Marshall L. Stoller, Maxwell V. Meng-Urinary Stone Disease

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 33 / Open Stone Surgery 639

639

From: Current Clinical Urology, Urinary Stone Disease:

A Practical Guide to Medical and Surgical Management

Edited by: M. L. Stoller and M. V. Meng © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

33

Open Stone Surgery

Elizabeth J. Anoia, MD and Martin I. Resnick, MD

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

INDICATIONS FOR OPEN STONE SURGERY

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

RESULTS

COMPLICATIONS

CONCLUSIONS

REFERENCES

Key Words: Nephrolithiasis; surgery; anatrophic nephrolithotomy;

open surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Urinary lithiasis is a disease process that predates the Hippocratic Oath (1). It afflicts

males three times more frequently than females with a peak age incidence occurring in

the twenties to forties. Most cases of stone disease are not linked to a specific genetic

defect and their development is related to multiple external factors, including diet. The

main types of stones are composed of calcium, struvite, uric acid, and cystine; the com-

position of each stone is unique owing to the variety of etiology and patient response to

the different therapies available (2). Medical, as well as surgical therapies, are both used

as effective forms of treatment. This chapter will focus specifically on the role of open

stone surgery in the treatment of patients with urinary lithiasis.

The surgical treatment of urolithiasis has undergone a rapid evolution over the past

25 yr. Before the introduction and refinement of extracorporeal, endourologic, and

percutaneous techniques, urinary stones required major open surgical procedures, which

had a significant morbidity and potential for renal loss. The advent of these newer less

invasive techniques has resulted in a shift in the manner in which all types of stones are

managed.

640 Anoia and Resnick

One open surgical treatment option is termed anatrophic nephrolithotomy. Anatrophic

nephrolithotomy is a procedure that has been used by urologists for over 30 yr for the

removal of staghorn renal calculi. The original description was by Smith and Boyce in

1968 and was based on the principle of placing the nephrotomy incision through a plane

of the kidney that is relatively avascular—between the anterior and posterior segmental

arteries. This approach avoids damage to the renal vasculature and subsequent atrophy

of the renal parenchyma, hence the term anatrophic (3).

Other types of open stone surgery include radial nephrotomies, pyelolithotomy,

extended pyelolithotomy, and ureterolithotomy. Pyelolithotomy refers to the incision

of the renal pelvis. Radial nephrotomy describes a procedure in which multiple paren-

chymal incisions are made over the calculus to effect its removal. A simple pyelolitho-

tomy can be used for partial staghorn stones or multiple 1–2 cm stones that extend into

the calyces. An extended pyelolithotomy, also referred to as the Gil-Vernet approach,

is indicated for more complex stones that extend into infundibula (4). Ureterolitho-

tomy can be performed throughout the entire length of the ureter when extracorporeal

shockwave lithotripsy (SWL) or endoscopic techniques fail. The surgical approach

depends on the location of the stone—at the ureteropelvic junction, in the proximal

half, or in the distal half.

INDICATIONS FOR OPEN STONE SURGERY

Struvite stones are often associated with urinary tract infections, and the coexistence

of these two conditions makes it difficult to eradicate either. Definitive treatment of these

stones is generally advocated because of the significant morbidity and mortality asso-

ciated with untreated infected calculi. Blandy and Singh found that patient survival is

reduced with untreated staghorn calculi, with a mortality rate of 28% at 10 yr (5). The

American Urologic Association Nephrolithiasis Clinical Guidelines Panel in 1994 rec-

ommends a percutaneous procedure with or without SWL as an initial treatment for

complex staghorn calculi (6). However, in specific situations anatrophic nephrolitho-

tomy remains the optimal treatment option for renal calculi and thus has maintained an

important, albeit smaller, role in the treatment of these large complex stones. Anatrophic

nephrolithotomy involves not only removal of the stone but also reconstruction of the

intrarenal collecting system to eliminate anatomic obstruction. Thus, this procedure

would improve urinary drainage, thereby reducing the likelihood of urinary tract infec-

tion, which would prevent recurrent stone formation.

