Mises, Ludwig von. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

xxii

Human

Action

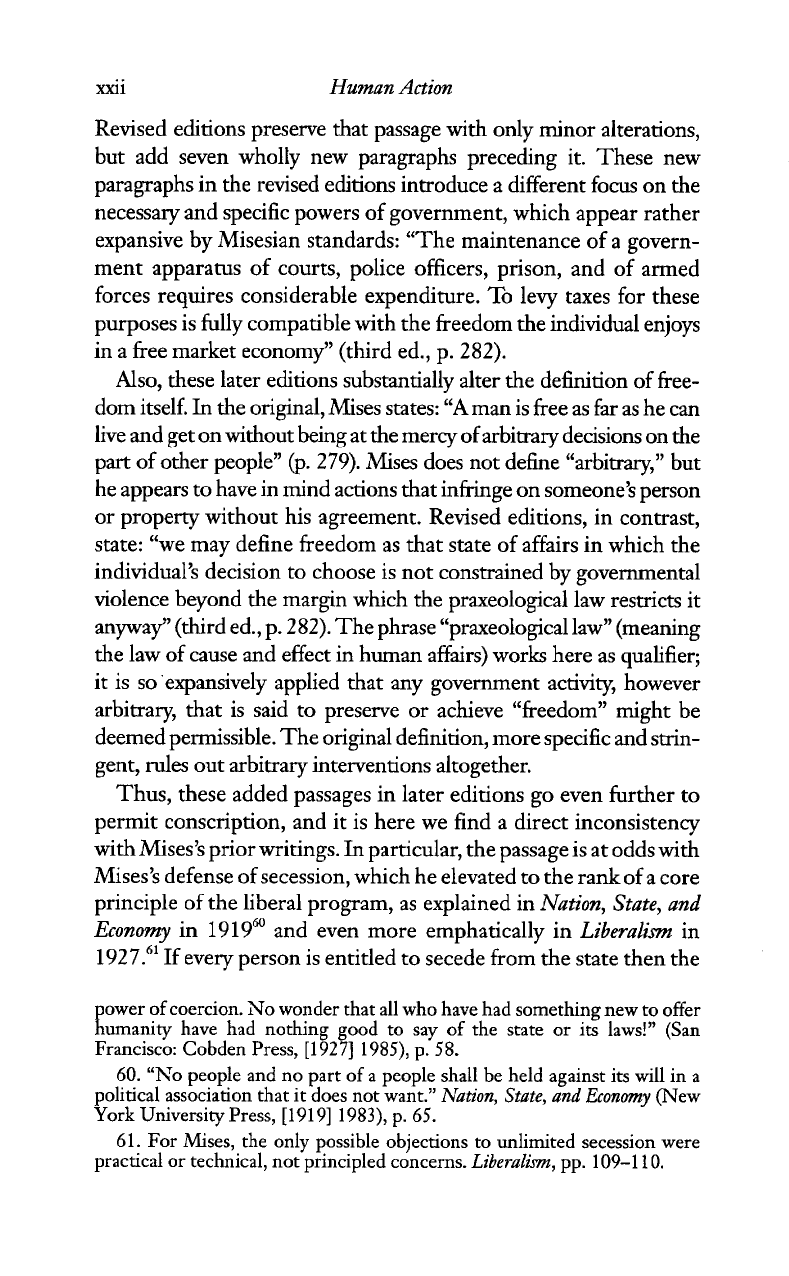

Revised editions preserve that passage with only minor alterations,

but add seven wholly new paragraphs preceding it. These new

paragraphs in the revised editions introduce a different focus on the

necessary and specific powers of government, which appear rather

expansive by Misesian standards: "The maintenance of

a

govern-

ment apparatus of courts, police officers, prison, and of armed

forces requires considerable expenditure. To levy taxes for these

purposes is fully compatible with the freedom the individual enjoys

in a free market economy" (third ed.,

p.

