Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Norman Sicily in the twelfth century 471

had a personal duty to serve, irrespective of their property, as their ancestors

had done in the days of the Lombard princes. Normans and Lombards differed

too in their customs governing inheritance, marriage and the status of women.

Partible inheritance remained the norm among those of Lombard descent,

primogeniture ruled among those from Norman and French antecedents. In

Lombard law women were always legally minors, who needed the consent of a

male guardian before undertaking any legal transaction. Women living under

French or Roman law were freer to act on their own behalf.

Thus while the kingdom of Sicily had by the late twelfth century become

an accepted part of the European political scene, and possessed an effective

system of government, it was unified, but remained far from uniform. In this

it reflected the diversity of its origins, and the cosmopolitan society at the

crossroads of the Mediterranean which the Normans had conquered in the

eleventh century, and which a great ruler had welded forcibly together after

1130.But the years after 1189 were to see the unity of the kingdom under threat,

and it was ultimately unable to resist the renewed attack of the German empire.

sicily, the mediterranean and the western empire

The nostalgic reminiscences of later writers, who saw the reign of William

II as a golden age of peace and prosperity, were conditioned by later events.

William died childless on 17 November 1189,atthe age of thirty-six. The result

was five years of conflict before the kingdom was conquered by the German

emperor Henry VI, and after his equally premature death, aged thirty-two

in 1197, there was more than twenty years of intermittent anarchy. But this

was by no means inevitable, nor does it suggest that the Sicilian kingdom was

intrinsically flawed.

William II’s later years saw the kingdom internally at peace, but deploying

an increasingly ambitious foreign policy. His envoys at the peace conference

at Venice in 1177, where a fifteen-year truce was agreed with the German em-

pire, proclaimed that it was his wish to live at peace with all Christian rulers,

but to attack the enemies of the cross.

62

The Sicilian fleet attacked Muslim

Alexandria in 1174 and the Balearic Islands in 1182 (this latter operation prob-

ably in response to Muslim piracy). In 1185 a full-scale assault was mounted

on the Byzantine empire, which under the incompetent and unpopular rule of

Andronikos Komnenos seemed to be on the verge of collapse. In the event, de-

spite the capture of Thessalonica, this attack failed. But it certainly showed the

determination of William II to be one of the leaders of western Christendom.

So too did his prompt despatch of naval aid to the crusader states after the fall

62

Romuald of Salerno, Chronicon sive Annales,p.290.Cf. Houben (1992), especially pp. 124–8.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

472 g. a. loud

of Jerusalem to Saladin. The high status of the king of Sicily was confirmed by

two diplomatic marriages, that of the king himself to Joanna, the daughter of

Henry II of England, in 1176, and of his aunt Constance, Roger II’s daughter,

born in 1154 just after her father’s death (and thus a year younger than her

nephew the king), with Henry, the heir to the German empire, in 1186.

Frederick Barbarossa had first suggested a marriage alliance with the Sicilians

as early as 1173, though papal opposition had ensured that this proposal was

stillborn. But by the conclusion of such a marriage the intrinsic legitimacy of

the Sicilian kingdom was at last recognized by the German empire, its principal

external enemy since Roger II’s coronation in 1130, and thus it is not difficult

to see why William II was prepared to permit it. The price to be paid was the

acknowledgement of Constance as the designated heir to the childless king.

But the significance of such a move should not be over-estimated. William was

still a relatively young man in 1186, his wife was only twenty; he is unlikely to

have abandoned hope of future offspring, and these would have automatically

invalidated Constance’s claim. However, the king did die young, and without

a direct heir.

His death was followed by a split within the kingdom. The claims of Henry

and Constance had a number of prominent supporters, including Archbishop

Walter of Palermo and Count Roger of Andria, one of the two master justi-

ciars of Apulia. But a group of prominent court officials, led by the familiaris

Matthew of Salerno, moved swiftly to elect their own candidate, the other

master justiciar, Count Tancred of Lecce, William II’s cousin (who had been

the commander of the army which had captured Thessalonica in 1185). Tancred

was crowned king on 18 January 1190,amove which had the covert support of

the papacy, anxious to avoid the union of Sicily and the empire.

