Layman D. Biology Demystified: A Self-Teaching Guide

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 6 Bacteria and Homeless Viruses 107

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 107 1-388

1, Disorder

1, Order

Viruses: Non-living Parasites of Cells

In this chapter, we have introduced and briefly discussed the Five-Kingdom

System commonly used to classify all living organisms. Note that in the

preceding sentence, the word, living, was emphasized. The reason for this

emphasis is the puzzling existence of a real organic oddball, the viruses.

The term virus comes from the Latin and exactly means ‘‘a poison.’’ This

name probably derives from the fact that a virus is a non-living superchemi-

cal that always invades living cells and, in a sense, ‘‘poisons’’ them by becom-

ing a parasite. A virus, you see, cannot reproduce on its own. Therefore, it

parasitizes human, animal, plant, or bacterial cells and uses their DNA/RNA

to reproduce itself. In the process, the invaded cell is often destroyed, and the

living organism becomes ill or dies.

VIRAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

A quick glance at Figure 6.4 (A) will quickly reveal why viruses are not

considered living cells – they contain no plasma membrane or other orga-

nelles! A virus basically is a tiny parasitic particle whose simple structure

consists of a core of nucleic acid surrounded by a coat of proteins. This

extremely simple structure is enough, because viruses do not eat or drink,

grow, synthesize proteins, or reproduce by themselves. Each viral particle

contains either DNA or RNA as its nucleic acid, but not both of them.

Recall that both DNA and several types of RNA are required for protein

synthesis. Hence, viruses cannot make their own proteins.

Helical (HEE-lih-kal) viruses contain nucleic acid wound up tightly into a

coil or spiral, surrounded by a coat of small repeating proteins. Polyhedral

(PAHL-ee-he-dral) viruses have a protein coat with ‘‘many’’ (poly-) triangular

faces coming together. Enveloped viruses are enclosed by an outer lipid envel-

ope. The strangest of the lot may be the bacteriophage (back-tee-ree-oh-

FAYJ), which is sometimes just called a phage (FAYJ). Bacteriophage lit-

erally means ‘‘bacteria-eater’’! While the bacteriophage doesn’t exactly eat

bacteria, it does attack and destroy many types of bacterial cells. The bacter-

iophage (phage) particle is topped by a multiple-faced head portion, a slender

neck within a protein sheath, and several long tail fibers flairing out at the

bottom. These tail fibers attach to the cell wall of the attacked bacterium,

then inject viral DNA into it. (Examine Figure 6.4, B.) The injected viral

DNA uses the bacterial host cell DNA and RNA to reproduce itself in huge

numbers. Eventually, there may be so many new virus particles that they

release enough powerful enzymes to cause the complete lysis (rupture and

breakdown) of the infected bacterium.

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 108 1-388

PART 3 Five Kingdoms of Life, plus Viruses

108

Fig. 6.4 Virus structure and action. (A) Four major types of virus structure.

(B) Bacteriophage attacking a bacterium.

THE WORLDWIDE AIDS EPIDEMIC

Dangerous viral attacks upon human cells, not just bacterial cells, are unfor-

tunately quite common. A prominent case in point is the deadly AIDS virus.

AIDS is an abbreviation for Acquired Immunodeficiency (im-yew-no-deh-

FISH-en-see) Syndrome. This disease is caused by infection of human cells

with the human immunodeficiency virus,orHIV. The HIV particles are

usually transmitted from an infected person to someone else during unpro-

tected sexual intercourse. However, the virus may also be spread when the

tears or saliva of an infected person go into another person’s blood, or from

blood-to-blood during a transfusion.

The HIV particles are enveloped viruses that attack the T-cells in a

human’s immune (im-YOON) or ‘‘safety’’-providing system. The viruses

fuse with the T-cell’s plasma membrane, then release their viral RNA into

the cell. Eventually, the host T-cell produces DNA, which then directs the cell

organelles to create new HIV particles. The new viruses bud-off from the

surface of the host cell, and eventually infect many others.

Infection with HIV particles disturbs the immune or self-protective func-

tions of the T-cell. When thousands of T-cells become infected, then, the

immunodeficiency syndrome shows up. The AIDS virus, itself, does not

kill the victim. Rather, it is the prolonged immunodeficiency of the infected

person that is deadly. With very little immunity (protection) from disease in

general, the AIDS patient becomes an easy victim for infection by many

dangerous bacteria, such as those causing pneumonia.

Quiz

Refer to the text in this chapter if necessary. A good score is at least 8 correct

answers out of these 10 questions. The answers are found in the back of this

book.

