation took pity on the young girl, and despite

Turner’s intimate association with Stompanato, audiences

preferred to think of Turner as having simply fallen for the

wrong man; her career didn’t suffer.

Most Hollywood scandals involve private events that

become public knowledge. A rare on-set scandal that shocked

the industry in the 1980s took place during the making of

Twilight Zone, The Movie (1983), when actor Vic Morrow and

two children were killed in a helicopter accident. The direc-

tor of the segment,

JOHN LANDIS

, was brought to trial on

charges that he had been careless and reckless in the shoot-

ing of the helicopter scene and was therefore responsible for

the three deaths. Landis was acquitted and has continued to

direct, but his once hot career has never been quite the same.

When a major star dies under mysterious circumstances,

that kind of scandal never fully disappears. Marilyn Monroe’s

sexual involvement with President John F. Kennedy and,

later, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, has been well

documented. Robert Kennedy’s possible role in her death in

1963, however, remains one of Hollywood’s most enduring

scandals because it links the two scandal capitals of America,

Hollywood and Washington, as well as the most charismatic

actress and politicians of our time.

The Hollywood/Washington connection has evolved a

great many other scandals besides

MARILYN MONROE

’s.

JANE

FONDA

’s visit to North Vietnam during the Vietnam War of

the 1960s and early 1970s provoked accusations of treason

from a large segment of the American public. She survived in

Hollywood because the moviegoing public was generally

young and antiwar. But during the red-scare years of the late

1940s and early 1950s, even a movie idol as beloved as

CHAR

-

LIE CHAPLIN

was hounded out of America because of his left-

ist political beliefs, and that came after he had overcome the

scandals of a lurid divorce case, a paternity suit, and a federal

morals charge.

Hollywood, itself, suffered one of its worst scandals

when, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the House Un-

American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigated com-

munist infiltration of the movie industry. At the time of the

scandal, it seemed that there were, indeed, a number of com-

munists among writers, directors, and actors in Hollywood.

With hindsight, however, the real scandal was that hundreds

of innocent lives were ruined by innuendo and unsubstanti-

ated charges. The insidious blacklist was the outgrowth of

the HUAC hearings, and the damage that list wreaked on

Hollywood was incalculable.

Due to a far more permissive society, genuine scandals

have been hard to come by in recent decades. Actors involved

in illicit sex, having children out of wedlock, and becoming

drug addicts aren’t big news. Sexual conduct is merely a mat-

ter of gossip, not scandal, and celebrity drug addicts

announce their treatment at the Betty Ford Clinic almost as

a rite of passage. Perhaps the only recent scandal concerning

drugs in Hollywood was 13-year-old Drew Barrymore’s

admission that she had an alcohol and drug problem that

began when she was nine years old.

Perhaps the only potential ingredient for scandal that can

really shake the jaded members of the film industry is the one

that fuels all their other passions: money. When the then-

president of

COLUMBIA PICTURES

, David Begelman, was pros-

ecuted for forging checks in the late 1970s, there were

headlines and headshaking. The scandal toppled Begelman

from his perch—for all of four months. The actor who blew the

whistle on Begelman,

CLIFF ROBERTSON

, didn’t work again for

three and a half years. But that was another, quieter, scandal.

During the 1990s, the bottom-feeding tabloids kept

exploiting scandalous behavior in Hollywood and elsewhere.

SCANDALS

361

With the end of the studio system and the deaths of the

major gossip columnists, in addition to a more liberal attitude

toward sexual indiscretions and a more tolerant attitude

toward moral peccadilloes, people seemed less concerned

about the behavior of Hollywood celebrities. A gifted young

actor, Robert Downey Jr., who played Charlie Chaplin so

well in Sir Richard Attenborough’s film of 1992, has had con-

tinuing problems with drug addiction, for example, but that

sort of “scandal” no longer seems very important, merely

unfortunate. When another gifted young actor, River

Phoenix, died of a drug overdose at the age of 23 in 1993, the

news seemed more tragic than scandalous.

Madonna has indulged in scandalous behavior, but most

people dismiss her shenanigans as self-promoting publicity

stunts. No Hollywood personalities approached the magni-

tude of the O. J. Simpson scandal of the mid-1990s and the

subsequent trial.

NICK NOLTE

received a citation for driving

under the influence in 2003, but no one cared.

WINONA

RYDER

was caught shoplifting in 2002 but scandals are sim-

ply not what they used to be.

Schary, Dore (1905–1980) He rose from lowly con-

tract scriptwriter of “B” movies to become the head of MGM.

Along the way, he won an Oscar for his writing, became an

executive producer, and was the vice president in charge of

production at not one, but two, major studios. Schary is per-

haps best known for spearheading, along with

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

, the rush into “message” movies in the late 1940s

(i.e., films dealing with social issues such as bigotry) and

replacing

LOUIS B

.

MAYER

at the helm of MGM in 1951.

