Perrie M. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

nancy shields kollmann

Society interacted with law in a multitude of ways in seventeenth-century

Muscovy. Traditional distributive justice shaped adjudication; the multiplic-

ity of norms and venues undermined judicial consistency. But the trend was

nevertheless towards a greater rationalisation. Codification was proceeding,

standardised norms of record-keeping were being established; standards of

evidence favoured rational proof. Scholars have deemed these trends ‘abso-

lutist’. So also might one term the concept of ‘the common good’ that appears

in the law by the end of the century. The concept that the state uses law

to serve the public good came to court circles from Ukraine by the 1680s

and inspired many of the projects of military and bureaucratic reform of that

decade. Despite its complexity, seventeenth-century law provided Peter the

Great with a firm foundation when he launched his bold effort to standardise

law and administration on the ‘well-ordered police state’ model in the next

century.

578

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

25

Urban developments

denis j. b. shaw

The seventeenth century was a difficult period for Russia, as it appears to have

been for much of Europe. Yet this is a very broad generalisation, difficult to

substantiate from the limited evidence and paying scant heed to geographical

and chronological differences. After 1613 Russia was able to enjoy the benefits

of a stable dynasty, a situation in marked contrast to the anarchic times which

went before. And it was a realm still undergoing vigorous expansion and

colonisation. Such discordant processes were naturally reflected in the life

of Russia’s towns. Fortunately the sources which permit the study of urban

developmentsarericher andfuller forthis period than theyareforthe sixteenth

century and they have been better explored by historians. But they are all

too often sporadic and uneven, and their meaning sometimes obscure. This

chapter will consider a number of facets of urbanism in the period. It will

also address two issues, namely the symbolic and religious role of towns

and their physical morphology, which do not figure in Chapter 13 on the

sixteenth century but which can be profitably studied for both periods taken

together.

The urban network

As was the case in the sixteenth century, the legal status of towns in the seven-

teenth remained uncertain and the places referred to as ‘towns’ (goroda) in the

sources were often fortresses with little or no commercial function, or some-

times they did have a trading function but lacked a posad population.

1

Some

‘towns’ even had no subsidiary district (uezd), such as the three gorodki (literally,

‘little towns’) of Kostensk, Orlov and Belokolodsk built on the Belgorod Line

near Voronezh in the middle of the century or, it appears, the nearby private

1 That is, a tax-bearing population attached to a legal commercial suburb. Conversely,

other towns had a legal posad but lacked commercial activity.

579

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

denisj.b.shaw

town of Romanov whichbelonged to the tsar’skinsman,boyarN.I. Romanov.

2

Equally other places, like the monastic settlement of Tikhvin Posad towards

the north-west, had commercial functions but were not referred to as towns.

Adopting a catholic definition of the term, French has argued that there were

around 220 towns in Russia at the beginning of a century which witnessed

the appearance of about a hundred new ones during its course.

3

Vodarskii,

however, argued for a stricter, Marxist definition of a town as a place having

both a legal commercial suburb (posad) and a commercial function. On this

basis he recognised 160 towns in 1652, rising to 173 in 1678 and 189 by 1722.

4

The appearance of many new towns in Russia during the course of the

seventeenth century is largely explained by the process of frontier expansion

and colonisation of new territories. In the west many towns were acquired

as the state expanded its frontiers in that direction. To the east numerous

new towns were built as the Russian state took control of more and more of

Siberia. The first Russian town on the Pacific, Okhotsk, was founded in 1649.

Many Siberian towns remained quite small, however. Thus Vodarskii names

nineteen principal administrative centres in Siberia for 1699, only thirteen of

which were towns by his definition. According to his figures, at the end of the

century Siberia had a total of only 2,535 posad households.

5

More significant in

terms of town founding was Russia’s southern frontier west of the Urals. Here

a concerted effort was made from the 1630sto1650s to set up a series of forti-

fied towns along and behind the new Belgorod and Simbirsk military lines.

6

Subsequently, in the second half of the century, many new towns appeared in

the forest-steppe and steppe south and east of these lines.

