McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 9

The Aggregate Expenditures Model

183

Limitations of the Model

This chapter’s analysis demonstrates the power of the ag-

gregate expenditures model to explain how the economy

works, how recessions or depressions can occur, and how

demand-pull inflation can arise. But this model has five

well-known limitations:

• It does not show price-level changes. The model can

account for demand-pull inflation, as in Figure 9.7 b,

but it does not indicate how much the price level will

rise when aggregate expenditures are excessive relative

to the economy’s capacity. The aggregate expenditures

model has no way of measuring the rate of inflation.

• It ignores premature demand-pull inflation. Mild

demand-pull inflation can occur before an economy

reaches its full-employment level of output. The

aggregate expenditures model does not explain why

that can happen.

• It limits real GDP to the full-employment level of

output . For a time an actual economy can expand be-

yond its full-employment real GDP. The aggregate

expenditures model does not allow for that possibility.

• It does not deal with cost-push inflation. We know

from Chapter 7 that there are two general types of

inflation: demand-pull inflation and cost-push infla-

tion. The aggregate expenditures model does not

address cost-push inflation.

• It does not allow for “self-correction.” In reality, the

economy contains some internal features that, given

enough time, may correct a recessionary expenditure

gap or an inflationary expenditure gap. The aggre-

gate expenditures model does not contain those

features.

In subsequent chapters we remedy these limitations while

preserving the many valuable insights of the aggregate ex-

penditures model.

Summary

1. For a private closed economy the equilibrium level of GDP

occurs when aggregate expenditures and real output are

equal or, graphically, where the C I

g

line intersects the 45°

line. At any GDP greater than equilibrium GDP, real output

will exceed aggregate spending, resulting in unplanned in-

vestment in inventories and eventual declines in output and

income (GDP). At any below-equilibrium GDP, aggregate

expenditures will exceed real output, resulting in unplanned

disinvestment in inventories and eventual increases in GDP.

2. At equilibrium GDP, the amount households save (leakages)

and the amount businesses plan to invest (injections) are

equal. Any excess of saving over planned investment will

cause a shortage of total spending, forcing GDP to fall. Any

excess of planned investment over saving will cause an

excess of total spending, inducing GDP to rise. The change

in GDP will in both cases correct the discrepancy between

saving and planned investment.

3. At equilibrium GDP, there are no unplanned changes in

inventories. When aggregate expenditures diverge from real

GDP, an unplanned change in inventories occurs.

Unplanned increases in inventories are followed by a cut-

back in production and a decline of real GDP. Unplanned

decreases in inventories result in an increase in production

and a rise of GDP.

4. Actual investment consists of planned investment plus un-

planned changes in inventories and is always equal to saving.

5. A shift in the investment schedule (caused by changes in

expected rates of return or changes in interest rates) shifts

the aggregate expenditures curve and causes a new equilib-

rium level of real GDP. Real GDP changes by more than

the amount of the initial change in investment. This multi-

plier effect (GDP/ I

g

) accompanies both increases and

decreases in aggregate expenditures and also applies to

changes in net exports ( X

n

) and government purchases ( G ).

6. The net export schedule in the model of the open economy

relates net exports (exports minus imports) to levels of real

GDP. For simplicity, we assume that the level of net exports

is the same at all levels of real GDP.

7. Positive net exports increase aggregate expenditures to a

higher level than they would if the economy were “closed” to

international trade. Negative net exports decrease aggregate

expenditures relative to those in a closed economy, decreas-

ing equilibrium real GDP by a multiple of their amount.

Increases in exports or decreases in imports have an expan-

sionary effect on real GDP, while decreases in exports or in-

creases in imports have a contractionary effect.

8. Government purchases in the model of the mixed economy

shift the aggregate expenditures schedule upward and raise

GDP.

9. Taxation reduces disposable income, lowers consumption

and saving, shifts the aggregate expenditures curve down-

ward, and reduces equilibrium GDP.

10. In the complete aggregate expenditures model, equilibrium

GDP occurs where C

a

I

g

X

n

G GDP. At the equi-

librium GDP, leakages of after-tax saving ( S

a

), imports ( M ),

and taxes ( T ) equal injections of investment ( I

g

), exports ( X ),

and government purchases ( G ): S

a

M T I

g

X

n

G .

Also, there are no unplanned changes in inventories.

mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 183mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 183 8/21/06 4:22:13 PM8/21/06 4:22:13 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART THREE

Macroeconomic Models and Fiscal Policy

184

11. The equilibrium GDP and the full-employment GDP may

differ. A recessionary expenditure gap is the amount by which

aggregate expenditures at the full-employment GDP fall short

of those needed to achieve the full-employment GDP. This

gap produces a negative GDP gap (actual GDP minus poten-

tial GDP). An inflationary expenditure gap is the amount by

which aggregate expenditures at the full-employment GDP

exceed those just sufficient to achieve the full-employment

GDP. This gap causes demand-pull inflation.

12. The aggregate expenditures model provides many insights

into the macroeconomy, but it does not (a) show price-level

changes, (b) account for premature demand-pull inflation,

(c) allow for real GDP to temporarily expand beyond the

full-employment output, (d) account for cost-push inflation,

or (e) allow for partial or full “self-correction” from a reces-

sionary expenditure gap or an inflationary expenditure gap.