282).

Also, these later editions substantially alter the definition of free-

dom itself.

In

the original, Mises states:

"A

man is free as far as he can

live and get on without being at the mercy of arbitrary decisions on the

part of other people" (p. 279). Mises does not define "arbitrary," but

he appears to have in mind actions that infringe on someone's person

or property without his agreement. Revised editions, in contrast,

state: "we may define freedom as that state of affairs in which the

individual's decision to choose is not constrained by governmental

violence beyond the margin which the praxeological law restricts it

anyway" (third ed., p. 282). The phrase "praxeological law" (meaning

the law of cause and effect in human affairs) works here as qualifier;

it is so 'expansively applied that

any

government activity, however

arbitrary, that is said to preserve or achieve "freedom" might be

deemed permissible. The original definition, more specific and smn-

gent,

rules

out arbitrary interventions altogether.

Thus, these added passages in later editions go even further to

permit conscription, and it is here we find a direct inconsistency

withMises's prior writings.

In

particular, the passage is at odds with

Mises's defense of secession, which he elevated to the rank of a core

principle of the liberal program, as explained in Nation, State,

and

Economy in 191960 and even more emphatically in Liberalism in

1927." If every person is entitled to secede from the state then the

ower of coercion. No wonder that all who have had something new to offer

Eumanity have had nothing good to say of the state or its laws!" (San

Francisco: Cobden Press, [I9271 1985),

p.

58.

60. "No people and no part of

a

people shall be held against its will in a

political association that it does not want." Nation, State, and Economy (New

York University Press, [I91

91

1 983),

p.

65.

61. For Mises, the only possible objections to unlimited secession were

practical or technical, not principled concerns. Liberalism, pp. 109-1 10.

Introduction to the Scholar's Edition

xxiii

state becomes a kind of voluntary organization from which exit is

always allowed; accordingly, any form of conscription would have

to be considered illegitimate and impermissible. Even more strik-

ingly, however, the passage stands in contradiction to the discus-

sion, and rejection, in

Nationalokonomie

of conscription as a species

of interventionism which, according to its own internal "logic,"

leads inevitably to socialism and total war. "Military conscriptjon,"

1Mises wrote, "leads to compulsory public service of everyone capable

of work. The supreme commander controls the entire people,

...

