Research methods in education (hand book)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

-

1 1 1 -

APPENDIX: STEPHEN BALL ON BANDING AND

SOCIAL CLASS AT BEACHSIDE

COMPREHENSIVE

1 INTRODUCTION

Below we have reprinted an extract from Stephen Ball’s book, Beachside Comprehensive. By way

of a preface to this, the following is Ball's account of the focus of his research, which he provided in the

introduction to the book:

This is a detailed study of a single co-educational comprehensive school, referred

to under the pseudonym of Beachside Comprehensive. The overall aim of the

study is to examine the processes of comprehensive schooling; that is to say, I am

concerned with the dynamics of selection, socialization and change within the

school as these processes are experienced and dealt with by the pupils and their

teachers. The stress is upon the emergent nature of social interaction as well as the

playing out of social structural and cultural forces in the school. Several specific

aspects of the school are addressed: the impact of selective grouping upon the

pupils' experience of schooling, focusing in particular on the different school

careers of the pupils allocated to different ability groups; the introduction of

mixed-ability grouping into the school; and the impact of this on the pupils'

experiences of schooling.

In general terms the book takes up the central question of the works of Lacey

(1970) and Hargreaves (1967), that is, how one can study the social mechanisms

operating within a school and employ such knowledge to explain the

disappointing performance of working-class pupils. Social class emerges as a

major discriminating factor in the distribution of success and failure within the

school examined here. Social class differences are important in terms of allocation

to ability groups, the achievement of minor success roles, entry into O-level

courses, examination results, early leaving, and entry into the sixth form and A-

level courses. However, this study is not concerned simply with the way in which

these differences are manifested in terms of rates of achievement or levels of

access to high-status courses, but rather with the processes through which they

emerge in the school.

(Ball, S.J., 1981,

Beachside Comprehensive: a case study of secondary schooling,

Cambridge

, Cambridge University Press, p. xv)

2 EXTRACT FROM BEACHSIDE COMPREHENSIVE

The extract from Ball’s book reprinted below deals with a very small part of the topic with which

the book is concerned: the allocation of children to ability bands on entry to Beachside.

It is important [...] to look at the way in which the pupils are allocated to their

bands in the first year. This takes place on the basis of the reports and

recommendations of the primary school teachers and headmasters of the four

schools that provide Beachside with pupils. Almost all of the pupils who enter the

first year at Beachside come from the four ‘feeder’ primary schools within the

community: North Beachside, South Beachside, Iron Road and Sortham. In the

cohort with which we are concerned here, the original distribution by school and

allocation to bands is presented in Table 2.4 below.

-

1 1 2 -

Table 2.4 Allocation of pupils to bands according to primary school

S. Beachside

N. Beachside

Iron Road

Sortham

Others

Total

Band 1

Band 2

Band 3

Total

33

32

17

82

(29%)

36

16

7

59

(21%)

37

52

15

104

(36%)

11

13

4

28

(10%)

4

4

4

12

(4%)

121

117

47

285

(100%)

There is no significant relationship between primary school of origin and the allocation to bands.

The process of negotiation of recommendations and allocation to bands was done by the senior mistress at

Beachside. Where the numbers of pupils recommended for band 1 was too large, the primary headmasters

were asked to revise their recommendations until an acceptable distribution of pupils in each band was

obtained. When they arrived at the secondary school, the pupils went immediately into their banded

classes.

The primary school heads sent us lists with their recommendations for band 1,

band 2 and band 3; it was up to us to try and fit them into classes. If there were

too many in one band, then we had to go back to the primary heads to ask if all

the list was really band 1 material and that way the bands were allocated and then

they were broken into classes alphabetically. There was a lot of movement

between the classes at the end of the first term, but very little movement between

bands.

(Senior mistress)

Thus Beachside carried out no tests of its own; the primary schools acted as selecting institutions,

and Beachside, initially at least, as the passive implementer of selection. Three of the four primary

schools did make use of test scores in the decision to recommend pupils for bands, and these were passed

on to Beachside on the pupils’ record cards, but these test scores were not the sole basis upon which

recommendations were made. Teachers' reports were also taken into account.

[…]

The possibility of biases in teachers’ recommendations as a means of allocating pupils to

secondary school has been demonstrated in several studies. For instance, both Floud and Halsey (1957)

and Douglas (1964) have shown that social class can be an influential factor in teachers’ estimates of the

abilities of their pupils. The co-variation of social class and 'tested ability' in this case is examined below.