The indications for all open stone surgeries have changed somewhat with advances

in minimally invasive methods of treating stones; however, the inability to successfully

eradicate a stone with less invasive methods remains an important indication. In 1994,

Assimos (7) outlined specific anatomic clinical scenarios for open renal or ureteral

surgery. Calyceal diverticular stones can be difficult to treat percutaneously when the

diverticula are intimately associated with the hilar vessels or have an extrarenal exten-

sion. Open surgical pyelolithotomy and pyeloplasty has been recommended in kidneys

with stones and a ureteropelvic junction obstruction if there is a large redundant pelvis

that necessitates tapering, a high ureteral insertion, a long segment of stricture, if the

obstruction is associated with an aberrant lower pole artery, and in patients with solitary

kidneys. Patients with other forms of nephroureteral obstruction which require stone

treatment in conjunction with anatomic correction are often better served with an open

definitive procedure.

Chapter 33 / Open Stone Surgery 641

Ureteral stones associated with ureterocele, ectopic ureters, obstructing congenital

megaureter, or kidney with severe infundibular stenosis are examples that could be

treated with a ureterolithotomy (7). Stones in the presence of an ileal conduit present a

treatment challenge, especially if there is a Wallace ureterointestinal anastomosis (8).

Overall, less than 3% of all upper ureteral stones will require an open procedure. Char-

acteristics more common to this group are moderate to severe hydronephrosis and larger

stone size (9).

Emphysematous pyelonephritis associated with stones that have been unsuccessfully

treated percutaneously is another indication for an open approach. Ectopic kidneys or

pelvic horseshoe kidneys may require an open surgery if the major stone burden is in

extremely anterior pelvis that limits adequate shockwave focusing or percutaneous

access. A preoperative abdominal angiogram is recommended as the blood supply can

vary (7).

Certain stone compositions (calcium oxalate monohydrate and brushite) may not be

as effectively treated with SWL therapy, and open procedures may be required if they

are refractory after multiple attempts. Impacted stones may also require an open salvage

procedure (2,7,9).

Anatrophic nephrolithotomy or other open procedures can also be the first line treat-

ment in patients requiring stone removal but have a body habitus that makes the less

invasive procedures difficult to impossible (7,10). The presence of limb contractures,

stones in a transplant kidney (11), and obesity often present challenges for positioning

and access. These include an inability to reach stones with traditional instruments, the

risk of severe tissue necrosis secondary to positioning, and technical issues. SWL can

only be performed in patients in whom the stone–skin distance equals the approximate

focal length of the specific machine. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) also requires

adequate fluoroscopic penetration to visualize the stone.

Despite the need for open surgery, these procedures come with their own set of risks.

There can be difficulty in identifying anatomic landmarks and inadvertent incisions have

been made above the 10th rib. Other problems are awkward positions for the surgeons,

well-vascularized subcutaneous tissue leading to excessive bleeding from skin inci-

sions, intraoperative rhabdomyolysis resulting in temporary renal failure, and wound

infection (10).

Other relative indications include select cases of complex stone disease, previous

renal surgery, comorbid disease, and patient preference (12,13). Before deciding on a

treatment strategy, the above factors, the urologist’s preference and access to equipment,

and the patient’s individual situation must be considered.

If a patient’s clinical presentation does not mandate open surgery, other important

variables in deciding between open procedures and other less invasive modalities must

be considered. Each option has its own advantages, disadvantages, and different stone

free rate. Studies have compared the cost and morbidity of percutaneous vs open flank

procedures. Percutaneous procedures involved less anesthesia time, less duration of

hospitalization, less recuperative time, decreased transfusion requirements, less post-

operative need for narcotics, and less total cost without an increased risk for renal

parenchymal damage (14,15). However this may not be the case when unsuccessful

percutaneous procedures are considered, demonstrating the importance of the learning

curve and the stone burden (15). Larger stones require more manipulation, longer pro-

cedures, and often multistage approaches.

