Onkvisit S., Shaw J. International Marketing: Analysis and Strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

market is more than four times larger than the US

market.In the case of Amway Corp., a privately held

US manufacturer of cosmetics, soaps, and vitamins,

Japan represents a larger market than the USA.

Sales and profits

Foreign markets constitute a large share of the total

business of many firms that have wisely cultivated

markets abroad (see Marketing Strategy 1.1). The

case of Coca-Cola clearly emphasizes the impor-

tance of overseas markets. International sales

account for more than 80 percent of the firm’s oper-

ating profits. In terms of operating profit margins,

they are less than 15 percent at home but twice

that amount overseas. For every gallon of soda that

Coca-Cola sells, it earns 37 cents in Japan – a

marked difference from the mere 7 cents per gallon

earned in the USA.The Japanese market contributes

about $350 million in operating income to Coca-

Cola (vs. $324 million in the US market), making

Japan the company’s most profitable market. With

consumption of Coca-Cola’s soft drinks averaging

296 eight-ounce servings per person per year in the

USA, the US market is clearly saturated. Non-US

consumption, on the other hand, averages only

about forty servings and offers great potential for

future growth.

Diversification

Demand for most products is affected by such cycli-

cal factors as recession and such seasonal factors as

climate.The unfortunate consequence of these vari-

ables is sales fluctuations, which can frequently be

substantial enough to cause layoffs of personnel.

One way to diversify a company’s risk is to consider

foreign markets as a solution to variable demand.

Such markets even out fluctuations by providing

outlets for excess production capacity. Cold

weather, for instance, may depress soft drink con-

sumption. Yet not all countries enter the winter

season at the same time, and some countries are

relatively warm all year round. Bird, USA Inc., a

16

NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL MARKETING

Whirlpool Corp. expects demand for big appliances in

the US to remain flat through 2009. Luckily, it pro-

jects demand overseas to grow by 17 percent to 293

million units.To be successful overseas, Whirlpool has

reorganized its global factory network and has made

inroads with local distributors. To cut production

costs for all appliances, it devises basic models that

use about 70 percent of the same parts.The machines

are then modified for local tastes.

One of Whirlpool’s TV commercials in India shows

a mother lapsing into a daydream: her young daugh-

ter, dressed as Snow White, is dancing on a stage in a

beauty contest. While her flowing gown is an immac-

ulate white, the other contestants’ garments are

somewhat gray.The mother awakes to the laughter of

her adoring family, and she glances proudly at her

Whirlpool White Magic washer.This TV spot is based

on four months of research that enables Whirlpool to

learn that Indian home-makers prize hygiene and

purity which are associated with white. Since white

garments often become discolored after frequent

machine washing in local water, Whirlpool has

custom-designed machines that are especially good

with white fabrics.

In India, Whirlpool offers generous incentives to

persuade thousands of retailers to carry its products.

It employs local contractors who are conversant in

India’s eighteen languages.They deliver appliances by

truck, bicycle, and oxcart. The company’s sales have

soared, and Whirlpool is now the country’s leading

brand for fully automatic washers.

Source:

“Smart Globalization,”

Business Week

, August 27,

2001, 132ff.

MARKETING STRATEGY 1.1 WHITE MAGIC

Nebraska manufacturer of go-carts and minicars

for promotional purposes, has found that global

selling has enabled the company to have year-round

production.

A similar situation pertains to the business cycle:

Europe’s business cycle often lags behind that of

the USA. That domestic and foreign sales operate

in differing economic cycles works in the favor of

General Motors and Ford because overseas opera-

tions help smooth out the business cycles of the

North American market.

Inflation and price moderation

The benefits of export are readily self-evident.

Imports can also be highly beneficial to a country

because they constitute reserve capacity for the

local economy. Without imports (or with severely

restricted imports), there is no incentive for domes-

tic firms to moderate their prices. The lack of

imported product alternatives forces consumers to

pay more, resulting in inflation and excessive profits

for local firms. This development usually acts as a

prelude to workers’ demand for higher wages,

further exacerbating the problem of inflation.

