Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Development involves a combination of knowledge and varied experience. These are

seen as taking place through a combination of both theoretical and practical involve-

ment. The advancement of human relations skills is ideally seen as stemming from

deliberate and constructive self-development.

CHAPTER 23 MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT AND ORGANISATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS

945

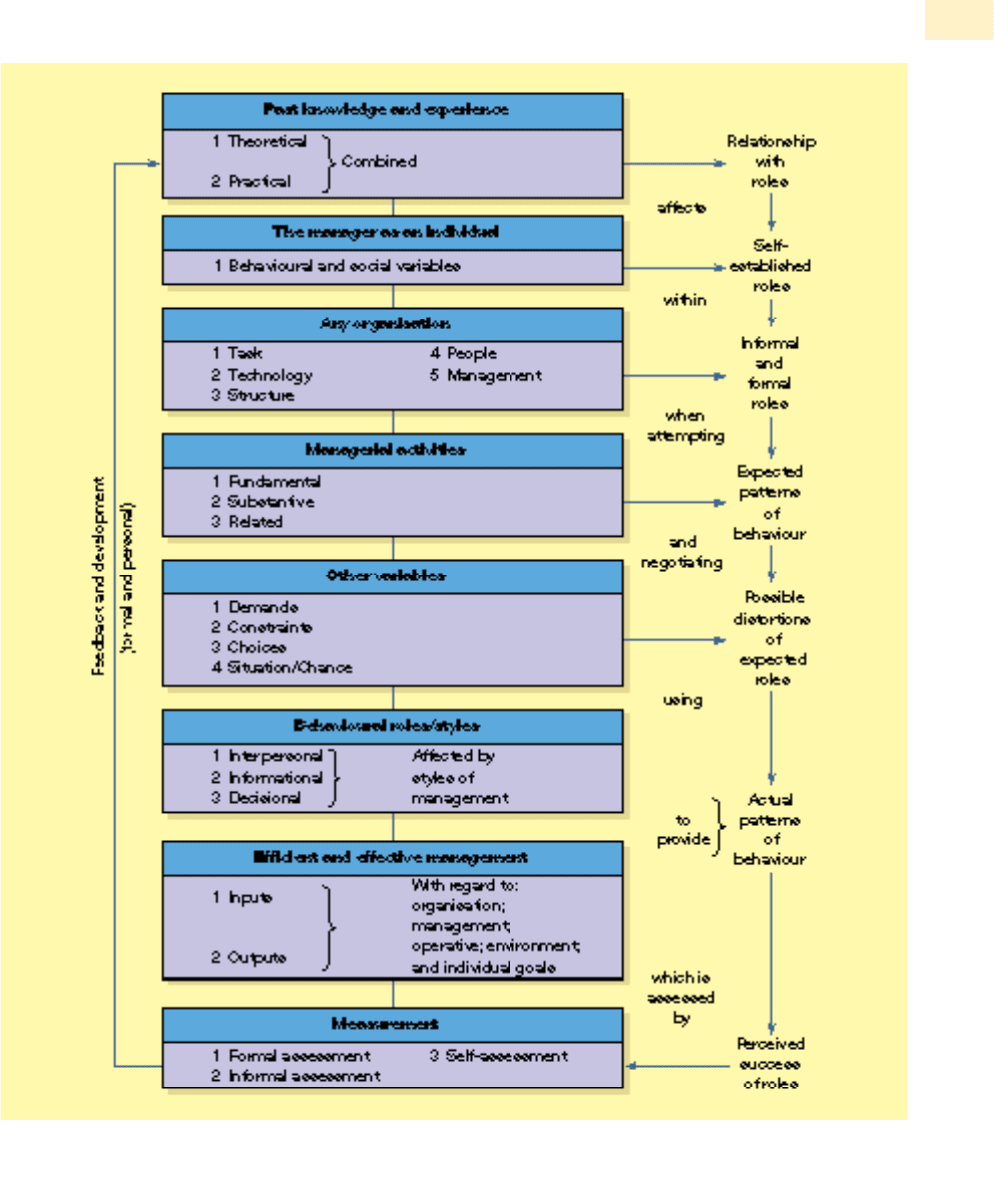

Figure 23.1 An integrated model of managerial behaviour and development

(From Mullins, L. and Aldrich, P. ‘An Integrated Model of Management and Managerial Development’, Journal of Management Development, vol. 7, no. 3. 1998, p. 30.)