642 Anoia and Resnick

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Incisions

There are several approaches for open stone surgery, depending on the location of the

stone and patient and physician preferences previously described: the commonly used

flank approach, the posterior approach, and the most invasive transperitoneal approach.

The basic surgical principles of stone extraction are similar; the difference lies in how

access to the kidney and ureter is obtained. The flank approach may be subcostal or

intercostal; this approach provides better access to the renal hilum and the upper pole

(16). The posterior approach is an excellent procedure for pyelolithotomy and upper

third ureterolithotomy with decreased postoperative pain and shorter hospital stay (17).

The transabdominal approach is reserved for patients that are difficult to position or for

patients who have undergone multiple previous surgical procedures (16). In any case

after the administration of appropriate preoperative intravenous antibiotics and induc-

tion of general anesthesia, a Foley catheter is placed in the bladder.

For the flank approach the patient is placed in the standard flank position with eleva-

tion of the kidney rest and flexion of the operating table to achieve adequate spacing

between the lower costal margin and the iliac crest. Three-inch-wide adhesive tape

applied at the shoulders and hips is often used to secure the patient to the table. Adequate

padding should be used to protect pressure points. The incision can be placed through

the bed of either the 11th or 12th rib, depending on the estimated position of the kidney

and the location of the stone, and can be extended as far medially as the lateral border

of the rectus sheath. If a previous flank incision has been made for renal surgery, it is

preferable to place the incision above the old scar, ensuring that access to the kidney can

be achieved through unscarred tissue. After rib identification and resection when access

has been gained into the retroperitoneal space, Gerota’s fascia is visualized overlying the

kidney (16).

The technique for the posterior approach is as follows. The patient is placed in the

lateral position with the table flexed to extend the lumbar region. A vertical lumbar

incision along the lateral margin of the sacrospinalis muscle is made starting superiorly

at the upper margin of the 12th rib extending laterally to the iliac crest inferiorly. The

incision is carried down through the lumdodorsal fascia to the sacrospinalis and quadra-

tus lumborum muscles. These are then medially retracted to approach the renal fossa,

avoiding the morbidity of a muscle-splitting incision. If greater superior exposure is

needed, the 12th rib can be resected or the costovertebral attachment of this rib severed.

A selfretaining retractor is then inserted, being careful to avoid injury to the pleura and

subcostal vessels. After Gerota’s fascia is incised, excellent exposure is gained to the

renal pelvis and upper ureter for simple or extended pyelolithotomy or ureterolitho-

tomy (17).

Anatrophic Nephrolithotomy

In the classic description of anatrophic nephrolithotomy (3) Gerota’s fascia is incised

in a cephalad–caudal direction, which facilitates returning the kidney to its fatty pouch

at the end of the operation. The kidney is fully mobilized and the perinephric fat is

carefully dissected off the renal capsule with care taken not to disrupt the capsule. Should

the capsule become inadvertently incised, it can be closed at that time with fine chromic

catgut sutures. The kidney is now free to be suspended in the operative field by utilizing

Chapter 33 / Open Stone Surgery 643

a broad umbilical tape at each pole. At this point a preliminary portable plain radiograph

is obtained to identify the position and size of the stone(s).

For the renal hilar dissection, the main renal artery and the posterior segmental branch

