Perrie M. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

martin dimnik

Moreover, the ‘Life’ (Zhitie) of Avramii of Smolensk provides valuable data on

the social conditions of the time.

35

Two genealogical considerations were pivotal for Rostislav’s successful

occupation of Kiev: after the death of his brother Iziaslav he became the

eldest surviving Mstislavich; and after the death of his uncle Iurii he became

the eldest prince in the entire House of Monomakh. He was therefore the

legitimate claimant from both camps. Since all the princes in the House of

Monomakhaccepted his candidacy,hisreignwitnessed fewerinternecinewars.

The Polovtsy, however, intensified their attacks. They raided caravans travel-

ling by river and by land from the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov regions.

Rostislav organised campaigns against the nomads but failed to curb their

forays.

He died on 14 March 1167.

36

After that, the Mstislavichi split into two

dynasties: the one in Volyn’ descended from Iziaslav who had made that

region his family possession, and the one in Smolensk descended from Ros-

tislav.

37

(See Table 5.4: The House of Volyn’, and Table 5.5: The House of

Smolensk.) Following the latter’s death, his nephew Mstislav Iziaslavich of

Vladimir-in-Volynia pre-empted the right of his uncle Vladimir Mstislavich

of Dorogobuzh to rule Kiev.

38

At first, Mstislav had the support of the other Mstislavichi because they

expected to manipulate him. They discovered that he was no man’s lackey,

however, after he refused to grant them the towns they demanded. He also

antagonised Andrei Bogoliubskii, who had replaced his father Iurii Dolgorukii

in Suzdalia. Andrei saw Mstislav’s accession as a violation of the traditional

order of succession to Kiev. Moreover, Mstislav appointed his son Roman to

Novgorod, whereAndrei was seekingto asserthis influence. Despite Mstislav’s

unpopularity, he successfullyassembled the princes of Rus’against the Polovtsy.

While in the field, however, he antagonised them further. Without informing

them, he allowed his men to plunder the camps of the nomads. After that, we

are told, the princes plotted against him.

39

35 On Smolensk, see L. V. Alekseev, Smolenskaia zemlia v IX–XIII vv. Ocherki istorii Smolen-

shchiny i Vostochnoi Belorussii (Moscow: Nauka, 1980). For Rostislav’s charter, see Ia. N.

Shchapov, Kniazheskie ustavy i tserkov’ v drevnei Rusi XI–XIV vv. (Moscow: Nauka, 1972),

pp. 136–50. For Avramii, see P. Hollingsworth (trans. and intro.), The Hagiography of Kievan

Rus’ (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992), pp. lxix–lxxx.

36 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 528–32.

37 For Rostislav’s descendants, see Baumgarten, G

´

en

´

ealogies et mariages,tableix.

38 PSRL, vol. ii, col. 535. For Vladimir and Mstislav, see Baumgarten, G

´

en

´

ealogies et mariages,

table v, 30 and 36.

39 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 538–43.

108

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Rus’ principalities (1125–1246)