Past knowledge

and experience

Behavioural and social variables provide a framework for conceptualising behaviour in

organisations, and include:

■ Links with other individuals and groups within and outside the organisation. These

links may be formal or informal.

■ Personality and people perception.

■ Values.

■ Attitudes.

■ Opinions.

■ Motivation: needs and expectations.

■ Intelligence and abilities: learning and skill acquisition and the assimilation and

retention of past knowledge and experiences.

15

The organisation can be analysed in terms of five main interrelated sub-systems. Two

of these, people and management, can be considered within the context of the ‘behav-

ioural and social variables’ above.

1 Task – includes the goals and objectives of the organisation, the nature of its inputs

and outputs, and work to be carried out during the work process.

2 Technology – describes the manner in which the tasks of the organisation are car-

ried out and the nature of the work performance. The materials, techniques and

equipment used in the transformation or conversion process.

3 Structure – defines the patterns of organisation and formal relationships among

members. The division of work and co-ordination of tasks by which any series of

activities can be carried out.

4 People – the nature of the members undertaking the series of activities as defined by

the behavioural and social variables.

5 Management – is therefore the integrating activity working to achieve the ‘tasks’,

using the ‘technology’ through the combined efforts of ‘people’ and within the formal

‘structure’ of an organisation. This involves corporate strategy, direction of the activi-

ties of the organisation as a whole and interactions with the external environment.

This area of the model attempts to synthesise common views on the basic activities

and processes of management.

1 Fundamental activities

■ Managers can be seen to set and clarify goals and objectives – for instance,

Management by Objectives.

■ A manager plans, examining the past, present and future; describing what needs

to be achieved and subsequently planning a course of action.

■ A manager organises, analysing the activities, decisions and relationships

required, classifying and dividing work, creating an organisation structure and

selecting staff.

■ A manager motivates and develops people, creating a team out of the people

responsible for various jobs while directing and developing them.

■ A manager measures, establishing targets and measurements of performance,

focusing on both the needs of individuals and the control demanded by

the organisation.

2 Substantive activities

■ Communication

■ Co-ordination

■ Integration

■ Having responsibility

■ Making decisions

946

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

The manager as

an individual

Any

organisation

Managerial

activities

These permeate the fundamental activities and are therefore no less important.

Substantive activities are inherent in the process of management and are simply

more descriptive of how the work of a manager is executed.

3 Related activities include, for instance, the personnel function. Personnel policies

help determine the efficient use of human resources and should therefore emanate

from the top of an organisation, be defined clearly and be communicated through

managers at all levels to their staff.

Stewart has developed a model based on studies of managerial jobs which it is sug-

gested provides a framework for thinking about the nature of managerial jobs and

about the manner in which managers undertake them.

16

1 Demands are what anyone in the job has to do. They are not what the manager

ought to do but only what must be done.

2 Constraints are internal and external factors limiting what the manager can do.

3 Choices are the activities that the manager is free to do but does not have to do.

‘Chance’ is one of the factors which determine dominant Managerial Grid style: where,

for instance, a manager has no experience of, or sets of assumptions about, how to

manage a particular situation.

17

According to the contingency approach, the task of the manager is to identify which

style, role or technique will in a particular situation, in particular circumstances,

within a particular organisation and at a particular time contribute best to the attain-

ment of corporate, managerial, social and individual goals.

The activities of managers can be classified into ten interrelated roles.