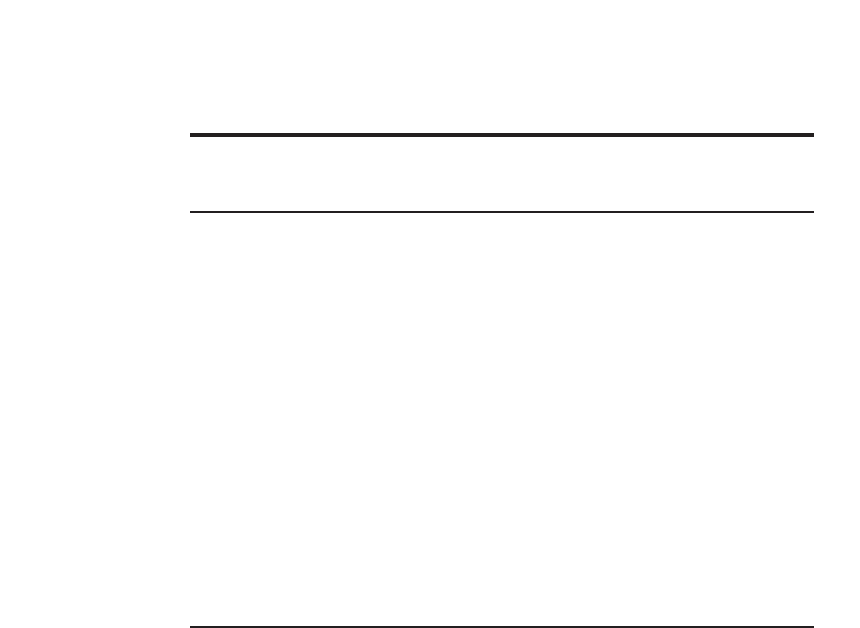

are approached posteriorly, carefully identified, and dissected (Fig. 1A). The renal pel-

vis and ureter should be identified, but not dissected. The avascular plane is identified

by temporarily clamping the posterior segmental artery and injecting 20 mL of methy-

lene blue intravenously. This results in the blanching of the posterior renal segment

while the anterior portion turns blue, allowing identification and marking of the avascu-

lar plane (Fig. 1B) (18). Placing the nephrotomy incision through this plane will achieve

maximal renal parenchymal preservation and minimize blood loss. The avascular plane

can also be identified with the use of a Doppler to localize the area of the kidney with

minimal blood flow.

More extensive renal hilar dissection can be avoided by utilizing a modification of the

original procedure described by Smith and Boyce. Redman and associates relied on the

relatively constant segmental renal vascular supply in the identification of Brodel’s line.

They advocated placing the incision at the expected location of the avascular plane after

clamping the renal pedicle with a Satinsky clamp, in an effort to prevent vasospasm of

the renal artery and warm ischemia (19). This modification can be time-saving and spare

extensive dissection of the renal hilum.

More recently, McAninch et al. have added another modification to this classic descrip-

tion in an attempt to maximally preserve renal function. In their description the renal

capsule is incised over the lateral convex surface of the kidney and a parenchymal

incision is made 1–2 cm posterior to the capsulotomy. This location approximates the

“avascular plane” and allows access to the collecting system directly over the stone

burden. The two potential advantages are avoiding overlying suture lines and ready

access to the collecting system (20).

Just before occluding the renal artery, 25 g of intravenous mannitol is administered.

This promotes a postischemic diuresis and prevents the formation of intratubular ice

Fig. 1. Anatrophic nephrolithotomy. (A) Main renal artery and branches are isolated. (B) The

posterior segmental artery is occluded, and methylene blue is administered intravenously. The

resulting demarcation between pale ischemic and bluish perfused parenchyma defines a rela-

tively avascular nephrotomy plane.

644 Anoia and Resnick

crystals by increasing the osmolarity of the glomerular filtrate. The main renal artery is

occluded with an atraumatic bulldog vascular clamp. A bowel bag is quickly placed

around the kidney, and it is insulated from the body wall and peritoneal contents with dry

packs. Hypothermia is then initiated with iced saline slush covering the kidney. The

kidney should be cooled for 10–15 min before the nephrotomy incision is made. This

should allow achievement of a core renal temperature of 15–20°C, which will allow safe

ischemic times from 60 to 75 min and minimizes renal parenchymal damage (21). The

ice slush should be continuously reapplied as needed throughout the procedure.

The renal capsule is incised sharply over the previously identified line, being careful

to avoid extension into the upper and lower poles. The renal parenchyma is bluntly

dissected with the back of the scalpel handle which minimizes injury to the intrarenal

arteries that are traversed. Small bleeding vessels can be controlled with 4-0 or 5-0

chromic catgut figure-eight suture ligature. If renal back bleeding continues to be a

problem despite these measures, the main renal vein can be occluded.