The practice adopted by the majority of social researchers has been followed here, in taking the

occupation of the father (or head of household) as the principal indicator of pupils’ social class

background. Although this is not an entirely satisfactory way of measuring social class, the bulk of

previous research seems to indicate that, in the majority of cases, the broad classification of occupations

into manual and non-manual does correspond to the conventional categories – middle-class and working-

class. For the sake of convenience, I have adopted these social class categories when describing the data

of this study

11

.

[…]

Beachside was a streamed school until 1969, and was banded at least to some extent until 1975. It

was not surprising, then, to find that, as analysis in other schools has shown, there is a significant

relationship between banding and social class. If the Registrar General’s Classification of Occupations is

reduced to a straightforward manual/ non-manual social class dichotomy for the occupations of the

parents of the pupils, then the distribution of social classes in 2TA [a Band 1 group] and 2CU [a Band 2

group], the case-study forms, is as shown in Table 2.5.

11

All responses that could not be straightforwardly fitted into the Registrar General’s classifications – e.g. ‘engineer’, ‘he

works at Smith's factory’ – were consigned to the Unclassified category, as were the responses ‘deceased’, ‘unemployed’, ‘I

haven’t got a father’, etc.

-

1 1 3 -

Table 2.5 Distribution of social classes across the case-study forms 2TA and

2CU

Form

I

II

IIIn

Total non-

manual

IIIm

IV

V

Total manual

Unclassified

2CU

2TA

5

2

10

3

5

2

20

7

12

15

–

8

–

3

12

26

–

–

There are 20 children from non-manual families in 2CU compared with 7 in 2TA, and 12 from

manual families in 2CU compared with 26 in 2TA. This is a considerable over-representation of non-

manual children in 2CU; a similar over-representation was found in all the Band 1 classes across this

cohort and in previously banded cohorts

12

. Thus on the basis of reports from junior schools, the tendency

is for the children of middle-class non-manual families to be allocated to Band 1 forms, whereas children

from manual working-class homes are more likely to be allocated to Bands 2 or 3.

[…]

One of the main platforms of comprehensive reorganisation has been that the comprehensive

school will provide greater equality of opportunity for those with equal talent. Ford (1969) suggests that

the most obvious way of testing whether this is true is ‘by analysis of the interaction of social class and

measured intelligence as determinants of academic attainment’. If the impact of social class on

educational attainment is greater than can be explained by the co-variation of class and IQ, then the

notion of an equality of opportunity must be called into question.

There were no standard IQ tests available for the pupils at Beachside

13

, but, as noted above, three

of the four ‘feeder’ primary schools did test their pupils. There was a great variety of tests used, for

reading age, reading comprehension, arithmetic and mathematics. Each pupil’s record card noted a

selection of these test-scores, but only in a few cases were results available for the whole range of tests.

The clearest picture of the interaction between social class, test-scores and band allocation were

obtained by comparing pupils who scored at different levels. Taking N.F.E.R. Reading Comprehension

and N.F.E.R. Mathematics, the co-variation of social class and test-scores within Band 1 and Band 2 is

shown in Tables 2.6 and 2.7. By extracting the 100-114 test-score groups, the relationship between social

class and band allocation may be tested. This suggests a relationship between banding and social class at

levels of similar ability. Taking the mathematics test-scores, there is also a significant relationship.

Altogether, the evidence of these test-scores concerning selection for banding was far from conclusive;

the result is to some extent dependent upon which test is used. It is clear, however, that social class is

significant, and that ability measured by test-score does nottotally explain the allocation to bands. This

falls into line with the findings of Ford (1969) and others that selection on the basis of streaming in the

comprehensive school, like selection under the tripartite system, tends to underline social class

differentials in educational opportunity. However, my work with these results also suggests that, to some

extent at least, findings concerning the relationships between test-performance and social class must be

regarded as an artefact of the nature of the tests employed, and thus the researcher must be careful what

he makes of them.

Table 2.6 Banding allocation and social class, using the N.F.E.R. Reading

Comprehension Test

Band 1

Band 2

Test-score

Working-class

Middle-class

Working-class

Middle-class

115 and over

100 – 114

1 – 99

3

10

5

7

12

1

1

16

24

0

2

5

18

20

41

7

12

The distribution of social class across the whole cohort is presented in Table N2.

13

IQ testing was abandoned by the Local Authority in 1972.