1. What is an investment schedule and how does it differ from

an investment demand curve?

2. KEY QUESTION Assuming the level of investment is

$16 billion and independent of the level of total output,

complete the accompanying table and determine the equi-

librium levels of output and employment in this pri-

vate closed economy. What are the sizes of the MPC and

MPS?

Terms and Concepts

planned investment

investment schedule

aggregate expenditures schedule

equilibrium GDP

leakage

injection

unplanned changes in inventories

net exports

lump-sum tax

recessionary expenditure gap

inflationary expenditure gap

Study Questions

actual investment? Use the concept of unplanned investment

to explain adjustments toward equilibrium from both the

$380 billion and the $300 billion levels of domestic output.

4. Why is saving called a leakage ? Why is planned investment

called an injection ? Why must saving equal planned invest-

ment at equilibrium GDP in the private closed economy?

Are unplanned changes in inventories rising, falling, or con-

stant at equilibrium GDP? Explain.

5. What effect will each of the changes listed in Study Ques-

tion 3 of Chapter 8 have on the equilibrium level of GDP in

the private closed economy? Explain your answers.

6. By how much will GDP change if firms increase their invest-

ment by $8 billion and the MPC is .80? If the MPC is .67?

7. Depict graphically the aggregate expenditures model for a

private closed economy. Now show a decrease in the aggre-

gate expenditures schedule and explain why the decline in

real GDP in your diagram is greater than the initial decline

in aggregate expenditures. What would be the ratio of

a decline in real GDP to the initial drop in aggregate

expenditures if the slope of your aggregate expenditures

schedule was .8?

8. Suppose that a certain country has an MPC of .9 and a real

GDP of $400 billion. If its investment spending decreases

by $4 billion, what will be its new level of real GDP?

9.

KEY QUESTION The data in columns 1 and 2 in the accom-

panying table are for a private closed economy:

a. Use columns 1 and 2 to determine the equilibrium GDP

for this hypothetical economy.

b. Now open up this economy to international trade by

including the export and import figures of columns 3

Possible Real Domestic

Levels of Output

Employment, (GDP DI), Consumption, Saving,

Millions Billions Billions Billions

40 $240 $244 $ _____

45 260 260 _____

50 280 276 _____

55 300 292 _____

60 320 308 _____

65 340 324 _____

70 360 340 _____

75 380 356 _____

80 400 372 _____

3. Using the consumption and saving data in question 2 and

assuming investment is $16 billion, what are saving and

planned investment at the $380 billion level of domestic

output? What are saving and actual investment at that level?

What are saving and planned investment at the $300 billion

level of domestic output? What are the levels of saving and

mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 184mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 184 8/21/06 4:22:13 PM8/21/06 4:22:13 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 9

The Aggregate Expenditures Model

185

and 4. Fill in columns 5 and 6 and determine the

equilibrium GDP for the open economy. Explain why

this equilibrium GDP differs from that of the closed

economy.

c. Given the original $20 billion level of exports, what

would be net exports and the equilibrium GDP if im-

ports were $10 billion greater at each level of GDP?

d. What is the multiplier in this example?

10. Assume that, without taxes, the consumption schedule of an

economy is as follows:

12. KEY QUESTION Refer to columns 1 and 6 in the table for

question 9. Incorporate government into the table by

assuming that it plans to tax and spend $20 billion at each

possible level of GDP. Also assume that the tax is a personal

tax and that government spending does not induce a shift in

the private aggregate expenditures schedule. Compute and

explain the change in equilibrium GDP caused by the

addition of government.

13.

KEY QUESTION Refer to the table below in answering the

questions that follow:

a. If full employment in this economy is 130 million, will

there be an inflationary expenditure gap or a recessionary

expenditure gap? What will be the consequence of this

gap? By how much would aggregate expenditures in

column 3 have to change at each level of GDP to elimi-

nate the inflationary expenditure gap or the recessionary

expenditure gap? Explain. What is the multiplier in this

example?

b. Will there be an inflationary expenditure gap or a reces-

sionary expenditure gap if the full-employment level of

output is $500 billion? Explain the consequences. By

how much would aggregate expenditures in column 3

have to change at each level of GDP to eliminate the

gap? What is the multiplier in this example?

c. Assuming that investment, net exports, and government

expenditures do not change with changes in real GDP, what

are the sizes of the MPC, the MPS, and the multiplier?

a. Graph this consumption schedule and determine the

MPC.

b. Assume now that a lump-sum tax is imposed such that

the government collects $10 billion in taxes at all levels

of GDP. Graph the resulting consumption schedule, and

compare the MPC and the multiplier with those of the

pretax consumption schedule.

11. Explain graphically the determination of equilibrium GDP

for a private economy through the aggregate expenditures

model. Now add government purchases (any amount you

choose) to your graph, showing its impact on equilibrium

GDP. Finally, add taxation (any amount of lump-sum tax

that you choose) to your graph and show its effect on equi-

librium GDP. Looking at your graph, determine whether

equilibrium GDP has increased, decreased, or stayed the

same given the sizes of the government purchases and taxes

that you selected.

