Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The Byzantine empire, 1118–1204 641

If Andronikos, once in power, had kept his election promises and formed

a genuinely inclusive regency government for Alexios II, it is possible that he

might have held the Comnenian nobility together. His programme of admin-

istrative reform, admirable in itself, could have won him support even among

his peers if he had treated them fairly and generously. But by instituting a reign

of terror against all potential rivals for the regency, including the emperor’s

sister and mother, he provoked a serious revolt in Asia Minor; then, by go-

ing on to eliminate Alexios II and settle the succession on his son John, he

removed the only focus of consensus among the Comnenian kin-group, and

committed himself to dependence on a faction bound to him by self-interest.

The terror continued, and those who could escaped it by fleeing abroad, to

the courts of rulers who had had ties or treaties with Manuel and Alexios II.

Thus the sultan, the prince and patriarch of Antioch, the king of Jerusalem, the

pope, Frederick Barbarossa, the marquis of Montferrat, the king of Hungary

and, above all, the king of Sicily were approached by refugees imploring their

intervention. It was at the insistence of Manuel’s great-nephew, the pinkernes

Alexios Komnenos, that William II of Sicily sent the invasion force which took

Durazzo and Thessalonica in 1185. The stated aim of the expedition was to re-

place Andronikos with a young man claiming to be Alexios II: Pseudo-Alexioi

were the inconvenient but inevitable consequence – for later emperors as well –

of the fact that Andronikos had sunk Alexios’s body in the Bosphorus. The

Sicilian invasion thus not only recalled the past invasions of Rober Guiscard,

Bohemond and Roger II; it also set a precedent for the diversion of the Fourth

Crusade, both by the damage and humiliation it caused, and in the way

it involved the external ‘family of kings’ in the politics of the Comnenian

family.

Andronikos would probably have succeeded eventually in repelling the

Sicilian invasion, as he succeeded in quelling every organized conspiracy against

him, but the very diligence of his agents in hunting down potential conspira-

tors led, quite unpredictably, to the spontaneous uprising which toppled him.

When his chief agent went to arrest a suspect who had given no cause for

suspicion, the suspect slew the agent in desperation, and then did the only

thing he could do in order to avoid immediate capital punishment: he rushed

for asylum to the church of St Sophia. A crowd gathered, Andronikos – evi-

dently feeling secure – was out of town and, St Sophia being also the imperial

coronation church, one thing led to another. So Isaac Angelos became emperor

because he was in the right place at the right time, and this had a decisive effect

on the course of his reign. His propagandists claimed, and he firmly believed,

that his accession was providential, that he was the Angel of the Lord sent by

heaven to end the tyranny, so that his whole reign was ordained, blessed and

protected by God. He considered his power irreproachable and untouchable,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

642 paul magdalino

and he exercised it with a mixture of grandiosity and complacency which

was quite inappropriate to the situation. For other important people did not

share his belief. His miraculous elevation was not enough to convince Isaac

Komnenos in Cyprus, Peter and Asan in Bulgaria, Theodore Mangaphas in

Philadelphia and Basil Chotzas at Tarsia, near Nicomedia, that they owed loy-

alty to Constantinople, or to prevent two young men from raising rebellions

by pretending to be Alexios II. Among his own close family, it did not make up

for his lack of seniority, or his military incompetence: he was challenged by his

uncle John and his nephew Constantine. The Comnenian nobility as a whole

were not impressed, because many of them had equally good, if not better,

dynastic claims in terms of the hierarchy of kinship which had operated under

Manuel: Isaac was descended from Alexios I’s youngest daughter, but others

could trace their descent through the male line, and some could count John II

among their ancestors. For several of them, Isaac’s success was only an incentive

to follow it and turn up at St Sophia in the hope of being acclaimed. The first

to try this was Alexios Branas, the general who had halted the Sicilian invasion.

Having failed in this first attempt, he waited until he was put in command of

the army sent to quell the Vlakh revolt. What made his rebellion so dangerous

was the fact that he combined good Comnenian lineage with military expertise

and strong family connections among the military aristocracy of Adrianople.

Isaac was saved only by the loyalty of the people of Constantinople and a bold

sortie by Conrad of Montferrat.