1. Taxonomy essentially involves:

(a) Study of surgical techniques for operating upon animals

(b) Searching for general rules or laws for classifying organisms

(c) Removing harmful species from particular ecosystems

(d) Teaching people about the dangers or benefits of particular health

practices

CHAPTER 6 Bacteria and Homeless Viruses 109

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 109 1-388

4, B-Web

2. Often considered the very first (most ancient) and simplest of all groups

of organisms:

(a) Protists

(b) Fungi

(c) Plantae

(d) Animalia

3. Kingdom _____ is the one including bacteria:

(a) Amoebae

(b) Protista

(c) Monera

(d) Wartae

4. Technical term for the ‘‘Family of Man’’:

(a) Primates

(b) Mammalia

(c) Hominids

(d) Vertebrates

5. Homo sapiens, apes, monkeys, and lemurs all belong to the _____

Order:

(a) Primate

(b) Hominid

(c) Homo

(d) Mammalia

6. You scoop up a lump of wet muck and examine it through a

microscope. Tiny amoebas slowly moving through the muck can be

classified into what Kingdom?

(a) Monera

(b) Protista

(c) Animalia

(d) Fungi

7. The Phylum Chordata:

(a) Includes all organisms with a slender cord or vertebral column in

their backs

(b) Does not involve any mammals

(c) Chiefly encompasses the world of plants

(d) Focuses upon the fungi

8. Berry-shaped bacteria arranged together like a bunch of grapes:

(a) Streptococci

(b) Diplococci

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 110 1-388

PART 3 Five Kingdoms of Life, plus Viruses

110

(c) Bacilli

(d) Staphylococci

9. It is not wise to handle raw chicken, then lick your fingers, because:

(a) Chicken skin is a deadly poisonous material

(b) Septicemia is nearly inevitable

(c) Too many foreign organic compounds may be ingested

(d) Salmonella bacteria on the chicken may release endotoxins

10. The basic structure of a virus:

(a) Nucleus surrounded by a cell membrane and organelles

(b) Core of nucleic acid surrounded by a protein coat

(c) Just an envelope of DNA, nothing else

(d) Fast-moving cell with hair-like projections

The Giraffe ORDER TABLE for Chapter 6

(Key Text Facts About Biological Order Within An Organism)

1. ____________________________________________________________

The Dead Giraffe DISORDER TABLE for Chapter 6

(Key Text Facts About Biological Disorder Within An Organism)

1. ____________________________________________________________

CHAPTER 6 Bacteria and Homeless Viruses 111

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 111 1-388

The Spider Web ORDER TABLE for Chapter 6

(Key Text Facts About Biological Order Beyond The Individual

Organism)

1. ____________________________________________________________

2. ____________________________________________________________

3. ____________________________________________________________

4. ____________________________________________________________

5. ____________________________________________________________

The Broken Spider Web DISORDER TABLE for Chapter 6

(Key Text Facts About Biological Disorder Beyond The Individual

Organism)

1. ____________________________________________________________

2. ____________________________________________________________

3. ____________________________________________________________

4. ____________________________________________________________

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 112 1-388

PART 3 Five Kingdoms of Life, plus Viruses

112

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 113 1-388

CHAPTER

7

The Protists:

‘‘First of All’’

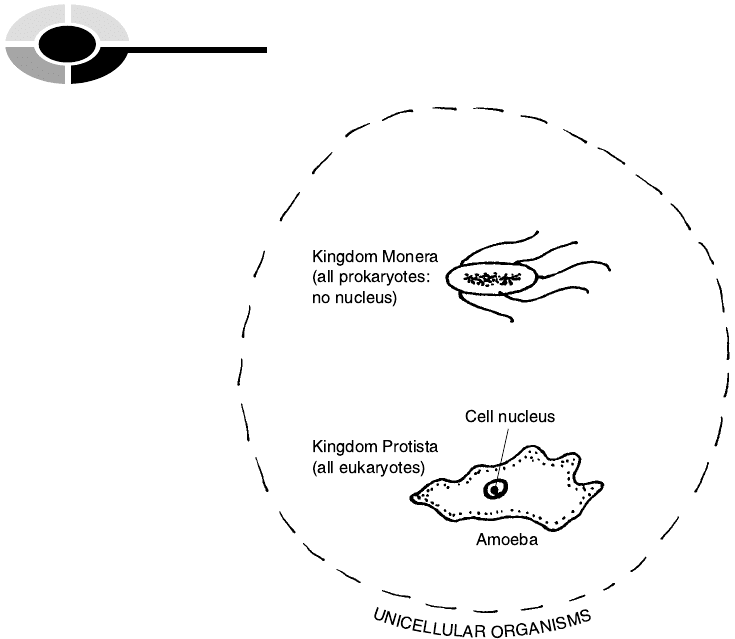

Now that bacteria (Kingdom Monera) and viruses (no kingdom) have been

discussed, it is time to take a closer look at the protists. Figure 7.1 reviews the

fact that unicellular organisms belong to one of either two major kingdoms –

Kingdom Protista or Kingdom Monera.