(1) (2) (3)

Possible Levels Real Domestic Aggregate Expenditures

of Employment, Output, (C

a

I

g

X

n

G),

Millions Billions Billions

90 $500 $520

100 550 560

110 600 600

120 650 640

130 700 680

GDP, Consumption,

Billions Billions

$100 $120

200 200

300 280

400 360

500 440

600 520

700 600

(1) (2) (6)

Real Domestic Aggregate (5) Aggregate

Output Expenditures, Private (3) (4) Net Expenditures, Private

(GDP DI), Closed Economy, Exports, Imports, Exports, Open Economy,

Billions Billions Billions Billions Billions Billions

$200 $240 $20 $30 $ ______ $ ______

250 280 20 30 ______ ______

300 320 20 30 ______ ______

350 360 20 30 ______ ______

400 400 20 30 ______ ______

450 440 20 30 ______ ______

500 480 20 30 ______ ______

550 520 20 30 ______ ______

mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 185mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 185 8/21/06 4:22:13 PM8/21/06 4:22:13 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART THREE

Macroeconomic Models and Fiscal Policy

186

14. ADVANCED ANALYSIS Assume that the consumption

schedule for a private open economy is such that consump-

tion C 50 0.8 Y . Assume further that planned invest-

ment I

g

and net exports X

n

are independent of the level of

real GDP and constant at I

g

30 and X

n

10. Recall also

that, in equilibrium, the real output produced ( Y ) is equal to

aggregate expenditures: Y C I

g

X

n

.

a. Calculate the equilibrium level of income or real GDP

for this economy.

b. What happens to equilibrium Y if I

g

changes to 10? What

does this outcome reveal about the size of the multiplier?

15. Answer the following questions, which relate to the aggre-

gate expenditures model:

a. If C

a

is $100, I

g

is $50, X

n

is $10, and G is $30, what is

the economy’s equilibrium GDP?

b. If real GDP in an economy is currently $200, C

a

is $100,

I

g

is $50, X

n

is $10, and G is $30, will the economy’s

real GDP rise, fall, or stay the same?

c. Suppose that full-employment (and full-capacity) output

in an economy is $200. If C

a

is $150, I

g

is $50, X

n

is $10,

and G is $30, what will be the macroeconomic result?

16.

LAST WORD What is Say’s law? How does it relate to the

view held by classical economists that the economy gener-

ally will operate at a position on its production possibilities

curve (Chapter 1)? Use production possibilities analysis to

demonstrate Keynes’ view on this matter.

1.

THE MULTIPLIER—CALCULATING HYPOTHETI-

CAL CHANGES IN GDP

Go to the Bureau of Economic

Analysis at www.bea.gov , and use the BEA interactivity

feature to select National Income and Product Account

Tables. Then find Table 1.1, which contains the most re-

cent values for GDP C

a

I

g

G ( X M ). Assume

that the MPC is .75 and that, for each of the following, the

values of the initial variables are those you just discovered.

Determine the new value of GDP if, other things equal, ( a )

investment increased by 5 percent, ( b ) imports increased by

5 percent while exports increased by 5 percent, ( c ) con-

sumption increased by 5 percent, and ( d ) government

spending increased by 5 percent. Which of the changes,

( a ) through ( d ), caused the greatest change in GDP in abso-

lute dollars?

2.

GDP GAP AND EXPENDITURE GAP The St. Louis

Federal Reserve Bank at www.research.stlouisfed.org/

fred2 provides data on both real GDP (chained 2000

dollars) and real potential GDP for the United States. Both

sets of data are located as links under “Gross Domestic

Product and Components.” What was potential GDP for

the third quarter of 2001? What was the actual level of real

GDP for that quarter? What was the size difference between

the two—the negative GDP gap? If the multiplier was 2 in

that period, what was the size of the economy’s recessionary

expenditure gap?

Web-Based Questions

mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 186mcc26632_ch09_165-186.indd 186 8/21/06 4:22:13 PM8/21/06 4:22:13 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

Aggregate Demand and

Aggregate Supply

In early 2000, Alan Greenspan, then chair of the Federal Reserve, made the following statement:

Through the so-called wealth effect, [recent stock market gains] have tended to foster increases in

aggregate demand beyond the increases in supply. It is this imbalance . . . that contains the poten-

tial seeds of rising inflationary . . . pressures that could undermine the current expansion. Our goal

[at the Federal Reserve] is to extend the expansion by containing its imbalances and avoiding the

very recession that would complete the business cycle.

1

Although the Federal Reserve held inflation in check, it did not accomplish its goal of extending the

decade-long economic expansion. In March 2001 the U.S. economy experienced a recession and the

1

Alan Greenspan, speech to the New York Economics Club, Jan. 13, 2000.

10

IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL LEARN:

• About aggregate demand (AD) and the factors that

cause it to change.

• About aggregate supply (AS) and the factors that

cause it to change.

• How AD and AS determine an economy’s

equilibrium price level and level of real GDP.

• How the AD-AS model explains periods of

demand-pull inflation, cost-push inflation, and

recession.

mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 187mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 187 8/21/06 4:51:05 PM8/21/06 4:51:05 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART THREE

Macroeconomic Models and Fiscal Policy

188

Aggregate Demand

Aggregate demand is a schedule or curve that shows the

amounts of real output (real GDP) that buyers collectively

desire to purchase at each possible price level. The rela-

tionship between the price level (as measured by the GDP

price index) and the amount of real GDP demanded is in-

verse or negative: When the price level rises, the quantity

of real GDP demanded decreases; when the price level

falls, the quantity of real GDP demanded increases.

