Lewin Benjamin (ed.) Genes IX

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ments

can act

only

on transcription

units

within the

same domain.

A

domain

might

con-

tain

more than

one transcription

unit and/or

enhancer.

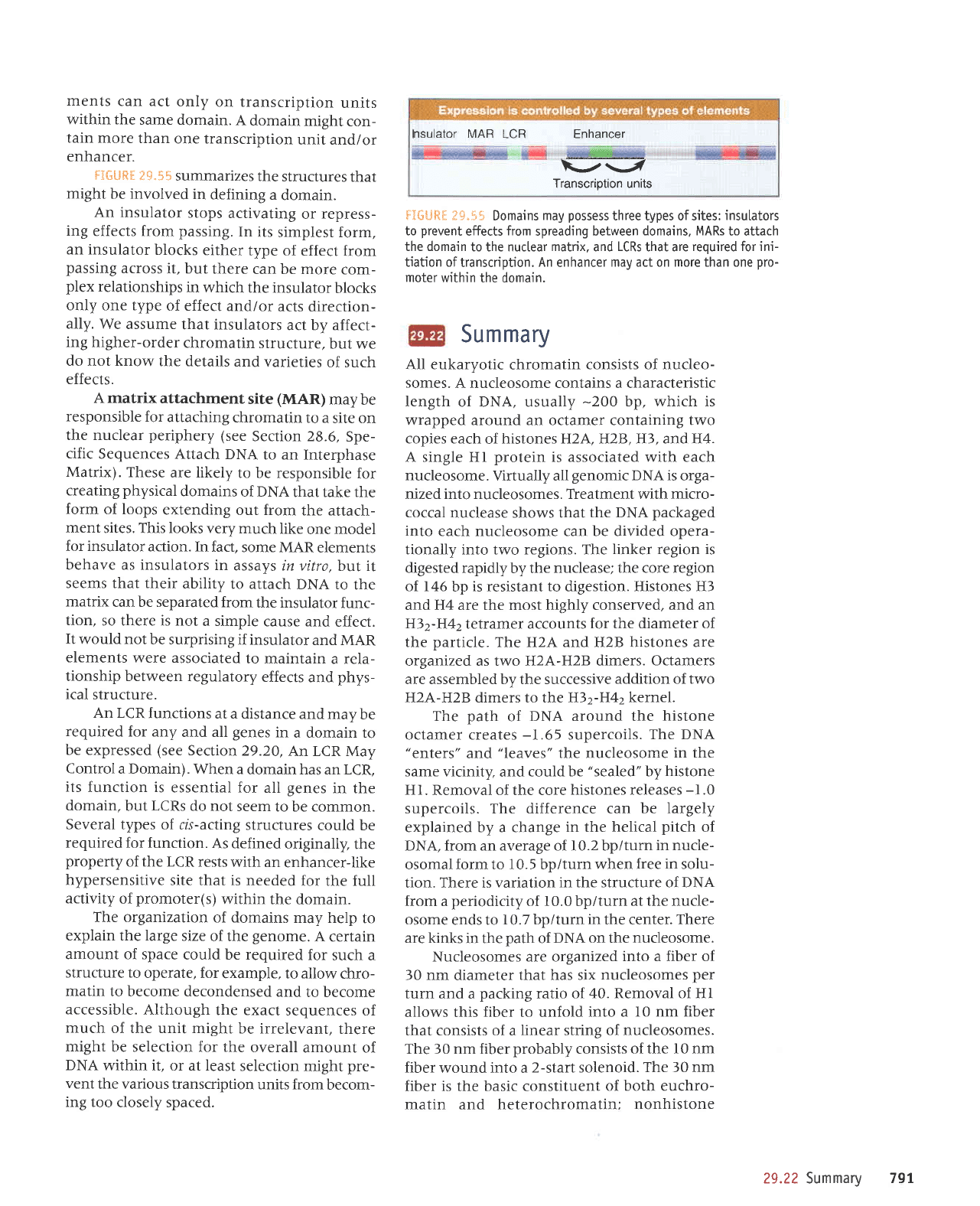

FiGUR[

8S"55

summarizes

the

structures

that

might be involved

in

defining

a

domain.

An insulator

stops

activating

or repress-

ing

effects from passing.

In

its

simplest form,

an insulator

blocks

either

type

of effect

from

passing

across

it, but

there

can be more

com-

plex

relationships

in which

the

insulator

blocks

only one type

of effect

and/or

acts

direction-

ally.

We assume

that insulators

act by affect-

ing higher-order

chromatin

structure,

but we

do not know

the details

and

varieties

of such

effects.

A matrix

attachment

site

(MAR)

may

[re

responsible

for

attaching

chromatin

to a

site on

the nuclear

periphery

(see

Section 28.6,

Spe-

cific

Sequences Attach

DNA

to an

Interphase

Matrix).

These

are likely

to be responsible

for

creating

physical

domains

of DNA

that take the

form

of loops

extending

out from

the attach-

ment

sites. This looks

very much

like

one model

for insulator

action. In

fact,

some MAR

elements

behave as insulators

in

assays invitro,butil

seems that their

ability

to atrach

DNA to

the

matrix

can be separated

from

the insulator

func-

tion,

so there is not

a simple

cause and

effect.

It would not

be surprising

if insulator

and MAR

elements

were associated

to maintain

a rela-

tionship between

regulatory

effects

and

phys-

ical

structure.

An LCR

functions

at a distance

and may

be

required

for any

and all

genes

in

a domain to

be expressed

(see

Section

29.20,

An LCR May

Control

a Domain).

When a

domain has an LCR,

its

function is

essential for

all

genes

in the

domain,

but LCRs do not

seem

to be common.

Several types

of cis-acting

structures

could be

required

for function.

As defined

originally,

the

property

of

the LCR

rests

with an

enhancer-like

hypersensitive

site that

is needed

for the full

activity

of

promoter(s)

within

the domain.

The organization

of domains

may help

to

explain the large

size

of the

genome.

A certain

amount of space

could be required

for

such a

structure to

operate, for

example, to allow

chro-

matin

to become decondensed

and

to beconte

accessible.

Although

the exact

sequences of

much

of the unit

might be irrelevant,

there

might

be selection for the

overall

amount of

DNA

within it, or at least

selection

might

pre-

vent

the various transcription

units from

becom-

ing too

closely spaced.

nsulator MAR

LCR Enhancer

t-r{;7

Transcription units

flGllR*

?*"55 Domains

may

possess

three types of sites:

insulators

to

prevent

effects

from

spreading between

domains, MARs

to attach

the domain

to the nuclear

matrix.

and

LCRs

that are

required for ini-

tiation oftranscription. An

enhancer

may act on more than one

pro-

moter within

the domain.

Summary

All eukaryotic

chromatin

consists of nucleo-

somes.

A nucleosome contains a characteristic

length

of DNA, usually

-200

bp, which is

wrapped around an octamer containing two

copies each

of

histones H2A,H2B, H3, and H4.

A single Hl

protein

is associated with each

nucleosome.

Virtually all

genomic

DNA is

orga-

nized into nucleosomes. Tfeatment with micro-

coccal

nuclease shows that

the DNA

packaged

into

each nucleosome can be divided opera-

tionally into two regions. The

linker region is

digested rapidly

by the

nuclease; the core region

of 146

bp

is

resistant

to

digestion.

Histones H3

and H4 are the most highly conserved,

and an

H32-H42tetramer

accounts

for the diameter of

the

particle.

The H2A and H2B histones are

organized as two H2A-H2B dimers.

Octamers

are assembled by the successive

addition of two

H2A-H2B dimers to the H3z-H42

kernel.

The

path

of

DNA around the histone

octamer creates

-1.65

supercoils.

The DNA

"enters"

and

"leaves"

the nucleosome

in tne

same

vicinity, and could

be

"sealed"

by

histone

Hl.

Removal of the core

histones releases

-L0

supercoils. The difference can

be largely

explained by a change

in the helical

pitch

of

DNA, from an average of 10.2 bp/turn

in nucle-

osomal form to 10.5 bp/turn

when free

in

solu-

tion. There is variation

in the structure of DNA

from a

periodicity

of 10.0 bp/turn

at the nucle-

osome

ends to

10.7 bp/turn in the center.

There

are kinks

in the

path

of

DNA on the

nucleosome.

Nucleosomes

are organized

into a fiber of

30 nm

diameter

that has six

nucleosomes

per

turn and

a

packing

ratio of

40. Removal of Hl

allows this fiber to unfold

into a

l0 nm fiber

that consists of a linear string

of nucleosomes.

The l0 nm fiber

probably

consists

of the l0 nm

fiber

wound into a

2-start solenoid.

The l0 nm

fiber is the

basic

constituent

of both euchro-

matin and heterochromatin;

nonhistone

29.22 Summary

791

proteins

are responsible

for further organiza-

tion

of the

fiber into chromatin or chromosome

ultrastructure.

There are two

pathways

for nucleosome

assembly. In the replication-coupled

pathway,

the

PCNA

processivity

subunit of the

replisome

recruits CAF-1, which

is

a

nucleosome as-

sembly factor. CAF- I assists the deposition

of

H32-H42

tetramers

onto the daughter duplexes

resulting from replication. The tetramers

may

be

produced

either by disruption

of existing

nu-

cleosomes by the replication fork or as the

result

of assembly from newly synthesized

histones.

Similar sources

provide

the H2A-H2B dimers

that then assemble with the

H32-H42tetramer to

complete the nucleosome. The H3z-H4ztetramer

and the H2A-H2B dimers assemble at random,

so the

new nucleosomes may include both

pre-

existing and newly synthesized

histones.

RNA

polymerase

displaces histone octamers

during transcription.

Nucleosomes

reform on

DNA

after the

polymerase

has

passed,

unless

transcription is very intensive

(such

as

in rDNA)

when

they

may

be displaced completely.

The

replication-independent

pathway

for nucleo-

some assembly

is responsible for replacing his-

tone octamers that

have

been displaced

by

transcription. It uses the histone

variant H3.l

instead of Hl. A similar

pathway,

with another

alternative

to

H3, is

used

for

assembling

nu-

cleosomes at centromeric DNA sequences

fol-

lowing replication.

An insulator blocks the transmission of acti-

vating

or

inactivating

effects

in

chromatin.

An

insulator

that

is located

between an enhancer

and a

promoter

prevents

the enhancer from

activating the

promoter.

T\ryo insulators define

the region between them as a regulatory

domain; regulatory interactions within the

domain are limited to it, and the domain is insu-

lated

from outside effects. Most insulators block

regulatory

effects

from

passing

in either direc-

tion, but some are directional. Insulators usu-

ally can block

both

activating

effects

(enhancer-

promoter

interactions) and inactivating effects

(mediated

by spread

of

heterochromatin),

but

some are limited

to one or the other. Insulators

are thought to act via

changing

higher-order

chromatin

structure, but the details are not

certaln.

TWo

tlpes of changes in sensitivity to nucle-

ases

are associated with

gene

activity. Chro-

matin

capable of being transcribed has a

generally

increased sensitivity

to

DNAase I,

reflecting

a change in structure

over

an exten-

sive region that

can be defined as a domain

con-

taining

active or

potentially

active

genes.

Hlper-

sensitive sites

in DNA occur at discrete

locations,

and are

identified by

greatly

increased

sensitiv-

ity to DNAase L

A hypersensitive site consists

of a sequence

of

-200

bp

from

which

nucleo-

somes

are excluded by

the

presence

of other

proteins.

A hypersensitive site

forms

a bound-

ary that

may cause adjacent

nucleosomes

to be

restricted

in

position.

Nucleosome

positioning

may be important

in controlling access of reg-

ulatory

proteins

to DNA.

Hypersensitive sites occur at several types

of regulators.

Those that regulate transcription

include

promoters,

enhancers, and

LCRs.

Other

sites include origins

for replication and cen-

tromeres. A

promoter

or enhancer acts on a sin-

gle gene,

but an

LCR

contains a

group

of

hypersensitive sites

and may regulate a domain

containing several

genes.

References

The Nucleosome Is

the Subunit

of A[[ Chromatin

Reviews

I(ornberg, R.

D.

(1977).

Structure of chromatin.

Annu. Rev. Biochem.

46,9)l-954.

McGhee, J. D., and Felsenfeld, G

(1980).

Nucleo-

some structure.

Annu. Rev. Biochem 49,

ltlS-t156.

Resea rc h

I(ornberg,

R. D.

(1974).

Chromatin structure: a

repeating unit of

histones

and

DNA.

Science

184, 868-87 r.

Richmond, T.

J.,

Finch, J. T., Rushton, B.,

Rhodes, D., and

Klug, A.

(1984).

Structure ot

the

nucleosome

core

particle

at

7 A resolu-

tion. Nature

Jll, 5j2-5)7 .

DNA Is

Coited

in Arravs

of

Nucteosomes

Rese a

rc h

Finch,

J.

T. et al.

.1977).

Structure

of

nucleosome

core

particles

of chromatin . Nature 269,

29-36.

Nucteosomes Have a Common

Structure

R esea

rc h

Shen, X. et al.

(I995).

Linker histones

are not

essential and affect chromatin

condensation

in vitro. Cell 82, 47-56.

792 CHAPTER 29

Nucleosomes

DNA

Structure

Varies

on

the NucteosomaI

Surface

Review

Wang, J.

(1982\.

The

path

of DNA

in

rhe nucleo-

some.

Cell 29, 724-726.

Res ea rc h

Richmond, T.

J. and Davey,

C. A.

(2003).

The

structure

of

DNA

in

the nucleosome

core.

Nature 42j,

145-150.

The Periodicity

of DNA

Changes

on the Nucteosome

Review

Travers,

A. A. and Klug,

A.

(19871.

The

bending

of DNA in

nucleosomes

and

its wider implica-

tions. Philos Trans.

R.

Soc

Lond

B Biol.

Sci.317.

5)7-561.

0rganization

of the Histone

Octamer

Resea rc h

Angelov,

D., Vitolo,

J. M., Mutskov

V., Dimitrov

S.,

and Hayes,

J. J.

(2001

).

Preferential

interac-

tion of the core histone

tail domains

with

Iinker

DNA. Proc

Natl Acad.

Sci.

USA98,

6599-6604.

Arents,

G.,

Burlingame,

R. W.,

Wang, B.-C., Love,

W. E., and Moudrianakis,

E.

N.

(1991).

The

nucleosomal

core histone

octamer

at 3I A res-

olution: a

tripartite

protein

assembly

and a

left-handed

superhelix. Proc

Natl. Acad. Sci

us.4 88,

r0148-10r52.

Luger, I(.

et al.

(1997).

Crystal

structure of

the

nucleosome

core

parricle

at 28 A resolution.

Nature 389,251-260.

The Path

of Nucteosomes

in the

Chromatin Fiber

Review

Felsenfeld,

G.

and

McGhee,

J. D.

(1986).

Srrucrure

of the 30 nm

chromatin

fiber.

Cell

44,

375-]77.

Resea rch

Dorigo, B.,

Schalch, T., I(ulangara,

A.,

Duda, S.,

Schroeder,

R. R., and Richmond,

T.

J.

(2004).

Nucleosome arrays

reveal the

two-start orga-

nization

of the chromatin

fiber.

Science

jO6.

t57 t-l573.

Schalch, T.,

Duda, S.,

Sargent, D. F.,

and Rich-

mond, T. J.

(2005).

X-ray structure

of a

tetranucleosome

and its implications

for

the

chromatin

Libre. Nature 4)6,

lJ8-141.

Reproduction

of Chromatin

Requires

Assembty

of

Nucteosomes

Osley, M. A.

(1991).

The

regulation

of histone

syn-

thesis in

the cell cycle. Annu.

Rev. Biochem

60,

827-86t.

Reviews

Verreault,

A.

(2000).

De novo nucleosome assem-

bly: new

pieces

in an old

puzzle.

Genes Dev. 14,

t4)o-14]8.

Resea rc h

Ahmad,

I(. and Henikoff, S.

(2001).

Centromeres

are specialized replication domains in hete-

rochromatin.

J

Cell

Biol l5 3. l0l-l 10.

Ahmad,

I(.

and

Henikoff,

S.

(2002).

The histone

variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by

replication-independent

nucleosome

assembly. Mol.

Cell

9, ll9l-I200.

Gruss,

C., Wu, J.,

I(oller, T.,

and Sogo, J.

M.

(19931

. Disruption of the

nucleosomes at

the

replication

fork. EMBO J.

12, 453)-4545.

Loppin,

B., Bonnefoy, E., Anselme, C., Laurencon, A.,

I(arr, T. L.,

and Couble,

P.

(2005).

The histone

H3.3

chaperone HIRA

is

essential

for chro-

matin assembly in the male

pronucleus.

Nature 437, lj86-l)90.

Ray-Gallet,

D.,

Quivy,

J. P., Scamps, C.,

Martini,

E. M., Lipinski, M., and Almouzni, G.

(2002).

HIRA is

critical

for a nucleosome assembly

pathway

independent of DNA synthesis. Mol.

Cell9, 109l-1100.

Shibahara,

I(., and Stillman,

B.

(19991.

Replication-dependent marking of DNA by

PCNA facilitates CAF- I

-coupled

inheritance

of

chromatin.

Cell

96, 57 5-585.

Smith, S. and Stillman, B.

(1989).

Purification and

characterization of CAF-I,

a human cell factor

required

lor chromatin assembly

during DNA

replication in vitro. Cell 58,

15-25.

Smith, S. and

Stillman,

B.

(1991).

Stepwise

assem-

bly

of chromatin

during DNA

replication

in

vitro.

EMBO J. lO,

97 1-980.

Tagami, H.,

Ray-Gallet,

D., Almouzni, G., and

Nakatani, Y.

(2004).

Histone Hl.I and Hl.l

complexes mediate nucleosome

assembly

pathways

dependent or

independent of DNA

synthesis.

Cell

ll6, 5l-61.

Yu, L.

and Gorovsky,

M. A.

(1997).

Constitutive

expression, not a

particular primary

sequence,

is

the important feature

of the H3 replacement

variant

Llv2 in Tetrahymena

thermophila. Mol.

Cell. Biol 17, 6]03-6310.

Are Transcribed

Genes

0rganized

in Nucteosomes?

Review

I(ornberg,

R. D. and Lorch,

Y.

(1992).

Chromatin

structure and transcriprion.

Annu. Rev. Cell

Biol 8, 56)-587.

Histone

Octamers

Are

Disptaced

by Transcription

Researc h

Cavalli,

G. and

Thoma, F.

(

1993

)

.

Chromatin

tran-

sitions during activation

and repression of

galactose-regulated genes in

yeast.

EMBO J.

12,460)46r).

References 793

@

Reviews

Studitsky,

V.

M., Clark, D. J., and

Felsenfeld, G.

(1994).

A histone octamer can step around

a

transcribing

polymerase

without

leaving the

remolare. cell

7 6. 37 l-382.

@

Nucleosome Disp[acement and

Reassembty Require SpeciaI

Factors

Resea rc h

Belotserkovskaya, R., Oh, S., Bondarenko, V.

A.,

Orphanides, G., Studitsky,

V. M., and Rein-

berg, D.

(2001).

FACT

facilitates

transcription-

dependent nucleosome alteration. Science 3Ol,

1090-1093.

Saunders, A., Werner, J., Andrulis, E. D.,

Nakayama,

T., Hirose, S., Reinberg, D., and

Lis,

J.

T

(2003).

Tracking FACT and the RNA

polymerase

II

elongation complex through

chromatin in vivo. Science )Ol,

1094-1096.

Insulators Btock the

Actions

of

Enhancers

and

Heterochromatin

Gerasimova, T. I. and Corces, V. G.

(2001).

Chro-

matin insulators and boundaries: effects on

tra

nscription

and

nu

clear or

ganizalion.

An n u.

Rev.

Genet. 35,

19)-208.

West, A.

G., Gaszner,

M.,

and

Felsenfeld,

G.

(20021.

Insulators:

many functions, many

mechanisms. Genes Dev. 16. 27 l-288.

?W

Insulators

Can

Define

a

Domain

Resea

rc

h

Chung, J. H., Whiteley, M., and Felsenfeld, G.

(19%l

. A 5' element of the chicken

p-globin

domain serves as an insulator in human ery-

throid

cells and

protects

against

position

effect

rn Drosophila

Cell

7 4,

505-514.

Cuvier,

O.,

Hart,

C.

M.,

and

Laemmli,

U.

K.

(1998).

Identification of a class of chromatin bound-

ary elements. Mol.

Cell

Biol 18,7478-7486.

Gaszner, M.,Yazquez,

J.,

and

Schedl,

P.

(1999).

The Zw5

protein,

a component of the scs

chromatin domain boundary, is able to block

enhancer-promoter interaction.

Genes

Dev. l),

2098-2107.

I(ellum,

R. and Schedl, P.

(

I 991

)

. A

position-effect

assay for

boundaries of

higher

order chromo-

somal

domains. Cell 64,941-950.

Pikaart,

M. J., Recillas

-Targa,

F., and Felsenfeld, G.

(

I 998

)

. Loss of transcriptional

activity of a

transgene is accompanied

by

DNA methyla-

tion and histone deacetylation and is

pre-

vented by insulators. Genes Dev. 12,

2852-2862.

Zhao,I(, Hart,

C.

M.,

and

Laemmli,

U. K.

(1995).

Visualization

of chromosomal domains with

boundary element-associated

factor BEAF-12.

Cell 81, 879-889.

Insutators

May Act in One Direction

Resea

rc h

Gerasimova,

T. I., Byrd, I(., and Corces, V. G.

(2000).

A chromatin

insulator determines the

nuclear localization

of DNA. Mol. Cell 6,

r025-to)5.

Harrison, D. A., Gdula,

D. A., Cyne, R. S., and

Corces,

V.

G.

(1993).

A leucine zipper domain

of the suppressor

of hairy-wing

protein

medi-

ates

its repressive effect

on enhancer function.

Genes

Dev. 7, 1966-197 8.

Roseman,

R. R., Pirlotta, V., and Geyer,

P. K.

(19931.

The su(Hw)

protein

insulates

expres-

sion of the

D melanogaster

white

gene

from

chromosomal

position-effecrs.

EMB) J. 12,

435-442.

Insulators Can

Vary in Strength

Resea

rch

Hagstrom,

I(., Muller, M., and Schedl, P.

(1996).

Fab-7 functions as a chromatin domain

boundary

to ensure

proper

segment speci{ica-

tion by the

Drosophila bithorax complex. Genes

Dev.

10,3202-)215.

Mihaly, J. et al.

\1997).

In situ drssection of the

Fab-7 region of the bithorax complex

into a

chromatin domain boundary and a

polycomb-

response element. Development 124,

l

809-l 820.

Zhou, J. and

Levine, M.

(1999).

A novel czi-

regulatory element, the PTS, mediates an anti-

insulator activity inthe Drosophila embryo.

Cell99,567-575.

DNAase Hypersensitive Sites Reflect

Changes

in

Chromatin

Structure

Review

Gross,

D. S. and Garrard, W T.

(1988).

Nuclease

hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu Rev.

Biochem. 57, 159-197.

Resea

rch

Groudine, M., and Weintraub, H.

(1982).

Propaga-

tion of

globin

DNAase I-hypersensitive

sites

in

absence of

factors required for induction:

a

possible

mechanism for

determination. Cell

30, t3t-t39.

Moyne, G., Harper,

F.,

Saragosti, S., and Yaniv M.

(

I 982

).

Absence of

nucleosomes

in a histone-

containing nucleoprotein complex obtained

by dissociation of

purified

SV40

virions.

Cel/

30,

r23-r30.

Scott, W.

A.

and Wigmore,

D.

J.

(1978).

Sites in

SV40 chromatin which are

preferentially

cleaved by endonucleases.

Cell

15,

l5l l-1518.

Varshavsky, A. J., Sundin, O., and Bohn, M.

J.

(1978).

SV40

viral minichromosome:

prefer-

ential exposure of the origin of replication as

probed

by restriction

endonucleases. Nucleic

Acids Res.

5, )469-)479.

794 CHAPTER 29 Nucteosomes

Domains

Define

Regions

That

Contain

Active

Genes

Research

Stalder, J. et

al.

(1980).

Tissue-specific

DNA

cleav-

age in

the

globin

chromatin

domain

intro-

duced

by DNAase

I.

Cell 20, 45t-460.

An LCR

May

Control

a Domain

Reviews

Bulger,

M. and

Groudine,

M.

(1999).

Looping

ver-

sus

linking:

toward a

model for

long-distance

gene

activation.

Genes Dev. Lj^,2465-2477.

Grosveld, F., Antoniou,

M., Berry,

M., De Boer,

E.,

Dillon,

N., Ellis,

J., Fraser, P.,

Hanscombe,

O..

Hurst,

J., and Imam,

A.

(1993).

The regulation

of human

globin gene

switching.

Philos. Trans.

R. Soc Lond.

B Biol.

Sci. )39, t8)-t9t.

Research

Gribnau,

J., de

Boer, E., Tfimborn, T.,

Wijgerde,

M.,

Milot, E.,

Grosveld, F., and

Fraser,

P.

(I998).

Chromatin interaction mechanism of tran-

scriptional

control in vitro. EMBO J. 17,

6020-6027.

Spilianakis,

C. G.,

Lalioti, M. D., Town, T., Lee,

G. R.,

and

Flavell, R. A.

(2005).

Interchromo-

somal

associations between alternatively

expressed loci.

Nature

475, 637

-645.

van Assendelft,

G. B., Hanscombe, O., Grosveld,

F.,

and

Greaves, D.

R.

(I989).

The

B-globin

domi-

nant

control region activates

homologous

and

heterologous

promoters

in

a tissue-specific

manner.

Cell 56, 969-977.

What

Constitutes a

Regulatory Domain?

Review

West, A. G., Gaszner, M., and Felsenfeld, G.

(2OO2l

.Insulators: many functions/

many

mechanisms.

Genes

Dev. 16, 27 1-288.

References 795

Controlting

Chromatin

Structure

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Introduction

Chromatin Can

Have

Atternative States

.

Chromatin structure is stable and

cannot

be changed by

altering

the equitibrium of transcription factors and

histones.

Chromatin Remodeting Is an Active Process

r

There are several

chromatin

remodeling

complexes that use

energy

provided

by

hydrotysis

of

ATP.

r

The SWI/SNF, RSC.

and

NURF

comptexes atl are

very

large,

and they share some

common subunits.

.

A remodeling

comptex does not

itself

have specificity

for

any

particular

target site, but must be recruited by a compo-

nent

of the transcription apparatus.

Nucteosome

0rganization

May Be

Changed

at the Promoter

o

Remodeting

comptexes are recrujted to

promoters

by

sequence-specjfi

c activators.

r

The factor

may be released

once the

remodeting

complex

has

bound.

r

The MMTV

promoter

requires

a change

in rotational

position-

ing of a nucteosome

to a[[ow an activator

to

bind to DNA on

the nucteosome.

Histone

Modification Is

a

Key

Event

r

Histones

are modified

by

methylation,

acetylation, and

phosphory[ation.

Histone

Acetytation

0ccurs in Two

Circumstances

o

Histone

acetytation

occurs transjentlyat replication.

o

Histone

acetylation

is associated with activation of

gene

expresslon.

Acetytases

Are Associated

with Activators

r

Deacetytated

chromatin may have

a more condensed

structu

re.

r

Transcription

activators

are associated with histone acety-

lase

activities in [arge

complexes.

o

Histone

acetylases

vary in their

target specificity.

o

Acetylation

coutd

affect transcription in a

quantitative

or

quatitative

wa;.

Deacetylases

Are Associated with Repressors

o

Deacetytation is associated with

repression

of

gene

activity.

r

Deacetylases are

present

in comptexes with

repressor

activity.

Methytation

of

Histones and

DNA Is

Connected

.

Methytation of both

DNA

and

histones is a feature of inac-

tive

chromatin.

o

The

two types

of methytation event

may

be connected.

Chromatin States

Are Interconverted by Modification

o

Acetytation of histones is associated

with

gene

activation.

.

Methylation of

DNA

and of

histones is associated with

heteroch ro mati n.

Promoter Activation

Involves

an 0rdered Series of

Events

.

The remodeting comptex

may recruit

the acetytating

complex.

.

Acetytation of histones

may

be the event that

maintains

the

complex

jn

the actjvated state.

Histo ne Phosphorylation

Affects

Ch

romati n

Structure

o

At

least two

histones are targets

for

phosphorylation, possi-

bty with opposing effects.

Some Common

Motifs Are Found in Proteins That Modifv

Chromatin

.

The chromo domain is

found in

several chromatin oroteins

that have ejther activating or

repressing

effects on

gene

expressron.

.

The SET domain is

part

of the catatytic site of

protein

methyttra nsferases.

.

The bromo domain

is found in

a

variety

of

proteins

that

interact with chromatin and

is

used to

recognize

acetylated

sites on histones.

Summary

796

Introduction

When

transcription is

treated in

terms

of

inter-

actions involving

DNA and

individual

transcrip-

tion factors

and RNA

polymerases,

we

get

an

accurate description

of the

events that

occur ilt

vitro,but this lacks

an important

feature

of tran-

scription in vivo.

The cellular

genome

is or-

ganized

as nucleosomes,

but initiation

of

transcription

generally

is

prevented

if the

pro-

moter region is

packaged

into

nucleosomes.

In

this sense, histones function

as

generalized

repressors

of transcription

(a

rather

old idea),

although

we see in this

chapter that

they are

also involved

in more

specific interactions.

Acti-

vation of a

gene

requires

changes

in the state

of

chromatin: The

essential issue

is how

the tran-

scription factors

gain

access to the

promoter

DNA.

Local

chromatin

structure is an integral

part

o{ controlling

gene

expression.

Genes may exist

in either

of two structural

conditions. Genes

are

found in

an

"active"

state only in

the cells in

which they

are expressed. The

change of struc-

ture

precedes

the act

of transcription,

and indi-

cates that the

gene

is

"transcribable."

This

suggests that acquisition

of the

"active"

struc-

ture must be the first

step in

gene

expression.

Active

genes

are

found

in

domains of euchro-

matin

with a

preferential

susceptibility

to

nucle-

ases

(see

Section

29.l9,Domains

Define Regions

That

Contain Active

Genes). Hypersensitive

sites

are created at

promoters

before

a

gene

is acti-

vated

(see

Section 29.I8, DNAase

Hypersensi-

tive Sites Change

Chromatin Structure).

More recently

it has turned

out that there

is an intimate and

continuing

connection

between initiation

of transcription

and chro-

matin

structure. Some

activators of

gene

tran-

scription directly modify

histones; in

particular,

acetylation

of

histones

is associated

with

gene

activation. Conversely,

some repressors

of

tran-

scription function

by deacetylating

histones.

Thus

a reversible change in

histone structure

in

the vicinity of the

promoter

is involved in

the control

of

gene

expression.

This

may

be

part

of the mechanism by

which a

gene

is main-

tained in

an

active or inactive state.

The mechanisms by which local

regions of

chromatin

are maintained

in an inactive

(silent)

state are related to the means

by which an indi-

vidual

promoter

is repressed. The

proteins

involved

in the formation of

heterochromatin

act on

chromatin

via the histones,

and modifi-

cations of the

histones may be an

important

feature in the interaction.

Once established,

such changes in chromatin

may

persist

through

cell

divisions, creating

an epigenetic

state in

which the

properties

of

a

gene

are determined

by the self-perpetuating structure

of chromatin.

The name

epigenetic

reflects the

fact that a

gene

may have

an

inherited condition

(it

may be

active or may be inactive)

that does

not

depend

on

its

sequence.

Yet a further

insight into epi-

genetic properties

is

given

by the self-perpetu-

ating

structures

of

prions

(proteinaceous

infectious

agents).

Chromatin

Can

Have

Alternative

States

.

Chromatin

structure

is stable

and cannot be

changed by

altering the equitibrium

of

transcription

factors and

histones.

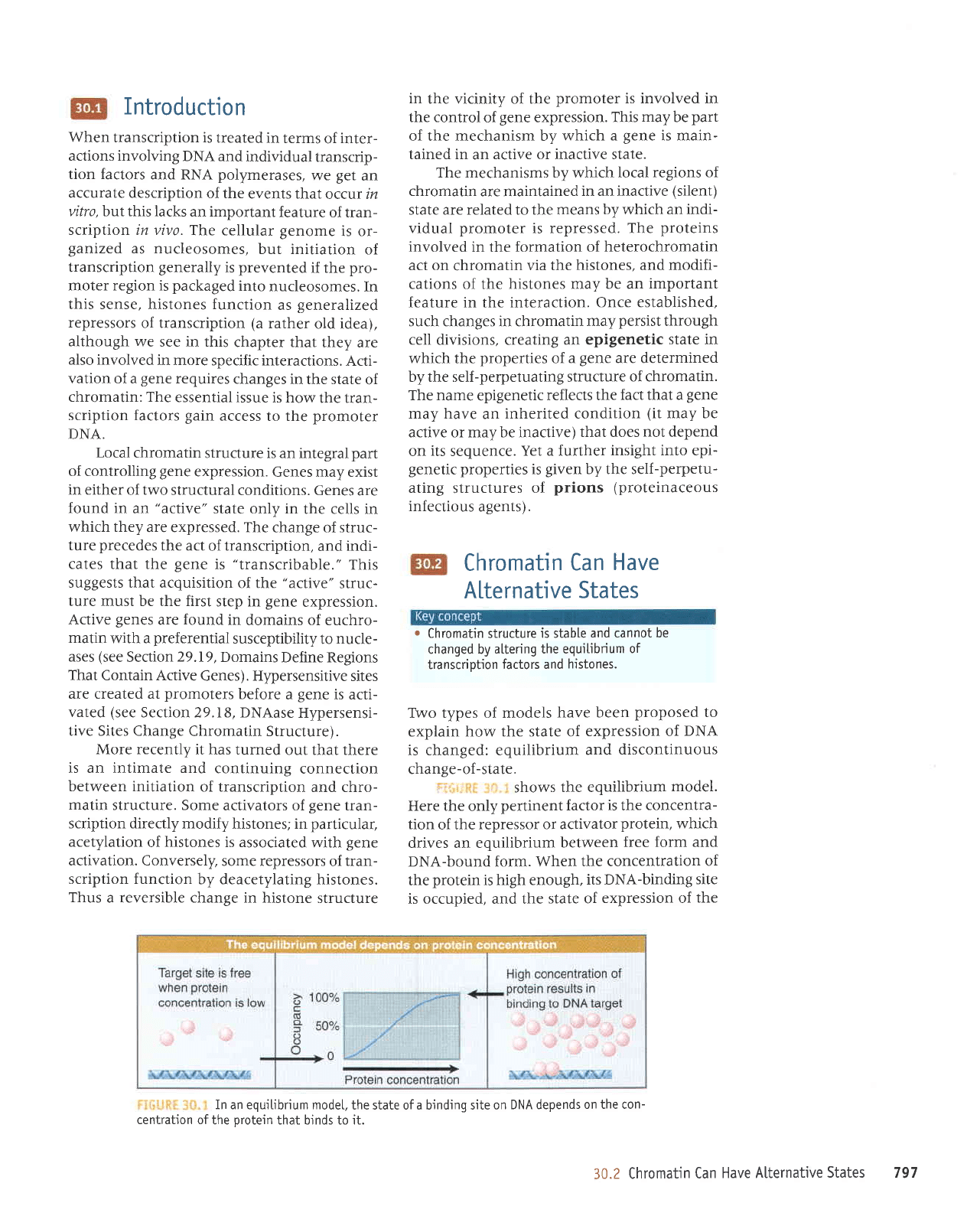

Two types of models

have been

proposed

to

explain

how the state of

expression of

DNA

is changed: equilibrium

and

discontinuous

change-of-state.

',r

.,

shows

the equilibrium

model.

Here the

only

pertinent factor

is

the

concentra-

tion

of the

repressor or activator

protein,

which

drives an equilibrium

between

free

form and

DNA-bound form. When

the concentration

of

the

protein

is high enough,

its DNA-binding

site

is occupied, and the

state of

expression of

the

In an equitibrium model.

the state ofa binding site on

DNA depends

on the con-

centratjon of

the

protein

that bjnds to it.

30.2

Chromatin

Can

Have Alternative

States

797

DNA

is affected.

(Binding

might either repress

or activate any

particular

target sequence.) This

type of model explains the regulation

of

tran-

scription in bacterial cells, where

gene

expres-

sion is determined exclusively by the actions of

individual repressor and

activator

proteins (see

Chapter I2, The

Operon). Whether a bacterial

gene

is

transcribed can be

predicted

from the

sum of the

concentrations of the

various

fac-

tors that either activate or repress the individ-

ual

gene.

Changes in these

concentrations a/

any time will

change the state of expression

accordingly.

In most cases, the

protein

binding

is

cooperative, so that once

the concentration

becomes high

enough, there is a rapid associa-

tion with DNA, resulting in

a switch

in

gene

expressron.

A

different situation applies with eukary-

otic

chromatin. Early in vitro

experiments

showed that either an

active or

inactive

state

can

be established, but this is not

affected by

the subsequent addition

of other components.

The transcription

factor TFnyA,

which

is required

for RNA

polymerase

III to transcribe 5S rRNA

genes,

cannot activate its target

genes

in

vitro

if,

they are complexed

with

histones.

If the factor

is

presented

with free DNA, though, it forms

a

transcription complex,

and then the addition

of histones

does

not

prevent

the

gene

from

remaining

active.

Once the factor has

bound,

it remains

at the site;

this allows

a succession of

RNA

polymerase

molecules to initiate transcrip-

tion. Whether the

factor

or

histones

get

to the

control site first may be the critical factor.

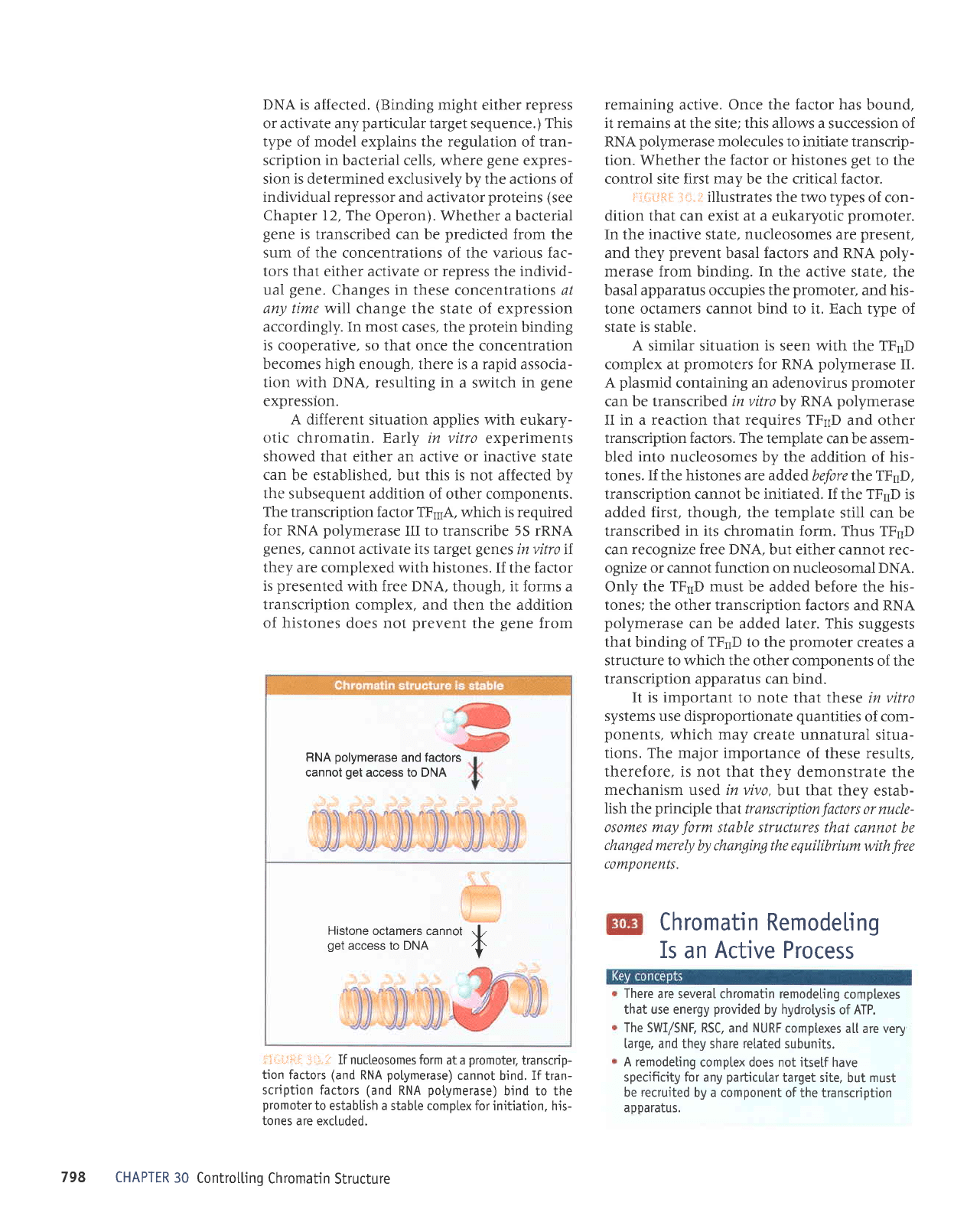

l:*{.!ft1, .l,J.J

illustrates the two types

of con-

dition that can exist

at a

eukaryotic

promoter.

In the inactive state, nucleosomes are

present,

and they

prevent

basal

factors

and RNA

poly-

merase from binding. In the active

state. the

basal apparatus occupies

the

promoter,

and his-

tone octamers cannot bind to it. Each tvne of

state is stable.

A

similar situation

is seen

with the TF1D

complex at

promoters

for RNA

polymerase

II.

A

plasmid

containing an adenovirus

promoter

can be transcribed in vitro by RNA

polymerase

II in a reaction that requires TF11D

and other

transcription factors. The

template can be assem-

bled

into

nucleosomes by the addition

of

his-

tones. If

the

histones are added

before tl:'eTF1D,

transcription cannot be initiated. If

the

TF1D

is

added first, though, the

template still can be

transcribed

in its

chromatin form. Thus TF11D

can recognize free DNA, but either

cannot

rec-

ognize or cannot function on nucleosomal

DNA.

Only the TFnD must be added before

the his-

tones; the other transcription factors

and RNA

polymerase

can be added

later.

This suggests

that

binding of

TFnD

to the

promoter

creates

a

structure to which the other components

of the

transcription apparatus can bind.

It is important

to note that these

in

vitro

systems use disproportionate

quantities

of com-

ponents,

which

may

create unnatural

situa-

tions. The major importance

of these results,

therefore, is not that they

demonstrate the

mechanism used iz vivo,bul

that they

estab-

lish

the

principle

Lhat transcription

factors

or nucle-

osomes may

form

stable structures

that cannot be

ch

ang e d mer e ly by ch ang ing the e

q

ui lib rium

with

fr

e e

cjmpjnents.

Chromatin RemodeLing

Is

an

Active Process

There

are several chromatin remodeling

complexes

that use energy

provided

by

hydrotysis

of ATP.

The SWI/SNF,

RSC, and

NURF

comptexes

a[[ are very

[arge, and

they share retated subunits.

A remodeling

comptex does not itsetf have

specificity for any

particutar

target site,

but

must

be

recruited

by a component

of the transcription

appararus.

RNA

polymerase

and factors

cannot

get

access to DNA

Histone

octamers cannot

,f,

get

access to DNA

0

,r!i:.iiitii

Jil..i

If nucteosomes form

at a

promoter.

transcrip-

tion factors

(and

RNA

potymerase)

cannot

bind.

If

tran-

;cription factors (and

RNA

potymerase)

bind to the

promoter

to establish a stabte

comptex for initiation, his-

tones are excluded.

CHAPTER

30

Controtting

Chromatin

Structure

798

The

general process

of inducing

changes in chro-

matin structure is

called chromatin

remod-

eling. This consists

of mechanisms

for displacing

histones

that depend

on the input

of energy.

Many

protein-protein

and

protein-DNA

con-

tacts need

to be disrupted

to release histones

from chromatin. There

is no free

ride: The

energy must be

provided

to disrupt

these con-

tacts.

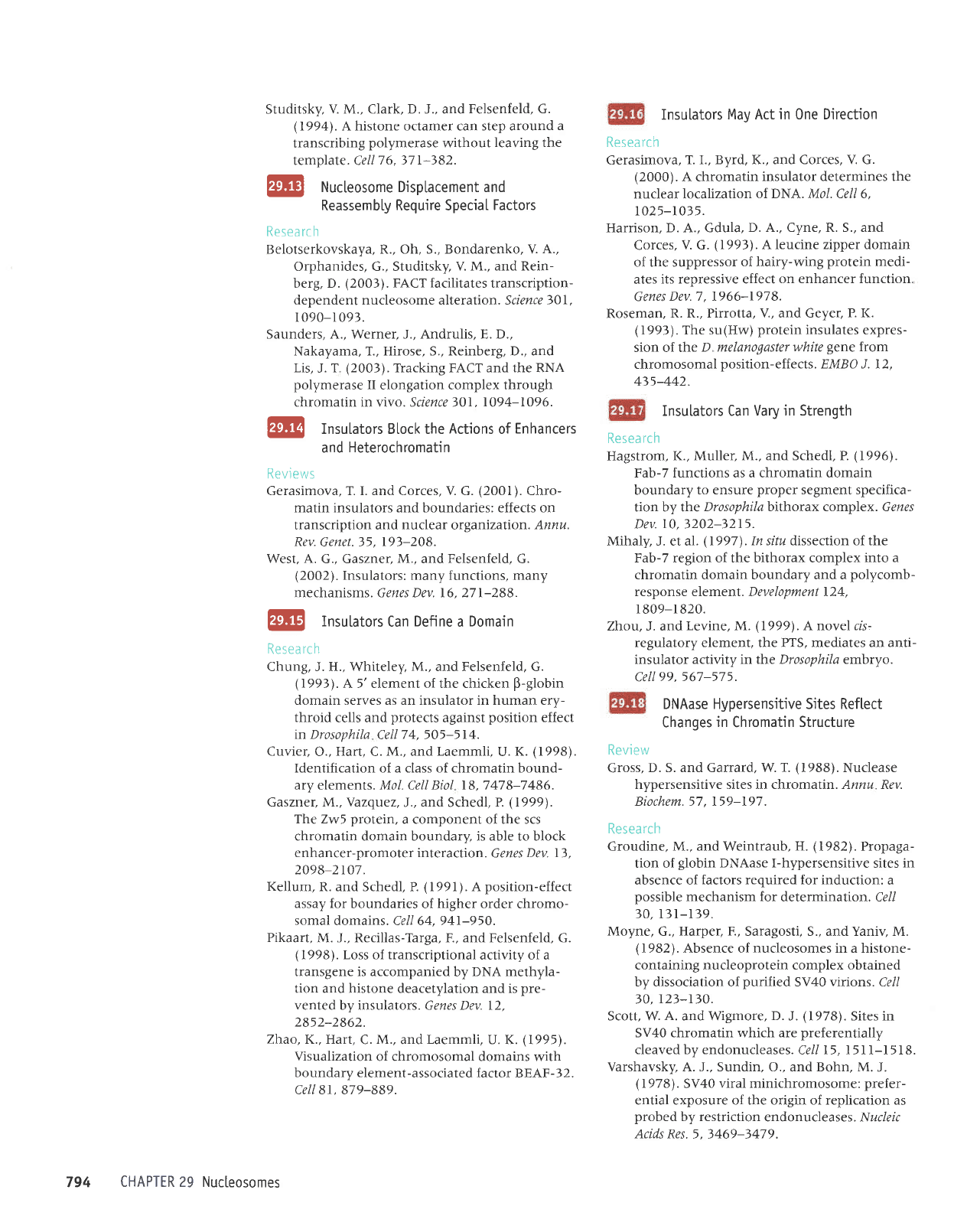

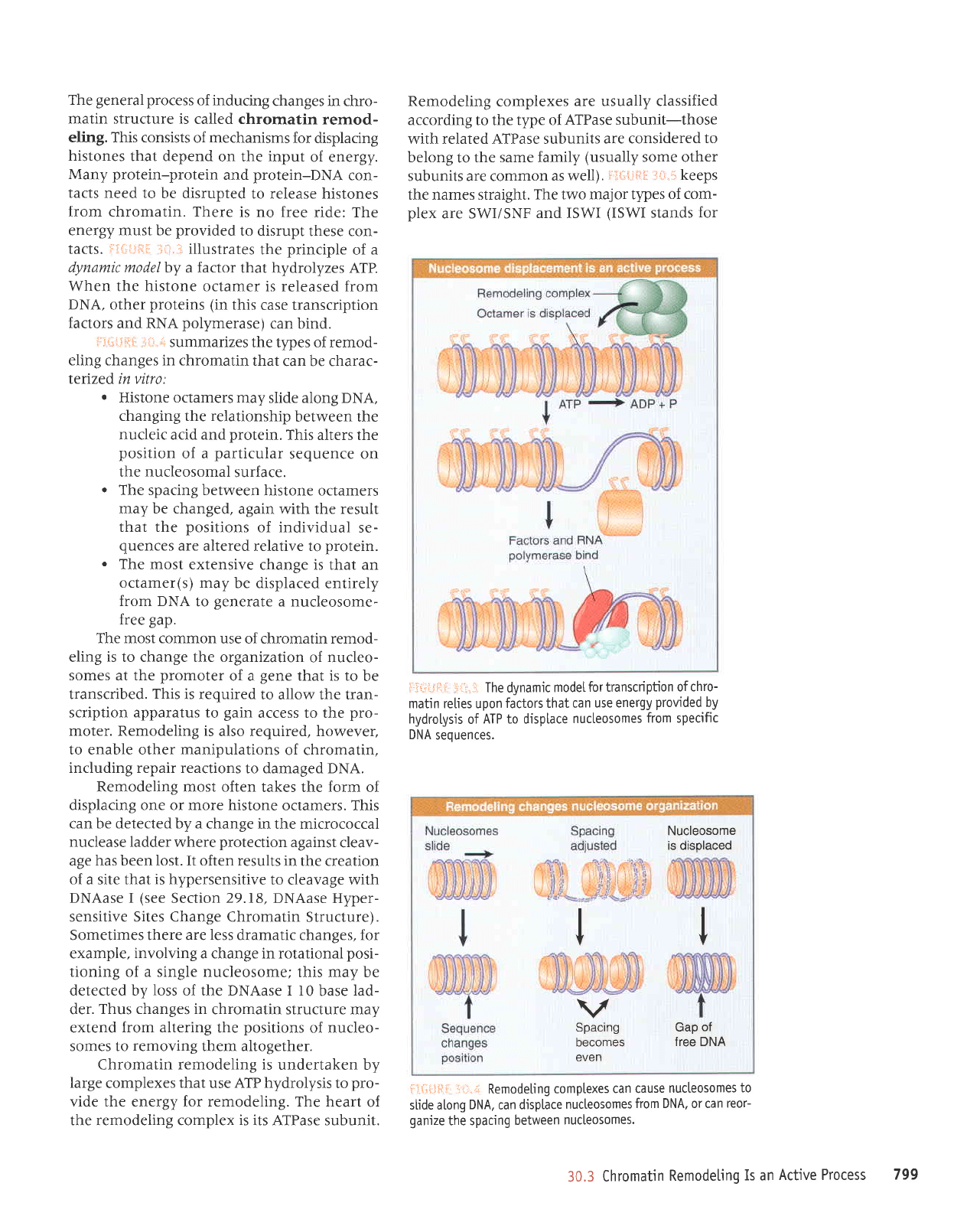

fii-:i":{il

.:!{.i,::l

illustrates

the

principle

of

a

dynamic

model by a factor

that hydrolyzes ATP.

When the histone

octamer is released from

DNA,

other

proteins (in

this

case transcription

factors

and RNA

polymerase)

can bind.

i"5i;i,Ji'ti

.:1,.ii..:.'

51m-".izes

the types of remod-

eling changes in chromatin

that

can be charac-

terized

in

vitro:

.

Histone octamers

may slide along DNA,

changing the relationship

between the

nucleic acid and

protein.

This alters the

position

of a

particular

sequence on

the nucleosomal

surface.

.

The spacing between

histone octamers

may be changed,

again with the result

that the

positions

of individual

se-

quences

are

altered relative to

protein.

.

The most extensive

change is that an

octamer(s) may

be displaced

entirely

from DNA

to

senerate

a nucleosome-

free

gap.

The most common

use of chromatin remod-

eling

is

to change the organization

of nucleo-

somes at the

promoter

of a

gene

that is to

be

transcribed.

This

is required

to allow the tran-

scription apparatus to

gain

access to the

pro-

moter. Remodeling is

also required, however,

to enable other manipulations

of chromatin,

including repair reactions

to damaged DNA.

Remodeling most often

takes the

form

of

displacing one or more histone

octamers. This

can be detected by a

change in the micrococcal

nuclease ladder

where

protection

against

cleav-

age has been lost. It often results

in the creation

of a site that

is

hypersensitive

to cleavage with

DNAase I

(see

Section

29.I8,

DNAase Hyper-

sensitive Sites Change Chromatin

Structure).

Sometimes there are

less

dramatic changes, for

example,

involving

a change in rotational

posi-

tioning of a single nucleosome;

this may be

detected by

loss

of the DNAase I I0

base

lad-

der.

Thus changes in

chromatin structure may

extend

from altering

the

positions

of nucleo-

somes to

removing

them altogether.

Chromatin

remodeling is

undertaken by

large

complexes

that

use

ATP

hydrolysis to

pro-

vide the energy for remodeling. The heart

of

the remodeling complex

is

its ATPase subunit.

Remodeling

complexes

are usually classified

according

to the

type of ATPase

subunit-those

with related ATPase subunits

are considered

to

belong

to

the same family

(usually

some other

subunits are common

as well).

| lillii]$

::l+.ii

keeps

the names straight.

The two major tlpes

of com-

plex

are SWI/SNF

and ISWI

(ISWI

stands

for

ii{.:i.:iii

:ii.'!.-i The dynamic

model

for transcription

of chro-

matin reties upon

factors that can

use energy

provided

by

hydrotysis

of

ATP to disp[ace

nucteosomes

from specific

DNA

seouences.

+'iiltJitF

:!Li.+ Remodeling

comptexes

can cause

nucleosomes

to

slide along

DNA,

can

displace

nucleosomes

from DNA. or can

reor-

ganize

the spacing

between

nucleosomes.

Nucleosome

is displaced

i

I

T

I

v

Gap

of

free DNA

,r.

r

,i,'\

'i

!l

rl.;

I

I

v

V

Spacing

becomes

30.3

Chromatin

Remodelinq

Is an

Active Process

799

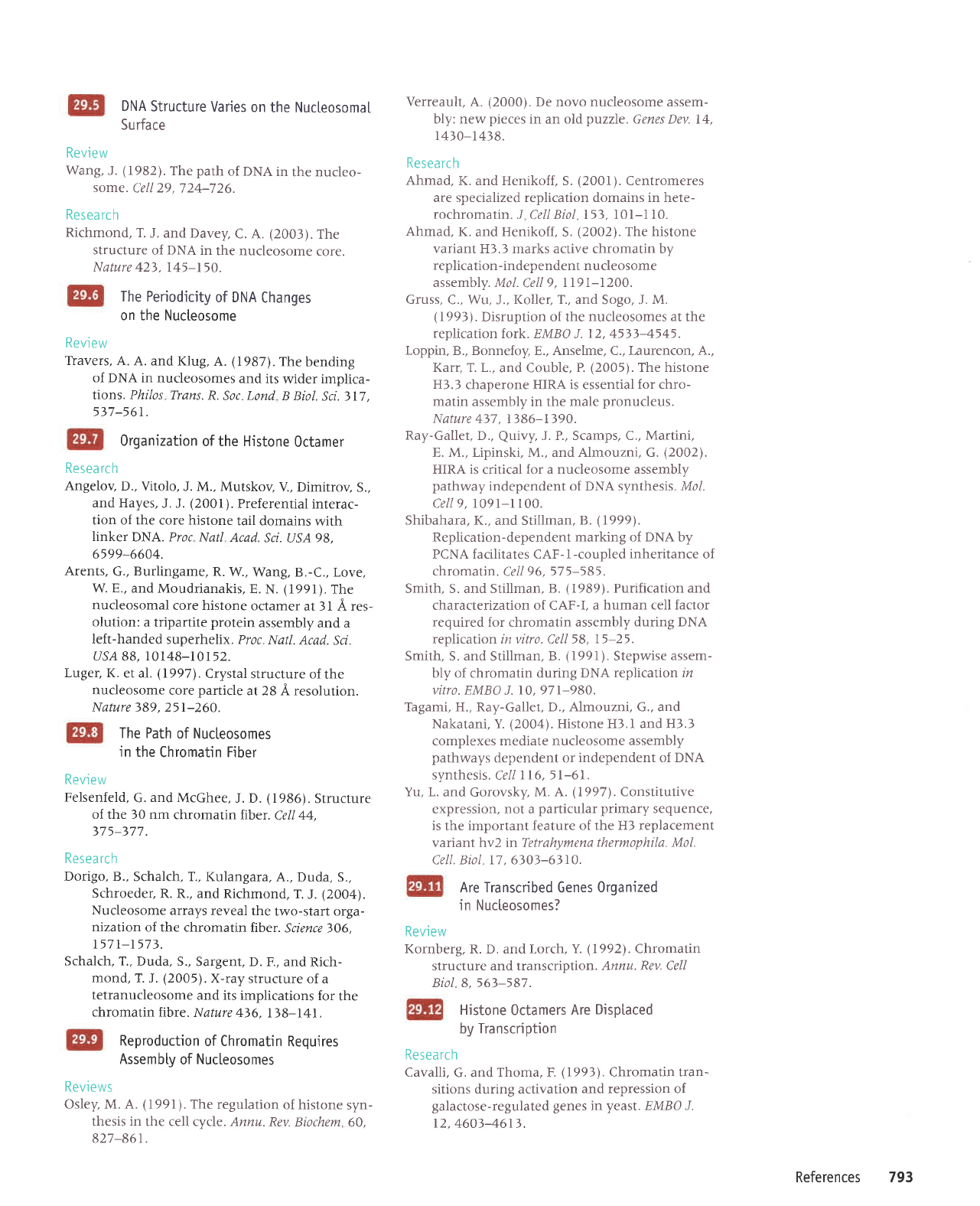

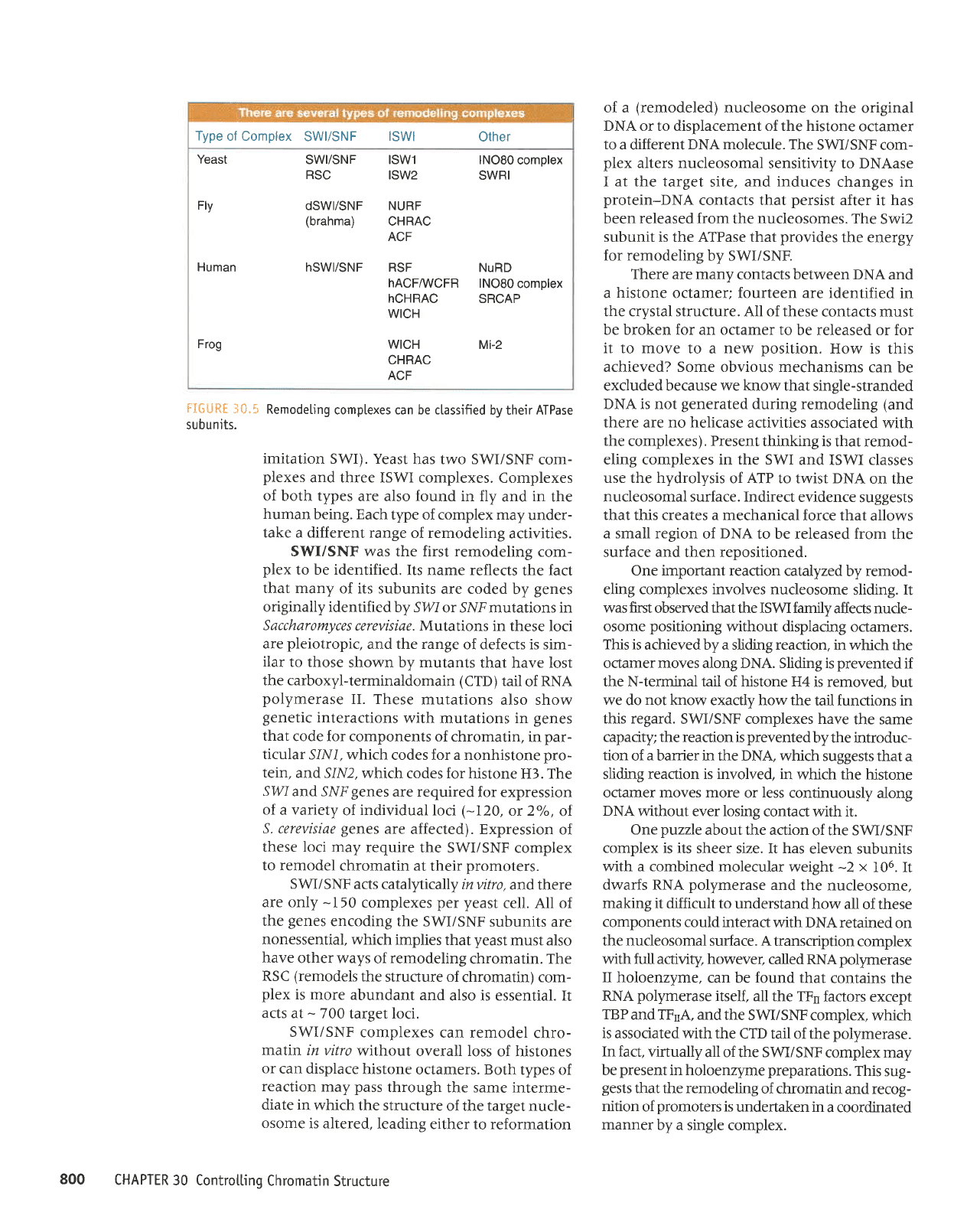

Type

of Complex

SWI/SNF

lSWl

Other

Yeast

SWYSNF lSWl lNO80

complex

RSC

ISW2

SWRI

Fly

dSW|/SNF NURF

(brahma)

CHRAC

ACF

Human

hSW|/SNF RSF

NuRD

hACFAIVCFR

lNO80

complex

hCHRAC

SRCAP

WICH

Frog

WICH

Mi-2

CHRAC

ACF

tIGiJRE

ii0.5

subunits.

Remodeling

complexes can be classified

by their ATPase

imitation

SWI). Yeast

has two SWI/SNF

com-

plexes

and three ISWI

complexes. Complexes

of both types

are also

found

in fly

and

in

the

human

being. Each

type of complex may

under-

take a different range

of remodeling

activities.

SWI/SNF

was

the first remodeling

com-

plex

to be identified.

Its name reflects

the

fact

that many

of its subunits

are coded

by

genes

originally identified

by SWI

or SNF mutations in

Saccharomyces

cerevisiae. Mutations

in these loci

are

pleiotropic,

and the range

of defects is sim-

ilar

to those

shown by mutants

that have lost

the carboxyl-terminaldomain (CTD)

tail

of

RNA

polymerase

II. These

mutations

also show

genetic

interactions

with mutations in

genes

that

code for components

of chromatin,

in

par-

ticular

SINI, which

codes for a nonhistone

pro-

tein,

and SIN2,

which codes for

histone H3. The

SI4'1

and SNF

genes

are required

for expression

of

a variety

of

individual

loci

(-120,

or 2"h,

of.

S. cerevisiae

genes

are

affected). Expression

of

these loci

may require

the SWI/SNF

complex

to remodel

chromatin at

their

promoters.

SWI/SNF

acts catalytically

invitro,

and there

are only

-150

complexes

per

yeast

cell. All of

the

genes

encoding the

SWI/SNF

subunits are

nonessential, which

implies

that

yeast

must aiso

have

other ways

of

remodeling

chromatin. The

RSC

(remodels

the

structure of

chromatin) com-

plex

is

more abundant

and

also is essential. It

acts

at

-

700

target loci.

SWI/SNF

complexes

can remodel

chro-

matin

in vitro

without

overall loss

of histones

or

can displace

histone

octamers. Both

types of

reaction

may

pass

through

the same interme-

diate in

which

the structure

of the target nucie-

osome

is altered,

leading

either to reformation

of a

(remodeled)

nucleosome

on the original

DNA or to displacement of the histone

octamer

to

a different

DNA molecule.

The S\M/SNF

com-

plex

alters nucleosomal

sensitivity to DNAase

I at the target

site, and

induces

changes in

protein-DNA

contacts that

persist

after it

has

been

released

from the nucleosomes. The

Swi2

subunit is the ATPase that

provides

the energy

for remodeling

by SWI/SNF.

There are many

contacts between DNA

and

a histone octamer; fourteen are identified

in

the crystal structure. All of these

contacts must

be broken for an octamer to

be released or for

it to move

to a

new

position.

How is

this

achieved? Some obvious mechanisms

can

be

excluded because we know that

single-stranded

DNA is not

generated

during remodeling (and

there

are

no helicase

activities associated

with

the

complexes). Present thinking is

that remod-

eling complexes in the SWI

and ISWI classes

use the hydrolysis

of ATP to twist DNA

on the

nucleosomal surface. Indirect

evidence

suggests

that this creates a mechanical

force that

allows

a small region

of

DNA

to be released from

the

surface and then repositioned.

One important reaction

catalyzed

by

remod-

eling complexes involves nucleosome

sliding.

It

was first

observed that the IS\M family

affects nude-

osome

positioning

without

displacing octamers.

This is

achieved by a sliding reaction, in which

the

octamer moves along DNA. Sliding

is

prevented

if

the N-terminal tail of histone

H4 is removed,

but

we do

not

know exactly how the

tail functions in

this regard.

SWI/SNF complexes have

the same

capacity; the reaction

is

prevented

by the introduc-

tion

of

a

barrier

in

the DNA" which

suggests that

a

sliding reaction is involved, in

which the

histone

octamer moves more

or

less

continuously

along

DNA

without ever losing

contact with it.

One

puzzle

about the action

of the S\M/SNF

complex is its

sheer size. It has

eleven subunits

with a combined molecular

weight

-2

x

106. It

dwarfs RNA

polymerase

and

the nucleosome,

making

it difficult to

understand how

all of these

components could interact

with DNA retained

on

the nucleosomal

surface. A transcription

complex

with

full

activity, howeve(,

called RNA

polymerase

II

holoenzyme,

can be found that

contains

the

RNA

polymerase

itself, all the TFn

factors

except

TBP

and TFnA, and

the S\M/SNF

complex,

which

is

associated with the

CTD tail of the

polymerase.

In

fact, virtually

all of the S\M/SNF

complex

may

be

present

in holoenzyrne

preparations.

This

sug-

gests

*rat the remodeling

of chromatin

and recog-

nition

of

promoters

is

undertaken in

a coordinated

manner

by a

single complex.

800

CHAPTER

30 Controtting

Chromatin

Structure