As the nephrotomy incision proceeds toward the renal hilum, the ideal location to

enter the collecting system is at the base of the posterior infundibula. The intraoperative

radiograph can be used as a guide to the pelvis and the base of the calyx. Occasionally,

with large posterior calyceal calculi, a dilated posterior calyx will be entered initially.

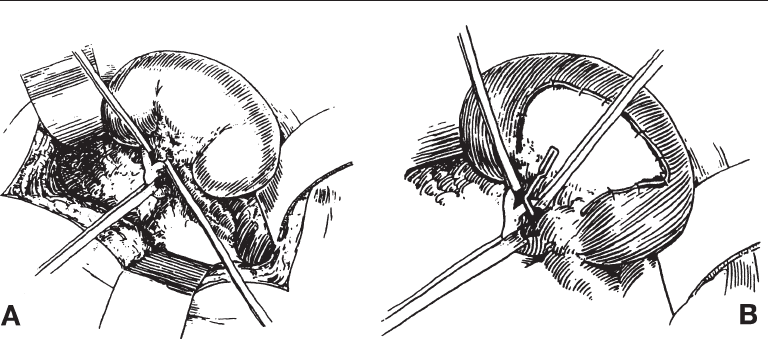

The remainder of the collecting system is identified with a probe and opened. If a

posterior infundibulum is entered first, the incision is then carried toward the renal

pelvis (Fig. 2). The stone is visualized and all ramifications of the stone are exposed by

opening adjacent infundibula into the calyces. In order to minimize stone fragmentation

and retained calculi, the stone should not be manipulated or removed until all of the

calyceal and infundibular extensions are appropriately identified and incised. This

allows for complete visualization and mobilization of the collecting system and calculi.

Ideally, the stone or stones should be removed without fragmentation; however, often

it is inevitable that there will be some piecemeal extraction. If this is necessary, a

ureteral stent can be inserted to prevent stone migration down the ureter during manipu-

lation. Each calyx should usually be inspected for stone fragments. After removal of all

stone fragments, the renal pelvis and calyces are copiously irrigated with cold saline and

the irrigant is aspirated. A nephroscope can be used to look for residual fragments. A

Fig. 2. The collecting system is carefully incised.

Chapter 33 / Open Stone Surgery 645

plain radiograph or ultrasonography are also options. At this time, a “double-J” ureteral

stent is passed from the renal pelvis into the bladder if this was not done at the time of

stone manipulation. The routine use of internal ureteral catheters is encouraged. They

provide good urinary drainage, protect the freshly reconstructed collecting system, and

minimize postoperative urinary extravasation.

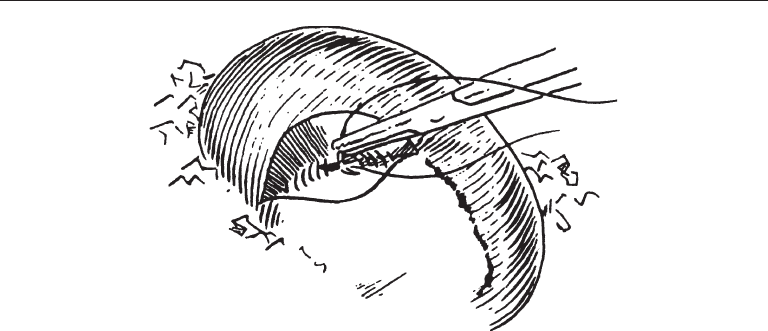

The next step in the procedure is the reconstruction of the intrarenal collecting system

with correction of coexistent anatomic abnormalities that may be present. Infundibular

stenosis or stricture, which results in obstruction promoting urinary stasis and recurrent

stone formation, should be corrected with caliorrhaphy or calicoplasty. All intrarenal

reconstructive suturing is accomplished with 5-0 or 6-0 chromic catgut sutures. When

suturing the mucosal edges, it is important to avoid incorporation of underlying inter-