Protists ¼ All Single-celled Eukaryotes

The protists include all of the single-celled organisms having a nucleus. This

is a huge category, of course! And this category is distinguished from the

bacteria, you may remember, which are the main single-celled organisms not

having a nucleus. Recollect that Chapter 6 used the primitive amoeba as a

representative member of the Kingdom Protista.

113

1, Web

2, Web

Copyright 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click Here for Terms of Use.

‘‘WHERE DID THE FIRST CELL ORGANELLES COME

FROM?’’

Somewhere along the vast timescale of evolutionary history, a group of

prokaryote cells without nuclei eventually developed into eukaryote cells

containing nuclei. Recall (Chapter 3) that the first eukaryote cells appeared

about 2.1 billion years ago. These original eukaryote cells started what we

loosely call the protists, literally the ‘‘very first’’ organisms with nucleus-

containing cells. Speculation about just how these nucleated protists first

appeared has lead to the Theory of Endosymbiosis (EN-doh-sim-be-OH-sis).

The concept of symbiosis (sim-be-OH-sis), in general, involves a ‘‘condition

of ’’ (-osis) ‘‘living’’ (bi) ‘‘together’’ (sym-). The term endosymbiosis, then,

means a condition of living together and ‘‘within’’ (endo-). In a condition

of endosymbiosis, two organisms of different species live together, with the

smaller organism living inside the cells of the larger organism, which act as

hosts. [Study suggestion: Picture a band of gypsies living together in a group

of tents surrounded by a fence. The gypsies used to live independently, but

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 114 1-388

Fig. 7.1 The two kingdoms of unicellular organisms.

PART 3 Five Kingdoms of Life, plus Viruses

114

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 115 1-388

for their safety and well-being, their band has come to live together with

other members of a circus. The circus compound itself, including the

fenced-off gypsy area, is surrounded by a tall wall. In return for food and

protection, the gypsies live inside the circus compound and entertain their

hosts (circus owners) and read their fortunes! The contained gypsy band and

the larger host circus compound therefore live in a condition of endosym-

biosis, where each group benefits.]