A number of studies have been made of the broad population data for

towns, using the rather richer sources which are available for this period.

7

2 V. P. Zagorovskii, Belgorodskaia cherta (Voronezh: Izdatel’stvo Voronezhskogo univer-

siteta, 1969), pp. 211, 227–9.

3 R. A. French, ‘The Early and Medieval Russian Town’, in J. H. Bater and R. A. French

(eds.), Studies in Russian Historical Geography (London: Academic Press, 1983), pp. 249–77;

R. A. French, ‘The Urban Network of Later Medieval Russia’, in Geographical Studies on

the Soviet Union: Essays in Honor of Chauncy D. Harris (Chicago: University of Chicago,

Department of Geography, Research Paper no. 211, 1984), pp. 29–51.

4 Ia. E. Vodarskii, Naselenie Rossii v kontse XVII v–nachale XVIII v. (Moscow: Nauka, 1977),

p. 133.

5 Ibid., p. 127; Ia. E. Vodarskii, ‘Chislennost’ i razmeshchenie posadskogo naseleniia v Rossii

vo vtoroi polovine XVII v.’, in Goroda feodal’noi Rossii (Moscow: Nauka, 1966), p. 290.

6 D. J. B. Shaw, ‘Southern Frontiers of Muscovy, 1550–1700’, in Bater and French, Studies,

pp. 117–42.

7 P. P. Smirnov, Goroda Moskovskogo gosudarstva v pervoi polovine XVII veke, vol. i, pt. 2 (Kiev:

A. I. Grossman, 1919); Vodarskii, ‘Chislennost’ ’; Henry L. Eaton, ‘Decline and Recovery

of the Russian Cities from 1500 to 1700’,CASS11 (1977): 220–52.

580

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Urban developments

The latter include cadastral surveys, census books and associated enumera-

tions which provide statistics on numbers of posad households, most notably

in censuses of 1646–7 and 1678–9. Additionally there are enumerations dat-

ing from 1649–52 which record the households of traders and handicrafts

people, many in ‘white places’,

8

which were added to the posady of towns

as a result of the 1649 Legislative Commission (see below). Also important

are enumerations of military servitors and ‘able-bodied’ personnel under-

taken for towns in various years, usually under the auspices of the Military

Chancellery (Razriadnyi prikaz). Most notable among these is a military cen-

sus for 1678.

9

Vodarskii has provided urban household data for 212 towns

(plus Siberian towns taken together) for 1630–50, 1670–80 and 1722 based on

Smirnov’s data for 1646–7 and 1649–52 and on his own analyses for the later

dates.

10

Figure 25.1 reproduces his data for towns having 500 or more posad

households in the seventeenth century. His data for 1722 are omitted. For

comparison the table also lists numbers of posad households recorded for the

latter part of the sixteenth century where available, based on the study by

Eaton.

11

The data are too uncertain and too scanty to allow solid conclusions to

be drawn about urban growth trends, though perhaps the apparent sharp

fall in the size of the posad in some commercial centres (Kaluga, Nizhnii

Novgorod, Novgorod, Suzdal’) between the late sixteenth century and the

1640s is worthy of note. Moscow was clearly dominant, as in the previous

century, although once again the sources are sparse.

12

In addition to Moscow,

the largest towns, with over 1,000 posad households (Vologda, Kazan’, Kaluga,

Kostroma, Nizhnii Novgorod, Iaroslavl’) were all old towns which dated from

before the sixteenth century and, apart from Kazan’, all having a long history

of connection with Muscovy. They were all situated on major river and trading

routes. The fall of Novgorod from this group over the previous century no

doubt reflects the troubles of the latter half of the sixteenth century and the

early seventeenth, together with the problems of accessing the Baltic (see

Chapter 13). The disappearance of Smolensk is also significant, connected to

its loss to Poland down to the middle years of the century. The wars with

8 ‘White places’ were parts of towns which were free of the normal tax and service

obligations.