Aggregate Demand Curve

The inverse relationship between the price level and real

GDP is shown in Figure 10.1 , where the aggregate de-

mand curve AD slopes downward, as does the demand

curve for an individual product.

Why the downward slope? The explanation is not the

same as that for why the demand for a single product

slopes downward. That explanation centered on the

income effect and the substitution effect. When the price

of an individual product falls, the consumer’s (constant)

nominal income allows a larger purchase of the product

(the income effect). And, as price falls, the consumer

wants to buy more of the product because it becomes

relatively less expensive than other goods (the substitu-

tion effect).

But these explanations do not work for aggregates. In

Figure 10.1 , when the economy moves down its aggregate

demand curve, it moves to a lower general price level. But

our circular flow model tells us that when consumers pay

lower prices for goods and services, less nominal income

flows to resource suppliers in the form of wages, rents, in-

terest, and profits. As a result, a decline in the price level

does not necessarily mean an increase in the nominal in-

come of the economy as a whole. Thus, a decline in the

price level need not produce an income effect, where more

output is purchased because lower prices leave buyers with

greater real income.

Similarly, in Figure 10.1 prices in general are falling as

we move down the aggregate demand curve, so the ratio-

nale for the substitution effect (where more of a specific

product is purchased because it becomes cheaper relative

to all other products) is not applicable. There is no overall

substitution effect among domestically produced goods

when the price level falls.

If the conventional substitution and income effects do

not explain the downward slope of the aggregate demand

curve, what does? That explanation rests on three effects

of a price-level change.

Real-Balances Effect A change in the price level

produces a real-balances effect . Here is how it works: A

higher price level reduces the real value or purchasing

power of the public’s accumulated savings balances. In par-

ticular, the real value of assets with fixed money values,

such as savings accounts or bonds, diminishes. Because a

higher price level erodes the purchasing power of such as-

sets, the public is poorer in real terms and will reduce its

FIGURE 10.1 The aggregate demand curve. The

downsloping aggregate demand curve AD indicates an inverse (or negative)

relationship between the price level and the amount of real output purchased.

AD

0

Price level

Real domestic output, GDP

Aggregate

demand

expansionary phase of the business cycle ended. Recovery and economic expansion resumed in 2002

and picked up considerable strength in 2003, 2004, and 2005.

We will say more about recession and expansion later. Our immediate focus is the terminology in the

Greenspan quotation, which is precisely the language of the aggregate demand–aggregate supply

model (AD-AS model). The AD-AS model—the subject of this chapter—enables us to analyze

changes in real GDP and the price level simultaneously. The AD-AS model therefore provides keen in-

sights on inflation, recession, unemployment, and economic growth. In later chapters, we will see that

it also explains the logic of macroeconomic stabilization policies, such as those implied by Greenspan.

188

mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 188mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 188 8/21/06 4:51:08 PM8/21/06 4:51:08 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 10

Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply

189

spending. A household might buy a new

car or a plasma TV if the purchasing power

of its financial asset balances is, say,

$50,000. But if inflation erodes the pur-

chasing power of its asset balances to

$30,000, the household may defer its pur-

chase. So a higher price level means less

consumption spending.

Interest-Rate Effect The aggregate demand curve

also slopes downward because of the interest-rate effect .

When we draw an aggregate demand curve, we assume that

the supply of money in the economy is fixed. But when the

price level rises, consumers need more money for purchases

and businesses need more money to meet their payrolls and

to buy other resources. A $10 bill will do when the price of

an item is $10, but a $10 bill plus a $1 bill is needed when

the item costs $11. In short, a higher price level increases

the demand for money. So, given a fixed supply of money,

an increase in money demand will drive up the price paid

for its use. That price is the interest rate.

Higher interest rates curtail investment spending and

interest-sensitive consumption spending. Firms that expect

a 6 percent rate of return on a potential purchase of capital

will find that investment potentially profitable when the in-

terest rate is, say, 5 percent. But the investment will be un-

profitable and will not be made when the interest rate has

risen to 7 percent. Similarly, consumers may decide not to

purchase a new house or new automobile when the interest

rate on loans goes up. So, by increasing the demand for

money and consequently the interest rate, a higher price

level reduces the amount of real output demanded.

Foreign Purchases Effect The final reason why

the aggregate demand curve slopes downward is the for-

eign purchases effect . When the U.S. price level rises

relative to foreign price levels (and exchange rates do not

respond quickly or completely), foreigners buy fewer U.S.

goods and Americans buy more foreign goods. Therefore,

U.S. exports fall and U.S. imports rise. In short, the rise in

the price level reduces the quantity of U.S. goods de-

manded as net exports.

These three effects, of course, work in the opposite

direction for a decline in the price level. Then the quan-

tity demanded of consumption goods, investment goods,

and net exports rises.

Changes in Aggregate Demand

Other things equal, a change in the price level will change

the amount of aggregate spending and therefore change

the amount of real GDP demanded by the economy.