Schary’s original ambition was to become an actor, and he

reached Broadway when he was just 25, playing a supporting

role in The Last Mile. Fancying himself a writer, he also

worked as both a journalist and a playwright, with little suc-

cess in either field. He had done enough writing, however, to

latch on in Hollywood as a screenwriter, penning such “B”

movies as He Couldn’t Take It (1932), Chinatown Squad (1935),

and Silk Hat Kid (1935).

Schary landed in the big leagues when he began to write

for MGM, sharing a Best Original Story

ACADEMY AWARD

with his cowriter, Eleanore Griffin, for Boys Town (1938). He

continued writing but showed even more promise as a pro-

ducer, and so he was promoted to the post of executive pro-

ducer of MGM’s “B” movie list. Opinionated and strong

willed, he quit after a fracas and went to work for

DAVID O

.

SELZNICK

, producing such films as The Spiral Staircase (1946)

and Till the End of Time (1946).

Schary kept rising up the Hollywood ladder, being named

head of production at the troubled RKO studio. He hoped to

bring RKO back from the edge of bankruptcy, and he was off

to a good start with Crossfire (1947), a sleeper hit and one of the

first movies about prejudice to be made by Hollywood. It came

out the same year as Gentleman’s Agreement, and the two films

started a rash of “adult” message movies. Unfortunately, not

long after Schary arrived at RKO,

HOWARD HUGHES

bought

the company. Far too liberal in his politics for the extremely

conservative Hughes, Schary was quickly out on his ear.

But again, Schary found himself being kicked higher up

the ladder. Due to skyrocketing costs at MGM,

NICHOLAS M

.

SCHENCK

, the president of MGM–Loew’s, insisted that

LOUIS B

.

MAYER

find a new

IRVING THALBERG

to oversee the

production process and boost MGM profits. With Schenck’s

blessings, Mayer picked Schary in 1947.

During the next four years, it was war between Mayer and

Schary, with Schenck often having to act as peacemaker.

Meanwhile, in the face of inroads from TV, Schary was effec-

tively doing his job as head of production. He was also pro-

ducing hits such as Battleground (1949). In 1951, when Mayer

finally forced Schenck to pick between Schary and the man

whose name was part of the title of the company, Schenck

stunned both Mayer and Hollywood by choosing Schary.

During the next five years, Schary ran MGM until the

company posted its first losing year in its entire history in

1956. He was promptly fired. He went back to Broadway,

which he had left with his tail between his legs nearly 25

years earlier, and wrote and produced the critically acclaimed

hit Sunrise at Campobello, which was later turned into a 1960

movie with a Schary screenplay. He continued to dabble in

the movies during the late 1950s and early 1960s, scripting

and producing such films as Lonelyhearts (1959) and Act One

(1963), which he also directed.

A longtime liberal activist, Schary was one of the few

major studio heads to speak out against the Hollywood black-

list in the early 1950s. In fact, his left-leaning attitudes were

so well known that gossip columnist Louella Parsons once

referred to MGM in print as “Metro-Goldwyn-Moscow”

during the height of the red-baiting era. Staunch in his beliefs,

however, Schary withstood the attacks and in his later years

became a well-known defender of civil and human rights.

Schenck, Joseph M. (1878–1961) and Nicholas M.

(1881–1969) Two brothers who, between them, at one

time wielded more power in Hollywood than anyone. The two

brothers controlled two of the five major studios, with Joseph

as chairman of the board of

TWENTIETH CENTURY

–

FOX

and

Nicholas as president of the theater chain and parent company

of MGM, Loew’s, Inc. Though neither man was well known

to the public at large, within the industry they were the equiv-

alent of royalty.

Both brothers were born in Rybinsk, Russia, arriving in

the United States when they were small children. Joseph, the

elder of the two, became a pharmacist and then, with his

brother, bought several drugstores. Again it was Joseph, ever

the risk taker, who convinced his kid brother to join him in a

new venture, opening up an amusement park at Fort George

in upstate New York. Later, in 1912, they joined with Marcus

Loew in buying the famous Palisades Amusement Park in

New Jersey.

During these years, Loew was building his theater chain,

and he invited the two brothers into his business, making

them senior executives. They took to the theater business like

racehorses on a fast track, helping to build the Loew’s chain

into one of the most powerful in the country. But it was

Nicholas who continued the job for Loew, staying with the

SCHARY, DORE

362

company until 1956, becoming president upon his mentor’s

death in 1927. Nicholas was instrumental in the acquisition

of MGM in 1924, and he was the power and the financial

brains behind the studio’s ascent to the top of the heap dur-

ing the 1930s through the early 1950s. It was Nick Schenck

to whom

IRVING G

.

THALBERG

and

LOUIS B

.

MAYER

had to

answer. When he was no longer pleased with Mayer’s reign

on the West Coast, he replaced him with

DORE SCHARY

.

