Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PRODUCTION FOR EXPORT

that the rapid rise in production owed more to metropolitan

pressures than to African self-interest. (This is separate from the

more general question, which will be discussed later, of coercion

to take part in the exchange economy as such.) It is certainly true

that compulsory cotton-growing was the proximate cause of the

great insurrection of 1905 in German East Africa and that in the

British East African territories the element of compulsion, though

rather more tactfully applied, was no

less

present in the early stages

of cotton development. It is also true that the crop was en-

thusiastically promoted by the young Winston' Churchill, then

under-secretary for the colonies and MP for Oldham; that the

British Cotton-Growing Association, a body formed by Lanca-

shire interests and enjoying a small government subvention,

helped to initiate production in both East and West Africa; and

that it was succeeded in

1919

by a fully state-financed organisation,

the Empire Cotton-Growing Corporation, which imparted a bias

towards cotton in agronomic research and extension work all over

the British tropical colonies. The corporation's medallion, which

showed Britannia sitting on her throne while straining black and

brown figures laid bales of cotton at her feet, was a gift to critics

of British colonial egotism. Yet neither the Colonial Office nor

the colonial administrations were in any simple way instruments

of metropolitan business interests; and the administrations had

interests of their own which sometimes pointed in a contrary

direction. For their own part, they would want their subjects to

produce whatever paid them best, because that would make them

more contented and so more easily governed, and also because

the maximising of taxable incomes was conducive to the well-being

of the government

itself.

Thus, though London wanted the

peasants of Northern Nigeria to grow cotton, when most of them

decided to grow groundnuts instead the Nigerian authorities did

nothing

to

impede their choice. And the East African governments

remained keen on cotton-production even when metropolitan

pressures had died away; it is ironic that by the 1920s, when

African cotton-growing really got going, the Lancashire industry

had entered its terminal decline, and most of the new output went

to feed the mills of India and Japan.

The other significant fibre crop was sisal hemp, among whose

functions was to supply the vast amounts of twine that were

needed at that time for the harvesting of temperate-zone cereals.

101

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ASPECTS OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