During ten years in power, Isaac II faced at least seventeen revolts, a number

exceeded in the eleventh and twelfth centuries only by the twenty-one plots

that are recorded for the thirty-nine-year reign of Alexios I. Isaac undoubtedly

saw something providential in the fact of his survival, but repeated opposition

took its toll on the effectiveness of his rule, by making it virtually impossible for

him to delegate important military commands to highly competent noble com-

manders. This was probably decisive for the outcome of the rebellion of Peter

and Asan. Lack of support among the Comnenian nobility may have prompted

what was seen to be Isaac’s excessive favouritism to his chief bureaucrat, his

non-Comnenian maternal uncle Theodore Kastamonites, and to the latter’s

successor in office, Constantine Mesopotamites. It certainly drove the mem-

bers of five leading Comnenian families, Palaiologos, Branas, Kantakouzenos,

Raoul and Petraliphas, to mount the coup in 1195 which replaced Isaac with

his elder brother Alexios III.

Sibling rivalry had, as we have seen, threatened to destroy the Comnenian

system in the past, but it had been kept under control, and its eruption into

successful usurpation sealed the fate of the system in its twelfth-century phase.

Choniates saw the overthrow of brother by brother as the supreme manifes-

tation of the moral depravity for which the fall of Constantinople was just

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Byzantine empire, 1118–1204 643

retribution.

9

From the deposition of Isaac II proceeded the escape of his son

Alexios to the west just when the Fourth Crusade needed an excuse for a detour

via Constantinople. In their comeback, the internal and external dimensions of

the system fatally converged. Choniates, perhaps looking back to Andronikos

and even to his father, saw a pattern:

If anything was the supreme cause that the Roman power collapsed to its knees and

suffered the seizure of lands and cities, and, finally, itself underwent annihilation, this

was the members of the Komnenoi who revolted and usurped power. For, dwelling

among the nations which were unfriendly to the Romans, they were the bane of their

country, even though when they stayed at home they were ineffectual, useless and

incompetent in anything they tried to undertake.

10

This retribution apart, however, Alexios III faced relatively little opposition

from the Komnenoi. In 1200–1 there were provincial revolts led by his cousins

Michael Angelos and Manuel Kamytzes, and a one-day occupation of the Great

Palace in Constantinople by a son of Alexios Axouch, John Komnenos the Fat.

But otherwise, Alexios had fairly good support in the bureaucracy and the

church through his connection by marriage into the Kamateros family, and

the consortium of Comnenian families which brought him to power appear to

have been satisfied with his laissez-faire regime, and with his adoption of the

name Komnenos in preference to Angelos. All five families flourished after 1204;

four were to be prominent after 1261 in the restored empire of the Palaiologoi,

and the Palaiologoi gained a head start in their future ascendancy from the

marriage which Alexios III arranged between his daughter Eirene and Alexios

Palaiologos.

The marriage of another daughter, Anna, to Theodore Laskaris laid the

dynastic basis for the empire of Nicaea, the most successful of the three main

Greek successor states after 1204. Cousins of Isaac II and Alexios III established

the western state which enjoyed brief glory as the empire of Thessalonica and

then survived in north-western Greece as the despotate of Epiros. The empire

of Trebizond, which lasted until 1461, was ruled by a dynasty calling themselves

the Grand Komnenoi, who were descended from Andronikos I.

Under the successors of Manuel I, the Comnenian system, centred on Con-

stantinople, was programmed for self-destruction. Relocated to the provinces

after 1204 through the leading families of the last twelfth-century regimes,

it ensured the survival of the Byzantine empire for another two and a half

centuries, while losing none of its divisive potential.

9

Ibid., pp. 453–4, 532.

10

Ibid., p. 529.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

chapter 21

THE LATIN EAST, 1098– 1205

Hans Eberhard Mayer

the First Crusade ended with the conquest of Jerusalem on 15 July 1099,re-

sulting in the foundation of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem. This was to

become the biggest and most important crusader state but others had been

established while the crusade was en route.Fromthe autumn of 1097 to March

1098 Baldwin of Boulogne occupied the country west and east of the Eu-

phrates, finally taking over Edessa where he set up the county of Edessa which

protected the other crusader states in the north-east. Latin rule was imposed

on a predominantly Armenian population. Following the conquest of Antioch

in June 1098 Bohemond I of Taranto who had been the leading figure in the

long and bitter siege of the town succeeded in having his claim to Antioch

recognized by the leaders of the crusading army before the crusade started to

move again. Provenc¸al attempts to curb Norman ambitions had been thwarted.

Neither Baldwin nor Bohemond participated in the rest of the crusade and

neither one of them adhered to a promise made earlier to the Byzantine em-

peror that all conquests of formerly Byzantine territories would be restored to

Byzantium. Bohemond now established the principality of Antioch where a

distinctly Norman ruling class governed a population partly Muslim, partly

Greek. He gained legitimacy when he was invested with the principality by the

patriarch of Jerusalem on Christmas 1099.

