Murphy Martin. Small Boats, Weak States, Dirty Money. Piracy & Maritime Terrorism in the Modern World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

127

contemporary piracy: tho who, the why and the where

ese days we work on a contractual basis. All we have to do is wait for an order to

come in, with the coordinates of where the ship is to be attacked. Our forces go in,

take the ship and capture the sailors. en the replacement crew (a group of profes-

sional sailors) comes in to deliver the ship to the customer.

477

e local pirates therefore serve as a labour pool that can be called upon

when needed; once a hijack has been completed, they are left behind. As

another pirate, who called himself Anderson, told the journalist Tom Mc-

Cawley: “We’re just the grunts”.

478

Frécon recounts the example of a pirate

organiser, a Singaporean Chinese named Chen, who brought pirates to an

island in the Anambas archipelago from where they raided shipping for a

number of months.

479

ere is, in other words, a link between piracy at the

lowest level and piracy at the highest; between what can be described as

“common piracy” and “organised piracy”, between attacks on local fisher-

men and local boats and attacks on international traffic. What is not clearly

understood is now these links are maintained and what sparks them into

life. however, as Samuel pyeatt Menefee has put it: “It seems reasonable to

assume that piracies which today affect international trade have arisen in

a milieu in which local piracy is viewed as a successful business”, and that

if littoral states do not tackle incidents of low-level piracy and the links,

real or potential, between local and transnational groups not tracked, then

littoral and user states will be blinded to the rise of maritime transnational

crime as “attacks on fishing boats, if not checked, lead in time to attacks

on supertankers”.

480

477 Latitudes, p. 26. An almost identical account appears in Alex perry, ‘Buccaneer

tales in the pirates’ lair: From island hideaways brigands plague Asia’s shipping

lanes as they have for generations’, TIMEasia. com, 20-27 Aug., 2001.

478 Tom McCawley, ‘Sea of trouble’, FEER, 27 May 2004, p. 52.

479 Frécon, ‘piracy and armed robbery at sea along the Malacca Straits’, p. 77.

480 Menefee, ‘under-Reporting of the problems of Maritime piracy and Terrorism’,

p. 257.

129

3

CONTEMpORARY pIRACY:

IRRITATION OR MENACE?

Pirate typology

In 1993 the IMO attached extracts from a working group report on piracy

in the Malacca Straits to its Maritime Security Committee Circular 622

(MSC/Circ. 622). Following discussions with interested parties, the report

made the judgement that an armed attack on a fishing boat could “hardly

be counted in the same league as an armed attack on a VLCC off Raf-

fles Light”. Deliberately disregarding attacks on vessels below 100 GRT, it

concluded that piracy in the area could be divided into three categories and

that these categories were also applicable elsewhere:

“Low-level armed robbery” (LLAR): an opportunistic attack mounted close to

land.

“Medium-level armed assault and robbery” (MLAAR): piracy carried out further

from shore, often in narrow sea lanes, and therefore a more serious hazard to ship-

ping with a high chance that violence will be used and crew members murdered.

“Major criminal hijack” (MChJ): well resourced and practiced operations in which

violence would commonly be employed to take over and steal not merely the mon-

ey or cargo on board a ship but the ship itself.

1

1 International Maritime Organisation, ‘piracy And Armed Robbery Against

Ships: Recommendations to Governments for combating piracy and armed

robbery against ships’, Maritime Safety Committee Circular 622 (MSC/Circ.

622), 22 June 1993, Annex: Extracts from the Report of the IMO Working

Group on the Malacca Strait Area, paragraphs 4-8. See also Edward Fursdon,

‘Sea piracy–or Maritime Mugging?’ INTERSEC, vol. 5, no. 5, May 1995, p.

166, where he attributes the classifications to the IMB. It has never used them.

p Mukundan, conversation with author May 2006.

