Ogden Daniel. Perseus

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

set of correspondences between the female groups Perseus met in

the course of his quest. The adventure may or may not represent, at

some level, a paradigmatic trial of initiation or maturation. As the

Medusa episode is framed by Perseus’ Greece-based adventures, so

this episode itself frames that of Perseus’ encounter with Andromeda

and the sea-monster, and it is to this that we turn next.

66 KEY THEMES

4

ANDROMEDA AND THE

SEA-MONSTER

THE ORIGINS OF THE ANDROMEDA TALE

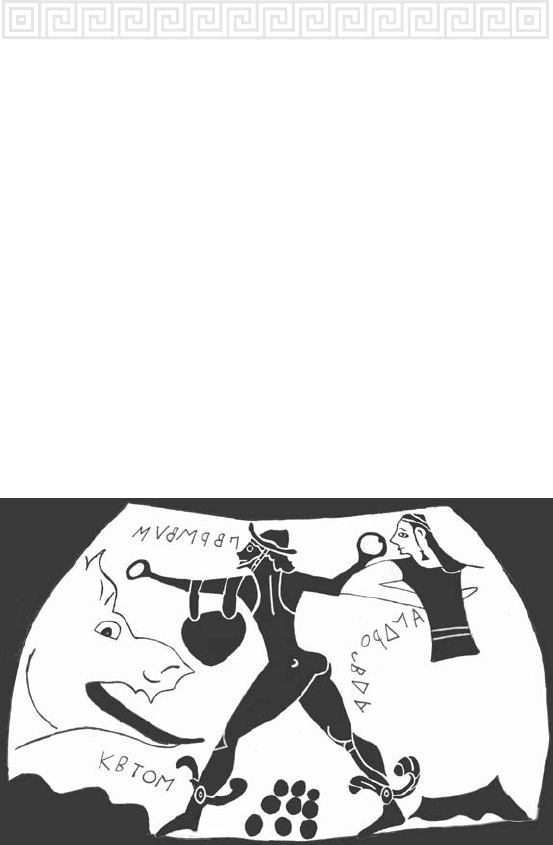

The earliest evidence for the story of Andromeda and the k¯etos or

sea-monster is a Corinthian black-figure amphora of ca. 575–50 bc

(LIMC Andromeda I no. 1 = Fig. 4.1), subsequent by a good century

to the earliest traces of the Medusa episode.

The vase tells a clear story, with the labelled figures of the k¯etos,

Figure 4.1 Perseus pelts the ke¯tos with rocks. Andromeda looks on.

Perseus and Andromeda running left to right. The head of the k¯etos,

all we see of it, may remind modern eyes of a friendly Alsatian.

The rudimentary waves sketched beneath tell us that it attacks

from or with the sea. Perseus, his legs astride, launches round rocks

(pebbles?) at it with both hands, one to the fore and one behind,

from a pile between his feet. He wears his familiar petasos-hat and

winged boots, and the kibisis hangs handbag-like from his out-

stretched arm. The Gorgon-slaying apparel indicates that the k¯etos

episode is already well integrated with the Medusa tradition.

Andromeda stands behind Perseus looking on, her arms awkwardly

akimbo, and perhaps therefore tied.

1

The literary record lags behind. The Hesiodic Catalogue of women

may have been roughly contemporary with the vase, but the surviv-

ing fragments only include reference to the bare fact of Perseus’

marriage to Andromeda (fr. 135 MW). The first recoverable literary

account of the episode is probably Pherecydes’, on the assumption

that his version underlies Apollodorus’ (see chapter 1).

As with the Medusa tale, it has been contended that the Androm-

eda tale derived from the cultures of the Near East. This is hard to

prove, however, not least because of the near universality of dragon-

slaying myths and their damsel-delivering variants. A specific case

has been made that the tale derived quite directly from a Canaanite-

Ugaritic cosmic myth. According to this, the sea-god Yam demanded

the sacrifice to himself of Astarte, the goddess of love, but the

weather-god Baal killed Yam and his sea-monster Lotan, the equiva-

lent of the Biblical Leviathan. But the case is built on a premise that

can not easily be accepted, namely that the Andromeda tale was

originally located in Phoenician Joppa. The Andromeda tale is in

fact associated with Persia and Ethiopia and probably Arcadia, too,

long before its arrival in Joppa, as we will see.

2

One variety of Near-Eastern evidence that does merit attention,

however, is a series of Neo-Assyrian cylinder-seals from Nimrud,

which show the god Marduk attacking the massive sea-serpent

Tiamat. The Corinthian amphora bears a striking resemblance to

this scene. Marduk’s limbs form a similar configuration to Perseus’,

although he is thrusting a sword forward towards the snake with the

hand in front rather than throwing a stone with the hand behind. A

68 KEY THEMES

helper stands behind him, as Andromeda stands behind Perseus.

Between the two of them a constellation is represented by a series of

dots, one of which hovers just above the god’s rear hand, almost as if

it is a stone he is about to throw. It seems that the constellation has

been misinterpreted by the Greek painter or by the tradition within

which he works and so has been translated into Perseus’ stones. In

other representations of the fight between Marduk and Tiamat, we

may note, the god uses a sickle against the serpent-monster. Com-

pelling as the correspondences seem to be, what is borrowed here is

the image-type, not the tale to which it corresponds. However, the

association of a constellation – for all that it is misconstrued on the

Corinthian vase – with a potential model for the representation of

Andromeda’s story is suggestive, when we recall that the catasterisa-

tion of Perseus is tightly associated with the Andromeda episode.

3

THE TRAGIC ANDROMEDA

The Andromeda-tragedies of Sophocles and Euripides seem to have

influenced the subsequent literary and iconographic traditions

profoundly, but unfortunately they survive only in fragments.

The narrative underpinning Sophocles’ play (frs 126–36 Pearson/

TrGF ) seems to have broadly conformed with the Pherecydean-

Apollodoran account, and seems to have ended by looking forward

to the future catasterism of the major players ([Eratosthenes]

Catasterisms 16 and 36). We have no date for the drama, but con-

ventional wisdom holds that it inspired a flurry of Athenian vase

images in the decade 450–440 bc. These show black-African servants

escorting an Andromeda in oriental dress to her place of sacrifice, or

Andromeda already bound between two posts (LIMC Andromeda

I nos. 2–6). A fragment that speaks of ‘the unfortunate woman being

hung out’ (fr. 128a TrGF ) is compatible with such scenes. If the pots

do belong with the play, then they seem to tell us not only its

approximate date, ca. 450 bc, but also that Andromeda was put out

for the monster in the course of the drama, and they seemingly

confirm that the setting was Ethiopia.

4

Euripides’ Andromeda (frs 114–56 TrGF ) was produced in 412 bc

ANDROMEDA AND THE SEA-MONSTER 69

(Scholiast Aristophanes Frogs 53a), and became the subject of

an extended parody by Aristophanes the following year in his

Thesmophoriazusae (1009–1135). This comedy, together with its

ancient commentaries, remains our most important source for

Euripides’ play, but the extraction of the original straight version

from its distorting mirror is no easy task.

5

The play, set again in Ethiopia, evidently opened with Andromeda

chained to a rock (fr. 122 TrGF ) as ‘fodder for the k¯etos’ (fr. 115a

TrGF ). She lamented her lot before a female chorus and as she did

so asked the Echo in the cave behind her to still her voice (fr. 118

TrGF ), a sequence of which Euripides makes great sport. Perseus

arrived on the scene, as he flew back to Argos (not Seriphos, interest-

ingly) with his winged sandals and the head of the Gorgon, and

espied her from above (the theatrical crane will have been deployed

at this point): ‘Ah! What hill do I see with the foam of the sea beating

around it? What image of a maiden do I see made from the working

of natural stones, the statue of a wise hand?’ (fr. 125 TrGF; cf. fr. 124).

Andromeda abandoned herself to Perseus in hope of rescue: ‘Take

me for yourself, stranger, whether you want me to be a servant

or a wife or a slave’ (fr. 129a TrGF ). Perseus had cause to apostro-

phise Eros, presumably after falling in love with Andromeda and so

determining that he must face the k¯etos: ‘Eros, you are the king of

gods and people. You should either stop telling people that beautiful

things are beautiful, or you should work alongside lovers as they

struggle through the toils you ha

ve created for them, so that they

can be successful’ (fr. 136 TrGF; cf. fr. 138). In due course a messen-

ger reported Perseus’ victory over the k¯etos, which had come from

the Atlantic, and described how the exhausted hero had been revived

by local shepherds, who plied him with milk and wine (frs 145–6

TrGF; cf. Plutarch Moralia 22e). Many of these details – Ethiopia,

Eros in attendance, the Atlantic k¯etos and the countrymen offering

milk and wine – are taken up subsequently in the imaginary paint-

ing of Perseus and Andromeda described in the third-century ad

Imagines of Philostratus (1.29), which may perhaps therefore offer

us a synoptic impression of the play’s central action.

Our best clue as to how the play ended is offered by the pseudo-

Eratosthenic Catasterisms:

70 KEY THEMES

Constellation of Andromeda. She is placed in the stars on account of Athena, as

a reminder of Perseus’ labours. Her arms are outstretched, in the position in

which she was set forth for the ke¯tos. In response to this, after being saved by

Perseus, she elected not to remain with her father and mother, but voluntarily

went off to Argos with him, with noble thoughts in mind. Euripides tells the story

clearly in the drama he wrote about her...

([Eratosthenes] Catasterisms 1.17 (cf. 1.15))

The Scholiast to Germanicus’ Aratus, also seemingly drawing ultim-

ately on Euripides, tells that Cepheus and Andromeda were trans-

lated to the stars by Athena, whilst Perseus and the sea-monster

were translated to the stars by Zeus (pp. 77–8, 137–9, 147, 173

Breysig; cf. Hyginus On astronomy 2.11). The future catasterisation

of Perseus and Andromeda and the other principals will have been

foretold at the close at the play, no doubt by a deus ex machina, and

no doubt this was Athena herself.

Vases showing Andromeda tied between two posts in the sup-

posedly Sophoclean fashion continued to be produced after Euripi-

des’ production, but from the beginning of the fourth century bc

they are joined by a series that show Andromeda tied rather to the

rock-arch entrance to a cave, and these are thought to reflect

the Euripidean Andromeda, the cave being the natural home of

Euripides’ Echo. The earliest, a red-figure crater of ca. 400 bc (LIMC

Andromeda I no. 8), is held to illustrate Euripides’ play more closely

than others. On this Andromeda is bound to a rock, surrounded by

the figures of Perseus, Cepheus, Aphrodite, Hermes and a woman

who may represent either the chorus or Cassiepeia.

6

This pair of tragedies evidently did much to maintain interest in

Andromeda in the age of Alexander and the early Hellenistic period.

Nicobule, a rare female writer working at some point prior to Pliny

the Elder, told that in his final dinner Alexander himself performed

an episode from Euripides’ Andromeda from memory (FGH 127 fr. 2).

Some remarkable events recorded by Lucian testify to the continuing

popularity of Euripides’ play in the age of the Successors (How to

Write History 1). During the reign of Lysimachus (306–281 bc) the

tragic actor Archelaus performed his Andromeda for the people of

Abdera in a midsummer heatwave, as a result of which a feverish

ANDROMEDA AND THE SEA-MONSTER 71

disease fell upon them. After a series of distressing physical symp-

toms, they became crazy for tragedy and would shout out the

Andromeda’s monodies, notably ‘Eros, you tyrant over gods and

men’ (fr. 136 TrGF ). The fever and folly dissipated only with the win-

ter freeze. It was about the same time that Eratosthenes compiled the

original version of his Catasterisms or ‘Star myths’ and drew heavily

and explicitly on both Andromeda tragedies to do so, their finales in

particular (frs 15–17, 22 and 36). New tragedies, too, were devoted to

Andromeda in the early Hellenistic age by Lycophron (TrGF 100 T3)

and Phrynichus ‘II’, the son of Melanthas (TrGF 212 T1).

The early Hellenistic period was also the age in which the Latin

poets began to put Greek themes into their own tongue, and they,

too, were evidently caught up in the contemporary passion for

Andromeda tragedies. We know of three Latin Andromedas. In the

third century Livius Andronicus wrote an An

dromeda the unique

fragment of which appears to refer to Poseidon’s flooding (Ribbeck

3

i p. 3 = Warmington: ii pp. 8–9). Ennius’ Andromeda belonged to the

later third or earlier second century bc. The fragments (Ribbeck

3

i

pp. 30–2 = Warmington: i pp. 254–61) tell us that Cassiepeia’s boast

was once again the cause of Andromeda’s distress (fr. 3). The sea-

monster ‘was clothed in rugged rock, its scales rough with barn-

acles’ (fr. 4), perhaps in anticipation of its petrifaction by Perseus.

And the disarticulated limbs of the slain monster were scattered

by the sea, which foamed with its blood (fr. 8). Accius wrote his

Andromeda in the second century ad (or early first). The surviving

fragments (Ribbeck

3

i pp. 172–4 = Warmington ii pp. 346–353)

describe Andromeda as imprisoned in a jagged rock, in a condition

of filth, cold and hunger (fr. 8). No doubt this cave was also the

precinct fenced around with the bones of the sea-monster’s former

victims and rank with the remains of their decaying flesh (fr. 10).

Roman audiences always enjoyed their gore.

7

THE IMPERIAL ANDROMEDA

The most elaborate account of the tale of Perseus’ rescue of

Andromeda to survive is to be found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses

72 KEY THEMES

(4.663–5.235), which reached its final form in 8 ad. This is the

account that has had the most central and profound impact on the

subsequent western tradition. Once again, the boast of Cassiope

(the variant form of the name Cassiepeia favoured in Latin) is the

source of the trouble, but the Nereids and Poseidon are extruded

from the tale. We are only told that Ammon, the great prophetic god

of Egyptian Siwah, has ordained that Andromeda be sacrificed to

the sea-monster. Perseus overflies Ethiopia after petrifying Atlas,

and espies Andromeda pinned out on the rock below. He falls in love

with her at once, and makes an agreement with her ready and will-

ing parents that he may marry her if he delivers her. Perseus dis-

patches the monster by stabbing it repeatedly in its flank. To Ovid

again we owe our only extended narrative of the Phineus episode. As

Perseus and Andromeda are celebrating their wedding feast with

Cepheus, Phineus bursts in with his followers to claim the bride

formerly betrothed to him. A bloody battle breaks out with the fol-

lowers of Cepheus, reminiscent both of Iliadic battle scenes and

more particularly of the battle of the Lapiths and the Centaurs at the

wedding feast later in the same poem (12.210–536). The immediate

impact of the Metamorphoses account can be seen in Manilius’

poetic explanation of the origin of the constellation of Andromeda,

published a few years later (Astronomica 5.538–634), about which

we will have more to say. The popularity of the Andromeda tale in 79

ad Pompeii is amply attested by the many surviving frescoes in the

city showing her story (LIMC Andromeda I nos. 33–41, 67–72, 91–3,

100–1, 103–12). We may presume that the entirety of Roman Italy

was so decorated.

The popularity of Andromeda in Roman murals goes a long way

towards explaining her popularity also in the literature of ekphrasis,

the evocation of imaginary paintings in words, that came to thrive

from the second century ad onwards. In his later second-century ad

novel Le

ucippe and Cleitophon, Achilles Tatius gives us an ekphrasis

of an imaginary diptych painting which balances a panel of Pro-

metheus bound to his rock with one of Andromeda bound to hers

(3.6–7). As often, we find Perseus coupled with Heracles, who res-

cues Prometheus in the corresponding panel. Ekphrasis-literature

likes to confuse boundaries between artistic representation and

ANDROMEDA AND THE SEA-MONSTER 73

supposed real life. Here, we are told, we have a painting of a notion-

ally real woman, who, beautiful and suspended in the cave-mouth,

consequently resembles a statue displayed in an alcove. A spiny

serpentine k¯etos breaks the waves to lurch towards us, as Perseus,

naked save for his Cap of Hades, cloak and winged sandals, descends

from the air to the attack. We find a broadly similar ekphrasis of an

imaginary Andromeda fresco in Lucian’s The Hall (22), probably

written ca. 170 ad. In the early third century the elder Philostratus

offered another ekphrasis of a painting, this time one depicting the

happy scene just after Perseus’ killing of the k¯etos, which reddens

the sea with its blood (Imagines 1.29). This vignette, in which the

local cowherds (not shepherds here) ply the recovering Perseus with

milk and wine, seems to owe much to Euripides, as we have seen. In

Heliodorus’ mid-fourth-century novel Ethiopica we are told of fur-

ther imaginary paintings of Perseus and Andromeda, no doubt in

salute to the tradition of Andromeda ekphraseis that had flourished

over the previous two centuries (4.8, 10.14; cf. 1

0.6). These deco-

rate the walls of the Ethiopian royal palace in which the heroine

Charicleia is born. We learn that in one of them Perseus is shown

releasing a completely naked Andromeda from the rock. The role of

this painting in the novel is a pivotal one, and one that constitutes

an interesting commentary on the Andromeda tradition.

THE CATASTERISMS

It is conceivable that the constellations of Perseus, Andromeda,

Cepheus, Cassiepeia and the k¯etos were developed in conjunction

with the remainder of the Andromeda story as we know it. This is

first attested iconographically, as we have seen, ca. 575–50 bc. It has

been precariously contended that the constellation of Perseus must

have been identified before ca. 550, on the basis that it bisects the

zodiac, which was brought into Greece at this time. Otherwise, all we

can do is note that the catasterisms may have featured in Aeschylus’

Phorcides ([Eratosthenes] Catasterisms 22) at some point in the earl-

ier fifth century, and that they certainly featured in Sophocles’

Andromeda of ca. 450 bc ([Eratosthenes] Catasterisms 16, 36, etc.).

8

74 KEY THEMES

The tradition of making star-pictures in which the characters

underlying the constellations are drawn beneath the relevant group-

ings of stars is usually held to go back to Eudoxus of Cnidus (floruit

ca. 360 bc). Our earliest iconographic record of this tradition is to be

found on the globe of the second-century ad Farnese Atlas in Naples

(LIMC Perseus no. 195). Eudoxus’ star-pictures were taken up avidly

by subsequent astronomical and astrological literature, and were

evidently much reproduced in it: Aratus’ Phaenomena; Eratosthenes’

original Catasterisms, and the ‘pseudo-Eratosthenic’ version of it

that survives; Hipparchus’ commentary on Eudoxus and Aratus;

the translations of Aratus into Latin by Cicero and Germanicus,

with the Latin commentaries on the latter; Manilius’ Astronomica;

Hyginus’ Astronomia. It is to these texts that we owe much of

the information we have about the wider Andromeda myth. The

Catasterisms describes the constellation of Perseus in the following

terms:

9

He has the following stars:

on each shoulder: one bright one [i.e. two in all]

on the tip of his right hand: one

on his elbow: one

on the tip of his left hand, in which he appears to hold the Gorgon’s head: one

on the head of the Gorgon: one

on his torso: one

on his right hip: one bright one

on his right thigh: one bright one

on his knee: one

on his shin: one

on his foot: one dim one

on his left thigh: one

one his knee: one

on his shin: two

around the Gorgon’s locks: three

In total, nineteen. The head and the sickle are seen without stars, but they seem

to be visible to some in the form of a dense cloud.

([Eratosthenes] Catasterisms 22)

ANDROMEDA AND THE SEA-MONSTER 75