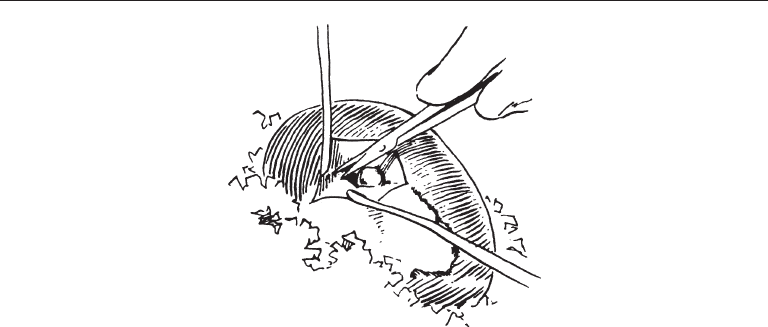

lobular arteries, thus preventing ischemia. The renal pelvis is then closed, first with

reinforcing corner sutures and then with a running 6-0 chromic catgut suture (Fig. 3).

Before closing the renal capsule bleeding points are identified and ligated with 4-0 or 5-

0 chromic figure-eight sutures. The renal capsule is closed with a running lock stitch of

4-0 chromic catgut suture or mattress sutures over bolsters can be used.

McAninch et al. have also created a modification involving renal reconstruction after

nephrolithotomy. Traditionally, the infundibula are reconstructed and the collecting

system is formally closed. The modification simplifies this closure by not reconstruct-

ing the infundibula; instead, the capsular and parenchymal staggered incisions are

closed with nonoverlapping suture lines forming a watertight renal closure. When

postoperative renal function results are compared there is a slight decrease in renal

function in McAninch’s series; however, overall findings are comparable to Smith and

Boyce (20).

After the capsule is closed and adequate hemostasis has been achieved, the renal

artery is unclamped and the kidney is observed for good hemostasis and return of pink

color and turgor. It is then returned into Gerota’s fascia, and the kidney and proximal

ureter are covered with some perirenal fat to minimize postoperative scar formation. If

Gerota’s fascia is unavailable because of previous surgery, omentum can be mobilized

through a peritoneal opening and wrapped around these structures. The peritoneal open-

ing should be sutured to the omentum to prevent herniation of the abdominal viscera.

Fig. 3. The renal pelvis is closed with a running 6-0 chromic suture.

646 Anoia and Resnick

A Penrose or suction-type drain is placed within Gerota’s fascia and brought out

through a separate stab incision. This drain is left in place until minimal drainage occurs,

usually by the third or fourth postoperative day. Nephrostomy tubes are generally avoided

because of their potential for causing infection or further renal damage. The flank mus-

culature and skin are closed in the standard fashion.

Pyelolithotomy

A pyelolithotomy also begins with mobilization of the kidney after Gerota’s fascia is

incised. The degree of mobilization is dependent on the size of the stone. If a smaller,

more centrally located renal pelvis stone is anticipated, it is not necessary to dissect the

renal artery. The renal pelvis and upper ureter are identified and the pelvis is approached

posteriorly to avoid injury to the renal vein. Two stay sutures are placed in the renal

pelvis using 4-0 chromic suture and a longitudinal incision made. Care must be taken to

avoid extension into the ureteropelvic junction so as to reduce the risk of subsequent

scarring and the development of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. After the successful

removal of all stones, the renal pelvis is closed with a 4-0 chromic continuous suture.

Drainage of the system is performed as described previously (16).

Extended Pyelolithotomy

In an extended pyelolithotomy described by Gil-Vernet (4), the dissection is more

extensive. The thin layer of connective tissue that extends from the renal capsule onto

the renal pelvis must be carefully incised in order to gain access to the renal hilum and

infundibula. The dissection is carried subparenchymally to expose the renal pelvis and

the infundibula. A curvilinear pyelotomy incision is made over the stone and then

extended to the superior and inferior calyces. The stone is freed from the mucosa and

removed. Once one is confident that all fragments have been removed with the aid of

radiographs and nephroscopy, the collecting system is closed with a continuous 4-0

chromic catgut suture as described above. The infundibular incisions will be covered by

the renal parenchyma; therefore it is not necessary to completely close them (22).