When that move failed to stem MGM’s fall from grace,

Schenck, himself, was forced into the figurehead position of

chairman of the board in 1955, retiring the following year

from the company that he had guided to preeminence.

Joseph Schenck took a different route to Hollywood

power. Unlike his brother who ruled from the East Coast,

Joseph “went Hollywood,” quitting Loew’s in 1917 to

become a producer, and he was a successful one from the out-

set, producing the films of a tightly knit group of talented and

popular performers, including those of his wife, Norma Tal-

madge (whom he married in 1917), as well as the films of the

other Talmadge sisters, Constance and Natalie. In addition,

he produced “

FATTY

”

ARBUCKLE

’s popular films, and those of

Arbuckle’s buddy (and Natalie Talmadge’s husband), the

great

BUSTER KEATON

, including all of the “Great Stone-

face’s” most important and successful movies.

Joseph Schenck was the man everyone turned to in Hol-

lywood to get things done. When the founders of

UNITED

ARTISTS

,

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS

,

MARY PICKFORD

,

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

, and

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

, needed the strong hand of

management to keep their enterprise afloat, they turned to

Schenck to become the company’s chairman of the board.

Later, when Darry F. Zanuck left Warner Bros., he went to

Schenck to get the backing to form a new company during

the depths of the Depression. So, Twentieth Century was

formed in 1933, later to merge with Fox in 1935, at which

time Schenck became chairman of the board of

TWENTIETH

CENTURY

–

FOX

, a post he held until 1941 when he went to

prison for four months in a tax and payola scandal.

He returned to his studio as executive producer but made

few films of distinction. Among his minor accomplishments

during the late 1940s and early 1950s was befriending

MARI

-

LYN MONROE

, who was known to be one of his “girlfriends.”

He helped her during her early years at

FOX

and was later

instrumental in getting her a contract at

COLUMBIA

.

Hollywood ignored Schenck’s prison record and later

honored him in 1952 with a special

ACADEMY AWARD

“for

long and distinguished service to the motion picture indus-

try.” But the risk taker was not quite ready to sit on his laurels.

He promptly joined with Michael Todd in forming the Magna

Corporation in 1953 to publicize and sell the new widescreen

process, Todd-AO, to both the industry and the public.

By the end of the 1950s, both Joseph and Nicholas

Schenck had come to the end of their movie careers.

Schrader, Paul (1946– ) An intense screenwriter and

director whose films are often challenging and controversial.

Schrader intends to entertain, but his films are never mind-

less excursions into fantasy; unlike many Hollywood writers

and directors, he rarely makes concessions to the market-

place. For the most part, he has been far more successful as a

screenwriter than as a writer-director. In particular, his tal-

ents have been best brought out through his collaboration

with strong, independent directors such as

BRIAN DE PALMA

and

MARTIN SCORSESE

.

Raised as a strict Calvinist, Schrader saw his very first film

at the age of 18. After graduating from Calvin College, he

traveled to Los Angeles and took an M.A. degree from

UCLA. Falling in love with the movies, Schrader eventually

became a film critic for the L.A. Weekly Press and also served

as editor of Cinema Magazine. In 1972, his book Transcenden-

tal Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dryer was published.

Meanwhile, Schrader toiled at writing screenplays, finally

hitting it big when (in collaboration with Robert Towne) he

sold The Yakuza (1974) for a reported $400,000. It was an

important sale because it highlighted a new trend in Holly-

wood for paying large sums of money for original screen-

plays. The Yakuza, however, was a flop at the box office.

Schrader quickly became a hot screenwriter, though,

when he penned two major hits, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Dri-

ver (1976) and Brian De Palma’s Obsession (1976). The success

of these two films gave Schrader the clout to shoot his own

screenplay of Blue Collar (1977), a critically applauded movie

that did not do great business.

Moving back and forth between strictly writing and writ-

ing and directing, Schrader has amassed an impressive body

of work. His movies are often violent and harsh, dealing with

both the physical and psychological underworld. Though he

has rarely had commercial success as a writer-director, his

films, such as Hardcore (1978), American Gigolo (1979), and

Mishima (1985), have been consistently compelling. His

direction of other writers’ work in Cat People (1981) and Patty

Hearst (1988) is also strong and provocative. Yet it is his

screenwriting, with films such as Raging Bull (1980), The Mos-

quito Coast (1986), and Scorsese’s controversial masterpiece,

The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), that has marked

Schrader as a major Hollywood talent.

During the 1990s, Schrader continued to write screen-

plays and direct films. He teamed with

SYDNEY POLLACK

for

the Cuban feature Havana (1990), starring

ROBERT REDFORD

as a gambler seeking his fortune in Castro’s Cuba. In 1991, he

directed The Comfort of Strangers, a psychological thriller that

was scripted by Harold Pinter and starred Christopher

Walken, Natasha Richardson, and Helen Mirren. Schrader,

who had probed the dark underside of New York City in his

script for Taxi Driver, returned to Manhattan in Light Sleeper

(1992), which he wrote and directed for

SUSAN SARANDON

and Willem Dafoe.