18

■ Interpersonal roles – relations with other people arising from the manager’s status

and authority. These include figurehead, leader and liaison roles.

■ Informational roles – relate to the sources and communication of information aris-

ing from the manager’s interpersonal roles. These include monitor, disseminator

and spokesperson roles.

■ Decisional roles – involve making strategic, organisational decisions based on

authority and access to information. These include entrepreneurial, disturbance

handler, resource allocator and negotiator roles.

It is emphasised that this set of roles is a rather arbitrary synthesis of a manager’s activ-

ities. These roles are not easy to isolate in practice but they do form an integrated

whole. As such, the removal of any one role affects the effectiveness of the manager’s

overall performance.

This area has strong links with Miner’s ‘role expectations and expected pattern of

behaviours’ theory which is adopted in the model.

19

The variables already described within the model will determine which form of

management is appropriate in any given situation. For example, McGregor’s Theory X

and Theory Y attempt to develop a predictive model for the behaviour of individual

managers.

20

Most managers have a natural inclination towards one basic style of

behaviour, with an emergency or ‘back-up’ style. The dominant style is influenced by

one or several of the following: organisation, values, personal history and chance.

21

Another influential model of management style is centred on ‘exploitive authorita-

tive’, ‘benevolent authoritative’, ‘consultative’ and ‘participative group’ systems. These

systems can then be related to a profile or more specific organisational characteristics.

22

CHAPTER 23 MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT AND ORGANISATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS

947

Other variables

Behavioural

roles and

styles

Managerial efficiency can be distinguished from managerial effectiveness.

23

■ Efficiency is concerned with doing things right and relates to inputs and what a

manager does.

■ Effectiveness is concerned with doing the right things and relates to outputs of the

job and what the manager actually achieves.

Performance is related to the goals of the organisation and the informal and formal

goals of all its individual participants, including managers. The need to take into

account external, environmental variables must not be forgotten.

Managerial effectiveness is a difficult concept either to define or to measure.

Managerial effectiveness cannot be measured simply in terms of achievement, pro-

ductivity or relationships with other people. The manager must be adaptable in adopt-

ing the appropriate style of behaviour which will determine effectiveness in achieving

the output requirements of the job. What is also important is the manner in which the

manager achieves results, and the effects on other people.

Managerial effectiveness may be assessed in three ways:

1 Formal assessment – the pursuit of the systematic development of managers is not

possible without the support of an appraisal scheme providing for periodic assess-

ment on the basis of the best obtainable objectivity. An assessment form is often

used as a valuable aid to objectivity and covers, among other areas: personal skills,

behaviour and attitudes; performance in the allocated role; management knowledge

and competence; and performance related to potential. Assessment should point out

strengths and weaknesses and suggest ways of resolving the latter.

2 Informal assessment – may be given as advice by other managers, or by the behav-

iour and attitudes of staff. The willingness to accept a manager’s authority will

manifest itself through the strength of motivation and therefore measured levels

such as staff turnover, incidence of sickness, absenteeism and poor time-keeping.

3 Self-assessment – the more managers understand about their job and themselves

the more sensitive they will be to the needs of the organisation. Sensitivity should

also extend to the needs of members. This understanding cannot come simply from

studying the results of formal appraisals. Managers must be receptive to the reac-

tions of others and focus consciously on their own actions to try and develop an

understanding of what specifically they do and why.

24

There are two basic kinds of feedback: intrinsic and augmented.

25

■ Intrinsic feedback – includes the usual visual and kinaesthetic cues occurring in

connection with a response – for example, the perception of other people’s visual

reactions towards a management style in a given situation.

■ Augmented feedback – may be concurrent or terminal, and may occur with per-

formance or after it. The frequency, details and timing of each illustrate the

differences between the two – for example, continuous, interim reviews as part of a

system of Management by Objectives, compared with the annual performance

appraisal interview.

