Miller Margaret-Louise. Archaeological Approaches to Technology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

208 Heather M.-L. Miller: Archaeological Approaches to Technology

Indus Valley Tradition Approximate Dates Equivalent Terms in Other Systems

Early Food Producing Era >6500 to 5000

BCE

5000 to 2600

BCE

Neolithic

“Mehrgarh” Phase

Regionalization Era Early Harappan

or

Balakot Phase

Amri Phase

Neolithic

/

Early Chalcolithic

Hakra Phase

Ravi Phase

Kot Diji Phase

Integration Era 2600 to 1900

BCE

Mature Harappan

or

Harappan Phase

Chalcolithic

/

Bronze Age

Localization Era 1900 to 1300

BCE

Late Harappan

or

Punjab Phase

Jhukar Phase

Rangpur Phase

Chalcolithic

/

Bronze Age

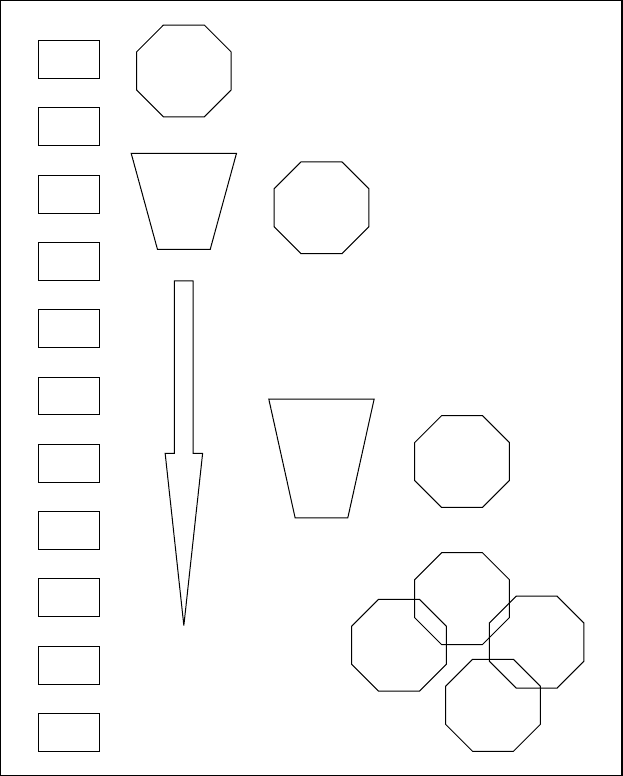

FIGURE 6.2 Chronological systems for the Indus Valley Tradition, with approximate calibrated

radiocarbon dates. (Modified after Shaffer 1992; Kenoyer and Miller 1999.)

The traditional models of centralized state formation are an uneasy fit for

the Indus (Kenoyer 1998a, 1998b; Possehl 1998). There is little of the usual

archaeological evidence for a ruling elite, either secular or religious: no large

temples or palaces, no evidence for a victorious military or an institutional

warehousing system, no rich tombs or monumental art. While we do have

a few public buildings at Indus sites, like the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro,

the Indus “‘monumental architecture” is in many ways the city itself. Rather

than an impressive palace complex, we seem to have a city made up of decent

neighborhoods, albeit with a range of large to small houses. Long before the

Greeks, the people in the Indus region were laying out blocks of housing

developments on a rough grid plan, building large-scale sewage and garbage

disposal systems, and creating truly massive perimeter walls around their city

neighborhoods. Indus art is not monumental but miniature, and it requires a

certain level of cultural knowledge to appreciate it, since its value is as much

about specialized skill and labor as it is about rare materials. The Indus people

shared a cultural style, a weight system, and a script across an area larger

than Egypt and Mesopotamia combined, and traded far beyond this area. But

there is no obvious evidence for deeply divided social hierarchies, no supreme

rulers that we can see. What then was the Indus social and political structure?