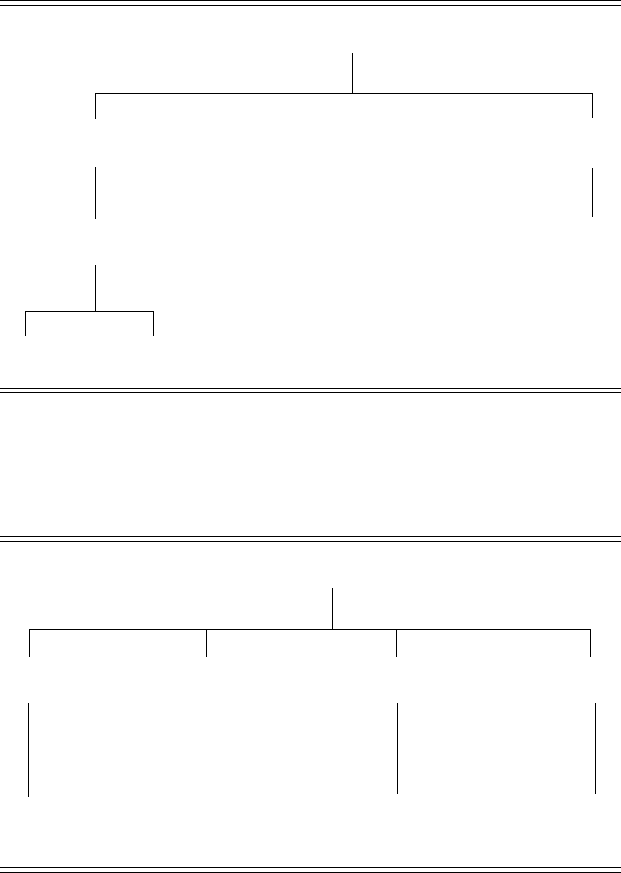

Table 5.4.

The House of Volyn’

Iziaslav

d. 1154

Mstislav

d. 1172

Iaroslav

d. 1180

Roman

d. 1205

Ingvar’

d. 1212

Daniil

d. 1264

Vasil’ko

d. 1269

Table 5.5. The House of Smolensk

Rostislav

d. 1167

Roman

d. 1180

David

d. 1197

Riurik

d. 1208

Mstislav

d. 1180

Mstislav

d. 1223

Vladimir

d. 1239

Mstislav

the Bold

d. 1228

109

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

martin dimnik

Andrei Bogoliubskii

In 1169 Andrei Bogoliubskii organised a coalition to evict Mstislav from Kiev.

Princes from Suzdalia, Smolensk, Volyn’ and Chernigov joined the campaign

led by Andrei’s son Mstislav.

40

Many took part not only because they acknowl-

edged Andrei’s prior claim to Kiev, but also because they resented Mstislav for

cheating them out of booty. Historians are not agreed on Andrei’s objective

in attacking Kiev or on the significance of its capture on 8 March. Some claim

that his aim was to recover the Kievan throne for the rightful Monomashichi

claimants because Kievwas the capital of the land. Others, however, argue that

Andrei attempted to subordinate it to Vladimir and that its capture signalled

its decline.

41

Perhaps there is an element of truth in each view. In forcing the usurper

Mstislav to flee to Volyn’, Andrei, the rightful claimant for the House of

Suzdalia, was able to seize control of Kiev. Surprisingly, afterhis forcescaptured

the town, they sacked it.

42

Their action obviously did not penalise Mstislav in

any way. Rather, the attackers vented their spleen against the Kievans. They

seemingly ransacked the capital out of envy for its prosperity and out of fury

at the arrogance of its citizens. Andrei, of course, had his own reason for

condoning the pillaging. He wished to see Kiev wane in magnificence because

he was striving to build up his capital of Vladimir as its rival. But his scheme

failed. The plundering did not lead to Kiev’sdecline. Itrecoveredand flourished

to suffer even more debilitating sacks in 1203 and in 1240. The evidence that

the dynasties which were eligible to rule it continued to covet it as the most

cherished plum in Rus’ testifies to its continued prosperity.

Meanwhile, Novgorod also remained a bone of contention. Since Suzdalia

served as the conduit through which Baltic trade passed from Novgorod to the

Caspian Sea, Andrei sought to wrest control of the town from the prince of

Kiev and assert his jurisdiction over it. Two years after expelling Mstislav from

Kiev, he finally forced the Novgorodians to capitulate by laying an embargo

on all grain shipments to their town.

43

Although historians disagree on Andrei’s objectives and achievements, it is

safe to assert that he defended the order of succession to Kiev championed

40 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 543–4.

41 Historians do not agree whether or not Kiev lost its pre-eminence in Rus’ after Andrei’s

alliance sacked it. Forthe discussions, see P. P. Tolochko, Drevniaia Rus’, Ocherki sotsial’no-

politicheskoi istorii (Kiev: Naukova Dumka, 1987), pp. 138–42; Franklin and Shepard, The

Emergence of Rus,pp.323–4; Fennell, Crisis,p.6.

42 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 544–5.

43 Novgorodskaia pervaia letopis’,pp.221–2.

110

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Rus’ principalities (1125–1246)

by his father. Unlike Iurii, however, he chose to live in Suzdalia. The fate of

his father was one deterrent. Moreover, if he occupied Kiev he would remove

himself dangerously far from his centre of power in Suzdalia. As Iaroslav the

Wise had foreseen, a prince whose patrimony abutted on Kiev had the best

chance of ruling it successfully because he could summon auxiliary forces

quickly from his patrimony. Nevertheless, realising that ruling Kiev gave its

prince a great moral advantage, Andrei could not allow it to fall into a rival’s

hands. Adhering to the system of genealogical seniority, he gave it to his

younger brothers, who also had the right to sit on the throne of their father.

First, he sent GlebfromPereiaslavl’, but the Kievans poisoned him,orsoAndrei

believed. Gleb’s alleged murder would have confirmed Andrei’s suspicion that

the Kievans despised the sons just as vehemently as they had hated Iurii. Next,

he appointed Mikhalko. But the latter declined the dubious honour by handing

over the town to his brother Vsevolod.

44

AfterMstislav Iziaslavich died in Volyn’ in 1170, the Rostislavichi of Smolensk

took up the battle for Kiev. They evicted Vsevolod and gave the town to Riurik

Rostislavich.

45

Three years later, Andrei formed a coalition with Sviatoslav

Vsevolodovich of Chernigov. He was determined to avenge Gleb’s death and

to punish the Rostislavichi for their insubordination by expelling Riurik. Svi-

atoslav, for his part, intended to occupy Kiev. Thus, Andrei conceded that

Sviatoslav’s claim to the capital was as legitimate as his was. He also tacitly

admitted his failure to maintain puppets in Kiev. Sviatoslav, the commander-in-

chief of the coalition, evicted Riurik and occupied the town. Later, however,

Iaroslav Iziaslavich of Lutsk, the younger brother of the deceased Mstislav,

brought reinforcements from Volyn’, helped Riurik to expel Sviatoslav, and

occupied Kiev.

46

In his patrimony, one of Andrei’s main objectives was to raise the political,

economic, cultural and ecclesiastical status of Vladimir above that of Kiev.

Accordingly, hecompleted his father’sbuilding projects and initiated newones.

He built the Assumption cathedral in Vladimir, its Golden Gates in imitation

of those in Kiev, his court at the nearby village of Bogoliubovo (from which

he received the sobriquet Bogoliubskii), and the church of the Intercession of

Our Lady on the River Nerl. Since he hired artisans from all lands, his churches

reflected Romanesque, Byzantine and Trans-Caucasian styles. In striving to

create an aura of holiness in Vladimir, he enshrined the relics of Bishop Leontii

of Rostov and brought the so-called Vladimir icon of the Mother of God from

44 PSRL,vol.ii, cols. 569–70.

45 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 570–1.

46 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 572–8.

111

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

martin dimnik

Vyshgorod. Hoping to equate the Christian heritage of his capital with that

of Kiev, he propagated the pious myth that St Vladimir founded Vladimir. He

also attempted, in vain, to create a new metropolitan see.

Andrei adopted autocratic practices in relation to his neighbours. He

expanded his domains into the lands of the Volga Bulgars and imposed his

will over the princes of Murom and Riazan’. At home he sought to undermine

the authority of his subjects in their local assembly (veche); he expelled three

of his brothers, two nephews and his father’s senior boyars; and he spurned

the magnates of Rostov and Suzdal’ by making the smaller town of Vladimir

his capital. After that the region was also referred to as Vladimir-Suzdal’. His

overbearing policies evoked great resentment. Finally, on 29 June 1174, while he

was waiting for Sviatoslav Vsevolodovichin Chernigov to approve his appoint-

ment of Roman Rostislavich of Smolensk to Kiev, his boyars assassinated

him.

47

Sviatoslav Vsevolodovich

After that, Sviatoslav acted as kingmaker in Vladimir-Suzdal’. Earlier, after

Andrei had evicted his brothers and nephews from Suzdalia, Sviatoslav had

given them sanctuary in Chernigov. Following Andrei’s death he helped

the refugees to fight for their inheritance. After a bitter rivalry between

theuncles and the nephews, Vsevolod,later tobe knownas ‘BigNest’ (Bol’shoe

Gnezdo) because of his many offspring, seized Vladimir on the Kliaz’ma.

48

He was indebted for his success, in part, to Sviatoslav’s backing. He would

rule Vladimir for almost forty years and become the most powerful prince in

the land.

After Andrei’s death, Roman, the senior prince of the Rostislavichi, replaced

Iaroslav Iziaslavich in Kiev.

49

In 1176, however, Sviatoslav found a pretext for

attacking Roman with the Polovtsy. Not wishing to expose the Christians of

Rus’ to carnage, Roman ceded control of the town to Sviatoslav.

50

Soon after,

the Novgorodians invited the latter to send his son to them.

In the meantime, to strengthen the power of his son-in-law Roman

Glebovich of Riazan’ against Vsevolod Big Nest, Sviatoslav sent troops

47 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 580–95. Concerning Andrei’s career, see E. S. Hurwitz, Prince Andrej

Bogoljubskij: The Man and the Myth, Studia historica et philologica 12, sectio slavica 4

(Florence: Licosa Editrice, 1980); and Limonov, Vladimiro-Suzdal’skaia Rus’,pp.38–98.

48 PSRL, vol. i, cols. 379–82.

49 Novgorodskaia pervaia letopis’,p.223.

50 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 603–5.

112

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Rus’ principalities (1125–1246)

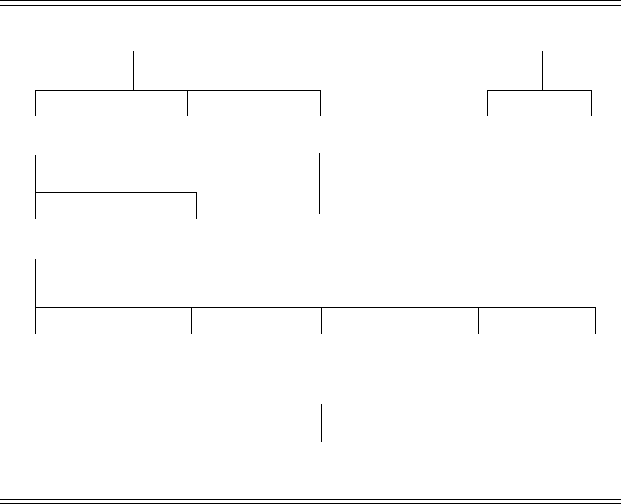

Table 5.6.

The House of Chernigov

Oleg

d. 1115

David

d. 1123

Vsevolod

d. 1146

Igor’

d. 1147

Sviatoslav

d. 1164

Sviatoslav

(Sviatosha)

d. 1143

Iziaslav

d. 1161

Sviatoslav

d. 1194

Iaroslav

d. 1198

Igor’

d. 1201

Vladimir

d. 1200

Oleg

d. 1204

Vsevolod

the Red

d. 1212

Gleb

d. 1215?

Mstislav

d. 1223

Mikhail

d. 1246

commanded by his son Gleb to Riazan’.

51

Vsevolod, however, captured the

princeling. In his anger, Sviatoslav sought to avenge himself against the

House of Monomakh by taking David Rostislavich of Vyshgorod captive

while the latter was hunting. After failing to do so, he abandoned Kiev

and David’s brother Riurik occupied it. Sviatoslav’s campaign to free Gleb

from Vsevolod was also a fiasco. He therefore joined his son Vladimir in

Novgorod and became the town’s prince.

52

(See Table 5.6: The House of

Chernigov.)

In 1181 he marched south against Riurik and was joined by his brother

Iaroslav of Chernigov and his cousin Igor’ Sviatoslavich with numerous

Polovtsy. Riurik prudently vacated Kiev and allowed Sviatoslav to occupy it

uncontested. In the meantime, while Igor’, Khan Konchak, and their troops

51 For Roman Glebovich, see N. de Baumgarten, G

´

en

´

ealogies des branches r

´

egnantes des

Rurikides du XIIIe au XVIe si

`

ecle (Orientalia Christiana) (Rome: Pont. Institutum Oriental-

ium Studiorum, 1934), vol. 35,no.94,tablexiv, 11.

52 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 618–20.

113

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

martin dimnik

were making merry across the Dnieper from Kiev, Riurik’s men routed the

revellers. His rival’s victory forced Sviatoslav to accept Riurik as his co-ruler.

53

Duumvirs had administered Kiev in the past. As we have seen, Iziaslav

Mstislavich and his uncle Viacheslav Vladimirovich had shared authority over

Kiev and all its lands. The partnership between Sviatoslav and Riurik was

different. The former was the senior partner and the commander-in-chief, but

he ruled only Kiev. Riurik controlled the surrounding Kievan domains and

lived in the nearby outpost of Belgorod. His patrimony, however, was Vruchii

north-west of Kiev. His control of the towns surrounding Kiev significantly

curtailed Sviatoslav’s power.

On 1 October 1187, Iaroslav Osmomysl of Galich died.

54

During his reign

he had maintained political relations with the Hungarians (his mother was a

Hungarian princess), Poles, Bulgarians and Greeks. According to the chroni-

cles, he fortified towns and promoted agriculture and crafts. Commerce pros-

pered, especially in the lower Prut and Danube regions. Galicia also supplied

the Kievan lands with much of their salt. Despite his great power, however,

Iaroslav never claimed Kiev because he did not belong to a family of the inner

circle.UnfortunatelyforGalicia,on his deathbed he committed a serious politi-

calblunder,perhaps at the insistenceofboyarswhohad become morepowerful

towards the end of his reign. He designated his younger son Oleg, the offspring

of his concubine, rather than the elder Vladimir, the offspring of his wife Ol’ga

the daughter of Iurii Dolgorukii, his successor.

55

Vladimir challenged Oleg

and initiated a general rivalry for Galich.

56

In 1188, taking advantage of the

strife, Sviatoslav Vsevolodovich sought to consolidate his control over all the

Kievan lands. As he and Riurik rode against B

´

ela III of Hungary who had seized

Galich, Sviatoslav proposed to take the town and give it to Riurik in exchange

for his Kievan domains and his patrimony of Vruchii. Riurik refused the

offer.

57

The following year Vladimir escaped from Hungary, where the king was

holding him captive. After the Galicians reinstated him, he requested Vsevolod

Big Nest in Vladimir-Suzdal’ to support his rule. In return, he promised

to be subservient to his uncle. Vsevolod agreed and demanded that all

the princes, notably Roman Mstislavich of Vladimir-in-Volynia, Riurik and

53 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 621–4.

54 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 656–7.

55 For Iaroslav’s family, see Baumgarten, G

´

en

´

ealogies et mariages,tableiii, 13.

56 For the history of Galicia, see V. T. Pashuto, Ocherki po istorii Galitsko-Volynskoi Rusi

(Moscow: AN SSSR, 1950).

57 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 662–3.

114

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Rus’ principalities (1125–1246)

Sviatoslav pledge not to challenge his nephew’s rule. They acquiesced in def-

erence to his military might.

58

Moreover, when making their promises, it

appears that all the princes in the House of Monomakh pledged to acknowl-

edge Vsevolod as the senior prince of their dynasty. Sviatoslav, although an

Ol’govich, also agreed to obey Vsevolod’s directive not to attack Vladimir. In

doing so, however, he lost face as the prince of Kiev.

59

One of Sviatoslav’s most important duties as commander-in-chief was to

defend Rus’ against the Polovtsy. In the past, princes like Iurii had used the

nomads as their auxiliaries, and they would do so again around the turn of

the thirteenth century. For some two decades after the reign of Rostislav

Mstislavich, however, relations between the princes and the tribesmen were

extremely hostile. The horsemen from the east bank of the Dnieper and those

north of the Black Sea raided Pereiaslavl’ and the River Ros’ region south of

Kiev. The tribes living in the Donets basin pillaged, in the main, the Ol’govichi

domains in the Zadesen’e and Posem’e regions.

60

Sviatoslav, Riurik and their allies ledmanycampaigns againstthe marauders.

In 1184 they scored one of their greatest victories at the River Erel’ south of the

Pereiaslavl’ lands, where they took many khans captive.

61

The following year,

however, Sviatoslav’scousin Igor’ Sviatoslavich of Novgorod Severskii suffered

a catastrophic defeat in the Donets river basin (for chronicle illustrations of the

battle, see Plate 7).

62

It became the subject of the most famous epic poem of

Rus’, ‘The Lay of Igor’’s Campaign’ (Slovo o polku Igoreve).

63

Despite his valiant

efforts, however, Sviatoslav failed to defeat the enemy or to negotiate a lasting

peace.

At the peak of his power, Sviatoslav was the dominant political figure in

Rus’. In addition to enjoying the loyalty of all the princes, he also maintained

diplomatic and commercial relations with the Hungarians, the Poles and the

imperial family in Constantinople.

64

Moreover, he was one of the most avid

builders of his day. In Kiev he erected a new court, the church of St Vasilii,

and restored the damaged St Sophia. In Chernigov, he built a second prince’s

58 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 666–7.

59 Dimnik, The Dynasty of Chernigov 1146–1246,pp.193–5.

60 S. A. Pletneva, Polovtsy (Moscow: Nauka, 1990), p. 146; see also Janet Martin, Medieval

Russia 980–1584 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 129–32.

61 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 630–3.

62 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 637–44; see also Martin Dimnik, ‘Igor’s Defeat at the Kayala: the

Chronicle Evidence’, Mediaeval Studies 63 (2001), 245–82.

63 John Fennell and Dimitri Obolensky (eds.), ‘The Lay of Igor’s Campaign’, in A Historical

Russian Reader: A Selection of Texts from the XIth to the XVth Centuries (Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1969), pp. 63–72.

64 PSRL, vol. ii, col. 680.

115

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

martin dimnik

court and the churches of St Michael and the Annunciation. Vsevolod Big Nest

of Vladimir-Suzdal’, David Rostislavich of Smolensk and Iaroslav Osmomysl

of Galich used the Annunciation as the model for expanding their existing

cathedrals and for building new ones.

65

During his reign, it seems, Chernigov

grew to its maximum area to match if not to surpass Kiev in size.

66

Sviatoslav

died in 1194 during the last week of July and was succeeded, according to their

agreement, by Riurik.

67

Riurik Rostislavich

The following year, Riurik invited David from Smolensk to help him distribute

Kievan towns to their relatives. He demonstrated this deference towards his

elder brother because, even as prince of Kiev, he was subordinate to David, the

senior prince of the Rostislavichi. To his regret, in allocating the towns Riurik

neglected Vsevolod Big Nest, whom the Rostislavichi had acknowledged as

their senior prince. After Vsevolod threatened Riurik, he gave Vsevolod the

towns that he had allotted to his son-in-law Roman Mstislavich of Volyn’.

The latter was furious at the turn of events and formed a pact with Iaroslav

Vsevolodovich of Chernigov.

Riurik, fearing that Iaroslav would depose him, asked Vsevolod to make

Iaroslav pledge not to seize Kiev. What is more, he demanded that the

Ol’govichi renounce the claims of their descendants. Iaroslav, proclaiming

it to be a preposterous demand, refused to renounce the rights of future

Ol’govichi to Kiev. He and Riurik therefore waged war until Vsevolod and

David invaded the Chernigov lands. In 1197, Vsevolod, David and Iaroslav

reached a settlement. The latter promised not to usurp Kiev from Riurik, but

refused to forswear the future claims of his dynasty. While negotiating their

agreement, the three senior princes also affirmed the Novgorodians’ right to

select a prince from whichever dynasty they chose. Moreover, they evidently

granted the princes of Riazan’ permission to create an autonomous eparchy

65 B. A. Rybakov, ‘Drevnosti Chernigova’, in N. N. Voronin (ed.), Materialy i issledovaniia

po arkheologii drevnerusskikh gorodov, vol. i (= Materialy i issledovaniia po arkheologii SSSR,

no. 11, 1949), pp. 90–3.

66 Specialists have estimated that, at its zenith in the late twelfth and early thirteenth

centuries, Chernigov covered an area of some 400 to 450 hectares and was arguably

the largest town in Rus’. Kiev encompassed some 360–80 hectares; see Volodymyr I.

Mezentsev, ‘The Territorial and Demographic Development of Medieval Kiev and Other

Major Cities of Rus’:A Comparative Analysis Based on Recent Archaeological Research’,

RR 48 (1989): 161–9.

67 PSRL, vol. ii, col. 680. Concerning Sviatoslav, see Dimnik, The Dynasty of Chernigov

1146–1246,pp.135–212.

116

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Rus’ principalities (1125–1246)

independent of Chernigov. Riurik was not present at the deliberations and his

demands, in particular that Iaroslav sever his pact with Roman, were largely

ignored. Vsevolod’s objective was to keep the Rostislavichi dependent on him

for military assistance. After Iaroslav Vsevolodovich died in 1198,

68

however,

Riurik formed an alliance with his successor Oleg Sviatoslavich.

The following year Roman seized Galich with Polish help. He therewith

became one of the most powerful princes in the land. In 1202, he demonstrated

his might by inflicting a crushing defeat on the Polovtsy and by evicting his

father-in-law Riurik from Kiev. He gave it to his cousin Ingvar’ Iaroslavich of

Lutsk, whose father had ruled the town.

69

Roman himself was not a rightful

claimant, even though he was of Mstislav’s line, because he belonged to a

younger generation than Riurik and Vsevolod Big Nest. The latter, however,

learning from the fate of his father Iurii and the example of his brother Andrei,

didnotoccupyKiev.The Rostislavichiof Smolensk thereforeremainedthe only

claimants from the House of Monomakh. Nevertheless, Vsevolod, Roman and

their sons would keep a watchful eye on the princes of Kiev and at times try

to manipulate their appointments.

In 1203 Riurik, with Oleg of Chernigov and the Polovtsy, retaliated by attack-

ing Kiev. Although he would capture it later on several more occasions, his

sack of the town is of special significance. The chronicler claims it was the

most horrendous devastation that Kiev had experienced since the Christiani-

sation of Rus’.

70

Thatis,contrary to the viewsof many historians, it was greater

than the havoc inflicted by Andrei Bogoliubskii’s coalition. The following year,

however, Roman gained the upper hand once again by forcing Riurik to enter

a monastery.

71

Then, in 1205, after Roman was killed fighting with the Poles,

Riurik reinstated himself in Kiev.

72

Roman had maintained close ties with the Poles (his mother was a Pole)

and Byzantium. After repudiating his first wife Predslava, Riurik’s daughter,

he married Anna, probably the daughter of Emperor Isaac II Angelus.

73

He

also pursued an aggressive policy towards Galich, where he was the first prince

to depose the sons of Iaroslav Osmomysl. This gave his own sons, Daniil and

Vasil’ko, a claim to Galich because they had the right to sit on the throne of

68 PSRL, vol. ii, cols. 707–8; concerning Iaroslav’s career, see Dimnik, The Dynasty of

Chernigov 1146–1246,pp.214–32.

69 PSRL, vol. i, cols. 417–18.

70 PSRL, vol. i, col. 418.

71 PSRL, vol. xxv,p.101.

72 PSRL, vol. i, cols. 425–6.

73 Fennell, Crisis,p.24.

117

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008