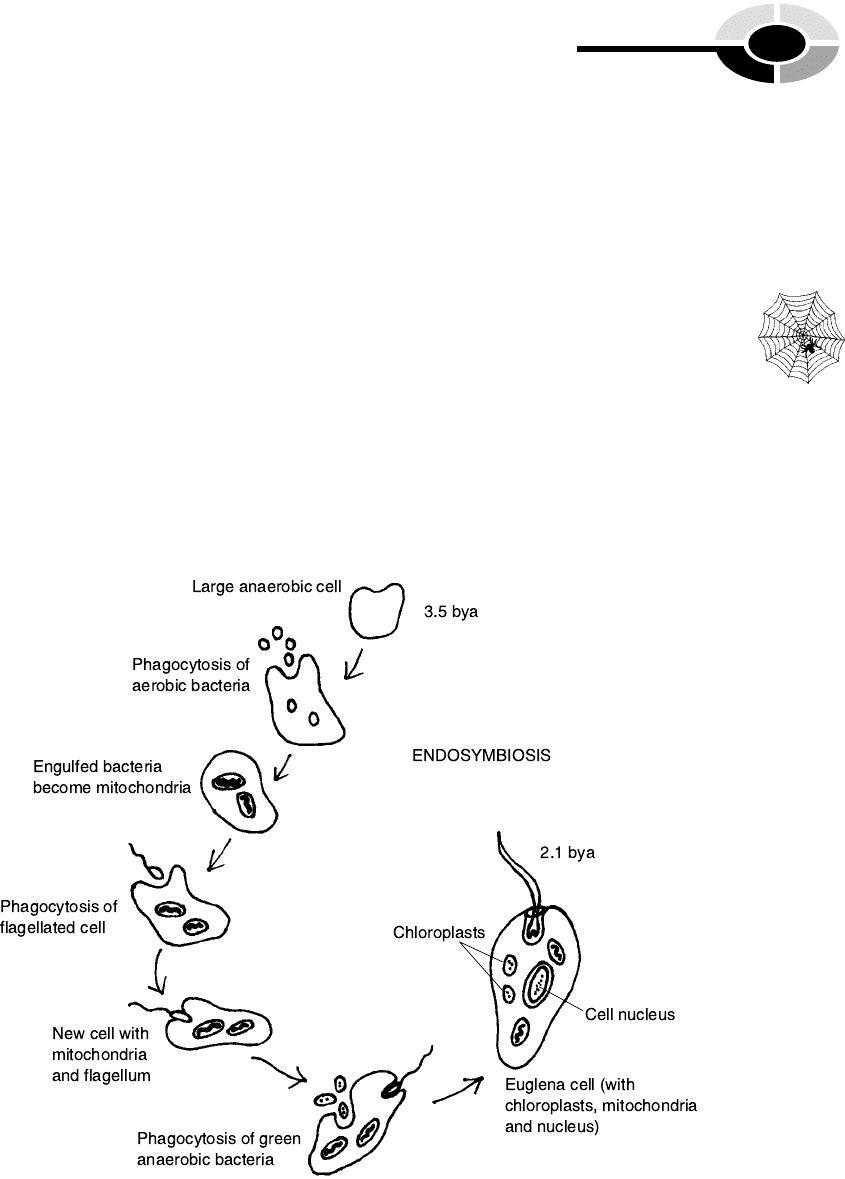

According to the Theory of Endosymbiosis, small prokaryote cells that

used to live independently, moved into larger host prokaryote cells and

achieved greater safety and well-being. (Examine Figure 7.2.) After living

together in a state of endosymbiosis for a long time, the smaller prokaryote

cells completely lost their ability to live independently. Instead, they evolved

into nuclei and other organelles. Consider the possible origins of the mito-

chondrion, flagellum, and chloroplast. Mitochondria may have evolved from

tiny, free-living, aerobic bacteria that were engulfed via phagocytosis by a

larger anaerobic cell. Eventually, the bacteria mutated into mitochondria and

CHAPTER 7 The Protists: ‘‘First of All’’ 115

3, Web

Fig. 7.2 Endosymbiosis and the origin of cell organelles.

became permanent residents and organelles of their larger host cell. By this

means, the once anaerobic host cell became an aerobic (O

2

-using) one con-

taining mitochondria. Suppose that the now-aerobic cell then phagocytosed

(fag-oh-SIGH-toesd) a small, fast-moving prokaryote with a whip-like fla-

gellum. The entire small flagellated cell eventually evolved into a new orga-

nelle for the larger host cell – a flagellum. The host cell benefited by gaining

increased mobility.

Similarly, the chloroplast and its capacity for photosynthesis may have

evolved by endosymbiosis. Recall (Chapter 3) that tiny, bluish-green, chlor-

ophyll-containing bacteria, shaped like threads or filaments, may have been

the most ancient of living things. These bacteria were prokaryotes, lacking a

nucleus. Many biologists speculate that early aerobic cells may have phago-

cytosed such bluish-green bacteria, which eventually evolved into slender

chloroplast organelles. The large host cells would benefit by obtaining the

capacity to produce energy via photosynthesis.

The ultimate result of all this endosymbiosis going on over long periods of

time may well be such modern protists as Euglena (yew-GLEN-ah). This

modern protist contains both mitochondria and chloroplasts as organelles,

and it moves about rapidly by means of its flagellum. Commonly found in

ponds, Euglena living in sunny water develop chloroplasts and become auto-

trophic, producing their own energy via photosynthesis. They use their fla-

gella to scoot towards the light. In dark pond water, however, Euglena

becomes an aerobic heterotroph, absorbing nutrients from the rich pond

water and using its mitochondria to produce energy aerobically. Such

dark-dwelling Euglena may even lose their chloroplasts!

So, is Euglena a plant (living anaerobically via photosynthesis), or is it an

animal (living aerobically and using oxygen)? The answer is, ‘‘Neither!’’ For

you see, Euglena is a protist!

DEBATE ABOUT THE KINGDOM

In recent years, there has been much debate among biologists about just

whether the protists make up a particular kingdom, or whether the group

should be split up into many separate kingdoms. The reason for this debate is

the great differences among the 60,000 or so known species that make up the

protist group. But there is one essential fact that all of the unicellular protists

have in common. Although each of them contains a nucleus, the single cell of

each protist is an entire organism! This makes the protists stand out distinctly

from the nucleated cells of multicellular organisms, like humans, most plants,

and animals. Human cells, for instance, typically have a nucleus, but they are

[13:24 13/6/03 N:/4058 LAYMAN.751/4058-Alltext.3d] Ref: 4058 Layman: Biology Demystified All-text Page: 116 1-388

PART 3 Five Kingdoms of Life, plus Viruses

116

1, Order