When the crusaders had reached Ramla, the old capital of Palestine, they

appointed a Latin bishop there without any participation of the Greek church.

In retrospect this was to become the starting-point of a Latin church in Pales-

tine. After a siege of nearly six weeks Jerusalem was stormed and its population

massacred in a blood bath. On 12 August this success was consolidated when an

Egyptian army was beaten near Ascalon. Three years had passed since Godfrey

of Bouillon had set out from Lorraine. Organizing the success was more dif-

ficult. After Raymond of Toulouse had rejected a half-hearted offer to rule

over Jerusalem, Godfrey of Bouillon, duke of Lower Lorraine, was brought to

power by the army but refused the kingship and continued under the title of

644

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Latin east, 1098–1205 645

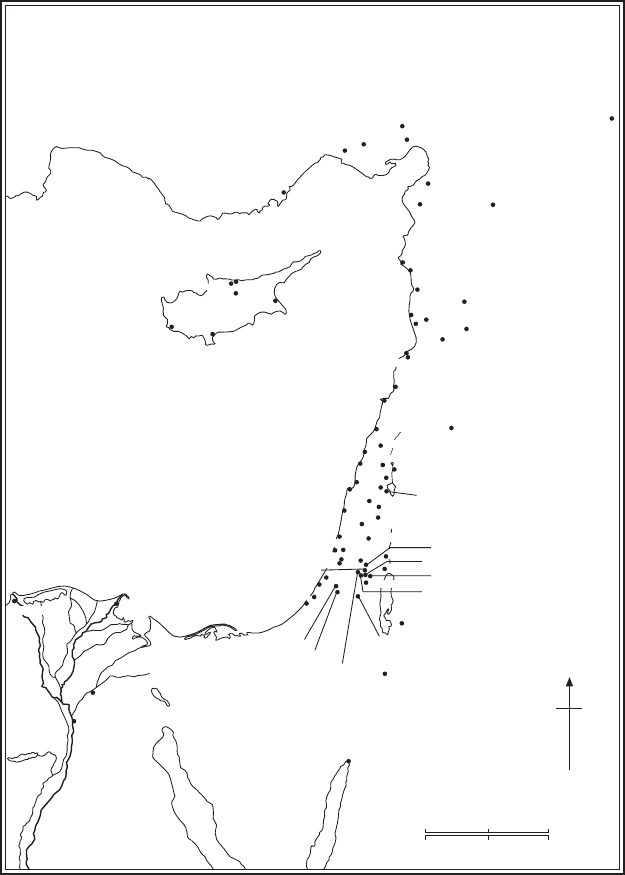

080160 km

050

100 miles

N

CILICIA

SELJUQS OF

RUM

COUNTY

OF

EDESSA

MEDITERRANEAN

SEA

DEAD SEA

SEA OF GALILEE

K

IN

G

D

O

M

O

F

J

E

R

U

S

A

L

E

M

P

R

I

N

C

I

P

A

L

I

T

Y

O

F

A

N

T

I

O

C

H

C

O

U

N

T

Y

O

F

T

R

I

P

O

L

I

ARMENIANS

Silifke

Tar sus

Adana

Sis

Anavarza

Edessa

Baghras

Antioch

Aleppo

Latakia

Jabala

Margat

Hamah

–

Belmont Abbey

Tripoli

Kyrenia

Nicosia

Paphos

St. Hilarion

Famagusta

Karak

Montréal

Ascalon

Blanchegrarde

Arsuf

Caesarea

Bilbais

Cairo

St Elias

al-Bira

Jerusalem

Bethany

Belmont

Hebron

Darum

Bait Jibrin

Abu Ghosh

al-Qubaiba

Lydda

Jaffa

Tor tosa

Chastel Rouge

Chastel

Blanc

Homs

Crac des Chevaliers

Beirut

Jubayl

Damascus

Sidon

Beaufort

Toron

Safad

Tiberias

Nazareth

Belvoir

Sabastiya

Nablus

Jifna

Jericho

Bethlehem

Gaza

Ibelin

Ramla

Limassol

Tyre

Hattin

Haifa

Acre

Aqaba

Banyas

Bethsan

Scandalion

M

i

r

a

b

e

l

Damietta

Rosetta

Map 17 The Latin east

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

646 hans eberhard mayer

duke. In Jerusalem he was king in fact but not in name. The relations between

state and church remained undefined not only because of the ambiguity of

Godfrey’s position but also because the patriarchate of Jerusalem could not, at

first, be adequately filled. The Greek patriarch had died on Cyprus, but the able

Fleming Arnulf of Chocques, who was placed over the church of Jerusalem,

was so objectionable in terms of canon law that he was not consecrated and

was, in fact, soon removed.