Movements along a fixed aggregate demand curve repre-

sent these changes in real GDP. However, if one or more

of those “other things” change, the entire aggregate de-

mand curve will shift. We call these other things determi-

nants of aggregate demand or, less formally, aggregate

demand shifters . They are listed in Figure 10.2 .

Changes in aggregate demand involve two components:

• A change in one of the determinants of aggregate

demand that directly changes the amount of real

GDP demanded.

• A multiplier effect that produces a greater ultimate

change in aggregate demand than the initiating

change in spending.

In Figure 10.2 , the full rightward shift of the curve

from AD

1

to AD

2

shows an increase in aggregate de-

mand, separated into these two components. The hori-

zontal distance between AD

1

and the broken curve to its

right illustrates an initial increase in spending, say, $5 bil-

lion of added investment. If the economy’s MPC is .75,

for example, then the simple multiplier is 4. So the ag-

gregate demand curve shifts rightward from AD

1

to

AD

2

—four times the distance between AD

1

and the bro-

ken line. The multiplier process magnifies the initial

change in spending into successive rounds of new con-

sumption spending. After the shift, $20 billion ( $5 4)

of additional real goods and services are demanded at

each price level.

Similarly, the leftward shift of the curve from AD

1

to

AD

3

shows a decrease in aggregate demand, the lesser

amount of real GDP demanded at each price level. It also

involves the initial decline in spending (shown as the hori-

zontal distance between AD

1

and the dashed line to its

left), followed by multiplied declines in consumption

spending and the ultimate leftward shift to AD

3

.

Let’s examine each of the determinants of aggregate

demand listed in Figure 10.2 .

Consumer Spending

Even when the U.S. price level is constant, domestic

consumers may alter their purchases of U.S.-produced

real output. If those consumers decide to buy more output

at each price level, the aggregate demand curve will shift

to the right, as from AD

1

to AD

2

in Figure 10.2 . If they

decide to buy less output, the aggregate demand curve will

shift to the left, as from AD

1

to AD

3

.

Several factors other than a change in the price level

may change consumer spending and therefore shift the

aggregate demand curve. As Figure 10.2 shows, those

factors are real consumer wealth, consumer expectations,

household debt, and taxes. Because our discussion here

parallels that of Chapter 8, we will be brief.

O 10.1

Real-balances

effect

mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 189mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 189 8/21/06 4:51:08 PM8/21/06 4:51:08 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART THREE

Macroeconomic Models and Fiscal Policy

190

Consumer Wealth Consumer wealth includes

both financial assets such as stocks and bonds and physical

assets such as houses and land. A sharp increase in the

real value of consumer wealth (for example, because of a

rise in stock market values) prompts people to save less

and buy more products. The resulting increase in con-

sumer spending—called the wealth effect —will shift the

aggregate demand curve to the right. In contrast, a major

decrease in the real value of consumer wealth at each

price level will reduce consumption spending (a negative

wealth effect) and thus shift the aggregate demand curve

to the left.

Consumer Expectations Changes in expecta-

tions about the future may alter consumer spending.

When people expect their future real incomes to rise,

they tend to spend more of their current incomes. Thus

current consumption spending increases (current saving

falls), and the aggregate demand curve shifts to the right.

Similarly, a widely held expectation of surging inflation

in the near future may increase aggregate demand today

because consumers will want to buy products before their

prices escalate. Conversely, expectations of lower future

income or lower future prices may reduce current con-

sumption and shift the aggregate demand curve to

the left.

Household Debt An existing aggregate demand

curve assumes a constant level of household debt. Increased

household debt enables consumers collectively to increase

their consumption spending. That shifts the aggregate

demand curve to the right. Alternatively, when consumers

reduce their household debt, both consumption spending

and aggregate demand decline.

Personal Taxes A reduction in personal income tax

rates raises take-home income and increases consumer

purchases at each possible price level. Tax cuts shift the

aggregate demand curve to the right. Tax increases reduce

consumption spending and shift the curve to the left.

Investment Spending

Investment spending (the purchase of capital goods) is a

second major determinant of aggregate demand. A decline

in investment spending at each price level will shift the

aggregate demand curve to the left. An increase in invest-

ment spending will shift it to the right. In Chapter 8 we

saw that investment spending depends on the real interest

rate and the expected return from the investment.