the

mobilization has become total; people and state have become part

of the army; war socialism has replaced the market economy."62

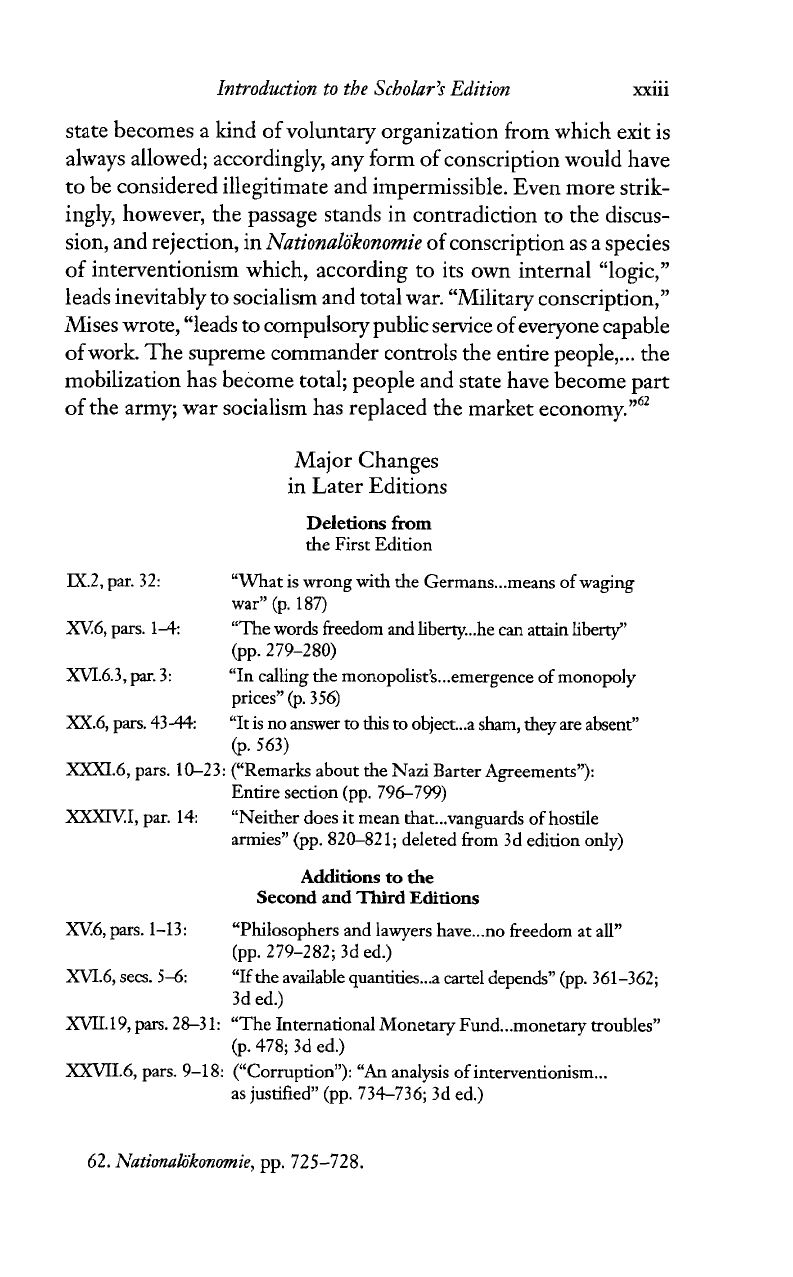

Major Changes

in

Later Editions

Deletions

from

the First Edition

M.2, par. 32:

XV6, pars.

1-4

XVI.6.3,

par.

3:

XX.6,

pars. 43-44:

"What is wrong with the Germans

...

means of waging

war"

(p.

187)

"The words freedom and libe

rty...

he

can

attain

liberty"

(pp. 279-280)

"In calling the monopolist

's...

emergence of monopoly

prices"

@.

356)

"It is no

answer

to this to object

...

a sham,

they

are absent"

@.

563)

XXXI.6,

pars. 10-23: ("Remarks about the Nazi Barter Agreements"):

Entire section (pp. 796-799)

XXXIV.1,

par.

14:

"Neither does it mean that

...

vanguards of hostile

armies7'

(pp.

820-821; deleted from 3d edition only)

Additions to

the

Second

and

Third

Editions

XV.6,

pars. 1-13: UPhilosophers and lawyers have

...

no freedom at all"

(pp. 279-282; 3d ed.)

,XVI.6, sea.

5-6:

"If the available quantities

...

a cartel depends" (pp. 361-362;

3d ed.)

XW.19,

pars. 28-3 1: "The International Monetary Fund

...

monetary troubles"

(p. 478; 3d ed.)

XXVII.6,

pars. 9-18: ("Corruption"):

"An

analysis of interventionism

...

as justified" (pp. 734-736; 3d ed.)

62.

h'atimaliikonomie,

pp.

725-728.

xxiv

Human

Action

H

UW~NACTION,

building on and expanding its German prede-

cessor, transformed Austrian economics, as it is understood

today, into a predominantly American phenomenon with

a

dis-

tinctly Misesian imprint, and made possible the continuation of

the Austrian School after the mid-twentieth century. Thus the first

edition assumes an importance that extends beyond the mere histori-

cal.

It

reveals the issues and concerns that Mises considered primary

when releasing, at the height of his intellectual powers, the most

complete and integrated statement of his career.

In

particular, making

the unchanged first edition available again retrieves important pas-

sages that were later eiiminated, and clarifies questions raised by

unnecessary, and, in some cases, unfortunate additions and revisions

made to later editions.

That the original edition represents the fullest synthesis of

Mises's thought on method, theory, and policy, and is the book that

sustained the Austrian tradition and the integrity of economic

science after the socialist, Keynesian, Walrasian, Marshallian, and

positivist conquests of economic thought, is reason enough to reissue

the original on its fiftleth anniversary, making it widely available for

the first time in nearly four decades. A high place must be reserved

in the history of economic thought, indeed, in the history of ideas,

for ~Wses's masterwork. Even today,

Human

Action

points the way

to a brighter future for the science of economics and the practice

of human liberty

Jeffrey

M.

Herbener (Grove City College)

I-Ians-Hermann Hoppe F~versity of Nevada, Las Vegas)

Joseph

T

Saierno (Pace University

October

1998

23

63.

Jorg G~lido Hiilsmann and David Gordon also contributed to this

Introduction.

FOREWORD

F

K0M the fall of

I

934

until the summer of

1940

I had the

privilege of occupying the chair of International Eco-

nomic Kelations at the Graduate Institute of International

Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. In the serene atmosphere

of this seat of learning, which two eminent scholars, Paul

Mantoux and William

E.

Kappard, had organized and con-

tinued to direct,

I

set about executing an old plan of mine,

to write a comprehensive treatise on economics. The book-

Nationalokonomie, Theorie

des

Handelns

zmd

Wirtschaftens

-was published in Geneva in the gIoomy days of May, 19.10.

The present volume is not a translation of this earlier book.

Although the general structure has been little changed, all

parts have been rewritten.

To my friend Henry Hazlitt

I

wish to off er my very special

thanks for his kindness in reading the manuscript and giving

me most valuable suggestions about it.

I

must also gratefully

acknou~ledge my obligations to Mr. Arthur Coddard for lin-

guistic and stylistic advice.

I

am furthcrmore deeply indebted

to

Mr.

Eugene

A.

Davidson, Editor of the Yale University

Press, and to

Mr.

Leonard

E.

Read, President of the Founda-

tion for Economic Education, for their kind encouragcment

alld

~~nnnrt

rrw*-

I need hardly add that none of these gentlemen is either di-

rectly or indirectly responsible for any opinions contained in

this work.

LUDWIG

vos

MISES

New

York, February,

1949.

Permission has been granted by the publishers to use quatations

from the following works: George Santayana,

Persons and Places

(Charles Scribner's Sons); William James,

The Varieties of

Rkli-

gious Experience

(Longmans, Green

&

Co.); Harley Lutz,

Guide-

posts to

a

Free Ecorzonzy

(McGraw-Hill Book Company); Com-

mittee on Postwar Tax Policy,

A

Tax Program

for a Solvent

America

(The Ronald Press Company).