In September 1099 most crusaders made for home. Raymond of Toulouse

was driven by Godfrey first from Jerusalem, later out of south-western Palestine,

and went to Syria and Lebanon. Godfrey, who died on 18 July 1100, had had

only one year in which to rule. He had not enough fighting power left to do

more than hold Jerusalem, Jaffa, Lydda and Ramla, Bethlehem and Hebron.

These were islands in a sea of hostile Muslims. Yet when Bohemond’s nephew

Tancred subjected large parts of Galilee to Christian rule Godfrey could per-

suade him to hold them in fief from him. The demographic structure was totally

unsatisfactory and remained so, more or less, at all times. The largest elements

in the population were the Muslims and the Syro-Christians but it is impossible

to know which of the two were more numerous in the open country whereas

in the cities the Syro-Christians certainly outnumbered the Muslims who, like

the Jews, were totally barred from Jerusalem. The term ‘Syro-Christians’, the

Suriani,very often met with in crusader documents, is vague and it meant

different things at different times and in different places. Generally speaking it

lumped together all Christians ‘not of the law of Rome’. For most purposes this

was enough in a country where the deepest social gap was between Frank (i.e.

crusaders or their offspring) and non-Frank. The vagueness appears when we

try to differentiate. Inasmuch as the sources allow a generalization the term re-

ferred to eastern Christians with Arabic language and – in most cases – Syriac

liturgy, more particularly, and following a rough geographical distribution

of predominant creeds from north to south, to heretical Monophysite Jaco-

bites in the north, heretical (until 1181)Monothelite Maronites in Lebanon

and schismatic Greek Orthodox in the south. Above them the European

ruling class of Catholic creed, known as Latins or Franks and divided into

clergy, nobility and personally free burgesses, remained numerically very small,

but this Staatsvolk monopolized all political rights although in very different

degrees.

To make things worse, the Franks were very unevenly distributed through-

out the country. There was a heavy concentration in the cities; in fact the

nobility was largely absent from their landed estates which were run by native

administrators. Contrary to received opinion it has recently been shown that

the Franks in the open country did not live in total segregation from the na-

tive Syro-Christians but that they rather settled in areas where Syro-Christians

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Latin east, 1098–1205 647

had already lived in pre-crusade days and continued to live together with the

Franks in the same villages. The Frankish population was thinnest where, for

security reasons, it was most badly needed, namely on the desert fringe east

of Galilee, of the Jordan river and the Dead Sea. Given this deficiency in an

adequate defence it was of vital importance that the supply lines from Europe

be kept open at least during the shipping season from spring to autumn. This

required the conquest of the coast. Godfrey clearly recognized this problem

and, in order to buy Pisan naval support, he had to give in to the unrelenting

pressure of the church now under the rule of Daimbert, a former archbishop

of Pisa, and make over to him a principality in successive stages.

After Godfrey’s death his vassals, originating mostly from Lorraine and

northern France, prevented the implementation of these donations and success-

fully invited Godfrey’s brother Baldwin to come from Edessa. On Christmas

Day 1100 he was crowned as the first Latin king of Jerusalem. His solemn be-

haviour contrasted sharply with his scandalous married life in three marriages.

An incessant warrior, he ruled his vassals with an iron fist and became the

true founder of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem. With the church he dealt in

pre-Gregorian fashion attributing to himself the control of ecclesiastical rev-

enues and riding rough-shod over several patriarchs. But he also energetically

supported the endeavours of Arnulf of Chocques, canonical patriarch after

1112,toreform the church of Jerusalem. In 1101 he consolidated the predom-

inantly Lorraine–northern French character of the kingdom by pushing the

Norman Tancred out of Galilee. By 1110, when he took Beirut and Sidon, he

had conquered most of the coast. In these two towns the Muslim inhabitants

were, for the first time, given a choice between emigration and remaining un-

der Frankish rule, a remarkable change, dictated by necessity, of the previous

policy of extermination. Particularly important was the conquest of Acre in

1104.Itgave the kingdom the first safe harbour and the town grew quickly into

the economic centre of the kingdom; by 1120 it had spilled over the city walls

into a suburb. By 1105 King Baldwin I had stopped the threat of an Egyptian

reconquest in a series of battles near Ramla.