Although hampered by the Muslim rebellion, Tancred was from the first in

control of Sicily and Calabria. He did, however, face widespread opposition

from the mainland nobility, especially from the principality of Capua and the

Abruzzi, and to a lesser extent from Apulia. He did, however, also have a number

of advantages. Henry VI was preoccupied with domestc affairs in Germany,

and this gave the king time to establish his rule. Most of the higher clergy

(apart from those in the principality of Capua) and the more important towns

supported him, and the latters’ loyalty was made more secure by privileges and

fiscal concessions. His brother-in-law, Count Richard of Acerra, proved an able

lieutenant on the mainland, and his support gave Tancred immediate control

of much of the principality of Salerno. Furthermore, nine of the twenty-eight

counties in Apulia and Capua were vacant, and thus under the administration

of royal officials, in 1189, giving the king a strong foothold in the mainland

provinces, especially in Apulia, and the means to reward potential supporters.

And in November 1190 his chief domestic opponent, Roger of Andria, was

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Norman Sicily in the twelfth century 473

captured and put to death. When Henry VI finally launched his invasion in

the spring of 1191 his army became embroiled in a fruitless siege of Naples

and fell victim to an epidemic, while his naval forces, recruited from Pisa and

Genoa, arrived too late to be of help and proved no match for the Sicilian

fleet.

The withdrawal of the German army allowed Tancred to consolidate his rule.

By 1193 only the Abruzzi region on the frontier held out. The mainland counts

who had opposed him had either gone over to his side (as did the counts of

Molise, Carinola and Caserta), or had been exiled (those of Tricarico, Gravina,

Fondi and the Principato). If the Abruzzi was still a problem, and a base for

German forces to raid into the kingdom proper, his position appeared relatively

secure. That the kingdom’s defences collapsed before a second invasion in 1194

was due almost entirely to two factors. Tancred himself died in February 1194,

leaving a small boy as his heir (William III) and his supporters seem to have

lost heart. And the ransom exacted from King Richard of England gave Henry

VI the wealth he needed to launch another, better organized and coordinated

invasion. This time there were no delays for long sieges, areas of potential

opposition were bypassed, and the fleet arrived in time. Many of Tancred’s

erstwhile supporters immediately submitted, as did the strategic city of Naples.

Messina surrendered to the Pisan and Genoese fleet in September, Palermo in

November, Tancred’s widow abandoned the struggle, and Henry was crowned

king of Sicily on Christmas Day 1194.

Henry’s coronation was followed almost immediately by the arrest of his

erstwhile rival, the unfortunate William III, and a number of prominent nobles

and royal officials, including the sons of Matthew of Salerno, the amir Eugenius

and the admiral Margaritus of Brindisi, all of whom were sent to prisons in

Germany. Despite, or perhaps because of, this brutal action, resistance on

the mainland was not finally extinguished until the capture and execution of

Richard of Acerra in 1196.Afurther revolt in Sicily was brutally suppressed in

the summer of 1197. Although some south Italians who had supported Henry

were favoured – Bishop Walter of Troia was, for example, made chancellor – the

chief beneficiaries of the new regime were his German commanders, men like

Conrad of L

¨

utzelinhard, made count of Molise, and Diepold of Schweinspunt,

the new count of Acerra. Tancred’s government was regarded as illegitimate and

its acts, including the concessions made to the papacy at Gravina in 1192,ofno

legal standing. But if Henry regarded himself as the conqueror of Sicily, ruling

it by right of his imperial title, Constance represented the continuity of the

royal dynasty. In October 1195 she wrote to the pope complaining about various

infringements of the crown’s ecclesiastical rights, including the appointment

of a general legate for the mainland provinces: ‘such things’, she claimed, ‘were

never attempted in the kingdom by the Roman Church under our father the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

474 g. a. loud

lord king Roger and then under the other kings, our brother and nephew’.

63

After Henry’s sudden death in September 1197 she did her best to diminish

the German role in the kingdom. In the years after her death (in November

1198), with the new king a child and the Regno a prey to the rivalries of

local nobles, German adventurers, Pisans and Genoese, Muslim revolt and

papal interference, it was the court officials who had served William II who

represented the principal force for stability and order, and who maintained the

government as best they could through the difficult years of the early thirteenth

century.

64

It was on their work that Frederick II was ultimately to build.

63

‘sub domino patre nostro rege Rogerio . . . et deinceps sub aliis regibus, fratre et nepote nos-

tro . . . numquam in regno talia per sanctam Romanam ecclesiam fuerint attentata’, Constantiae

imperatricis et reginae Siciliae diplomata,pp.12–13 no. 3. Loud (2002), pp. 180–1.