DENNIS HOPPER

played the lead for

Schrader in Witch Hunt (1994). In 1995, Schrader scripted

another New York story for director Harold Becker in the

AL

PACINO

film City Hall, about drug-dealing and corruption.

Touch (1996), starring Christopher Walken and Bridget

Fonda, was directed and adapted by Schrader from the novel

by Elmore Leonard. Perhaps Schrader’s most significant

adaptation in the 1990s was Affliction (1997), adapted from a

novel by Russell Banks and starring

NICK NOLTE

,

JAMES

COBURN

, and

SISSY SPACEK

. Affliction was nominated for

SCHRADER, PAUL

363

multiple awards, including Best Screenplay, Best Actor

(Nolte), and Best Supporting Actor (Coburn, who won).

Schrader was also nominated for an Independent Spirit

Award for his work on this film.

In 1999, Schrader was reunited with director Martin

Scorsese in the adaptation of Joe Connelly’s novel, Bringing

Out the Dead, starring

NICOLAS CAGE

as an ambulance driver

who is existentially tormented because his patients keep

dying. Cage said of his character, “I came to realize that my

work [in the film] was less about saving lives than about bear-

ing witness. I was a grief mop.” That is exactly the kind of

character Schrader was born to adapt.

In 2002, Schrader directed Auto Focus, the story of mur-

dered television star Bob Crane of Hogan’s Heroes. True to

form, Schrader has always been something of a moralist, fas-

cinated by characters who are led into temptation. He sees

the world as a uniquely seductive place.

Schwarzenegger, Arnold (1947– ) A former world-

champion bodybuilder who became the most consistently

popular action star of the 1980s. Unlike

SYLVESTER STAL

-

LONE

, his closest competitor in both body mass and acting

style, Schwarzenegger has starred in tightly made lower-

budget movies that have been remarkably reliable money-

makers. In his rise to stardom, he overcame such obstacles as

an impossibly long last name, a thick Austrian accent, and a

gap-toothed appearance. He attained his goal thanks to pub-

lic fascination with his massively muscled body, his undeniable

star presence, and his savvy in recognizing his weaknesses and

picking his projects accordingly.

Born the son of a policeman in a small Austrian village,

Schwarzenegger began to lift weights as a form of training

for soccer and swimming. By the age of 15, however, he had

become seriously involved in what was then the fringe sport

of bodybuilding. At the age of 18, he won his first title,

Junior Mr. Europe. He would go on to win a great many

other titles including Mr. Olympia. In fact, by the time he

appeared as the focus of the highly regarded documentary

Pumping Iron (1977), he had been world champion for eight

consecutive years.

Schwarzenegger arrived in the United States at 21 to

continue his pursuit of bodybuilding fame. To make a living,

he formed a construction company in Los Angeles called

Pumping Bricks. Later, when he became a modestly well-

known name outside of the bodybuilding world due to the

success of Pumping Iron, Schwarzenegger decided to become

an actor. The consensus of many at the time was that the

good reviews Schwarzenegger received while playing himself

in Pumping Iron had gone to his head. His effort to break into

the movie business was considered a joke.

Five years later, however, Schwarzenegger was cast in the

perfect vehicle, playing the title character in John Milius’s

Conan the Barbarian (1982). He had just a few lines of dia-

logue, but he was the center of the film, showing off his mag-

nificent torso in a lively, if violent, sword-and-sorcery action

film. The critics might have sneered, but Conan and its

sequel, Conan the Destroyer (1984), grossed a combined total

of $100 million. Schwarzenegger was fast becoming a force

with whom to be reckoned.

The turning point in Schwarzenegger’s acting career came

with his mesmerizing villain’s role in The Terminator (1984). It

was a sleeper hit made on a low budget; the key factor in

Schwarzenegger’s favor was that he held the screen without

taking off most of his clothes and rippling his muscles.

Red Sonja (1985) was a modest disappointment—mostly

due to the poor acting by the two female stars, Brigitte

Nielsen and Sandahl Bergman (both of whom made

Schwarzenegger look like Laurence Olivier). But that one

film aside, Schwarzenegger’s movies have been box-office

winners. His ability to be likable despite his imposing bulk

has made him a film favorite of a great many male moviego-

ers. With a string of hits that includes Commando (1985), Raw

Deal (1986), Running Man (1987), Predator (1987), and Red

Heat (1988), his films took in more than $500 million in box-

office receipts. During the 1990s, Schwarzenegger continued

in the action sequels Terminator 2 (1991), which, of course,

then led to Terminator 3 (2003). In 1990, he starred in To t a l

Recall, a mind-bender based on Philip K. Dick’s We Can

Remember It for You Wholesale.

