Layman D. Biology Demystified: A Self-Teaching Guide

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

As a result of this occlusion, the myocardium in the heart wall is suddenly

choked off from oxygen, glucose, and other nutrients previously delivered by

the coronary artery. The stricken person may experience crushing chest pain

or angina (an-JEYE-nuh) pectoris (PEK-tor-is). A coronary bypass operation

may be performed. In this operation, the surgeon bypasses the occluded parts

of the coronary arteries by implanting small sections of veins obtained from

other areas of the body. Hopefully, the operation works, and fresh blood is

shunted past and around the blocked vessel areas to successfully feed the

nutrient-starved cardiac muscle.

Quiz

Refer to the text in this chapter if necessary. A good score is at least 8 correct

answers out of these 10 questions. The answers are listed in the back of this

book.

1. The circulatory system is literally named for its characteristic of:

(a) Transporting nutrients to the body tissues

(b) Carrying waste products from the body tissues

(c) Traveling through the body in a straight line

(d) Tracing a circle in its journey to and from the heart

2. The smallest branches of the arteries:

(a) Capillaries

(b) Veins

(c) Venules

(d) Arterioles

3. The _____ are the ‘‘entrance rooms’’ at the top of the heart:

(a) Atria

(b) Auricles

(c) Ventricles

(d) Myocardia

4. The left-heart circulation is alternately called the _____ circulation:

(a) Pulmonary

(b) Systemic

(c) Cardiorespiratory

(d) Cerebrovascular

CHAPTER 16 Blood and Circulatory System 297

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 297 1-388

5. The powerful cardiac muscle portion of the heart wall:

(a) Semilunar valves

(b) Endocardium

(c) Myocardium

(d) Pericardium

6. The primary pacemaker of the heart:

(a) Myocardium

(b) Left atrium

(c) Sinoatrial node

(d) Right A-V valve

7. Half-moon shaped flaps that control the entry of blood into the aortic

arch and common pulmonary artery:

(a) Atrioventricular valves

(b) Z-lines

(c) Semilunar valves

(d) Crescent muscles

8. The relaxation and filling phase of each heart chamber:

(a) Diastole

(b) Fibrillation

(c) Systole

(d) Bacterial endocarditis

9. Heart murmurs represent:

(a) Turbulent back-flow of blood through leaky valve flaps

(b) Smooth and efficient blood flow through healthy open valves

(c) Extensive arteriosclerosis

(d) A false appearance of atherosclerosis

10. The vessel most frequently used to take a person’s blood pressure:

(a) Superior vena cava

(b) Brachial vein

(c) Common pulmonary artery

(d) Brachial artery

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 298 1-388

PART 4 Anatomy and Physiology of Animals

298

The Giraffe ORDER TABLE for Chapter 16

(Key Text Facts About Biological Order Within An Organism)

1. ____________________________________________________________

2. ____________________________________________________________

3. ____________________________________________________________

4. ____________________________________________________________

5. ____________________________________________________________

The Dead Giraffe DISORDER TABLE for Chapter 16

(Key Text Facts About Biological Disorder Within An Organism)

1. ____________________________________________________________

2. ____________________________________________________________

3. ____________________________________________________________

4. ____________________________________________________________

5. ____________________________________________________________

The Spider Web ORDER TABLE for Chapter 16

(Key Text Facts About Biological Order Beyond the Individual Organism)

1. ____________________________________________________________

CHAPTER 16 Blood and Circulatory System 299

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 299 1-388

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 300 1-388

300

CHAPTER

17

Immune and

Lymphatic Systems:

‘‘The Best Survival

Offense Is A Good

Defense!’’

Chapter 16 featured the blood circulatory (cardiovascular) system and briefly

mentioned the role of certain plasma proteins in helping to protect the body

from foreign invaders. The most appropriate term to describe this protection

is immunity (ih-MYEW-nih-tee) – ‘‘a condition of ’’ (-ity) ‘‘not serving’’

(immun) disease. Thus, when a living organism has an immunity, or it is

immune (ih-MYEWN), then it does not serve or buckle-under to the

Copyright 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click Here for Terms of Use.

onslaught of a particular foreign invader or disease. Such immunity is accom-

plished by the operation of a strong body defense. (Recall from Chapter 6

that immune also means ‘‘safety.’’)

The Lymphatic System: A Shadow Circulation of

the Blood

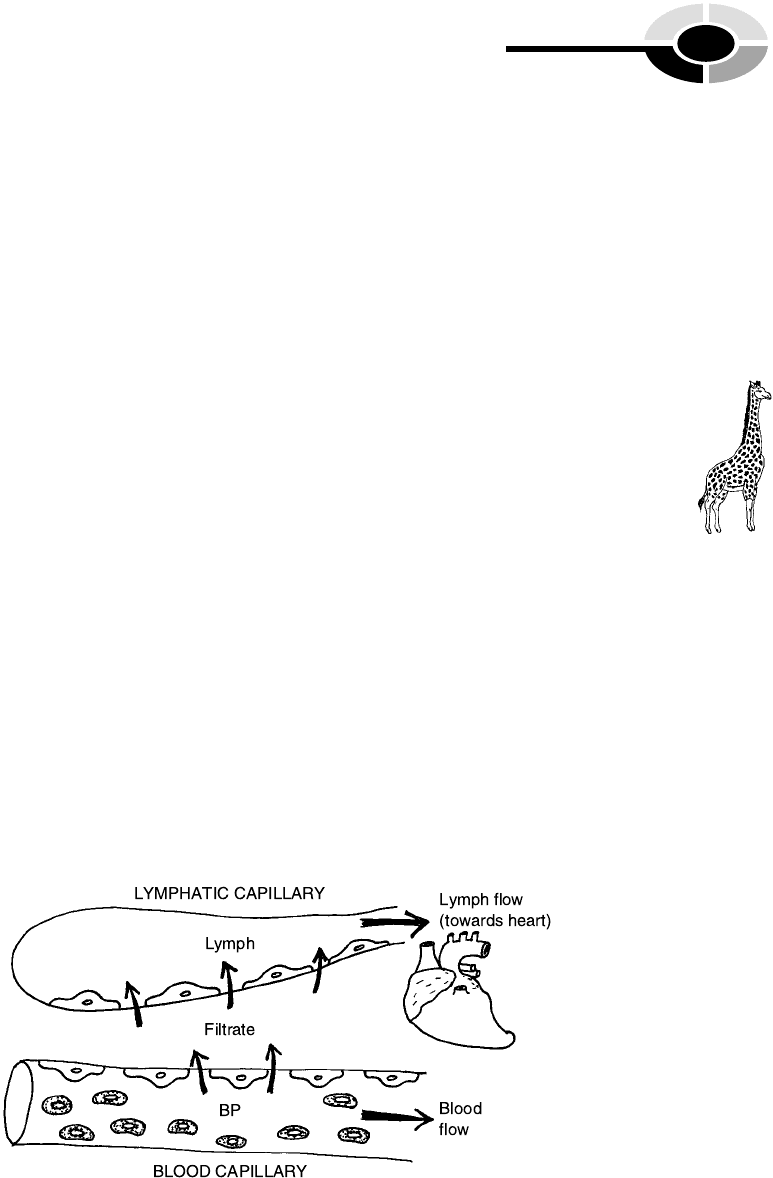

Closely associated with immunity is the lymphatic (lim-FAT-ik) system. The

lymphatic system consists of a collection of lymphatic organs and lymphatic

vessels running between them. In a practical sense, the lymphatic system can

be thought of as a shadow circulation of the blood circulation. The main

reason is that the lymphatic capillaries run side-by-side (like a shadow) along

the tiny blood capillaries (Figure 17.1).

The lymphatic capillaries are special in that they are dead-ended. Since

they are closed at the far end, their fluid contents, the lymph (LIMPF), flows

in one direction only – towards the heart. The word, lymph, literally means

‘‘clear spring water.’’ This meaning derives from the usually clear, watery

appearance of the lymph. The lymph is actually a filtrate (FILL-trait) –

filtration product – of the blood, the blood in the nearby capillaries. The

blood pressure pushes outward, thereby filtering water, NaCl, and various

foreign objects (such as dirt, bacteria, or cancer cells) out of the blood and

into the lymphatic capillaries. Since the lymph usually contains no erythro-

cytes, it looks clear, rather than red-colored. But eventually, the lymphatic

CHAPTER 17 Immune/Lymphatic Systems 301

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 301 1-388

Fig. 17.1 An overview of the lymphatic circulation. BP = blood pressure.

1, Order

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 302 1-388

vessels drain their cleansed lymph into several major blood veins that flow

into the top of the heart.

THE RETICULOENDOTHELIAL SYSTEM

The lymphatic system is sometimes given the alternate name of reticuloen-

dothelial (reh-TIK-you-loh-en-do-THEE-lee-al) system. The reticuloendothe-

lial or R-E system is a ‘‘little network’’ (reticul) of lymphatic vessels that are

lined by endothelial (en-doh-THEE-lee-al) cells. Endothelial cells are flat,

scale-like cells that line both blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. And

because these endothelial cells are so flat, lymph (and its contained dirt,

bacteria, or cancer cells) are readily filtered through or between them.

Since the lymphatic (reticuloendothelial) system receives dirt, bacteria,

debris, viruses, and cancer cells that have been filtered out of the blood-

stream, it serves a critical role in immunity (body defense) by cleaning up

the blood, and then returning the cleansed fluid back to the blood.

Remember this general saying: ‘‘From the blood the lymph is formed, and

back to the blood the lymph doth return.’’ The first lymph filtered from the

bloodstream is dirty (in the sense that it often carries contaminants or foreign

invaders), while the final lymph is clean (in the sense that the contaminants

and foreign invaders have been removed). Therefore, in the process of filter-

ing and cleaning the material that is leaked out of the blood capillaries, the

lymphatic (reticuloendothelial) system provides immunity.

We can summarize the important inter-relationships by this equation:

LYMPHATIC SYSTEM ¼ RETICULOENDOTHELIAL ðR-EÞ

SYSTEM ¼ IMMUNE SYSTEM

Antibodies and Macrophages Attack the

Antigens

Most cells carry chemical markers upon their surface membranes that

uniquely identify them. Thus, cells in a particular human body have their

own chemical surface markers that mark them as ‘‘self.’’ Such cells are not

attacked by the body’s immune system. Foreign cells transplanted from some

other human body, or from a bacterium or cancer cell, however, have dif-

PART 4 Anatomy and Physiology of Animals

302

3, Order

2, Order

ferent surface markers that mark them as ‘‘non-self.’’ The general name for

such surface markers is antigens (AN-tih-jens).

The word, antigen, means ‘‘produced’’ (-gen) ‘‘against’’ (anti-). This mean-

ing reflects the fact that antigens are ‘‘non-self ’’ marker proteins that label

particular cells as foreign. Therefore, the antigens are foreign proteins that

cause antibodies (AN-tih-bah-dees) to be ‘‘produced against’’ them.

Antibodies, in turn, are proteins produced by the body’s immune system

that attack and destroy foreign antigens. The overall process is called an

antigen–antibody reaction.

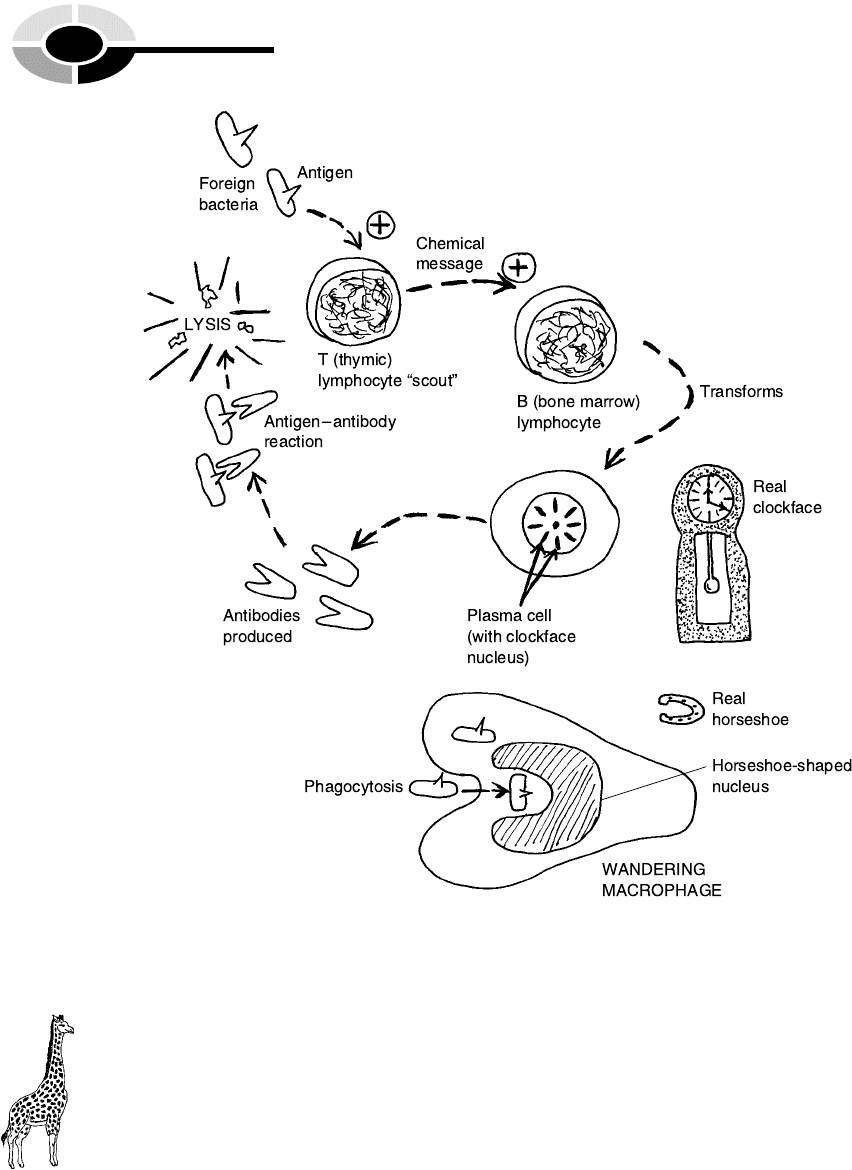

The antigen–antibody reaction comes about after a series of preceding

steps (Figure 17.2). The first step is identification of a foreign cell and its

surface antigen by a thymic (THIGH-mik) lymphocyte (LIMPF-oh-sight)

within the body tissues. The thymic lymphocyte is also abbreviated as T-

lymphocyte (or as a T-cell, mentioned back in Chapter 6). The T-lymphocytes

prowl around within the extensive network of the reticuloendothelial system

and act much like scouts. They send out a chemical signal whenever a foreign

antigen is encountered.

The bone marrow or B-lymphocytes receive the chemical messages from the

T-lymphocyte scouts. The B-lymphocytes then undergo a marked differentia-

tion (process of becoming specialized or different). They transform into

plasma cells. Plasma cells have a prominent ‘‘clock face’’ nucleus when

viewed through a compound light microscope. There is dark chromatin

(kroh-MAT-in) visible – strands of DNA that have not yet coiled together

to create chromosomes. These chromatin fragments are arranged in a circular

fashion around the edges of the nucleus, giving it a distinct ‘‘clock face’’

appearance.

It is the plasma cells that actually produce the antibodies. Once produced,

the individual antibody molecules attach to the foreign antigens, like two

pieces of a jigsaw puzzle fitted together. The result we have called an anti-

gen–antibody reaction. When the antibody combines, it causes a lysis (break-

down) of the invading cell carrying the foreign antigen. Thus, millions of

invading or abnormal cells (and their antigens) are efficiently ruptured and

scattered into tiny pieces.

Moving nearby is a defensive army of wandering macrophages (MAH-

kroh-fah-jes), or ‘‘large’’ (macr) ‘‘eating’’ (phag) cells. Such wandering

macrophages often include the monocytes (MAHN-oh-sights). The mono-

cytes are a type of leukocyte that has a ‘‘single’’ (mono-), large, horseshoe-

shaped nucleus. The monocyte can creep out of the blood in capillaries by

making amoeboid (amoeba-like) movements through their extremely thin

walls. They enter the surrounding tissue and extend their cytoplasm like

twin arms or pseudopodia. The monocytes readily surround and engulf

CHAPTER 17 Immune/Lymphatic Systems 303

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 303 1-388

entire invading cells and their foreign antigens by means of phagocytosis

(cell eating).

Hence, by two major processes, antigen–antibody reactions and phagocy-

tosis, a state of immunity from disease is usually accomplished within the

human body.

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 304 1-388

PART 4 Anatomy and Physiology of Animals

304

Fig. 17.2 Antibodies and macrophages attack foreign antigens.

4, Order

The Major Lymphatic Organs

So far, we have mainly been focusing upon the lymphatic vessels and the

defensive reactions of the immune system. But, remember that the lymphatic

system consists of a collection of lymphatic organs, as well as lymphatic

vessels.

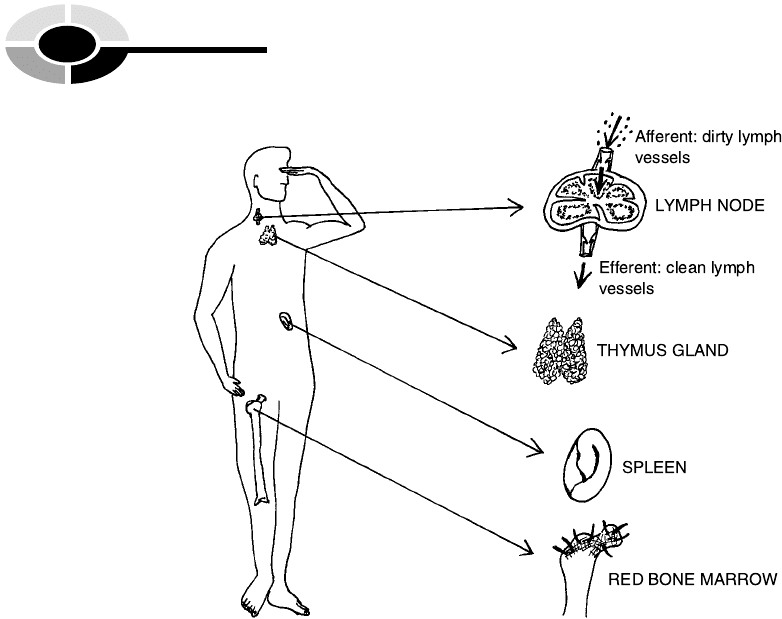

THE LYMPH NODES

The most widespread lymphatic organs are the lymph nodes (NOADS). The

lymph nodes are a group of small, bean-like organs scattered in clusters in

various parts of the body (Figure 17.3). Afferent (AF-fer-ent) lymphatic ves-

sels ‘‘carry’’ (fer) dirty lymph ‘‘towards’’ (af-) the lymph nodes. Efferent

(EE-fer-ent) lymphatic vessels carry clean lymph ‘‘away from’’ (ef-) them.

THE THYMUS GLAND

A most unusual lymphatic organ is the thymus (THIGH-mus) gland. The

word, thymus, comes from the Ancient Greek for ‘‘warty outgrowth,’’ reflect-

ing the bumpy appearance of this endocrine gland. The thymus is a thin, flat

gland lying just deep to the sternum (STER-num) or ‘‘breastplate.’’ This

gland consists of two bumpy-looking lobes. The thymus gland secretes the

hormone, thymosin (thigh-MOH-sin), which stimulates the activity of the

lymphocytes and other parts of the body’s immune system. It also produces

thymic (THIGH-mik) lymphocytes (introduced as T-cells or T-lymphocytes,

earlier).

The thymus gland is most prominent in young humans and other mam-

mals. (In lambs, it is called the ‘‘throat sweetbread,’’ because it is often eaten

as sweet-tasting meat.) It reaches its maximum size at puberty, then progres-

sively decreases in size. In most adults, the thymus is completely gone, having

been replaced by fatty connective tissue. The thymus is thought to play an

important role in the development of immune competence in youngsters – a

growing ability to ward off various diseases. The disappearance of the thy-

mus in adults may be related to the gradual decline of immune competence

seen in older persons, thereby making them more susceptible to cancer and

pneumonia.

CHAPTER 17 Immune/Lymphatic Systems 305

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 305 1-388

RED BONE MARROW

The red bone marrow found within spongy bone (Chapter 13) is a third

important type of lymphatic organ. Besides its role in hematopoiesis

(blood cell formation), the red bone marrow is a source of B-lymphocytes.

As you may recall, the B-lymphocytes differentiate into plasma cells when

they are chemically signaled by the T-lymphocytes that a foreign invader

(antigen) is present. And these plasma cells, in turn, produce antibodies.

SPLEEN

In humans, the spleen is a dark red organ attached to the left side of the

stomach. It looks somewhat like a thick, crescent-shaped-roll (croissant), and

it rather feels like one, being soft and spongy to the touch. Besides hemato-

poiesis, the spleen (like the red bone marrow) is involved in the recycling and

destruction of old, beaten-up erythrocytes. It also stores blood and contains a

lot of lymphatic tissue. The spleen is rich in lymphocytes, plasma cells, and

[13:26 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 306 1-388

PART 4 Anatomy and Physiology of Animals

306

Fig. 17.3 Some major lymphatic organs in humans.