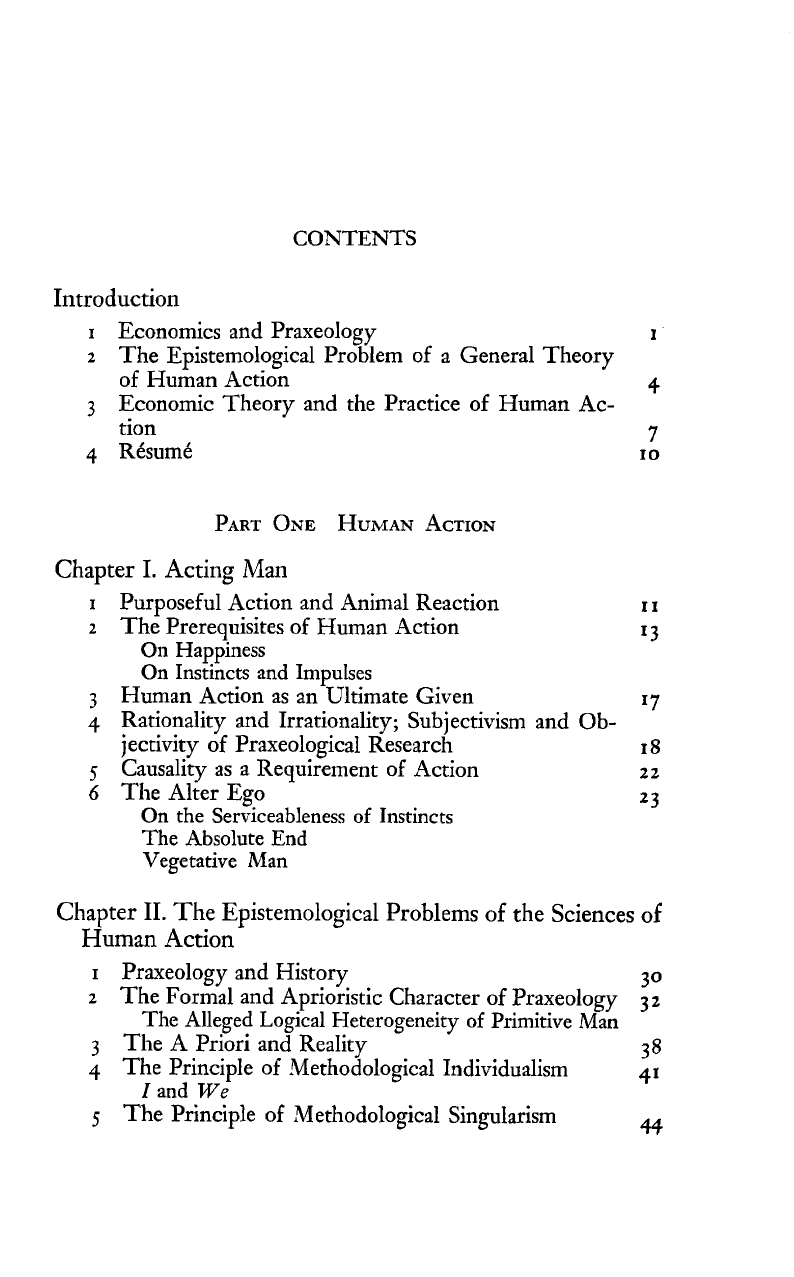

CONTENTS

Introduction

I

Economics and Praxeology

I

2

The Epistemological Problem of a General Theory

of Human Action

4

3

Economic Theory and the Practice of Human Ac-

tion

7

4

RCsumC

10

Chapter

I.

Acting Man

I

Purposeful Action and Animal Reaction

I I

r

The Prerequisites of Human Action

'3

On Happiness

On Instincts and Impulses

3

Human Action as an Ultimate Given

'7

4

Rationality and Irrationality; Subjectivism and Ob-

jectivity of Praxeological Research

I

8

5

Causality as a Requirement of Action

2

z

6

The Alter Ego

23

On the Serviceableness

of

Instincts

The Absolute End

Vegetative Man

Chapter

11.

The Epistemological

Problems

of the Sciences of

Human Action

I

Praxeology and History

30

2

The Formal and Aprioristic Character of Praxeology

32

The Alleged Logical Heterogeneity of Primitive Man

3

The A Priori and Reality

7

8

4

The Principle of hiethodological Individualism

-

4'