130

small boats, weak states, dirty money

peter Chalk suggests a similar, more geographically based categorisa-

tion: harbour/anchorage attacks, attacks against vessels on the high seas or

in territorial waters and hijackings of commercial vessels on the high seas

(including the phantom ship phenomenon).

2

Neither categorisation is entirely satisfactory. Both place the emphasis

too firmly on piracy in the maritime context. ere is no denying that

piracy has its most visible effects at sea and pirate activity can compromise

maritime safety and security. piracy, however, “crosses the beach”. It is as

much a land-based activity as a maritime activity. Its origins are on land, its

bases and its markets are on land, and many of its most pernicious effects

are felt on land. at said, the degree to which it affects events on land de-

pends largely on the degree to which it is an organised activity with links to

other organised crime, or to official or political corruption, that is to say to

the modern day equivalent of peter Earl’s “unscrupulous men”.

3

Anderson proposes a more satisfactory categorisation from a historical

perspective. he sees three types based on what he calls piracy’s form or

expression: parasitic, which feeds on successful maritime trade or wealthy

littorals; episodic, which comes about as the result of the weakening of

large-scale political power and the consequent distortion in trading pat-

terns; and intrinsic, in which piracy is a component part of a society’s fiscal

or commercial life.

4

When applying his own criteria to current circum-

stances he suggests that “piracy committed on commercial shipping, al-

though perhaps organised by criminal groups and essentially parasitic, can

have elements of intrinsic predation” because pirates and their vessels are

able to blend into local shipping and local communities might “knowingly

give them shelter and support”.

5

is is almost certainly the case among

many remote, coastal communities in Southeast Asia. It is also worth re-

membering the claim of some Somali pirate groups that they were levying

“taxes” on ships using their waters, and while this might, in many cases,

have been a clever conceit it is no different from what other societies, also

branded as piratical, have done in the past.

6

2 Chalk, ‘reats to the Maritime Environment’, p. 4. See also Wood, ‘piracy

is Deadlier than Ever’; and Young and Valencia. ‘Conflation of piracy and

terrorism’.

3 Earle, e Pirate Wars, pp. 20-1.

4 Anderson, ‘piracy and World history’, pp. 86 & 93-4.

5 Ibid., p. 98

6 Ibid., p. 83. See also Alfred p. Rubin. e Law of Piracy (2

nd

edn.), Irvington-on-

hudson: Transnational publishers, 1998, pp. 21-2.

131

contemporary piracy: irritation or menace?

however, James Warren’s argument that there are similarities between

Southeast Asian piracy at the end of the eighteenth and twentieth centu-

ries, coinciding on both occasions with booms in trade with China, opens

up the economic perspective: that at least some of the piracy in the region

might be episodic and rise and fall in response to market demand in China

or elsewhere.

7

Given, however, that common pirates prey on local and

not international traffic, and given that they lack the resources to supply

the Chinese market directly, the market stimulus must apply at a higher

and more organised level—one that appreciates that there is a profit to

be made in stealing cargoes in the waters of Southeast Asia states with

weak law enforcement regimes and disposing of them in China with cor-

respondingly weak or corrupt customs and border protection. In the case

of Somalia the pirates are clearly extracting a profit from the almost total

absence of effective law enforcement, either on land or in the country’s

adjacent waters, by kidnapping seafarers from wealthier states, an oppor-

tunity that has been facilitated greatly by modern high-speed communica-

tion and fund transfer mechanisms.

erefore, when thinking about the problem of contemporary piracy in

terms of its potential impact on national or international security, a more

flexible typology might have greater practical application. When evaluating

how much piracy represents a threat to security, as opposed to maritime

safety, in a particular country or region, or internationally, two assessments

must be made. e first is an assessment of the country or region’s vulnera-

bility. e second is an assessment of the threat posed. Generally speaking,

the more organised pirate activity becomes the more the threat increases.