9 DopAI, vol. ix (St Petersburg: Tipografiia II Otdeleniia Sobstvennoi E. I. V. Kantseliarii,

1875), no. 106,pp.219–314.

10 Vodarskii, ‘Chislennost’ ’, pp. 282–90; Smirnov, Goroda,pp.32ff.

11 Eaton, ‘Decline and Recovery’, pp. 235–46.

12 Ibid., pp. 250–1.

581

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

denisj.b.shaw

Town 12 3 45 678

Archangel and Kholmogory 645 1,018 263 715 835 4 138

Arzamas 430 2 135 559 560 — 98

Balakhna 637 — 112 661 642 9 140

Galich 729 (41) 46 788 481 19 46

Iaroslavl’ 259

a

2,871 174 564 3,042 2,310 57 468

Kaluga 723 588 339 105 694 1,015 — 45

Kargopol’ and 476 538 20 6 — 666 ——

Turchasov

Kazan’ 598 1,191 1,600 200 — 310 ——

Khlynov 247 624 1 26 661 616 20 142

Kolomna 34 615 8 261 740 352 — 79

Kostroma 1,726 54 414 2,086 1,069 — 106

Kursk 270 396 20 — 538 104 11

Moscow 1,221

b

(20,000)

b

8,000

b

3,615 7,043

c

——

Nizhnii Novgorod 2421

a

1,107 500 666 1,874 1,270 — 600

Novgorod 4157 640 1,050 145 770 862 153 344

Olonets 376 ——155 155 637 ——

Pereslavl’-Zalesskii 525 (80) 104 624 408 — 110

Pskov 940 (1,306) 51 997 912 372 1,043

Rostov 16

a

416 (15) 167 552 491 — 217

Simbirsk — — — 19 504 — 114

Sol’ Kamskaia 549 9 146 686 831 25 20

Suzdal’ 414 360 (14) 495 435 519 7 596

Torzhok 89

a

486 8 58 508 659 ——

Tver’ 345 53 250 497 524 — 110

Uglich 447 — 226 603 548 — 49

Ustiug Velikii 744 53 36 — 920 — 119

Vladimir 483 58 405 703 400 — 290

Vologda 591 1,234 175 363 1,674 1,196 13 284

Zaraisk 446 (127) 65 587 254 — 1

Key:1. Posad households,c.1550–1590s; 2. Posad households,1646; 3. Servitor households,

1650 (figures in parentheses – 1632); 4. Other households, 1646; 5. Posad households,

1652; 6. Posad households, 1678; 7. Servitor households, 1670s (partial data); 8. Other

households, 1678 (partial data).

a. Data for 1610s

b. Data for 1638

c. Data for 1700

Sources: Henry L. Eaton, ‘Decline and recovery of the Russian cities from 1500 to 1700’,

Canadian-American Slavic Studies 11 no. 2 (1977): 220–52; Ia. E. Vodarskii, ‘Chislennost’

i razmeshchenie posadskogo naseleniia v Rossii vo vtoroi polovine XVIIv.’, in Goroda

feodal’noi Rossii (Moscow, 1966), pp. 271–97.

Figure 25.1. Urban household totals in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (towns

with 500 or more households in the posad in the seventeenth century)

582

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Urban developments

Poland badly affected Russo-Polish trade, which did not in fact recover until

after about 1750.

13

Eaton has ascribed the apparent fall in the size of the posad in some of the

biggest towns (Vologda, Kazan’, Kostroma, Nizhnii Novgorod and Iaroslavl’)

between 1652 and 1678 to general lack of economic buoyancy in the latter half

of the century compared to the apparent recovery in the first half. He thus

questions those Soviet scholars whotook a more optimistic view, regarding the

century as the time when the ‘all-Russian market’ appeared, following Lenin’s

dictum. It may be that Vodarskii exaggerated the overall growth in the total

number of posad dwellers in Russia between the two dates, although numbers

do seem to have grown absolutely. The sluggish growth or even stagnation

of some of the older towns in central Muscovy was probably offset by greater

economic vigour on some of the frontiers.

14

The official posad dwellers were, of course, by no means the only residents

of Russian towns in the seventeenth century. According to Vodarskii, they

constituted only 34 per cent of the total urban population in 1646, 44 per cent

in 1652 (after the addition of the ‘white places’), and 41 per cent in 1678.Of

greater numerical significance were the state servitors or military personnel

who formed 53 per cent in 1652 and 45 per cent by 1678.

15

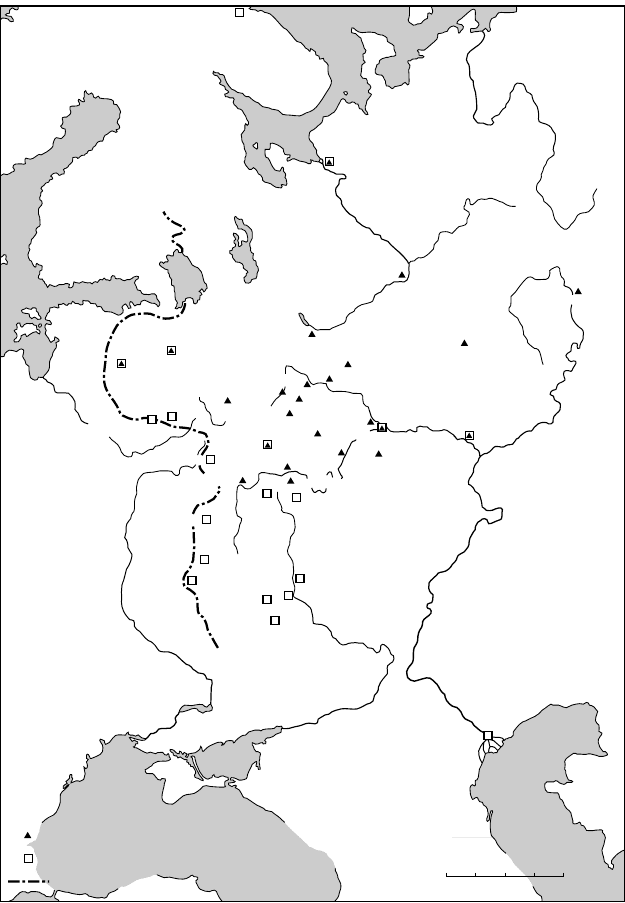

Figure 25.1, which

shows only the towns with 500 posad households or more, omits some of those

with really big urban garrisons. Belgorod, for example, recorded only 44 posad

households in 1646 but 459 servitor households in 1650. Kursk recorded 270 and

396 respectively, Sevsk none and 6,017, Voronezh 85 and 1,135, and Astrakhan’

none and 3,350.

16

Servitors often engaged in trade and craft activity, especially

before 1649, though many were paid and others lived by agrarian pursuits,

particularly in the south. In the 1640s the bigger urban garrisons were clearly

locatedin Moscow, alongthe vulnerablewestern and southernfrontiers, and at

three strategic points on the Volga (Nizhnii Novgorod, Kazan’ and Astrakhan’)

(see Map 25.1).

In addition to the posad dwellers and military personnel, towns had other

elements in their populations, not all of whom were recorded in the various

censuses. Depending on the size and location of the town, these would include

state officials and higher or middle-ranking servitors, their dependents, clergy

and their dependents, cottars (bobyli), peasants, beggars and other unofficial

13 PaulBushkovitch,The MerchantsofMoscow, 1580–1650(Cambridge:Cambridge University

Press, 1980), pp. 87–91.

14 J. Pallot and D. J. B. Shaw, Landscape and Settlement in Romanov Russia, 1613–1917 (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1990), pp. 241–64, esp. 242–4, and also 308–9.

15 Vodarskii, ‘Chislennost’ ’, p. 279.

16 Ibid., pp. 282–90.

583

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

denisj.b.shaw

0 400 km200

Archangel

(and Kholmogory)

Kol’skii Ostrog

N

o

r

t

h

e

r

n

D

v

i

n

a

Ustiug Velikii

Khlynov

Sol’ Kamskaia

Kazan’

Arzamas

V

o

l

g

a

Nizhnii

Novgorod

Galich

Kostroma

Rostov

Balakhna

Vladimir

Murom

Zaraisk

Mikhailov

Tula

Voronezh

Don

Korotoiak

Valuiki

Sevsk

Putivl’

Iablonov

Briansk

Kaluga

Viaz’ma

Kolomna

Moscow

Velikie Luki

Toropets

Pskov

Novgorod

Torzhok

Uglich

Iaroslavl’

Vologda

Oka

Astrakhan’

Pereslavl’-

Zalesskii

Towns with 500 or more

posad

households (1652)

Towns with 500 or more servitor households (1650)

Western frontier

D

n

i

e

p

e

r

Map 25.1. Towns in mid-seventeenth-century European Russia

584

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Urban developments

groups, and sometimes foreigners and non-Russian peoples. To measure the

level of urbanisation in Russia by considering only the proportion of the total

population who were posad dwellers (a legal rather than an occupational or

social category) is therefore quite misleading.

17

Russian towns of this period have often been described as static with little

commercialvivacityand, at best,sluggish ingrowth.Thereis sometruthinthis

picture for, as we have noted already, the seventeenth century was a difficult

period. Sluggishness in a demographic sense, however, was a normal charac-

teristic of early modern (pre-industrial) towns all over Europe.

18

Furthermore

such assessments often overlook a most important feature of Russian towns

in this period – their significance not as individual places but in the broader

urban network which was developing across the Russian state. In other words

towns had a pivotal role in the building of the state, acting as co-ordinating

points for all kinds of activities which helped bind the state together. It is in

this sense that de Vries talks of ‘structural urbanisation’.

19

It is this issue which

forms the focus of the rest of this chapter.

Urban society and administration

The establishment of the Romanov dynasty in 1613 was quickly followed by

moves to pacify and control the extensive territories of the state. Towns played

a significant role in this process. Towns had long been regarded as admin-

istrative centres for their surrounding districts or uezdy. This function was

now strengthened as the office of voevoda, or military governor, which was an

appointment of the central government, was now extended from the frontier

regions to central and northern towns. The voevoda was now the tsar’s rep-

resentative in the locality, charged with upholding the state’s interests and

overseeing both military and civil matters within his area of jurisdiction.

In these tasks he was aided by a small bureaucracy of officials centred in

the governor’s office (prikaznaia izba). Nowhere perhaps was the voevoda’s

function more apparent than on the vulnerable southern frontier where the

entire defensive and civilian life of each town and its district was meant to be

17 See Vodarskii, Naselenie,pp.129–34. On the basis of Vodarskii’s data, the ‘urban’ popula-

tion in 1678 (posad dwellers plus other urban residents – nobility, administration, clergy,

housekeepers and others) can be estimated at around 4 per cent of the total. However,

this does not appear to include the servitors, or the elements (peasants and others) who

resided in towns illegally. The data excludes Ukraine.

18 J. de Vries, European Urbanization, 1500–1800 (London: Methuen, 1984), pp. 254–8.

19 Ibid., p. 12.

585

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

denisj.b.shaw

organised by the voevoda with the strictest eye on security.

20

It was also on

the frontier that the closer co-ordination of the town’s functions as nodes in

the state’s military and administrative structures at local level was pioneered.

Here the founding and development of each town, and its subsequent life

and defensive role, was the immediate concern of the Military Chancellery

in Moscow. By the middle of the century that chancellery was attempting to

improve defensive co-ordination between the towns by designating military

districts (razriady) under the jurisdiction of one central town. The first per-

manent one was established in the 1640s and 1650s centred on Belgorod. This

was followed by other frontier districts (Sevsk, Smolensk, Novgorod, Kazan’,

Tambov) and, in the last quarter of the century, by some in the country’s inte-

rior (Moscow, Vladimir, Riazan’). This move was clearly a harbinger of Peter

the Great’s provincial reform in the early eighteenth century and was moti-

vated by some of the same goals – to improve control and co-ordination over

localities.