Drainage of the flank is again performed.

Ureterolithotomy

Ureterolithotomy can be performed via multiple approaches. The flank or posterior

lumbotomy incision can be used for the upper ureter, an anterior extraperitoneal muscle-

splitting incision can adequately expose the mid-ureter, and the lower ureter can be

accessed via a Gibson, Pfannenstiel, or midline suprapubic incision (8). Once the

approach is decided, radiographs are obtained to confirm stone position. For an upper

ureterolithotomy Gerota’s fascia is opened and the upper ureter is identified. A Babcock

forceps or vessel loop is placed on the ureter above the stone for traction and to prevent

stone migration. Dissection is carried downward to provide adequate exposure, being

careful not to devascularize the ureter or injure the muscularis layer. A vertical uretero-

tomy is made over the stone without injuring the posterior ureteral wall. After careful

stone extraction the entire ureter is irrigated and a double J stent may be placed. The

incision is closed longitudinally with simple interrupted 5-0 sutures placed 1–2 mm

apart. A Penrose or suction drain is used to drain the area of the ureterotomy. The

principles of stone extraction remain the same in a distal ureterolithotomy; however,

exposure of the ureter requires certain other maneuvers. Identifying the iliac vessels

Chapter 33 / Open Stone Surgery 647

and dividing the obliterated umbilical vessels can help. The bladder is reflected medi-

ally and kept decompressed with a Foley catheter (8,23).

Postoperative Management

Postoperative management after anatrophic nephrolithotomy, pyelolithotomy, or ure-

terolithotomy should follow the same principles that guide management after other

major operations. Intravenous fluids are maintained to achieve brisk urine output and

until the patient is able to tolerate a clear liquid diet. Broad-spectrum intravenous anti-

biotics are administered perioperatively and continued postoperatively for 5–7 d. Anti-

biotic coverage is guided by preoperative urine culture and sensitivity findings. The

ureteral stent is removed cystoscopically at approx 7 d postoperatively in uncomplicated

cases. A urine culture is checked for persistence of infection. At 1–2 mo a follow-up

intravenous pyelogram is obtained.

RESULTS

Stone free rates with staghorn calculi show that 21% of percutaneous procedures

required additional procedures to clear the stone burden. In contrast only 4% of patients

required further intervention after anatrophic nephrolithotomy. Residual stone disease

leading to multiple procedures is one of the significant drawbacks of PCNL (14). Less

than 10 yr after its development SWL monotherapy was found to have a 61% stone-free

rate at 8 mo of follow-up (24). PCNL or PCNL–SWL sandwich therapy stone free rates

were reported as 54–95% depending on stone volume and collecting system dilatation

(7). Endoscopic therapy of renal and ureteral stones with the Holmium:YAG laser is

reported to have an overall stone free rate of 95% when combined with other types of

lithotripsy (25). Overall, anatrophic nephrolithotomy stone free rates range from 80–

100% depending on collecting system dilatation and stone burden (12,26).

Open pyelolithotomy has a stone-free rate that approaches 100% if there is a single

stone. However if a staghorn stone is present or if there are multiple calyceal stones, the

stone-free rate decreases to approx 90% (16). A retrospective study by Paik et al. in 1998

reported an initial stone free rate of 93% in patients with large renal pelvic stones

undergoing simple or extended pyelolithotomy (13).

In 1997, the American Urologic Association published a meta-analysis on the cur-

rently available methods for treating ureteral calculi. Stone free rates for ureterolitho-

tomy vary from 84–100% depending on stone size and location (9,27). SWL had a 57%

stone-free rate with one-third of patients requiring second procedures. Endoscopic pro-

cedures were more successful with an initial stone-free rate of 74% and a final clearance

rate of 95% after additional procedures (9). Overall, the goals of open stone surgery

should be to remove all calculi and fragments, to improve urinary drainage of any

obstructed intrarenal collecting system, to eradicate infection, to preserve and improve

renal function, and to prevent stone recurrence (28).