8

Vulnerability must therefore be measured against the degree of pirate or-

ganisation in a given area and the ability of that organisation to gain access

to sometimes distant markets, for a risk assessment to be made. Against this

background, pirate organisation can be assessed on a scale that ranges from

common criminal piracy to highly organised criminal piracy.

Assessments of this kind are undertaken by a number of governmental

and commercial bodies in different parts of the world. Very broadly, the

interests that are affected by piracy and are interested in its control or sup-

7 Warren, ‘A tale of two centuries’, p. 1.

8 Young and Valencia reach a similar conclusion: “piracy encompasses a wide range

of criminal behaviour (that) corresponds to an escalating scale of risk and return

(as) does the apparent degree of organisation of the attackers”. Young and Valen-

cia, p. 272. See also Young. Contemporary Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia, pp.

3, 65

132

small boats, weak states, dirty money

pression are the trading community (ship owners, operators and their cus-

tomers who are interested in supply security), the insurance industry, litto-

ral states, major international trading nations (the “user” states) and, once

they are engaged, naval powers. piracy affects different interests in different

ways. In the real world, each interest that is threatened by piracy makes an

assessment of its seriousness based on its own, largely subjective, criteria.

ese assessments might achieve a degree of objectivity and consistency

by assigning numerical values to them, and by revisiting them regularly,

but they are all, in the end, subjective and open to challenge. Each interest

assesses the threat piracy presents on its own matrix. is might include

the location of the attacks, the types of vessel that are subjected to attack

and what is taken from them, the scale of the losses, the sustained level of

violence, the threat to free navigation and, perhaps most important, the

damage piracy might inflict on the reputation or political standing of the

state or its government. Each interest “weights” these criteria according

to its own priorities, but given that the attitude of states is the key to any

response, it is the last that is likely to have the most influence on policy.

More recently—since the attacks of 9/11 and the attempted sinking of the

uSS Cole and the Limburg—it is the real or suspected link between piracy

and terrorism that has tended to overshadow all others.

Vulnerability assessment

Assessing vulnerability is akin to assessing beauty: much of it lies in the

eye of the beholder. Any assessment needs to take account of the “to

what”, “by whom”, “for whom” and “why” factors and mistakes are easily

made. e physical features of an area, such as the width and depth of a

channel, or weather patterns such as the prevalence of storms or fog, are

generally known and their effects on a region’s susceptibility to piracy,

and the extent to which they together have consequences for its security,

can more or less be calculated. however, most vulnerability assessments

must also take account of less tractable human factors, such as corruption

and morale, which are notoriously hard to judge. Even if a coast guard is

well equipped, for example, is that equipment in working order and are

the crews motivated sufficiently to do their jobs? erefore, as much as

the particular physical circumstances of each area need to be recognised,

so too do the differences in history, culture and political priorities that

can mean different interest groups—say littoral states and user states, or

shipping companies and their insurers—viewing the same conditions very

133

contemporary piracy: irritation or menace?

differently. Assessments, in other words, are bound to differ and shared

conclusions are usually a compromise.