Although he has been associated primarily with action

films, he has also been successful with comedy. His physique,

accent, and mien are so incompatible with comic conventions

that the incongruity itself becomes comic. In a sense, he paro-

dies himself. Danny De Vito has been his best collaborator,

with the size disparity becoming comic, especially in Twins

(1988), where the two portray unlikely “twins.” Using the

same kind of improbability stretched to improbable limits, the

two appeared again in Junior (1994), in which the macho

Schwarzenegger becomes pregnant. In Kindergarten Cop

(1990), the title reflects the paradoxical and comic nature of

the situation, and in The Last Action Hero (1993) Schwarzeneg-

ger exhibits his comic talents as he participates in a spoof of the

action heroes he has played. In Batman and Robin (1997), he

was Mr. Freeze, a comic-book villain in one of the least suc-

cessful of the Batman films. For his efforts, he was nominated

for a Golden Raspberry award as Worst Supporting Actor.

But Schwarzenegger came back with End of Days (1999),

an apocalyptic thriller that did well at the box office but failed

to impress the critics. This was followed by The Sixth Day

(2000), another science-fiction thriller that recalled To t a l

Recall totally, advancing the star’s amusing potential for self-

deprecating deadpan drollery, as when his character says, “I

might be back.” He was back a year later in Collateral Dam-

age. Schwarzenegger starred in Terminator 3: Rise of the

Machines (2003).

Schwarzenegger, an active conservative Republican, mar-

ried a member of the liberal Democratic Kennedy clan in

1986, broadcast journalist Maria Shriver, and has political

ambitions—as proven by his victorious run for governor of

California in the state’s controversial 2003 recall election.

science fiction A genre that grew and matured rather

late by Hollywood standards. Although gangster films, musi-

cals, westerns, and so on all had at least their first blossom-

SCHWARZENEGGER, ARNOLD

364

ing as viable commercial categories by the 1930s, science fic-

tion features didn’t have their initial heyday until the 1950s,

and this despite the fact that George Méliès’s science-fiction

movie A Trip to the Moon (1902) was one of filmdom’s earli-

est sensations.

There was little in the way of films in the genre made

during the silent era in Hollywood. With technology racing

ahead during the first decades of the new century, it must

have seemed as if the future had already arrived. The present

was fascinating enough for the masses. Nonetheless,

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

tinkered with the genre in films such as The Flying

Torpedo (1916).

It wasn’t until

FRITZ LANG

’s classic Metropolis (1926), a

futuristic film about man’s loss of freedom in a technological

society, that science fiction appeared as a brand new subject

for the movies. Unfortunately, the elaborate models and spe-

cial effects required to make Metropolis nearly bankrupted

UFA (the German film company that produced Lang’s mas-

terpiece), and the movie was a beautiful and intelligent box-

office failure.

In England, the much admired Things to Come (1936),

directed by William Cameron Menzies with a script by H. G.

Wells, not only suggested a future that might come to pass

but was the precursor of the science-fiction films of the 1950s

and beyond. In the meantime, however, back in Hollywood,

the science-fiction film was born as a bastard child of the hor-

ror genre.

It was during the 1930s, when horror was at the height of

its popularity, that the mad-scientist film came into vogue,

spinning off a peculiar form of science-fiction film that found

its roots in Frankenstein (1931). The result was a hybrid hor-

ror/science-fiction film such as The Invisible Ray (1936), in

which the line: “There are some things man is not meant to

know,” was uttered for the very first time in the movies.

Knowledge of science was growing at a pace far beyond soci-

ety’s ability to digest it, and the backlash (in the form of dis-

trust of scientists) was apparent in movies such as Dr. X

(1932), which dealt with the creation of synthetic flesh; The

Island of Lost Souls (1932), in which a mad doctor tries to turn

animals into humans through vivisection; and The Invisible

Man (1933), concerning a scientist who tries to rule the world.

If horror movies present our personal primal fears, than

science fiction presents, like no other genre, the fears and

anxieties of society as a whole. The political, cultural, socio-

logical elements of science fiction are often visceral state-

ments of the hopes, fears, and values of our species.

The closest thing in the 1930s to what we generally call

modern science fiction could be found in the serials that fea-

tured Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, but these were sim-

plistic movies based on comic-strip characters and were made

for children.

Science-fiction films virtually disappeared during World

War II, but the advanced weapons of the conflict—princi-

pally, the V-2 rocket and the atomic bomb—eventually

unleashed both the imagination and the interest of a terrified

audience in a genre that suddenly seemed quite relevant.

In 1950, producer George Pal struck a commercial

mother lode when he made Destination Moon. This unex-

pected low-budget hit, based on a Robert Heinlein novel

called Rocket Ship Galileo, combined a good story and believ-

able special effects to rivet audiences to their seats. The film

won an Oscar for Best Special Effects; the science-fiction film

was finally on the map.

George Pal went on to produce several other science-fic-

tion classics during the next decade, including When Worlds

Collide (1951) and War of the Worlds (1953). The first golden

age of science fiction was under way when Pal’s films were

joined by

HOWARD HAWKS

’s The Thing (1951),

ROBERT

WISE

’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), and Jack Arnold’s

It Came from Outer Space (1953).

This initial wave of science fiction was generally made

with relatively unknown actors and with modest budgets. But

in 1956, MGM took a chance and put one of their better-

known (if aging) stars, Walter Pidgeon, in the serious and

intelligent Forbidden Planet. The movie, based on Shake-

speare’s The Tempest, introduced an entirely new sort of evil

creature: the Monster from the Id. At the same time,

DON

-

ALD SIEGEL

directed the classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers

(1956), a movie that was just as much a political attack on

right-wing American society as it was about pods from outer

space. Science fiction wasn’t just for kids anymore.

At their simplest level, movies such as Invasion of the Body

Snatchers spoke to humankind’s sense of wonder about the

stars. But in the 1950s, the answer to the question “Is there

life in outer space?” was a frightening “yes,” not only in the

Don Siegel film but also in movies such as The Twenty-

Seventh Day (1957), The Monolith Monsters (1957), and I Mar-

ried a Monster from Outer Space (1958).

As science fiction replaced horror in the 1950s, children

and teenagers lined up to see “B” movies that exploited their

unique fears of annihilation. The first generation to live

under the threat of the bomb spent the better part of the

1950s watching science-fiction films dealing with the issue of

science running amok on a global rather than an individual

level, as in 1930s movies. In film after film, such as The Beast

from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Attack of the Crab Monsters

(1957), and Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959), nuclear explo-

sions and scientific experiments caused either the resurrec-

tion or the creation of huge, deadly creatures that threatened

to destroy humanity. (Movies about monsters either created

or unleashed by science fall for our purposes within the sci-

ence-fiction category. Films about dinosaurs and other simi-

lar creatures are categorized as monster movies.)

With the advent of the so-called missile gap during the

1960 presidential campaign and the subsequent Cuban Mis-

sile Crisis, science-fiction films reflected more pointed fears

of outright nuclear devastation in movies such as The Last

Woman on Earth (1960), Panic in the Year Zero (1962), and The

Day the Earth Caught Fire (1962).

With the easing of the fear of nuclear extermination, sci-

ence fiction turned in the latter half of the 1960s to explore a

broader range of ideas. For instance, Fantastic Voyage (1966)

was a journey through the human body, while Planet of the

Apes (1968) was a moralistic parable about human behavior.

It was

STANLEY KUBRICK

’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968),

however, that changed the face of science fiction forever,

SCIENCE FICTION

365

turning what had heretofore been a fringe genre into a

mainstream mainstay due to a combination of special effects

and intellectual appeal. It enjoyed a spectacular success at

the box office.

Science-fiction films were made rather consistently dur-

ing the decade after 2001. Movies such as The Andromeda

Strain (1971) and Silent Running (1972) achieved a very high

level of artistic success, but they didn’t truly catch fire at the

box office.

It wasn’t until

GEORGE LUCAS

made

STAR WARS

(1977)

that the promise of 2001 was realized, with a rousing adven-

ture yarn, spectacular special effects, and a simple, yet ele-

gant, mysticism (“May the force be with you”) that appealed

to kids of all ages. Star Wars was an unabashed salute to Buck

Rogers and Flash Gordon but was made with such lavish

detail, love, and cinematic flair that it became one of the most

commercially successful movies of all time.

Star Wars was such a huge hit that it ushered in a second

golden age of science fiction. In its wake, Lucas produced

two more Star Wars epics; a continuing series of Star Trek

movies spawned from a TV series made hundreds of millions

of dollars; and

STEVEN SPIELBERG

followed with two of his

most beloved films, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

and E.T.—The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). These latter two films

are of particular significance because they presented aliens

not as enemies, as was so often the case in the science-fiction

films of the 1950s, but as friendly, benign creatures. These

films offered a comforting, less paranoid view of the cosmos.

It’s been postulated that science fiction has replaced the

western as the genre of choice for those interested in movies

about the frontier, and that is certainly true; one need only

watch Outland (1981), an obvious remake of High Noon, to see

how science fiction has subsumed a great many of the west-

ern concerns. But science fiction, in more recent years, has

incorporated the police procedural genre as well, in films

such as Blade Runner (1982) and Robocop (1987).

During the 1990s, science fiction continued to concen-

trate on dystopian futures and revealed a continuing fascina-

tion with cyborgs, replicants, mad science, time travel, alien

invasions, and end-of-the-world scenarios. Perhaps the most

spectacular example of mad science run amok was Steven

Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993), starring Sam Neill, Laura

Dern, Jeff Goldblum, and Sir Richard Attenborough, who

intends to clone dinosaurs for his Jurassic theme park on an

isolated island, throwing nature disastrously out of balance.

The film, which one critic called the Jaws of the 1990s, was

so successful that it spawned two sequels.

Spielberg worked the genre again when he took over the

Stanley Kubrick project A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001) after

Kubrick’s death. Haley Joel Osment starred as a robot who,

like Pinocchio, just wants to be a real boy. Oddly designed

and executed and hardly a feel-good movie, A.I. still grossed

more than $78 million. In 1990, Irvin Kershner brought back

Peter Weller’s RoboCop in the sequel RoboCop 2, which was

even more dark and violent than Paul Verhoeven’s original

version (1987). In RoboCop 3 (1991), the series was set in

Japan. Cultural adjustments were made, creating an android

ninja as Robo’s adviser. In Roland Emmerich’s Universal Sol-

dier (1992), Jean-Claude Van Damme, playing a soldier killed

in Vietnam, is brought back to life to fight again as a “per-

fect” soldier.

Jean-Claude Van Damme also starred in the Peter Hyams

time-travel film Timecop (1994), which echoed the

ARNOLD

SCHWARZENEGGER

Terminator series but didn’t quite match

it (though the film made more than $44 million). James

Cameron directed Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), bring-

ing back stars Linda Hamilton and, of course, Arnold

Schwarzenegger to warn audiences about the dangers of the

future. Critic Jay Telotte describes such films as postmodern

science fiction. The term would also describe Paul Verho-

even’s Total Recall (1990), another Schwarzenegger vehicle

adapted from Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Remember It for You

Wholesale,” and Luc Besson’s bizarre and futuristic The Fifth

Element (1997), starring

BRUCE WILLIS

and Gary Oldman.

Gattaca (1997) starred Ethan Hawke intent on self-improve-

ment in a future dystopia where genetic tinkering enables

parents to create perfect children for a perfect world.

Other films mingled dystopian futures with paranoid par-

allel-universe fantasies, such as Dark City (1998), starring

Kiefer Sutherland. This film’s interesting premise was further

advanced by directors Andy and Larry Wachowski in The

Matrix (1999), a huge hit starring Keanu Reeves as Neo, the

quester, and Laurence Fishburne as his mentor, Morpheus,

who awakens Neo to the notion that life is but a dream.

Matrix set the bar higher for science fiction in the late 1990s

and made an impressive $190 million. By the summer of

2003, The Matrix Reloaded was cleaning up in theaters nation-

wide. Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly called it “an

insanely pretentious and dazzling cyberaction sequel,”

describing it as “physics gone majestically stoned.”

Yet not all science fiction of the 1990s was so bizarre and

extravagant. George Lucas completed his “prequel,” Star

Wars: Episode 1—The Phantom Menace (1999), starring Liam

Neeson, Ewan McGregor, and Natalie Portman, offering a

more mature approach than the earlier Star Wars movies

could have done. This “swashbuckling, extragalactic get-

away” (in the words of Janet Maslin) grossed $430 million,

proving that the genre was still potent. Another, more con-

ventional variant of the alien invasion subgenre, Paul Verho-

even’s Starship Troopers (1997), was adapted from Robert A.

Heinlein’s 1959 novel of the same title. Critics branded the

film fascist and were repulsed by its extreme violence.

Far more mundane were two end-of-the-world fantasies:

Michael Bay’s Armageddon (1998), which was influenced by

producer Jerry Bruckheimer, put the Earth in jeopardy when

an asteroid was discovered on a collision course; Mimi

Leder’s Deep Impact (1998) was developed along the same

lines. Bay’s film had all the special effects and was a really big

boom and doom spectacle, but Leder’s more modestly bud-

geted effort was done with a far more human touch and a bet-

ter cast, featuring Robert Duvall, Vanessa Redgrave,

Maximilian Schell, and, most impressively, Morgan Freeman

as the president of the United States, who assured the coun-

try: “Life will go on; we will prevail.” Armageddon made more

than $200 million, and Deep Impact topped $140 million.

Recent science fiction movies have included a spate of block-

SCIENCE FICTION

366

busters, bombs, and remakes. Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes

(2001) was an abysmal updating of the classic. The low-pro-

file but effective Impostor (2002) and the big-budget mish-

mash Minority Report (2002) proved that the work of author

Philip K. Dick was still ripe for adaptation. Steven Soder-

bergh’s Solaris (2002) offered a different vision of the old sci-

ence-fiction novel than did the original Russian adaptation.

Also in a year for sequels, 2003, The Matrix: Reloaded, The

Matrix: Revolutions, and Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines all

testified to the proven appeal of the genre.

score The music written to accompany a motion picture.

Music was part of the moviegoing experience long before the

advent of sound films. When one- and two-reelers were first

shown in vaudeville houses, the orchestras that played for the

various acts also played background music for the movies. A

short time later, when movie houses began to dot the Amer-

ican landscape, the musical tradition continued; piano players

were hired to supply generic romantic music, chase music,

and so on.

The breakthrough in the scoring of American films came,

as did so many early cinematic innovations, from

D

.

W

.

GRIF

-

FITH

. He prepared a specific film score for a full orchestra for

The Birth of a Nation (1915). The power of that score, which

was mostly adapted from previously existing music, so

enhanced the picture that many subsequent feature-length

films followed the master’s lead. But whether full orchestras

in the big cities played music written specifically for each

scene of a film or piano players in small rural towns played

the main themes of a film’s score, there was music in abun-

dance during the silent era.

Ironically, the talkies proved to be a hindrance to musical

scores, at least in the late 1920s and very early 1930s. Early

sound technology was such that getting the words on film

was hard enough without worrying about music as well. Only

unobtrusive musical accompaniment could be heard in the

background of most comedies and dramas during those diffi-

cult transitional years.

By the mid-1930s, however, the technology had advanced

enough to allow significant musical scores to be added to

most motion pictures. Although many were often adaptations

of existing melodies, the art of composing original music for

the screen was coming into full flower, thanks to such com-

posers as Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold.

There have been three separate Academy Award cate-

gories for scoring: Best Original Music for a Drama or Com-

edy, Best Music Adaptation for a Drama or Comedy, and Best

Scoring for a Musical. In recent years, the latter category has

been dropped due to the paucity of musical films.

The importance of “mood” music in films cannot be

taken lightly. The scores of such films as Gone with the Wind

(1939), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), The Pink Pan-

ther (1964),

THE GODFATHER

(1972), The Sting (1973), Jaws

(1975), and

STAR WARS

(1977) all attest to the power of music

to affect the audience in the most fundamental ways.

See also

COMPOSER

;

HERRMANN

,

BERNARD

;

MANCINI

,

HENRY

;

STEINER

,

MAX

;

TIOMKIN

,

DIMITRI

;

WILLIAMS

,

JOHN

.

Scorsese, Martin (1942– ) One of the first—as well

as one of the most creative and adventurous—of a new breed

of film-school-trained directors who came to prominence in

the late 1960s and early 1970s. Scorsese has a reputation for

making films about violent people who live on the fringe of

society, but his themes run deeper: His heroes are desperate

for redemption. Religion rarely helps them, and they channel

their violent temperaments in directions that point to deep

flaws in our culture.

Scorsese, a sickly child growing up in New York’s Little

Italy, found a refuge in the movies. He had intended to

become a priest but found his true calling to be the screen

rather than the cloth. He went to New York University and

received his undergraduate degree in film communications in

1964, following it up with an M.A. in the same subject from

New York University in 1966. While still a student, he made

a number of prize-winning films, among them What’s a Nice

Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (1963), It’s Not Just

Yo u (1964), and The Big Shave (1967).

His knowledge and skill as a filmmaker were fully appre-

ciated at New York University, where he found employment

as an instructor. While teaching at his alma mater, Scorsese

made his first full-length film, Who’s That Knocking at My

Door? (1968), a personal film that presaged his breakout

movie, Mean Streets (1973). Between those two films, how-

ever, Scorsese continued to learn his craft by working as an

editor on the famed rock-concert movie Woodstock (1970) and

directing a

ROGER CORMAN

quickie, Boxcar Bertha (1972).

Hollywood took notice of the intense young director

when his autobiographical film Mean Streets was shown at

the 1973 New York Film Festival. Made on a shoestring

budget in Little Italy, the movie not only launched Scors-

ese’s directorial career, but it also brought actors

HARVEY

KEITEL

and

ROBERT DE NIRO

to the public’s attention.

Scorsese used both actors extensively in his later films, par-

ticularly De Niro.

Mean Streets was a critical success but not a box-office

winner. His next two films, however, Alice Doesn’t Live Here

Anymore (1975) and Taxi Driver (1976), were huge hits. The

former movie struck a nerve as one of the first popular films

concerning a woman’s struggle to survive financially and

emotionally in modern society without a man. After the vio-

lence of Mean Streets, it seemed an unlikely project for Scors-

ese, but survival has often been the theme of many of the

director’s films. Laced with comedy, Alice Doesn’t Live Here

Anymore was eventually adapted into the TV sitcom Alice.

Taxi Driver was undoubtedly the most controversial film

of the 1970s. This dark portrait of a loner driven toward vio-

lence was a riveting tour de force of writing (Paul Schrader),

acting (Robert De Niro in the title role), and especially

directing. Scorsese’s affinity for outsiders was never more

vividly revealed than in this film. Although the child prosti-

tute, played by

JODIE FOSTER

, and the bloodbath finale out-

raged some segments of society, no one questioned the power

of Scorsese’s filmmaking. In short order, Scorsese had arrived

as one of America’s premier young directors.

His willingness to experiment was in evidence when he

tried to bring back the lavish movie musical with New York,

SCORSESE, MARTIN

367