64

Jamison (1957), pp. 146–74, argued that the amir Eugenius was a key figure in this administrative

continuity, up to his death c. 1202, though this has been disputed. For continuity in the chancery,

Schaller (1957), pp. 207–15.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

chapter 16

SPAIN IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY

Peter Linehan

the death of Alfonso VI of Le

´

on on the last day of June 1109 brought a woman

to the throne of ‘all Spain’ for the first time in its history. Or so three weeks

later Queen Urraca described the extent of her authority. ‘All Spain’ in that

summer comprised the area from the Atlantic in the west to the Ebro in the

east and to the north of a line running from Coimbra by way of Toledo to

Medinaceli and the border of the kingdom of Saragossa (the northernmost of

the formally independent taifa kingdoms into which the caliphate of C

´

ordoba

had disintegrated in the previous century), beyond which lay the kingdom of

Arag

´

on and the county of Barcelona. Yet within ten years this description of

the area between the Pyrenees and the sierras of the centre would no longer

apply, and within sixty it would be unrecognizable. By then the north of the

peninsula would be occupied by the five kingdoms of Portugal, Le

´

on, Castile,

Navarre and Arag

´

on which endured until the end of the century and beyond,

and by the end of this chapter further kaleidoscopic transformations will have

occurred. The history of twelfth-century Spain was enacted on constantly

shifting foundations.

This was the case with the reign of Urraca herself (1109–26), one of whose

first acts after her father’s death was to marry Alfonso I, the Battler, of Aragon

(1104–34). This she did ‘during the vintage time’, according to the chronicle

of Sahag

´

un, in fulfilment of arrangements made by Alfonso VI in the last year

of his life. But as well as being uncanonical, the match was unsuitable. Too

nearly related for the pope’s liking, in all other respects the couple were re-

mote. On their wedding night it hailed, the rabidly anti-Aragonese chronicler

reported with satisfaction. (Apart from being dangerously close to the best

wine-growing areas along that stretch of the Duero, Monz

´

on, where appar-

ently the marriage was celebrated, was a place of no ecclesiastical significance:

a doubly inauspicious venue therefore).

1

And, sure enough, worse followed.

1

Reilly (1982), p. 59.