Employment

Trade restrictions, such as the high tariffs caused by

the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Bill, which forced the

average tariff rates across the board to climb above

60 percent, contributed significantly to the Great

Depression and have the potential to cause wide-

spread unemployment again. Unrestricted trade, on

the other hand, improves the world’s GDP and

enhances employment generally for all nations.

Unfortunately, there is no question that global-

ization is bound to hurt some workers whose

employers are not cost competitive. Some employ-

ers may also have to move certain jobs overseas so

as to reduce costs.As a consequence, some workers

will inevitably be unemployed. It is extremely diffi-

cult to explain to those who must bear the brunt of

unemployment due to trade that there is a net

benefit for the country.

Standards of living

Trade affords countries and their citizens higher

standards of living than otherwise possible.Without

trade, product shortages force people to pay more

for less. Products taken for granted, such as coffee

and bananas, may become unavailable overnight.

Life in most countries would be much more diffi-

cult were it not for the many strategic metals that

must be imported. Trade also makes it easier for

industries to specialize and gain access to raw mate-

rials, while at the same time fostering competition

and efficiency. A diffusion of innovations across

national boundaries is a useful by-product of inter-

national trade (see Marketing Strategy 1.2). A lack

of such trade would inhibit the flow of innovative

ideas.

The World Bank’s studies have shown that

increased openness to trade is associated with the

reduction of poverty in most developing countries.

Those developing countries which chose growth

through trade grew twice as fast as those nations

which chose more restrictive trade regimes. “Open

trade has offered developing nations widespread

gains in material well being, as well as gains in

literacy, education and life expectancy.”

29

Understanding of marketing process

International marketing should not be considered a

subset or special case of domestic marketing.When

an executive is required to observe marketing in

other cultures, the benefit derived is not so much

the understanding of a foreign culture. Instead, the

real benefit is that the executive actually develops a

better understanding of marketing in one’s own

culture. For example,Coca-Cola Co. has applied the

lessons learned in Japan to the US and European

markets. The study of international marketing can

thus prove to be valuable in providing insights for

the understanding of behavioral patterns often taken

for granted at home. Ultimately, marketing as a

discipline of study is more effectively studied.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40

41

42

43

44

45111

17

NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL MARKETING

CONCLUSION

This chapter has provided an overview of the

process and of the basic issues of international mar-

keting. Similar to domestic marketing, international

marketing is concerned with the process of creating

and executing an effective marketing mix in

order to satisfy the objectives of all parties seeking

an exchange. International marketing is relevant

regardless of whether or not the activities are

for profit. It is also of little consequence whether

countries have the same level of economic develop-

ment or political ideology, since marketing is a

universal activity that has application in a variety

of circumstances.

The benefits of international marketing are con-

siderable. Trade moderates inflation and improves

both employment and the standard of living, while

providing a better understanding of the marketing

process at home and abroad. For many companies,

survival or the ability to diversify depends on the

growth, sales, and profits from abroad. The more

commitment a company makes to overseas markets

in terms of personnel, sales, and resources, the

more likely it is that it will become a multinational

corporation. This is especially true when the man-

agement is geocentric rather than ethnocentric or

polycentric. Since many view MNCs with envy

and suspicion, the role of MNCs in society, their

benefits as well as their abuses will continue to be

debated.

The marketing principles may be fixed, but a

company’s marketing mix in the international

context is not. Certain marketing practices may or

may not be appropriate elsewhere, and the degree

of appropriateness cannot be determined without

careful investigation of the market in question.

18

NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL MARKETING

In Southeast Asia, it is sometimes difficult to distin-

guish ultramodern hospitals from luxury hotels.Health

care and comfort are no longer incompatible concepts.

Bangkok’s Bumrungrad Hospital is Thailand’s top-of-

the-range medical facility that has gone well beyond

providing Western-trained doctors and up-to-date

medical equipment. The hospital also provides guest

chefs, bedside Internet access, carpeted wards, and a

helicopter rooftop landing pad. Patients and visitors

are greeted by a white-gloved doorman, attentive bell-

hops, and a concierge who shows guests to their rooms

(some with wet bars). An escalator connects the first

two floors. If you need something to drink or eat, there

are on-premise McDonald’s and Starbucks outlets.

Private health care spending in Asia has reached

$35 billion. Singapore at one time essentially monop-

olized the high-end market due to its success in

attracting well-to-do patients from all over Asia.

Because of Asia’s lower medical costs and world-class

medical treatment, many people choose to combine

their vacations with a medical check-up.

Now Thailand and Malaysia are competing with

Singapore to become the region’s top health care

center. The newcomers are able to offer comparable

procedures (e.g., heart bypasses, cosmetic surgery) in

comparable comfort at savings of as much as 90

percent. They have also joined forces with airlines

and travel agents to offer medical package tours.

Singapore’s hospital operators are fighting back by

operating satellite facilities in lower cost Indonesia

and Malaysia.

These upscaled medical facilities are not without

controversy since they cater only to wealthy cus-

tomers.The practice thus favors the rich over the poor.

The private hospital industry, on the other hand,

argues that it has relieved a burden on the public

system by taking care of medical tourists who can

afford to pay.

Source:

“Asia’s Middle-Class Sick Find Comfort at Opulent

Hospitals,”

San Francisco Chronicle

, February 23, 2002.

MARKETING STRATEGY 1.2 MEDICAL VACATION

CASE 1.1 SONY: THE SOUND OF ENTERTAINMENT

The name Sony, derived from the Latin word

sonus

for sound and combined with the English word

sonny

, was

adapted for Japanese tongues. It is the most recognized brand in the USA, outranking McDonald’s and Coke.

Sony Corp. has $60 billion in worldwide sales, with 80 percent from overseas and 30 percent alone from the USA

(more than sales in Japan). Sony’s stock is traded on twenty-three exchanges around the world, and foreigners

own 23 percent of the stock.

According to the UNCTAD’s

World Investment Report 2002: Transnational Corporations and Export

Competitiveness

, in terms of value-added sales, Sony is ranked No. 80. In other words, Sony is larger than such

economies as Uruguay, the Dominican Republic, Tunisia, Slovakia, Croatia, Guatemala, and Luxembourg. In addi-

tion, in terms of foreign assets, Sony is No. 22. Out of its total assets of $68,129 million, it has $30,214 million

in foreign assets. It also derives $42,768 million from foreign sales out of its total sales of $63,664 million.

Some years ago, the company made an early move into local (overseas) manufacturing, and 35 percent of the

firm’s manufacturing is done overseas. For instance, Sony makes TV sets in Wales and the USA, thus enabling

the company to earn revenues and pay its bills in the same currency. Sony has recently ceased its production of

video products in Taiwan and has moved the operation to Malaysia and China in order to employ cheaper labor.

But Sony will establish a technology center in Taiwan for product design, engineering, and procurement.

Sony has some 181,800 employees worldwide, 109,080 of whom are non-Japanese. In the USA, 150 out of

its 7100 employees are Japanese. Virtually alone among Japanese companies, Sony has a policy of giving the top

position in its foreign operations to a local national. For example, a European runs Sony’s European operations.

Sony was also the first major Japanese firm to have a foreigner as a director. Sony’s late co-founder, Akio

Morita, even talked about moving the company’s headquarters to the USA but concluded that the effort would

be too complicated.

Sony Corp. of America, located in New York, was Sony’s US umbrella company in charge of the US opera-

tions that included Sony Pictures Entertainment (formerly Columbia Pictures) and Sony Music Entertainment

(formerly CBS Records). Because the president, an American, failed to stop rampant overspending of Sony

Pictures Entertainment, Sony ousted him and took a $2.5 billion write-off. Sony’s CEO Nobuyuki Idei has stripped

the New York headquarters of all operational responsibility for the US market and turned it into a second head-

quarters and strategic planning center for the USA. The overall management of Sony’s US operations will be left

to Tokyo. Many of New York’s functions will be delegated to Sony Pictures and Sony Music, both of which will

report to Tokyo. Idei said: “I want to make [Sony Corp. of America] a more direct extension of Sony headquar-

ters in Japan. We don’t need to manage Sony Pictures and Sony Music from New York.” Incidentally, Idei has

been described by friends as “un-Japanese” because he speaks his mind and demands candor from others.

Sources:

“Sony’s New World,”

Business Week

, May 27, 1996, 100ff.

Business Week/21st Century Capitalism

, 90. “Sony’s Idei

Tightens Reins Again on Freewheeling US Operations,”

Wall Street Journal

, January 24, 1997; “Sony Video Products Shift to

Malaysia, China,”

San José Mercury News

, September 23, 2000;

World Investment Report 2002: Transnational Corporations

and Export Competitiveness

, Division on Investment,Technology and Enterprise Development (DITE), UNCTAD, 2002, 90; and

“The Top Foreign Companies,”

Forbes

, July 23, 2002, 124ff.

Points to consider

Do you consider Sony to be an MNC (multinational corporation)? What are the criteria that you use to make

this determination? You need to provide factual evidence to show how these criteria are or are not met.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40

41

42

43

44

45111

19

NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL MARKETING

QUESTIONS

1 What are the strengths and limitations of the AMA’s definition of marketing as adapted for the purpose of

defining international marketing?

2 Distinguish among: (a) domestic marketing, (b) foreign marketing, (c) comparative marketing, (d) inter-

national marketing, (e) multinational marketing, (f) global marketing, and (g) world marketing.

3 Are domestic marketing and international marketing different only in scope but not in nature?

4 Explain the following criteria used to identify MNCs: (a) size, (b) structure,(c) performance,and (d) behavior.

5 Distinguish among: (a) ethnocentricity, (b) polycentricity, and (c) geocentricity.

6 What are the benefits of international marketing?

DISCUSSION ASSIGNMENTS AND MINICASES

1 Before becoming IBM’s chairman and chief executive officer, Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. was a vice-chairman of

American Express. While at American Express, he stated: “The split between international and domestic is

very artificial – and at times dangerous.” Do you agree with the statement? Offer your rationale.

2 Do you feel that marketing is relevant to and should be used locally as well as internationally by: (a) inter-

national agencies (e.g., the United Nations); (b) national, state, and/or city governments; (c) socialist/com-

munist countries; (d) LDCs; and (e) priests, monks, churches, and/or evangelists?

3 Some of the best-known business schools in the USA want to emphasize discipline-based courses and elim-

inate international courses, based on the rationale that marketing and management principles are applica-

ble everywhere. Is there a need to study international marketing? Discuss the pros and cons of the

discipline-based approach as compared to the international approach.

4 Do MNCs provide social and economic benefits? Should they be outlawed?

5 According to Dan Okimoto, a professor of political science at Stanford University, “universities in the 21st

century will have to be international universities serving a collective good, not simply a national good.”

Traditionally, American universities have served their international customers by simply admitting them to

study in the USA.

Nowadays, no longer content to let foreign students and managers come to them, several American uni-

versities are going to their customers instead.The University of Rochester’s Simon Graduate School, in con-

junction with Erasmus University in Rotterdam, offers an executive MBA program. Tulane University’s

Freeman School of Business has a joint program with National Taiwan University.The University of Michigan

has set up a program in Hong Kong for Cathay Pacific Airways managers. The University of Chicago’s

Graduate School of Business has transplanted its executive MBA program to Barcelona.

Discuss the merits and potential problems of American business schools offering their graduate programs

in a foreign land.

NOTES

1 “Russian Weapons Marketing Gets Glitzier, with Western-Style Sales Pitches, Bargains,”

San José Mercury

News

, March 18, 2001.

2 “Gucci, Armani, and John Paul II?”

Business Week

, May 13, 1996, 61; and “John Connelly’s Holy Hook-

Up,”

Business Week

, October 7, 1996, 64, 66.

20

NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL MARKETING

3 “See the World, Erase Its Border,”

Business Week

, August 28, 2000, 113–14.

4 Digital Microwave Corporation 2000 Annual Report, 20–1.

5 Joseph A. Clougherty, “Globalization and the Autonomy of Domestic Competition Policy: An Empirical Test

on the World Airline Industry,”

Journal of International Business Studies

32 (third quarter, 2001): 459–78.

6 Petra Christmann and Glen Taylor, “Globalization and the Environment: Determinants of Firm Self-

Regulation in China,”

Journal of International Business Studies

32 (third quarter, 2001): 439–58.

7 “Do Polluters Head Overseas?”

Business Week

, June 24, 2002, 26.

8 Lenn Gomes and Kannan Ramaswamy, “An Empirical Examination of the Form of the Relationship between

Multinationality and Performance,”

Journal of International Business Studies

30 (first quarter, 1999):

173–88.

9 Masaaki Kotabe, Srini S. Srinivasan, and Preet S. Aulakh, “Multinationality and Firm Performance: The

Moderating of R&D and Marketing Capabilities,”

Journal of International Business Studies

33 (first quarter,

2002): 79–97.

10 The Global 1000,”

Business Week

, July 15, 2002, 58ff.

11 “The International 500,”

Forbes

, July 22, 2002, 124.

12

World Investment Report 2002: Transnational Corporations and Export Competitiveness

, Division on

Investment, Technology and Enterprise Development (DITE), UNCTAD, 2002.

13 Andrea Bonaccorsi, “On the Relationship between Firm Size and Export Intensity,”

Journal of International

Business Studies

23 (No. 4, 1992): 605–35.

14 Jonathan L. Calof, “The Relationship between Firm Size and Export Behavior Revisited,”

Journal of

International Business Studies

25 (No. 2, 1994): 367–87.

15 Yair Aharoni, “On the Definition of a Multinational Corporation,”

Quarterly Review of Economics and

Business

(October 1971): 28–35.

16 “A Fleet-Footed Team in Asian Finance,”

Business Week/21st Century Capitalism

, 1994, 86.

17 “Can Kraft Be a Big Cheese Abroad?”

Business Week

, June 4, 2001, 63–4.

18 “Caterpillar’s Don Fites: Why He Didn’t Blink,”

Business Week

, August 10, 1992, 56–7.

19 Kenichi Ohmae,

The Borderless World

(London: Collins, 1990).

20 “Kazuo Wada’s Answered Prayers,”

Business Week

, August 26, 1991, 66–7.

21 Chi-fai Chan and Neil Bruce Holbert,“Marketing Home and Away: Perceptions of Managers in Headquarters

and Subsidiaries,”

Journal of World Business

36 (No. 2, 2001): 205–21.

22 Robert W. Boatler, “Manager Worldmindedness and Trade Propensity,”

Journal of Global Marketing

8 (No.

1, 1994): 111–27.

23 Stephen J. Kobrin, “Is There a Relationship between a Geocentric Mind-Set and Multinational Strategy?”

Journal of International Business Studies

25 (No. 3, 1994): 493–511.

24 Aviv Shoham, Gregory M. Rose, and Gerald S. Albaum, “Export Motives, Psychological Distance, and the

EPRG Framework,”

Journal of Global Marketing

8 (No. 3/4, 1995): 9–37.

25 T. R. Rao and G. M. Naidu, “Are the Stages of Internationalization Empirically Supportable?”

Journal of

Global Marketing

6 (No. 1/2, 1992): 147–69.

26 Otto Andersen, “On the Internationalization Process of Firms: A Critical Analysis,”

Journal of International

Business Studies

24 (No. 2, 1993): 209–31.

27 “New Rules in Silicon Valley: Go Global from the Outset,”

San José Mercury News

, May 10, 1998.

28 Will Mitchell, J. Myles Shaver, and Bernard Yeung, “Performance Following Changes of International

Presence in Domestic and Transition Industries,”

Journal of International Business Studies

24 (No. 4, 1993):

647–69.

29 Claudia Wolfe, “Building the Case for Global Trade,”

Export America

(May 2001): 4–5.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40

41

42

43

44

45111

21

NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL MARKETING

22

If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better

buy it of them with some part of our own industry.

Adam Smith

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ Basis for international trade

Production possibility curve

Principle of absolute advantage

Principle of comparative/relative advantage

■ Exchange ratios, trade, and gain

■ Factor endowment theory

■ The competitive advantage of nations

■ A critical evaluation of trade theories

The validity of trade theories

Limitations and suggested refinements

■ Economic cooperation

Levels of economic integration

Economic and marketing implications

■ Conclusion

■ Case 2.1 The United States of America vs. the United States of Europe

Trade theories and economic

development

Chapter 2

BASIS FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Whenever a buyer and a seller come together, each

expects to gain something from the other.The same

expectation applies to nations that trade with each

other. It is virtually impossible for a country to be

completely self-sufficient without incurring undue

costs.Therefore, trade becomes a necessary activity,

though, in some cases, trade does not always work

to the advantage of the nations involved. Virtually

all governments feel political pressure when they

experience trade deficits. Too much emphasis is

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40

41

42

43

44

45111

23

TRADE THEORIES AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

In 1966, Botswana had only three-and-a-half miles of

paved roads, and three high schools in a country of

550,000 people.Water was quite scarce and precious,

leading the nation to name its currency

pula

, meaning

rain. At the time, Botswana’s per capita income was

$80 a year.

Fast forward it to the new millennium. Botswana,

one of Africa’s few enclaves of prosperity, is now a

model for the rest of Africa or even the world. Its per

capita income has rocketed to $6600.While the other

African currencies are weak,the pula is strong – being

backed by one of the world’s highest per capita

reserves ($6.2 billion).

How did Botswana do it? As a land-locked nation

in southern Africa that is two-thirds desert, Botswana

is a trader by necessity, but, as the world’s fastest

growing economy, Botswana is a trader by design.

Instead of being tempted by its vast diamond wealth

that could easily lead to short-term solutions, the

peaceful and democratic Botswana has adhered to

free-market principles.Taxes are kept low.There is no

nationalization of any businesses, and property rights

are respected.

According to the World Bank’s

World Develop-

ment Indicators

(which reports on the world’s eco-

nomic and social health), the fastest growing economy

over the past three decades is not in East Asia but in

Africa. Since 1966, Botswana has outperformed all

the others. Based on the average annual percentage

growth of the GDP per capita, Botswana grew by

9.2 percent. South Korea is the second fastest per-

former, growing at 7.3 percent. China came in third

at 6.7 percent.

Sources:

“World’s Fastest Growing Economy Recorded in

Africa, “

Bangkok Post

, April 18, 1998; and “Lessons from

the Fastest-Growing Nation: Botswana?”

Business Week

,

August 26, 2002, 116ff.

MARKETING ILLUSTRATION BOTSWANA: THE WORLD’S

FASTEST-GROWING ECONOMY

PURPOSE OF CHAPTER

The case of Botswana illustrates the necessity of trading. Botswana must import in order to survive, and

it must export in order to earn funds to meet its import needs. Botswana’s import and export needs are

readily apparent; not so obvious is the need for other countries to do the same. There must be a logical

explanation for well-endowed countries to continue to trade with other nations.

This chapter explains the rationale for international trade and examines the principles of absolute advan-

tage and relative advantage. These principles describe what and how nations can make gains from each

other.The validity of these principles is discussed, as well as concepts that are refinements of these princi-

ples. The chapter also includes a discussion of factor endowment and competitive advantage. Finally, it

concludes with a discussion of regional integration and its impact on international trade.

often placed on the negative effects of trade, even

though it is questionable whether such perceived

disadvantages are real or imaginary. The benefits

of trade, in contrast, are not often stressed, nor

are they well communicated to workers and

consumers.

Why do nations trade? A nation trades because it

expects to gain something from its trading partner.

One may ask whether trade is like a zero-sum game,

in the sense that one must lose so that another will

gain.The answer is no,because,though one does not

mind gaining benefits at someone else’s expense, no

one wants to engage in a transaction that includes a

high risk of loss. For trade to take place, both

nations must anticipate gain from it. In other words,

trade is a positive-sum game. Trade is about “mutual

gain.”

In order to explain how gain is derived from

trade, it is necessary to examine a country’s pro-

duction possibility curve. How absolute and relative

advantages affect trade options is based on the

trading partners’ production possibility curves.

Production possibility curve

Without trade, a nation would have to produce

all commodities by itself in order to satisfy all its

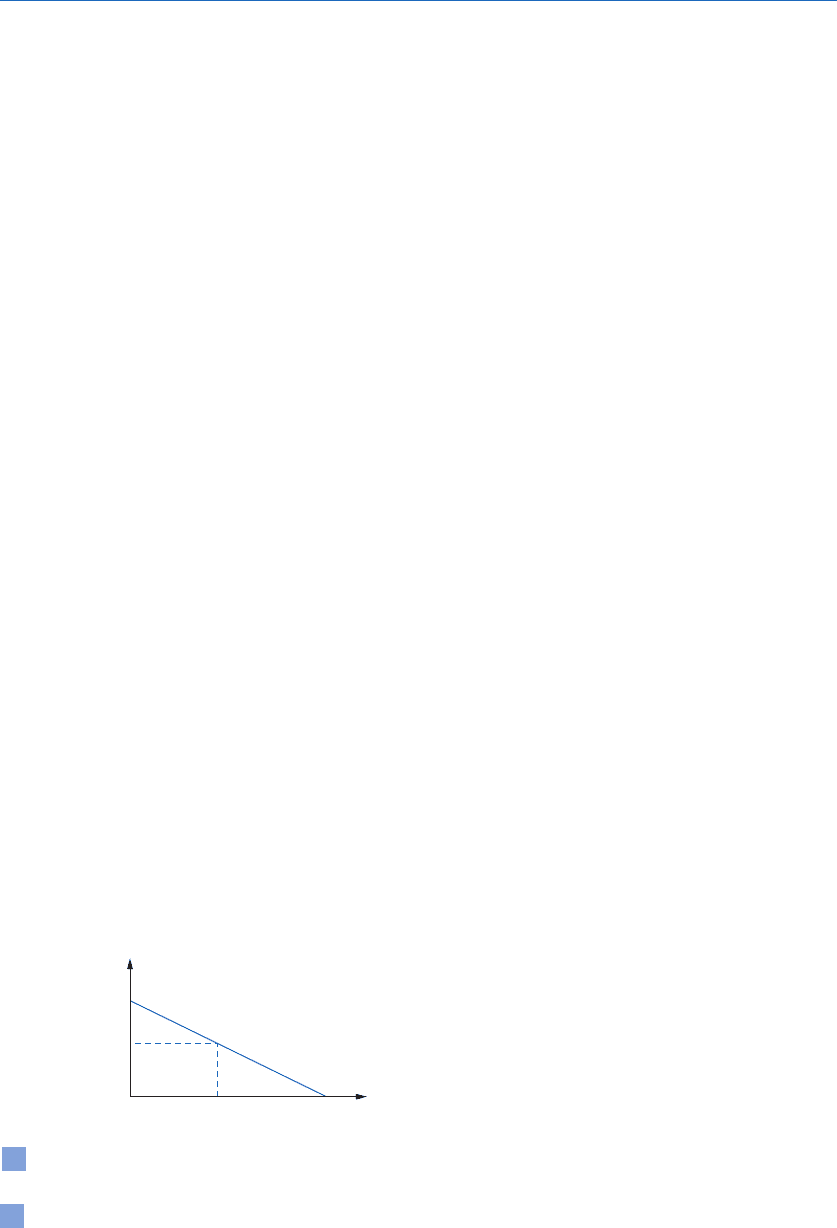

needs. Figure 2.1 shows a hypothetical example of

a country with a decision concerning the produc-

tion of two products: computers and automobiles.

This graph shows the number of units of computer

or automobile the country is able to produce. The

production possibility curve shows the maximum

number of units manufactured when computers and

automobiles are produced in various combinations,

since one product may be substituted for the other

within the limit of available resources.The country

may elect to specialize or put all its resources into

making either computers (point A) or automobiles

(point B).At point C, product specialization has not

been chosen, and thus a specific number of each of

the two products will be produced.

Because each country has a unique set of

resources, each country possesses its own unique

production possibility curve.This curve, when ana-

lyzed, provides an explanation of the logic behind

international trade. Regardless of whether the

opportunity cost is constant or variable, a country

must determine the proper mix of any two prod-

ucts and must decide whether it wants to specialize

in one of the two. Specialization will likely occur

if specialization allows the country to improve

its prosperity by trading with another nation. The

principles of absolute advantage and relative advan-

tage explain how the production possibility curve

enables a country to determine what to export and

what to import.

Principle of absolute advantage

Adam Smith may have been the first scholar to

investigate formally the rationale behind foreign

trade. In his book Wealth of Nations, Smith used the

principle of absolute advantage as the justification

for international trade.

1

According to this principle,

a country should export a commodity that can be

produced at a lower cost than can other nations.

Conversely, it should import a commodity that can

only be produced at a higher cost than can other

nations.

Consider, for example, a situation in which two

nations are each producing two products.Table 2.1

provides hypothetical production figures for the

USA and Japan based on two products: the com-

puter and the automobile. Case 1 shows that, given

certain resources and labor, the USA can produce

twenty computers or ten automobiles or some

combination of both. In contrast, Japan is able to

produce only half as many computers (i.e., Japan

24

TRADE THEORIES AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Units of automobile

Units

of

computer

B

0

A

C

Figure 2.1 Production possibility curve:

constant opportunity cost

produces ten for every twenty computers the USA

produces).This disparity may be the result of better

skills by American workers in making this product.

Therefore, the USA has an absolute advantage in

computers. But the situation is reversed for auto-

mobiles: the USA makes only ten cars for every

twenty units manufactured in Japan. In this instance,

Japan has an absolute advantage.

Based on Table 2.1, it should be apparent why

trade should take place between the two countries.

The USA has an absolute advantage for computers

but an absolute disadvantage for automobiles. For

Japan, the absolute advantage exists for automobiles

and an absolute disadvantage for computers. If each

country specializes in the product for which it has

an absolute advantage, each can use its resources

more effectively while improving consumer welfare

at the same time. Since the USA would use fewer

resources in making computers, it should produce

this product for its own consumption as well as for

export to Japan. Based on this same rationale, the

USA should import automobiles from Japan rather

than manufacture them itself. For Japan, of course,

automobiles would be exported and computers

imported.

An analogy may help demonstrate the value of

the principle of absolute advantage. A doctor is

absolutely better than a mechanic in performing

surgery, whereas the mechanic is absolutely supe-

rior in repairing cars. It would be impractical for

the doctor to practice medicine as well as repair the

car when repairs are needed. Just as impractical

would be the reverse situation, namely for the

mechanic to attempt the practice of surgery. Thus,

for practicality, each person should concentrate on

and specialize in the craft which that person has

mastered. Similarly, it would not be practical for

consumers to attempt to produce all the things

they desire to consume. One should practice what

one does well and leave the manufacture of other

commodities to people who produce them well.

Principle of comparative/relative

advantage

One problem with the principle of absolute advan-

tage is that it fails to explain whether trade will take

place if one nation has absolute advantage for all

products under consideration. Case 2 of Table 2.1

shows this situation. Note that the only difference

between Case 1 and Case 2 is that the USA in Case

2 is capable of making thirty automobiles instead of

the ten in Case 1. In the second instance, the USA

has absolute advantage for both products, resulting

in absolute disadvantage for Japan for both. The

efficiency of the USA enables it to produce more

of both products at lower cost.

At first glance, it may appear that the USA has

nothing to gain from trading with Japan. But nine-

teenth-century British economist David Ricardo,

perhaps the first economist to fully appreciate rela-

tive costs as a basis for trade, argues that absolute

production costs are irrelevant.

2

More meaningful

are relative production costs, which determine what

trade should take place and what items to export

or import. According to Ricardo’s principle of

relative (or comparative) advantage, one country

may be better than another country in producing

many products but should produce only what it pro-

duces best. Essentially, it should concentrate on

either a product with the greatest comparative

advantage or a product with the least comparative

disadvantage. Conversely, it should import either

a product for which it has the greatest compara-

tive disadvantage or one for which it has the least

comparative advantage.

Case 2 shows how the relative advantage varies

from product to product. The extent of relative

advantage may be found by determining the ratio of

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40

41

42

43

44

45111

25

TRADE THEORIES AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Table 2.1 Possible physical output

Product USA Japan

Case 1 Computer 20 10

Automobile 10 20

Case 2 Computer 20 10

Automobile 30 20

Case 3 Computer 20 10

Automobile 40 20