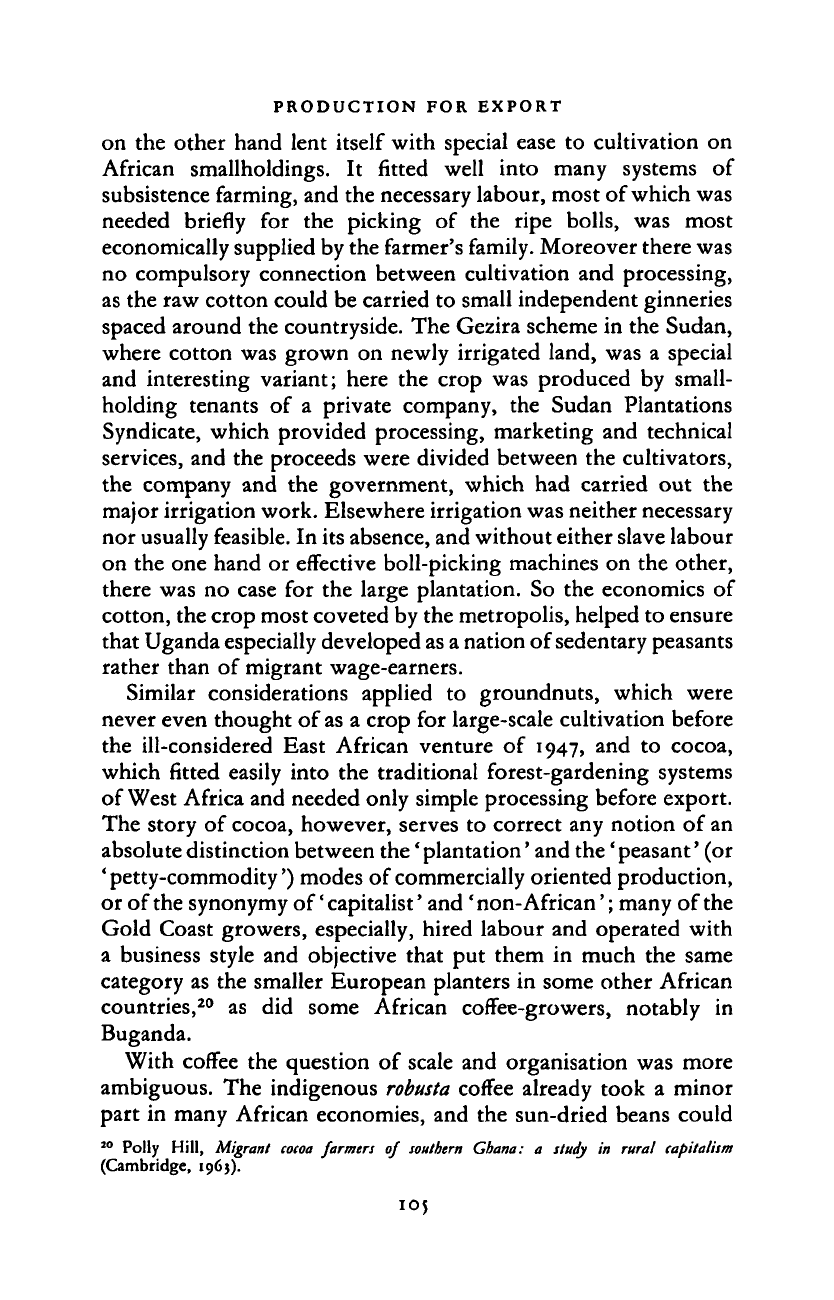

320

280

240

200

160

120

80

40

0

40

30

20

10

COCOA

-

-

/Gold Coast'

/

/

A ; Sao Tome and Principe

/ Nigeria , ,' '

/'. .A

y

v'

\

,-A

»"VFr.

W.