Real Interest Rates Other things equal, an in-

crease in real interest rates will lower investment spend-

ing and reduce aggregate demand. We are not referring

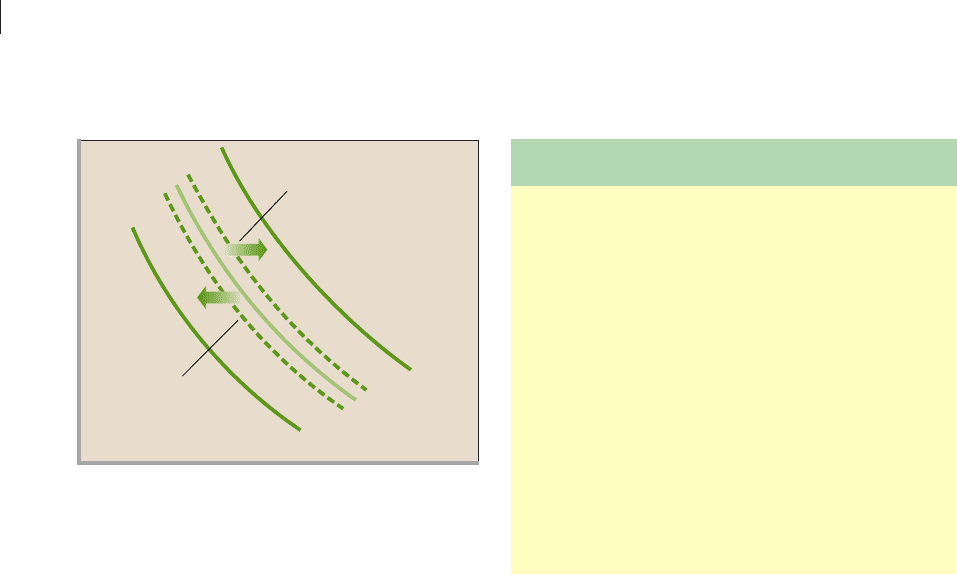

FIGURE 10.2 Changes in aggregate demand. A change in one or more of the listed determinants of aggregate demand will shift the aggregate

demand curve. The rightward shift from AD

1

to AD

2

represents an increase in aggregate demand; the leftward shift from AD

1

to AD

3

shows a decrease in aggregate

demand. The vertical distances between AD

1

and the dashed lines represent the initial changes in spending. Through the multiplier effect, that spending produces

the full shifts of the curves.

AD

3

AD

1

AD

2

Decrease in

aggregate

demand

Increase in

aggregate

demand

0

Price level

Real domestic output, GDP

Determinants of Aggregate Demand: Factors that Shift

the Aggregate Demand Curve

1. Change in consumer spending

a. Consumer wealth

b. Consumer expectations

c. Household debt

d. Taxes

2. Change in investment spending

a. Interest rates

b. Expected returns

• Expected future business conditions

• Technology

• Degree of excess capacity

• Business taxes

3. Change in government spending

4. Change in net export spending

a. National income abroad

b. Exchange rates

mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 190mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 190 8/21/06 4:51:08 PM8/21/06 4:51:08 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 10

Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply

191

here to the “interest-rate effect” resulting from a change

in the price level. Instead, we are identifying a change in

the real interest rate resulting from, say, a change in

the nation’s money supply. An increase in the money sup-

ply lowers the interest rate, thereby increasing investment

and aggregate demand. A decrease in the money supply

raises the interest rate, reducing investment and decreas-

ing aggregate demand.

Expected Returns Higher expected returns on

investment projects will increase the demand for capital

goods and shift the aggregate demand curve to the right.

Alternatively, declines in expected returns will decrease in-

vestment and shift the curve to the left. Expected returns,

in turn, are influenced by several factors:

• Expectations about future business conditions If

firms are optimistic about future business conditions,

they are more likely to forecast high rates of return

on current investment and therefore may invest more

today. On the other hand, if they think the economy

will deteriorate in the future, they will forecast low

rates of return and perhaps will invest less today.

• Technology New and improved technologies

enhance expected returns on investment and thus

increase aggregate demand. For example, recent

advances in microbiology have motivated pharma-

ceutical companies to establish new labs and produc-

tion facilities.

• Degree of excess capacity A rise in excess capacity—

unused capital—will reduce the expected return on

new investment and hence decrease aggregate

demand. Other things equal, firms operating facto-

ries at well below capacity have little incentive to

build new factories. But when firms discover that

their excess capacity is dwindling or has completely

disappeared, their expected returns on new invest-

ment in factories and capital equipment rise. Thus,

they increase their investment spending, and the ag-

gregate demand curve shifts to the right.

• Business taxes An increase in business taxes will

reduce after-tax profits from capital investment and

lower expected returns. So investment and aggregate

demand will decline. A decrease in business taxes will

have the opposite effects.

The variability of interest rates and expected returns

makes investment highly volatile. In contrast to consump-

tion, investment spending rises and falls often, indepen-

dent of changes in total income. Investment, in fact, is the

least stable component of aggregate demand.

Government Spending

Government purchases are the third determinant of aggre-

gate demand. An increase in government purchases (for

example, more military equipment) will shift the aggregate

demand curve to the right, as long as tax collections and

interest rates do not change as a result. In contrast, a re-

duction in government spending (for example, fewer trans-

portation projects) will shift the curve to the left.

Net Export Spending

The final determinant of aggregate demand is net export

spending. Other things equal, higher U.S. exports mean

an increased foreign demand for U.S. goods. So a rise in

net exports (higher exports relative to imports) shifts the

aggregate demand curve to the right. In contrast, a de-

crease in U.S. net exports shifts the aggregate demand

curve leftward. (These changes in net exports are not

those prompted by a change in the U.S. price level—

those associated with the foreign purchases effect. The

changes here explain shifts of the curve, not movements

along the curve.)

What might cause net exports to change, other than

the price level? Two possibilities are changes in national

income abroad and changes in exchange rates.

National Income Abroad Rising national

income abroad encourages foreigners to buy more prod-

ucts, some of which are made in the United States. U.S.

net exports thus rise, and the U.S. aggregate demand curve

shifts to the right. Declines in national income abroad do

the opposite: They reduce U.S. net exports and shift the

U.S. aggregate demand curve to the left.