A first step in answering this question is to determine how Indus people

were marking their status. Clearly some economic and social divisions did

exist, but the marking systems are different and apparently more subtle than

in other civilizations, as Rissman (1988) suggests through his analysis of

urban Indus burials and hoards, and as Possehl (1998) references in his

Thematic Studies in Technology (Continued) 209

characterization of Indus leadership as “faceless.” Kenoyer (1991; 1998b) has

discussed the social hierarchies implicit in the types of raw materials used to

make red and white beads, and Vidale (2000) and I (H. M.-L. Miller in press-b)

have extended this to other bead types. Vidale and I together (Vidale and Miller

2000) played with the idea that the development of new materials over some

three millennia was related to the changing nature of social status, especially

with the development of cities and complex social and political systems. One

approach has thus been to examine the relationship between markers of Indus

social relations and the development of new materials, particularly the Indus

talc-faience complex.

All three of the earliest urban societies of the Eastern Hemisphere, Egypt,

Mesopotamia, and the Indus, developed complexes of vitreous materials that

include glazed stone and a group of glossy, silica-based materials most often

called “faience,” as described in Chapter 4. The development of these vitreous

materials in these three regions probably represents technological stimulus and

diffusion, with each region aware to some extent of the materials developed

in the other regions, but manufacturing their own objects. There are overlaps

in the production processes and types of materials in the three regions, but

each region seems also to have made its own innovations and followed its own

path of development. For example, only in the Indus was a type of faience

developed that included fragments of talc as well as silica in the body.

The talc-faience complex of materials well represents the long development

of Indus artificial materials, beginning for this complex with the heat treat-

ment of talcose stone in the sixth millennium (after 6000

BCE). A remarkable

property of talc (also called steatite) is that although it is soft and multicolored

in its natural state, when heated to high temperatures (above 1000

C), all

types of talc become hard and many become bright white, even some black

talcs. This striking material transformation may have given talc/steatite a spe-

cial significance for the Indus. Vidale (2000) has speculated, on the basis of

his ethnoarchaeological work in Baluchistan (Vidale and Shar 1991), that the

importance of talc in the Indus bead assemblage may in part be related to its

startling transformation from various colors to a bright white after firing. This

color change may have served as a material illustration or symbol of religious

beliefs. So it is noteworthy that beginning around 6000

BCE in the burials at

the earliest Indus Valley Tradition site of Mehrgarh, there is an increase in

fired talcose beads, which are white in color, in parallel with the decrease

in white shell beads. By the start of the Indus Integration Era around 2600

BCE, shell beads are relatively rare in both burial and non-burial contexts at

numerous Indus sites (Barthélémy de Saizieu and Bouquillon 1994; Kenoyer

1995; Vidale 1995; H. M.-L. Miller in press b). This rarity has nothing to do

with difficulty of access to the raw material, as shell bangles and other shell

objects are quite common. In fact, shell is still the primary material used for

210 Heather M.-L. Miller: Archaeological Approaches to Technology

bangles for Harappan Phase Integration Era burials (Kenoyer 1998a: 144), but

bead ornaments are primarily made from talc in various forms. Thus, shell

continues to hold ritual value in some forms, but fired talc beads replace shell

beads altogether in all contexts. Again, this valuation of talc may have to do

with its transformative quality, something not possible with shell.

Our knowledge of the talc-faience complex bead materials prior to the Indus

Integration Era is based primarily on work done by the French archaeological

project at Mehrgarh and Nausharo (Barthélémy de Saizieu and Bouquillon

1994, 1997; Bouquillon and Barthélémy de Saizieu 1995; Barthélémy de Saizieu

2004). The first talc/steatite beads found at Mehrgarh are unfired, usually with

a natural color of black or dark brown, and alternated with white shell beads. In

the sixth millennium, white-fired talcose beads begin to appear (Figure 6.3). By

the beginning of the fourth millennium, more than 90% of the talc beads from

Mehrgarh were fired white, and the first blue-green silicate glazes on talc beads

are also found at this time. Just prior to and at the beginning of the “Pre-Indus”

periods at Nausharo, from about 3200

BCE onwards, there is an increasing

predominance of discoid forms and tiny sizes in fired talc beads, and a number

of new materials appear, including talcose-faience, siliceous faiences, and

possibly talc paste. These materials continue to be used throughout the Indus

Integration Era (2600–1900

BCE) and have been common finds at most Indus

sites (discussion and references in Kenoyer 1991; Vidale 1992, 2000). Blue-

green glazed talcose stone was used exclusively for beads, while white-surfaced

fired talc was used to make the most common inscribed Indus materials, seals,

tokens, and tablets. The Indus microbeads, only one millimeter in diameter

and length, may have been either individually cut and ground from talcose

stone or produced from a still undefined sintered talc paste mixture, then

fired. Talcose-faience, a material with talcose fragments in a sintered silicate

matrix, may primarily be a transitional material employed in the first periods

of faience manufacture, but the very small number of tests for materials

dating to the Indus Integration Era makes this an entirely open question to

date (see Chapter 4, Vitreous Silicates section). It may equally represent a

material used for particular purposes, and/or of particular symbolism. Siliceous

faience, which turns quartz sand or ground pebbles and a little copper dust

into a brightly glazed blue-green sintered silicate object, was widely used

for bangles, beads and other ornaments, inscribed tablets, inlay pieces, small

vessels, and small figurines or amulets. Classification of the exact material

used to make a particular object is difficult, as they are almost identical in

appearance even under low magnification, and descriptions in the literature

are thus often incomplete or confusing; see Miller (in press-a) for a detailed,

descriptive terminology for the various materials in the Indus talc-faience

complex. These artificial materials are linked not only by their very similar

physical appearances, but also in their overlapping raw material components.

Thematic Studies in Technology (Continued) 211

7000

BCE

6000

5500

5000

4500

3000

4000

3500

2000

2500

6500

Reduction

of

Massive

Talc

Talc

Begins

to be Fired

White

Growing

Exploitation

of

Talc

Talc

Mostly

Fired

White

Glazed

Talc

Siliceous

Faience

Talcose-

Faience

Talc

Micro-beads

Talc

Paste?

FIGURE 6.3 Development of new talcose- and silicate-based materials (talc-faience complex)

in the Indus Valley Tradition. (Data primarily from Mehrgarh-Nausharo studies by Barthélémy

de Saizieu and Bouquillon—see text.)

In addition, they likely had connections during the process of production,

whether through the recycling of by-products such as talc powder or in the

use of similar techniques of production. These diverse talc-faience materials

may have been made in the same workshops.

212 Heather M.-L. Miller: Archaeological Approaches to Technology

All of these vitreous materials require more skill and more specialized

knowledge to produce than beads cut from massive talcose stones, particularly

with the need to perfect paste and glaze compositions and firing techniques.

The new materials also allowed the use of talc and/or quartz powder, and

so the use of waste materials and lower quality talc. This explosion of new

materials is thus a brilliant example of the technical virtuosity of the Indus

craftspeople, and also provides insights into Indus society (Vidale and Miller

2000). “Indus technical virtuosity,” as we defined it, refers to the striking

Indus characteristic of inventing, adopting, modifying, and diffusing complex

techniques across the large Indus region. These techniques were not used to

create monumental objects or large symbols of religious or secular power, but

were used primarily for the production of small ornamental objects, objects

that were worn or otherwise displayed. In our opinion, the small size of these

ornamental objects did not preclude their social importance, particularly for

communicating social roles, and the development and encouragement of Indus

technical virtuosity reflects and is a reflection of strategies of social patterning

from the fourth through second millennia

BCE, or even earlier.

The creation of these many new artificial materials occurs around the time of

the development of the urban, heterogeneous Indus Integration Era social and

political structure. There seem to have been a number of levels of social status

created at this time, rather than just a bipartite division between “commoners”

and “elites.” Looking more broadly, this seems a characteristic not only of the

Indus, but of many of the Western Asian civilizations of the third and second

millennia

BCE. This extended system of social levels would need new methods

of marking or signaling these varying levels of status. One such expanded

status marking system has been suggested for various prehistoric and historic

periods, where an increased use of artificial materials is tied to a widening

demand for status or luxury goods, with the development of a middle-level

elite, a bureaucracy, and/or a wealthy urban class (e.g. McCray 1998; Moorey

1994: 169; Vidale 2000; Vidale and Miller 2000; H. M.-L. Miller in press-b).

These new materials could be employed to create status symbols for such

middle-level classes, allowing an extended hierarchy of status in societies

ranked with increasingly complexity. How can we determine if the case of the

Indus talc-faience materials represents a similar situation, where new materials

are being used to mark an expanding number of social levels? The first step is

to determine the relative value of materials and objects, old and new, natural

and artificial, to create a ranking of the relative value of materials.

DETERMINING RELATIVE VALUE

The relative values of materials and objects is culturally-specific, as researchers

have discussed for a number of situations (e.g., Helms 1993; Lesure 1999).

Thematic Studies in Technology (Continued) 213

This makes it a challenge to identify scales of value in the past, particularly

when we have few historic or oral records as a guide. Furthermore, the eco-

nomic value of materials and objects may be very different from ritual or

status scales of value within the same society; an object of low economic

value may have quite high ritual value. For example, Solometo (2000) dis-

cusses the relative value of materials used by the Hopi to make pigments

for ritual wall paintings, as mentioned in the section on Ritual Technology

at the end of this chapter. For this case, exotic rare materials were highly

valued as pigments, but the value of other objects relied on other associations

besides scarcity, such as color or association with ancestral dwelling places.

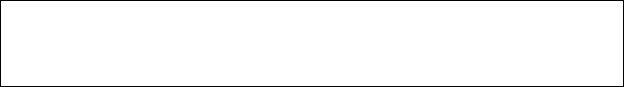

To deal with these complexities, archaeologists must employ a large number

of diverse data sets to assess the relative value of objects and materials, includ-

ing textual and pictorial materials, oral traditions, historical and ethnographic

analogies, the archaeological contexts and archaeological rarity of finished

objects, and evidence for their curation (Figure 6.4). The ambiguity of many

of these sources of data for the Indus is discussed and assessed in Miller

(in press-b).

Technological considerations are also used to assess value, such as the

estimated time of production, often used as a proxy for labor costs. For the

Indus, estimated time of production has been approached through a number

of ethnoarchaeological and experimental projects focused on Indus materials,

such as the stone bead studies discussed in Chapter 3 (e.g., Kenoyer, et al.

1991, 1994; Roux, et al. 1995; Roux and Matarasso 1999; Roux 2000; Vanzetti

and Vidale 1994; Vidale 1995, 2000). The basic idea is that only wealthy

elite can afford the costs involved in craftspeople producing few artifacts over

a long period of time, the labor expense of the object. For example, the

lengthy time involved in drilling hard stone beads, such as agate or carnelian,

would theoretically make them more valuable than softer stone beads that

required less time to create and so less labor cost. However, rather than simply

calculating the times spent on each production stage to measure expense, most

of the Indus studies have placed equal emphasis on specialized skill and/or

knowledge, as is further discussed below. Many studies, well summarized

by Underhill (2002: 6–8), have focused on such status markers created with

significant labor investment, particularly in socially and politically ranked or

middle-range (“chiefdom”) societies.

Texts & Pictures

Oral Traditions

Ethnographic Analogies

Time of Production (Labor Costs)

Difficulty of Procurement

– Access to Materials

– Complexity of Production

Archaeological Context

Archaeological Rarity

Curation

FIGURE 6.4 Data sets used by archaeologists for the assessment of value.

214 Heather M.-L. Miller: Archaeological Approaches to Technology

Another technological consideration used in the assessment of relative value

is the estimated difficulty of procurement (Figure 6.4, far right). This category

includes both the procurement of raw materials from which the objects

are made, and the complexity of production, involving specialized knowledge,

skills, and tools. Many archaeological models of the relationship between

status and display or “prestige” goods focus on the former, primarily the pro-

curement of exotic raw materials (e.g., Helms 1993; Bellina 2003), as exotic

raw materials are often common component of status items. Both for status

based on intensive labor investment and status based on exotic raw materials,

ornament styles are a particularly useful method of marking social information

through display (Wobst 1977). For the Indus, it is especially important to also

include complexity of production in any assessment of status markers, given

the many complex craft traditions found in the Indus with the creation of new

artificial materials such as faience, fired talc, metal alloys, and stoneware. The

timing of the development of these new materials is very suggestive, occurring

at the same time as there seem to be increasing numbers and types of social

classes.

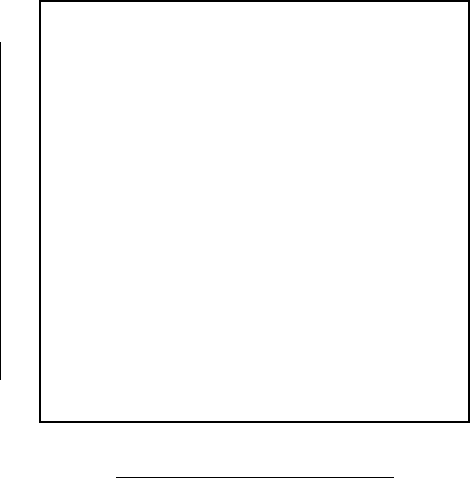

Several recent Indus studies have focused on these two technologically-

related data sets for assessing relative value, primarily on both aspects of the

relative difficulty of procurement but also indirectly on labor costs. Figure 6.5

is a diagram based on earlier charts used by Kenoyer (1992) to represent

relative types of control over different craft industries, and charts used by

Vidale (1992) to assess the relative value of object types made from different

materials. In this expected relative value diagram, the relative accessibility of

the raw materials needed to produce a given type of object is assessed and

graphed along the horizontal (x) axis, while the vertical (y) axis represents

the assessment of the relative complexity of production. Neither assessment

is a straightforward procedure. For example, the assessment of the difficulty

of accessing raw materials must allow not only for the physical distance

to sources, but also the environmental conditions and the social situations

that affect the ease with which craft producers can obtain these materials.

A metal ore source accessible by river transport may be more accessible

to producers than a nearer source accessible only by walking. Or a lithic

or mineral source on one end of a seasonal pastoral round may be more

accessible to producers on the other end of the round if they have trading

relations with the pastoralists. For the vertical (y) axis, the relative complexity

of the production sequence, we need to have some measure of the degree of

specialized knowledge needed to produce certain objects, not to mention the

probable restriction of such knowledge, in order to estimate the difficulty of

production for each type of object. The information needed to rate the relative

complexity of production involves at minimum the construction of production

process sequences for each object, as described in Chapters 3 and 4, detailing

Thematic Studies in Technology (Continued) 215

Difficulty of Access to Raw Materials

LOW MEDIUM HIGH

LOW MEDIUM HIGH

Relative Degree of Complexity of Production

Stoneware

Bangles

Simple

Stone Beads

Fired Talc

Beads

Bleached

Carnelian Beads

Faiences,

Glazed Objects

Simple

Terracotta Objects

Bone Tools

Elaborate

Metal Objects

Marine Shell

Ornaments

Basketry

Complex

Terracotta

Vessels

FIGURE 6.5 Expected relative value diagram; this example uses Indus Integration Era

object/material types.

the number of production steps and tools, and an indirect or direct estimate

of the time needed for production. But this is not enough to rate the relative

complexity of production; an assessment of the technical knowledge involved

may be even more important (e.g., Wright 1991).

Thus, diagrams like Figure 6.5 approximate the expected relative value of

objects, as they explicitly combine estimations of the relative difficulty of

access to materials and estimations of the relative complexity of production,

the later usually also implicitly including labor costs. All of these variables are

extremely difficult to measure archaeologically. These diagrams are further

simplified in that the type of object being produced is not specified, and not

all objects follow the same production sequence even if they are created from

the same raw materials. However, such diagrams can be used to assess the

expected relative values of objects on a broad scale; see Vidale and Miller

(2000) for an example. These diagrams are especially valuable in that they

allow the assignment of expected relative value to objects produced by one

craft versus another. For example, clay suitable for the production of all types

of fired clay objects is universally available in the Indus floodplains. Deposits

of stone and metal ore are much more restricted in distribution, to the edges

216 Heather M.-L. Miller: Archaeological Approaches to Technology

of the Indus region. Strictly in terms of raw material access, objects of clay

should thus have been less valuable than objects of talc or agate or copper.

However, when the relative value imparted by the complexity of producing an

object from these raw materials is added, relative values may change. For the

fired clay crafts, complexity of production ranges from the simple techniques

used to make and fire terracotta “cakes”; to the more uniformly processed

and fired terracotta bangles and figurines; to wheel-thrown and elaborately

painted pottery; to the extremely complex firing regimes of stoneware bangle

production, so called because they were fired to the point of sintering and

break like flint or obsidian. All of these objects are made with the same raw

materials; any difference in expected relative value lies in the complexity of

their production.

In sum, the schematic organization of data shown in Figure 6.5 simplifies

the depiction of the very complex data involved, much as graphs and statistical

test results are used to simplify the portrayal of complex numerical data.

As noted, the diagram is particularly useful as it allows the comparison of

expected relative value for objects produced by different crafts. These diagrams

can also be used to examine changes in value for material culture assemblages

through time (Vidale and Miller 2000). Furthermore, these production-based

assessments of the expected relative values of objects (Figure 6.4, column 3)

can be compared with relative value assessments based on archaeological

data such as context, rarity and curation (Figure 6.4, column 2), and/or

value assessments based on ethnographic parallels or historical documents

(Figure 6.4, column 1). These comparisons between value assessments based

on different types of data set up a system of cross-checks for the difficult task

of appraising ancient values.

For example, Indus Integration Era stoneware bangles, produced from a

widely accessible material but with a very complex technology, were higher

in value than copper bangles, which were of imported materials but generally

produced in a relatively simple manner. Such an assessment is supported not

only by these expected relative values, but also by the archaeological evidence

on context and rarity. Stoneware bangles have a very restricted distribution,

being found only at the largest sites, an unusual restriction of consumption for

the Indus. They also had a very restricted production, as they were produced

only at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, and possibly one other site (Blackman and

Vidale 1992). In addition, most or perhaps all of these stoneware bangles had

individual inscriptions. Furthermore, the stoneware bangles provide sound

evidence that they were valued for the material itself, rather than the finished

appearance of the object. In spite of their very careful and elaborate manu-

facturing process, there is little attention to their surface finishing. Breakage

scars left on some bangles from sticking during firing were only roughly

ground down, leaving them quite visible (Vidale 1990). While many or most

Thematic Studies in Technology (Continued) 217

were inscribed, the inscriptions are roughly scratched, in great contrast to the

highly polished finish left by the manufacturing process (Kenoyer 1994). The

value in these objects seems to have been based on the elaborate production

required to create this material, rather than on details of perfect finish—the

type of skill valued may be mastery of the deep transformation of clay to

“stone,” not perfection of surface. For the Indus, it is also possible that a

portion of the value given to stoneware bangles, like talc and faience objects,

lies in their transformation by fire to a new artificial material, as I will further

discuss below.

For the specific case of Indus talc-faience materials, Vidale and I (Vidale

and Miller 2000) placed them as objects made from materials not so diffi-

cult to access, but requiring quite high levels of technological elaboration

(Figure 6.5). These materials range from low to medium difficulty of access, as

the talcose stone and quartz minerals needed were located in several regions

around the immediate edges of the Indus Valley, so that they could likely

be procured in sufficient amounts in a steady supply through reliable trading

connections (Law 2005, 2006). But all of these materials involved production

processes of many steps and a great deal of specialized knowledge, resulting

in a high rating for technological elaboration. This combination, we thought,

made them ideal status markers for the growing middle levels of status in the

urbanizing Indus civilization. These ornaments and other display items, made

of heat-transformed talcs and/or various faiences, could function as symbols

of status for the growing ranks of merchants, workshop owners, and bureau-

crats in trade, craft production, and urban management during the Indus

Integration Era (Vidale 2000; Vidale and Miller 2000). Moorey (1994: 169)

has similarly suggested that Mesopotamian faience and glass production was

stimulated by “widening social demand, rather than depredation in the richer

sections of society.”

SOCIAL RELATIONS AND THE RELATIVE VALUE

OF

INDUS TALC-FAIENCE MATERIALS

Was this suggestion correct? What was the relationship between the demand

for new artificial materials and the increasing diversification of social and

economic classes in the Indus? This is a point that turned out to be rather

involved but highly revealing for the Indus, and is especially interesting in

light of some unusual aspects of Indus material use in comparison to the

contemporaneous early civilizations of the Near East and Egypt, particularly

the relative absence of lapis lazuli and the prevalence of talc/steatite. As

outlined below, for some cases, such as red with white colored beads, the

proposal that new artificial materials were employed to fill a need for more