Africa

1910

1920

1930

1940

COFFEE

*•••• Madagascar

" Angola

•ooo Belgian Congo

_ Uganda

Tanganyika

Kenya

Cameroun

Ivory Coast , ,

Ethiopia

1910

1920

1930

1940

80

60

40

20

COTTON

o-o-o Belgian Congo

French Equatorial Africa

*-— Mozambique

Nigeria

— Sudan

Tanganyika

__- Uganda

1910

1920

1930

1940

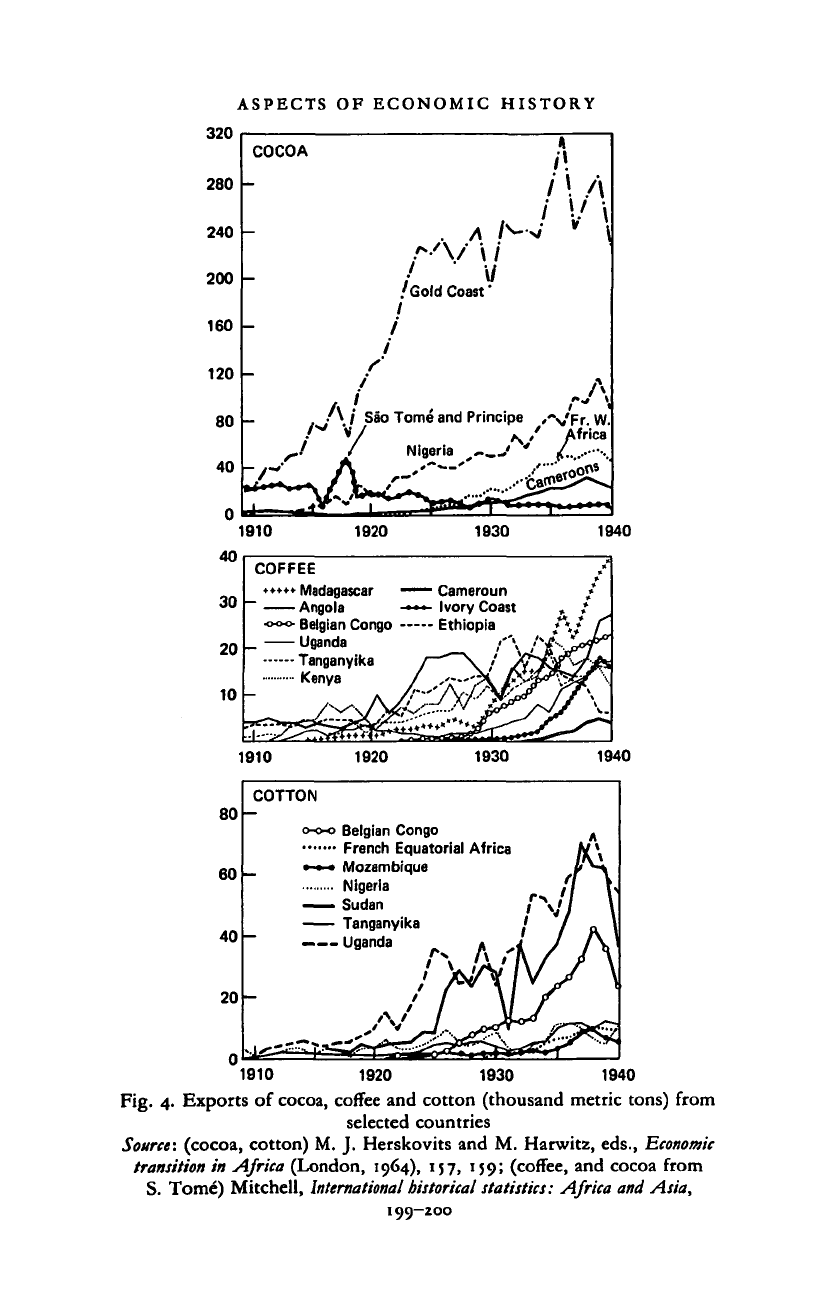

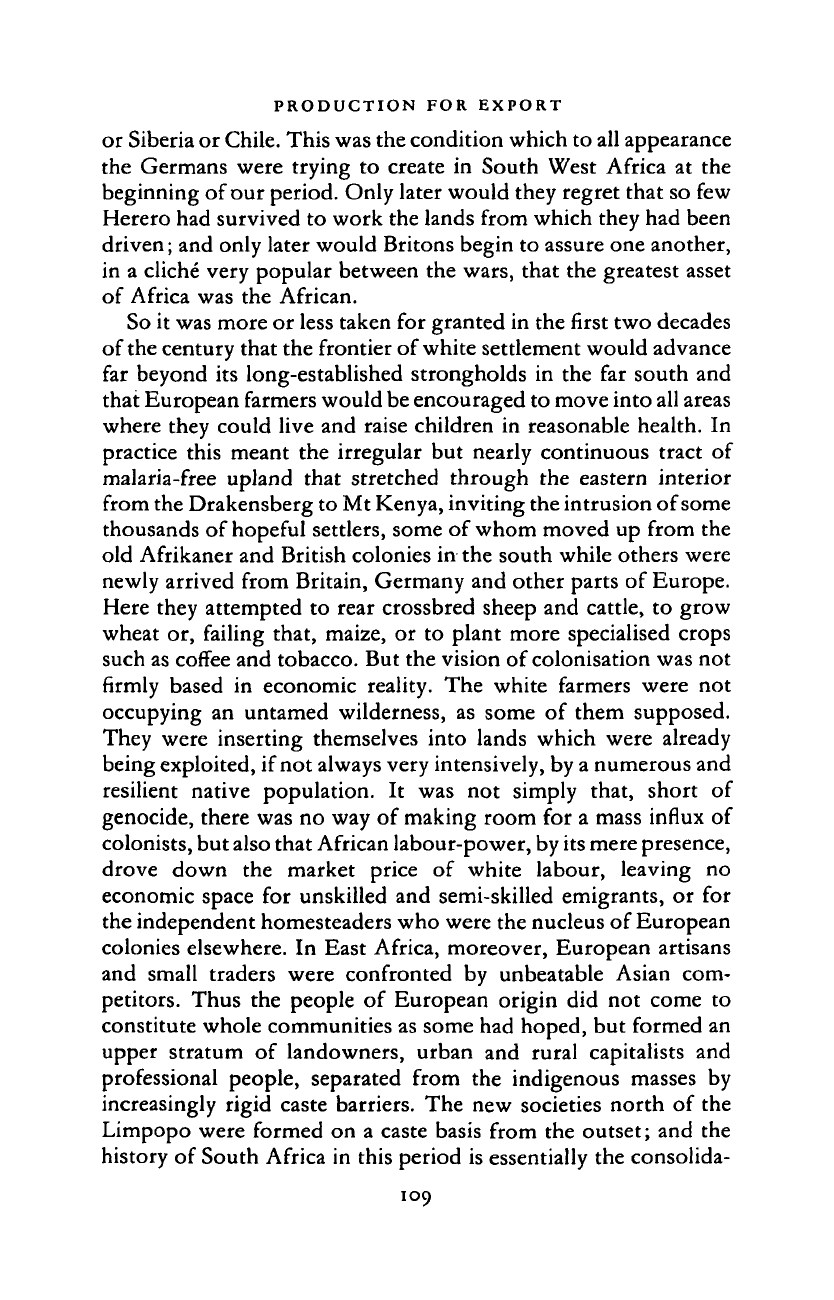

Fig. 4. Exports of cocoa, cofFee and cotton (thousand metric tons) from

selected countries

Source:

(cocoa, cotton) M. J. Herskovits and M. Harwitz, eds.,

Economic

transition

in Africa (London, 1964), 157, 159; (cofFee, and cocoa from

S. Tome) Mitchell, International historical statistics: Africa and Asia,

199—200

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRODUCTION FOR EXPORT

Introduced by German entrepreneurs

to

East Africa,

it

became

the principal export of Tanganyika and a very important product

of Kenya as well.

It

had the great advantage that, being adapted

to semi-arid conditions,

it

could be grown in large areas of East

Africa that were good for little else.

In the production of the crops so far mentioned Africa had no

very special advantage over other regions

of

the tropics

and

sub-tropics; and insofar as African countries had

an

edge over

competitors

in

Asia and South America, or even over southern

Europe and the southern United States, it was because their labour

was cheaper. The same holds

for

tobacco,

the

most valuable

export crop of the Rhodesias.

It

was with certain tree products

that parts of Africa had

a

more truly distinctive role, and

it

was

these that provided the most obvious agricultural success stories.

Cloves had been introduced

to

the hot, wet islands

of

Zanzibar

and Pemba in the early nineteenth century. Despite the fears of

many, the industry survived the abolition of slavery and continued

to provide about

90

per cent

of

the world's supply until

the

expansion of clove-production

in

Madagascar in the late 1930s.

By

a

reversal which might well have become proverbial, large

quantities were shipped

to

Indonesia, the original homeland

of

the spice. Tea was found to grow very well in the wetter western

parts of the Kenya Highlands as well as in the hills around Lake

Nyasa (Malawi), and production was rising rapidly towards the

end of the period. But the main commodities of this kind were

coffee and cocoa. Forest species

of

coffee, native

to

equatorial

Africa, were produced in large quantities, especially on the shores

of Lake Victoria

in

Uganda and Tanganyika,

in

Angola and

in

the Ivory Coast. Mountain coffee, producing fine-flavoured beans

for the European and American markets, was much more exacting

in its requirements. The subtle combination of soil and climate

needed for the production of the most lucrative kinds was found

on the slopes

of

Mt Elgon

in

Uganda, the Aberdare mountains

in Kenya and Kilimanjaro and Meru

in

Tanganyika, and these

became districts of quite exceptional prosperity, though in high-

land Ethiopia the value of the crop was reduced by lack of quality

control. Both kinds of coffee could be grown in the eastern part

of the Belgian Congo, and in 1937-8 this territory produced more

than any other

in

mainland Africa. Still better rents accrued

to

those Africans who had access to land that was favoured by the

103

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ASPECTS OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

cocoa tree, a plant of the American tropical lowlands that does

well in parts of the West African forest zone and in few other

places in the world. By 1905 cocoa-growing had been developing

in the Gold Coast for about three decades and it went on

expanding rapidly for another two, by which time this one

country was producing not far short of half the world's supply.

Cocoa in fact did even more than gold to make the Gold Coast

easily the richest of the ' black' African dependencies; and it also

made south-west Nigeria a much more than averagely prosperous

region, though here the crop was slower to establish itself and

output barely reached a quarter of the Gold Coast total.

In the organisation of colonial agricultural extraction there was

in principle a clear choice of method: primary production could

be left to African smallholders working on their own lands in their

own time, or the producers could be assembled in large enterprises

under capitalist direction. The choice was not easy and the

outcome of competition between the two systems was usually

hard to predict. There was little difference at this time between

alien planter and African cultivator in the equipment or the

techniques of cultivation; insofar as higher output was obtained

on the plantations it was because the work was better organised

and disciplined, not because it received any large application of

capital, and it was often doubtful whether the gain would be

enough to offset the heavy costs of the foreign management by

which it was secured. On the other hand, from the African point

of view it was by no means always clear that

a

higher income could

be gained from independent production than from wage-earning,

and even the non-monetary advantages were not all on the side

of the homestead, when account is taken of the boredom suffered

by young men in rural communities where war had been abolished

and politics had been reduced to triviality.

It was in the processing of the product that advantages of scale

sometimes became significant. Certain specialised crops, namely

tea, sugar, sisal and flue-cured tobacco, were strong candidates for

the plantation mode, because harvesting and processing needed

to be closely linked. (Tea must be treated within hours of plucking

sugarcane and sisal leaves are too bulky to be carried to distant

factories.) Sugar was chiefly grown in Natal, though it was also

produced in Uganda, mostly for local consumption; tea, tobacco

and sisal were mostly grown in East and Central Africa. Cotton

104

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRODUCTION FOR EXPORT

on

the

other hand lent itself with special ease

to

cultivation

on

African smallholdings.

It

fitted well into many systems

of

subsistence farming, and the necessary labour, most of which was

needed briefly

for the

picking

of the

ripe bolls,

was

most

economically supplied by the farmer's family. Moreover there was

no compulsory connection between cultivation

and

processing,

as the raw cotton could be carried

to

small independent ginneries

spaced around the countryside. The Gezira scheme

in

the Sudan,

where cotton was grown

on

newly irrigated land, was

a

special

and interesting variant; here

the

crop

was

produced

by

small-

holding tenants

of a

private company,

the

Sudan Plantations

Syndicate, which provided processing, marketing

and

technical

services,

and the

proceeds were divided between

the

cultivators,

the company

and the

government, which

had

carried

out the

major irrigation work. Elsewhere irrigation was neither necessary

nor usually feasible. In its absence, and without either slave labour

on

the

one hand

or

effective boll-picking machines

on the

other,

there

was no

case

for the

large plantation.

So the

economics

of

cotton, the crop most coveted by the metropolis, helped to ensure

that Uganda especially developed as a nation of sedentary peasants

rather than

of

migrant wage-earners.

Similar considerations applied

to

groundnuts, which were

never even thought

of

as

a

crop

for

large-scale cultivation before

the ill-considered East African venture

of

1947,

and

to

cocoa,

which fitted easily into

the

traditional forest-gardening systems

of West Africa and needed only simple processing before export.

The story

of

cocoa, however, serves

to

correct

any

notion

of

an

absolute distinction between the' plantation' and

the'

peasant' (or

'petty-commodity') modes

of

commercially oriented production,

or of the synonymy

of'

capitalist' and ' non-African'; many of the

Gold Coast growers, especially, hired labour

and

operated with

a business style

and

objective that

put

them

in

much

the

same

category

as the

smaller European planters

in

some other African

countries,

20

as did

some African coffee-growers, notably

in

Buganda.

With coffee

the

question

of

scale

and

organisation

was

more

ambiguous.

The

indigenous

robusta

coffee already took

a

minor

part

in

many African economies,

and the

sun-dried beans could

20

Polly Hill, Migrant

cocoa

farmers

of

southern Ghana:

a

study

in

rural capitalism

(Cambridge,

1963).

105

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ASPECTS OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

be taken without much difficulty

to

central curing works, so there

was

no

need

to

bear

the

costs

of

foreign management

or

investment.

The

more valuable mountain coffee,

on the

other

hand, needed processing

of a

kind which gave some advantage

to units larger than a normal African holding. But the advantage

was not

decisive,

and

the

striking success of African coffee-growers

on the slopes

of

Mt Elgon (Masaba) and Kilimanjaro between the

wars showed that there

was no

real impediment

to

'native

production'

of

this crop.

The

practically exclusive control

of it

by European planters in Kenya and Angola was a function of their

political power much more than

of

superior economic efficiency.

The oil-palm presented problems

of a

rather different kind.

Here organised plantations

had

distinct advantages over

the

traditional West African method of production. Harvesting of the

fruit

was

easier because

the

palms grew less tall when they

did

not have

to

compete with forest trees; yields were higher, more

efficient processing expressed more

oil

from

a

given quantity

of

fruit,

and it

was

oil of

a higher quality, with

a

lower percentage

of free fatty acid. William Lever, anxious

for

larger

and

more

secure supplies

of

his

raw

material, sought

to

overcome

the

last

difficulty

by

setting

up

oil-mills

at

strategic centres

in

Nigeria

in

1911.

But to

make these

pay he

would have needed monopoly

purchasing rights

in

the catchment areas, and this the authorities

refused

to

grant him. After the war he returned

to

the attack, now

seeking land

for

plantations, and was again rebuffed. The episode

shows that official favour did not always go to the most capitalistic

of

the

available forms

of

production.

On the

first occasion

the

refusal reflected the Colonial Office's rooted dislike

of

monopoly

concessions, reinforced

by

opposition from Lever's mercantile

competitors;

but the

post-war controversy elicited ideological

pronouncements about

the

superiority

of

'native production'

21

and these would become settled doctrine

in

British dependencies

during

the

inter-war period, except where European interests

in

land were already entrenched.

Meanwhile Lever

had

secured large grants

of

land from

the

more complaisant Belgian authorities, and his Huileries du Congo

Beige became

the

second pillar, after

the

Union Miniere,

of the

Congolese economy. Since palm plantations were being estab-

21

See especially

Sir

Hugh Clifford, address

to the

Nigerian legislative council, 1921.

106

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRODUCTION FOR EXPORT

lished in Malaya and Indonesia as well, it was feared that West

African export production must succumb to the competition of

more progressive industries. And indeed it steadily lost ground

in the world market. Yet in absolute terms the Nigerian export

at least continued to grow for a long time, even though the

producers were slow to move to more systematic cultivation. For

in fact the old methods fitted in well with their other activities,

and they had the great advantage over capitalist planters of being

able to consume their produce or to trade it locally when the

external market was adverse.

On the whole, then, the classical tropical plantation had only

a modest role to play in colonial Africa. But there were divergent

forms of European enterprise that call for special consideration.

One was the concessionary system, whereby private companies

were in effect granted control over whole populations as well as

the land they lived on. This was of course an expedient by which

metropolitan governments tried to avoid the capital expenses of

colonial development, thereby renouncing its profits and tolerat-

ing the inevitable abuses of private monopoly. The British

' chartered companies' of the late nineteenth century were obvious

examples, and in the Rhodesias a somewhat modified form of

company government persisted until 1923-4. The Congo Inde-

pendent State was a private empire of much the same kind, and

spawned

a

number of sub-empires. King Leopold's role was much

the same as that of Rhodes and Goldie in their respective spheres:

to bring a tract of Africa to the point of development at which

metropolitan finance capital would find it profitable to take over.

In the high colonial period, however, concessionary regimes

survived only under weak colonial governments and in un-

promising regions where population was sparse and few exploit-

able resources were apparent. The chief examples were in French

Equatorial Africa and in Mozambique.

22

Most of the latter

territory was misruled during the first three decades of this

century by private firms, of which the two largest and most nearly

sovereign, the Mozambique and Niassa Companies, came to be

controlled by British and South African financiers. Between 1928

and 1930 the Niassa Company and the lesser concessions were

replaced by the new Salazarist bureaucracy, but the Mozambique

Company retained its prerogatives until 1941.

21

See chapters 7 and 10.

107

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ASPECTS OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

Then there was that special kind

of

entrepreneur, the white

colonist. Whereas the most characteristic type

of

plantation

is

owned by

a

company domiciled

in

the metropolitan capital and

operated by a salaried manager who will eventually return home,

the ' true' colonist or settler is a working farmer who endeavours

to replicate

in a

more spacious land the agricultural patterns

of

his European homeland, thinks

of

himself as belonging

to a

permanent community of emigrants and does not envisage return

either for himself or for his descendants. In practice the distinction

was not clear-cut, for many Europeans in Africa were planters by

virtue

of

the kind of agriculture they practised (coffee-growing

for example) but settlers by virtue of the scale of their operations

and

the

source

of

their finance,

and

also

by

their political

aspirations

and

their social role.

It is

however conceptually

important,

in

that the economic decisions

of

settlers were less

strictly determined by prospects

of

financial profit.

To describe the white settler as

a

'special' type was perhaps

misleading.

It

is true that liberal commentators have commonly

looked on settler Africa, most

of

all

of

course South Africa,

as

a deviation from the norm

of

colonial development that was

represented by West Africa and Uganda and had its archetype in

the great Indian empire. But at the beginning of our period many

Englishmen would have reversed the emphasis, seeing colonisa-

tion as the ideal and the West African mode as a last resort where

malaria and dense native populations kept the door closed

to

settlers. The idea of creating an Indian type of empire in tropical

Africa had appealed only to limited sections of the business and

professional classes, but there was much wider enthusiasm for the

dream of new Australias, where British workers could find

a

better

life,

become efficient suppliers of Britain's needs and high-income

consumers of British goods, and send their strong-grown sons to

help Britain

in

her wars. Likewise the need

for

colonies where

land-hungry peasants could find living-space without being lost

to the Fatherland had played a large part in the rhetoric and some

part

in

the actual calculations of German imperialism.

It

is now

widely believed that the prime object of colonialism was to extract

surplus value from African labour, but at the turn of the century

it seemed that for many colonialists the ideal Africa would have

been one without Africans,

or

one where the aborigines played

no greater part than they did

in

Australasia

or

North America,

108

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRODUCTION FOR EXPORT

or Siberia or

Chile.

This was the condition which to all appearance

the Germans were trying

to

create

in

South West Africa

at

the

beginning of our period. Only later would they regret that so few

Herero had survived to work the lands from which they had been

driven; and only later would Britons begin to assure one another,

in

a

cliche very popular between the wars, that the greatest asset

of Africa was the African.

So it was more or less taken for granted in the first two decades

of the century that the frontier of white settlement would advance

far beyond its long-established strongholds in the far south and

that European farmers would be encouraged to move into all areas

where they could live and raise children in reasonable health.

In

practice this meant the irregular but nearly continuous tract

of

malaria-free upland that stretched through the eastern interior

from the Drakensberg to Mt Kenya, inviting the intrusion of some

thousands of hopeful settlers, some of whom moved up from the

old Afrikaner and British colonies in the south while others were

newly arrived from Britain, Germany and other parts of Europe.

Here they attempted to rear crossbred sheep and cattle, to grow

wheat or, failing that, maize,

or

to plant more specialised crops

such as coffee and tobacco. But the vision of colonisation was not

firmly based

in

economic reality. The white farmers were

not

occupying

an

untamed wilderness,

as

some

of

them supposed.

They were inserting themselves into lands which were already

being exploited, if not always very intensively, by a numerous and

resilient native population.

It was not

simply that, short

of

genocide, there was no way of making room for a mass influx of

colonists, but also that African labour-power, by its mere presence,

drove down

the

market price

of

white labour, leaving

no

economic space

for

unskilled and semi-skilled emigrants,

or

for

the independent homesteaders who were the nucleus of European

colonies elsewhere.

In

East Africa, moreover, European artisans

and small traders were confronted

by

unbeatable Asian com-

petitors. Thus the people

of

European origin did not come

to

constitute whole communities as some had hoped, but formed an

upper stratum

of

landowners, urban

and

rural capitalists

and

professional people, separated from the indigenous masses

by

increasingly rigid caste barriers. The new societies north

of

the

Limpopo were formed on

a

caste basis from the outset; and the

history of South Africa in this period is essentially the consolida-

109

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ASPECTS OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

tion

of a

caste society,

as

nearly

all

white

men

were enabled

to

move

out of

the ranks

of

unskilled labour

in

town

and

country

and

to

become either capitalists

or a

specially privileged stratum

of

the

working class.

Further,

in the

production

of

meat, cereals

and

dairy produce

the white farmers

of

Africa were

at a

serious disadvantage

in

comparison with

the

better-established, lower-cost suppliers

in

other continents. This

did not

seem

to

matter

in our

first decade,

when world demand was rising fast,

but the

glut that developed

between

the

wars created

a

serious crisis. Thus they depended

on

local urban markets, which were

not yet

sufficiently developed

except

in the far

south.

But

here again there

was the

same

problem: Africans were able

to

provision these markets

at

much

lower cost. Technically there

was no

decisive

gap at

this time,

certainly

not a

wide enough

gap to

justify

the far

higher returns

that

the

farmer

of

European origin needed

if he was to

stay

in

business. (Ironically,

it is in the

last twenty years that effective

mechanisation, together with fertilisers, insecticides

and

herbi-

cides,

has

everywhere generated crucial advantages

of

scale

in

cereal farming,

so

that

the

professional, highly capitalised farmer

has been acquiring

an

indispensable economic role

at the

time

when his political privileges were disappearing.) Hence one

of

the

main bones

of

racial contention

in

'settler' Africa

was the

local

market

for

foodstuffs. During the nineteenth century and

the

first

years

of the

twentieth many South African tribesmen

had

gone

a long

way

towards transforming themselves into peasants,

producing systematically

for the

market and sometimes adopting

radically new techniques such as the ox-drawn plough. At the time

this trend was encouraged

by

the authorities, but after 1910k was

deliberately reversed

by

political action; from then

on, the

roles

assigned

to the

African majority were

to be

those

of

subsistence

cultivator and wage-earner, and

no

other.

23

Further north, where

the entry

of

Africans into commercial production

was

slower,

similar policies were adopted, though their application

was

less

rigorous.

It

is

clear that there

was a

close link, almost

a

symbiosis,

between white farming

and the

mining enterprise which alone

could generate

a

sufficient demand

for its

product.

In

Kenya,

13

See

especially Colin Bundy, The

rise

and fall of

the South

African

peasantry

(London,

•979>-

I

IO

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008