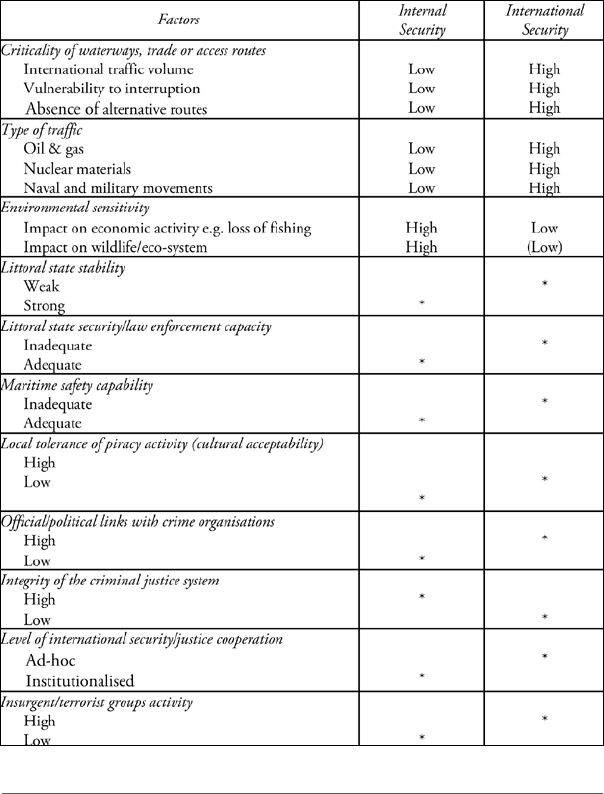

When attempting to assess the vulnerability of specific locations from

an international security perspective, the factors listed in Table One are

likely to be the most significant. For current purposes the factors have been

drawn only indicatively; for practical purposes they would need to be de-

fined more tightly. Where the answers can be located in the left-hand col-

Table 6. Vulnerability Assessment Table: Local conditions that make piracy a potential

problem within and beyond the territorial waters of a littoral state

134

small boats, weak states, dirty money

umn then the issues will generally be ones that affect international interests

slightly, if at all, and can therefore be left to littoral states to deal with. As

the answers tend towards the right-hand column then they will begin to af-

fect the interests first of neighbouring states, then regional states and finally

extra-regional states to the point where the issues can be regarded as be-

ing of international concern. Responses to these issues will in turn escalate

from the neighbourly to the international. e most worrying escalation

occurs if, during its transition from the left-hand column to the right, an

issue moves from being a security concern to being the focus of a real or po-

tential security dispute; that is, it moves from being of little or no political

importance to one with high political implications. Examples of the latter

include the pirate attacks on the Vietnamese boat people, which caused

tensions among Malaysia, Singapore, ailand and Vietnam and between

these countries and the international community; also the pirate attacks off

Somalia in 2006 and once they re-started again in 2007 that have attracted

the attention of the uN.

