Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GROUPS AND

TEAMWORK

Part 5

Part 2

THE

ORGANISATIONAL

SETTING

Part 3

THE ROLE OF

THE MANAGER

Part 6

ORGANISATIONAL

STRUCTURES

Part 7

MANAGEMENT

OF HUMAN

RESOURCES

Part 8

IMPROVING

ORGANISATIONAL

PERFORMANCE

Part 1

MANAGEMENT AND

ORGANISATIONAL

BEHAVIOUR

Part 4

THE

INDIVIDUAL

Part 5

GROUPS AND

TEAMWORK

The importance of donuts

There are more myths, more stereotypes, about

groups and committees than about most subjects

in organizations … Groups there must be.

Individuals must be co-ordinated and their skills

and abilities meshed and merged. But let us not

be mesmerized. Let us realize that a proper

understanding of groups will demonstrate how

difficult they are to manage. Let us pay more

attention to their creation and be more realistic

about their outcomes

Charles Handy

Understanding Organizations, Penguin Books (1993)

Groups and teams are a major feature of

organisational life. The work organisation and

its sub-units are made up of groups of people.

Most activities of the organisation require at

least some degree of co-ordination through the

operation of groups and teamwork. An

understanding of the nature of groups is vital if

the manager is to influence the behaviour of

people in the work situation. The manager must

be aware of the impact of groups and teams,

and their effects on organisational

performance.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

explain the meaning and importance of work groups

and teams;

distinguish between groups and teams, and between

formal and informal groups;

explain the main reasons for the formation of groups

and teams;

examine factors which influence group cohesiveness

and performance;

review the characteristics of an effective work group

and assess the impact of technology;

analyse the nature of role relationships and role

conflict;

evaluate the importance of groups and teams for

effective organisational performance.

THE NATURE OF WORK

GROUPS AND TEAMS

13

Photo: E. J. van Koningsveld/Red Arrows

Individuals seldom work in isolation from others. Groups are a characteristic of all

social situations and almost everyone in an organisation will be a member of one or

more groups. Work is a group-based activity and if the organisation is to function effec-

tively it requires good teamwork. The working of groups and the influence they exert

over their membership is an essential feature of human behaviour and of organisa-

tional performance. The manager must use groups in order to achieve a high standard

of work and improve organisational effectiveness.

There are many possible ways of defining what is meant by a group. The essential fea-

ture of a group is that its members regard themselves as belonging to the group.

Although there is no single, accepted definition, most people will readily understand

what constitutes a group. A popular definition defines the group in psychological

terms as:

any number of people who (1) interact with one another; (2) are psychologi-

cally aware of one another; and (3) perceive themselves to be a group.

1

Another useful way of defining a work group is a collection of people who share most,

if not all, of the following characteristics:

■ a definable membership;

■ group consciousness;

■ a sense of shared purpose;

■ interdependence;

■ interaction; and

■ ability to act in a unitary manner.

2

Groups are an essential feature of the work pattern of any organisation. Members of a

group must co-operate in order for work to be carried out, and managers themselves

will work within these groups. People in groups influence each other in many ways

and groups may develop their own hierarchies and leaders. Group pressures can have a

major influence over the behaviour of individual members and their work perform-

ance. The activities of the group are associated with the process of leadership (discussed

in Chapter 8). The style of leadership adopted by the manager has an important influ-

ence on the behaviour of members of the group.

The classical approach to organisation and management tended to ignore the

importance of groups and the social factors at work. The ideas of people such as F. W.

Taylor popularised the concept of the ‘rabble hypothesis’ and the assumption that

people carried out their work, and could be motivated, as solitary individuals un-

affected by others. The human relations approach, however, gave recognition to the

work organisation as a social organisation and to the importance of the group, and

group values and norms, in influencing behaviour at work.

Whereas all teams are, by definition, groups it does not necessarily follow that all

groups are teams. In common usage and literature, including to some extent in this

book, there is however a tendency for the terms ‘groups’ and ‘teams’ to be used inter-

changeably. And it is not easy to distinguish clearly between a group and a team.

3

For

PART 5 GROUPS AND TEAMWORK

THE MEANING AND IMPORTANCE OF GROUPS AND TEAMS

Definitions of

a group

Essential

feature of work

organisations

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN GROUPS AND TEAMS

518

example, Crainer refers to ‘teamworking’ as becoming highly fashionable in recent

years. It is a side effect of increasing concentration on working across functional

divides and fits neatly with the trend towards empowerment. However, despite the

extensive literature about teams and teamworking, the basic dynamics of teamworking

often remain clouded and uncertain.

Teams occur when a number of people have a common goal and recognize that their personal

success is dependent on the success of others. They are all interdependent. In practice, this

means that in most teams people will contribute individual skills many of which will be different.

It also means that the full tensions and counter-balance of human behaviour will need to be

demonstrated in the team.

4

According to Holpp, while many people are still paying homage to teams, teamwork,

empowerment and self-management, others have become disillusioned. Holpp poses

the question: what are teams? ‘It’s a simple enough question, but one that’s seldom

asked. We all think we know intuitively what teams are. Guess again. Here are some

questions to help define team configurations.’

■ Are teams going to be natural work groups, or project-and-task oriented?

■ Will they be self-managed or directed?

■ How many people will be on the teams; who’s in charge?

■ How will the teams fit into the organisation’s structure if it shows only boxes and

not circles or other new organisational forms?

Holpp also poses the question: why do you want teams? If teams are just a convenient

way to group under one manager a lot of people who used to work for several downsized

supervisors, don’t bother. But if teams can truly take ownership of work areas and pro-

vide the kind of up-close knowledge that’s unavailable elsewhere, then full speed ahead.

5

Cane suggests that organisations are sometimes unsure whether they have teams or

simply groups of people working together.

It is certainly true to say that any group of people who do not know they are a team cannot be

one. To become a team, a group of individuals needs to have a strong common purpose and to

work towards that purpose rather than individually. They need also to believe that they will

achieve more by co-operation than working individually.

6

Teamwork a fashionable term

Belbin points out that to the extent that teamwork was becoming a fashionable term, it

began to replace the more usual reference to groups and every activity was now being

described as ‘teamwork’. He questions whether it matters if one is talking about groups

or teams and maintains that the confusion in vocabulary should be addressed if the

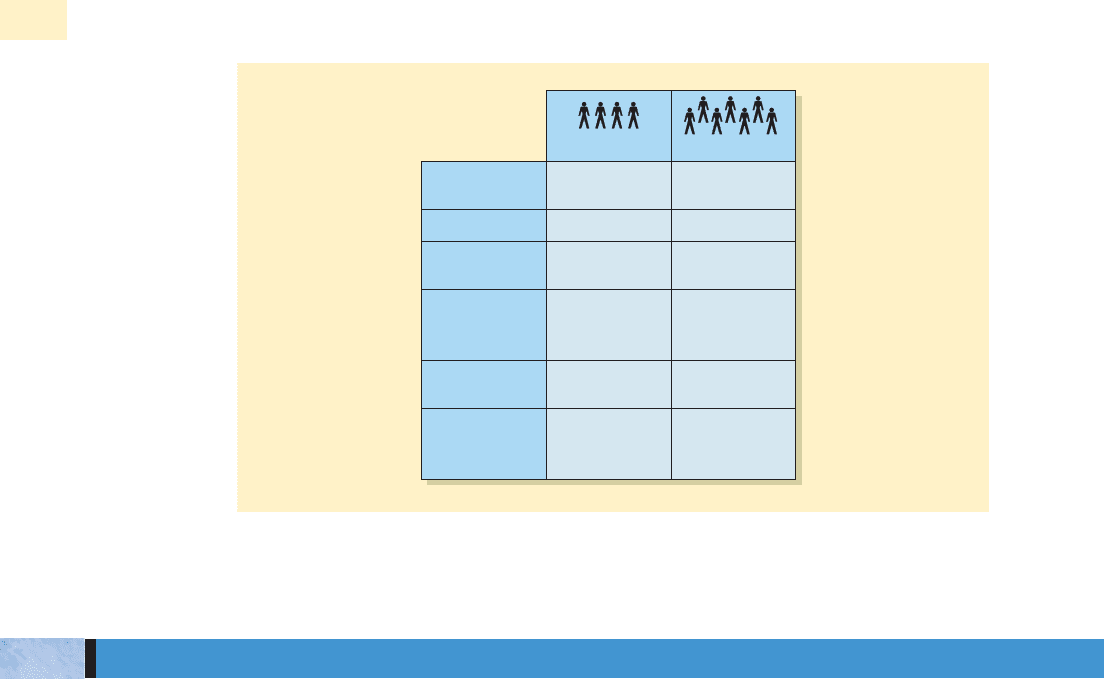

principles of good teamwork are to be retained. Belbin suggests there are several factors

that characterise the difference between groups and teams. (See Figure 13.1.) The best

differentiator is size: groups can comprise any number of people but teams are smaller

with a membership between (ideally) four and six. The quintessential feature of a small

well-balanced team is that leadership is shared or rotates whereas large groups typically

throw up solo leaders.