Feedback is largely associated with the measurement area of the model but should be

seen as part of the manager’s development package. The specific elements in the pro-

grammes for individual managers are determined by a variety of circumstances

including the outcome of periodic appraisals.

Stewart has commented on the move towards a more individual approach to man-

agement development. There should be a greater emphasis on the individual’s own

setting and needs, and the growing interest in promoting self-development encourages

the individual to adapt general management theories to his or her particular needs.

26

948

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Efficient and

effective

management

Measurement

Feedback and

development

The process of management development should be related to the nature, objectives

and requirements of the organisation as a whole. A prerequisite of management

development is effective human resource planning coupled with procedures for

recruitment and selection. Programmes of management development should be

designed in accordance with the culture and specific requirements of the particular

organisation, and the demands of particular managerial jobs.

27

There should be a clear

management development policy together with regular reviews of individual perform-

ance and a programme of career progression. The execution of management

development activities should be part of a continuous, cumulative process and take

place within the framework of a clear management development policy. Such a policy

should include responsibility for:

■ the implementation, standardisation and monitoring of management development

activities including selection and placement, performance appraisal, potential

appraisal, career planning and remuneration;

■ the availability of finance and resources, and operational support including training,

counselling and problem-solving;

■ the motivation and stimulation to continue with management development activi-

ties at the operational level; and

■ the evaluation and review of policies, procedures and systems.

28

An essential feature of management development is performance review, which was dis-

cussed in Chapter 19. The systematic review of work performance provides an

opportunity to highlight positive contributions from the application of acquired know-

ledge, skills, qualifications and experience. An effective system of performance review

will help identify individual strengths and weaknesses, potential for promotion, and

training and development needs. If performance appraisal is to be effective, there must

be clearly stated objectives which help managers to achieve goals important to them,

and allow them to take control of their own development and progression. Whatever

the nature of a management development programme, one of the most important

requirements of any learning process is the need for effective feedback. Without feed-

back there can be no learning. Feedback should be objective, specific and timely and

give a clear indication of how other people perceive behaviour and performance.

Wherever possible there should be supporting evidence and actual examples.

Extracts from the Abbey Performance Development Programme are given in

Management in Action 23.1 at the end of this chapter.

Training and learning

Management development also requires a combination of on-the-job-training,

through, for example, delegation, project work, coaching and guided self-analysis, trial

periods and simulation; and off-the-job-learning, through, for example, external short

courses, or study for a Diploma in Management Studies or MBA qualification. This

training and learning should be aimed at providing a blend of technical competence,

social and human skills, and conceptual ability.

One of the most basic dilemmas faced by designers of courses and by trainers is the

balance between theory and practice; between what may be considered as theoretically

desirable and what participants perceive as practically possible to implement.

Practising managers may be sceptical of what they regard as a theoretical approach;

and there will always be some who maintain that good managers are born, and that

the only, or best way to learn is by experience. However, it is worth remembering the

contention that ‘there is nothing so practical as a good theory’.

29

It is also important to

achieve an appropriate balance between the assimilation of knowledge information

and the development of skills in order to do something.

CHAPTER 23 MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT AND ORGANISATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS

MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

949

Another approach to management development is the use of activity-based exercises

undertaken as part of ‘away days’. The main objective is often the building of team

spirit and working relationships involving formal team dynamics and assessment,

although this may also be linked with a social purpose, for example to develop interac-

tions with colleagues, improve motivation or to thank and reward staff.

30

950

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Developing managers: applying the theory in practice

Many happy returnees writes Richard Donkin

P

articipants can find life back in the office hard. A new

Cranfield study reveals why.

One of the biggest problems for executives who attend

management development courses is applying the theory

back in the workplace. The assimilation of management

ideas and techniques within the employing organisation,

therefore, is beginning to attract increasing attention from

management schools.

Cranfield School of Management has just completed a

body of research. It followed the progress of about 90 indi-

viduals through four of its general management

programmes and contacted them afterwards to discover

how they applied their new skills and how they were

received by other staff when they returned.