-

1 1 4 -

Table 2.7 Banding allocation and social class, using the N.F.E.R. Mathematics

Test

Band 1

Band 2

Test-score

Working-class

Middle-class

Working-class

Middle-class

115 and over

100 – 114

1 – 99

5

15

1

8

13

0

0

15

25

0

3

1

21

21

40

4

N.F.E.R. Reading Comprehension Test (scores 100 – 114)

Working-class

Middle-class

Band 1

Band 2

10

16

12

2

X

2

= 8.2, d.f. = 1, p < 0.01

C

= 0.41

N.F.E.R. Mathematics Test (scores 100 – 114)

Working-class

Middle-class

Band 1

Band 2

15

15

13

3

X

2

= 4.28, d.f. = l, p< 0.05

С

= 0.29

Notes:

1.

All responses that could not be straightforwardly fitted into the Registrar

General’s classifications – e.g. ‘engineer’, ‘he works at Smith's factory’ – were

consigned to the Unclassified category, as were the responses ‘deceased’,

‘unemployed’, ‘I haven’t got a father’, etc.

2.

The distribution of social class across the whole cohort is presented in Table

N2.

Table N2. Distribution of social classes across the second-year cohort, 1973-4

I

II

IIIn

Total non-

manual

IIIm

IV

V

Total manual

Unclassified

2CU

2GD

2ST

2FT

5

4

–

2

10

8

2

6

5

5

32

10

20

17

5

18

12

12

14

11

–

–

3

2

–

–

–

–

12

12

17

13

–

4

8

3

Band 1

11

26

23

40

49

5

0

54

15

2LF

2BH

2WX

2TA

–

2

1

2

4

2

2

3

1

6

4

2

5

10

7

7

13

12

15

15

6

4

5

8

1

–

1

3

20

16

21

26

8

8

3

–

Band 2

5

11

13

29

55

23

5

83

19

2UD

2MA

–

2

2

2

4

–

6

4

6

5

5

4

–

–

11

9

4

2

Band 3

2

4

4

10

11

9

–

20

6

The questionnaire on which this table is based was not completed by nine pupils

in the cohort. The relationship between banding and social class is significant

X

2

= 20, d.f. = 2, p < 0.001.

3.

IQ testing was abandoned by the Local Authority in 1972.

-

1 1 5 -

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DOUGLAS. J. W. B. (1964) The Home and the School: a study of ability and attainment in the

primary school, London, MacGibbon and Kee.

FLOUD, J. and HALSEY, A. H. (1957) ‘Social class, intelligence tests and selection for

secondary schools’, British Journal of Sociology, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 33-9.

FORD, J. (1969) Social Class and the Comprehensive School, London, Routledge and Kegan

Paul.

HARGREAVES, D. H. (1967) Social Relations in a Secondary School, London, Routledge and

Kegan Paul.

LACEY, C. (1970) Hightown Grammar, Manchester, Manchester University Press.

(Ball, S. J. (1981) Beachside Comprehensive: a case study of secondary schooling, Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press, pp. 29-34)

-

1 1 6 -

PART 2.

PRACTICAL GUIDELINES FOR

PRACTITIONER RESEARCH

INTRODUCTION

The first four sections of this Part provide guidance on research design and appropriate ways of

collecting evidence. Section 1 introduces you to the various research traditions in education and discusses

some factors that need to be taken into account when designing practitioner research. Section 2 is about

documentary analysis and the use of written documents as evidence. Section 3 contains advice about

interviewing techniques and questionnaire design. Section 4 examines how you can collect evidence by

watching and recording what people do and say. It offers advice on observation, recording and analysing

classroom talk, and using children's work as a source of evidence. Section 5 offers advice on the

interpretation, analysis and presentation of evidence.

As well as providing advice on collecting and analysing evidence, the various sections contain

many examples of practitioner research. Some of these have been drawn from the work of the teachers

who helped develop the material, while others come from published accounts of practitioner research in

books and journals.

1.

ABOUT PRACTITIONER RESEARCH

1.1. INTRODUCTION

This section provides a brief introduction to practitioner research and offers general advice on how

to design an inquiry which is ethically sound and which will provide reliable and valid information. You

will probably find it most useful to skim through the whole section first before going on to reread sub-

sections which you find particularly interesting or challenging.

1.2. WHY PRACTITIONER RESEARCH?

Practitioner research is a relatively new recruit to the many traditions of educational research. As

its name implies, practitioner research is conducted by teachers in their own classrooms and schools. It is

carried out 'on-the-job', unlike more traditional forms of educational and classroom research where

outside researchers come into schools, stay for the duration of the research project and then leave. As

David Hopkins comments, 'Often the phrase "classroom research" brings to mind images of researchers

undertaking research in a sample of schools or classrooms and using as subjects the teachers and students

who live out their educational lives within them' (Hopkins, 1985, p. 6). Similarly, Rob Walker maintains

that much of what passes for educational research, 'is more accurately described as research on education'

rather than research 'conducted primarily in the pursuit of educational issues and concerns' (Walker, 1989,

pp. 4-5).

When it comes to the kind of 'classroom research' described by Hopkins and Walker, the teacher

or school has little or no control over the research process. The subject, scope and scale of the

investigation are set by the outside agency to which the researchers belong, and although the research

findings themselves may be communicated to participating schools, often they are of little relevance or

direct benefit to the people teaching and learning in those schools. By contrast, practitioner research is

controlled by the teacher, its focus is on teaching and learning or on policies which affect these, and one

of its main purposes is to improve practice. It also has another important purpose: it can help develop

teachers' professional judgement and expertise. Hopkins expresses this aspect of practitioner research in

the following words:

Teachers are too often the servants of heads, advisers, researchers, text books,

curriculum developers, examination boards, or the Department of Education and

Science among others. By adopting a research stance, teachers are liberating

themselves from the control position they so often find themselves in ... By taking

a research stance, the teacher is engaged not only in a meaningful professional

development activity but [is] also engaged in a process of refining, and becoming

more autonomous in, professional judgement.

-

1 1 7 -

(Hopkins, 1985, p. 3)

'Practitioner research' has its origins in the teacher researcher movement of the early 1970s, which

focused on curriculum research and development, and the critical appraisal of classroom practice through

'action research' (e.g. The Open University, 1976; Stenhouse, 1975). A key feature of action research then

and now is that it requires a commitment by teachers to investigate and reflect on their own practice. As

Nixon notes, 'action research is an intellectually demanding mode of enquiry, which prompts serious and

often uncomfortable questions about classroom practice' (1981, p. 5). To engage in action research you

need to become aware of your own values, preconceptions and tacit pedagogic theories. You also need to

make a genuine attempt to reflect honestly and critically on your behaviour and actions, and to share these

reflections with sympathetic colleagues. Trying to be objective about one's own practice is not at all easy.

As Gates (1989) has shown, however, developing habits of critical self-reflection makes an enormous

contribution to teachers' confidence and professional expertise.

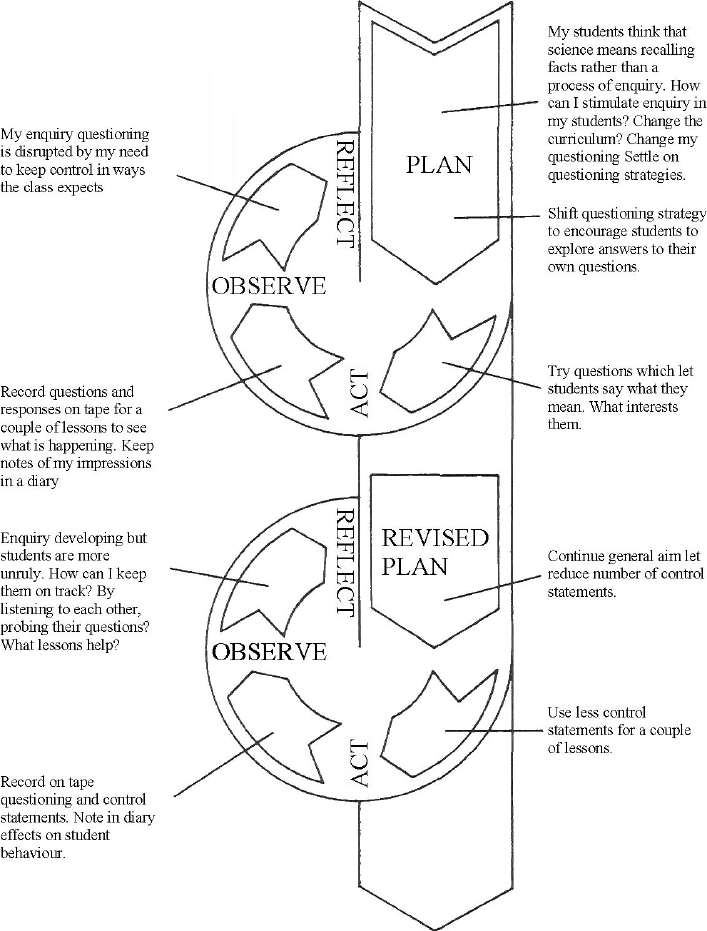

Like other forms of research, action research involves identification of problems, collection of

evidence, analysis and diagnosis, interpretation using theory, and the communication of findings to

audiences outside the researcher's immediate working context. It is unlike more conventional research in

that most problems usually arise directly from practice rather than from published theory. Its main

purpose is to identify appropriate forms of action or intervention which may help solve those problems.

Once an appropriate form of action is identified, it must be implemented, and its effectiveness closely

monitored. If the intervention is successful, it might necessitate a change in practice. This in turn may

raise new problems which must be solved and so on. These recursive processes make up what is know as

the 'action-research cycle'. Figure 1 gives an example of an action-research cycle.

1.3. RESEAECH GROUND

In the first of a recent series of articles examining the nature of research in education, Michael

Bassey states that:

In carrying out research the purpose is to try to make some claim to knowledge; to

try to show something that was not known before. However small, however

modest the hoped for claim to knowledge is, provided it is carried out

systematically, critically and self-critically, the search for knowledge is research.

(Bassey, 1990, p. 35)

While Bassey's definition of research as 'the search for knowledge' is a very loose one, he qualifies

this definition by insisting that all research must be systematic and critical, and by claiming that it must

conform to the following set of rules:

1.

Any research inquiry must be conducted for some clearly defined purpose.

It should not be a random amassing of data but must entail a planned attempt to

arrive at answers to specific questions, problems or hypotheses.

2.

When conducting an inquiry data should be collected and recorded

systematically, so that, if necessary, it can be checked by others.

3.

There should be a clear rationale or theory informing the way the data is

analysed.

4.

Researchers must critically examine their evidence to make sure that it is

accurate, representative and reliable.

5.

Researchers must be self-critical and should scrutinize their own assumptions,

methods of inquiry and analysis, and ways of presenting their findings.

6.

As the purpose of research is 'to tell someone something that they didn't know

before', then researchers should aim to communicate their findings to a wider

audience so that they can also benefit from the new knowledge.

-

1 1 8 -

7.

Researchers should attempt to relate any new knowledge or understanding they

gain to both their own personal theories and to published theories so that the

former can be evaluated in terms of its wider conceptual and theoretical

context.

(adapted from Bassey, 1990, p. 35)

Like Bassey, we believe that this set of ground rules is fundamental to any kind of inquiry.

Figure 1. Action research in action (Kemmis and McTaggart, 1981, p.

14, reprinted in Hopkins, 1985, p. 55).

1.4. ETHICS AND PRACTITIONER RESEARCH

Strangely enough, Bassey does not mention taking ethical considerations into account, although

these are of paramount importance. As Nias points out:

…Enquiry-based courses… have far-reaching implications for teachers, schools

and providing institutions and for the relationships between them. For a student,

to subject professional practice (be it one's own or that of others) to systematic

enquiry and to share the results of this scrutiny with a wider audience than simply

a course tutor is to open oneself and one's colleagues to self-doubt and criticism…

-

1 1 9 -

Schools too may be opened up to more examination than many of their members

want and, as a result, internal differences and divisions may be exacerbated.

(Nias, 1988, p. 10)

Sound ethical practices should be observed whatever kind of research one is engaged in. As Nias

points out, many sensitive issues can arise as a result of practitioners carrying out research into their own

institutional context. Making sure that ethical procedures are carefully followed may not completely

resolve problems, but will certainly show others that you are aware of your responsibilities and the

potential consequences of your enquiry. Each of the sections which follow contains advice on ethical

procedures which are specific to the methods they describe. The following is a more general list.

Eth ics for practitioner research

Observe protocol: Take care to ensure that the relevant persons, committees and

authorities have been consulted, informed and that the necessary permission and

approval have been obtained.

Involve participants: Encourage others who have a stake in the improvement

you envisage to shape the form of the work.

Negotiate with those affected: Not everyone will want to be directly involved;

your work should take account of the responsibilities and wishes of others.

Report progress: Keep the work visible and remain open to suggestions so that

unforeseen and unseen ramifications can be taken account of; colleagues must

have the opportunity to lodge a protest with you.

Obtain explicit authorization before you observe: For the purposes of

recording the activities of professional colleagues or others (the observation of

your own students falls outside this imperative provided that your aim is the

improvement of teaching and learning).

Obtain explicit authorization before you examine files, correspondence or

other documentation: Take copies only if specific authority to do this is

obtained.

Negotiate descriptions of people's work: Always allow those described to

challenge your accounts on the grounds of fairness, relevance and accuracy.

Negotiate accounts of others' points of view (e.g., in accounts of

communication): Always allow those involved in interviews, meetings and

written exchanges to require amendments which enhance fairness, relevance and

accuracy.

Obtain explicit authorization before using quotations: Verbatim transcripts,

attributed observations, excerpts of audio- and video-recordings, judgements,

conclusions or recommendations in reports (written or to meetings) [for advice on

quotations from published materials, see Section 6].

Negotiate reports for various levels of release: Remember that different

audiences demand different kinds of reports; what is appropriate for an informal

verbal report to a [staff] meeting may not be appropriate for a ... report to council,

a journal article, a newspaper, a newsletter to parents; be conservative if you

cannot control distribution.

Accept responsibility for maintaining confidentiality.

Retain the right to report your work: Provided that those involved are satisfied

with the fairness, accuracy and relevance of accounts which pertain to them; and

that the accounts do not unnecessarily expose or embarrass those involved; then

accounts should not be subject to veto or be sheltered by prohibitions of

confidentiality.

-

1 2 0 -

Make your principles of procedure binding and known: All of the people

involved in your … research project must agree to the principles before the work

begins; others must be aware of their rights in the process.

(Kemmis and McTaggart, 1981, pp. 43-4, reprinted in Hopkins, 1985, pp. 135-6)

1.5. THEORY AND EVIDENCE IN PRACTITIONER

RESEARCH

Now that we have established a set of ground rules and a set of ethical principles it is time to go

on to consider the relationship between theory and evidence in practitioner research. Bassey mentions the

importance of relating research to theory in his rules 3 and 7, where he makes the distinction between

'personal' and 'published' theories.

THEORIES

There is nothing mysterious about a theory. People devise theories to explain observable

relationships between events or sets of events. Traditional scientific theories offer explanations in terms

of causal relationships between events and/or behaviours. Once a theory has been formulated it can be

used to predict the likely outcome when similar sets of circumstances occur. Testing whether these

predictions are correct or not is one way of testing the theory itself. A theory is, then, a coherent set of

assumptions which attempts to explain or predict something about the behaviour of things and events in

the world. A physicist might have a theory which can predict the behaviour of subatomic particles under

certain conditions; an historian might have a theory about the causes of the Industrial Revolution; and an

educational psychologist a theory about the causes of underachievement in inner-city schools. In all these

cases, the theories held by the physicist, historian and psychologist are likely to have been derived from

published accounts of previous research. They might also have personal theories, based on their own

experiences, beliefs and observations. Often what attracts people to one published theory rather than

another is its close match with their own personal ideas and assumptions.

For example, take the commonly held idea that practical experiences enhance and consolidate

children's learning. This idea (or hypothesis) stems from the published theories of the Swiss psychologist

Jean Piaget. Piaget's ideas became popular through documents such as the Plowden Report (Central

Advisory Council for Education, 1967) and the Cockcroft Report (DES, 1982) and are reflected today in

recommendations put forward in various national curriculum documents. For example, attainment target 1

– exploration of science – reads as follows:

Pupils should develop the intellectual and practical skills that allow them to

explore the world of science and to develop a fuller understanding of scientific

phenomena and the procedures of scientific exploration and investigation.

(DES, 1989, p. 3)

In a published account of her work, Virgina Winter explains how this idea, coupled with her own

belief that science teaching should emphasize 'practical, investigative and problem-solving activities', led

her to undertake a systematic appraisal of the science work offered in her school (Winter, 1990, p. 155).

She was particularly interested in the ways in which her pupils acquired 'process skills', that is the

practical skills necessary for them to carry out controlled scientific experiments. She also wanted to find

out about children's perceptions of science, and whether they understood the way scientists worked. In

this example, you can see how public and personal theories can come together to act as a stimulus for a

piece of research.

EVIDENCE AND DATA

In order to compare two rival theories, one needs to gather evidence. It is worth remembering that

showing a theory is incorrect is more important than simply confirming it. In science, falsifying theories

and setting up and testing alternative theories is the principal means of advancing knowledge and

understanding. This is also the case in educational research. As an example of this, let's take a closer look

at Virginia Winter's research.