7

While acknowledging the work of Belbin it appears that the term ‘group’ is often

used in a more general sense and ‘team’ in a more specific context. We continue to

refer to ‘group’ or ‘team’ according to the particular focus of attention and the vocabu-

lary of the quoted authors.

CHAPTER 13 THE NATURE OF WORK GROUPS AND TEAMS

519

The power of group membership over individual behaviour and work performance was

illustrated clearly in the famous Hawthorne experiments at the Western Electric

Company in America,

8

already referred to in Chapter 3. A significant feature was the

attention drawn to the importance and influence of group values and norms. One

experiment involved the observation of a group of 14 men working in the bank wiring

room. It may be remembered that the men formed their own sub-groups or cliques,

with natural leaders emerging with the consent of the members. Despite a financial

incentive scheme where workers could receive more money the more work they did,

the group decided on 6000 units a day as a fair level of output. This was well below the

level they were capable of producing. Group pressures on individual workers were

stronger than financial incentives offered by management.

Informal social relations

The group developed its own pattern of informal social relations and codes and prac-

tices (‘norms’) of what constituted proper group behaviour.

■ Not to be a ‘rate buster’ – not to produce at too high a rate of output compared

with other members or to exceed the production restriction of the group.

■ Not to be a ‘chiseller’ – not to shirk production or to produce at too low a rate of

output compared with other members of the group.

■ Not to be a ‘squealer’ – not to say anything to the supervisor or management

which might be harmful to other members of the group.

■ Not to be ‘officious’ – people with authority over members of the group, for ex-

ample inspectors, should not take advantage of their seniority or maintain a social

distance from the group.

520

PART 5 GROUPS AND TEAMWORK

Dynamic

interaction

Togetherness

persecution of

opponents

Spirit

Role spread

co-ordination

Convergence

conformism

Style

Mutual

knowledge

understanding

Focus on

leader

Perception

Shared or

rotating

SoloLeadership

Crucial ImmaterialSelection

Limited Medium or

Large

Size

Team Group

Figure 13.1 Differences between a team and a group

(Reproduced with permission from R. Meredith Belbin, Beyond the Team, Butterworth-Heinemann, Division of Reed Educational and

Professional Publishing Ltd, © 2000.)

GROUP VALUES AND NORMS

The group had their own system of sanctions including sarcasm, damaging completed

work, hiding tools, playing tricks on the inspectors, and ostracising those members

who did not conform with the group norms. Threats of physical violence were also

made, and the group developed a system of punishing offenders by ‘binging’ which

involved striking someone a fairly hard blow on the upper part of the arm. This process

of binging also became a recognised method of controlling conflict within the group.

According to Riches, one way to improve team performance is to establish agreed

norms or rules for how the team is to operate and rigorously stick to them. Norms

could address the obligations of individual members to the team, how it will assess its

performance, how it will work together, what motivation systems will be used, how it

will relate to customers, and the mechanisms to facilitate an honest exchange about

the team norms and behaviour.

9

A recent study from the Economic & Social Research Council draws attention to the

importance of social norms among employees and questions whether employees are

guided not only by monetary incentives but also by peer pressure towards social effi-

ciency for the workers as a group. ‘Intuitively, social norms among workers must be

important if they work in teams where bonuses are dependent on group, rather than

individual effort.’

10

(You may see some similarity here with the Bank Wiring Room

experiment, discussed above.)

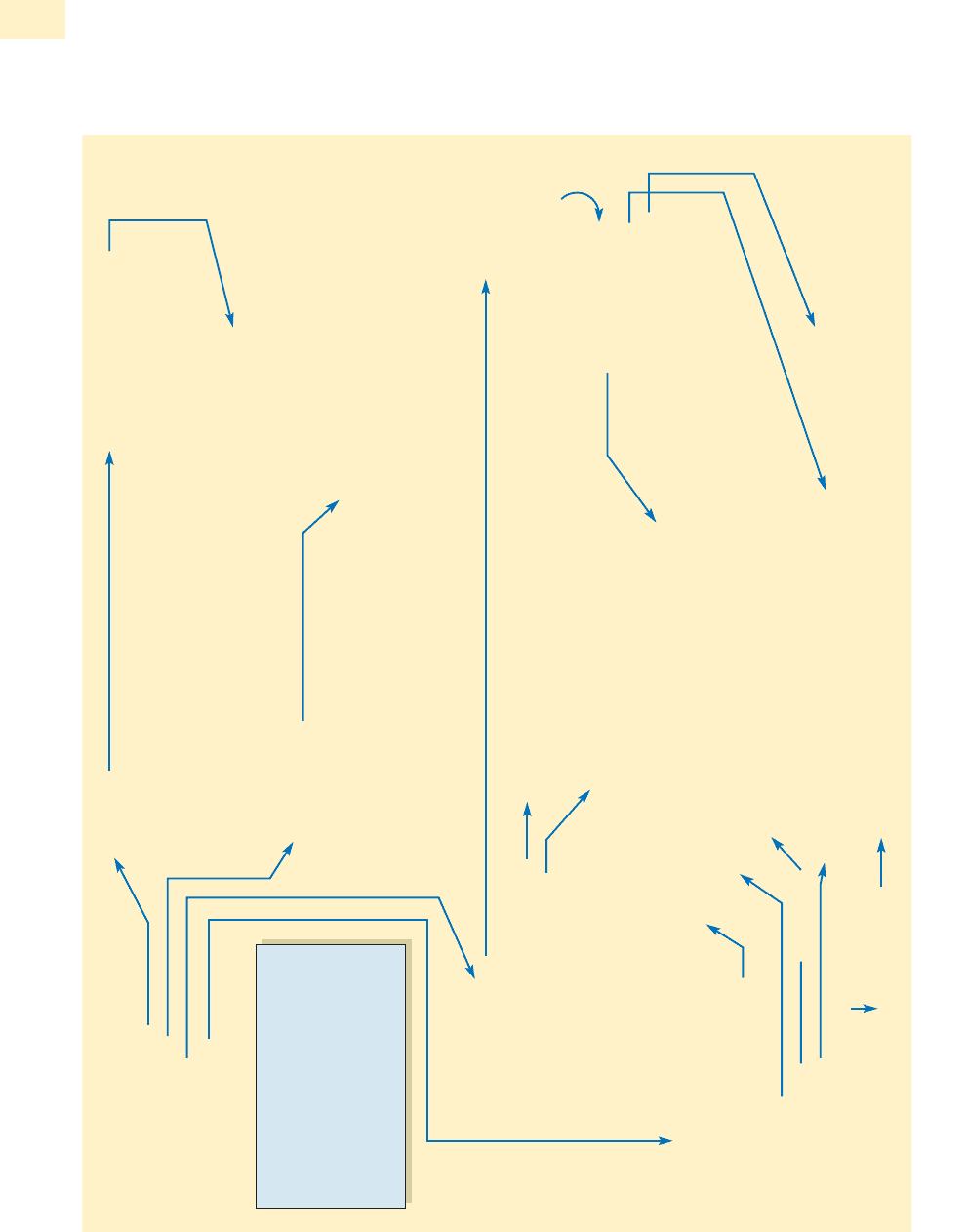

A ‘summary outline’ of group norms is presented in Figure 13.2 on p. 522.

How people behave and perform as members of a group is as important as their behav-

iour or performance as individuals. Not only must members of a group work well as a

team but each group must also work well with other groups. Harmonious working rela-

tionships and good teamwork help make for a high level of staff morale and work

performance. Effective teamwork is an essential element of modern management prac-

tices such as empowerment, quality circles and total quality management, and how

groups manage change. Teamwork is important in any organisation but may be espe-

cially significant in service industries, such as hospitality organisations where there is a

direct effect on customer satisfaction.

11

According to ACAS (the Arbitration, Conciliation and Advisory Service), teams have

been around for as long as anyone can remember and there can be few organisations

that have not used the term in one sense or another. In a general sense, people talk of

teamwork when they want to emphasise the virtues of co-operation and the need to

make use of the various strengths of employees. Using the term more specifically,

teamworking involves a reorganisation of the way work is carried out. Teamwork can

increase competitiveness by:

■ improving productivity;

■ improving quality and encouraging innovation;

■ taking advantage of the opportunities provided by technological advances;

■ improving employee motivation and commitment.

12

An account of teamwork in a small (40-person) company is given in Management

in Action 13.1.

The general movement towards flatter structures of organisation, wider spans of

control and reducing layers of middle management, together with increasing empow-

erment of employees, all involve greater emphasis on the importance of effective

teamworking. ‘There’s no doubt that effective teamwork is crucial to an organisation’s

efforts to perform better, faster and more profitably than their competitors.’

13

CHAPTER 13 THE NATURE OF WORK GROUPS AND TEAMS

521

THE IMPORTANCE OF TEAMWORK

522

PART 5 GROUPS AND TEAMWORK

THE VALUE OF NORMS

•

Counteracts anonymity

•

Supports small-group identity

•

Are legitimate to group members

•

May not support organisation’s formal goals

•

Provides order

•

Provides standards Often implicit

•

Influences behaviour

•

Embodies the informal ‘shadow’ organisation

CHANGING NORMS

A group is often reluctant to change its

norms, so for change to take place ...

• Get group consensus to change

•

Generate support for change

•

Address as many factors as

possible which will help the change.

GROUP NORMS

•

DEFINITIONS OF NORMS

•

EVOLUTION OF NORMS

•

CHANGING NORMS

•

THE VALUE OF NORMS

UNFREEZING

Develop an awareness of

•

the nature of the change needed

•

the methods planned to achieve the change

•

the needs of those affected

• the ways that progress will be

planned and monitored.

TYPICAL NORM STATEMENTS

•

Around here we always ...

•

It doesn’t do to ...

•

We never ...

•

When that happens we ...

IDENTIFYING NORMS

By observation, interview or question you discover

•

behaviour which gets reinforced or rewarded

•

behaviour which gets discouraged or penalised

EVOLUTION OF NORMS

They may evolve through ...

• modelling behaviour on another ‘prestigious’ group

•

accidental discovery of advantageous behaviour

•

witnessing repeated acts

•

unintended consequences of formal decisions.

DEFINITION

A group norm is an assumption or expectation

held by group members concerning what kind

of behaviour is

• right or wrong

•

good or bad

•

allowed or not allowed

•

appropriate or not appropriate.

PROCESS FOR

IMPLEMENTING

NORM CHANGES

(LEWIN’S CHANGE

MODEL)

STAGE 1 UNFREEZING

STAGE 2 CHANGING

STAGE 3 REFREEZING

CHANGING

•

Defining problems

•

Identifying solutions

•

Implementing solution

REFREEZING

•

Stabilising the situation

•

Building and rebuilding relationships

•

Consolidating the systems

Group norms may evolve over a long

period of time. This can lead to them

becoming

•

rigid

•

anachronistic

•

irrelevent for current situations.

Management’s wishes on their own are sometimes not

sufficiently strong to have enough influence to change norms.

Individual changes are rarely, if ever,

effective in changing the norms

of a group.

Norms are an observable aspect of any

group, in or out of the work setting.

New group members are alert to

signals of acceptance or rejection as

they seek to clarify expectations.

They find them in formal and informal

contacts.

Not necessarily pro- or anti-management

Predictability desirable, avoids chaos

Enables the group to evaluate and

control group behaviour

Language, dress, openness/secrecy,

competitiveness, productivity

Expresses unwritten sometimes unspoken rules May encourage ‘we–they’ attitudes

Figure 13.2 Summary outline of group norms

(Reproduced with permission of Training Learning Consultancy Ltd, Bristol.)

Skills of effective teamworking

From a recent study of Europe’s top companies, Heller refers to the need for new man-

agers and new methods, and includes as a key strategy for a new breed of managers in a

dramatically changed environment: ‘making team-working work – the new, indispen-

sable skill’.

14

The nature and importance of teamwork is discussed further in Chapter 14.

According to Guirdham, the growth of teamwork has led to the increased interest in

interface skills at work.

More and more tasks of contemporary organisations, particularly those in high technology and

service businesses, require teamwork. Taskforces, project teams and committees are key ele-

ments in the modern workplace. Teamwork depends not just on technical competence of the

individuals composing the team, but on their ability to ‘gel’. To work well together, the team

members must have more than just team spirit. They also need collaborative skills – they must

be able to support one another and to handle conflict in such a way that it becomes constructive

rather than destructive.

17

A similar point is made by Ashmos and Nathan: ‘The use of teams has expanded dra-

matically in response to competitive challenges. In fact, one of the most common skills

required by new work practices is the ability to work as a team.’

18

Included in a study of top European companies and ‘making teamwork work’, Heller

refers to the happy teams at Heineken. Part of the cultural strength of Heineken is a

realisation that: ‘the best culture for an organisation is a team culture’; and that ‘any

large organization is a team of teams – and people who have to work together as a

team must also think together as a team’.

19

Heller also lists Heineken’s manifesto for

‘professional team-thinking’ (see Figure 13.3) and maintains that ‘Arguing with any of

these eleven points is absurd’.

CHAPTER 13 THE NATURE OF WORK GROUPS AND TEAMS

523

All of us know in our hearts that the ideal individual for a given job cannot be found … but if

no individual can combine all the necessary qualities of a good manager, a team of individ-

uals certainly can – and often does. Moreover, the whole team is unlikely to step under a

bussimultaneously. This is why it is not the individual but the team that is the instrument of

sustained and enduring success in management.

Antony Jay

15

A successful climbing team involves using management skills essential to any organisation

... The basic planning is the foundation on which the eventual outcome will be decided.

Even if it is the concept of a single person, very quickly more and more people must become

involved, and this is where teamwork and leadership begin.

Sir Chris Bonington

16

Happy teams

at Heineken

524

PART 5 GROUPS AND TEAMWORK

Figure 13.3 Manifesto for professional team-thinking at Heineken

(Reproduced with permission from Robert Heller, In Search of European Excellence, HarperCollins Business © 1997, p. 231.)

1 The aim is to reach the best decision, not just a hasty conclusion or an easy consensus. The team

leader always has the ultimate responsibility for the quality of the decision taken – and therefore, for

the quality of the team-thinking effort that has led up to the decision.

2To produce the best professional team-thinking, the team leader must ensure that ego-trips, petty

office politics and not-invented-here rigidity are explicitly avoided. There should be competition

between ideas – not between individual members of the team.

3 The team-thinking effort must first ensure that the best question to be answered is clearly and

completely formulated.

4 The team-thinking process is iterative – not linear. Therefore, the question may have to be altered

later and the process repeated.

5 The team leader is responsible for seeing that sufficient alternatives and their predicted

consequences have been developed for evaluation by the team.

6 The team leader will thus ask ‘what are our alternatives?’ – and not just ‘what is the answer?’

7 The team leader also recognizes that it is wiser to seek and listen to the ideas of the team before

expressing his or her own ideas and preferences.

8 In any professional team-thinking effort, more ideas will have to be created than used. But any idea

that is rejected will be rejected with courtesy and with a clear explanation as to why it is being

rejected. To behave in this way is not naive, it is just decent and smart.

9A risk/reward equation and a probability of success calculation will be made explicitly before any

important decision is taken.

10 Once a decision is made professionally, the team must implement it professionally.

11 When you think, think. When you act, act.

Teamwork’s own goal

There are limitations to the application of teamwork methods in the workplace writes

Victoria Griffith.

T

eamwork has become a buzzword of 1990s’ man-

agement theory. By grouping employees into problem-

solving taskforces, say the theorists, companies will

empower workers, create cross-departmental fertilisation,

and level ineffective hierarchies.

Yet executives know that, in reality, teams and taskforces

do not always produce the desired results. Part of the

problem may lie with the way teams are organised.

Members may fail to work well together for several rea-

sons, from lack of a sense of humour to clashing goals.

Academics in the US have been studying team dynamics

to try to identify problems.

Too much emphasis on harmony

Teams probably work best when there is room for disagree-

ment. Michael Beer, a professor at Harvard Business

School, says: ‘Team leaders often discourage discord

because they fear it will split the team.’ He studied teams

at Becton Dickinson, the medical equipment group, in the

1980s, and found that efforts to paper over differences

sometimes led to bland recommendations by taskforces.

One working group at the company, for example, said

the division’s overall strategic objective was ‘fortifying our

quality, product cost, and market share strengths, while

also transforming the industry through expanded customer

knowledge and product/service innovation’. The group,

says Beer, offered no organisation guidance as to which

factor was more important and why.

Too much discord

Excessive tension can also destroy team effectiveness. A

study published in the Harvard Business Review in June

1997 found that corporate team members disagreed less

and were more productive when everyone had access to

EXHIBIT 13.1

FT