I

and

We

5

The Principle of Methodological Singularism

44

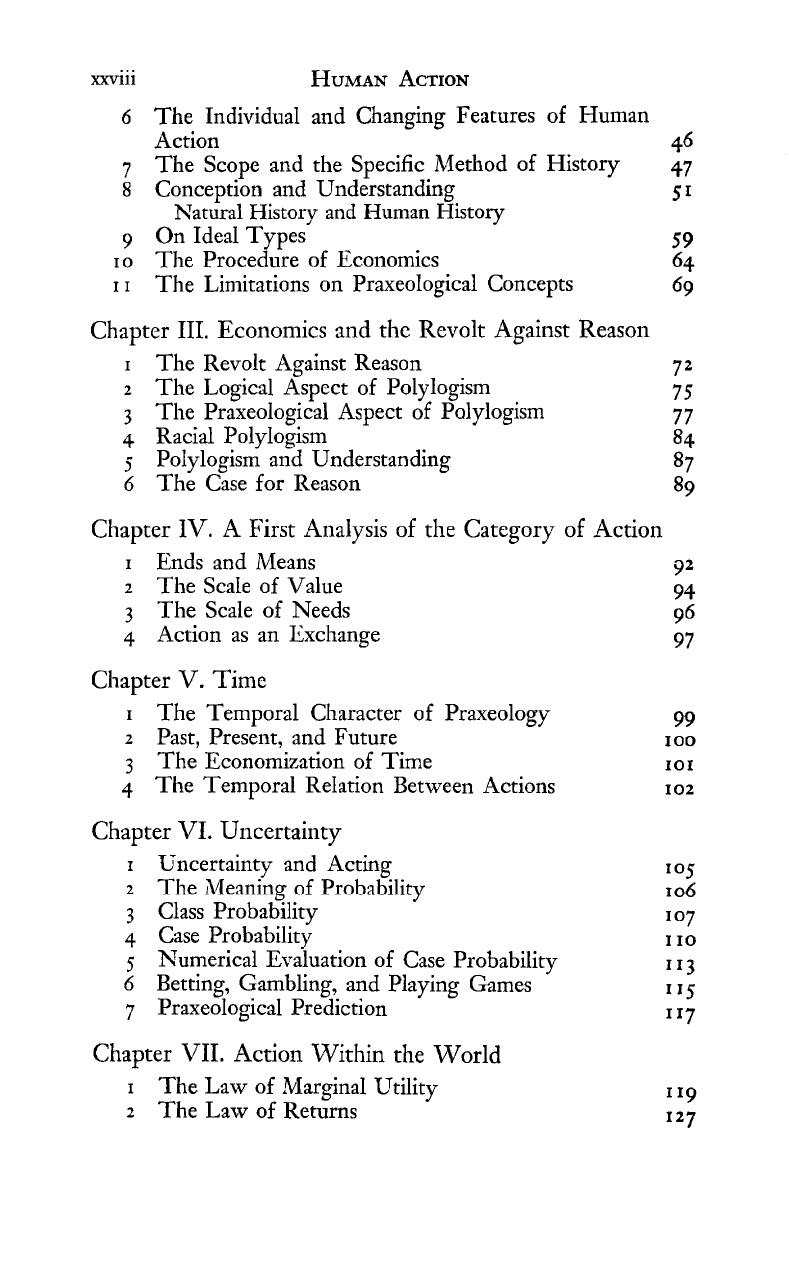

6

The Individual and Changing Features of Human

Action

46

7

The Scope and the Specific Method of History

47

8

Conception and Understanding

5

1

hTatural History and Human History

9

On

Ideal Types

59

10

The Procedure of Economics

64

I

I

The Limitations on Praxeological Concepts

69

Chapter

111.

Economics and the Revolt Against Reason

I

The Revolt Against Reason

72

2

The Logical Aspect of Polylogism

75

3

The Praxeological Aspect of Palylogism

7

7

4

Racial Polylogism

84

j

Polylogism and Understanding

8

7

6

The Case for Reason

89

Chapter

1V.

A First Analysis of the Category of Action

I

Ends and Means

2

The ScaIe of Value

3

The Scale of Needs

4

Action as an Exchange

Chapter

V.

Time

I

The Temporal Character of Praxeology

99

2

Past, Present, and Future

100

3

The Economization of Time

101

4

The Temporal ReIation Between Actions

102

Chapter

VI.