As open stone surgery accounts for <5% of treatment modalities for staghorn and

other complex stones, there are now other less invasive techniques either alone or in

combination that have replaced these procedures. Despite impressive advances with the

less invasive techniques, anatrophic nephrolithotomy, pyelolithotomy, or ureterolitho-

tomy remain viable treatment options for large or staghorn calculi not expected to be

eliminated with a reasonable number of less invasive procedures. Staghorn stones asso-

ciated with anatomic abnormalities also require open surgical correction.

648 Anoia and Resnick

COMPLICATIONS

Complications resulting from open stone surgery are similar to other forms of open

surgery, for example wound infections and postoperative fevers. Pulmonary compli-

cations are common including atelectasis, pneumothorax, and pulmonary embolism.

Patients with a history of pulmonary disease should likely undergo preoperative evalu-

ation with pulmonary function testing and initiation of vigorous pulmonary toilet

before surgery. Postoperatively, patients should be encouraged to breathe deeply, and

use of an incentive spirometer should be routine to prevent atelectasis. Early ambulation

will also be beneficial.

Pneumothorax should occur in fewer than 5% of patients (28). A patient with a history

of pyelonephritis or previous renal surgery is at increased risk. Inadvertent opening of

the pleura, usually during incision and resection of a rib, should be identified and

repaired intraoperatively with a running chromic catgut suture. The lung is hyperinflated

just before the final suture is placed to ensure re-expansion of the lung. Chest tubes are

not routinely used but may be necessary if any question remains regarding the reliability

of the pleural closure. A chest radiograph should be obtained in the recovery room for

any patient who undergoes repair of a pleural defect. Pulmonary embolism remains a

potential complication of any major surgery. Routine use of support hose and sequen-

tial-compression stockings can lower the risk of deep venous thrombosis. Encourage-

ment of early ambulation is also an important preventive measure.

Significant postoperative renal hemorrhage after anatrophic nephrolithotomy should

occur in fewer than 10% of patients. Assimos and associates reported an incidence of

6.4%. Bleeding usually occurs immediately or approx 1 wk postoperatively. Extensive

intrarenal reconstruction, older age, impaired renal function, and presence of blood dys-

crasias were found to be significant risk factors. Slow bleeding will usually resolve on

its own; management includes correction of any bleeding abnormalities and replacement

with blood products as necessary. Oral aminocaproic acid can be successful in certain

cases. Bleeding that is brisk or cannot be adequately treated conservatively will require

a more aggressive approach. A renal arteriogram can help identify the lesion, and an

attempt at arteriographic embolization should be considered. Re-exploration may be

required in the remainder of the cases, with reinstitution of hypothermia and suture

ligation of the bleeding vessel(s). Persistent hematuria 1–4 wk postoperatively should

alert the clinician to the possibility of renal arteriovenous fistula formation or a false

aneurysm (29). Other possible complications that can result from arterial clamping

include renal injury and hypertension.

Urinary extravasation with any procedure should occur infrequently with the routine

use of perinephric drains and ureteral catheter drainage. Should drainage recur or persist

following removal of the drain and/or ureteral stent, replacement of the ureteral stent

should be considered to decompress the system and relieve any obstruction. Flank

abscess as a result of extravasation is an unusual complication that can usually be

managed conservatively with percutaneous drainage or may require open drainage (15).

Open ureterolithotomy has a complication rate ranging from 17–34% via the posterior

lumbotomy and flank approaches, respectively (9). A few complications that are unique

to this procedure include loss of the stone intraoperatively, fistulas, and strictures (8).

Preoperative localization and immobilization of the stone can decrease the risk of stone

loss. Fistulas, although uncommon, can occur with ureteral damage or infection. In 1993

a ureterofallopian fistula, manifesting as complete urinary incontinence, occurred after