Indecisive fighting in the regions east of the Sea of Galilee came to an end

in 1108–10 when Baldwin and Damascus set up a kind of no-man’s land with

a condominium over the northern Transjordan, the Jaulan and the Lebanese

plain of Biqa‘ in which the revenues squeezed from the peasants were divided.

In spite of temporary violations this system lasted until 1187, although neither

side had considered it as final. From 1110 to 1113 Baldwin successfully opposed

agreat Muslim coalition seriously menacing his kingdom. He was saved by

the death of his leading opponents. This gave him the chance in 1115 and 1116

to intervene seriously for the first time in the southern Transjordan, which he

secured by building the great castle of Montr

´

eal.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

648 hans eberhard mayer

The price for these startling successes was heavy. Following precedents al-

ready discernible under Godfrey, Baldwin embarked on a policy of buying the

necessary naval support, which only the Italian maritime republics could give,

by grants which not only gave them freedom from, or large reduction of, taxes

and customs but also quarters of their own which, at least from 1124, became

increasingly autonomous from state intervention in which they enjoyed their

own consular jurisdiction over everything apart from certain crimes, the most

offensive of which normally reserved for royal jurisdiction.

In 1113 Baldwin concluded a very valuable alliance with Sicily by marry-

ing Adalasia, the mother of Roger II, who also brought much desperately

needed money. But the marriage contract envisaged the succession of Roger

in Jerusalem should there be no children and Baldwin never had any. In 1117

the church and the vassals, using the fact, formerly conveniently overlooked,

that Baldwin’s former wife was still alive and the marriage undivorced, forced

him to repudiate Adalasia, thus revoking the Sicilian alliance. It was the first

sign that the king had become politically vulnerable. In the following year

the vassals forced him to abandon a campaign to Egypt which he refused to

conduct according to their wishes. On the way back he died from an old

wound.

He was succeeded by his kinsman Baldwin II. But part of the nobility at first

offered a stiff opposition to this and attempted to place Baldwin I’s brother

Eustace III of Boulogne on the throne. Civil war was barely averted. Internal

consolidation now followed the political expansion of the previous reign. The

king quickly made peace with the church at the council of Nablus in 1120,

releasing ecclesiastical tithes from royal and baronial control.

The king’s main concern was the Syrian north. He himself had been ap-

pointed count of Edessa from 1100 onwards. The Franks had been weakened

byaseries of misfortunes. Bohemond I of Antioch was a Muslim prisoner

from 1100 to 1103 and his nephew Tancred became his regent. He secured

Antiochene possession of Cilicia and permanently added the port of Latakia

in 1108. After Bohemond’s release in 1103 an attempt by the united Frankish

north to cut off Aleppo from the Seljuq bases in Mesopotamia was stopped

short by the Frankish defeat at the Balikh river in 1104, which destroyed the

legend of Frankish invincibility and brought Baldwin of Edessa into Muslim

captivity. Edessa became for a time a dependency of Antioch and Tancred once

more took the regency of Antioch when Bohemond went to Europe in 1105 to

enlist support against growing Byzantine pressure on his principality from the

north. But his crusade against Durazzo on the Adriatic coast ended in utter

failure and with such a humiliating peace treaty, never in fact enforced, that

Bohemond did not dare show his face again in Antioch and died in 1111 in his

native Apulia, a forgotten man.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Latin east, 1098–1205 649

When Baldwin of Edessa regained his liberty in 1108 Tancred hesitated

to hand back Edessa. A war between inter-religious coalitions now ensued,

Tancred and Aleppo fighting against Edessa and Mosul: the crusaders had

quickly been integrated into the bewildering Syro-Mesopotamian political

scene. King Baldwin I was asked to come from Jerusalem to act as arbitra-

tor of the Frankish east. He did so in camp before Tripoli, which had been

under siege since 1103, first by Raymond of Toulouse, who had died there in

1105, leaving behind a succession dispute. In 1109 Baldwin I worked out a com-

promise which for a short time split the old count’s Lebanese possessions in

two under the influence of Antioch and Jerusalem respectively. Soon, however,

death, or perhaps murder, reunited the county which then became a fief of the

kings of Jerusalem although it was not formally united with the kingdom and

was often ready to cut these ties. Antioch, in 1109,was left under Tancred’s

rule, its independence from Jerusalem guaranteed. An alternative for Tancred

was provided in Galilee, should Bohemond I return, but Tancred had to give

up his claims to Edessa. Then the siege of Tripoli was pressed and the city

capitulated in July 1109. This completed the foundation of the last crusader

state, the county of Tripoli, which was Provenc¸alincharacter.