Uncertainty

I

Encertainty and Acting

105

2

The

Meaning

of

Probability

I

e5

3

Class Probability

107

4

Case Probability

I

10

5

Numerical Evaluation of Case Probability

113

6

Betting, Gambling, and Playing Games

115

7

Praxeological Prediction

117

Chapter

VII.

Action Within the World

I

The Law of Marginal Utility

z

The Law of Returns

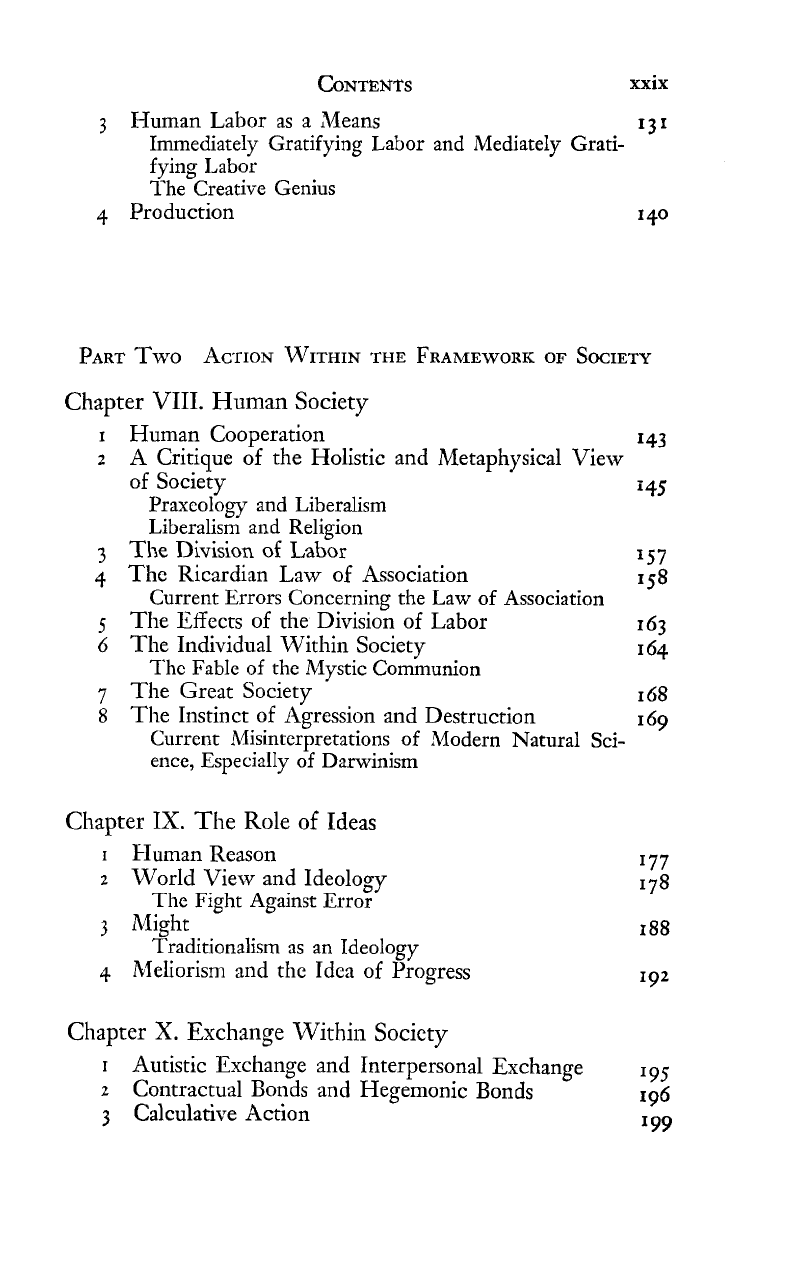

CONTENTS

xxix

3

Human Labor as a Means

13I

Immediately Gratifying Labor and Mediately Grati-

fying Labor

1

he Creative Genius

4

Production

14"

PART

TWO

AC~ION

WITHIN

THE

FRAMEWORK

OF

SOCIETY

Chapter

VIII.

Human Society

I

Human Cooperation

I43

2

A Critique of the Holistic and Metaphysical View

of Society 145

Praxcology and Liberalism

Liberalism and Religion

3

The

Division

of

Labor

157

4

The Ricardian Law of Association

Current Errors Concerning the Law of Association

158

5

The Effects of the Division of Labor

163

6

The Individual Within Society

1

64

Thc Fable of the Mystic Communion

7

The Great Society

I

68

8

The Instinct of Agression

and

Destruction

Currcnt Misinterpretations of Modern Natural Sci-

'69

ence, EspecialIy of Darwinism

Chapter

1X.

The Role of Ideas

I

Human Reason

2

World

View

and Ideology

The

Fight Against Error

3

Might

Traditionalism as an Ideology

4

Meliorism and the Idea of Progress

Chapter

X.

Exchange Within Society

r

Autistic Exchange and Interpersonal Exchange

195

2

Contractual Bonds and Hegemonic Bonds

3

Calculative Action

'96

'99

Chapter

XI.

Valuation Without Calculation

I

The Gradation of the Means

ZOI

2

The Barter-Fiction of the Elementary Theory of

Value and Prices

202

The Theory of Value

and

Socialism

3

The Problem of Economic Calculation

207

4

Economic Calculation and the Market

2

10

Chapter XII.

The

Sphere of Economic Calculation

-

I

The Character of the Monetary Entries

213

2

The Limits of Economic Calculation

215

3

The Changeability of Prices

2

18

4

Stabilization

220

5

The Root of the Stabilization Idea

225

Chapter

XIII.

Monetary Calculation as a Tool of Action

I

Monetary Calculation as a Method of Thinking

230

2

Economic Calculation and the Science of Human

Action

232

Chapter

XIV.

The

Scope

and

Method

of Catallactics

I

The Delimitation of the CataIlactic Problems

233

The Denial of Economics

2

The Method of Imaginary Constructions

237

3

The Pure Market Economy

238

The Maximization of Profits

4

The Autistic Economy

244

5

The State of Rest and the Evenly Rotating Econ-

omy

245

6

The Stationary Economy

251

7

The Integration of Catallactic Functions

252

The Entrepreneurial Function in

the

Stationary

Economy

CONTENTS

Chapter

XV.

The Market

The Characteristics of the Market Economy

258

Capital

2

60

Capitalism 264

The Sovereignty of the Consumers

270

The Metaphorical Employment of the Terminology

of

Political Rule

Competition

273

Freedom

279

Inequality of Wealth and Income

285

Entrepreneurial Profit

and

Loss

2

86

Entrepreneurial Profits and Losses in a Progressing

Economy

292

Some Observations on the Underconsumption Bogey

and on the Purchasing Power Argument

Promoters, Managers, Technicians, and Bureaucrats

300

The Selective Process

308

The Individual and the Market

3x1

Business Propaganda

3'6

The

"Volkswirtschaf

t"

3'9

Chapter

XVI.

Prices

1

The Pricing Process

324

2

Valuation and Appraisement

328

3

The Prices of the Goods of Higher Orders

3 30

A

Limitation on the Pricing of Factors of Production

4

Cost Accounting

336

5

Logical

Catallactics

Versus

Mathematical

Catallactics

347

6 Monopoly Prices

3 54

The Mathematical Treatment of the Theory of

Mo-

nopoly Prices

7

Good Will

376

8

Monopoly of Demand

380

9

Consumption as Affected by Monopoly Prices

381

10

Price Discrimination on the Part of the Seller

385

11

Price Discrimination on the Part of the Buyer

I

2

The Connexity of Prices

388

I

3

Prices

and

Income

388

3

90

14

Prices and Production

391

15

The

Chimera of Nonmarket Prices

3

92