Russell I. (ed.) Whisky. Technology, Production and Marketing

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 138 114-151

that although active yeast growth ceases at about 24 hours, fermentation of

sugars continues (although at a slower rate); therefore there is a continuing

increase in alcohol content and a corresponding fall in specific gravity.

However, with the end of active yeast growth there is no further uptake of

a-amino nitrogen from the wort or increase in temperature. In fact, the amount

of a-amino nitrogen normally increases in the wash in the later stages of

fermentation due to autolysis of a proportion of the yeast, and the temperature

may fall slightly without continuing yeast metabolism.

Metabolic activity generates heat. In a brewery, fermentation temperature is

carefully controlled to within 0.58C of the selected temperature by attemper-

ated panels in the walls of the fermentation vessels. In most distilleries there is

no attempt at temperature control other than adjusting the temperature of the

wort entering the washback according to ambient temperature. In cold

weather wort could be adjusted to, say, 228C, but in warmer weather to

198C, so that the natural increase in temperature would result in both fermen-

tations reaching 33–348C. Other reasons for reducing the setting temperature

are a higher than normal original gravity of the wort (within a range that could

be expected to accelerate the fermentation) or a lower ratio of brewing : distil-

ling yeast. With stainless steel washbacks a simple temperature control may be

used: in some distilleries by spraying the outside of the vessels with cold

water, in other cases the fermenting wash may be circulated through an exter-

nal cooler. In theory the latter system could also be used with wooden vessels,

but it is not known whether this has been tried. Commercial distilling yeast

strains ferment well at up to about 34–358C, but at higher temperatures meta-

bolic activity rapidly declines. Yeast purchased from ale breweries is also

capable of growth at up to 33–348C, but this is too high for lager yeast,

which typically has a maximum growth temperature of 28–30 8C (Walsh and

Martin, 1978). Therefore if lager yeast is used as part of the inoculum it assists

the distilling yeast only in the early part of the fermentation, but of course the

structural components of the yeast are still available to contribute to congener

development during distill ation.

So the special conditions of a distillery fermentation result in an important

difference from the textbook version of the microbial growth curve. While the

growth of micro-organisms at constant temperature can be expressed as a

straight line by plotting cell numbers logarithmically against actual time

(hence the term log phase), that is not true in Scotch whisky fermentations.

Heat generated by yeast metabolism causes the temperature to rise throughout

most of the log phase, and growth rate increases accordingly.

Another important difference from the superficially similar brewery fer-

mentation is the lac k of heat treatment of the wort corresponding to the

hop-boiling stage of brewing, which inactivates malt enzymes. Malt distillery

mashing uses a succession of increasing temperatures (see Chapte r 2), but the

‘first water’ is tradi tionally at about 648C, the precise temperature varying

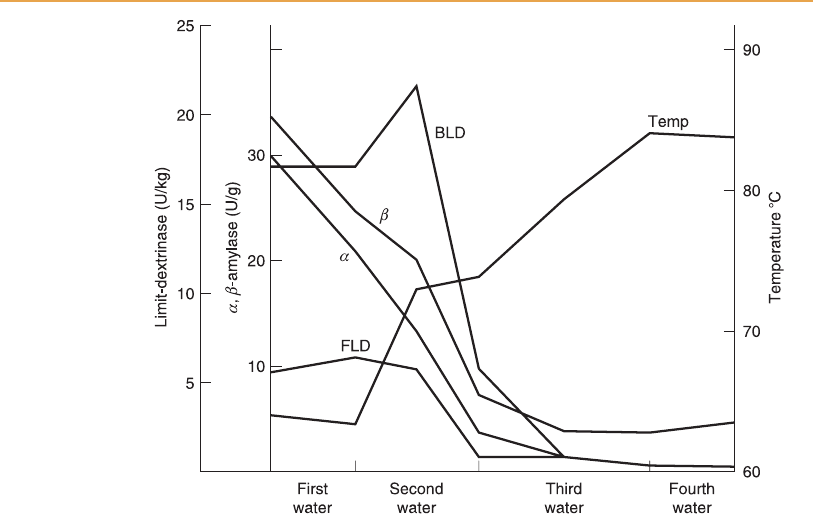

according to distillery. At the end of mashing at that temperature Walker et

al. (2001) measured (in that first batch of wort co oled to 208C and collected in

the washback)? a- and b-amylase levels at about 80 per cent of those in the

original malt, and free limit-dextrinase was slightly increased (Figure 4.13).

138 Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 139 114-151

Appreciable activity of the amylases and bound limit-dextrinase remained

even after mashing with the ‘second water’ of higher temperature. Since

grain distillery mashing is at a fixed temperature of about 63–648C, again

appreciable hydrolytic activity persists to fermentation. Therefore in both

grain and malt distilleries a high proportion of the cereal starch is converted

to fermentable sugars and then to alcohol by continuing hydrolysis during

fermentation.

Since the amount of pitching yeast for distillery fermentations is normally

measured as cell dry weight, it is important to know the water content of the

compressed, cream or dried yeast supp lied. Experience has shown that a

minimum of 18 kg dry weight of distilling yeast is required per tonne of

malt in malt distilleries, with equivalent addition in grain distilleries.

Lower pitching rates reduce spirit yield, probably because there is more

yeast growth and therefore more sugar is converted to cell mass rather

than ethanol. Also the pitching rate must be increased slightly for mixtures

of brewing and distilling yeast, to at least 22 kg/t with 50 per cent of brew-

ery yeast. In terms of cell count, 1.8 per cent of the weight of malt corre-

sponds to 3–4 10

7

cells/ml, depending on the origin al gravity of the wort.

Alternatively, the pitching rate can be expressed as 5 g pressed yeast per litre

of wort (Bathgate, 1989).

Chapter 4 Yeast and fermentation 139

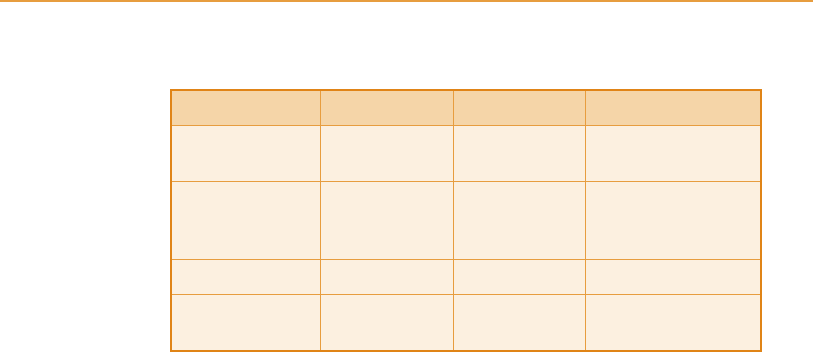

Figure 4.13

Activity of amylolytic enzymes during dist illery mashing (Walker et al., 2001).

a, a-amylase, b, b-amylase, BLD, bound limit-dextrinase, FLD, free limit-dextrinase.

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 140 114-151

For about six hours after inoculation the cell count remains constant, hence

the term lag phase – a relic of the earlier belief that little activity took place. In

reality the lag phase is a period of intense biochemical activity as the yeast

cells adjust from their previous conditions of culture to the conditions in fresh

wort. The change is particularly severe for brewing yeasts, transferred from an

anaerobic alcoholic low-nutrient environment at the end of fermentation, via a

period of transport and storage under moderately inhibitory conditions, to the

nutrient-rich aerobic alcohol-free wort. It is possible that som e yeast growth

does take place during the lag phase, but is balanced by the death of a propor-

tion of cells by the osmotic shock of transfer to the high sugar concentrat ion of

fresh wort so the cell count remains approximately constant.

By six hours after pitching, and perhaps earlier if only distilling yeast is

used, growth begins in the sense of increasing cell numbers – the stage var-

iously known as growth, logarithmic or log phase. In a brewery, only about

eight- to ten-fold multiplication is possible, i.e. three cell generations, and

possibly a fourth generation by a small proportion of cells. Further growth

is impossible because of the lack of the essential membrane components unsa-

turated fatty acids and sterols, which cannot be synthesized under the anae-

robic conditions of fermentation. Distillery yeast, unlike brewery yeast

recovered from the previous fermentation, was originally grown under vigor-

ous aerobic conditions, generating an excess of these essential lipids, and if

added to well-aerated wort could grow up to twenty-fold (i.e. slightly over

four generations). With the typical temperature profile of a distillery fermen-

tation the log phase would be expected to last for 18–24 hours, but ultimately

there is no further increase in yeast population and the culture enters the

stationary phase (i.e. stationary with respect to the number of viable yeast

cells). The lack of membrane lipids is an important factor ending yeast growth

in a distillery fermentation, but metabolic activity continues for a further 12–24

hours, althou gh at a slower rate. There may be some slight continuing growth

of the yeast, but this is balanced by death and autolysis of a proportion of the

cells so the viable population remains constant. It is reasonable to assume that

the theoretical assessment by Werner-Washburne et al. (1993) is applicable to

the stationary phase of Scotch whisky fermentations. Ultimately, yeast growth

ceases and the increasing rates of cell death and auto lysis initiate the decline

phase, but this is happens only near the end of the 48-hour timescale of the

majority of distillery fermentations.

A figure of 0.131 (or 0.1315) is in common use for estimating the alcohol

yield of a distillery fermentation – for example, wort of original gravity 10578

fermented to 9978 contains (1057 997) 0.131 ¼ 7.86 per cent alcohol by

volume. This conversion factor is higher than its equivalent value 0.129 in

the brewing industry to take account of the more efficient ferm entation of

unboiled wort.

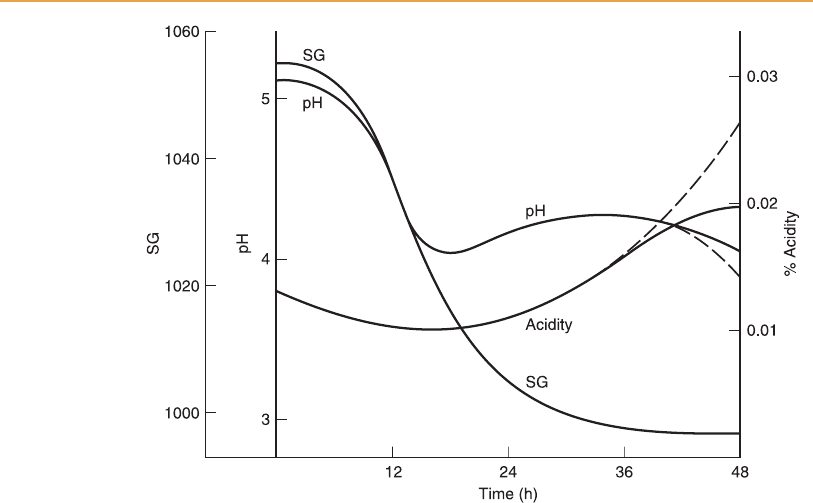

During fermentation hydrogen ions are excreted by the yeast, resulting in a

fall in pH. Figure 4.14 shows the typical trend in fermentation of an all-malt

wort by a pure culture of distiller’s yeast, initially pH 5.4, falling to a lowest

value of 4.0–4.1 (Dolan, 1976) and increasing slightly during the stationary

phase by the release of amino acids from autolysing yeast cells. Perhaps auto-

140 Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 141 114-151

lysis of part of the batch of brewer’s yeast accounts for the slightly but

consistently higher pH values throughout mixed-yeast fermentations.

However, in the case of fermentations showing late growth of lactic bacteria,

which use yeast autolysate as nutrient, the pH can fall again to about 3.8.

Growth of lactic bacteria during the stationary phase, on residual dextrins

and pentoses that are non-fermentable by the yeast, and trehalose and nitro-

genous products of yeast autolysis, is generally considered to make a valu-

able contribution to the range of flavour congeners in the wash and

ultimately in the final whisky (Geddes, 1985; Barbour and Priest, 1988). On

the other hand, contamination early in the fermentation is undesirable,

reducing the spirit yield by loss of ferm entable sugars to the metabolism

of lactic bacteria (Dolan, 1976).

The changes in pH affect the activity of a- and b-amylases and limit-dex-

trinase, and therefore the hydrolysis of polysaccharide during fermentation.

Starch and dextrins remaining after mashing are hydrolysed most rapidly in

the lag phase, but as fermentation begins and pH falls the hydrolytic activity

of malt enzymes declines. Although Watson (1983) quoted inactivation of

Chapter 4 Yeast and fermentation 141

Figure 4.14

Variation in pH during a malt distillery fermentation (modified from Dolan, 1976).

Broken lines after 36 hours show the effect of contamination by lactic bacteria; solid

lines show the normal progress of fermentation. The initial pH in a grain distillery is

higher than shown here. Wheat or barley typically give pH 5.5–5.7 and maize pH

5.7–6.0 at the start of fermentation, but otherwise the graphs are equally applicable

to grain distillery fermentations.

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 142 114-151

a-amylase at about pH 4.9, many distillers believe that amylolytic activity

continues (at a decreasing rate) to lower pH values, ultimately ceasing at

about pH 4.4. Under-modified malts are especially dependent on continuing

conversion during fermentation, so the higher pH (by approximately 0.2 units)

throughout fermentations that inclu de brewer’s yeast is advantageous for

amylolysis. However, in addition to the competition for carbohydrate referred

to above, the lower pH associated with heavy early contamination by lactic

bacteria may also reduce spirit yield.

Vigorous fermentation also causes foaming, which is normally controlled by

a rotating ‘switcher’ blade in the head space of the washback. Some brewing

yeast strains are more liable than others to cause froth or head during a

brewery fermentation and, despite the moderating effect of the large propor-

tion of distilling yeast, they inevitably maintain that characteristic in a wash-

back. It has also been suspected that some barley varieties are associated with

unusually frothy fermentations (and wash distillations). Although wheat has

become the predominant cereal for grain distilleries in recent years, one of the

advantages of maize is its high oil content, which has a valuable natural anti-

foam effect during ferm entation. However, since additives are not permitted

by the Scotch Whisky Regulations, the deliberate addition of antifoam to a

distillery fermentation is not possible.

Brewers rely on flocculence of yeast to achieve a partial clarification of beer

at the end of fermentation. Flocculation , the spontaneous aggregation of cells

into clumps, which settle more readily by their increased mass (Stratford,

1992), is unacceptable in distilling yeast. Flocculated yeast cells settling on

heating surfaces of the wash still will char, causing flavour defects in the spirit

and restricting heat transfer, so it is essential to maintain a uniform yeast

suspension throughout fermentation and wash (or continuous) distillation.

Although lager yeast is either non- or poorly flocculent and therefore not a

problem in this regard, distillers purchasing ale yeasts must beware of

strongly flocculent strains.

In this section the duration of fermentation has been assumed to be 40–48

hours, which is certainly true of grain distilleries. However, even if a malt

whisky fermentation appears complete by 40 hours, Geddes (1985) advised

against distillation of the wash before 48 hours to allow development of fla-

vour by lactic bacteria. Also, 48-hour fermentations are convenient for round-

the-clock operation of a small traditional malt whisky distillery with mashing

at eight-hour intervals. However, a few malt distilleries operate longer fer-

mentations to encourage late lactic contamination of the fermentation, but

therefore require more fermentation capacity to maintain energy-efficient

rapid re-use of the wash still.

Production of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide and ethanol have similar molecular weights, and therefore are

produced in approximately equal amounts during fermentation. Although

carbon dioxide is not collected in malt distilleries on the same large scale as

142 Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 143 114-151

in grain whisky distilleries, there may be some commercial value in collecting

the gas as a co-product.

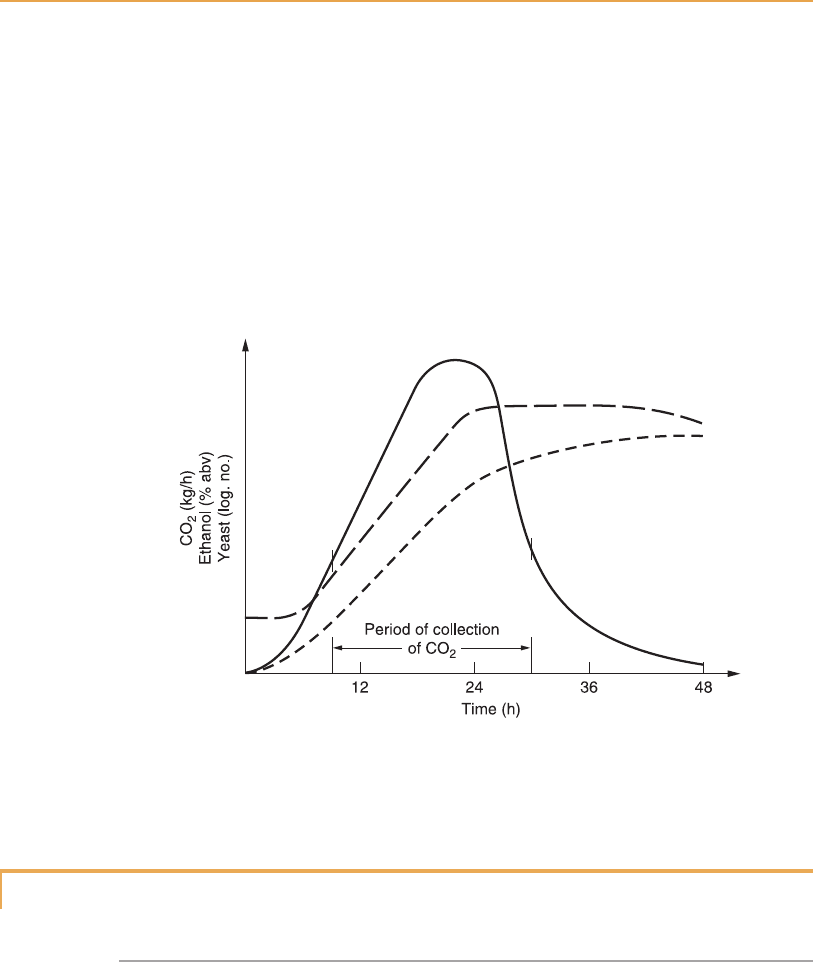

Although carbon dioxide evolution begins towards the end of the lag phase,

the first of the gas is contaminated by the head-space air that it flushes from

the washback. The most rapid evolution occurs during the log phase, subse-

quently subsiding during the stationary phase to a rate where it is unecono-

mical to collect it. Therefore although approximately half of the weight of

sugar fermented is released as carbon dioxide, only about half of that amount

is actually available for collection between about the tenth and thirtieth hours

of fermentation. Figure 4.15 shows the general trend of production (measured

in kg/h) during fermentation, but because of wide variation between distil-

leries actual values are not quoted.

Contamination

Possible contaminants of distillery fermentations

Microbial contamination of the fermentation is potentially another source of

desirable flavours in the final whisky, although the effect could equally well be

an off-flavour. The principal sources of the unavoidable contaminants of dis-

tillery fermentations (Table 4.5) are the microbial flora of the malt (acetic and

lactic bacteria and aerobic yeasts), residual contamination of wooden wash-

backs (potentiall y by all organisms on the list) and the yeast itself (different in

brewery or distillery yeast, see later).

Chapter 4 Yeast and fermentation 143

Figure 4.15

Evolution of CO

2

during fermentation. Solid line, CO

2;

broken line, ethanol; circle/

broken line, yeast log no.

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 144 114-151

Since the wort is not boiled, some microbial contami nation of the wash is

inevitable. The initial temperature of mashing in a malt whisky distillery is

insufficient to sterilize the wort, although a temperature of 63–658C will cer-

tainly cause a substantial reduction in the number of potential spoilage organ-

isms (Geddes, 1985). In grain distilleries the cereal is sterilized by pressure

cooking, but since the malt slurry is heated only to about 638C, and then

briefly, malt is a potential source of contamination, especially since with little

kilning (or none at all) the microbial flora developing during germination is

not destroyed. However, at approximately 10 per cent of the cereal raw mate-

rial, the potentially contaminating effect of malt is proportionally less than in a

malt distillery.

Wort itself has little anti-microbial effect other than the osm otic stress of

the sugar concentration, but once fermentation is under way the wash is

protected by the synergistic combination of various anti-microbial effects:

the low pH, anaerobic conditions, dissolved carbon dioxide and the exhaus-

tion of fermentable sugars by the end of fermentation. These factors were

identified by Hammond et al. (1999) as protective effects in breweries, but are

equally appli cable to distillery fermentations. For example, Dolan (1976)

encountered unidentified Gram-positive cocci in wort, which quickly died

off at the start of fermentation. Only a limited range of spoilage micro-

organisms produce unacceptable flavour congeners that could distil into

the new spirit, but it is also possible that a serious level of contamination,

competing with the culture yeast for fermentable sugar, could reduce spirit

yield (Dolan, 1979).

Aerobic yeasts grow well in the culture conditions of the yeast factory,

where even a low level of accidental contamination can rise to significant

144 Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing

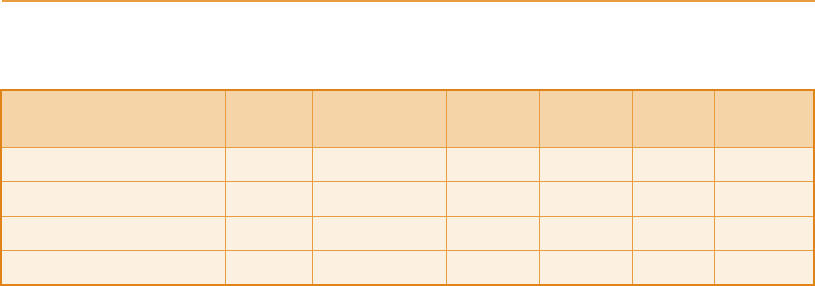

Table 4.5

Possible microbial contaminants of distillery fermentations

Aerobic

yeasts

Fermentative

yeasts

Lactic

bacteria

Acetic

bacteria

Zymo-

monas

Entero-

bacteria

Brewery yeast þþ þ þ þþ

Distillery yeast þ þ þ

Wort, early fermentation þþ þ þ þ

Late fermentation, wash þ þ þ

Effect of contamination: approximate loss of spirit yield in a malt distillery due to growth of Lactobacillus from the

start of fermentation (Dolan, 1976; Barbour and Priest, 1988):

Up to10

6

/ml < 1% loss

1^10 10

6

/ml 1^3% loss

1^10 10

7

/ml 3^5% loss

Above 10

8

/ml > 5% loss

There is no loss of spirit yield when Lactillobacillus grow only at the end of fermentation, on nutrients from

autolysed yeast.

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 145 114-151

numbers in the final prod uct. Fortunately such contaminants can grow only

in the first few hours of the distillery fermentation (Campbell, 1996b), but

some, especially Pichia spp., produce in that time sufficiently high levels of

esters to affect the congener profile of the wash and, more probably in malt

distilleries, of the spirit. Fermentative yeast contaminants are more likely to

be associated with brewery yeast. Although they can be a serious problem in

breweries, with their similar metabolism to S. cerevisiae they are unlikely to

cause flavour problems in a distillery. The bacteria producing acetic and

lactic acids may be present on malt, and Geddes (1985) reported introduction

of both into the fermentation from that source. Since acetic bacteria are strict

aerobes they are less of a problem than the lactic bacteria, especially lacto-

bacillus, which can grow throughout the fermentation. Although written

primarily for brewery microbiologists, the review by Priest (1996) also

includes distillery lactobacilli. Enterobacteria are unlikely contaminants, but

may be introduced if contaminated water is used for rinsing sterilized equip-

ment. However, that group also includes Obesumbacterium, which is a pos-

sible contaminant of brewery yeast. Fortunately these bacteria are quickly

inactivated by the falling pH and increasing alcohol content during fermen-

tation. They are a more serious problem in breweries, since they increase

over successive fermentations with re-use of contaminated yeast, but that is

irrelevant to Scotch whisky distilleries: yeast is never re-pitched to a follow -

ing fermentation. The Gram-negative bacteria that disappeared within ten

hours of pitching the fermentations studied by Dolan (1976) could well

have been either acetic bacteria or enterobacteria.

Manufacturers of distillery yeast do not guarantee a pure culture (R. C.

Jones, 1998), but in practice the likely level of contamination is low. Brewery

yeast, on the other hand, is a potential source of both fermentative yeasts and

bacteria that are able to grow sufficiently during distillery fermentations to

produce detectable amounts of flavour congeners. If obtained from an unreli-

able source, brewery yeast could be contaminated by lactobacilli, pediococci

and Zymomonas, all of which produce congeners that distil with the spirit

fraction and compete with the culture yeast for fermentable sugars to reduce

the spirit yield (Dolan, 1976, 1979). Inhibition of yeast growth by some strain s

of acetic and lactic bacteria (Thomas et al., 2001) is also a possibility, although

in practice the developing anaerobic conditions and excess of culture yeast

suppress the antibiotic effect of acetic bacteria. In an interesting incidental

observation Barbour and Pr iest (1988) noted that different strains of lactobacilli

varied in their effects: even if the amount of their growth was approximately

equal, some strains caused a substantial loss of spirit yield while in other

contaminated fermentations different strains had no such effect.

Ineffective sterilization of washbacks and associated equipment, or contami-

nated rinse water, are other possible sources of contamination, but are largely

avoidable with correct procedures. Stainless steel washbacks cleaned after

each fermentation and sterilized either by steam or by the final stage of a

CIP system are less likely to be a source of contamination than wooden wash-

backs, which are almost impossible to sterilize (Dolan, 1976). However, even

though some microbial contaminants in the cracks will survive any practical

Chapter 4 Yeast and fermentation 145

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 146 114-151

duration of steaming, cleaning and steaming between fermentations prevent

the inevitable low level of contamination building up to dangerous levels.

Table 4.5 shows the possible types of contaminant. For different reasons,

aerobic (oxidative) yeasts, acetic bacteria and enterobacteria are able to

grow only in the early stages of fermentation. The development of anaero-

bic conditions inhibits the first two groups. Enterob acteria, although unaf-

fected by anaerobiosis, are inhibited by the falling pH and increasing

alcohol content. Although lactobacillus contaminants are the most likely

bacteria from malt, Pediococcus spp. are also possible, and some strains

produce an extracellular polysaccharide that causes ropiness in beer or

wash (Priest, 1996) and can be genuinely troublesome. Fermentative yeast

contaminants, like brewery and distillery culture yeasts, form ethanol and

carbon dioxide and, usually, the same flavour metabolites, although these

congeners are almost certainly be produced in differen t amounts. Although

the resulting off-flavour is an important nuisance effect in breweries, dis-

tillation normally eliminates this problem. Even if a particular batch of low

wines has a higher than normal level of flavour congeners, and some wild

yeasts of the genus Pichia are notorious for high ester production, that

effect can be diluted by mixing with feints derived from an earlier, uncon-

taminated fermentation. Provided there is efficient sterilization of fermenta-

tion equipment, distilleries are less likely to suffer the continuing

contamination of successive fermentations caused by re-pitching of culture

yeasts in breweries.

In summary, the most likely and potentially most troublesome microbial

contaminants of malt distillery fermentations are lactic acid bacteria. It is

reasonable to assume from the data of Dolan (1976), without the delay of a

microbial culture, that if gravities are higher and pH values lower than nor-

mal, the cause is a dangerous level of lactic bacteria. Another possible off-

flavour of microbial origin is but yric acid, but the most likely source is the

growth of anaerobic Clostridium spp. in malt or grain residues in the mash

tun. Therefore, although the flavour of an infe cted mash could persist through

fermentation to the final spirit, Clostridia are not strictly contaminants of

fermentations.

Cleaning and disinfection

It is true that various micro-organisms of malt can survive the brief exposure

to mashing temperature, but it is good practice to reduce as much as possible

the other, avoidable, sources of contamination. While mashing, cooking and

distillation equipment should certainly be cleaned to prevent development of

moulds or butyric acid bacteria between periods of use, the equipment listed

in Table 4.6 requires both cleaning and sterilizat ion before each use. Although

written with the brewing industry in mind, the review by Singh and Fisher

(1996) on cleani ng and disinfection is equally applicable to the fermentation

vessels and associated pipework of the distilling industry.

146 Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing

[15:33 13/3/03 n:/3991 RUSSELL.751/3991-004.3d] Ref: 3991 Whisky Chapter 4 Page: 147 114-151

The rough surface of the wood of fermentation vessels, joints between the

planks and right-angled corners at the base encourage accumulation of organic

soil in general and microbial contamination. Although steam is a useful ster-

ilant, a jet of steam has no cleaning effect. In fact, by forming an insulating skin

on the surface of organic soiling, steam may actually protect underlying micro-

organisms. A powerful jet of cold water or, even more effectively, hot water

with added detergent, provides the necessary scouring effect to remove such

deposits (Dolan, 1976; Singh and Fisher, 1996). Subsequently, steaming will

kill most surviving micro-organisms. However, washbacks and other equip-

ment need an appreciable time of steaming to heat up to an effective tempera-

ture, and micro-organisms are not killed instantaneously by heat – even by

steam at 1008C. Therefore at least 30 minutes’ steaming of the washback is

required after cleaning, and preferably longer if possible.

Cleaning and sterilization of the smooth inner surfaces of stainless steel

vessels is more reliable, and now in many distilleries such vessels are

equipped with automatic cleaning-in-place systems, but the choice of steriliza-

tion by steam or lower-temperature chemical sterilants requires some consid-

eration. Although naturally some details are different, and sterilization is

unnecessary, a similar choice applies to cast iron versus stainless steel mash

tuns. The rough surface of cast iron is dif ficult to clean, but residual grain

debris encourages the growth of the anaerobic bacteria that cause butyric acid

off-flavour. Tab le 4.7 lists important considerations for both steel and wooden

washbacks, but ultimately the decision is based on specific local factors.

Finally, at this point of transition between fermentation and the distillation

operations described in Chapter 5 and 6, it is important to prevent contam-

ination of the wash charger vessel and associated pipework to the still.

Although partially protected by the factors discussed above, microbial

growth there is possible, and regular (if not necessarily daily) sterilization

is advisable.

Chapter 4 Yeast and fermentation 147

Table 4.6

Sterilization requirements in distilleries

Process Equipment Type of soil Method of cleaning

Wort cooling Heat exchanger Protein, scale CIP (high-velocity

detergent/sterilant)

Fermentation Washback Yeast, protein,

sugar, scale,

‘beerstone’

CIP

Yeast preparation Mixing vessel Yeast, protein Manual or CIP

Wort transfer Fixed pipeline Protein, sugar CIP (high-velocity

detergent/sterilant)