475

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

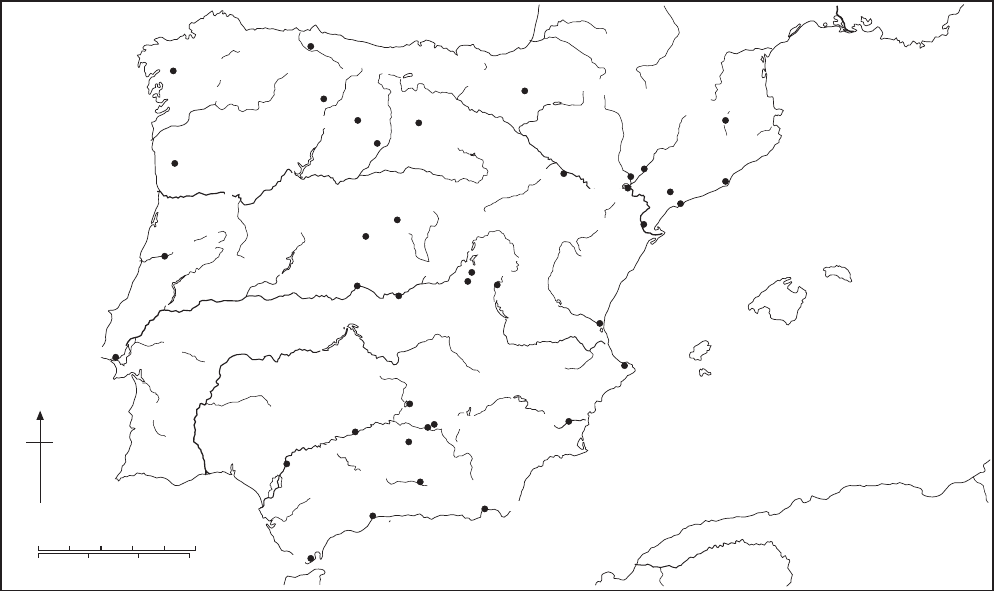

N

0

100

250 km

0

100 150 miles

50

50

150 200

P

Y

R

E

N

E

E

S

B

A

L

E

A

R

I

C

I

S

L

A

N

D

S

Valencia

Murcia

Denia

Tortosa

Tarragona

Barcelona

Ripoll

Saragossa

Santiago de

Compostela

GALICIA

León

Oviedo

Braga

Coimbra

Tagus

Lisbon

ALGARVE

Algeciras

Malaga

Almería

Granada

Jaen

Baeza

Ubeda

Las Navas

de Tolosa

Calatrava

Córdoba

Seville

Mequinenza

Lérida

Fraga

Ebro

Pamplona

Burgos

Palencia

Talavera

Toledo

Poblet

Cuenca

Ucles

LEVANTE

Huete

Ávila

CASTILE

NAVARRE

Sahagún

Segovia

ARAGON

P

O

R

T

U

G

A

L

S

I

E R

R

A

M

O

R

E

N

A

C

A

T

A

L

O

N

I

A

G

u

a

d

a

lq

u

i

v

i

r

A

L

-

A

N

D

A

L

U

S

Map 11

Spain

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Spain in the twelfth century 477

Within the year the pair were at odds, and the inhabitants of the regions around

the rivers Mi

˜

no, Duero and Ebro found themselves being fought over by their

coreligionists with a degree of ferocity which, according to the same writer, far

exceeded anything ever experienced there at the hands of the Muslims. Urraca’s

marriage was the first of a series of dynastic alliances across the century whose

evident potential for disaster from the outset serves notice on the historian of

the otherness of the world into which he is entering.

Our knowledge of Urraca’s reign derives from two contemporary sources:

the aforementioned chronicle of the Leonese monastery of Sahag

´

un, which

has survived in a much later, and possibly much revised, Spanish translation,

and the Historia Compostellana,awork commissioned by an actor in the ensu-

ing drama, Bishop (subsequently Archbishop) Diego Gelm

´

ırez of Santiago de

Compostela, who had even less cause to recall the Aragonese with affection.

2

We do not have a pro-Alfonsine corrective. We altogether lack an account ad-

dressed from the point of view of the king whose Christian zeal would inspire

him in 1131 to nominate the Order of the Temple as one of his heirs.

3

By way of

compensation we are well supplied with charters. However, because so many

of these are fabrications or have been tampered with, the history of the reign

remains riddled with uncertainties. As does that of the entire twelfth century.

Indeed, in comparison with its second half the age of Urraca and Alfonso VII

is well catered for. Even so, those acquainted with countries rich in chronicles

must allow for the fact that Spain is not.

4

They will look in vain for those

little vignettes which elsewhere reveal more than a hundred charters can. They

will find nothing to match the glimpse of Henry II of England wielding his

darning needle for example. The rulers of twelfth-century Spain come across

as irredeemably two-dimensional figures.

The reign of Urraca was overshadowed by Alfonso VI’s various failed at-

tempts to provide for the succession, and its course largely determined by the

personalities brought in by that much-married monarch to compensate for his

remarkable inability to beget a male heir capable of surviving him. As count of

Galicia, Urraca’s first husband, the Burgundian Raymond of Amous had had

his centre in the remote north-west, where (with the assistance of his brother

Archbishop Guy of Vienne) he secured in 1100 the election of his prot

´

eg

´

eDiego

Gelm

´

ırez as bishop of Compostela. His death in September 1107 left Urraca

awidow of twenty-seven with a one-year-old child, Alfonso Raim

´

undez, the

2

‘Cr

´

onicas an

´

onimas de Sahag

´

un’; Historia Compostellana.

3

Garc

´

ıa Larragueta (1957), ii,p.16:‘qui ad defendendum Christianitatis nomen ibi vigilant’.

4

S

´

anchez Alonso (1947), pp. 119–25, 137–48; Linehan (1993), chs. 7–9.For the sequence of events

related in what follows I am indebted to the works of Soldevila (1962), Valdeavellano (1968) and

Serr

˜

ao (1979), but have not thought it necessary to provide repeated footnote references either to

them or to Bishko (1975) where further bibliographical guidance will be found.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

478 peter linehan

future Alfonso VII, in her care. Since 1097 Count Raymond had been schem-

ing to succeed Alfonso VI himself: the Pact of Succession which, with the

assistance of Abbot Hugh of Cluny, he had made in that year with his cousin,

Henry of ducal Burgundy, husband of Alfonso VI’s bastard daughter Teresa,

had promised Henry a share of a divided kingdom. In 1109 Henry, one of a

number of entrenched interests dismayed by Urraca’s Aragonese marriage, was

firmly installed as count of Portugal, the territory between the rivers Mi

˜

no and

Tagus.

5

By the terms of their marriage settlement (Dec. 1109)Urraca and any child

of the marriage were to inherit the kingdom of Aragon if Alfonso died first.

If Urraca predeceased him he and the child would acquire Urraca’s lands, and

when Alfonso died they would revert to Alfonso Raim

´

undez. The settlement

was a recipe for disaster; resistance had already begun in Galicia, led by the

count of Traba, Pedro Froilaz, the guardian of Alfonso Raim

´

undez. But the

settlement proved a nullity because there was no child. Whereas Urraca bore

Count Pedro Gonz

´

alez of Lara two bastards in the years that followed, Alfonso

may have been either impotent or uninterested. Moreover, developing mutual

antipathy between the couple was not diminished by the Aragonese monarch’s

need to attend to the defence of his kingdom against the Muslim ruler of

Saragossa. On Teresa’s behalf, Henry of Portugal fomented trouble between

1110 and his death in May 1112,regularly shifting his support from the king to

the queen and back. But the situation was transformed in late 1111 by Urraca’s

recovery of Alfonso Raim

´

undez, the symbol of legitimacy, and by mid-1112 the

marriage was finished.

6

Not until the 1470s would the opportunity of achieving

Christian unification across the Ebro recur.

Urraca spent the rest of her reign striving to recover the authority which

Alfonso VI had bequeathed to her. In February 1117,atthe council of Burgos

held under the presidency of the papal legate Cardinal Boso of S. Anastasia,

the canonical rules relating to consanguineous marriage were reiterated, rules

of which neither party had been unaware in 1109 but with which it now suited

both of them to conform. On the same occasion a truce of a sort appears to

have been reached whereby each undertook to leave undisturbed the other’s

conquests, Alfonso’s in Castile and Urraca’s in Vizcaya and Rioja. However,

the queen had not only her former husband to contend with but her half-

sister Teresa and Diego Gelm

´

ırez (raised to metropolitan rank in 1120)as

well, and above all Alfonso Raim

´

undez, the election of whose uncle Guy of

Vienne as Pope Calixtus II in 1119 provided an ally even more powerful than the

prelate of Santiago. In 1120–1 Cardinal Boso returned to Spain with instructions

either to constrain Urraca to liberate the archbishop and restore his castles and

5

Reilly (1982), pp. 3–62.

6

Ibid., pp. 63–86.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Spain in the twelfth century 479

extensive territorial ‘honour’ or to impose sentences of excommunication and

general interdict on her and her kingdom. By then the focus of Alfonso the

Battler’s attention had anyway shifted to his ownkingdom and to the Almoravid

presence in the Ebro valley. Here he was assisted by contingents of Gascons and

Normans, notably Count Gaston V of B

´

earn and Count Rotrou of Mortagne

(Perche), whose numbers were greatly swollen in 1118 when Gelasius II issued

crusading indulgences at the council of Toulouse. The capture of Saragossa

(Dec. 1118), the greatest feat of Christian arms since the reconquest of Toledo,

was largely due to these trans-Pyrenean warriors, and notably to the count

of B

´

earn and the experience of siege warfare he had acquired at Jerusalem in

1099.

7

At Jerusalem the Muslim defenders had been massacred. At Saragossa they

were permitted either to leave or to remain on terms. Alfonso the Battler was

overstretched. The ambitions of the victor of Saragossa extended to all parts of

the taifa kingdom, as far as Tudela and Calatayud in the west and L

´

erida in the

east. In 1125–6,atthe urging of Mozarabic Christians of the deep south, he led

an army as far as Granada, defeated the forces of the governor of Seville near

Lucena and returned to Saragossa bringing with him thousands of Christian

families to settle his new territories in the Ebro valley. But in order to be

able to afford such forays, economies had to be made elsewhere and in 1122–3

Alfonso relinquished the hold which he had fitfully exercised over Toledo since

1111, thereby enabling the Leonese to exploit Almoravid weakness and launch

an attack on the city of Sig

¨

uenza, which fell to them at the beginning of

1124.Significantly it was not with Urraca but with Alfonso Raim

´

undez that

his agreement to withdraw from Toledo was reached. The queen’s political

initiative after 1117,inreconciling her son to herself and making him the agent

of her authority in the trans-Duero and Toledo, has been acclaimed for its

brilliance.

8

This is perhaps excessive: from what can be inferred from the as

ever patchy evidence it would appear that Alfonso Raim

´

undez was determined

to be neither his mother’s man nor the archbishop of Santiago’s, but his own.

On 8 March 1126 Urraca died in adulterous childbirth. She was forty-six.

Alfonso Raim

´

undez, who succeeded her as Alfonso VII (1126–57), had served

a long and tough apprenticeship and alone of his line had his exploits recorded

in a contemporary chronicle, the ‘Chronica Adefonsi Imperatoris’.

9

Even in

his mother’s lifetime Alfonso had used the imperial title. He appears to have

done so for the first time in 1117, shortly after entering Toledo;

10

which, if

so, was not fortuitous for the Leonese monarch was strongly attached to the

7

Ibid., pp. 87–204; Lacarra (1971), pp. 59–68.

8

Reilly (1982), pp. 173–80, 360.

9

The most recent study of the reign is that of Recuero Astray (1979).

10

Reilly (1982), p. 126;Garc

´

ıa Gallo (1945), p. 227 n. 94.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

480 peter linehan

old Visigothic capital. Historians have long debated the question of the use

of imperial nomenclature by the kings of Le

´

on from the 910s onwards. For

Alfonso VI the idea of empire was associated with Toledo. For Alfonso VII,

however, committed as he was to the city in which he would be buried (as

Alfonso VI had not been), the idea of empire represented something else: not

an evocation of the past history but the acknowledgement of present politics. At

Whitsun 1135 it was not Toledo, it was Le

´

on that hosted his imperial coronation,

thereby proclaiming the fact that ‘King Garc

´

ıa [Ram

´

ırez] of Navarre and King

Zafadola of the Saracens [Abu Ja

far Ahmad ibn Hud, ruler of Rueda] and

Count Ram

´

on [Berenguer IV] of Barcelona and Count Alphonse of Toulouse

and many counts and dukes of Gascony and France were obedient to him in all

things (in omnibus essent obedientes ei).’

11

The twelfth-century peninsular ruler

to whom Spanish posterity would refer simply as ‘the emperor’ adopted the

imperial title in order to express the extent of his feudal authority either side

of the Pyrenees and either side of Spain’s religious divide. Though he was only

nine years into it in 1135 his thirty-one-year reign is perhaps best approached

by treating that occasion as its central event.

During those first nine years Alfonso VII was occupied in undoing the dam-

age of the previous seventeen. On his accession in 1126 even Le

´

on, the capital

of his ancestors, offered resistance. To the east there were Aragonese garrisons

at Burgos and beyond. However, having brought the Leonese to order, his first

move was westwards for discussions with Countess Teresa of Portugal. With her

and her paramour the king ‘made peace...until the appointed time’ (usque

ad destinatum tempus).

12

And so he did with others. But what, if anything,

would these arrangements be worth? As soon as the king was out of sight his

sword counted for no more than a knife that had passed through warm butter.

Following the chronicler’s account (on which for these years we are wholly

dependent) we turn east. From Carri

´

on and Burgos the locals sent the king (‘of

Le

´

on’) friendly signals ‘because he was their natural lord’ (i,p.8). The Aragonese

custodian of Burgos was loath to surrender, whereupon the Christians and Jews

of the place turned him out and handed him over to Alfonso. When he heard of

this the king of Arag

´

on was furious. But the game was up, the Battler knew it,

and with a sudden crescendo the ordinarily flat prose of the chronicle records

the fact. Messengers were sent through Galicia, Asturias, Le

´

on and Castile sum-

moning a great army, and the king of Arag

´

on bowed to the inevitable, at T

´

amara

tamely pleading for just forty days in which to withdraw his troops (i,pp.9, 10).

From other evidence, however, it appears that the chronicler’s account of

the ‘Peace of T

´

amara’ is less than entirely credible, and that far from returning

empty-handed the Aragonese envoys brought back with them Alfonso VII’s

11

Chronica Adefonsi imperatoris,bki, ch. 70.

12

Ibid., bk i, ch. 5.i.5.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008