Exchange Rates Change in the dollar’s exchange

rate—the price of foreign currencies in terms of the U.S.

dollar—may affect U.S. exports and therefore aggregate de-

mand. Suppose the dollar depreciates in terms of the euro

(meaning the euro appreciates in terms of the dollar). The

new, relatively lower value of dollars and higher value of

euros enables European consumers to obtain more dollars

with each euro. From their perspective, U.S. goods are now

less expensive; it takes fewer euros to obtain them. So

European consumers buy more U.S. goods, and U.S. ex-

ports rise. But American consumers can now obtain fewer

euros for each dollar. Because they must pay more dollars to

buy European goods, Americans reduce their imports. U.S.

exports rise and U.S. imports fall. Conclusion: Dollar de-

preciation increases net exports (imports go down; exports

go up) and therefore increases aggregate demand.

mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 191mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 191 8/21/06 4:51:08 PM8/21/06 4:51:08 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART THREE

Macroeconomic Models and Fiscal Policy

192

Aggregate Supply

Aggregate supply is a schedule or curve showing the level

of real domestic output that firms will produce at each

price level. The production responses of firms to changes

in the price level differ in the long run , which in macroeco-

nomics is a period in which nominal wages (and other re-

source prices) match changes in the price level, and the

short run , a period in which nominal wages (and other

resource prices) do not respond to price-level changes. So

the long and short runs vary by degree of wage adjust-

ment, not by a set length of time such as 1 month, 1 year,

or 3 years.

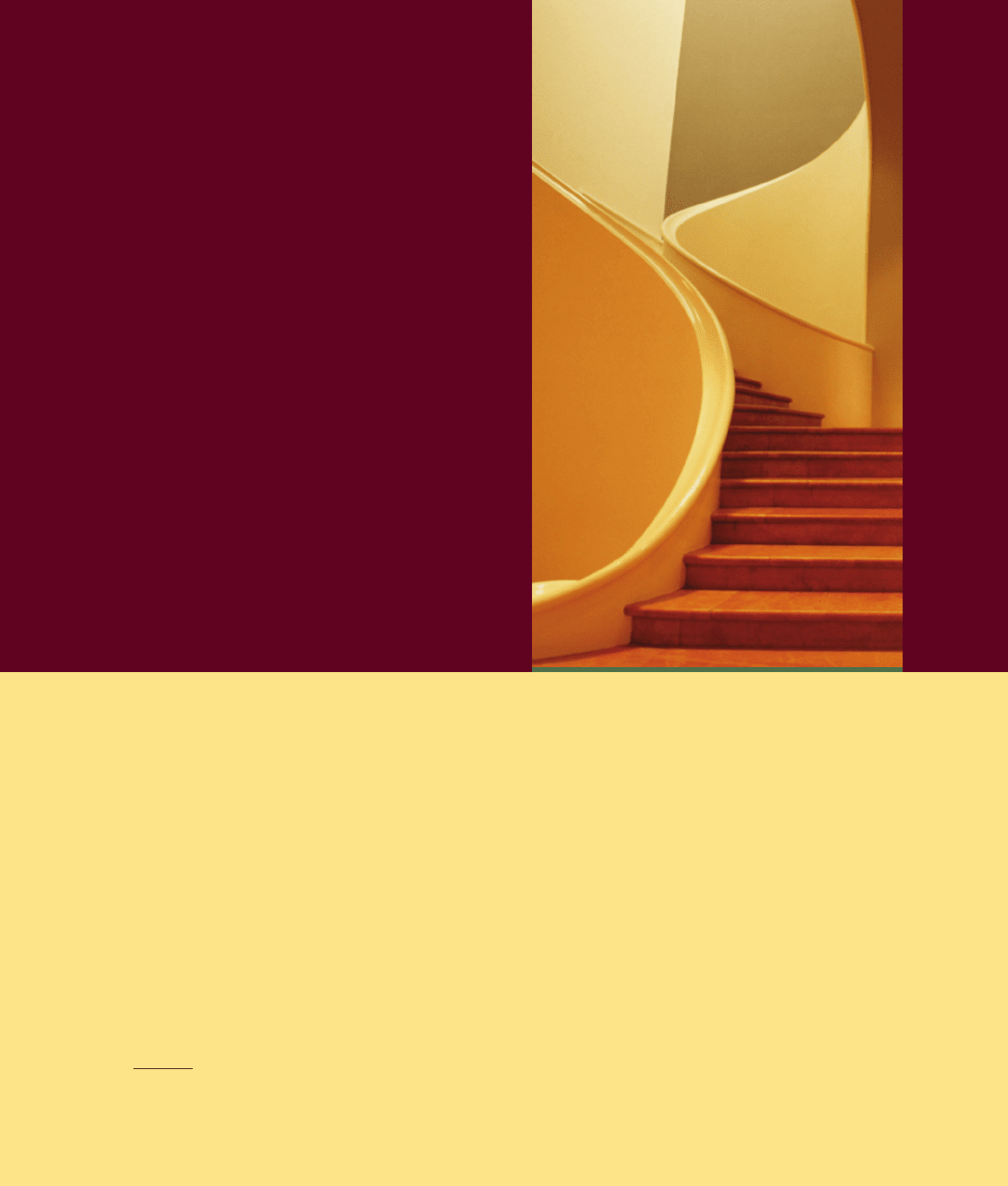

Aggregate Supply in the Long Run

In the long run, the aggregate supply curve is vertical at

the economy’s full-employment output (or its potential

output), as represented by AS

LR

in Figure 10.3 . When

changes in wages respond completely to changes in the

price level, those price-level changes do not alter the

amount of real GDP produced and offered for sale.