Ms Sally Atkinson, a lecturer in organisational behaviour,

and Mr David Butcher, senior lecturer in management

development, undertook the study. They say the research

is important for modelling future courses and for identifying

competencies necessary to put management theory into

practice. They term the requisite underlying personal skills

‘meta-abilities’. In order to define them, they asked course

attendees to complete questionnaires between six months

and 15 months after they had returned to their companies.

Some found the return to work difficult. Typically, they had

little support from colleagues. One returning manager

referred to the ‘dinosaurs at the top’ who were not pre-

pared to change.

It was common for managers to change roles in the six

months after they completed the programme and this

brought a continuity problem: in some cases, their new

boss was not in a position to have a clear view of their per-

formance and needs.

The relationship between the course attendee and an

existing line manager could be far from supportive – some-

times there was active competition. Often the reaction from

line managers amounted to little more than indifference to

the course input. They saw their role as administrative –

one of going through the mechanics. Some had too little

understanding of the principles behind management devel-

opment and learning.

One of the biggest problems for returning managers

was feedback from colleagues. Every manager on each of

the programmes leaves with a personal action plan to pro-

vide the focus for what he or she needs to achieve at both

a personal and organisational level. Managers said in the

study that they found the personal level of the action plan

easier to accomplish because it was within their control.

Not all ran into brick walls, however. One said he had

received ‘tremendous support and encouragement from

my manager’ and had found an increasing willingness

among his team to challenge and discuss issues.

Additionally, his managing director was open to new ideas

regarding organisational structure and strategy.

One manager felt less isolated because his peers and

immediate supervisor had attended the same or similar

programmes so understood what he was trying to achieve.

The research team concluded that one of the most impor-

tant aspects of management training was bringing out and

developing the underlying abilities necessary to make a

business more responsive to change. The study, still in

draft form, defines six qualities that it considers necessary

for effective management:

■ Managerial knowledge – both acquisition of and trans-

lation into practice.

■ Behavioural skills – principally, assertiveness, communi-

cation skills, the ability to influence and develop others.

■ Cognitive abilities – to recognise and hold complex

perspectives and conflicting concepts in the mind, plus

the ability to shift perspectives, remain open-minded

and consider possibilities.

■ Self-knowledge – the ability to select from a range of

behavioural options in response to a particular need.

■ Emotional resilience – self-control, self-discipline,

the ability to cope with pressure and bounce back

from adversity.

■ Personal drive – the ability to motivate yourself

and others.

The Cranfield team believes management development

courses can focus on areas such as self-insight far more

effectively than anything that is possible in the day-to-day

workplace.

The study asks: ‘How many people feel they can speak

frankly and openly with their manager about their perform-

ance? How many managers find the time to think

effectively about their role in someone else’s development?

Even with the best intentions, there is often not the time or

continuity of relationship to help individuals ... progress.’

EXHIBIT 23.1

FT

A particular and increasingly popular approach to management development courses is

through action learning. This was developed by Revans who argues that managerial

learning is learner driven and a combination of ‘know-how’ and ‘know-that’.

According to Revans, learning (L) is based on ‘programmed knowledge’ (P) and ‘ques-

tioning insight’ (Q), so that:

L = P + Q.

31

Typically, action learning involves a small self-selecting team undertaking a practical,

real-life and organisational-based project. The emphasis is on learning by doing with

advice and support from tutors and other course members. Action learning is, there-

fore, essentially a learner-driven process. It is designed to help develop both the

manager and the organisation, and to find solutions to actual problems. For example,

Inglis and Lewis maintain that action learning aims to increase the number of possible

solutions through the involvement of non-experts and posing basic questions such as:

what are we trying to do? what is stopping us? what can we do about it?

32

According to Crainer, action learning appears to be attracting greater attention but

the potential benefits cannot disguise the challenge it presents.

Action learning demands flexibility and fluidity. For many, reared on a diet of chalk and talk, this is

a daunting prospect. Typically, there is no formal structure with facilitators acting as catalysts

rather than as leaders. While some executives are attracted to this, others are wary that action

learning cannot be measured in the conventional sense. Indeed, it is impossible at the beginning

of a program to forecast exactly what benefits each participant will take away with them. Nor can

the benefits of action learning be easily related to the bottom line of business performance. But, if

it is working effectively, action learning should involve a continuous process of self-evaluation.

33

An integral part of action learning is the use of the case study method and simulations

(discussed in Chapter 1). For example, Hazard sees the use of case teaching as the first

step in an action-learning hierarchy.

Case teaching, like all action learning, is difficult to do well and is initially upsetting to a lot of

students. It’s exhausting and you could say it’s inefficient because many answers can be pre-

sented to the problem. I think all the action learning methods are, however, exactly appropriate

to the complexity and ambiguity that managers face. We are training them to think systematically

and reflectively on different situations … They have to learn how to defend and articulate why

they would use certain methods, approaches or tools, and also how to cede ground gracefully in

the face of a superior selection or a better argued position.

34

Integrated approach to management development

Lound suggests a more integrated approach to developing managers which reflects a

three-step process of:

■

developing targeted competencies as and when required, not as and when convenient;

■ developing support mechanisms where each and every subsequent application of

techniques learned will sustain

‘

best practice’ levels of performance; and

■ creating an environment where people can learn quickly and easily from each other.

CHAPTER 23 MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT AND ORGANISATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS

951

It adds: ‘Managers are often eager to get relevant, honest

feedback about how they work, as it is so difficult to get it

inside their organisations. When managed well, a pro-

gramme creates an environment in which individuals both

learn from and stretch each other, and serve as models for

other approaches.’

The Cranfield team believes it is essential that courses

equip managers with the self-awareness to confront the

obstacles that they may encounter on their return. This

presents a new challenge for management development,

they say: ‘It is far more difficult, yet essential, to accom-

pany and guide individuals in the development of their

meta-abilities than it is to present thinking or teach specific

techniques to a group of managers.’

(Reproduced with permission from the Financial Times Limited, © Financial

Times.)

Action learning

In order to achieve this approach Lound maintains that it is vital that human resource

and information technology functions work together. The ultimate objective is no

longer management development, per se, but rather knowledge management and pro-

viding the right managers with the right information in the right format at the right

time.

35

(Knowledge management was discussed in Chapter 10.)

Succession planning and career progression

Management succession planning aims to ensure that a sufficient supply of appropri-

ately qualified and capable men and women are available to meet the future needs of

the organisation. Such men and women should be available readily to fill vacancies

caused through retirement, death, resignation, promotion or transfer of staff, or

through the establishment of new positions. Despite the influence of de-layering,

changes to the traditional hierarchical structures and less opportunities of jobs for life,

there is still an important need for effective succession planning in order to develop

internal talent and help maintain loyalty and commitment to the organisation.

Allied to management development and succession planning should be a pro-

gramme of planned career progression. This should provide potential managers with:

■ training and experience to equip them to assume a level of responsibility compatible

with their ability; and

■ practical guidance, encouragement and support so that they may realise their poten-

tial, satisfy their career ambition and wish to remain with the organisation.

Career progression should involve individual appraisal and counselling. However, care

should be taken to avoid giving staff too long or over-ambitious career expectations. If

these expectations cannot be fulfilled, staff may become disillusioned and frustrated.

Given the nature of today’s business climate, Altman questions whether there is a

strong case for management succession planning. For example, old-fashioned loyalty is

becoming rarer, suitable candidates may not wish to stay the course, directors and

senior managers have little time to coach potential successors, and the tenure of chief

executives is getting shorter. However, while some organisations seem to prefer to shop

around when top jobs become vacant, other successful organisations such as BP and

Tesco, for example, make a virtue of growing their own managerial talent.

36

Nevertheless now that people are less likely to stay with the same company for long

periods of time there does appear to be some doubt about whether succession planning

is really necessary.

952

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Relevance

today?

Management succession: developing leadership at 3M

In a world of furious change, 3M prefers to develop leadership rather than recruit it,

writes Alison Maitland.

P

lenty of managers regard the person likely to take their

job with barely concealed hostility. Paul Davies, by con-

trast, recently presented his boss with a programme to

enhance the prospects of the three people he believes are

best placed to succeed him either immediately, or in a year

or three years’ time.

This was not Mr Davies’ way of hinting he is fed up with

his job. Rather the UK and Ireland director of human

resources at 3M, the global manufacturing giant, was

engaged in succession planning. With its new approach,

the century-old manufacturer of Scotch tape, Post-it notes,

pharmaceuticals and electronic components hopes to keep

up with today’s furious pace of change.

Mr Davies is one of 150 European managers of

Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing who have this year

had to produce action plans for potential successors.

To complement their efforts, 26 prospective leaders in

3M’s European operations are piloting a ‘succession vital-

EXHIBIT 23.2

FT

Management development should be seen as a continuous process, including the prepara-

tion for and responsibilities of a new job, and the manager’s subsequent career progression.

In the absence of any alternative input, many newly appointed managers move into their new job

believing that they have been given the chance based on their previous achievements, and

assume that the key success factors on which they will be assessed will be the same as in their

last position or previous company.

37

In recent years, greater recognition has been given to the significance of life-long learning

and to

continuing professional development

(CPD). For example, with the Chartered

Management Institute CPD is linked to gaining the status of ‘Chartered Manager’.

CHAPTER 23 MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT AND ORGANISATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS

953

ity’ programme. This emphasises skills such as adaptability

that they will need, and offers them training in aspects of

the business of which they have little experience.

These middle managers would in the past have climbed

the two levels to a senior post in five to 10 years. ‘We want

to get them there within five years,’ says Mr Davies. ‘We’re

also aiming to find 10 people out of the 26 who would be

ready for leadership even faster.’

Sensibly, the initiative does not depend on senior man-

agers’ altruism for its success. The company is next year

introducing a new reward system that will place as much

emphasis on senior managers’ ability to cultivate their suc-

cessors as on hitting annual sales targets. ‘Half of what a

leader earns will be for quantitative results and half for the

legacy they leave. The most capable leaders will be those

who fire on both cylinders,’ says Mr Davies.

The leadership drive grew out of a global review of 3M’s

operations conducted last year by McKinsey, the consult-

ants. The European approach is being shared with other

parts of the Minnesota-based group.

Two forces are driving the changes at 3M, which stum-

bled two years ago as a result of the economic crisis in Asia

and Latin America. The company employs 70,000 people

and makes more than 50,000 products in 60 countries, and

has always prided itself on grooming its own leaders.

3M hires outsiders only as graduates or as sales profes-

sionals. Senior executives typically come in from outside

only through acquisitions. ‘Most headhunters are flabber-

gasted that a corporation like ours doesn’t need executive

search for senior or middle management,’ says Mr Davies,

himself a veteran of 28 years.

In a world where bright graduates are frequently chan-

ging jobs and even chief executives are leaving to join

dotcoms, 3M still values long-term careers. The diversity of

the 150 businesses that make up the group can offer wide-

ranging careers. Staff turnover is low.

But with leaner management structures there is a smaller

pool of potential leaders to choose from than in the past. At

the same time, the skills required to deal with rapidly chan-

ging markets are more demanding than 10 or 20 years ago.

What is more, innovation is crucial to 3M’s success:

more than 30 per cent of sales each year come from prod-

ucts that did not exist four years earlier.

In the past, leaders could emerge naturally, but this is

no longer appropriate, he says.

Catriona MacKay, one of the 26 high-flyers, says: ‘The

job has become more visible and we can’t afford to have

people learning on the job.’

The high-flyers’ scheme, which began last September,

involves a three-hour ‘behavioural’ interview designed to

understand a future leader’s character and identify

strengths and weaknesses.

Candidates receive feedback from their team members

and managers. They also pick a ‘champion’, someone

senior in the group to act as mentor while raising their pro-

file in another part of the business.

Ms MacKay chose Bill Matthews, the American head of

the European industrial markets division, so as to gain

greater understanding of the breadth of 3M’s businesses.

At a two-day workshop in Brussels, the group learned

about the skills, or competencies, they need, including

‘organisational agility’ – the ability to manage across func-

tions and businesses.

The workshop also discussed issues, such as the

reduced mobility of dual-income couples, that future lead-

ers face. Ms MacKay, who has been promoted during the

programme to the UK management operating committee,

does not want to move abroad, because her partner

cannot interrupt his training as a surgeon, and they have

two young children.

‘We’re seeing the company having to be much more

flexible because there are good people who can’t all follow

the same path upwards,’ she says.

‘I’ve probably had the most positive and detailed career

management discussions in the last year that I’ve ever had.

I’m being much better supported by a wide range of people

and it’s personally satisfying that I can have a significant

upward career ... despite my personal circumstances.’

(Reproduced with permission from the Financial Times Limited, © Financial

Times.)

CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT (CPD)

A number of professional bodies have developed a competence-based CPD scheme

for their members. As an example, The Institute of Chartered Secretaries and

Administrators defines Continuing Professional Development as:

The systematic maintenance, improvement and extension of professional, technical and manage-

rial knowledge and skill, and the development of personal qualities necessary for the execution of

professional, technical and managerial duties throughout the Chartered Secretary’s working life.

The Institute has identified the following categories which might contribute to CPD:

■ short courses, workshops and seminars;

■ conferences and exhibitions;

■ post qualification studies;

■ personal study;

■ professional activities and meetings;

■ imparting knowledge;

■ professional development profile.

38

Lifelong learning should be the concern of all employees in the organisation and

(despite the title) it is arguable that the concept of CPD should not be seen as applying

only to professionals or managers as opposed to all employees.

39

Clearly, however, CPD

does have particular significance for management development.

An important part of the process of improving the performance of managers is self-

development. Part of being an effective manager is the responsibility to further one’s

own development. A significant factor affecting the success of self-development is the

extent to which individual managers take advantage of development opportunities

around them. This demands that the manager must be able to identify clearly real

development needs and goals, to take responsibility for actions to reach these goals

and recognise opportunities for learning. Self-development has to be self-initiated. But

if this is to be a realistic aim it requires an organisational climate that will encourage

managers to develop themselves and the active support of top management. Managers

need sufficient authority and flexibility to take advantage of situations which are likely

to extend their knowledge and skills. Superiors should be prepared to delegate new and

challenging projects including problem-solving assignments.

Self-development is now widely accepted as an integral part of management devel-

opment. For example, Farren points out that complexity will continue to increase at

every level of society in the twenty-first century and managers will need the depth and

breadth that comes from mastery of a profession or trade. As the rate of change acceler-

ates, business success will require the eye and ear of a master. Mastery requires time

and practice but builds confidence as well as competence.

People who are great at their profession or trade are always learning, questioning, tinkering, and

taking the practice to a new level. These people don’t have to worry about whether they are

employable. They are desperately needed by organizations and industries to address the ever-

changing needs they are drawn to serve. Theybecome natural managers and coaches for those

around them, both formally and informally.

40

The importance of management education, training and development in this country

was highlighted by two major reports, sponsored by the (then) British Institute of

Management, published in 1987. The Constable and McCormick Report

41

and the Handy

Report

42

both drew attention to the low level of management education and develop-

ment of British managers in absolute terms and also relative to major international

954

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Self-

development

MANAGEMENT EDUCATION, TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT