Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The papacy, 1122–1198 381

preoccupation of the last years of Alexander III’s pontificate and the policy of

conciliating Frederick I survived his death (1181). Of Alexander’s five succes-

sors in the years 1181–98 only one had not been a member of the Alexandrine

college, that closely knit body of advisers on whom (according to Cardinal

Boso) Alexander had so much depended. The exception was Urban III (1185–

7), Hubert Crivelli, formerly archbishop of his native Milan. Urban III was

a bitter enemy of the emperor and his brief pontificate witnessed a renewal

of the conflict of the papacy with Frederick Barbarossa. Urban attempted to

revive the Lombard League and strove, by raising the issue of the freedom of

the German church, to sow dissension among the ecclesiastical princes in the

German kingdom.

403

This bellicose stand for the freedom of the church by a pope who during

the schism had been a member of the circle of the exiled Archbishop Thomas

Becket of Canterbury was in marked contrast to the strategy of his predecessor

and his successors. Lucius III (1181–5) was a former member of the ‘Sicilian

party’ and, as Cardinal Hubald of Ostia, the most influential figure in the

Alexandrine curia.

404

At the conference of Verona (1184)heattempted to set-

tle with the emperor all the questions left unresolved in 1177, succeeding in

agreeing at least on the necessity of a new crusade and on new measures against

the spread of heresy.

405

Lucius had no choice but to be conciliatory towards

Frederick Barbarossa. Exiled from Rome by yet another dispute between the

curia and the senate, he found himself observing the dismantling of the al-

liances which had achieved the Alexandrine victory. The emperor negotiated

in Constance a permanent peace with the Lombard cities (1183) and arranged

a marriage alliance between his son, Henry VI, and the Sicilian princess Con-

stance, daughter of Roger II and aunt of William II.

406

The successor of the ag-

gressive Urban III was Gregory VIII (1187), the former chancellor of Alexander

III with the reputation of being well-disposed towards Frederick.

407

His elec-

tion immediately brought an end to the conflict that Urban III had provoked

with the emperor. The aims that Gregory VIII pursued during his short pontif-

icate were the reform of the church and the launching of a crusade and for both

of these peace with the empire was the prerequisite. When Gregory’s crusading

plans were realized by his successor, Clement III, Frederick Barbarossa was the

first monarch to pledge his participation in the Third Crusade. The emperor

took the cross in ‘the diet of Christ’ (curia Christi) which he summoned to

403

Wenck (1926), pp. 425–7;Hauck (1952), pp. 319–22; Pfaff (1981), pp. 175–6.

404

Zenker (1964), pp. 22–5, 153; Pfaff (1981), pp. 173–4.

405

Foreville and Rousset de Pina (1953), pp. 191–2; Pfaff (1981), pp. 164–5.

406

Peace of Constance, MGH Constitutiones, i,pp.408–18.Onthe papacy and the marriage of Henry

VI and Constance see Baaken (1972).

407

Robert of Auxerre, ‘Chronicon’, p. 252;Gervase of Canterbury, Chronica 1187,p.388.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

382 i. s. robinson

Mainz (27 March 1188), together with the papal legate and official crusading

preacher, Cardinal Henry of Albano.

408

The pontificate of Clement III (1187–91) was a period of momentous change

in the curia and in the political situation of the papacy. Clement concluded

the treaty with the Roman senate (31 May 1188), which restored papal lordship

over Rome after forty-five years of intermittent conflict with the commune.

409

Between March 1188 and October 1190 he appointed approximately thirty car-

dinals, the majority of whom were connected with the great Roman families.

410

It was during this period of radical change in the character of the college that

the curia was thrown into confusion by the death of the papal vassal, King

William II of Sicily (18 November 1189). The premature death of the childless

king threatened the papacy with the succession of his aunt Constance, wife of

Henry VI, who in June 1190 was to succeed his father to the German throne.

For the rest of the century the papal curia was preoccupied with the problem

of ‘the union of the kingdom with the empire’ and with plans to prevent the

kingdom of Sicily from falling into the hands of Henry VI.

411

The cardinals,

however, did not approach this problem in a spirit of unity. Events were to

demonstrate that Clement III’s enlargement of the college had introduced car-

dinals with attitudes towards the Sicilian succession and towards Henry VI as

sharply divided as those of the 1120s and 1150s. Not only had he, for example,

recruited Peter, cardinal priest of S. Cecilia, a prominent supporter of Henry

VI. He had also appointed Albinus, cardinal bishop of Albano, who was the

close friend of Tancred, count of Lecce, the illegitimate cousin of William II,

who was elected as their king by Sicilians rebelling against Queen Constance.

412

These divisions seem to be reflected in the constantly shifting papal policy

of both Clement III and his successor, Celestine III (1191–7). Clement was

alleged to have recognized the claim to the Sicilian throne of Tancred of Lecce

in preference to that of Constance;

413

but he also promised to crown Henry VI

emperor and received him with honour when he entered Italy.

414

Celestine III

performed the imperial coronation promised by his predecessor (15 April 1191);

but he also recognized Tancred as king of Sicily (spring 1192). (The decision

to recognize Tancred was taken when Cardinal Peter of S. Cecilia and other

supporters of the emperor were absent from the curia.)

415

Celestine gave support

to princes rebelling against Henry VI in Germany;

416

but he failed to adopt

strong measures against the emperor in the case of King Richard I of England

408

Friedl

¨

ander (1928), p. 39; Congar (1958), pp. 49–50.

409

Liber censuum, i,pp.373–4.Seeabove p. 366.

410

See above p. 364 and n. 316.

411

See above p. 368.

412

Friedl

¨

ander (1928), pp. 119–23; Pfaff (1974a), p. 360.

413

Richard of S. Germano, ‘Chronica regni Siciliae’ 1190,p.324; Arnold of L

¨

ubeck, ‘Chronica’ v.5,

p. 182.

414

Pfaff (1980), p. 278.

415

Pfaff (1966), pp. 342–4.

416

Zerbi (1955), pp. 98–9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The papacy, 1122–1198 383

(spring 1193). Henry VI had invited excommunication by holding Richard

to ransom, although the latter’s status as a crusader placed him under the

papacy’s special protection. When the pope debated this case with the cardinals,

however, the majority – consisting of imperial supporters and moderates fearing

an escalation of the quarrel with the emperor – opposed excommunication.

417

This paralysis of the curia came to an end with the sudden death of Henry VI

(28 September 1197). The flurry of purposeful activity in the last three months

of Celestine III’s pontificate revealed that the imperial sympathizers had lost

their influence. The opponents of the late emperor now enjoyed the support

of a majority in the college in their determination to exploit the opportunities

of the interregnum.

418

At the moment of Celestine’s death (8 January 1198) the

papacy unexpectedly enjoyed a political situation more favourable than at any

moment in the twelfth century: a situation that was the fortunate inheritance

of Innocent III.

417

Pfaff (1966), pp. 347–50;Gillingham (1978), pp. 217–40.See also above p. 346.

418

Wenck (1926), p. 464; Pfaff (1974b).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

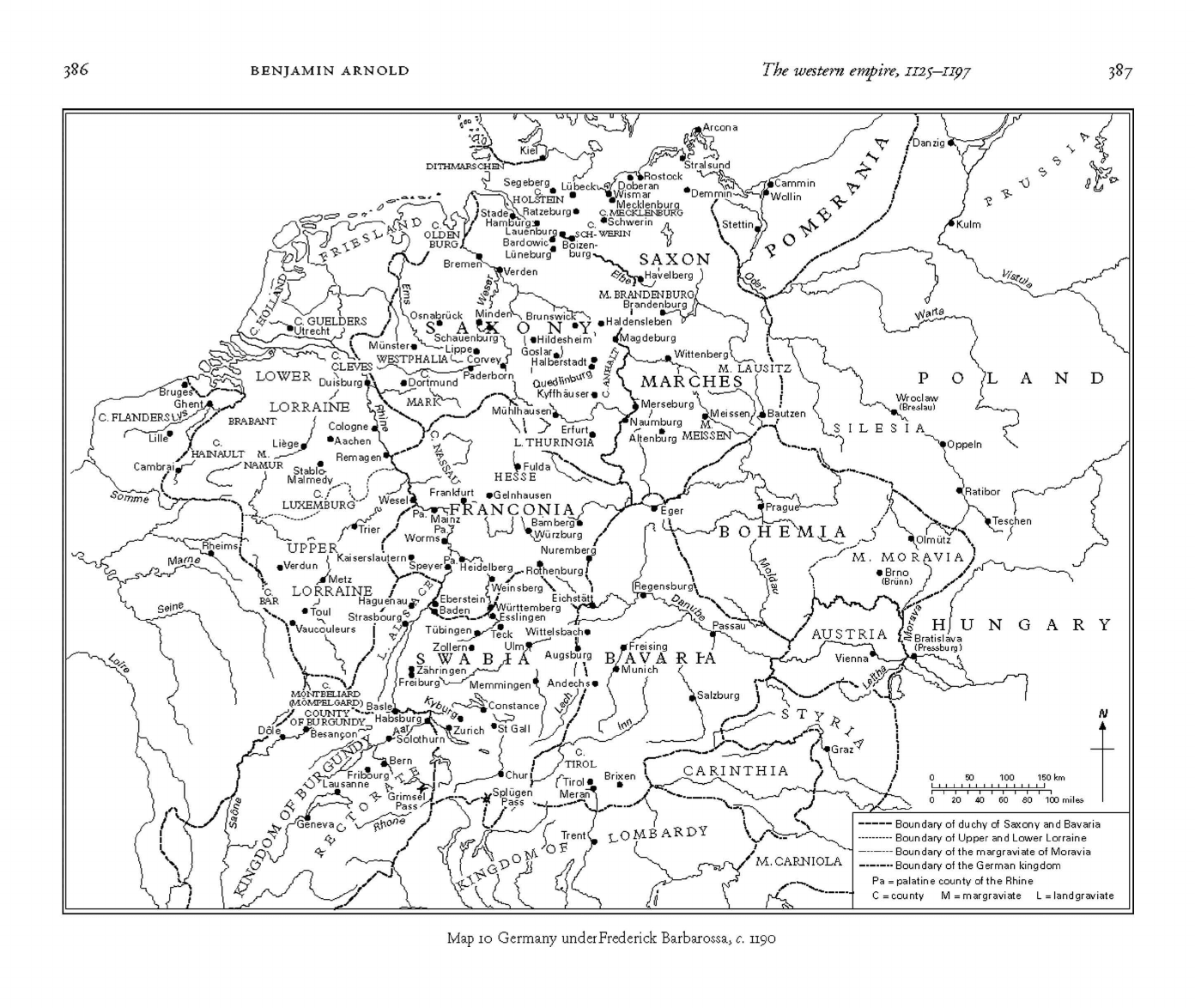

chapter 14

THE WESTERN EMPIRE, 1125–1197

Benjamin Arnold

in 1122 the peace arranged at Worms between Pope Calixtus II and Emperor

Henry V was designed to bring an end to the ecclesiastical, political and military

emergencies which had disturbed the western empire since the 1070s, the series

of confrontations called with hindsight the War of Investitures. The papal curia

was enabled to return its attention to the programme of religious reform, and

the First Lateran Council was celebrated in 1123. The emperor was freed from

the incubus inherited from his excommunicated father Henry IV, and the

preliminaries of the Worms pax committed the princes to assist the emperor

in maintaining the authority and dignity of imperial rule. But the outcome

of such intentions was problematical given the ingrained enmities, especially

between Saxony and the royal court, caused by the War of Investitures. In any

case the restoration of royal authority for which Henry V had striven since

1105 was called into question because the emperor, still a youngish man, died

at UtrechtinMay1125.His marriage to Matilda of Normandy had proved

childless, so it was necessary for the princes of the empire to set about electing

anew king.

electoral procedures in the twelfth century

In the early summer of 1125 the German bishops and secular magnates who had

gathered in Speyer for the obsequies of Henry V sent letters to the other princes

of the empire inviting them to Mainz in August for the election of the next king.

A surviving version, to Bishop Otto I of Bamberg, requested him to pray for a

candidate who would liberate church and empire from the oppression under

which they had laboured hitherto. Such explicit criticism of the two preceding

emperors was undoubtedly the work of Archbishop Adalbert I of Mainz, whose

office traditionally conferred upon the incumbent the leading voice in German

royal elections. As royal chancellor and favoured counsellor, Adalbert had been

promoted to the see of Mainz by Henry V, but subsequently they had quarrelled

384

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The western empire, 1125–1197 385

about the respective rights and properties of the archbishopric and the crown,

and the archbishop had been arrested and imprisoned. Upon his release he

continued to make trouble for Henry V, and the form of expression in the

letter to the bishop of Bamberg was probably intended as a warning against

Duke Frederick II of Swabia, the deceased emperor’s nephew and nearest male

relative, who confidently expected to be elected to the vacant throne. It was

Duke Frederick who had acted as the emperor’s representative in the Rhineland

during the feuds with Archbishop Adalbert, even besieging him in his cathedral

town.

The chronicler Ekkehard of Aura reports that upon his deathbed at Utrecht,

Henry V ‘gave advice as far as he was able about the state of the realm and

committed his possessions and his queen to the protection of Frederick as

his heir’.

1

In this attempt to designate the duke of Swabia as successor to

the western empire, the best that the emperor could hope for was Frederick’s

success at the election. But the duke’s younger half-brother, Bishop Otto of

Freising, explained a generation later that ‘the high point of the law of the

Roman empire is that kings are made not by descent through blood ties but in

consequence of election by the princes’.

2

Duke Frederick II nevertheless had

powerful pretensions, and his previous enmity with Archbishop Adalbert need

not have prevented a rapprochement over his election to the throne. However,

the principal sources for the 1125 election, the anonymous Narratio de electione

Lotharii and Otto of Freising’s Chronica or History of the Two Cities, indicate

that Margrave Leopold III of Austria, a price noted for his personal sanctity,

was put forward as a compromise candidate. Like the duke of Swabia, the

margrave stood close to the previous ruler through his marriage to Henry V’s

widowed sister Agnes of Swabia, Duke Frederick II’s mother. Leopold III’s

election would have fulfilled the desire expressed to the bishop of Bamberg

that a man of peace and a friend of the church should be elected.

A candidate with much more formidable political pretensions in the empire,

Duke Lothar of Saxony, was also acceptable to the most influential electors, yet

there were also grounds for distrusting him. The duke’s high-handed methods

had posed a real threat to the see of Mainz’s extensive possessions in Saxony and

Thuringia, and the other prince whose dignity also conferred great electoral

influence, Archbishop Frederick I of Cologne, was frightened of Duke Lothar’s

authority over the see’s suffragans in Westphalia. So the archbishop of Cologne

put forward Count Charles the Good of Flanders as a candidate. In the end the

archbishop of Mainz appears to have conceded that the Saxon duke’s promotion

would be the safest means of excluding Frederick of Swabia, and the majority in

a college of forty princes duly elected him as Lothar III. Although Archbishop

1

Ekkehard, ‘Chronicon universale’ for 1125.

2

Otto of Freising and Rahewin, Gesta Friderici ii, 1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3%6

BENJAMIN

ARNOLD

The

wettern

empire,

112$-iipj

387

DITHMARSCHEN^

-

" Stralsund

^y~*— j \f ^ ^ (J^,

«»

^ <

.'yVo

. u -

"Mecklenburg

' I y ' ) *

-icS=

oa S

StOi

/Stade«VRatzeburg« c.MECKLENBURG

\ V, J J

r^~W

cO7/

Hamburg»

c

«Schwerin

.

\stettinj)

-*>v /

/»Kulm

/

J^~ll

cV^rk

OLDEN/

Lauenbura-scH.wEEiN

O V 7/ ~ V V /

^A~ll ^V?" 7

EURO/

Bardowic" goizen-

S \ / O ^ ...

/fVU*

rW

Bre

>L

Lünebur9

buf

3^.

SAXON

y ^ _T

J,Sp

\ V

ift

rden

4^-lberg)

v^^^L

) ^

/-fj fi-i

J—M. BRANDENBURG/

Vi^T^^

W--"^

N. /

/

s/^k y ) X * *} r

Brandenburg

A-v

TT < \

/AjP r^ncincn? )\\Osnabrück MindenV, BrunswicFN

ujj—.i.iiTV'

1

—"v.

Vi I

^JK^-^

1

/

s^^^-_C.

CjUbLDEKo

/ I \ o* A t vr /-\

XT

a^j

«Haldensleben

y

N w S \ \

Ao

J*Utrecht

P

_,/

( \ a.. A JA Ü N *Y, /, , , 17 ^ \ X

tJ^>y

'~

;

-V

J

f tT- 1 V

Schauenburg

"i

I

«Hildesherm «"Magdeburg

W [w, . ) \

^VvN™^/

—-N

\

Munster«

i

;

mP

.

\ X , i I i S N / N

.

WESTPHALIA^Co^eyi

G

Gstadt

•

fh—<

i,,enber9

\

\ 1 C

CS^S

CLEVES

>^~N

^-_^^r

«f

"aioerstaat.

3

j -w

LAUSITZ

\

\

^ST^ LOWER

Du

^

burg

^

^?5orWmT^

derborn

i

ou

«№<*^

$\

MARCHES

i 1 N ^

PO)LAND

^

rU

9"*^"~'3>

/

i \

^ARV~\ /'"VV Mfhäuser.

6 V

<*

'

~\A

i j )

Wroclaw

i

A

Ghent**

v^r T

fiPP

ATMP

v-n

s

"^kin

\ /

.... p*^-

\

>T\_^.

»Merseburgs

l\ ; /

fRrf.^lau,

/c.FIANDERS^J^^^

08

-

8

-^

1

^

X—^

'*

h

vV^Xaibur,

> eissen^

Bautzen

<,

^1

^^VtT

BBABANT

/

Cologne

¿1

^VT \\ >

Erl^t.

/^^^„£^0'^

I L E S I A 5^

I

Lllle

X O.

Liegen

'Aachen!

J

%^

L.THURINGIA*

^

Altenburg

MEISSEN^

^ ^

^>0

PP

eln

\ /

C

/HAINAULT

M.^'

Remagen

V

?»

J ! C 1 X

^

\ \ ^

,J\ Cambrai^

^NAMUR

^ A

V

FuldaX^N

^ ) ^ L V-~-^ \ y\

\

1

' f

Malmedy^

HESSE

^^>-^X,

K

C~~-*i^-~^\

} 1 J ?

S^^f\-.^_

/

c

-/'

will

Frankf

"

rt

»Gelnhausen

\ A^J^

V^~A

C

IfTV \Ratibor

r—^^"^

i

^<

^LUXEMBURG

/7^

F

VANCONIArV^

f

^T

a9U

^~

\ \ K » f

j—^

/

Mainz

< I

V

Bamberg.

/ -

l\ (Z

^Vr^TV.

,

T

»

' V >^J

Vreschen

}

^C™-4,

V . H""/

Worm?/

l^V-burg/

H

WB

O

H

E^M JA

J

>OlC?f\

^

/

\

^

PE

<

R

Ka,serslau,

e

rn.

Jw>

^""""V

\ L

XM,

MORAVIA

!

^

\

\

LORRAINE

I M

.fe^N^J^feA

>

1

„

"

Un

"^-V

lj

.

»

\

EAR

J

Haguenaui- EberstemV

.

Eichstätt TN,

j

1

"

^"xSsv,

\\ /

rVj'Vjw

/ N f

\

SJIH1-.

Vv

«Tou|

ct

V

^f/^Baden ^Württemberg

>^

^^fe

\\ f J

k_^T~^

1 \ ^

Strasbourgs^/ —

•*_-*

,

*\Esslingen

J

^

J

^?'

'

\A

7 K U TT V ^ & 1? V

1

\ I

\Vaucouleurs

( <H/

Tübingen-xÄi.

Wittelsbach-

VPassau

/

AUSTRIA

Ho

JT'

i

\ I V V/ —' ,., ! . 1^-^ Y

RlJOiMB

Bratislava

(

\ I \ j .//

Zollern« UlmT^

•

«Freising

! N i ( -—\ \

(Pressbur^)

^^N<V

\ \ \\ S /7/ S f

A

BJA

Augsburg

ß/AVA

RTA

^-«i-^

Vienna*

^V^~v\

N>

1 \ \

4.-.».

i / I

|Zähringeny~~—'

1 [ \

*Munich

/ J

*^^?

t

^

V

X

\

) V

h

c'^SJ

I

/FreiburgV—^Mernmingen* Andechs»

( / \

't~'

l

^>v

^t""^ HZ —-

1

/

j

MONTBEUARD

/ / is k. I \ \

ISalzburg

1 —'

\^N-4L>

(

\ '

J

J

I0MPELGAI

^'BasleV. ^6^r~^%Constance) jf f

\ \ \ j \

m

>

j

V )

^Yy^oJs^^

I)

^ChurLy/-™^

-

Brixen

l

CA RI NTH IA

/V- /' 0 50 100

150 km

!

1 1

-O'Lausanne

^J^^_ .. 1 (

llr

°li

» >«5^ ^ f N. » y

1

I /»

^Ao^^^A^SH"^

-

-A"

v-^^P^\>^

4

"

¿•¿•¿•¿•»»1-

^

/

^N_/ /r$i

v

Y

/-

/

GenevaQ

>*'

_J

i;/^/V

/ I ^

t>.

v V \ *^

Boundary

ol

duchy

of

Saxony

and

Bavaria

(

\ \

Vrcy

] • /

jr»/pjr~~~^

)

TRERIT

>

LOMBAKI>i

yVlAy

Boundary of Upper and Lower Lorraine

I k I / ' ^^Q\ / ^- ^ ]f T^%, pi ^ r *

Boundary

of

the margraviate

of

Moravia

\

^ / /

/J

^

V

^JS.

l(

tÄÖ'P

Ji y^/

M

'

CARNI0LA

Boundary

of

the German

kingdom

I f /| W"

1

" / > C)C

Z*'—r»

< ^-^

Pa

=palatine

county

of the

Rhine

\^

J j j l^f*^ ^

x^.

1

^-^

N^

p 'i \ ^f^^ ^

C

=county

M

=margraviate

L

=

landgraviate

Map 10

Germany

under

Frederick

Barbarossa)

c,

1190

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

388 benjamin arnold

Adalbert had succeeded in depriving his chief enemy of the throne of Germany

and the empire, the author of the Narratio was more interested in proclaiming

that the outcome of the election was the will of God rather than a political

manoeuvre. In twelfth-century political parlance such an explanation could

be taken seriously because the empire was held to exist under the especial

protection of heaven. In 1157, for example, Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa

was to issue a circular in which he appealed to just such principles against the

supposed claim by the papacy to possess the authority to confer the imperial

office as if it were a papal fief:

And since, through election by the princes, the kingdom and the empire are ours from

Godalone, who at the time of the passion of his son Christ subjected the world to

dominion by the two swords, and since the apostle Peter taught the world this doctrine:

‘Fear God, honor the king’, whosoever says that we received the imperial crown as a

benefice (pro beneficio)fromthe lord pope contradicts the divine ordinance and the

doctrine of Peter and is guilty of a lie.

3

When Lothar III died late in 1137, the difficult electoral circumstances of

1125 were repeated. The Saxon emperor left no son, but his son-in-law Duke

Henry the Proud of Bavaria took custody of the imperial insignia and appears

to have been confident of winning the election to the empire. However, two

reports from the pen of Bishop Otto of Freising suggest that Henry the Proud

was even more widely distrusted as a candidate than Frederick II of Swabia had

been in 1125.Since the see of Mainz was now vacant and the new archbishop of

Cologne was not yet consecrated, Archbishop Albero of Trier emerged as chief

elector, and he permitted Duke Frederick’s younger brother to be elected as

Conrad III at an assembly hastily convened at Coblenz in March 1138.Several

princes including the distinguished reformer Archbishop Conrad I of Salzburg

objected to these proceedings, but the new king successfully outfaced his op-

ponents at a court held at Bamberg in May. The Saxon and Bavarian princes

were possibly persuaded by Lothar III’s widow Empress Richenza to accept

Conrad III for the sake of peace. Not long afterwards Duke Henry the Proud

surrendered the insignia, and the claims of the Swabian house to the kingdoms

of Henry V were vindicated after all.

Although the elections of 1125 and 1138 were tense, they need not be inter-

preted as constitutional crises since they reveal that the procedure of the princes

alighting upon a new king by electoral choice was in working order. If Conrad

III’s election at Coblenz was judged by the Saxons and Bavarians to have been

conducted in an underhand manner, then the Swabians and others held Arch-

bishop Adalbert I’s domination of the assembly at Mainz in 1125 to have been

3

MGH Diplomata,Frederick I, no. 186,p.315. The translation is by Mierow and Emery (1953),

pp. 185–6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The western empire, 1125–1197 389

improper. Since they had sons, the new Staufen royal dynasty was enabled

to revert to the method preferred by their Salian and Ottonian predecessors,

election of the successor during the reigning king’s lifetime. Conrad III’s son

Henry Berengar (d. 1150) was elected upon the eve of his father’s departure for

the Second Crusade in 1147;Frederick Barbarossa’s son Henry VI was elected

in 1169 at the age of three; and the latter’s infant son Frederick II was elected

in 1196.

Upon his death in 1152 Conrad III left a son, Frederick of Rothenburg born

in 1144 or 1145, but it was the king’s nephew Frederick Barbarossa, duke of

Swabia since 1147, who was elected. According to Otto of Freising, Conrad III

had ‘judged it more advantageous both for his family and for the state if his

successor were rather to be his brother’s son, by reason of the many famous

proofs of his virtues’.

4

Since this passage occurs in a biography designed to

promote the reputation of the brother’s son in question, the argument is a

little suspect. On the other hand, Conrad had not pressed for Frederick of

Rothenburg’s election after the early death of Henry Berengar either. The

bishop of Freising plausibly pointed out that since the new king’s mother had

been a sister of Henry the Proud, the princes gathered for the election of 1152

‘foresaw that it would greatly benefit the state if so grave and so long-continued

a rivalry between the greatest men of the empire for their own private advantage

might by this opportunity and with God’s help be finally lulled to rest’.

5

In fact

the problems of regional rivalry between prominent princes were much more

complex than the bishop indicates, but he was right to foretell that Frederick

Barbarossa would bring about an effective compromise with Duke Henry the

Lion, Henry the Proud’s heir and his own first cousin, by 1156.

Although the elections of 1125 and 1138 had provided cliques with opportu-

nities to display and perhaps to abuse their power, kings do not appear to have

feared the electoral procedure as such. When Henry VI proposed in 1196 to

abolish it in favour of a hereditary empire, his principal motive seems to have

been an almost eschatological belief that as the true line descended from the

Salians and the Carolingians, the Staufen simply constituted the indubitable

imperial house destined to rule the Roman empire until the end of human

history. Hereditary descent would deftly have incorporated such convictions

into the law of the empire. More than one source suggests that with less haste

the proposal might have been accepted by the princes of Germany because

hereditary right was familiar to them in France and other kingdoms. But while

the princes ruminated the emperor was in a hurry to leave for Sicily in order

4

Otto of Freising and Rahewin, Gesta Friderici i, 71. The translation is by Mierow and Emery (1953),

p. 111.

5

Otto of Freising and Rahewin, Gesta Friderici ii, 2. The translation is by Mierow and Emery (1953),

p. 116.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

390 benjamin arnold

to prepare for the recently proclaimed crusade, so he settled for a traditional

election of his young son instead.

Upon election kings adopted the title Romanorum rex, ‘king of the Romans’,

one of their tasks then being to undertake the expeditio Romana or march to

Rome in order to receive the imperial crown at the hands of the pope. But

the pope did not thus confer imperium upon the German king, as Frederick

Barbarossa was at pains to point out during his altercation with the papal curia

and its legates in 1157 and 1158. The election in Germany counted as election

to the empire in addition to the thrones of Germany, Italy and Burgundy,

but it was not the custom to adopt the style of emperor until the Roman

coronation had taken place. However, royal intitulation often included the

imperial adjective augustus, implying that promotion to the superior title was

only a question of time. The title was improved by Conrad III’s chancery

to rexetsemper augustus, ‘king and ever Augustus’.

6

Conrad III never was

crowned emperor, but in his correspondence with the court of Constantinople

his chancery entitled him ‘Emperor Augustus of the Romans’ in any case.

the meaning of empire and the purpose of imperial rule

When Bishop Otto of Freising wrote that Lothar III reigned as ninety-second

ruler since Augustus, he intended to portray the venerable monumentality of

Roman imperial rule which had supposedly descended lineally to the German

kings. In the twelfth century their version of imperium was being redefined in its

several aspects. Imperium or imperial rule was the personal right of governance

and justice which the king exercised in his three kingdoms. To take examples

from Germany, Lothar III, Conrad III and Frederick Barbarossa in turn referred

to ‘the authority of our imperium’, ‘our imperial authority’ and ‘authority

of empire’ when confirming rights for the monasteries of M

¨

unchsm

¨

unster,

Volkenroda and Wessobrunn respectively.

7

If imperium was the protective legal

authority of the king, then the autocratic potential of such jurisdiction was

again made apparent by students of Roman Law in the twelfth century, the

lawyers of Bologna advising that imperium was in principle limited solely

by divine and natural law. However, a letter of 1158 to the pope indicates

that Frederick Barbarossa took a cautious view of applying autocratic rights

consequentially, at least in Germany: ‘There are two things by which our empire

should be governed, the sacred laws of the emperors and the good practices of

our predecessors and ancestors. We neither desire nor are able to exceed those

6

E.g. MGH Diplomata, Conrad III, no. 184,p.332, 1147.

7

Ibid., Lothar III, no. 54,p.86, 1133, has ‘imperii nostri auctoritate’; ibid., Conrad III, no. 33,p.54,

1139, has ‘nostra imperiali auctoritate’; ibid., Frederick I, no. 125,p.210, 1155, has ‘imperiali auctoritate’

and ‘imperatoria auctoritate’.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008