It was of the greatest importance that the settlement of 1109 established

aprecedent for the kings of Jerusalem to be the supreme arbiters of the

whole Latin east. When King Baldwin I fought against Damascus and Mosul

(1110–13), he was acting as much in the interest of the north as in that of his

own kingdom. More or less by coincidence he was not present when Antioch

and Edessa, now assisted by Aleppo and Damascus, defeated the Seljuqs at Tall

Danith in 1115, which meant the end of the attempts by the Seljuq sultans to

reconquer Syria.

No king of Jerusalem became more involved in Antioch affairs than

Baldwin II. Tancred officially ruled Antioch as regent until he died in 1112.

His successor Roger was formally only regent for Bohemond II, the minor son

of Bohemond I, who was in Apulia. Hardly had Baldwin II become king and

had given his former county of Edessa to his kingmaker Joscelin I of Courtenay,

previously lord of Galilee, when he had to go north, following an appeal for

help from Roger of Antioch, who foolishly joined battle with the Muslims be-

fore Baldwin’s arrival. His army was annihilated in 1119 in what justly became

known as the ‘Field of Blood’ and he himself was killed. Baldwin II now had to

shoulder the regency of Antioch, which he could not shed until Bohemond II

arrived in 1126.Onthe whole he did well for the north but he paid heavily for

it. The regency was unpopular in Jerusalem from the beginning. The vassals

had to go through interminable wars against Aleppo but were excluded by a

formal regency contract from being rewarded with fiefs in the north. As early as

1120 the king had difficulties in obtaining the chief war relic of the True Cross

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

650 hans eberhard mayer

for a campaign to the north. In April 1123 he was captured by the Aleppans and

did not permanently regain his liberty until the summer of 1124.Even then

he stayed in the north until 1125.During his captivity he had been replaced

in Antioch by the patriarch, in Jerusalem by a council of three regents. That

there had not been a constitutional crisis testifies to the solidity of monarchical

institutions in Jerusalem, but the population may, in fact, have preferred the

regency to the rule of a king forever absent.

The regents scored a considerable success when they conquered the impor-

tant port town of Tyre in July 1124 with naval support from Venice. But this

indispensable help had to be bought with enormous concessions. In addition

to the usual privileges Venice obtained its own court over all cases involving

Venetians, except mixed cases with a Venetian plaintiff which were reserved

to the king. Venice also received one third of the town’s contado.Astandard

of Italian accomplishment had been set by which other Italian maritime re-

publics would measure their own success. But these grants seriously affected

the jurisdictional, in fact even the political, coherence of the state.

In 1126 Baldwin II could at last surrender his regency in the north, but he had

to resume it in 1130 when Bohemond II was killed in battle, leaving behind an

infant daughter Constance. On the Muslim front Baldwin’s last years, although

troubled by internal revolt, were uneventful after an expedition against Dam-

ascus had failed miserably in 1129.Atthis time, after a precarious existence of

nearly ten years, the military order of the Knights Templar gained recognition

by the church, although it took another decade until its organizational frame-

work was complete. The Templars’ future rivals, the Knights Hospitallers, were

older and went back to an Amalfitan hostel in Jerusalem of pre-crusade days.

While the Templars were warriors from the beginning, the Hospitallers, who

never gave up their charitable functions, took on military duties in the Holy

Land from 1136 on; by 1154 their organization was complete. Both orders could

soon draw on large revenues in Europe and added a very useful new element

to the kingdom’s fighting power both in men and in maintenance of many big

castles.

The king died in 1131. There being no sons he had provided for his succession

by creating a system of joint rule for his eldest daughter Melisende and Count

Fulk of Anjou, her husband since 1129.

Responsibility for the north rested on Fulk just as it had done on the two

Baldwins. Repeatedly he had to ward off attempts by the dowager princess Alice

of Antioch, another of Baldwin’s daughters, to establish herself as ruler at the

expense of her own daughter Constance. In the course of these machinations

Alice was not above seeking, or flirting with, allies wherever she could find

them: Edessa, Tripoli, the patriarch, but, more dangerously, Byzantium and

even Mosul. These troubles so weakened Antioch that Cilicia was lost first to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008