Consider a one-firm economy in which the firm’s

owners must receive a real profit of $20 in order to pro-

duce the full-employment output of 100 units. The real

reward the owner receives, not the level of prices, is what

really counts. Assume the owner’s only input (aside from

entrepreneurial talent) is 10 units of hired labor at $8

per worker, for a total wage cost of $80. Also, assume

that the 100 units of output sell for $1 per unit, so total

QUICK REVIEW 10.1

• Aggregate demand reflects an inverse relationship between

the price level and the amount of real output demanded.

• Changes in the price level create real-balances, interest-rate,

and foreign purchases effects that explain the downward

slope of the aggregate demand curve.

• Changes in one or more of the determinants of aggregate

demand (Figure 10.2) alter the amounts of real GDP

demanded at each price level; they shift the aggregate

demand curve. The multiplier effect magnifies initial

changes in spending into larger changes in aggregate

demand.

• An increase in aggregate demand is shown as a rightward

shift of the aggregate demand curve; a decrease, as a leftward

shift of the curve.

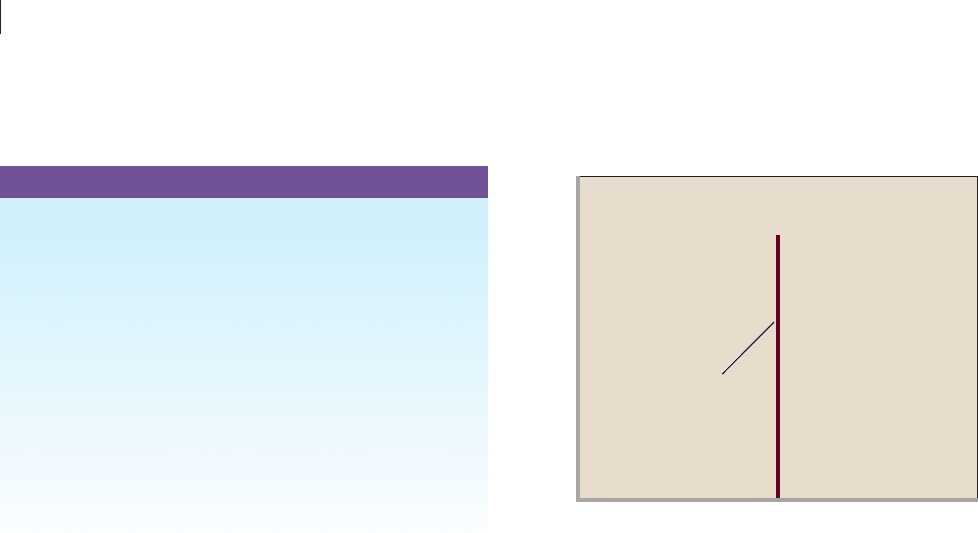

AS

LR

Long -run

aggregate

supply

0

Price level

Real domestic output, GDP

Q

f

FIGURE 10.3 Aggregate supply in the long run. The

long-run aggregate supply curve AS

LR

is vertical at the full-employment level

of real GDP (Q

f

) because in the long run wages and other input prices rise

and fall to match changes in the price level. So price-level changes do not

affect firms’ profits and thus they create no incentive for firms to alter their

output.

Dollar appreciation has the opposite effects: Net

exports fall (imports go up; exports go down) and aggregate

demand declines.

revenue is $100. The firm’s nominal profit is $20 (

$100 $80), and using the $1 price to designate the

base-price index of 100, its real profit is also $20 (

$20兾1.00). Well and good; the full-employment output

is produced.

Next, suppose the price level doubles. Would the

owner earn more than the $20 of real profit and therefore

boost production beyond the 100-unit full-employment

output? The answer is no, given the assumption that nom-

inal wages and the price level rise by the same amount, as

is true in the long run. Once the product price has doubled

to $2, total revenue will be $200 ( 100 $2). But the

cost of 10 units of labor will double from $80 to $160 be-

cause the wage rate rises from $8 to $16. Nominal profit

thus increases to $40 ( $200 $160). What about real

profit? By dividing the nominal profit of $40 by the

new price index of 200 (expressed as a decimal), we obtain

real profit of $20 ( $40兾2.00). Because real profit does

not change, the firm will not alter its production. Because

the firm’s output is the economy’s output, real GDP will

remain at its full-employment level.

In the long run, wages and other input prices rise or

fall to match changes in the price level. Changes in the

price level therefore do not change real profit, and there

is no change in real output. As shown in Figure 10.3 ,

the long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical at

the economy’s potential output (or full-employment

output).

mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 192mcc26632_ch10_187-207.indd 192 8/21/06 4:51:08 PM8/21/06 4:51:08 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES