Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1930—194°

a pupil of Malinowski, was studying the Bemba, a people

particularly affected by labour migration to the mines. Between

1932 and 1939 the IAI provided from Rockefeller funds 17

fellowships for extended research in Africa. All but three were for

work in British territories, and most were given to social

anthropologists trained by Malinowski in the study of' culture

contact', of whom six were South African, four were German or

Austrian and two were British.

47

Social research in south-eastern

Nigeria, and by Evans-Pritchard in the Sudan, was funded by the

Leverhulme Trust.

Governments also promoted research. In Britain,

a

government

research committee helped in the later 1920s to extend to Africa

the new science of nutrition. A League of Nations report on the

subject in 1935 prompted the Colonial Office to collaborate with

the Medical Research Council and the Economic Advisory

Council in organising a survey in 1938 of nutrition in British

colonies. In probing the causes of malnutrition, the ensuing report

stressed ignorance rather than poverty, despite evidence from

Richards and others that economic pressures could seriously

impair African diets. Nonetheless, there were leading experts who

found good sense in African farming practices, and in any case

there was increasing official concern to improve subsistence

agriculture. The Colonial Development Fund helped to finance,

among other research, ecological surveys in Northern Rhodesia.

In Tanganyika and southern Nigeria administrative officers con-

ducted full-time enquiries into land-tenure. Two academic social

anthropologists were employed by governments: Schapera in

Bechuanaland and Nadel in the Sudan. In 1925 the former German

agricultural research station at Amani in Tanganyika had been

revived. Scientists in government employment gathered at im-

perial conferences and at others held in East and West Africa.

Museums were enlarged or created in the Rhodesias and provided

bases for archaeological research (for which the South African

government had created a department in 1935). In Northern

47

Two IAI fellowships were given to French ethnographers for work in Algeria. Social

research by French academics in tropical Africa in the 1930s consisted only of

a

team

study of the Dogon people, in Soudan, led by Marcel Griaule of the Institut

d'Ethnologie (from which the Musee de I'Homme was formed in 1938). In 1929 the

administrator-anthropologist Henri Labouret wanted to study labour migration from

Upper Volta to the Gold Coast, but the federal government at Dakar took no interest.

Matters improved after the foundation at Dakar in 1938 of the Institut Francais de

I'Afrique Noire.

7

1

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE IMPERIAL MIND

Rhodesia, the initiative of

a

colonial governor led to the foundation

in 1937

of

the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute

for

Social Research;

its first director,

the

social anthropologist Godfrey Wilson,

embarrassed the government by tackling the contentious question

of Africans

in

towns. This episode illustrated

the

distance which

in practice separated colonial governments

and

professional

anthropologists, despite assertions from both sides of belief in

the

value

of

'applied anthropology'.

There was

a

modest growth

of

concern with Africa

in

British

universities,

and in

subjects other than social anthropology.

Rockefeller, which

had

financed

the

expansion

of

the

London

School of Tropical Medicine in the

1920s,

now advanced the study

of African languages

at

the

School

of

Oriental Studies.

At the

London School

of

Economics

the

anthropologist Lucy Mair

lectured

on

colonial administration.

At

Oxford, Coupland's

historical research treated Africa chiefly

as a

field

for

British

philanthropy and diplomacy,

but

his younger colleague Margery

Perham travelled widely on the continent and wrote a major study

of indirect rule

in

Nigeria. Another Oxford lecturer, John Maud,

was commissioned

by

Johannesburg

to

study

its

administration;

a third, Christopher Cox, became director

of

education

in

the

Sudan.

In

1937 Coupland

and

Perham started

an

annual summer

school

on

colonial administration

for

officials

on

home leave.

From Cambridge, the economist

E. A. G.

Robinson contributed

to

the IMC

report

on the

Copperbelt,

and

scientific expeditions

visited

the

East African lakes.

As in

France

and the

USA,

numerous doctoral theses were written

on

African topics.

48

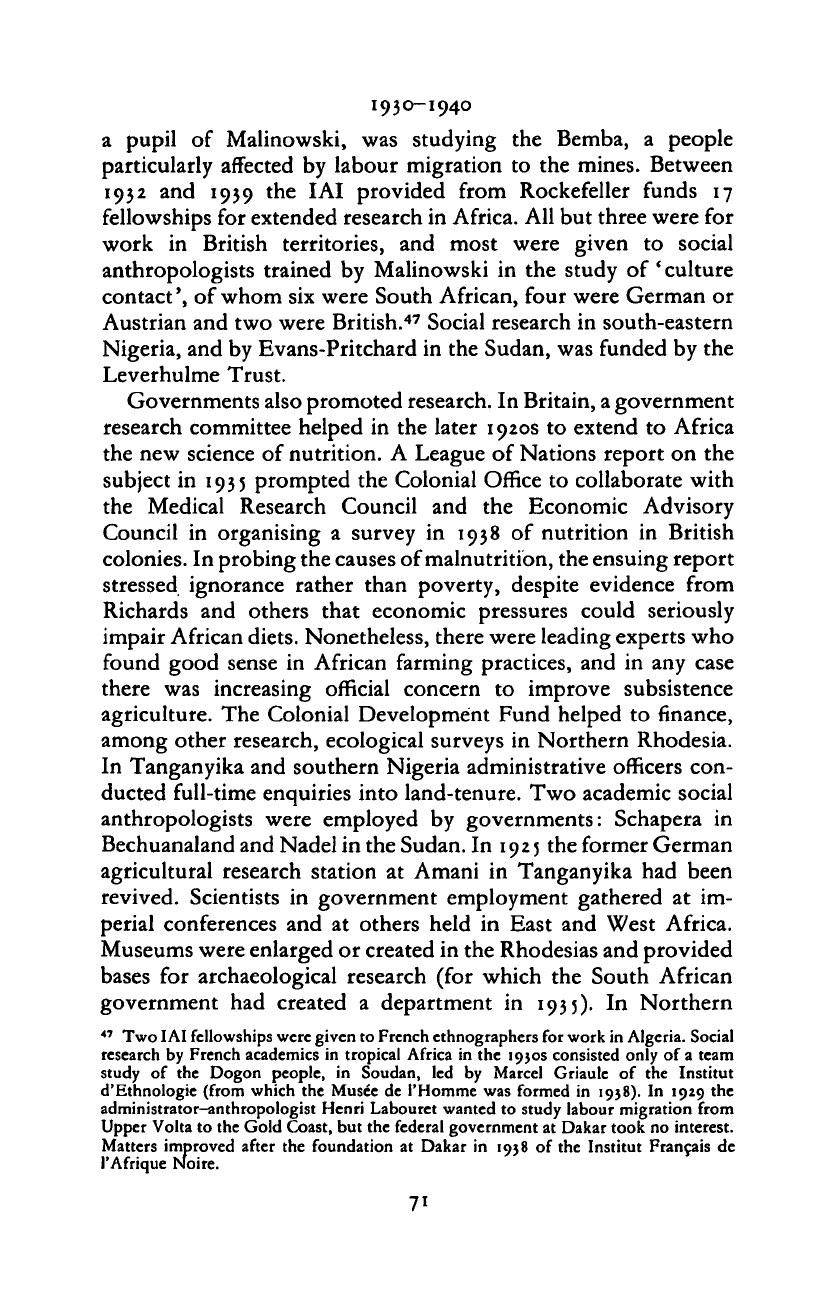

48

British and 1

UK: 1920-40

USA: 1905—40

JS doctoral theses

Total

96

104

Accep-

ted after

1950

70

66

on Africa (excluding

Humanities

and

Social Sciences

64

2O 2) 19

90

22 )5 27

I

•4

ancient

Natural

Sciences

i

1

•

*3

—

4

Egypt):

<

ui

8

8

London

Ji

Oxford

or Cam-

bridge

22

Many of the theses on South Africa were by South Africans, and most of those on Egypt

for British universities were by Egyptians.

72

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1930—194°

Much of the research achieved during the 1930s was drawn

upon for the African Research Survey. This project may be said

to have originated in Smuts's proposal at Oxford in 1929 for a

centre of African studies that would serve the interests of

European governments, but especially that of South Africa.

Funds for this were not forthcoming, but the idea

was

transplanted

and transformed at the Royal Institute of International Affairs

(Chatham House). This had been founded after the war at the

instigation of Lionel Curtis, a member of the

Round Table

group,

and it was he who in 1931 persuaded the Carnegie Corporation

to finance an African research survey. The aim was to examine

the impact on sub-Saharan Africa of European civilisation,

including its 'economic revolution', in the hope that through

better-informed government this impact would help and not harm

Africans. The survey was directed by Sir Malcolm Hailey, until

recently a provincial governor in India. Ironically, in view of the

survey's origins, the appointment thus epitomised the growing

tendency of British rule in Africa to depend on expertise from

India rather than South Africa.

49

The survey resulted in the

publication in 1938 of three volumes: S. H. Frankel's Capital

investment

in Africa and two collective compendia, E. B. Worth-

ington's

Science

in Africa and Hailey's own An African

survey,

which collated information on an international basis from

academics and officials. Meanwhile Chatham House had also

sponsored the first of R. R. Kuczynski's studies of African

population statistics and W. K. Hancock's

Survey

of Commonwealth

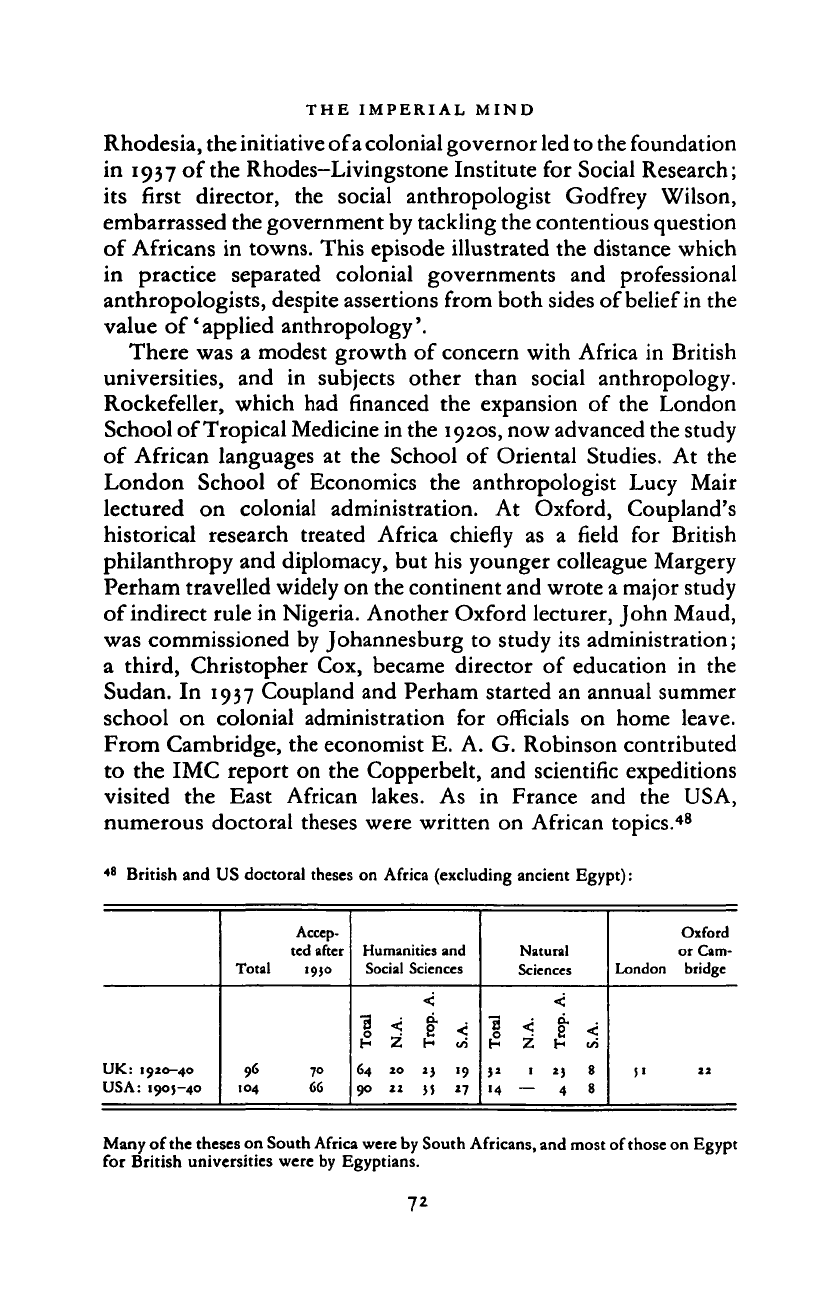

Doctoral theses in law, letters and

Area studied

Maghrib

Africa S. of Sahara

Madagascar

science

Total

355*

>3>

2

46'

for French

1931-40

109

JO

'9

universities,

Law or

letters

323

no

3i

1905-40:

Science

30

21

M

1

j by Arab authors; 85 for University of Algiers

2

} by African authors (incl. 2 from Anglo-Egyptian Sudan)

J

1 by Malagasy author

In addition, there were 1)2 such theses on Egypt (excluding ancient Egypt); at least

90 authors were Arab.

40

Next to Hailey and Pirn, the most influential colonial adviser with Indian experience

was Arthur Mayhew, secretary of the Advisory Committee on Education in the

Colonies, 1929-39.

73

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE IMPERIAL MIND

affairs; this last included searching analyses of economic change

in South and West Africa.

Hailey's An African survey presented an enlightened and

cautiously reformist view of the continent. It was the first British

work to give serious attention to the African empires of other

European powers, which Hailey himself visited during a tour of

Africa in 1935—6. The

Survey

gave no currency to prejudices such

as still survived in officialdom about African indolence or brain

capacity.

50

It confronted many of the implications of economic

change and implicitly at least offered a critique of indirect rule.

The prevailing tone was humane and by no means complacent.

Yet the

Survey

exhibited the faults as well as the virtues of the

mandarin, and it reflected a dominant trend in contemporary

social thought insofar as it implied that Africa was a vast

laboratory for experiments in scientifically controlled social adap-

tation. ' The African' appeared frequently in its pages; individual

Africans, scarcely at all. The existence of African organisations

was barely acknowledged, let alone the diversity of contemporary

African culture. ' Nation-building' was seen as work for adminis-

trators, not agitators. It was inevitable that the

Survey

should have

taken little account of the African past, for this had been neglected

both by historians and by anthropologists, who mostly ignored

unmatched opportunities to record oral historical testimony. But

it was significant that neither Hailey nor Worthington could find

room for any account of such work as had been done on the Iron

Age archaeology of Africa — which now included excavations

at Mapungubwe in the Transvaal and Schofield's studies of

pottery in southern Africa. All in all, what passed for a survey

of Africa was primarily a survey of Europe in Africa.

Hailey's team, for all their distinction, might well have echoed

the recent remark of

a

former official in Northern Rhodesia:' We

...complacently rejoice in our high-mindedness, forgetting that we

are still as arrogantly dictating, still every whit as compelling... '

5I

Indeed, one senior administrator had recently accused himself and

50

Two doctors in Nyasaland argued that one cause of African insanity was excessive

education, and as late as 19)9 the naked and indolent negro still basked in the

condescending sunshine of a history book published by the Colonial Empire Marketing

Board, The story of

the

British

colonial

empire.

51

Frank Melland, in F. H. Melland and Cullen Young, African

dilemma

(London, I9J7),

35-

74

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

his colleagues of being 'too much obsessed with our thoughts,

our teaching, our plans. It is high time we heard a little from the

other side.'" One remarkable purge for spiritual pride was

supplied by a German museum curator who, before fleeing from

Hitler, had sought out representations of white people by African

artists.

53

Besides, Nazi behaviour had itself done much to discredit

beliefs in racial superiority. Colonial rule in Africa was criticised

in books by Leonard Barnes and W. M. Macmillan, both in the

Labour Party's circle of advisers, and in Geoffrey Gorer's account

of travels in French West Africa. The voices of Africans were

mediated through Perham's collection

Ten

Africans

(1936)

and less

directly through the novels of Joyce Cary.

54

But closer contact

was exceptional. Creech Jones (who from 1936 served on the

advisory committee on colonial education) corresponded with

political leaders in West Africa. Jomo Kenyatta and Z. K.

Matthews participated in Malinowski's seminar; Malinowski

himself warned that by ignoring African agitators ' we may drive

them into the open arms of world-wide Bolshevism', and noted

the catalytic effect upon African opinion of Italy's invasion of

Ethiopia.

ss

But between colonial governments and their African

wards dialogue scarcely existed: dissent was commonly treated as

sedition. Even in West Africa, constitutions had stagnated since

the early 1920s, while little came of Governor Guggisberg's bold

plans for Africanising posts in the Gold Coast civil service. To

be sure, African voices had not been wholly impotent: in eastern

and central Africa they had influenced decisions regarding closer

union, while strikes and boycotts compelled some official re-

thinking in Northern Rhodesia and West Africa. But to rely on

the dialectic of neglect, explosion and commission of enquiry was

poor trusteeship by any standard. Against those who claimed that

good government was better than self-government, there were

grounds for arguing that government could not be good unless

it was self-government, or at any rate moving in that direction.

52

C. C.

Dundas (chief secretary, Northern Rhodesia)

to the

International Colonial

Institute, 19)6 (quoted

by

Rosaleen Smyth, 'The development

of

government prop-

aganda

in

Northern Rhodesia up

to

19J 3' (Ph.D. thesis, University

of

London, 198)),

43-

53

Julius Lips, The savage hits back (London and New Haven, 1937).

54

Aissa saved (1932),

An

American visitor (1933), The African witch (1936),

Mr

Johnson

(1939). Cary had been

in

the Nigerian political service from 1913

to

1920.

55

Introduction

to

Jomo Kenyatta, Facing Mount Kenya (London, 1938),

x.

75

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE IMPERIAL MIND

All

the

same,

An

African

survey

did induce some forward

thinking. It acknowledged that' the political future which British

policy has assigned to the African colonies must be understood

to

be

that

of

self-government based

on

representative

institutions'.

56

It

prudently refrained from attaching any sort of

time-scale to this future, but it drew attention to the difficulty of

reconciling elected legislatures with the structures of indirect rule.

In October 1939 this problem

was

discussed

at a

meeting

convened by the colonial secretary, Malcolm MacDonald. This

exposed sharp disagreement. The officials, supported by Coup-

land, pressed the claims of the African intelligentsia to a share of

power at the centre; Perham and Lugard wished to confine their

scope to local government. Hailey was despatched on another tour

of Africa, to make a report on which to base a policy. Meanwhile,

the

Survey

had given weighty backing to those who believed that

British investment in colonial development under the act of 1929

should be increased and extended in range: a new bill was drafted

in 1939.

In September the Second World War broke out. Colonial

questions, so far from receding into the background, seemed more

urgent than ever. Reform was needed, both to forestall subversion

and to advertise to the world Britain's fitness to be a great power.

The Colonial Development and Welfare Act was passed in July

1940.

War, and the threat of war, also changed Britain's attitude

to

the

French empire

in

Africa.

An

early sign

of

awakening

interest had been an academic enquiry in 1935 into education in

French West Africa. But the War Office continued

to

regard

France as the major threat to British power in Africa. By 1937

this was patently absurd, for

a

real menace to Britain's position

in Egypt, the Sudan and Kenya was now posed by the Italians

in Libya and Ethiopia. In 1938—9 air services connected French

and British colonial capitals between Dakar and Khartoum.

In

October 1939 MacDonald made history by visiting the French

colonial minister. But

the

time

for

such exchanges was fast

running out. Paris would soon cease to matter; what Britain now

needed in Africa was the goodwill of the USA.

s6

Hailey,

An

African

survey,

1,659.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

2

ASPECTS

OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

FOUNDATIONS OF THE COLONIAL EXPORT ECONOMY

The economic changes that took place

in

Africa

in

the period

under review have been summarised in terms of varied implication,

as the economic revolution, the second stage of Africa's involve-

ment

in the

world economy,

the

intensification

of

dependent

peripheral capitalism, the completion

of

the open economy,

or

simply

as

the cuffing

of

Africans into the modern world.

1

The

concrete fact, however, from which these descriptions take off in

different directions is not itself in much dispute. Between 1905-9

and 1935—9, exports from African countries between the Sahara

and the Limpopo

2

increased by about five times

in

value and

by

nearly

as

much

in

volume; import values rose

by

some three-

and-a-half times, import volumes between two-and-a-half and

three times. Total trade thus grew

in

real terms

at an

annual

average rate of

a

little over

3

per cent.

3

At first sight this is hardly

a momentous expansion. For even though

it

was nearly double

the rate of growth of world trade taken as a whole, it started from

such low levels that the global impact was hardly perceptible, and

was not of primary significance for the economies of the colonial

powers themselves; before

the

Second World War, trade with

1

This selection alludes

to

the work

of

Allan McPhee, The

economic revolution

in British

West Africa (London, 1926) and

S. H.

Prankel, 'The economic revolution

in

South

Africa', chapter

3 of

his Capital

investment

in Africa (London, 1938);

A. G.

Hopkins,

An

economic

history

of

West Africa (London, 1973), 168 and ch.

6; I.

Wallerstein, 'The

three stages

of

Africa's involvement

in

the world economy',

in P. C.

Gutkind and

I.

Wallerstein (eds.), The political

economy

of

contemporary

Africa (London, 1976), 30-J7

(cf.

Frankel, Capital investment,

ch. j,

'Africa joins

the

world economy'); Samir Amin,

' Underdevelopment and dependence in black Africa',

Journal

of Modern African Studies,

1972,

io, 4,

J03-24;

R. E.

Robinson and

J.

Gallagher, 'The partition

of

Africa',

in

F.

H.

Hinsley (ed.), New Cambridge

modern

history,

XI

(Cambridge 1962), 640.

1

This chapter pays

no

heed

to

Mediterranean Africa, nor, regrettably,

to

the Horn.

South Africa, where the decisive changes began earlier,

is

excluded from this sentence

but not from the chapter.

1

These figures, especially the volume ones, must

be

taken

as

very approximate.

77

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ASPECTS OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

sub-Saharan Africa (South Africa still excluded) never accounted

for a twentieth part of the United Kingdom's exchanges.

4

So

inconspicuous, indeed, were the short-term and even the medium-

term commercial gains accruing from the European conquest of

tropical Africa that many metropolitan observers, unaware that

the investment was a long-term pre-emption, have concluded

either that it was a mistake or that it must have been undertaken

for reasons that were not commercial. For Africa, however, none

of the innovations of

the

early and middle colonial periods, apart

from the spread of literacy, compared in importance with the

advance of overseas trade, to which most other economic changes

were directly related either as condition or as consequence.

The most crucial of the conditions was the conquest

itself,

that

is to say the incorporation of African societies into larger and

solider systems of political order than had existed before. (The

reference is to the colonial empires, not to the individual units

of colonial administration, which were not always decisively

larger than earlier African states.) The linkage is unmistakable but

its nature may need to be clarified. It was not primarily that trade

was no longer interrupted by warfare or banditry, for in fact

long-distance commerce had often been conducted across dis-

turbed African frontiers. It was rather that most Africans were

now released from the posture of defence and enabled to

concentrate on productive enterprise. That is not to say that they

had formerly spent all or most or even any large part of their time

fighting one another, but readiness to fight had been the first

obligation of males in the most vigorous period of their lives and

work had had to take

a

subordinate place. In economic terms, the

conquest meant (and this change appeared to be permanent) that

the function of protection was specialised, taken away from the

general body of adult males and assigned to very small numbers

of soldiers and policemen, whose organisation and weapons gave

them an unchallengeable monopoly of force. For the others, there

4

See chapter i, table i. For relations with other metropolitan powers see chapters 6

and 7 (France), 9 (Belgium) and 10 (Portugal). The gold-mining boom in the 1950s

greatly increased South Africa's share of the British export market; in 1935-8 it

averaged 8.7 per cent, as against only 4.7 per cent for the rest of sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1925—8 the respective figures had been 4.8 and 4.1. (Calculated from B. R. Mitchell

andP. Deane, Abstract ofBritish historical statistics (Cambridge, 1962), 284, j2o;Mitchell,

International historical statistics: Africa and Asia, 414.)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FOUNDATIONS

was a loss of autonomy, even of the sense of manhood, as well

as unprecedented possibilities of oppression, but the economy of

human energy was very great.

Above all, the new order made long-term investment possible.

It is no accident that tree-crops such as coffee and cocoa were not

planted on any scale on the mainland of Africa until there was

no longer a risk that they would be cut down by raiders just as

they were coming into bearing. But most important was the

investment in transport which, as most colonial rulers knew, was

what colonial rule was mainly for. As Adam Smith had remarked,

5

nature had so constructed the African continent that most places

were a long way from sea or navigable river, and so from what

in his and all earlier times had been by far the cheapest mode of

transport. In addition, diseases of stock were so prevalent that

between the camels of the desert and the horses and trek-oxen of

the far south there were no load-moving animals except a few

donkeys. Tropical Africa thus moved straight from head porterage

to the railway and the motor lorry. To an extent which can hardly

be overstated, it is today the creation of these devices, and

especially the former. Railways are uniquely large, expensive and

vulnerable pieces of fixed capital, which demand political security

over very wide areas. They are necessarily at least partial

monopolies; but even so, since they yield mainly external econo-

mies,

the profits from their construction are more likely to accrue

to other enterprises than to the

builders.

For all these reasons, even

in societies otherwise committed to pluralistic capitalism, they

have always been closely regulated, usually at least partly financed

and very often built and managed by the state. More than

anything else, it was the exigencies of railway-building that had

brought the European states into Africa, persuading their ruling

classes that they must move from informal to formal empire in

a continent that could not provide the political cover needed for

the revolution in transport without which the exploitation of its

resources could not proceed much further.

The converse is also true. Once colonial governments had been

established they had to build railways in order to justify their

existence, and sometimes in order to be able to govern. There was

in consequence some construction which, as will appear, was

5

The wealth of

nations

(1905 edition), 16.

79

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ASPECTS OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

premature or wrongly located and yielded too little trade to justify

the heavy burden of debt charges imposed on the peoples it was

supposed to serve. Most lines, however, easily vindicated

themselves, in the sense that they gave access to resources which

would otherwise have been unusable and brought the territories

far more revenue than they took out.

Railway-building was in full swing well before 1905, and by

1914 the crucial thrusts into the interior had mostly been

completed. As in all forms of development, South Africa was far

ahead of the rest of the continent; and even at the end of the period

it contained nearly half the total mileage south of the Sudan

(13,600 miles out of 30,700). Construction had of course been

undertaken mainly to connect Kimberley and the Rand with the

outer world, and had been stimulated by competition between the

business and political interests identified with the ports of Cape

Town, Port Elizabeth, East London, Durban and Lourenco

Marques. Already by 1914, however, there was a true network,

with lateral and interlocking lines as well as those leading to the

coast, promoting activities other than mineral export alone.

Elsewhere there were at that time only tentative and isolated

ventures, undertaken at the lowest possible cost and with no

overall planning, each administration probing from its coastal

base towards real or imagined sources of future wealth in the

interior. Typically the railway struggled to the nearest stretch of

navigable water, where it thankfully handed over to steam-boats.

Thus the famous 'Uganda' Railway, having opened up the Kenya

Highlands on its way, reached the easternmost gulf of Lake

Victoria in 1901, bringing much of the fertile lake basin within

reach of world markets. The Germans, though they pushed a line

past the Usambara mountains to the base of Kilimanjaro by 1911,

were slower to traverse the unpromising central and western parts

of their East African sector and did not reach Lake Tanganyika

till the eve of war in 1914; and by the next year the lake was also

linked to the Atlantic by four separate bits of railway and three

smooth stretches of the Congo river. Meanwhile the Nyasa

country had been reached by a line which started from the

just-navigable lower Shire, and the South African system had sent

out a long tentacle through the Rhodesias, reaching Bulawayo in

1897,

Salisbury (Harare) in 1902 and the Broken Hill mine in 1906;

Salisbury had also been provided with a much shorter link to the

80

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008