21

The office of voevoda, characterised by a continual tendency to interfere in

local affairs and not a little corruption, rarely sat well with the felt interests

of urban communities or with the functions of locally elected officials like

the police elders (gubnye starosty) and land elders (zemskie starosty)whowere

invested with the responsibility of carrying out certain key functions on behalf

of the state. As has been remarked so often, the latter’s elected status did not

imply any real measure of urban autonomy. But numerous tensions arose

out of the primitive character of the system of administration as well as from

the conflicting nature of the state’s goals – for example, between the need to

raise as much revenue as possible from the towns, on the one hand, and the

desire to foster urban trade and commerce on the other. Most towns, except

the smaller frontier forts, were multifunctional, but the different functions

were not always easily reconcilable.

The fragmented character of urban society which characterised sixteenth-

century towns continued to be a feature of the seventeenth. However, as

explainedin Chapter23,the situation was somewhat simplified bythe Ulozhenie

of 1649 which abolished the ‘white’(tax privileged) status of many ecclesiastical

and private suburbs and added them to the posad. According to Vodarskii’s cal-

culations, the total number of male posad dwellers in Russian towns rose from

about 83,000 in 1646 to some 108,000 in 1652, a rise very largelyaccounted for by

the effects of the Ulozhenie. The great majority of the households confiscated

20 Pallot and Shaw, Landscape,pp.23–4.

21 Ibid., p. 246.

586

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Urban developments

by the state in 1649 were in fact Church and monastic ones.

22

There had long

been resentment on the part of the ‘black’ posad dwellers over commercial

competition from their more privileged neighbours in the ‘white’ suburbs,

and the 1649 reform was stimulated by a series of urban riots over this and

other issues the previous year. However, another effect of the reform was to

strengthen the attachment of the posad dweller to the posad where he lived.

Henceforth the posad dweller was to stay put and share the burden of taxation

and service laid upon the posad community as a whole by the government.

He was not to move elsewhere, even if superior commercial opportunities

seemed to warrant it. Similarly, those posad traders who were discovered to be

living in non-urban centres (often engaged in trade there) were to be returned

to their own posad, whilst no posad dweller was to ‘commend’ himself (sell

himself into slavery, usually by reason of debt) to a wealthy landowner or to

the Church.

23

In this way not only was the posad consolidated as a source of

revenue for the state but its role as a co-ordinator of the commercial life of the

country was strengthened.

Urban commerce

We have seen that the 1649 Ulozhenie abolished the ‘white places’, added their

inhabitants to the ranks of the ‘black’ posad dwellers and tied the latter to the

posad byforbiddingmigration. It also had a numberof other implications.Thus

article 6 of chapter 19 (the chapter dealing with the townspeople) orders any

agricultural peasants from hereditary or service estates who have shops, ware-

houses or salt boilers in Moscow or other towns to sell them to members of the

posad community and return to their estates. ‘Henceforth no one other than

the sovereign’s taxpayers shall keep shops,warehouses and salt boilers.’

24

Thus

the posad community was guaranteed a virtual monopoly over urban trade.

This monopoly was constrained by two exceptions. Firstly, article 11 permit-

ted the minor servitors of provincial towns, namely musketeers, cossacks and

dragoons who were engaged in commercial enterprises and kept shops to con-

tinue with those activities provided they paid customs duties and the annual

shop tax. Since, however, they were not members of the posad community

but engaged in the tsar’s service, they were freed from other urban taxes and

22 P. P. Smirnov, Posadskie liudi i ikh klassovaia bor’ba do serediny XVII v., 2 vols. (Moscow and

Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1947–8), vol. ii,pp.701–18.

23 R. Hellie (ed. and trans.), The Muscovite Law Code (Ulozhenie) of 1649, pt. 1: Text and

Translation (Irvine, Calif.: Charles Schlacks, 1988), ch. 19,art.9, 13,pp.154–5 (hereafter

Hellie, Ulozhenie).

24 Ibid., p. 153.

587

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008