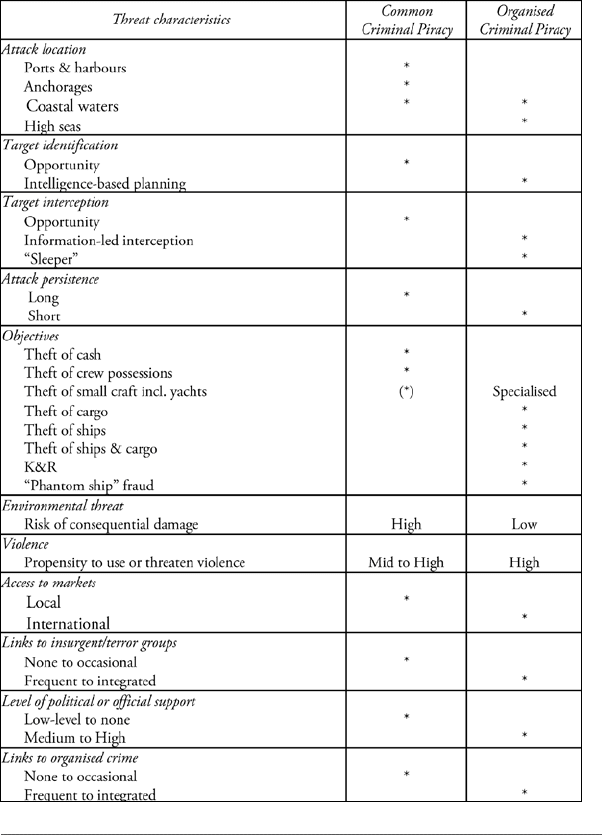

reat assessment

reat is also difficult to measure, though perhaps less so than vulnerabil-

ity. piracy patterns in particular areas, even the capabilities of particular

groups, are often known. What are usually less well understood are the

connections the gangs might have to wider organised crime networks, poli-

ticians, and just possibly insurgent or terrorist organisations, and how these

are likely to influence the gangs’ activities and reach. Nonetheless, a general

principle stands that as the capabilities of a gang increase or criminality in

an area becomes more organised, so the threat to international interests is

likely to become more substantial; on the Table it would begin to move

from the left-hand column to the right. A highly organised gang would

be able to pursue larger and more significant targets, such as oil tankers,

and dispose of their cargoes, or hostages, and obtain hostage payments,

with consequently greater potential financial and social impact, than a less

organised gang. ultimately, these effects could undermine the political

stability of a vulnerable state either directly, via corruption, or indirectly,

via the fiscal strain imposed by the need for larger and better-equipped

security forces. Such instability potentially presents a risk to national and

regional security and has international implications if it affects security in

the vicinity of vital international “hub” ports or in regions with valuable

natural resources such as oil, minerals or even fish. Table Seven indicates

135

contemporary piracy: irritation or menace?

characteristic patterns of “common” piracy and “organised” piracy, that is

to say piracy often undertaken in association with, or under the leadership

of, wider criminal networks, and gives a sense of the contexts within which

each pirate type will tend to operate.

Table 7. reat Assessment Table

136

small boats, weak states, dirty money

Attack location. e location of attack is a useful differentiator between

common and organised piracy. Common criminal piracy is an activity that

takes place close to coasts, in the main when ships are stationary in port or

anchored just offshore waiting to load or unload cargo.

9

Common pirates

use speed and their knowledge of local waters to evade capture and pros-

ecution and some will cross jurisdictional boundaries.

10

Most organised

criminal piracy takes place outside ports in anchorages or, more often, over-

the-horizon in international waters. Organised pirates exploit freedom of

navigation, jurisdictional boundaries and their official status (if they have

it) to escape, to move hijacked vessels—or cargo stolen and then offload-

ed onto another vessel—into another jurisdiction for disposal.

11

When

it comes to the growing phenomenon of maritime kidnap-and-ransom

(K&R), sophisticated organisation is generally apparent. Clues suggesting

this come from reports of victims being moved between multiple locations;

in the case of the crew kidnapped from a Japanese tug, the Idaten, this

involved six moves from boat to boat before they reached land.

12

In other

cases, particular those involving the island of Batam but at other locations

as well, captured crew have been detained on the property of people who

quite obviously possess both wealth and status.

13

Target identification. In the vast majority of cases, common pirates put to

sea on the lookout for small vessels, vessels with low freeboards such as oil

tankers or bulk carriers (although rarely over 20,000 GRT), or those that

9 Out of 445 attacks reported in 2003, 242 took place when ships were either

berthed or at anchor. ICC-IMB piracy Report, 2003, Tables 4 & 5, pp. 8-9;

of the 263 attacks reported in 2007, 145 took place in berths and anchorages.

ICC-IMB piracy Report 2007, Tables 4 & 5, pp. 10-11.

10 See Young and Valencia, ‘Conflation of piracy and terrorism’.

11 McCawley, ‘Sea of trouble’, p. 51. For accounts of the trans-shipment of oil

cargoes at sea see, for example, Gray et al., Maritime Terror, p. 19 on the cases

of the Petro Ranger, Atlanta 15 and Tioman 1. See also ‘Oil piracy proves grow-

ing menace to tanker traffic in South China Sea’, Oil and Gas Journal, 18 Oct.

1999, pp. 23-5, which makes the point that ‘sophisticated networks of black-

market crude oil dealers throughout the region enable them to dispose of oil

products worth millions of dollars relatively quickly’. In addition to the ships

mentioned by Gray et al. it cites the cases of the MT 1 and the President. e

article goes on to point out that the sophisticated level of pirate organisation,

including the use of speedboats, machine guns, radar and jamming equipment,

suggests some military involvement.

12 ‘pirates attack Japanese-owned ship in Malacca Straits’, Kyodo News, 4 April

2005.

13 private information, Aug. 2005.